Abstract

Background: Mastitis is a painful problem experienced by breastfeeding women, especially in the first few weeks postpartum. There have been limited studies of the incidence of mastitis from traditionally breastfeeding societies in South Asia. This study investigated the incidence, determinants, and management of mastitis in the first month postpartum, as well as its association with breastfeeding outcomes at 4 and 6 months postpartum, in western Nepal.

Subjects and Methods: Subjects were a subsample of 338 mothers participating in a larger prospective cohort study conducted in 2014 in western Nepal. Mothers were interviewed during the first month postpartum and again at 4 and 6 months to obtain information on breastfeeding practices. The association of mastitis and determinant variables was investigated using multivariable logistic regression, and the association with breastfeeding duration was examined using Kaplan–Meier estimation.

Results: The incidence of mastitis was 8.0% (95% confidence interval, 5.1%, 10.8%) in the first month postpartum. Prelacteal feeding (adjusted odds ratio = 2.76; 95% confidence interval, 1.03, 7.40) and cesarean section (adjusted odds ratio = 3.52; 95% confidence interval, 1.09, 11.42) were associated with a higher likelihood of mastitis. Kaplan–Meier estimation showed no significant difference in the duration of exclusive breastfeeding among the mothers who experienced an episode of mastitis and those who did not.

Conclusions: Roughly one in 10 (8.0%) women experienced mastitis in the first month postpartum, and there appeared to be little effect of mastitis on breastfeeding outcomes. Traditional breastfeeding practices should be encouraged, and the management of mastitis should be included as a part of lactation promotion.

Introduction

Maternal problems during breastfeeding commonly have been reported to be one of the reasons for early discontinuation of breastfeeding.1,2 Studies from developed countries, including Australia, have reported sore nipples, breast pain, and mastitis as common problems during breastfeeding.2,3

Mastitis is a major problem experienced by breastfeeding women, especially in the first few weeks postpartum, and mastitis incidence rates of around 20% have been reported in developed countries,4–6 but with wide variations among studies. For example, Vogel et al.4 reported a 12-month incidence rate of 23.7% (n = 350) among a cohort of women in New Zealand, whereas a much lower incidence rate of 9.5% (n = 946) was reported for a cohort of women followed up for 3 months in the United States.7 The time of occurrence is an important consideration when measuring the incidence of mastitis, and several studies have reported that the incidence is highest in the first few weeks postpartum6,8 and that rates decline thereafter. For instance, Scott et al.6 reported a 6-month incidence of 18% among a Scottish cohort, of which 53% of the cases (30 of 57) occurred in the first 4 weeks postpartum. Similarly, Amir et al.8 reported a 17.3% (n = 1,193) cumulative incidence in the first 6 weeks postpartum, of which 53% of cases occurred in the first 4 weeks.

Although many factors have been associated with lactation mastitis,5,9 knowledge of the cause and disease process remains limited. The most convincing and acceptable disease process is insufficient removal of breastmilk leading to milk stasis.10 Early diagnosis and treatment of mastitis are important; if inflammation persists, it can block the lactiferous tissues and cause milk stasis, leading to breast abscess and sepsis.11 Mastitis should be managed with breastfeeding frequently or expressing milk from the affected breast in an effort to clear blocked ducts and reduce engorgement, complemented if necessary with the use of analgesics, hot compresses, and antibiotics.10

Although there have been numerous observational studies of mastitis in developed countries, very few published data are available from developing countries. A prospective cohort study from China12 reported a 6.3% (n = 670) 6-month incidence of mastitis, of which half of the cases occurred in the first 4 weeks postpartum. There have been no published cohort studies of the incidence of mastitis in South Asian countries.

Although breastfeeding is universally practiced in Nepal, continuation of exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months remains low (29%).13 Support for postpartum breastfeeding problems from trained health personnel is rarely available.14 The existing maternal care programs in Nepal focus on safe childbirth, as well as the provision of skilled birth attendants.15,16 The management of lactation problems is not a part of routine postpartum assessment and care.15 Lactation problems experienced by Nepalese mothers have not been reported previously. The objective of this study, therefore, was to report the incidence, determinants, and management of mastitis in the first month postpartum, as well as its association with breastfeeding outcomes at 4 and 6 months postpartum in western Nepal. Findings from this study will be useful to inform and justify future postpartum lactation support programs.

Subjects and Methods

A prospective cohort study was conducted in the Rupandehi District of western Nepal during January–October 2014.17 The District benefits from a plain terrain with relatively good access to hospitals in urban areas, with rural health facilities (health posts and primary healthcare centers) in rural areas. In brief, we recruited 735 mothers (378 rural and 357 urban) from a total of 15 Village Development Committees in rural areas and 12 communities from urban areas that were randomly selected from a list of communities provided by the local public health office.17 Lists of eligible mothers were prepared in the selected areas with the help of local female community volunteers and health facilities. The required numbers of mothers were selected randomly from the lists. The number of mother–infant pairs recruited from each community was proportionate to population size based on the monthly target of expected numbers of infants <30 days of age.

Mothers who were local residents, had living infants, were within 1 month postpartum, and had a singleton child were recruited into the study. Mothers were excluded if they were seriously ill or if they were not a local resident of the selected communities. Participants were followed up during the fourth (90–120 days) and sixth (150–180 days) months postpartum. Information on infant feeding practices was collected at baseline and each follow-up visit. Trained female enumerators collected the data using structured questionnaires adapted from the Nepal Demographic and Health Survey18 and a published study on mastitis.6 The questionnaires were translated into the Nepali language and pretested before being used in the field. The baseline interviews were conducted in the first month (0–30 days) postpartum, and information on sociodemographic characteristics and lactation problems was collected at this time.

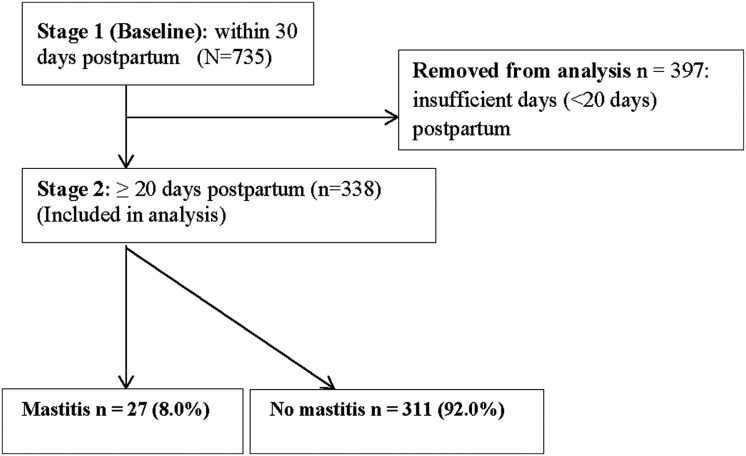

Variables

The response variable used in this study was the incidence of mastitis in the neonatal period, which was based on self-reported signs and symptoms. We defined mastitis as at least two breast symptoms (pain, redness or lump) and at least one of the “flu-like symptoms” (fever, shivering/chills, and headache) based on the definition used by Amir et al.8 The breastfeeding problems experienced during the neonatal period were recorded as “yes” or “no” responses to prompted questions. Information on mastitis used in this analysis was collected at the baseline interview. Mothers whose infants were in the age group 20–30 days were included for reporting the incidence of mastitis to ensure that most cases of mastitis in the neonatal period were included, and this provided us with a final sample size of 338 (Fig. 1). We compared the mothers excluded with those included in the analysis, and there were no differences in the major demographic characteristics between the two groups, including maternal age, education, type of delivery, and parity. We also collected information on the management of mastitis, the sources of advice, and advice received. Information on breastfeeding outcomes was collected from all mothers with and without mastitis during the fourth and sixth month postpartum interviews.

FIG. 1.

Flow chart of the cohort study.

The World Health Organization's breastfeeding definitions were used in this study.19 Exclusive breastfeeding was defined as “breast milk (including expressed milk or from a wet nurse), vitamin or mineral syrups, medicine and oral rehydration salt, and no other liquid or solid food items.” Predominant breastfeeding was defined as “breast milk (including milk expressed or from a wet nurse) as the predominant source of nourishment; including certain liquids (water and water-based drinks, fruit juice), ritual fluids and oral rehydration salt, drops or syrups (vitamins, minerals, medicines) and does not allow anything else (in particular, non-human milk, food-based fluids).” We used the “recall-since-birth” method to report exclusive breastfeeding and predominant breastfeeding and not the current breastfeeding status.20

The selection of independent variables was based on a literature review of plausible factors associated with lactation mastitis.6,8,9,12 Independent variables included in the study were maternal age (15–19, 20–29, and 30–45 years), maternal education (no education, primary to lower secondary [up to Grade 8], secondary [Grades 9–10], and higher [Grades 11–12 and university degree]), and place of delivery (health facility [public hospital, private hospital, clinic, health post, sub-health post, primary healthcare center, birthing centers] and home [home or on the way to health facility]). Other independent variables included were prelacteal feeding (yes or no), time of initiation of breastfeeding (within 1 hour or after 1 hour), mode of delivery (vaginal or cesarean), and birth weight (low birth weight [<2,500 g] and average or greater [≥2,500 g]).

Statistical analysis

Factors associated with mastitis were screened using the chi-squared test, and those factors significantly associated with the incidence of mastitis were further investigated using multivariable logistic regression,21 adjusting for the duration of exposure (days since childbirth) using the “off-set” term in Stata release 14 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX). This was deemed necessary in order to adjust for the unequal duration of exposure since childbirth to recruitment among the participants. The stepwise backward elimination method was performed in the logistic regression.

The association between mastitis and exclusive and predominant breastfeeding at 4 and 6 months was determined using multivariable logistic regression adjusting for other independent variables (maternal education, maternal age, place of residence, mode of delivery, birth weight, time of initiation of breastfeeding, and place of delivery) investigated in the study. We further examined the duration of exclusive breastfeeding using the Kaplan–Meier method. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata release 14 software and Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 20 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

The mean age of infants at recruitment was 26 days. Table 1 illustrates the characteristics of participants at baseline (n = 338). About a quarter (26.9%) of the mothers had no education, 47.0% were from poor families, 86.4% delivered in a health facility, and 13.6% delivered by cesarean section. All of the mothers were breastfeeding at recruitment, and 31.7% reported providing prelacteal feeds to their newborn infants.

Table 1.

Incidence of Mastitis by Participant Characteristics in Nepal in 2014 (n = 338)

| Characteristic | Frequency (%) (n = 338) | Mastitis (%) (n = 27) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years)b | 0.039 | ||

| 15–19 | 30 (8.8) | 6 (20.0) | |

| 20–29 | 252 (74.6) | 17 (6.7) | |

| 30–45 | 56 (16.6) | 4 (7.1) | |

| Maternal education | 0.006 | ||

| No education | 91 (26.9) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Primary to lower secondary | 122 (36.1) | 8 (6.6) | |

| Secondary | 55 (16.3) | 5 (9.1) | |

| Higher | 70 (20.7) | 12 (17.1) | |

| Place of residence | 0.344 | ||

| Rural | 192 (56.8) | 13 (6.8) | |

| Urban | 146 (43.2) | 14 (9.6) | |

| Place of delivery | NA | ||

| Home | 46 (13.6) | 2 (4.3) | |

| Health facility | 292 (86.4) | 25 (8.6) | |

| Mode of delivery | <0.001 | ||

| Vaginal | 292 (86.4) | 17 (5.8) | |

| Cesarean | 46 (13.6) | 10 (21.7) | |

| Time of initiation of first breastfeedingb | 0.798 | ||

| After 1 hour | 198 (58.8) | 17 (8.3) | |

| Within first hour | 133 (40.2) | 10 (7.5) | |

| Prelacteal feeding | 0.019 | ||

| No | 231 (68.3) | 13 (5.6%) | |

| Yes | 107 (31.7) | 14 (13.1) | |

| Birth weightb | NA | ||

| Low (<2,500 g) | 46 (14.8) | 1 (2.2) | |

| Average or greater (≥2,500 g) | 234 (85.2) | 23 (8.7) |

Values for p are obtained from the chi-squared test of association with mastitis.

Data missing for some participants.

NA, not applicable due to small sample size.

Table 2 presents the description of breastfeeding problems reported by mothers. A total of 27 (8.0%; 95% confidence interval, 5.1%, 10.8%) mothers reported having at least one episode of mastitis within the neonatal period (Table 2). In addition, 9.8% reported cracked nipples, and 8.9% reported a breast abscess. Findings from logistic regression after accounting for duration of exposure showed that those women who provided prelacteal feeds to their newborn infants (adjusted odds ratio = 2.76; 95% confidence interval, 1.03, 7.40) and who had delivered by cesarean section (adjusted odds ratio = 3.52; 95% confidence interval, 1.09, 11.42) had a higher likelihood of mastitis (Table 3).

Table 2.

Lactation Problems Within the First Month Postpartum in Nepal in 2014 (n = 338)

| Problem | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Cracked or sore nipple | 33 (9.8) |

| Breast abscess (wound) | 30 (8.9) |

| Mastitisa | 27 (8.0) |

| Red | 29 (8.6) |

| Pain | 95 (28.1) |

| Lump | 18 (5.3) |

| Fever | 57 (16.9) |

| Shivering/chills | 47 (13.9) |

| Headache/body ache | 92 (27.2) |

Signs and symptoms of mastitis. Mastitis was defined as at least two breast symptoms (pain, redness, or lump) and at least one of the flu-like symptoms (fever, shivering/chills, or headache).

Table 3.

Factors Associated with Mastitis in Nepal in 2014

| Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Factor | Crude | Adjusted |

| Prelacteal feeding | p = 0.02 | p = 0.05 |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 2.08 (0.90, 4.78) | 2.76 (1.03, 7.40) |

| Mode of delivery | p = 0.003 | p = 0.04 |

| Vaginal | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Cesarean | 4.01 (1.58, 10.18) | 3.52 (1.09, 11.42) |

Variables excluded were maternal age and maternal education. Time of interview was used as the measure of exposure.

Mothers were mainly advised to express and empty their breasts (29.6%), to continue breastfeeding as usual (25.6%), and to breastfeed more frequently than before (18.5%), showing a strong support toward avoiding milk stasis (Table 4). Only one mother was advised to stop breastfeeding, although three (11.1%) reported stopping breastfeeding due to mastitis. Table 4 also presents practices used by mothers to manage mastitis (n = 27), with the most common being breastfeeding frequently from the affected breast (55.6%), followed by expressing breastmilk (40.7%), and the use of pain killers (22.2%). Doctors and other health workers (35.7%), mothers/mothers-in-law (35.7%), and other family members and relatives (35.7%) were the major sources of advice.

Table 4.

Advice Received and Methods Used by Mothers in Nepal in 2014 to Manage Mastitis (n = 27)

| Response | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Advice receiveda | |

| Express breastmilk and empty breasts | 8 (29.6) |

| Continue breastfeeding as usual | 7 (25.6) |

| Breastfeeding more frequently than before | 5 (18.5) |

| Take medicine | 3 (11.1) |

| Use home medicines | 2 (7.4) |

| Stop breastfeeding | 1 (3.7) |

| Methodsa | |

| Breastfeeding frequently from affected breast | 15 (55.6) |

| Expressing breastmilk | 11 (40.7) |

| Use of pain killers | 6 (22.2) |

| Massaging affected breast before breastfeeding | 6 (22.2) |

| Hot compress before and after breastfeeding | 5 (18.5) |

| Stopped breastfeeding | 3 (11.1) |

| Started weaning | 3 (11.1) |

| Use of antibioticsb | 1 (3.7) |

Multiple responses allowed.

Patients can buy antibiotics without any prescription in Nepal.

Of the 338 mothers, all were breastfeeding at baseline, 326 (99.4%; n = 328) were still breastfeeding in the fourth month, and 324 (99.0%; n = 327) still were in the sixth month. Although 220 (65.1%; n = 338) of the mothers breastfed exclusively at baseline, this proportion was reduced to 124 (37.8%; n = 328) in the fourth month and to 24 (7.3%; n = 327) in the sixth month. Three-quarters (n = 254; 75.1%) of the mothers were breastfeeding predominantly at baseline, followed by 190 (57.9%) in the fourth month and 45 (13.8%) in the sixth month. The median duration of exclusive breastfeeding (n = 338) was 102 days (95% confidence interval, 95.12, 108.84 days) with no significant difference (log-rank p = 0.358) between the mothers with and without mastitis. Table 5 gives the breastfeeding outcomes of the groups of mothers with and without mastitis and shows that the exclusive breastfeeding and predominant breastfeeding rates did not differ significantly among those with and without mastitis. Multivariable logistic regression also confirmed that there was no significant difference in breastfeeding rates at 4 months (Table 5).

Table 5.

Association Between Mastitis and Breastfeeding Outcomes in Nepal in 2014

| Breastfeeding outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breastfeeding practices | Yes (%) | No (%) | Adjusted odds ratio(95% confidence interval)a | p value |

| Exclusive breastfeeding in | ||||

| 4th month (n = 328) | ||||

| Mastitis (n = 27) | 6 (4.8) | 21 (10.3) | 0.47 (0.15, 1.50) | 0.204 |

| No mastitis (n = 301) | 118 (95.2) | 183 (89.7) | 1.00 | |

| 6th month (n = 327) | ||||

| Mastitis (n = 27) | 0 (0.0) | 27 (8.9) | NA | |

| No mastitis (n = 300) | 24 (100.0) | 276 (91.1) | ||

| Predominant breastfeeding in | ||||

| 4th month (n = 328) | ||||

| Mastitis (n = 27) | 11 (5.8) | 16 (11.6) | 0.66 (0.25, 1.75) | 0.399 |

| No mastitis (n = 301) | 179 (94.2) | 122 (88.4) | 1.00 | |

| 6th month (n = 327) | ||||

| Mastitis (n = 27) | 2 (4.4) | 25 (8.9) | NA | |

| No mastitis (n = 300) | 43 (95.6) | 257 (91.1) | ||

| Any breastfeeding in | ||||

| 4th month (n = 328) | ||||

| Mastitis (n = 27) | 27 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | NA | |

| No mastitis (n = 301) | 299 (91.7) | 2 (100.0) | ||

| 6th month (n = 327) | ||||

| Mastitis (n = 27) | 26 (8.0) | 1 (33.3) | NA | |

| No mastitis (n = 300) | 298 (92.0) | 2 (66.7) | ||

Each row presents the result from logistic regression.

Adjusted for maternal education, maternal age, place of residence, mode of delivery, birth weight, time of initiation of breastfeeding, and place of delivery.

NA, not applicable due to small numbers.

Discussion

We found that 8.0% of mothers reported having an episode of mastitis within the first 30 days postpartum in western Nepal. Published studies from Scotland (9.5%)6 and Australia (9.1%)8 reported comparable incidence of mastitis when the results from those studies are confined to the first 4 weeks of the postpartum period. Lactation mastitis is relatively common in the first few weeks when breastfeeding is being established and declines thereafter.3 In our setting, despite a universal practice of breastfeeding, the current rate of lactation mastitis is comparable to those in developed countries with lower breastfeeding rates, and it justifies the need for lactation support during the postpartum period.

However, two major points must be considered when interpreting the incidence of mastitis and comparing rates between studies. First, the reporting periods may differ among the cohort studies, which might explain some of the variations in the reported incidence.22 For instance, Vogel et al.4 followed a cohort of New Zealand for 12 months and reported that 15.7% of cases experienced their first instance of mastitis when their infant was older than 6 months. Second, we adapted the definition used by Amir et al.8 of at least two breast symptoms (pain, redness, or lump) and at least one of the “flu-like symptoms” (fever, shivering/chills, or headache), whereas studies in China12 and Glasgow6 have used a slightly different definition. Although the majority of earlier studies used self-reported symptoms to define mastitis, Foxman et al.7 reported the incidence of provider-diagnosed mastitis, which might account for the relatively low incidence of mastitis (9.5%) reported in their study. A study of Scottish women reported that roughly one-third of women self-managed their mastitis and did not seek health professional care for their condition and hence would not have been considered to be cases if a provider-diagnosed definition had been applied.6

Although Fetherston2 reported that 18% of the mothers cited mastitis as a reason for cessation of breastfeeding, Amir et al.8 did not find any significant difference in the duration of breastfeeding; both of these studies were from Australia. In contrast, other groups4,6 have found that mothers with mastitis tended to breastfeed longer than those who did not experience mastitis. In our study, there was no significant difference in the duration of exclusive breastfeeding between mothers who did and did not experience mastitis, which is an important finding. In Nepal breastfeeding is deemed the best practice23 and universally practiced. The traditional cultural practice of universal breastfeeding, as well as community and family encouragement and support to continue breastfeeding, could have been major factors to continue breastfeeding among the mothers who had mastitis. Our finding demonstrates that the adverse effect of mastitis on breastfeeding practices can be minimized if mothers are encouraged and supported to continue breastfeeding.

This is the first study to report on the methods used by women in Nepal to manage mastitis and the types of professional and lay advice they receive. The World Health Organization recommends emptying the breast by frequent breastfeeding or expressing,10 and our study found that most of the mothers had received advice to this effect, which they were following. However, a small proportion of women had stopped breastfeeding as a result of their mastitis, or had been told to do so, and future lactation promotion programs in Nepal should discourage this practice.

It should be noted that when mothers had mastitis, female elders such as mothers-in-law were as an important a source of advice as health workers. In Nepal, female elders are key to decision-making related to reproductive health24 and breastfeeding,25 and this appears to remain the case when mothers have mastitis. Postpartum mothers in Nepal are kept in isolation and are not allowed to leave the home for the first few weeks of childbirth,16 which is when mastitis occurs most frequently.12 During this period female elders are the most accessible source of advice and support; they should be a target group for lactation support programs.

We found that mothers who reported providing prelacteal feeds to their newborn infants and who had delivered by cesarean section were more at risk of having an episode of mastitis. These factors are linked to delayed initiation of breastfeeding and, therefore, increased the risk of milk stasis, which is a major risk factor for mastitis.10 Mothers who undergo cesarean section may still be under the effect of anesthesia for many hours after surgery and are not able to move out of bed. In such circumstances, unless their infant is brought to their bedside, their breasts are not emptied regularly, thereby increasing the risk of milk stasis and breast engorgement.10 Future lactation support programs should focus on these groups to prevent mastitis.

Our study is the first study reporting the incidence of mastitis from the traditional breastfeeding communities of South Asia. The methodology used in this study reduces the likelihood of recall bias as the information on mastitis was collected within 30 days postpartum. The major limitations of this study resulted from the pragmatic conduct of the study and with it being a community-based study. As a result it was not possible to conduct the baseline and follow-up surveys at set time points in days since childbirth, and we had to use a time period to allow reasonable flexibility. Limiting the analysis population to those women with infants 20–30 days of age at baseline resulted in a relatively small sample. Although the incidence of mastitis is based on self-reporting of symptoms, and as such might be considered a limitation, it can be argued that provider diagnosis of mastitis underestimates the true incidence of mastitis as sizeable proportions of women self-manage their condition. Moreover, collecting data on mastitis within 30 days postpartum might not capture cases that would occur after that period, leading to under-reporting of the incidence. A small number of observations in certain subcategories, such as in cesarean delivery, resulted in wide confidence intervals. Future studies with a larger sample of infants recruited within the first few days of birth and with information on mastitis routinely collected at set time points for at least the first 6 months of life would provide more rigorous information.

Nevertheless, despite these limitations our study has reported an incidence of mastitis in the first month postpartum that is remarkably consistent with the findings of studies in developed countries, suggesting that this is a relatively common condition even in societies that promote traditional breastfeeding practices. To our knowledge it is the first study to report the incidence of mastitis in South Asian countries and has identified vulnerable groups that need further support to prevent mastitis. Mothers with mastitis should receive supportive counseling on proper attachment positions, be instructed how to effectively remove breastmilk via frequent breastfeeding and breastfeeding on demand, and if symptoms persist be provided with antibiotic therapy.10 The current postpartum care guidelines in Nepal should include the management of mastitis and lactation support.

Conclusions

Our study reported that roughly one in 10 mothers experienced mastitis in the first month postpartum. Mastitis did not have a significant adverse effect on the duration of exclusive breastfeeding and the rates of predominant and any breastfeeding rates at 4 and 6 months. Nevertheless, mastitis is a painful but preventable condition, and health workers should provide support to mothers to prevent and manage mastitis appropriately. The maternal health programs of Nepal should include screening for and management of lactation problems during the postpartum period as a routine maternal care practice.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Schwartz K, D'Arcy HJ, Gillespie B, et al. Factors associated with weaning in the first 3 months postpartum. J Fam Pract 2002;51:439–444 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fetherston C. Characteristics of lactation mastitis in a Western Australian cohort. Breastfeed Rev 1997;5:5–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binns C, Scott JA. Breastfeeding: Reasons for starting, reasons for stopping and problems along the way. Breastfeed Rev 2002;10:13–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogel A, Hutchison BL, Mitchell EA. Mastitis in the first year postpartum. Birth 1999;26:218–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinlay JR, O'Connell DL, Kinlay S. Risk factors for mastitis in breastfeeding women: Results of a prospective cohort study. Aust N Z J Public Health 2001;25:115–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott JA, Robertson M, Fitzpatrick J, et al. Occurrence of lactational mastitis and medical management: A prospective cohort study in Glasgow. Int Breastfeed J 2008;3:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foxman B, D'Arcy H, Gillespie B, et al. Lactation mastitis: Occurrence and medical management among 946 breastfeeding women in the United States. Am J Epidemiol 2002;155:103–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amir LH, Forster DA, Lumley J, et al. A descriptive study of mastitis in Australian breastfeeding women: Incidence and determinants. BMC Public Health 2007;7:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fetherston C. Risk factors for lactation mastitis. J Hum Lact 1998;14:101–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Mastitis: Causes and Management. World Health Organization, Geneva, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbosa-Cesnik C, Schwartz K, Foxman B. Lactation mastitis. JAMA 2003;289:1609–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang L, Lee AH, Qiu L, et al. Mastitis in Chinese breastfeeding mothers: A prospective cohort study. Breastfeed Med 2013;9:35–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karkee R, Lee A, Khanal V, et al. A community-based prospective cohort study of exclusive breastfeeding in central Nepal. BMC Public Health 2014;14:927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karkee R, Lee AH, Khanal V, et al. Infant feeding information, attitudes and practices: A longitudinal survey in central Nepal. Int Breastfeed J 2014;9:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Family Health Division, Ministry of Health and Population. National Safe Motherhood and Newborn Health Long Term Plan (2006–2017). Family Health Division and Ministry of Health and Population, Kathmandu, Nepal, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khanal V, Adhikari M, Karkee R, Gavidia T. Factors associated with the utilisation of postnatal care services among the mothers of Nepal: Analysis of Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2011. BMC Womens Health 2014;14:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khanal V, Scott JA, Lee AH, et al. Factors associated with early initiation of breastfeeding in Western Nepal. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015;12:9562–9574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ministry of Health and Population, New ERA ICF International Inc. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Ministry of Health and Population, Kathmandu, Nepal; New ERA and ICF International, Calverton, MD, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices: Conclusions of a Consensus Meeting Held 6–8 November 2007 in Washington DC, USA. World Health Organization, Geneva, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aarts C, Kylberg E, Hörnell A, et al. How exclusive is exclusive breastfeeding? A comparison of data since birth with current status data. Int J Epidemiol 2000;29:1041–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun GW, Shook TL, Kay GL. Inappropriate use of bivariable analysis to screen risk factors for use in multivariable analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49:907–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kvist LJ. Re-examination of old truths: Replication of a study to measure the incidence of lactational mastitis in breastfeeding women. Int Breastfeed J 2013;8:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paneru S. Breast feeding in Nepal: Religious and cultural beliefs. Contrib Nepal Stud 1981;8:43–54 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simkhada B, Porter MA, van Teijlingen ER. The role of mothers-in-law in antenatal care decision-making in Nepal: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010;10:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masvie H. The role of Tamang mothers-in-law in promoting breast feeding in Makwanpur District, Nepal. Midwifery 2006;22:23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]