Abstract

Modafinil (MOD) exhibits therapeutic efficacy for treating sleep and psychiatric disorders; however, its mechanism is not completely understood. Compared with other psychostimulants inhibiting dopamine (DA) uptake, MOD weakly interacts with the dopamine transporter (DAT) and modestly elevates striatal dialysate DA, suggesting additional targets besides DAT. However, the ability of MOD to induce wakefulness is abolished with DAT knockout, conversely suggesting that DAT is necessary for MOD action. Another psychostimulant target, but one not established for MOD, is activation of phasic DA signaling. This communication mode during which burst firing of DA neurons generates rapid changes in extracellular DA, the so-called DA transients, is critically implicated in reward learning. Here, we investigate MOD effects on phasic DA signaling in the striatum of urethane-anesthetized rats with fast-scan cyclic voltammetry. We found that MOD (30–300 mg/kg i.p.) robustly increases the amplitude of electrically evoked phasic-like DA signals in a time- and dose-dependent fashion, with greater effects in dorsal versus ventral striata. MOD-induced enhancement of these electrically evoked amplitudes was mediated preferentially by increased DA release compared with decreased DA uptake. Principal component regression of nonelectrically evoked recordings revealed negligible changes in basal DA with high-dose MOD (300 mg/kg i.p.). Finally, in the presence of the D2 DA antagonist, raclopride, low-dose MOD (30 mg/kg i.p.) robustly elicited DA transients in dorsal and ventral striata. Taken together, these results suggest that activation of phasic DA signaling is an important mechanism underlying the clinical efficacy of MOD.

Introduction

Modafinil (MOD; Provigil) exhibits therapeutic efficacy for treating a variety of neuropathologies, including sleep-related disorders such as narcolepsy (Wise et al., 2007), obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (Pack et al., 2001), shift-work sleep disorder (Czeisler, et al., 2005), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Swanson et al., 2006), and drug addiction (Anderson et al., 2009, 2012; Shearer et al., 2009). Similar to other psychostimulants used therapeutically, such as amphetamine (Adderall) and methylphenidate (Ritalin), MOD enhances locomotor activity (Kuczenski et al., 1991; Edgar and Seidel, 1997; Kuczenski and Segal, 2001), wakefulness (Wisor et al., 2001; Ishizuka et al., 2008), and cognitive ability (Barch and Carter, 2005; Kumar, 2008; Repantis et al., 2010). Indeed, a recent meta-analysis study has concluded that MOD can be safely used as a cognitive enhancer in healthy subjects (Battleday and Brem, 2015). Moreover, unlike other therapeutic psychostimulants, MOD exhibits limited potential for abuse (Deroche-Gamonet et al., 2002). These attractive psychostimulant characteristics have thus generated considerable interest in establishing the neuropharmacologic mechanism of MOD action.

Although MOD has been found to alter various neurotransmitter systems in the brain, including those for histamine, hypocretin (orexin), GABA, glutamate, norepinephrine, and serotonin, its effects on midbrain dopamine (DA) systems have received the greatest attention (Tanganelli et al., 1992; Ferraro et al., 1997; Chemelli et al., 1999; de Saint Hilaire et al., 2001; Ishizuka et al., 2003). Compared with transporters for other monoamines such as norepinephrine and serotonin, this atypical psychostimulant preferentially interacts with the dopamine transporter (DAT) and shows little affinity for receptors of monoamines and other neurotransmitters (Mignot et al., 1994; Madras et al., 2006; Zolkowska et al., 2009). However, whether MOD acts directly through DAT remains highly controversial. On the one hand, MOD exhibits weak affinity for DAT (Mignot et al., 1994; Madras et al., 2006; Zolkowska et al., 2009) and elicits only relatively modest increases in striatal dialysate DA (Ferraro et al., 1997; Loland et al., 2012). On the other hand, MOD’s effects appear to rely on DAT since MOD-induced wakefulness is abolished in DAT knockout mice (Wisor et al., 2001).

Based on work investigating actions of other DAT-inhibiting psychostimulants, another potential target for MOD is phasic DA signaling. DA neurons signal in two distinct modes, with slow, irregular firing of DA neurons generating a basal level of extracellular DA called tone during tonic DA signaling and burst firing of DA neurons generating rapid increases in extracellular DA (called transients) during phasic DA signaling (Floresco et al., 2003). Substantive evidence implicates a critical role played by phasic DA signaling in reward learning (Schultz et al., 1997; Day et al., 2007) and seeking (Phillips et al., 2003), and alterations in phasic DA signaling are hypothesized to contribute to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Tripp and Wickens, 2008) and drug abuse (Covey et al., 2014). DAT-inhibiting psychostimulants have also been shown to activate phasic DA signaling by increasing burst firing of DA neurons (Shi et al., 2000, 2004; Koulchitsky et al., 2012) and the frequency of DA transients in the striatum (Venton and Wightman, 2007; Covey et al., 2013; Daberkow et al., 2013), and by presynaptically enhancing DA release, in addition to inhibiting DA uptake (Wu et al., 2001a; Venton et al., 2006; Chadchankar et al., 2012). Whether MOD acts similarly to activate phasic DA signaling has not been examined.

Here, we use fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) at a carbon-fiber microelectrode (CFM) to investigate the effects of MOD on phasic DA signaling in urethane-anesthetized rats. The effects of MOD were examined in dorsal and ventral striata across a wide behaviorally relevant range of doses (30–300 mg/kg i.p.), based on effects on cognitive function, locomotion, and wakefulness (Edgar and Seidel, 1997; Béracochéa et al., 2001; Ward et al., 2004). Two measures of phasic DA signaling were assessed: the amplitude of electrically evoked phasic-like DA signals (Avelar et al., 2013) and the frequency of DA transients elicited in the presence of the D2 DA antagonist, raclopride (Venton and Wightman, 2007). DA transients were determined from nonelectrically evoked DA traces processed by principal component regression (PCR) (Keithley et al., 2009). In addition, the effects of MOD on the presynaptic mechanisms of DA release and uptake (Wu et al., 2001b) and on basal DA levels processed by PCR were examined. Taken together, our results suggest that activation of phasic DA signaling is a novel mechanism contributing to the therapeutic efficacy of MOD.

Methods

Animals.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (300–400 g) were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) and housed in a temperature-controlled vivarium on a diurnal light cycle (12-hour light/dark) with food and water provided ad libitum. Animal care conformed to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee at Illinois State University.

Surgery.

Rats were anesthetized with urethane (1.6 g/kg i.p.) and immobilized in a stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). Holes for reference, stimulating, and two CFMs were drilled. All coordinates—anteroposterior (AP), mediolateral (ML), and dorsoventral (DV)—are given in millimeters and are referenced to bregma (Paxinos and Watson, 1986). The stimulating electrode targeted the medial forebrain bundle (−4.6 AP, +1.3 ML, −7.5 DV). CFMs targeted ipsilateral dorsal (+1.2 AP, +3.0 ML, −4.5 DV) and ventral (+1.2 AP, +1.5 ML, −6.5 DV) striata. The Ag/AgCl reference electrode was placed in the contralateral cortex. Final coordinates for CFMs and stimulating electrodes were based on optimizing the electrically evoked DA signal and were not changed for the duration of the experiment.

Experimental Design.

DA was recorded in sequential 5-minute epochs, and for most recordings FSCV was performed simultaneously at separate CFMs implanted in dorsal and ventral striata of a single animal. In the first experimental design, four predrug and 30 postdrug epochs were collected, and electrical stimulation of the medial forebrain bundle was applied 5 seconds into each epoch. The effects of (2-hydroxypropyl)-β-cyclodextrin (vehicle) or MOD (30, 60, 100, or 300 mg/kg) were examined on electrically evoked phasic-like DA signals for the entire duration of DA measurements (15 minutes predrug and 160 minutes postdrug). The effects of vehicle or MOD across the same dose range as previously described on DA release and uptake were examined predrug and at 30 and 60 minutes postdrug. The effects of vehicle or high-dose MOD (300 mg/kg) on changes in basal DA were examined predrug and for 40 minutes postdrug. In the second experimental design, electrical stimulation was applied predrug and every 30 minutes postdrug to assess the veracity of the CFM. After predrug recordings, raclopride (2 mg/kg) was coadministered with low-dose MOD (30 mg/kg), and DA transients were analyzed during 5-minute epochs predrug and postdrug at 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes. All vehicles and drugs were administered i.p. in a total volume of 2 ml; n = 4–7 each in the dorsal and ventral striatum.

Electrochemistry.

DA measurements were recorded with FSCV by applying a triangular waveform (−0.4 to +1.3 V and back) to the CFM at a rate of 400 V/s every 100 ms. CFMs were fabricated by aspirating a single carbon fiber (r =3.55 µm; HexTow AS4, HexCel Corp., Stamford, CT) into a borosilicate capillary tube (1.2 mm o.d.; Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA) and pulling to a taper using a micropipette puller (Narishige, Tokyo). The carbon fiber was then cut to ∼100 µm distal to the glass seal. FSCV was performed by a universal electrochemistry instrument (Department of Chemistry Electronic Shop, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC) and commercially available software (ESA Bioscience, Chelmsford, MA). Current recorded at peak oxidative potential for DA (∼+0.6 V) was converted to DA concentration based on postcalibration of the CFM using flow-injection analysis in a modified Tris buffer (Kume-Kick and Rice, 1998; Wu et al., 2001b). DA was identified by the background-subtracted voltammogram (Michael et al., 1998; Heien et al., 2004). In experiments assessing effects of MOD on basal DA and DA transients, DA was additionally identified using PCR (as described subsequently).

Electrical Stimulation.

Electrical stimulation was computer generated and passed through an optical isolator and constant-current generator (Neurolog NL800; Digitimer Limited, Letchworth Garden City, United Kingdom). Biphasic stimulation pulses were applied to a twisted bipolar electrode (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA), with tips separated ∼1 mm. Stimulus parameters were an intensity of ±300 μA and a duration of the biphasic pulse of 4 ms (2 ms for each phase), with trains applied at a frequency of 60 Hz for 0.4 seconds (i.e., a total of 24 pulses).

Analysis of DA Release and Uptake.

Electrically evoked phasic-like DA signals were analyzed to determine maximal amplitude (i.e., maximal concentration of dopamine evoked by electrical stimulation [DA]max) and parameters for presynaptic DA release and uptake according to (Wightman et al., 1988; Wu et al., 2001b):

| (1) |

where [DA]p is the concentration of DA release per stimulus pulse, which is used to index DA release; k is the first-order rate constant for DA uptake; and f is the frequency of electrical stimulation. Here, [DA]p and k were determined by fitting electrically evoked DA signals to eq. 1 using nonlinear regression with a simplex-minimization algorithm (Wu et al., 2001b). Temporal distortion in measured DA responses was accounted for using a diffusion gap model, with the gap width held constant for each CFM across pre- and postdrug measurements (Wu et al., 2001b).

Analysis of Basal DA and DA Transients.

Changes in DA during nonelectrically evoked recording were assessed using PCR to resolve DA, pH, and background drift from raw FSCV recordings (Hermans et al., 2008; Keithley et al., 2009). In select files, PCR additionally resolved a repetitive background noise component. PCR analysis was accepted if any current in the recordings not accounted for by the retained principal components of the training sets, or residual (Q), was less than the 95% confidence threshold (Qα). Epochs where Q exceeded Qα were not used for analysis. Changes in basal (i.e., nonelectrically evoked) DA (Δ[DA]) per 5-minute epoch were determined by averaging all data points poststimulation of PCR-resolved traces. Here, Δ[DA] is independently presented for each 5-minute epoch, not as a contiguous concatenation in order to avoid resetting Q with a new background subtraction at the start of each epoch. DA transients were identified in PCR-resolved traces as peaks greater than 5× the root-mean-square noise using peak-finding software (MINI ANALYSIS; Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA).

Statistical Analysis.

Where appropriate, data are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. Unless noted subsequently, statistical analyses were performed with SAS/STAT software version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Time courses for [DA]max, [DA]p, and k were analyzed using a three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures with time, drug dose, and striatal region as factors. Path analysis (Mitchell 2001) was conducted to assess the dose-dependent direct effects of MOD on [DA]p and k, and the indirect effects of MOD on [DA]max via [DA]p and k. Alternative, reduced models were compared with the full model using Akaike information criteria (AIC) (Anderson, 2008). A two-way ANOVA with repeated measures assessed differences in DA-transient frequency with time and dose as factors. Correlations were performed with Sigma Plot 12.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA). Significance was set at P < 0.05.

Drugs.

Urethane, (2-hydroxypropyl)-β-cyclodextrin, and raclopride were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). MOD was provided by the Research Triangle Institute-National Institute on Drug Abuse (Raleigh, NC). Urethane and raclopride were dissolved in 150 mM NaCl prior to injection. MOD was dissolved in a mixture of 50% (2-hydroxypropyl)-β-cyclodextrin and nanopure w/v.

Results

MOD Robustly Increases the Amplitude of Electrically Evoked Phasic-Like DA Signals.

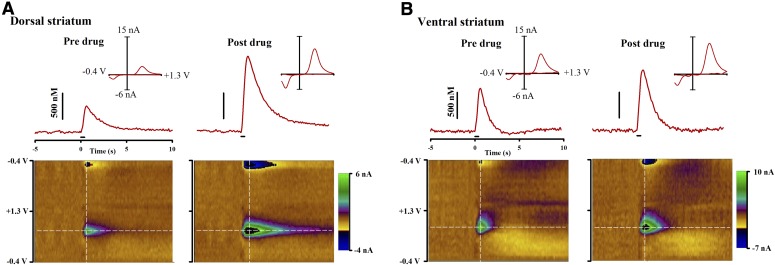

Figure 1 shows representative effects of MOD on electrically evoked phasic-like DA signals collected in dorsal (Fig. 1A) and ventral (Fig. 1B) striata. Recordings in the top of each panel show electrical stimulation of the medial forebrain bundle increasing DA as measured by FSCV at a CFM. Pseudo-color plots below, which serially display all voltammograms collected during the recording, and individual voltammograms (Fig. 1, inset) identify DA as the primary analyte recorded. MOD (100 mg/kg) increased [DA]max in both dorsal and ventral striata 60 minutes postdrug administration.

Fig. 1.

MOD (100 mg/kg i.p.) effects on electrically evoked phasic-like DA signals in dorsal (A) and ventral (B) striata measured by FSCV. (Top) Evoked DA signals elicited by electrical stimulation (demarcated by black line at time 0 seconds) predrug (left) and 60 minutes post-MOD (right). (Inset) Individual background-subtracted cyclic voltammogram taken from the peak signal (white vertical line) identifies the analyte as DA. (Bottom) Pseudo-color plot serially displaying all background-subtracted cyclic voltammograms (x-axis: time; y-axis: applied potential; z-axis: current). White horizontal line identifies the DA peak oxidative potential where the evoked DA trace was collected.

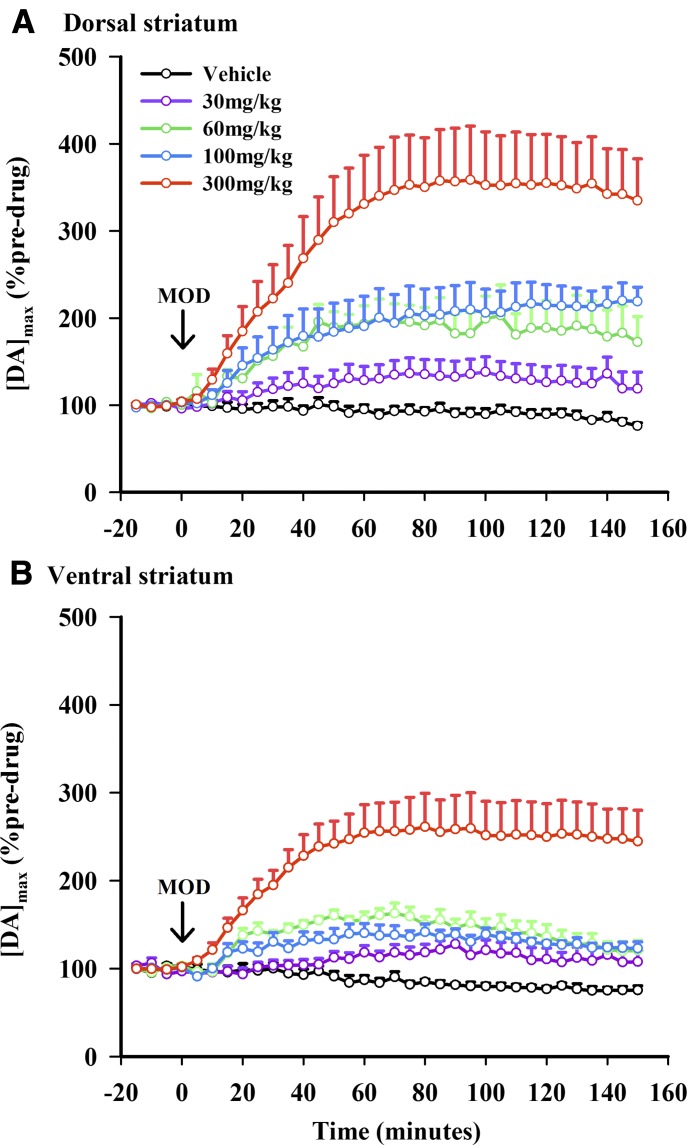

Figure 2 shows averaged time courses of MOD effects on [DA]max expressed as a percentage change from predrug in dorsal (Fig. 2A) and ventral (Fig. 2B) striata. All four doses of MOD (30, 60, 100, and 300 mg/kg) appeared to elevate [DA]max compared with vehicle control for more than 2.5 hours postdrug administration. Increases elicited by the highest MOD dose tested (300 mg/kg) were particularly robust at approximately 3-fold predrug levels. Consistent with representative recordings shown in Fig. 1, MOD appeared to elevate [DA]max to a greater extent in the dorsal than in the ventral striatum. A three-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant effects of time (F33, 1419 = 30.83, P < 0.0001), dose (F4, 43 = 15.47, P < 0.0001), and region (F1, 43 = 5.85, P = 0.0198). There were also significant time-by-dose (F132, 1419 = 9.04, P < 0.0001) and time-by-region (F132, 1419 = 4.17, P = 0.0207) interactions, but no time-by-dose-by-region (F132, 1419 = 0.68, P = 0.7031) and region-by-dose (F4, 43 = 0.70, P = 0.5970) interactions. Thus, MOD increased [DA]max in a time- and dose-dependent manner, with a greater relative effect in the dorsal striatum and different time courses in the two striatal regions and for drug doses.

Fig. 2.

MOD elicits time- and dose-dependent effects on the maximal concentration of the electrically evoked phasic-like DA signal ([DA]max) in dorsal (A) and ventral (B) striata. Data are expressed as a percentage of predrug and are the mean ± S.E.M. Arrow demarcates MOD administration at time 0 minutes. Data were analyzed for significance using three-way repeated measures ANOVA (n = 4–7).

MOD Increases DA Release and Decreases DA Uptake.

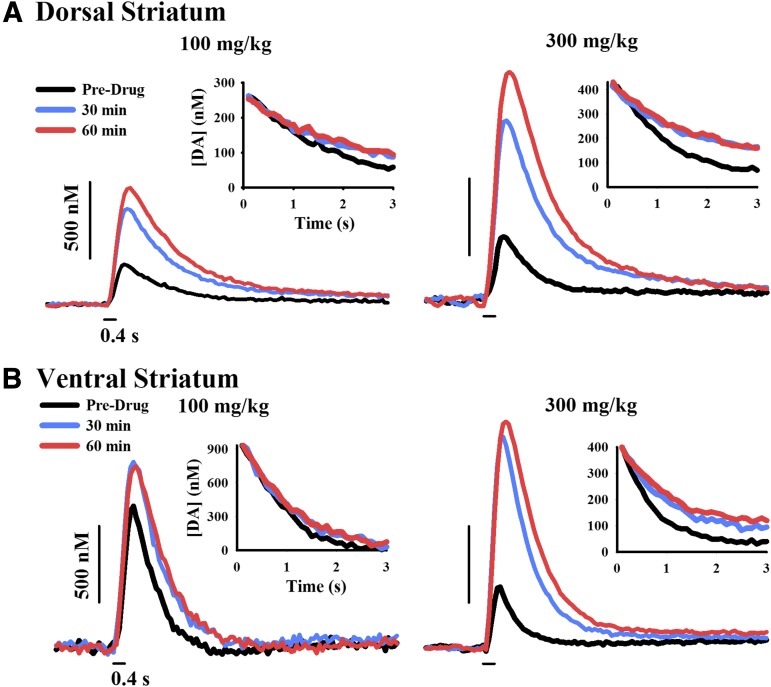

MOD-induced increases in [DA]max could be mediated by enhanced DA release and/or inhibited DA uptake. To initially assess whether MOD decreased DA uptake, electrically evoked decay curves were overlaid beginning at the same concentration (Fig. 3, inset), and the slopes were visually inspected between pre- and postdrug traces. The downward slope of the evoked trace is thought to reflect DA uptake and not DA release (Wu et al., 2001b). Thus, the flatter postdrug traces after MOD indicate slower DA extracellular clearance (Fig. 3). This qualitative approach suggests that MOD decreases DA uptake and that the increase in [DA]max may be due to DA uptake inhibition, at least in part. However, MOD-induced increases in DA release may also play a role, because the upward slope of the evoked trace reflects the balance of both DA release and uptake (Wu et al., 2001b).

Fig. 3.

Representative time- and dose-dependent effects of MOD on the extracellular clearance of electrically evoked DA in dorsal (A) and ventral (B) striata. FSCV traces of the electrically evoked DA signal (stimulus demarcated by short black lines) are shown for 100 mg/kg MOD (left) and 300 mg/kg MOD (right) at select time points. (Inset) Pre- and postdrug clearance curves are overlaid beginning at the same DA concentration and illustrate DA uptake inhibition.

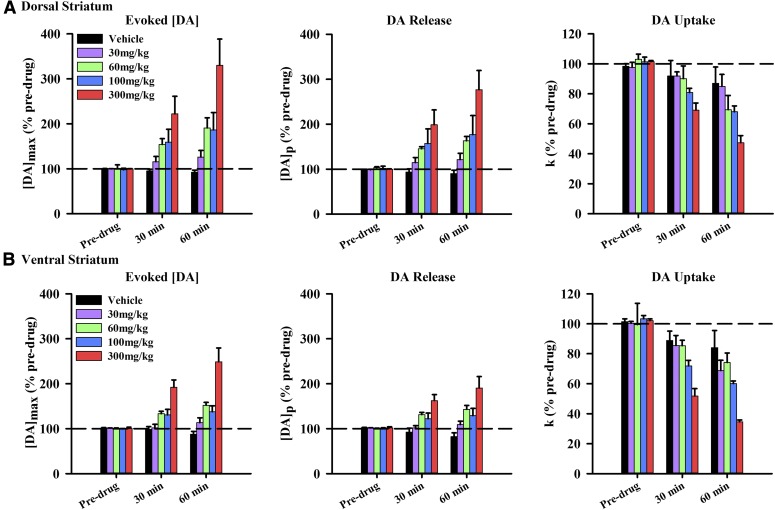

To quantitatively resolve MOD’s effect on DA release and uptake on [DA]max, electrically evoked responses were fit to eq. 1. Figure 4 compares the effects of MOD on [DA]max (left), DA release as indexed by [DA]p (middle), and DA uptake as indexed by k (right) for dorsal (Fig. 4A) and ventral (Fig. 4B) striata. Three time points were assessed: predrug and 30 and 60 minutes postdrug to canvass the initial MOD-induced increase in [DA]max. Three-way repeated measures ANOVA was used for statistical analysis of each parameter. Statistical analysis of [DA]max revealed significant effects of time (F2, 88 = 43.27, P < 0.0001) and dose (F4, 44 = 13.14, P = 0.0151), and significant time-by-dose (F8, 88 = 11.64, P < 0.0001) and time-by-region (F8, 88 = 3.59, P = 0.0316) interactions, but no significant time-by-dose-by-region (F8, 88 = 0.50, P = 0.8555) and region-by-dose (F4, 44 = 0.041, P = 0.7981) interactions. However, there was a trend for an effect of region (F1, 44 = 3.24, P = 0.0782). Compared with the complete time course for [DA]max in Fig. 2, which found a significant effect of region, the strong, but nonsignificant, trend for a region effect of MOD on [DA]max in Fig. 4 could be attributed to the reduced number of time points examined at maximal drug effect (>60 minutes). Analysis of [DA]p revealed significant effects of time (F2, 88 = 30.65, P < 0.0001), dose (F4, 44 = 9.96, P < 0.0001), and region (F1, 44 = 4.32, P = 0.0436) and significant time-by-dose (F8, 88 = 8.56, P < 0.0001) and time-by-region (F8, 88 = 4.32, P = 0.0162) interactions, but no significant time-by-dose-by-region (F8, 88 = 0.80, P = 0.6082) and region-by-dose (F4, 88 = 0.71, P = 0.5925) interactions. Finally, analysis of k revealed significant effects of time (F2, 88 = 132.04, P < 0.0001) and dose (F1, 44 = 12.50, P < 0.0001), as well as a significant time-by-dose interaction (F8, 88 = 8.95, P < 0.0001), but no significant time-by-dose-by-region (F8, 88 = 0.81, P = 0.5890), time-by-region (F2, 88 = 2.90, P = 0.0603), and region-by-dose (F4, 88 = 0.47, P = 0.7588) interactions. However, there was a trend for an effect of region (F1, 44 = 3.69, P = 0.0611). Taken together, these results demonstrate that MOD increases DA release and decreases DA uptake in a time- and dose-dependent fashion and preferentially increases DA release in the dorsal striatum; MOD may additionally inhibit DA uptake preferentially in the ventral striatum.

Fig. 4.

Effects of MOD on presynaptic DA release and uptake. Increases in the maximal concentration of the electrically evoked phasic-like DA signal ([DA]max) (left) are associated with an increase in DA release or [DA]p (middle) and a decrease in DA uptake or k (right) in dorsal (A) and ventral (B) striata. Data are expressed as a percentage of predrug and are the mean ± S.E.M. Data were analyzed for significance using three-way repeated measures ANOVA (n = 4–7).

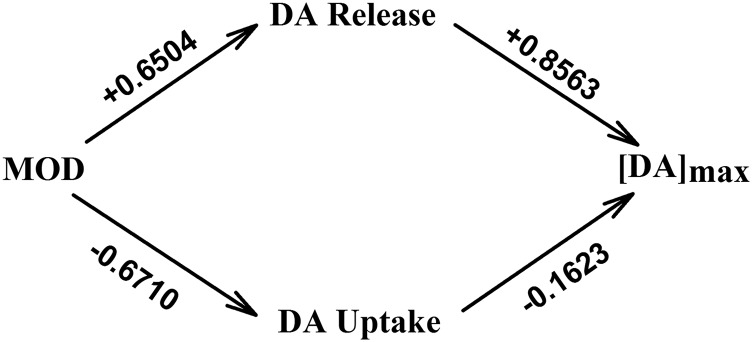

In theory, both an increase in DA release and a decrease in DA uptake could mediate an increase in [DA]max (Wu et al., 2001b). Therefore, we used path analysis to directly evaluate the respective contribution of these two presynaptic mechanisms to the dose-dependent effects of MOD on [DA]max. Path analysis (Mitchell, 1998) is a statistical technique that tests effects of multiple independent variables on a dependent variable, much like multiple regression; however, path analysis allows for the possibility that variables can be both dependent and independent (i.e., variables can be both affected by MOD and affect other variables) (Fig. 5). The output of path analysis, path coefficients, are standardized regression coefficients that indicate the strength (i.e., maximum of 1) and direction (i.e., positive or negative) of the causal relationships between the variables. To increase statistical power, data in dorsal and ventral striata were combined. This was justified because both regions show a similar direction for the effects of MOD on the parameters analyzed in path analysis: increased DA release, decreased DA uptake, and increased [DA]max.

Fig. 5.

Path analysis model demonstrating the direct relationships between dose, DA release ([DA]p), DA uptake (k), and [DA]max. Values given above each arrow are standardized path coefficients describing each direct effect. Two indirect effects of MOD on [DA]max are described by the two paths from MOD to [DA]max through DA release and DA uptake.

Figure 5 shows the full path analysis model, with arrows demarcating direct relationships between variables and the path coefficient given above each arrow, for 60-minute data. Path analysis of this complete model suggests that MOD exerts almost equal, but opposite, direct effects on DA release (+0.6504; P < 0.0001) and uptake (−0.6710; P < 0.0001). Based on 95% confidence intervals, the effects of MOD on DA release (95% confidence interval, 0.49–0.81) and DA uptake (95% confidence interval, 0.52–0.82) were not significantly different; thus, MOD increases DA release and decreases DA uptake to a similar magnitude. However, DA release exerted a greater direct effect on [DA]max compared with DA uptake, +0.8563 (P < 0.0001) and −0.1623 (P = 0.003), respectively, and the effect of DA release (95% confidence interval, 0.78–0.93) on [DA]max was significantly greater than that of DA uptake (95% confidence interval, 0.05–0.27). The relative contribution of the two paths through DA release or uptake to the [DA]max increase are the indirect effects of MOD on [DA]max. These can be estimated by the products of the direct path coefficients on each path (Fig. 5). For DA release this product is 0.5570, whereas for DA uptake this product is 0.1089. Thus, the indirect effect via DA release is more than 5× greater than that via DA uptake, indicating that MOD-induced increases in [DA]max are primarily mediated via increased DA release.

Alternative path models (i.e., omitting either effects of DA release or uptake on [DA]max from the full model) were conducted, and AIC values, an indicator of information lost by using models to describe data (Anderson, 2008), were compared to determine which model was most appropriate. Omitting effects of DA release or uptake resulted in increased AIC (109.5 and 23.4, respectively), compared with the full model (AIC = 16.4) (Fig. 5), which included both parameters, suggesting that both DA release and uptake together best explain MOD effects on [DA]max. Additionally, the larger AIC calculated after omission of DA release compared with DA uptake suggests that the model omitting the DA release effect is a poorer description of the data, which is consistent with the analysis of path coefficients derived from the full model; this additionally indicated that MOD primarily increases DA release to increase [DA]max.

MOD and Basal DA.

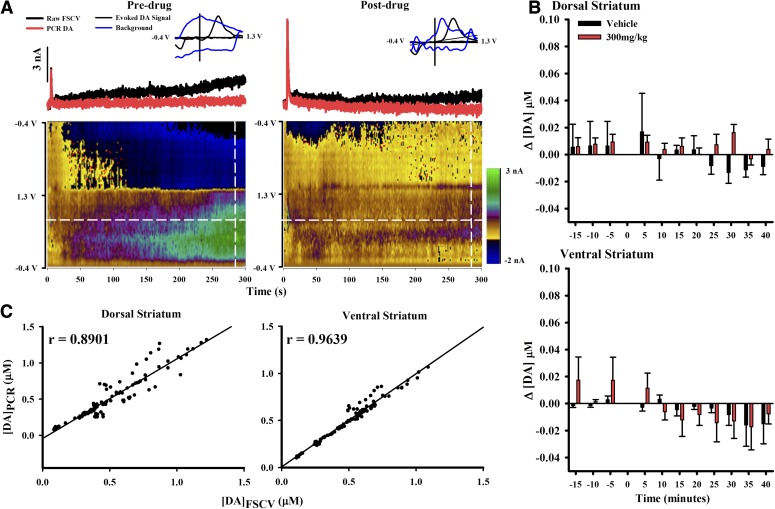

MOD effects on basal DA were assessed by applying a chemometrics analysis called PCR (Hermans et al., 2008; Keithley et al., 2009) to the nonelectrically evoked portion of the raw FSCV recording. Figure 6A shows representative FSCV and PCR recordings for predrug and 60 minutes post-300 mg/kg MOD, the highest dose tested. The raw FSCV recording (Fig. 6A, top; black trace) shows a steady increase in current for both pre- and postdrug conditions (Fig. 6A, left and right sides, respectively). However, the current cannot be attributed solely to DA since the color plot below shows additional electrochemical changes not attributed to DA. Furthermore, individual voltammograms (Fig. 6A, inset) contain other analytes (Fig. 6A, blue) that would mask changes in DA (Fig. 6A, black) if present. PCR resolves DA from these interferents, and the representative traces resolved by PCR (Fig. 6A, red) suggest negligible changes in basal DA with MOD.

Fig. 6.

MOD effects on changes in basal DA in dorsal and ventral striata. (A) The red line displays PCR-resolved DA changes from the black FSCV trace (taken at the white horizontal line) for predrug and 60 minutes postdrug (300 mg/kg). A pseudo-color plot beneath displays all background-subtracted cyclic voltammograms. (Inset) Representative voltammogram (blue) collected at 285 seconds (white vertical line) overlaid with a voltammogram taken at peak electrically evoked signal (black). The y-axis is the normalized current. (B) PCR reveals no significant effect of MOD on basal DA in dorsal (top) and ventral (bottom) striata. Data were analyzed for significance using three-way repeated measures ANOVA (n = 4). (C) Verification of PCR selectivity for the DA component in FSCV recordings. There was a strong correlation between [DA]max measured with FSCV ([DA]FSCV) and PCR ([DA]PCR) in both dorsal (left) and ventral (right) striata.

To assess MOD-induced changes in basal DA within individual 5-minute epochs (Δ[DA]), all data in PCR-resolved DA traces after the electrically evoked response returned to baseline were averaged predrug and for the first 40 minutes of drug response. This time period was selected to examine the initial effects of MOD on basal DA corresponding to the initial robust increase in the amplitude of electrical evoked phasic-like DA signals (Fig. 2). Time 0 minutes was excluded because of noise introduced during drug administration. MOD exerted negligible effects on Δ[DA] in either dorsal (Fig. 6B, top) or ventral (Fig. 6B, bottom) striata. The three-way repeated measures ANOVA yielded no significant effect of time (F10, 90 = 1.80, P = 0.1764), dose (F1, 9 = 0.11, P = 0.7433), and region (F1, 9 = 0.47, P = 0.5118) and no significant time-by-dose-region (F10, 90 = 1.57, P = 0.1287), region-by-dose (F1, 9 = 0.24, P = 0.6384), time-by-dose (F10, 90 = 0.52, P = 0.8748), and time-by-region (F10, 90 = 0.56, P = 0.8392) interactions, indicating that there were no significant effects of MOD on basal DA.

The lack of significant effect of MOD on basal DA assessed by PCR opposes previous findings demonstrating increases in dialysate DA at the same dose (Ferraro et al., 1997; Loland et al., 2012). To address the concern that PCR assigned a portion of the DA signal to a non-DA principal component and that this misplaced DA led to the inability to detect an increase in basal DA with MOD, a linear regression was performed between [DA]max of the electrically evoked response determined from raw FSCV recordings ([DA]FSCV) and from PCR-resolved data ([DA]PCR). The current attributed to the electrically evoked response measured by FSCV over short time scales (i.e., a few seconds) in the anesthetized animal has previously been determined to be primarily due to DA (Wightman et al., 1986). There was a tight association of data to the trend line, as indicated by the significant correlation between [DA]FSCV and [DA]PCR, in both dorsal (Fig. 6C, left; r = 0.8901, P < 0.0001) and ventral (Fig. 6C, right; r = 0.9639, P < 0.0001). Slopes of the trend line were also significantly different from zero in both dorsal (Fig. 6C significant left; b = 1.1012, t = 30.9139, P < 0.0001) and ventral (Fig. 6C, right; b = 0.9890, t = 52.9325, P < 0.0001) striata, indicating significant relationships between [DA]FSCV and [DA]PCR. Thus, this evidence suggests that PCR accurately resolves DA from the mixed analyte signal recorded by FSCV.

MOD Activates DA Transients.

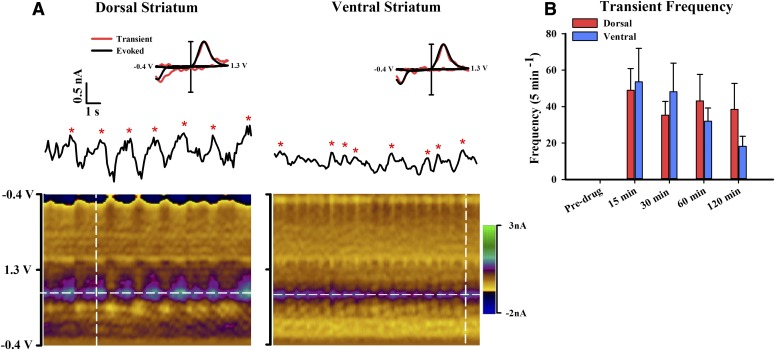

Coadministration of a DA D2 receptor antagonist with a DAT-inhibiting psychostimulant elicits DA transients in urethane-anesthetized rats, without affecting these phasic signals when administered alone (Venton and Wightman, 2007; Park et al., 2010). Presumably, the DA D2 receptor antagonist in the anesthetized preparation prevents the psychostimulant-induced autoinhibition of DA neurons but reveals the psychostimulant-induced activation of burst firing by DA neurons (Shi et al., 2000, 2004). In contrast, psychostimulant-induced activation of DA cell burst firing (Koulchitsky et al., 2012) and DA transients (Stuber et al., 2005; Aragona et al., 2008; Daberkow et al., 2013) in awake animals does not require administration of a DA D2 receptor antagonist. As is similar to other psychostimulants, coadministration of raclopride (2 mg/kg), a DA D2 receptor antagonist, with MOD (30 mg/kg) elicited DA transients in both dorsal (Fig. 7A, left) and ventral (Fig. 7A, right) striata. Asterisks demarcate transients on the FSCV current trace taken at the peak DA oxidative potential. Transients were confirmed to be DA by the electrochemical profile in the pseudo-color plot and comparison of the individual transient voltammogram (Fig. 7A, inset, red) to the electrically evoked DA voltammogram (Fig. 7A, inset, black). Prior to assessing transient frequency at select time points, DA in the raw FSCV traces was resolved with PCR. As shown in Fig. 7B, while no transients were recorded predrug, there was a robust increase in transient frequency 15 minutes postdrug administration and thereafter. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of time on transient frequency (F3, 27 = 11.85, P < 0.0001). However, there was neither a significant effect of region (F1, 9 = 0.18, P = 0.6835) nor a significant time-by-region interaction (F3, 27 = 1.72, P = 0.1932).

Fig. 7.

DA transients are elicited in both dorsal and ventral striata by coadministration of MOD (30 mg/kg) and raclopride (2 mg/kg). (A) Representative recording of DA transients in dorsal (left) and ventral (right) striata. The pseudo-color plots (underneath) serially display all background-subtracted cyclic voltammograms. Transients (denoted by red asterisks) are displayed in the FSCV current trace collected at the peak oxidative potential of DA (white horizontal lines). (Inset) Normalized background-subtracted cyclic voltammograms taken from the electrically evoked response (black lines) and a DA transient (red lines) collected at the white vertical lines in the pseudo-color plots. (B) Average transient frequency per 5-minute epoch for pre- and postdrug administration expressed as mean ± S.E.M. Data were analyzed for significance using two-way repeated measures ANOVA.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate that MOD activates phasic DA signaling in dorsal and ventral striata. Activation was indicated by increased amplitude of electrically evoked phasic-like DA signals, enhanced DA release, inhibited DA uptake, and increased frequency of DA transients. Taken together, these results suggest that activation of phasic DA signaling is a novel mechanism contributing to the therapeutic efficacy of MOD.

MOD and Basal DA.

PCR was used to investigate the effects of MOD on basal DA. This approach revealed no significant changes in basal DA in either dorsal or ventral striata with the highest dose of MOD tested (300 mg/kg). In contrast, ≈3-fold elevation in striatal dialysate DA has been reported for the same dose (Ferraro et al., 1997; Loland et al., 2012). The determination of basal DA is analytically difficult (Sandberg and Garris, 2010), and this discrepancy could be attributed to differences in the two monitoring techniques, which are not fully understood. The use of FSCV coupled to PCR for monitoring basal DA is also an emerging approach. While we demonstrated that PCR was not incorrectly assigning DA to a non-DA principal component in electrically evoked DA signals, the DA concentrations analyzed were much greater than the nonsignificant changes detected in basal DA and recent estimates of basal DA of ≈100 nM (Atcherley et al., 2015). However, PCR has previously detected both increases and decreases in DA levels within these nonsignificant concentration changes and well below 100 nM (≈5–40 nM) (Hart et al., 2014; Roitman et al., 2008). Thus, although PCR appears to have the requisite sensitivity to detect a change in basal DA, a definitive determination of whether MOD acts on basal DA requires further study.

MOD Activates Phasic DA Signaling via Effects at DA Terminals.

Consistent with other DAT-inhibiting psychostimulants, such as cocaine, amphetamine, and methylphenidate (Venton et al., 2006; Ramsson et al., 2011b; Chadchankar et al., 2012; Avelar et al., 2013; Covey et al., 2013; Daberkow et al., 2013), we show that MOD increases DA release and inhibits DA uptake. Thus, our results support the notion that DAT-inhibiting psychostimulants share a common action of altering both presynaptic mechanisms (Covey et al., 2014). How MOD increases DA release is not known. Cocaine and methylphenidate increase DA release via actions on synaptic proteins such as synapsin and α-synuclein, respectively (Venton et al., 2006; Chadchankar et al., 2012), whereas amphetamine increases DA release by inhibiting DA degradation and increasing DA synthesis (Avelar et al., 2013). Further work is needed to determine whether MOD increases DA release by these or other mechanisms.

Because the upward slope of the electrically evoked DA signal reflects the balance between DA release and uptake (Wightman et al., 1988), both presynaptic mechanisms could mediate the observed MOD-induced increases in [DA]max. While indirect evidence suggests that enhanced DA release, compared with inhibited DA uptake, is more responsible for increases in [DA]max elicited by other psychostimulants (Venton et al., 2006; Avelar et al., 2013; Covey et al., 2013; Daberkow et al., 2013), this hypothesis has never been directly tested as was done here. Indeed, path analysis indicated that MOD-induced increases in [DA]max are more strongly mediated by enhanced DA release. The relative contributions of DA release and uptake to [DA]max may inform alterations of DA transients by DAT-inhibiting psychostimulants. For example, while it is thought that increased burst firing of DA neurons drives increased transient frequency and inhibited DA uptake drives increased transient duration, the mechanism underlying increased transient amplitude is debated (Covey et al., 2014). Our results suggest that enhanced DA release, not inhibited DA uptake, is primarily responsible for the increased transient amplitude with DAT-inhibiting psychostimulants. However, caution is urged because this conclusion assumes that the parameters for DA release and uptake obtained from electrically evoked phasic-like DA signals relate to DA transients, and this assumption has been difficult to test.

MOD Activates DA Transients.

We investigated the ability of MOD to elicit DA transients in urethane-anesthetized rats when coadministered with the DA D2 antagonist raclopride. Our findings show that MOD, a low-affinity DAT inhibitor, elicited DA transients in both dorsal and ventral striata at the lowest dose tested (30 mg/kg) when coadministered with raclopride. While MOD increasing the frequency of DA transients is consistent with eliciting burst firing of DA neurons (Covey et al., 2014), the combination of MOD and raclopride could additionally have increased the amplitude of spontaneously occurring (i.e., ongoing) transients above the FSCV detection limit, which may also have contributed to the observed frequency increase. Interestingly, the frequency of DA transients elicited by MOD was similar to that elicited by a high-affinity DAT inhibitor, nomifensine, under similar conditions (Venton and Wightman, 2007), suggesting that the MOD-induced activation is robust. Unfortunately, quantitatively comparing this MOD effect to the psychostimulant-induced activation of DA transients observed in awake rats (Venton and Wightman, 2007; Covey et al., 2013; Daberkow et al., 2013) is tenuous because the use of ralcopride in the present experiment, particularly its blockade of somatodendritic DA autoreceptors, is confounding in isolating the specific effects of MOD. Another potential concern in interpreting the observed MOD-induced activation of DA transients is the profound effects of anesthetics on DA neuron firing (Chiodo, 1988; Kelland et al., 1990). Thus, there is a great need to establish the MOD-induced activation of DA transients in awake animals and in the absence of raclopride.

Addictive Nature of Psychostimulants.

A long-held view in addiction research is that, despite diverse cellular actions, all abused drugs increase brain extracellular DA, with a preferential action in ventral compared with dorsal striata (Di Chiara and Imperato, 1988). More recent work has refined this view by hypothesizing that abused drugs excessively activate phasic DA signaling (Covey et al., 2014), leading to the hijacking of reward circuits and aberrant reward learning (Hyman et al., 2006). While cocaine and amphetamine conform to this hypothesis (Venton and Wightman, 2007; Covey et al., 2013; Daberkow et al., 2013), other mechanisms have been proposed to explain differences in abuse potential for DAT-inhibiting psychostimulants, including DAT affinity (Ritz et al., 1987), speed of brain drug action (Yorgason et al., 2011), and actions via DAT mimicking G protein–coupled receptors, i.e., via the so-called transceptor (Schmitt et al., 2013). Because MOD increases electrically evoked DA levels in the dorsal striatum to a greater extent than in the ventral striatum, it is interesting to speculate that MOD targeting DA signaling in the dorsal striatum contributes to its limited abuse potential (Deroche-Gamonet et al., 2002).

The basis for differential effects of DAT-inhibiting psychostimulants in striatal subregions is not known. Heterogeneity of DA neurons innervating the dorsal and ventral striatum (Doucet et al., 1986; Marshall et al., 1990; Lammel et al., 2008) favors a similar subregional specificity in drug effects, which is not the case. Thus, other factors must be involved. DAT is a potential mediator, and different classes of DAT inhibitors bind to different sites on DAT (Loland et al., 2012; Schmitt et al., 2013). Not unexpectedly, DAT-inhibiting psychostimulants differentially inhibit DA uptake in the striatal subregions; however, these effects appear unrelated to abuse potential (present study; Jones et al., 1995; Wu et al., 2001a; Ramsson et al., 2011a). DA release is another potential mediator, but much less is known about the effects of psychostimulants on this presynaptic mechanism. Clearly, more work is needed to identify the cellular mechanisms distinguishing the differential effects of DAT-inhibiting psychostimulants in the striatum and whether this differential activation involves DA transients.

Clinical Efficacy of MOD.

It is interesting to speculate that activation of phasic DA signaling as demonstrated herein contributes to the clinical efficacy of MOD. For example, therapeutic for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Swanson et al., 2006), MOD may be targeting the insufficient phasic DA signaling proposed to underlie deficits in reward learning observed with this neurodevelopmental pathology (Tripp and Wickens, 2008). A similar activation of phasic DA signaling, albeit from normal levels, may mediate MOD-enhanced cognitive ability in healthy subjects (Müller et al., 2013). Moreover, L-3, 4-dihydroxyphenylalanine has been shown to restore the amplitude of DA transients reduced by long-access cocaine self-administration (Willuhn et al., 2014), and MOD may be acting similarly in psychostimulant abusers (Anderson et al., 2009; Shearer et al., 2009). Finally, while roles for serotonin, norepinephrine, and acetylcholine are well established in sleep-wakefulness (Pace-Schott and Hobson, 2002), more recent evidence implicates DA (Wisor et al., 2001; Dahan et al., 2007) and perhaps phasic DA signaling (Dahan et al., 2007). Consistent with activation of phasic DA signaling as reported herein, MOD-induced wakefulness is dependent on DA receptors (Qu et al., 2008) and an intact striatum (Qiu et al., 2012).

Conclusions

We found that MOD increases the frequency of DA transients, enhances DA release, and inhibits DA uptake in dorsal and ventral striata. Based on these measurements, we propose a mechanism for MOD of activating phasic DA signaling, whereby burst firing of DA neurons and the duration, amplitude, and frequency of DA transients are increased. Further investigation is required to identify the role of these actions in the therapeutic efficacy of MOD.

Abbreviations

- AIC

Akaike information criteria

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- AP

anteroposterior

- CFM

carbon-fiber microelectrode

- DA

dopamine

- [DA]max

maximal concentration of dopamine evoked by electrical stimulation

- [DA]p

concentration of dopamine release per stimulus pulse

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- DV

dorsoventral

- FSCV

fast-scan cyclic voltammetry

- k

first-order rate constant for dopamine uptake

- ML

mediolateral

- MOD

modafinil

- PCR

principal component regression

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Garris.

Conducted experiments: Bobak, Weber, Doellman.

Performed data analysis: Bobak, Weber, Juliano, Schuweiler, Athens, Garris.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Bobak, Weber, Garris, Schuweiler, Juliano.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute for Drug Abuse [Grant DA 036331].

This work was submitted by M.J.B. in partial fulfillment of a M.S. degree and was presented by the authors at the 2015 Annual Meeting for Society of Neuroscience in Chicago. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Anderson AL, Li SH, Biswas K, McSherry F, Holmes T, Iturriaga E, Kahn R, Chiang N, Beresford T, Campbell J, et al. (2012) Modafinil for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 120:135–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AL, Reid MS, Li SH, Holmes T, Shemanski L, Slee A, Smith EV, Kahn R, Chiang N, Vocci F, et al. (2009) Modafinil for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 104:133–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DR. (2008) Model Based Inference in the Life Sciences. A Primer on Evidence, Springer Science Business Media, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Aragona BJ, Cleaveland NA, Stuber GD, Day JJ, Carelli RM, Wightman RM. (2008) Preferential enhancement of dopamine transmission within the nucleus accumbens shell by cocaine is attributable to a direct increase in phasic dopamine release events. J Neurosci 28:8821–8831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atcherley CW, Wood KM, Parent KL, Hashemi P, Heien ML. (2015) The coaction of tonic and phasic dopamine dynamics. Chem Commun (Camb) 51:2235–2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avelar AJ, Juliano SA, Garris PA. (2013) Amphetamine augments vesicular dopamine release in the dorsal and ventral striatum through different mechanisms. J Neurochem 125:373–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barch DM, Carter CS. (2005) Amphetamine improves cognitive function in medicated individuals with schizophrenia and in healthy volunteers. Schizophr Res 77:43–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battleday RM, Brem AK. (2015) Modafinil for cognitive neuroenhancement in healthy non-sleep-deprived subjects: a systematic review. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 25:1865–1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béracochéa D, Cagnard B, Célérier A, le Merrer J, Pérès M, Piérard C. (2001) First evidence of a delay-dependent working memory-enhancing effect of modafinil in mice. Neuroreport 12:375–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadchankar H, Ihalainen J, Tanila H, Yavich L. (2012) Methylphenidate modifies overflow and presynaptic compartmentalization of dopamine via an α-synuclein-dependent mechanism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 341:484–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemelli RM, Willie JT, Sinton CM, Elmquist JK, Scammell T, Lee C, Richardson JA, Williams SC, Xiong Y, Kisanuki Y, et al. (1999) Narcolepsy in orexin knockout mice: molecular genetics of sleep regulation. Cell 98:437–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiodo LA. (1988) Dopamine-containing neurons in the mammalian central nervous system: electrophysiology and pharmacology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 12:49–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey DP, Juliano SA, Garris PA. (2013) Amphetamine elicits opposing actions on readily releasable and reserve pools for dopamine. PLoS One 8:e60763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey DP, Roitman MF, Garris PA. (2014) Illicit dopamine transients: reconciling actions of abused drugs. Trends Neurosci 37:200–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler CA, Walsh JK, Roth T, Hughes RJ, Wright KP, Kingsbury L, Arora S, Schwartz JR, Niebler GE, Dinges DF, U.S. Modafinil in Shift Work Sleep Disorder Study Group (2005) Modafinil for excessive sleepiness associated with shift-work sleep disorder. N Engl J Med 353:476–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daberkow DP, Brown HD, Bunner KD, Kraniotis SA, Doellman MA, Ragozzino ME, Garris PA, Roitman MF. (2013) Amphetamine paradoxically augments exocytotic dopamine release and phasic dopamine signals. J Neurosci 33:452–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan L, Astier B, Vautrelle N, Urbain N, Kocsis B, Chouvet G. (2007) Prominent burst firing of dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area during paradoxical sleep. Neuropsychopharmacology 32:1232–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JJ, Roitman MF, Wightman RM, Carelli RM. (2007) Associative learning mediates dynamic shifts in dopamine signaling in the nucleus accumbens. Nat Neurosci 10:1020–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Saint Hilaire Z, Orosco M, Rouch C, Blanc G, Nicolaidis S. (2001) Variations in extracellular monoamines in the prefrontal cortex and medial hypothalamus after modafinil administration: a microdialysis study in rats. Neuroreport 12:3533–3537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deroche-Gamonet V, Darnaudéry M, Bruins-Slot L, Piat F, Le Moal M, Piazza PV. (2002) Study of the addictive potential of modafinil in naive and cocaine-experienced rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 161:387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, Imperato A. (1988) Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85:5274–5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucet G, Descarries L, Garcia S. (1986) Quantification of the dopamine innervation in adult rat neostriatum. Neuroscience 19:427–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar DM, Seidel WF. (1997) Modafinil induces wakefulness without intensifying motor activity or subsequent rebound hypersomnolence in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 283:757–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro L, Antonelli T, O’Connor WT, Tanganelli S, Rambert FA, Fuxe K. (1997) Modafinil: an antinarcoleptic drug with a different neurochemical profile to d-amphetamine and dopamine uptake blockers. Biol Psychiatry 42:1181–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floresco SB, West AR, Ash B, Moore H, Grace AA. (2003) Afferent modulation of dopamine neuron firing differentially regulates tonic and phasic dopamine transmission. Nat Neurosci 6:968–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace AA, Bunney BS. (1984) The control of firing pattern in nigral dopamine neurons: single spike firing. J Neurosci 4:2866–2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart AS, Rutledge RB, Glimcher PW, Phillips PEM. (2014) Phasic dopamine release in the rat nucleus accumbens symmetrically encodes a reward prediction error term. J Neurosci 3:698–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heien ML, Johnson MA, Wightman RM. (2004) Resolving neurotransmitters detected by fast-scan cyclic voltammetry. Anal Chem 76:5697–5704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans A, Keithley RB, Kita JM, Sombers LA, Wightman RM. (2008) Dopamine detection with fast-scan cyclic voltammetry used with analog background subtraction. Anal Chem 80:4040–4048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ. (2006) Neural mechanisms of addiction: the role of reward-related learning and memory. Annu Rev Neurosci 29:565–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuka T, Murakami M, Yamatodani A. (2008) Involvement of central histaminergic systems in modafinil-induced but not methylphenidate-induced increases in locomotor activity in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 578:209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuka T, Sakamoto Y, Sakurai T, Yamatodani A. (2003) Modafinil increases histamine release in the anterior hypothalamus of rats. Neurosci Lett 339:143–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SR, Garris PA, Wightman RM. (1995) Different effects of cocaine and nomifensine on dopamine uptake in the caudate-putamen and nucleus accumbens. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 274:396–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keithley RB, Heien ML, Wightman RM. (2009) Multivariate concentration determination using principal component regression with residual analysis. Trends Analyt Chem 28:1127–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelland MD, Chiodo LA, Freeman AS. (1990) Anesthetic influences on the basal activity and pharmacological responsiveness of nigrostriatal dopamine neurons. Synapse 6:207–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koulchitsky S, De Backer B, Quertemont E, Charlier C, Seutin V. (2012) Differential effects of cocaine on dopamine neuron firing in awake and anesthetized rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 37:1559–1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczenski R, Segal DS. (2001) Locomotor effects of acute and repeated threshold doses of amphetamine and methylphenidate: relative roles of dopamine and norepinephrine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 296:876–883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczenski R, Segal DS, Aizenstein ML. (1991) Amphetamine, cocaine, and fencamfamine: relationship between locomotor and stereotypy response profiles and caudate and accumbens dopamine dynamics. J Neurosci 11:2703–2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R. (2008) Approved and investigational uses of modafinil : an evidence-based review. Drugs 68:1803–1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kume-Kick J, Rice ME. (1998) Dependence of dopamine calibration factors on media Ca2+ and Mg2+ at carbon-fiber microelectrodes used with fast-scan cyclic voltammetry. J Neurosci Methods 84:55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammel S, Hetzel A, Häckel O, Jones I, Liss B, Roeper J. (2008) Unique properties of mesoprefrontal neurons within a dual mesocorticolimbic dopamine system. Neuron 57:760–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loland CJ, Mereu M, Okunola OM, Cao J, Prisinzano TE, Mazier S, Kopajtic T, Shi L, Katz JL, Tanda G, et al. (2012) R-modafinil (armodafinil): a unique dopamine uptake inhibitor and potential medication for psychostimulant abuse. Biol Psychiatry 72:405–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madras BK, Xie Z, Lin Z, Jassen A, Panas H, Lynch L, Johnson R, Livni E, Spencer TJ, Bonab AA, et al. (2006) Modafinil occupies dopamine and norepinephrine transporters in vivo and modulates the transporters and trace amine activity in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 319:561–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JF, O’Dell SJ, Navarrete R, Rosenstein AJ. (1990) Dopamine high-affinity transport site topography in rat brain: major differences between dorsal and ventral striatum. Neuroscience 37:11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael D, Travis ER, Wightman RM. (1998) Color images for fast-scan CV measurements in biological systems. Anal Chem 70:586A–592A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignot E, Nishino S, Guilleminault C, Dement WC. (1994) Modafinil binds to the dopamine uptake carrier site with low affinity. Sleep 17:436–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RJ. (1998) Design and Analysis of Ecological Experiments, Oxford University Press, Oxford, U.K. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell R. (2001) Path analysis, in Design and Analysis of Ecological Experiments (Scheiner, SM and Gurevitch, J eds) pp 217 – 234 Oxford University Press, Inc., New York. [Google Scholar]

- Müller U, Rowe JB, Rittman T, Lewis C, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ. (2013) Effects of modafinil on non-verbal cognition, task enjoyment and creative thinking in healthy volunteers. Neuropharmacology 64:490–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace-Schott EF, Hobson JA. (2002) The neurobiology of sleep: genetics, cellular physiology and subcortical networks. Nat Rev Neurosci 3:591–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pack AI, Black JE, Schwartz JR, Matheson JK. (2001) Modafinil as adjunct therapy for daytime sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164:1675–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Aragona BJ, Kile BM, Carelli RM, Wightman RM. (2010) In vivo voltammetric monitoring of catecholamine release in subterritories of the nucleus accumbens shell. Neuroscience 169:132–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. (1986) The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, Academic Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips PE, Stuber GD, Heien ML, Wightman RM, Carelli RM. (2003) Subsecond dopamine release promotes cocaine seeking. Nature 422:614–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu MH, Liu W, Qu WM, Urade Y, Lu J, Huang ZL. (2012) The role of nucleus accumbens core/shell in sleep-wake regulation and their involvement in modafinil-induced arousal. PLoS One 7:e45471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu WM, Huang ZL, Xu XH, Matsumoto N, Urade Y. (2008) Dopaminergic D1 and D2 receptors are essential for the arousal effect of modafinil. J Neurosci 28:8462–8469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsson ES, Covey DP, Daberkow DP, Litherland MT, Juliano SA, Garris PA. (2011a) Amphetamine augments action potential-dependent dopaminergic signaling in the striatum in vivo. J Neurochem 117:937–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsson ES, Howard CD, Covey DP, Garris PA. (2011b) High doses of amphetamine augment, rather than disrupt, exocytotic dopamine release in the dorsal and ventral striatum of the anesthetized rat. J Neurochem 119:1162–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repantis D, Schlattmann P, Laisney O, Heuser I. (2010) Modafinil and methylphenidate for neuroenhancement in healthy individuals: a systematic review. Pharmacol Res 62:187–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz MC, Lamb RJ, Goldberg SR, Kuhar MJ. (1987) Cocaine receptors on dopamine transporters are related to self-administration of cocaine. Science 237:1219–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roitman MF, Wheeler RA, Wightman RM, Carelli RM. (2008) Real-time chemical responses in the nucleus accumbens differentiate rewarding and aversive stimuli. Nat Neurosci 12:1376–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg SG, Garris PA. (2010) Neurochemistry of addiction: monitoring essential neurotransmitters of addiction, in Advances in the Neuroscience of Addiction (Kuhn CM, Koob GF, eds) pp 101–136, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt KC, Rothman RB, Reith ME. (2013) Nonclassical pharmacology of the dopamine transporter: atypical inhibitors, allosteric modulators, and partial substrates. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 346:2–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W, Dayan P, Montague PR. (1997) A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science 275:1593–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer J, Darke S, Rodgers C, Slade T, van Beek I, Lewis J, Brady D, McKetin R, Mattick RP, Wodak A. (2009) A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil (200 mg/day) for methamphetamine dependence. Addiction 104:224–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi WX, Pun CL, Zhang XX, Jones MD, Bunney BS. (2000) Dual effects of D-amphetamine on dopamine neurons mediated by dopamine and nondopamine receptors. J Neurosci 20:3504–3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi WX, Pun CL, Zhou Y. (2004) Psychostimulants induce low-frequency oscillations in the firing activity of dopamine neurons. Neuropsychopharmacology 29:2160–2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuber GD, Wightman RM, Carelli RM. (2005) Extinction of cocaine self-administration reveals functionally and temporally distinct dopaminergic signals in the nucleus accumbens. Neuron 46:661–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JM, Greenhill LL, Lopez FA, Sedillo A, Earl CQ, Jiang JG, Biederman J. (2006) Modafinil film-coated tablets in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study followed by abrupt discontinuation. J Clin Psychiatry 67:137–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanganelli S, Fuxe K, Ferraro L, Janson AM, Bianchi C. (1992) Inhibitory effects of the psychoactive drug modafinil on gamma-aminobutyric acid outflow from the cerebral cortex of the awake freely moving guinea-pig. Possible involvement of 5-hydroxytryptamine mechanisms. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 345:461–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripp G, Wickens JR. (2008) Research review: dopamine transfer deficit: a neurobiological theory of altered reinforcement mechanisms in ADHD. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49:691–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venton BJ, Seipel AT, Phillips PE, Wetsel WC, Gitler D, Greengard P, Augustine GJ, Wightman RM. (2006) Cocaine increases dopamine release by mobilization of a synapsin-dependent reserve pool. J Neurosci 26:3206–3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venton BJ, Wightman RM. (2007) Pharmacologically induced, subsecond dopamine transients in the caudate-putamen of the anesthetized rat. Synapse 61:37–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward CP, Harsh JR, York KM, Stewart KL, McCoy JG. (2004) Modafinil facilitates performance on a delayed nonmatching to position swim task in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 78:735–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wightman RM, Amatore C, Engstrom RC, Hale PD, Kristensen EW, Kuhr WG, May LJ. (1988) Real-time characterization of dopamine overflow and uptake in the rat striatum. Neuroscience 25:513–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wightman RM, Kuhr WG, Ewing AG. (1986) Voltammetric detection of dopamine release in the rat corpus striatum. Ann N Y Acad Sci 473:92–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willuhn I, Burgeno LM, Groblewski PA, Phillips PE. (2014) Excessive cocaine use results from decreased phasic dopamine signaling in the striatum. Nat Neurosci 17:704–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise MS, Arand DL, Auger RR, Brooks SN, Watson NF, American Academy of Sleep Medicine (2007) Treatment of narcolepsy and other hypersomnias of central origin. Sleep 30:1712–1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisor JP, Nishino S, Sora I, Uhl GH, Mignot E, Edgar DM. (2001) Dopaminergic role in stimulant-induced wakefulness. J Neurosci 21:1787–1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Reith ME, Kuhar MJ, Carroll FI, Garris PA. (2001a) Preferential increases in nucleus accumbens dopamine after systemic cocaine administration are caused by unique characteristics of dopamine neurotransmission. J Neurosci 21:6338–6347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Reith ME, Wightman RM, Kawagoe KT, Garris PA. (2001b) Determination of release and uptake parameters from electrically evoked dopamine dynamics measured by real-time voltammetry. J Neurosci Methods 112:119–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorgason JT, Jones SR, España RA. (2011) Low and high affinity dopamine transporter inhibitors block dopamine uptake within 5 sec of intravenous injection. Neuroscience 182:125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolkowska D, Jain R, Rothman RB, Partilla JS, Roth BL, Setola V, Prisinzano TE, Baumann MH. (2009) Evidence for the involvement of dopamine transporters in behavioral stimulant effects of modafinil. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 329:738–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]