Abstract

Background: Picky eating has been associated with lower weight status and limited food intake and variety in childhood. Little is known about how the persistence of picky eating in childhood is associated with changes in weight and food intake from childhood into adolescence.

Objective: We determined whether picky eating identified in childhood was related to growth, nutrition, and parental use of pressure over a 10-y period.

Design: Non-Hispanic white girls (n = 181) participated in a longitudinal study and were assessed biannually from ages 5 to 15 y. The Child Feeding Questionnaire was used to classify girls as persistent picky eaters or nonpicky eaters and to assess parental use of pressure to eat. Height and weight were measured to calculate body mass index (BMI) z scores at each occasion. Three 24-h dietary recalls obtained at each occasion were used to determine intakes of fruit and vegetables. With the use of repeated-measures analyses, differences between persistent picky eaters and nonpicky eaters in BMI z scores, dietary intake, and use of pressure were examined.

Results: From ages 5 to 15 y, persistent picky eaters (n = 33; 18%) had lower BMI (tracking at the 50th percentile) than did nonpicky eaters (n = 148; tracking at the 65th percentile) (P = 0.02). Persistent picky eaters were less likely to be overweight into adolescence. Both groups consumed less than the recommended amounts of fruit and vegetables, although persistent picky eaters had lower intakes of vegetables than did nonpicky eaters at all time points (P = 0.02). Persistent picky eaters also received higher amounts of pressure (P = 0.01).

Conclusions: Findings that persistent picky eaters were within the normal weight range, were less likely to be overweight, and had similar fruit intakes to those of nonpicky eaters suggest that higher parental concerns about persistent picky eaters are unwarranted. All parents and children could benefit from evidence-based anticipatory guidance on alternatives to coercive feeding practices to increase fruit and vegetable consumption.

Keywords: children, diet, growth, picky eating, weight

INTRODUCTION

Picky eating includes the rejection of familiar foods, which can result in a habitual diet with limited variety (1, 2). Picky eating is typically assessed with the use of maternal subjective reports (3), and parents’ questions and concerns about picky eating are common at well-child clinic visits. Although picky eating is not always taken seriously, picky eaters’ limited food repertoires can result in inadequate intakes of vitamins and minerals (1, 4) especially if they are reported to routinely reject many foods or consume small amounts of food.

Examinations of the relations between children’s picky eating and weight status have revealed some cause for concern, whereby children who are picky eaters tend to have lower BMI than that of nonpicky eaters (5–8). Earlier studies have indicated that picky eaters are twice as likely to be underweight as nonpicky eaters are, although findings have been inconsistent (1, 9). An important limitation is that nearly all data on picky eating are from cross-sectional studies, which do not allow for the assessment of reverse causality. In previous research on picky eating that was conducted in the current study sample, girls who were picky eaters at age 7 y had lower BMIs than did nonpicky eaters at age 9 y; however, none of the girls were underweight, and they were also less likely to be overweight (1). Few studies have assessed the long-term effects of persistent picky eating in childhood on nutrition and growth outcomes.

The current study used longitudinal data to investigate whether persistent picky eating in childhood is associated with adverse weight outcomes or lower fruit and vegetable intakes into adolescence. In recent decades, excessive food intake and obesity have emerged as major health problems in children and adults alike. It is possible that, in this context, eating behaviors that may fuel parental concerns about children’s picky eating, such as consuming a limited variety and eating small amounts of food, could actually be protective against excessive weight gain and obesity. Although there have been data that suggested that some indicators of diet quality, including fruit and vegetable intakes, are low in picky eaters, findings from the NHANES revealed that the majority of children have diets that are too low in fruit and vegetables (10, 11).

The primary aim of this study was to determine whether girls who were persistent picky eaters in childhood differed from nonpicky eaters in BMI, overweight status, and fruit and vegetable intakes into adolescence (1). A secondary aim was to explore whether there were differences in the use of pressure to eat by mothers of persistent picky eaters than of nonpicky eaters to provide information about whether differences in the pressure to eat may have contributed to differences in fruit and vegetable intakes.

METHODS

Subjects

Participants were 197 non-Hispanic white girls who were living in central Pennsylvania and were recruited as part of a longitudinal study on growth and development; the sample was not recruited on the basis of weight status or a concern about weight. Families with age-eligible girls within a 5-county radius were identified with the use of available marketing information (Metromail Inc.). The families received mailings that provided information about the study and were recruited in 1996–1997 through the use of follow-up phone calls. Girls were included in the study if they were living with 2 biological parents, had no severe food allergies or chronic medical conditions that would affect food intake, and had no dietary restrictions involving animal products. A description of the study sample has been previously reported (2).

Design and procedures

Data were collected on 6 occasions across a 10-y period with a 2-y interval between assessments; girls were aged 5 y at baseline and aged 15 y at the final assessment. The participant flow is presented in Supplemental Figure 1. In the 197 mother-daughter dyads at baseline, 181 and 163 dyads remained in the study until ages 9 and 15 y, respectively, which represented a retention rate of 92% and 85%, respectively. Attrition was primarily because of family relocation outside of the study area. At each time interval, girls or their mothers completed a series of questionnaires during a scheduled visit to the laboratory. Girls’ anthropometric data were also collected. The Pennsylvania State University Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures, and mothers provided consent for their family’s participation in the study before the initiation of data collection.

Measures

Picky eating

Girls’ picky eating was assessed at ages 5, 7, and 9 y with the use of the Child Feeding Questionnaire (CFQ) (1, 12). The picky-eating subscale measured mothers’ reports of how they perceived their children’s willingness to eat foods offered and included the following 3 items: 1) “my child’s diet consists of only a few foods” 2) “my child is unwilling to eat many of the foods that our family eats at mealtimes” and 3) “my child is fussy or picky about what she eats”. All items were measured with the use of a 5-point Likert-type scale; responses ranged from disagree to agree. A mean score for picky eating was calculated at each occasion. The internal consistency of the picky-eating subscale was α = 0.85 at each time point (1). Persistent picky eating from ages 5 to 9 y was defined as having a mean picky eating score >3.00 at ≥2 of 3 time points.

Pressure to eat

Mothers’ use of pressure to eat was also assessed at girls’ ages 5, 7, and 9 y with the use of the CFQ pressure subscale; the subscale measured the extent to which mothers pressured their children to consume foods and included the following 4 items: 1) “my child should always eat all of the food on her plate” 2) “I have to be especially careful to make sure my child eats enough” 3) “if my child says ‘I'm not hungry,’ I try to get her to eat anyway” and 4) “if I did not guide or regulate my child's eating, she would eat much less than she should”. All items were measured with the use of a 5-point Likert-type scale; responses ranged from disagree to agree. A mean score for pressure to eat was calculated at each occasion. The internal consistency of items on this subscale was α = 0.73 at each time point (1).

Anthropometric measures

Girls’ heights and weights were measured in triplicate at all 6 occasions from ages 5 to 15 y. Standing height was measured with the use of a wall-mounted stadiometer to the nearest 0.1 cm (Shorr Productions Stadiometer; Irwin Shorr). Body weight was measured with the use of an electronic scale to the nearest 0.1 kg (Seca Electronic Scale; Seca Corp.) (13). BMI z scores and BMI percentiles were calculated with the use of 2000 CDC growth charts (14).

Dietary intake

Twenty-four–hour dietary recall interviews were conducted by telephone at the Dietary Assessment Center at the Pennsylvania State University as described by Savage et al. (15). Trained staff administered interviews with the use of the computer-assisted Nutrition Data System for Research (NDS-R) software (database version 4.01_30; Nutrition Coordinating Center, University of Minnesota). The NDS-R software provides a structured, guided, controlled platform in which questions and probes are standard, and the process of conducting the 24-h recall is standard. The NDS-R time-related database updates analytic data while maintaining nutrient profiles that are true to the bastion used for data collection. Reliability in interviewers is based on an interclass correlation ≥0.95 (15, 16).

Girls’ dietary intakes were provided for 2 weekdays and 1 weekend day, which were randomly selected within a 2-wk period. At ages 5, 7, and 9 y, mothers served as the primary reporters of girls’ intakes, and girls were present to help verify the data . At ages 11, 13, and 15 y, girls served as the primary reporters with mothers participating in the interview as needed. Food-portion posters (2D Food Portion Visual; Nutrition Consulting Enterprises) were used to assist in the estimation of food amounts.

Fruit and vegetable intakes were averaged across the 3 d to estimate the number of cup equivalents that were reported to have been consumed on the basis of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (11, 17) and the USDA Food Guide Pyramid guidelines (15, 18). French fries and potatoes were excluded from the vegetable score for the analyses (2).

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed with the use of SAS software (version 9.1, 2001; SAS Institute Inc.) (19). Each outcome variable was assessed for normality. To test for group differences in girls’ BMI trajectories over time, BMI z scores were used; for illustrative purposes only, BMI percentiles are presented with the use of CDC growth charts (14). A mixed-modeling approach (PROC MIXED; SAS Institute Inc.) was used to assess the effects of picky eating status (persistent picky eaters compared with nonpicky eaters) on changes in BMI z scores and selected indicators of dietary intake and pressure to eat. Mixed modeling is a useful tool for analyzing repeated measures over time, and a main advantage of the tool is its ability to retain cases with one or more missing data points (20). For the models that predicted BMI z scores, intakes of fruit and vegetables, and the pressure to eat, an unstructured covariance matrix was selected; main effects of the picky-eating group, time, and interactions of picky-eating group × time were tested. Potential confounders were not included in the final models because these were a focus of a previous publication that was conducted in the same sample (2). Group differences in the prevalence of underweight (BMI <5th percentile) and overweight or obese (BMI ≥85th percentile) were tested with the use of chi-square tests. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

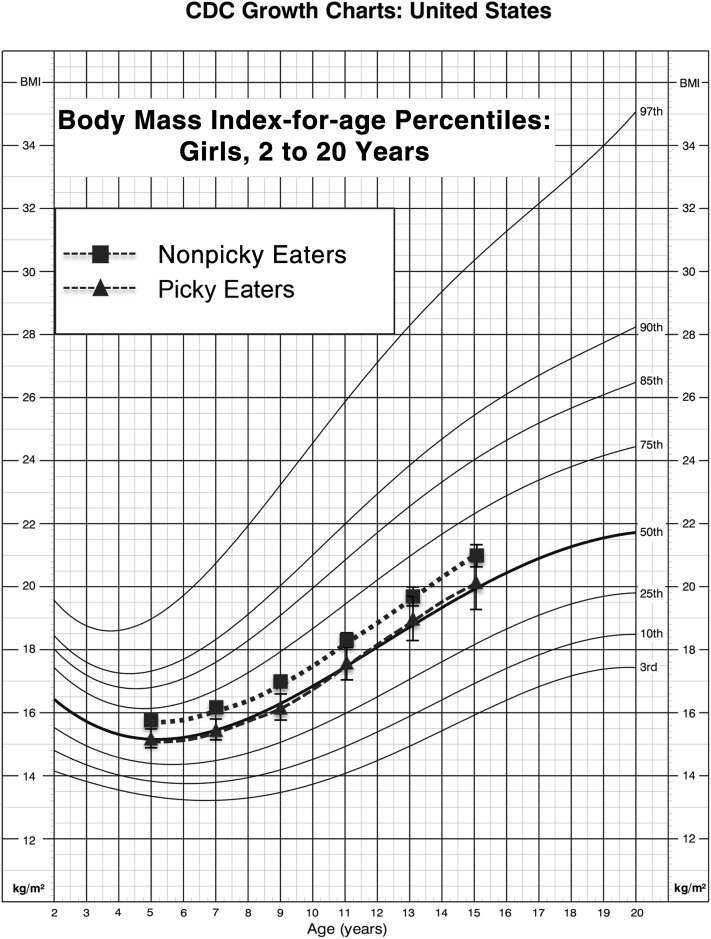

In this sample, 18% of girls were classified as persistent picky eaters on the basis of our criterion of picky eating at ≥2 of 3 measurement time points (n = 33). Girls who were persistent picky eaters during childhood had significantly lower BMI z scores than those of nonpicky eaters at all time points (P = 0.02). The rate of weight change from childhood into adolescence (i.e., an increase in BMI z scores) did not differ between persistent picky eaters and nonpicky eaters; there was no main effect of time, and there was no interaction of picky-eating group × time. As illustrated in Figure 1, the mean BMI percentile in girls who were persistent picky eaters tracked along the 50th percentile, whereas, in contrast, the mean BMI percentile of nonpicky eaters tracked at the 65th percentile. Underweight was rare; only 2 persistent picky eaters were classified as underweight at each time point, and there were no differences between groups in the number of girls who were underweight. The prevalence of overweight and obesity (BMI ≥85th percentile) in nonpicky eaters was 21%, 22%, and 36% at ages 5, 7, and 9 y, respectively, and 34%, 28%, and 24% at ages 11, 13, and 15 y, respectively. In contrast, the percentage of overweight and obesity in persistent picky eaters was never >2%.

FIGURE 1.

BMI percentiles from ages 5 to 15 y in girls classified as picky eaters (n = 29) compared with those classified as nonpicky eaters (n = 134) plotted on the CDC growth-reference chart (14). This CDC, Department of Health and Human Services, growth chart is made available under the Open Database License (http://opendatacommons.org/licenses/odbl/1.0/). Any rights in individual contents of the database are licensed under the Database Contents License (http://opendatacommons.org/licenses/dbcl/1.0/).

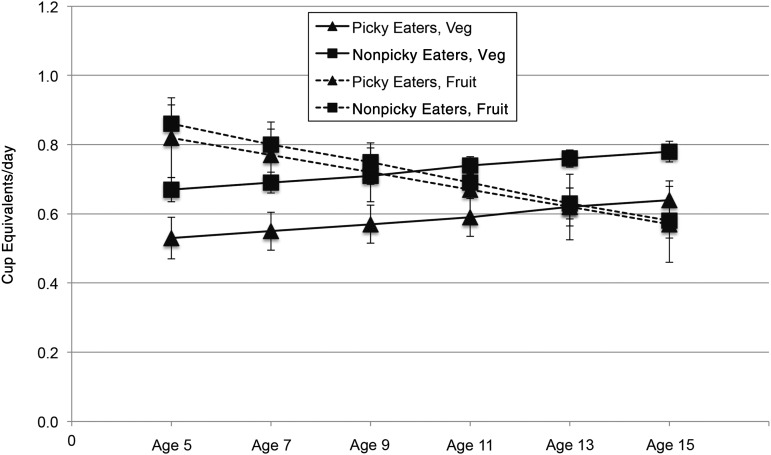

Mean fruit and vegetable intakes in cup equivalents per day are presented in Figure 2 and revealed that, in both groups, reported mean intakes of fruit and vegetables were below the recommended 2-cup equivalents/d for fruit and 3-cup equivalents/d for vegetables (11). There were no differences between persistent picky eaters and nonpicky eaters in fruit intake [0.70 ± 0.10 (mean ± SE) compared with 0.72 ± 0.05-cup equivalents/d]; on average, both groups decreased fruit intake with increasing age (P < 0.01). The rate of decrease in fruit intake with age was similar for persistent picky eaters and nonpicky eaters because there was no interaction of picky-eating group × time. Girls who were persistent picky eaters consumed significantly fewer vegetables per day than nonpicky eaters did at all time points (0.57 ± 0.06 compared with 0.73 ± 0.03-cup equivalents/d) (P = 0.02). There was no main effect of time and no interaction of picky-eating group × time.

FIGURE 2.

Mean ± SE intakes of fruit and veg (cup equivalents per day) from ages 5 to 15 y in girls classified as picky eaters (n = 29) compared with those classified as nonpicky eaters (n = 134). For veg, there was a significant main effect of the group on cup equivalents per day [P = 0.02; repeated-measures analysis (PROC MIXED; SAS Institute Inc.)]; neither the main effect of time nor the group × time interaction was significant. For fruit, there was a significant main effect of time on cup equivalents per day (P < 0.01); both the main effect of the group and the group × time interaction were NS. The 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends 2-cup equivalents fruit/d and 3-cup equivalents veg/d for adolescents (0.5-cup equivalents is ∼85–125 g) (11). Veg, vegetables.

Analyses of pressure-to-eat scores revealed that mothers of girls who were persistent picky eaters reported the use of higher amounts of pressure to eat than did mother of girls who were nonpicky eaters; there was a significant main effect of the picky-eating group on pressure scores (P < 0.01). Maternal reports of pressure to eat declined in both groups over time (P < 0.01). There was no interaction of picky-eating group × time.

DISCUSSION

In this longitudinal sample, 18% of girls were classified as persistent picky eaters in childhood, and although these girls had a lower weight status in childhood than nonpicky eaters did, both groups had mean BMIs that tracked within the normal range into adolescence. Although persistent picky eaters also had consistently lower intakes of vegetables per day than nonpicky eaters did, the difference was small, and both groups consumed substantially less than the recommended amounts of fruit and vegetables per day. Results that signified that persistent picky eaters were growing normally and were less likely to be overweight than nonpicky eaters were, in combination with no clinically meaningful differences in fruit and vegetable intakes, indicated that persistent picky eating might have some adaptive value in the current food environment (1, 21, 22).

Picky eating in children is often of concern to parents who worry that a habitual diet with limited variety will adversely affect children’s growth and development. Previous studies in early childhood have shown that picky eaters were more likely to have lower BMI than that of nonpicky eaters (5, 6, 8). In contrast, BMI data from our longitudinal sample showed that persistent picky eating in childhood was not related to risk of being underweight in childhood or in adolescence. Girls who were persistent picky eaters were not underweight but had a lower weight status than that of nonpicky eaters in childhood, and persistent picky eaters continued to consistently track near the 50th percentile from ages 5 to 15 y (1). These results are in agreement with studies in school-age children, thereby indicating that maternal reports of picky eating are not associated with poor growth outcomes (1, 6, 23).

Both persistent picky eaters and nonpicky eaters consumed substantially less than the recommended amounts of fruit and vegetables per day; on average, persistent picky eaters and nonpicky eaters consumed <50% of the recommended amount of fruit (∼2-cup equivalents/d) and <25% of the recommended amount of vegetables (∼3-cup equivalents/d). Although girls who were persistent picky eaters reported even lower intakes of vegetables, differences between groups were marginal. These findings are in agreement with those from the NHANES in this age group and with those from previous studies (10, 11, 24). Overall, persistent picky eating was associated with problems in food intake that were similar to the national trends in children and adolescents.

These findings, which showed that persistent picky eating in childhood was not associated with adverse weight outcomes during childhood and adolescence or with intakes of fruit and vegetables that were drastically different from the national trends, should ease the anxiety of parents. Parental concern over children’s eating and weight status can elicit feeding practices with unintended negative consequences (25). In the current study, mothers who perceived that their daughters were persistent picky eaters were more likely to use pressure to eat (1), and experimental findings indicated that higher amounts of pressure to eat are related to lower intakes of foods that children are pressured to eat. The association between persistent picky eating and the use of pressure suggests that the relation is most likely bidirectional with picky eaters receiving more pressure in response to their reluctance to eat and pressure fueling their dislikes for foods that they are being pressured to eat. In the current study, nonpicky eaters were also receiving a modicum of pressure, which suggested that alternatives to pressure to promote intakes of fruit and vegetables, including the use of repeated exposure, parental modeling, and pairing foods with preferred flavors or contexts, can be more effective at increasing fruit and vegetable intakes in all children (1, 26–28).

Strengths of the current study include the use of longitudinal data to define persistent picky eating in girls and to examine relations with weight status from childhood into adolescence. This use of longitudinal data also supports the efficacy of a simple 3-item scale for use during childhood as a screening tool for possible problem eating behaviors; the CFQ was able to identify girls as picky eaters who showed clear and predicted differences in vegetable intake and weight status compared with those of nonpicky eaters. In addition, the study followed girls from early childhood through a period of dramatic growth and developmental change. This study is not without limitations. First, the sample was relatively small and racially and demographically homogenous and included only girls; the findings cannot be generalized to boys or to other racial and socioeconomic groups. Another potential limitation is that the study initiation occurred in early childhood rather than in infancy; by age 5 y, girls who were picky eaters in the current study already had lower weight status than that of nonpicky eaters. Additional studies are needed to determine temporal relations between the onset of picky eating and lower weight status and parental use of pressure and to better define the antecedents of problem eating behaviors.

In conclusion, persistent picky eating in childhood is related to lower but normal weight status in both childhood and adolescence from ages 5 to 15 y and a lower prevalence of overweight and obesity than in nonpicky eaters. Both persistent picky eaters and nonpicky eaters had similarly low intakes of fruit and vegetables, and this result underscores findings from previous studies that have indicated the need to increase the consumption of fruit and vegetables in all children (11, 29). These findings suggest that, in the absence of other indicators, parental anxiety over children’s picky eating is not warranted. Rather than pressuring children to eat their vegetables, alternatives to the use of pressure should be encouraged. For example, previous findings have suggested that parents who model fruit and vegetable consumption and provide repeated exposure to healthy foods increase food acceptance in their children (1, 27, 30).

Acknowledgments

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—PKB and LLB: were responsible for the study concept and design; EEH and MEM: conducted the statistical analyses; JSS: was responsible for the data collection; and all authors: contributed to the interpretation of the results and manuscript preparation and read and approved the final manuscript. None of the authors had a financial or personal conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Galloway AT, Fiorito L, Lee Y, Birch LL. Parental pressure, dietary patterns, and weight status among girls who are “picky eaters”. J Am Diet Assoc 2005;105:541–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galloway AT, Lee Y, Birch LL. Predictors and consequences of food neophobia and pickiness in young girls. J Am Diet Assoc 2003;103:692–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor CM, Wernimont SM, Northstone K, Emmett PM. Picky/fussy eating in children: review of definitions, assessment, prevalence and dietary intakes. Appetite 2015;95:349–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xue Y, Zhao A, Cai L, Yang B, Szeto IM, Ma D, Zhang Y, Wang P. Growth and development in Chinese pre-schoolers with picky eating behaviour: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0123664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubois L, Farmer A, Girard M, Peterson K, Tatone-Tokuda F. Problem eating behaviors related to social factors and body weight in preschool children: a longitudinal study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2007;4:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antoniou EE, Roefs A, Kremers SP, Jansen A, Gubbels JS, Sleddens EF, Thijs C. Picky eating and child weight status development: a longitudinal study. J Hum Nutr Diet 2016;29:298–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekstein S, Laniado D, Glick B. Does picky eating affect weight-for-length measurements in young children? Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2010;49:217–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Barse LM, Tiemeier H, Leermakers ET, Voortman T, Jaddoe VW, Edelson LR, Franco OH, Jansen PW. Longitudinal association between preschool fussy eating and body composition at 6 years of age: The Generation R Study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2015;12:153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright CM, Parkinson KN, Shipton D, Drewett RF. How do toddler eating problems relate to their eating behavior, food preferences, and growth? Pediatrics 2007;120:e1069–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Cancer Institute. Usual dietary intakes: food intakes, U.S. population, 2007-10 [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health, Division of Cancer Control & Population Sciences. May 2015 [cited 2016 Jul 15]. Epidemiology and Genomics Research Program. Available from: http://epi.grants.cancer.gov/diet/usualintakes/pop/2007-10/.

- 11.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans [Internet]. Washington (DC): Department of Health and Human Services and the US Department of Agriculture. 8th ed. December 2015 [cited 2016 Apr 21]. Available from: http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/.

- 12.Birch LL, Fisher JO, Grimm-Thomas K, Markey CN, Sawyer R, Johnson SL. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Child Feeding Questionnaire: a measure of parental attitudes, beliefs and practices about child feeding and obesity proneness. Appetite 2001;36:201–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lohman TRA, Martorell R. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Champaign (IL): Human Kinetics; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R, Mei Z, Curtin LR, Roche AF, Johnson CL. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data 2000;314:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savage JS, Marini M, Birch LL. Dietary energy density predicts women’s weight change over 6 y. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88:677–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smicklas-Wright H, Ledikwe J. Dietary intake assessment: methods for adults. 3rd ed. In: CB, editor. Handbook of nutrition and food. Boca Raton (FL): Taylor and Francis; 2001. p. 477–93.

- 17.US Department of Health and Human Services and the US Department of Agriculture. Dietary guidelines for Americans. 6th ed. Washington (DC): US Government Printing Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cleveland LE, Cook DA, Krebs-Smith SM, Friday J. Method for assessing food intakes in terms of servings based on food guidance. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;65(4 Suppl):1254S–63S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.SAS Institute Inc. Statistical analysis software. Cary (NC): SAS Institute Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singer J. Using SAS PROC MIXED to fit multilevel models, hierarchical models, and individual growth models. J Educ Behav Stat 1998;23:323–55. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Birch LL, Doub AE. Learning to eat: birth to age 2 y. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;99:723S–8S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Popkin BM. The nutrition transition and obesity in the developing world. J Nutr 2001;131:871S–3S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mascola AJ, Bryson SW, Agras WS. Picky eating during childhood: a longitudinal study to age 11 years. Eat Behav 2010;11:253–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor CM, Northstone K, Wernimont SM, Emmett PM. Picky eating in preschool children: associations with dietary fibre intakes and stool hardness. Appetite 2016;100:263–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Francis LA, Hofer SM, Birch LL. Predictors of maternal child-feeding style: maternal and child characteristics. Appetite 2001;37:231–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson SL. Developmental and environmental influences on young children’s vegetable preferences and consumption. Adv Nutr 2016;7:220S–31S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wardle J, Cooke LJ, Gibson EL, Sapochnik M, Sheiham A, Lawson M. Increasing children’s acceptance of vegetables; a randomized trial of parent-led exposure. Appetite 2003;40:155–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savage JS, Peterson J, Marini M, Bordi PL Jr, Birch LL. The addition of a plain or herb-flavored reduced-fat dip is associated with improved preschoolers’ intake of vegetables. J Acad Nutr Diet 2013;113:1090–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slining MM, Mathias KC, Popkin BM. Trends in food and beverage sources among US children and adolescents: 1989-2010. J Acad Nutr Diet 2013;113:1683–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Birch LL, Marlin DW. I don’t like it; I never tried it: effects of exposure on two-year-old children’s food preferences. Appetite 1982;3:353–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]