Abstract

Background and purpose

In a previous registry report, short-term implant survival of hip resurfacing arthroplasty (HRA) in Finland was found to be comparable to that of total hip arthroplasty (THA). Since then, it has become evident that adverse reactions to metal debris (ARMDs) may also be associated with HRA, not only with large-diameter head metal-on-metal THA. The aim of the study was to assess medium- to long-term survivorship of HRA based on the Finnish Arthroplasty Register (FAR).

Patients and methods

5,068 HRAs performed during the period 2001–2013 in Finland were included. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to calculate survival probabilities and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Cox multiple regression, with adjustment for age, sex, diagnosis, femoral head size, and hospital volume was used to analyze implant survival of HRA devices with revision for any reason as endpoint. The reference group consisted of 6,485 uncemented Vision/Bimetric and ABG II THAs performed in Finland over the same time period.

Results

The 8-year survival, with any revision as an endpoint, was 93% (CI: 92–94) for Birmingham Hip Resurfacing (BHR), 86% (CI: 78–94) for Corin, 91% (CI: 89–94) for ReCap, 92% (CI: 89–96) for Durom, and was 72% (CI: 69–76) for the Articular Surface Replacement (ASR). The 10-year survival, with any revision as an endpoint, for reference THAs was 92% (CI: 91–92) and for all HRAs it was 86% (CI: 84–87%). Female HRA patients had about twice the revision risk of male patients. ASR had an inferior outcome: the revision risk was 4-fold higher than for BHR, the reference implant.

Interpretation

The 10-year implant survival of HRAs is 86% in Finland. According to new recommendations from NICE (The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence), an HRA/THA should have a revision rate of 5% or less at 10 years. None of the HRAs studied achieved this goal.

Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty (HRA) has theoretical advantages over total hip arthroplasty (THA) for younger patients: bone stock preservation on the femoral side, more physiological loading of the proximal femur, and a low risk of dislocation due to the large head. It has, however, become evident that adverse reactions to metal debris (ARMDs) may often be associated with HRA also, not only with large-diameter head metal-on-metal THA. The Articular Surface Replacement HRA (ASR; DePuy, Leeds, UK) and the Durom HRA (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN) have been recalled from the market due to a high prevalence of ARMDs and a high early revision rate. Other HRA devices have had variable success. The survival rate of the Birmingham Hip Resurfacing (BHR) (Smith and Nephew, Warwick, UK) has been higher than that of all other HRA devices, according to reports from national registries (AOANJRR, NJR, NZJR).

According to a previous report from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register (FAR) with data from 2001 to 2009 (Seppänen et al. 2012), 8-year implant survival of HRA in Finland was comparable to that of THA. Lately, however, a prevalence of ARMD of no less than 7% in male patients and 9% in female patients has been reported for BHR at 10 years (Reito et al. 2014). Disconcertingly, Bisschop et al. (2013) reported a 28% prevalence of CT-verified pseudotumors for BHR by 3 years. Junnila et al. (2015) reported 17 ARMD cases in 42 BHR hips diagnosed with MRI and blood ion measurements, 7 years after the hip arthroplasty; 4 hips had been revised.

It has recently been stated that the routine use of HRA may not be justified (Dunbar et al. 2014). In addition, resurfacing components are more costly and do not provide any additional benefit over THA, even for younger patients (Jameson et al. 2015). As early as May 2012, the Finnish Arthroplasty Society recommended that MoM HRAs should no longer be used (FAA 2012). A nationwide screening of all MoM HRA and THA patients was started. The screening involved patient-reported outcome measures (Oxford hip score), blood chromium and cobalt ion measurements, and radiography. This report is an update on 8- to 10-year survivorship of HRA with FAR data extending from 2001 to 2013.

Patients and methods

The FAR has collected information on total hip replacements since 1980 (Paavolainen et al. 1991). Orthopedic units are obliged to provide the Finnish National Institute for Health and Welfare with information essential for maintenance of the register. Dates of death and dates of individuals leaving the country are obtained from Statistics Finland. Data capture of the Finnish Arthroplasty Register is high when compared to the Discharge Register (www.thl.fi/far). An English translation of the FAR notification form has been published (Puolakka et al. 2001). From May 19, 2014, all hip and knee data have been recorded electronically based on bar-code reading.

6 HRA designs used in at least 100 operations during the study period 2001–2013 were included (Table 1). There were 5,068 HRAs altogether, of which 4,474 (88%) were performed for primary osteoarthritis, 323 (6.4%) for secondary osteoarthritis, 47 (0.9%) for rheumatoid arthritis, 26 (0.5%) for other inflammatory arthritis, 68 (1.3%) for congenital dislocation of the hip, and 130 (2.6%) for other indications. The reference group consisted of 6,485 uncemented Vision/Bimetric THAs (Biomet, Warsaw, IN) and ABG II THAs (Stryker, Mahwah, NJ) THAs performed in the same time period. Demographic data are presented in Table 2 and the indications for revision are given in Table 3.

Table 1.

HRA designs used in ≥100 operations during the period 2001–2013 in Finland

| Implant design | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| BHR | 2,141 | 42 |

| ASR | 1,051 | 21 |

| ReCap | 846 | 17 |

| Conserve Plus | 579 | 11 |

| Durom | 350 | 7 |

| Cormet | 101 | 2 |

| Total | 5,068 | 100 |

Table 2.

Demographic data for hip resurfacing arthroplasty (HRA) and total hip arthroplasty (THA), which was used for reference

| HRA | reference THA | |

|---|---|---|

| n = 5,068 | n = 6,485 | |

| Mean follow-up (range), years | 6.8 (0.0–12.7) | 7.9 (0.0–13.0) |

| Median follow-up, years | 7.0 | 8.8 |

| Mean age (range), years | 54 (9–86) | 64 (15–97) |

| Males, % | 67 | 46 |

| Implanting period | 2001–2013 | 2001–2013 |

| No. of hospitals | 49 | 65 |

| Diagnosis, % primary osteoarthritis | 88 | 84 |

Table 3.

Reasons for revision. Values are n (%)

| HRA | reference THA | |

|---|---|---|

| Reason for revision | n = 5,068 | n = 6,485 |

| Aseptic loosening of | ||

| both components | 215 (40) | 96 (19) |

| the cup | 53 (10) | 22 (4) |

| the stem | 18 (3) | 23 (4) |

| Infection | 17 (3) | 33 (7) |

| Dislocation | 6 (1) | 132 (26) |

| Malposition | 45 (8) | 49 (10) |

| Fracture | 49 (9) | 85 (17) |

| Implant breakage | 3 (1) | 18 (4) |

| Other reason a | 131 (24) | 49 (10) |

| All | 537 | 507 |

Including ARMD (adverse reaction to metal debris).

Statistics

The survival of the HRA devices and the reference arthroplasties was assessed by Kaplan-Meier analysis. The Cox multiple regression model was used to assess differences in revision rates of the HRA devices and to adjust for any confounding factors. Revisions were linked to the primary operation through the personal identification number. The survival endpoint was defined as revision, when either 1 of the components or the entire implant was removed or exchanged. Revision for any reason served as an endpoint. Kaplan-Meier survival data were used to construct the survival probabilities of implants, with 95% confidence interval (CI). HRA and THA devices of patients who died or left Finland during the follow-up period were regarded as having survived until that point. The factors studied with the Cox model were HRA device, age group, sex, diagnosis, femoral head size (classified as ≤44 mm, 45–49 mm, 50–54 mm, and ≥55 mm) and hospital production volume of arthroplasties (≥ 100 or <100 procedures).

The Cox analysis between the whole HRA group and the reference THA group showed that these factors were not useful. The sizes of the femoral heads of the reference THA group were smaller than those of the HRA group. Diagnosis and hospital volume had no effect and were censored. Female sex had no effect in the reference THA group, but the effect in the HRA group was strong and negative. Several age groups were tested, but age did not emerge as a significant factor in either group. After careful analysis, we decided to compare the HRA group and the reference group without consideration of these potentially confounding factors.

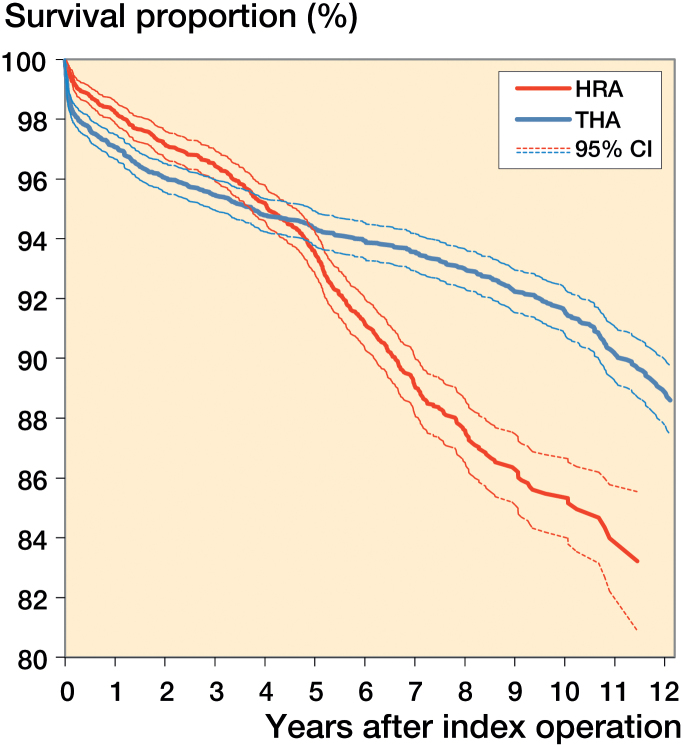

The proportional-hazards assumption of the Cox models was checked by inspecting the corresponding log-log graphs. For Cox analyses comparing the HRA brands and the reference THA group, we divided the total follow-up time into 3 periods (first year, second and third year combined, and fourth year onwards), because the proportional-hazards assumption was not fulfilled for the total follow-up, as can be seen from Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival of HRA and uncemented reference THA.

Death of the patient and revision are competing risk in registry studies. We therefore repeated the analyses without the patients who died during follow-up (3.2% in the HRA group and 14% in the THA group) (Appendix 1, see Supplementary data). Furthermore, we performed competing risk analyses using Stata 14 statistical software (Appendix 2, see Supplementary data).

Inclusion of bilateral cases in a survival analysis violates the basic assumption that all cases are independent. However, several reports have shown that the effect of including bilateral cases in studies of hip and knee joint prosthesis survival, as done in our study, is negligible (Lie et al. 2004, Robertsson and Ranstam 2003). The Wald test was used to test the estimated hazard ratios. Differences between groups were considered to be statistically significant if the p-values were less than 0.05 in a 2-tailed test.

Results

67% of the HRA patients were male, and the mean age of the study population was 54 (9–86) years. Primary osteoarthritis was the most common diagnosis (88%) (Table 2). The main reason for revision of HRAs was aseptic loosening of both components (40%), whereas THAs were most often revised due to dislocation (26%). Unspecified reasons for revision ("other") were recorded for 24% of the HRA revisions and for 10% of the THA revisions (Table 3).

The 10-year Kaplan-Meier survival was 86% (CI: 84–87) for the HRA group and 92% (CI: 91–92) for the reference THA group (Figure 1 and Table 4).

Table 4.

Survival of HRA devices and the reference THA group. Endpoint was defined as revision of any component for any reason. Survival rates according to Kaplan-Meier analysis

| n | Follow-up, years | At risk, | 5-year survival | At risk, | 8-year survival | At risk, | 10-year survival | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean (range) | 5 years | (95% CI) | 8 years | (95% CI) | 10 years | (95% CI) | ||

| BHR | 2,141 | 7.6 (0.0–12.7) | 1,703 | 96 (95–97) | 1,146 | 93 (92–94) | 698 | 91 (89–92) |

| ASR | 1,051 | 6.5 (0.0–9.8) | 864 | 88 (86–90) | 253 | 72 (69–76) | 0 | – |

| ReCap | 846 | 5.5 (0.0–9.7) | 546 | 94 (93–96) | 183 | 91 (89–94) | 0 | – |

| Conserve Plus | 579 | 5.3 (0.0–8.7) | 428 | 95 (93–97) | 6 | – | 0 | – |

| Durom | 350 | 6.9 (0.0–9.1) | 326 | 95 (93–98) | 103 | 92 (89–96) | 0 | – |

| Corin (Cormet) | 101 | 9.1 (0.7–11.6) | 95 | 94 (89–99) | 72 | 92 (87–97) | 46 | 86 (78–94) |

| All HRAs | 5,086 | 6.8 (0.0–12.7) | 3,848 | 94 (93–94) | 1,724 | 88 (87–89) | 701 | 86 (84–87) |

| Reference THAs | 6,485 | 7.9 (0.0–13.0) | 4,801 | 94 (94–95) | 3,711 | 93 (92–94) | 2,402 | 92 (91–92) |

The ASR was associated with a higher risk of revision than the BHR (revision ratio (RR) = 4.0, CI: 3.2–4.9; p < 0.001) (Table 5). The CIs for the BHR, Durom, ReCap, Converse Plus, and Corin designs overlapped considerably, and the analysis does not permit ranking among them.

Table 5.

Revision ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for HRA devices compared to BHR. Data are based on a Cox regression model including implant design, sex, and femoral head diameter (categorized as ≤44 mm, 45–49 mm, 50–54 mm, and ≥55 mm). Age group, hospital volume (≥ 100 or <100 procedures) and diagnosis had no significant effect on adjustment (data not shown)

| RR | 95% CI of RR | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BHR (reference) | 1.00 | ||

| Cormet | 1.05 | 0.59–1.87 | 0.9 |

| ASR | 3.96 | 3.20–4.91 | < 0.001 |

| ReCap | 1.21 | 0.88–1.67 | 0.2 |

| Durom | 1.02 | 0.65–1.58 | 0.9 |

| Conserve Plus | 1.30 | 0.90–1.88 | 0.2 |

| Female (male reference) | 2.12 | 1.66–2.70 | < 0.001 |

| Femoral head diameter, mm | |||

| < 44 (reference) | 1.00 | ||

| 45–49 | 0.70 | 0.54–0.92 | 0.01 |

| 50–54 | 0.61 | 0.44–0.85 | 0.003 |

| ≥ 55 | 0.46 | 0.27–0.77 | 0.003 |

Female patients had about twice the revision risk of male patients (RR =2.1, CI: 1.7–2.7; p < 0.001). A femoral head diameter of less than 44 mm was independently associated with a higher revision risk (Table 5).

BHR and ASR were associated with a lower revision risk than the reference THA during the first postoperative year. During the second and third postoperative years, ASR was associated with a higher revision risk than the reference THA. During follow-up from the fourth postoperative year onwards, BHR, Cormet, ASR, ReCap, and Converse Plus were associated with a higher risk of revision than the reference THA (Table 6).

Table 6.

Revision ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in 6 HRA devices compared to the uncemented reference THA. Data are based on a Cox regression model at different follow-up time intervals (the first year, the second and third years, and from the fourth year onwards)

| Follow-up interval: 1st year |

Follow-up interval: 2nd and 3rd year |

Follow-up: from 4th year onwards |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI for RR | p-value | RR | 95% CI for RR | p-value | RR | 95% CI for RR | p-value | |

| Reference THA | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| BHR | 0.48 | 0.32–0.70 | 0.0002 | 0.83 | 0.54–1.26 | 0.4 | 1.66 | 1.31–2.11 | < 0.001 |

| Cormet | 0.67 | 0.17–2.70 | 0.6 | 1.84 | 0.58–5.81 | 0.3 | 2.06 | 1.02–4.18 | 0.04 |

| ASR | 0.58 | 0.36–0.94 | 0.03 | 1.85 | 1.24–2.77 | 0.003 | 9.18 | 7.44–11.31 | < 0.001 |

| ReCap | 0.64 | 0.38–1.07 | 0.09 | 0.82 | 0.44–1.53 | 0.5 | 2.30 | 1.55–3.42 | < 0.001 |

| Durom | 0.58 | 0.26–1.31 | 0.2 | 1.44 | 0.70–2.95 | 0.3 | 1.15 | 0.59–2.25 | 0.7 |

| Conserve Plus | 1.00 | 0.61–1.64 | 1.0 | 0.78 | 0.36–1.68 | 0.5 | 1.78 | 1.03–3.08 | 0.04 |

The revision ratios at different follow-up time intervals for 6 HRA devices compared to uncemented reference THA—and with dead patients excluded—are presented in Appendix 1. The RRs from the fourth postoperative year onwards for 6 HRA devices compared to uncemented reference THA, and with death as competing risk, are presented in Appendix 2. Revision rate of all 6 HRA devices is increased from the fourth year onwards (Appendices, see Supplementary data).

Discussion

The 10-year implant survival of HRAs is 86% in Finland. The 10-year survival of the BHR in Finland is similar to that in England and Wales (91%). According to the current NICE recommendations, the revision rate of HRAs/THAs should be no higher than 5% by 10 years. None of the HRAs in this study achieved this goal.

The cumulative rate of revision of all HRAs by 10 years in Australia was 9.8%, and that of conventional THAs was 6.8% (AOANJRR). The cumulative rate of revision of all HRAs by 10 years in England and Wales (NJR) was 13%, and that of uncemented THAs was 7.7%. Our data support these findings: the overall long-term survival of conventional THAs is higher than that of HRAs. Lately, it has been stated, based on the NJR data, that there is no advantage in using resurfacing implants over THA, even in young patients (Jameson et al. 2015). In a previous report based on data from 2001–2009 (Seppänen et al. 2012), we concluded that HRA had comparable 4- to 8-year survivorship to that of THA at the national level. It is now evident that this conclusion was not valid in 8- to 10-year follow-up.

The 10-year cumulative rate of revision of the BHR is 6.9% in Australia (AOANJRR) and 9.0% in England and Wales (NJR). Our registry results on BHR are similar. Excellent implant survival results have been published for the BHR based on data from single centers. 10-year survival rates as high as 97%, 15-year survival rates of 96% (Daniel et al. 2014), and 10-year survival rates of 96% (Matharu et al. 2013) have been reported by the design center. An overall 13-year survival rate of 92% was reported for the BHR by van der Straeten et al. (2013) based on independent single-center data. The 10-year overall survival rates based on independent single centers have varied between 87% and 95% (Coulter et al. 2012, Holland et al. 2012, Murray et al. 2012, Reito et al. 2014). However, survival rates have constantly been worse for female patients, with 10-year survival rates of no more than 67% for women in younger age groups (Murray et al. 2012).

There has been concern about local adverse tissue reactions associated with the use of the BHR, as with other HRA devices. An ARMD prevalence of 6.9% in male patients and 8.8% in female patients has been reported for the BHR (Reito et al. 2014). Bisschop et al. (2013) reported a 28% prevalence of CT-verified pseudotumors in BHR patients by 3 years. In the current study, the revision risk for BHR was similar to that for other HRA devices except ASR. The revision risk for the BHR compared to uncemented THAs increases from the fourth postoperative year onward. The survival rate of BHRs beyond 10 years may deteriorate further compared to conventional THAs due to revisions indicated by ARMD.

The 7-year cumulative rate of revision of the ASR was 24% in Australia (AOANJRR) and the 10-year rate was 30% in England and Wales (NJR). These results are in line with ours. ASR was recalled by the manufacturer in September, 2010.

An 8-year implant survival of 96% with revision for any reason as endpoint was reported from single-center data by Vendittoli et al. (2013) for the Durom HRA. This extraordinary finding has not been verified in population-based registry studies. The 10-year cumulative rate of revision of the Durom was 10% in Australia (AOANJRR) and 9.4% in England and Wales (NJR). These data are in accordance with our results (8% at 8 years). Durom was recalled by the manufacturer 2008 due to high early revision rates.

An 11-year implant survival of 93% with revision for any reason as endpoint was reported from single-center data by Gross et al. (2012) for the Corin Cormet HRA. The cumulative revision rate for adverse wear failure was 1% (Gross and Liu 2013). The 10-year cumulative rate of revision of the Corin Cormet HRA was 19% in both Australia (AOANJRR) and England and Wales (NJR). Our results (14% at 10 years) are in accordance with these population-based findings.

According to single-center data, the implant survival rate of the ReCap HRA is 94% over 6 years (van der Weegen et al. 2012), 96% over 7 years (Gross and Liu 2012), and 100% over 7 years (Borgwardt et al. 2015). The 7-year cumulative percent probability of revision of the ReCap was 12% in Australia (AOANJRR) and 9% in England and Wales (NJR). Again, our results (9% at 8 years) are in accordance with previous population-based findings.

5-year survival rates of 98% (Amstutz et al. 2007) and 95% (Zylberberg et al. 2015) have been reported for the Conserve Plus HRA, based on single-center data. The 10-year survival rate of the Conserve Plus cup was 98% with aseptic loosening as the endpoint (Hulst et al. 2011) and 89% for the Converse Plus HRA with revision for any reason as endpoint (Amstutz et al. 2010). The 10-year cumulative rate of revision of the Conserve Plus was 14% in England and Wales (NJR). In Finland, the Conserve Plus HRA is not in common use and follow-up times are short, but we did find a 5-year survival rate for the Converse Plus of 95%, which is comparable to that of other HRA devices.

In the current report, as well as in the previous one, aseptic loosening was the most common reason for revision—53% and 51%, respectively (Seppänen et al. 2012). The most common reason for HRA revision in Australia has been loosening/lysis (33%), followed by metal-related pathology (24%), and fracture (21%) (AOANJRR). In England and Wales, the most common reason for HRA revision was pain, followed by aseptic loosening and other indications (NJR). The variation in indications for revisions between registries indicates that the definitions of the indications are ambiguous. Pain only or ARMD were not coded as reasons for revision in the previous pre-registry notification form of the FAR. Revisions performed for ARMD were coded as performed for "other reason". There were 131 HRA revisions (24% of all revisions) performed for "other reason" in the current study, compared to 8% in the previous report (Seppänen et al. 2012). These data have been available after the reformation of the registry on May 19, 2014.

The revision rate in women has reportedly been about twice that in men (AOANJRR, NJR). However, based on data from the Australian registry, adjustment for femoral head size eliminates female sex as an independent risk factor (Prosser et al. 2010). On the other hand, the NARA group found that femoral head diameter alone had no effect on the early revision rate (Johanson et al. 2010). We found that the HRA revision rate for women is twice as high as for men. We also found a higher risk of revision in the group with the smallest femoral head diameter. Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, a high hospital production volume was not associated with reduced risk of revision.

Since our study design was observational, it was vulnerable to omission of variables, which may have confounded our findings. Potentially important variables such as comorbidity and socioeconomic status were not available. In addition, important clinical information (such as radiological data, patient-reported outcome measure data, and data on blood metal ion concentrations) was not available.

Supplementary data

Appendix 1 and 2, are available on the website of Acta Orthopaedica (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 9663.

All the authors participated in the planning and design of the study and in interpretation of the results. The statistician PP performed statistical analyses in collaboration with the other authors. MS was responsible for writing the manuscript, and all the authors participated actively in preparation and revision of the article.

This study was supported by a Turku University Hospital EVO grant.

Australian Orthopaedic Association. National Joint Replacement Registry. Annual Report 2014.

References

- Amstutz H C, Ball S T, Le Duff M J, Dorey F J.. Resurfacing THA for patients younger than 50 year: results of 2- to 9-year followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007; 460: 159–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amstutz H C, Le Duff M J, Campbell P A, Gruen T A, Wisk L E.. Clinical and radiographic results of metal-on-metal hip resurfacing with a minimum ten-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92(16): 2663–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisschop R, Boomsma M F, Van Raay J J, Tiebosch A T, Maas M, Gerritsma C L.. High prevalence of pseudotumors in patients with Birmingham Hip Resurfacing prosthesis: a prospective cohort study of one hundred and twenty-nine patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 95(17): 1554–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgwardt A, Borgwardt L, Borgwardt L, Zerahn B, Fabricius S D, Ribel-Madsen S.. Clinical performance of the ASR and ReCap resurfacing implants – 7 years follow-up. J Arthroplasty 2015; 30(6): 993–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter G, Young D A, Dalziel R E, Shimmin A J.. Birmingham hip resurfacing at a mean of ten years: Results from an independent centre. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012; 94:315–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel J, Pradhan C, Ziaee H, Pynsent P B, McMinn D J W.. Results of Birmingham hip resurfacing at 12 to 15 years. Bone Joint J 2014; 96-B: 1298–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar M J, Prasad V, Weerts B, Richardson G.. Metal-on-metal hip surface replacement: the routine use is not justified. Bone Joint J 2014; 96-B (11 Supple A): 17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAS 2012. The Finnish Arthroplasty Society. http://www.suomenartroplastiayhdistys.fi [Google Scholar]

- Gross T P, Liu F.. Hip resurfacing with the Biomet Hybrid ReCap-Magnum system: 7-year results. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27(9): 1683–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross T P, Liu F.. Incidence of adverse wear reactions in hip resurfacing arthroplasty: a single surgeon series of 2,600 cases. Hip Int 2013; 23(3): 250–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross T P, Liu F, Webb L A.. Clinical outcome of the metal-on-metal hybrid Corin Cormet 2000 hip resurfacing system: an up to 11-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27(4): 533–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnish Arthroplasty Register. www.thl.fi/far

- Holland J P, Langton D J, Hashmi M.. Ten-year clinical, radiological and metal ion analysis of the birmingham hip resurfacing: From a single, non-designer surgeon. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012; 94: 471–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulst J B, Ball S T, Wu G, Le Duff M J, Woon R P, Amstutz H C.. Survivorship of Conserve® Plus monoblock metal-on-metal hip resurfacing sockets: radiographic midterm results of 580 patients. Orthop Clin North Am 2011; 42(2): 153–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameson S S, Mason J, Baker P, Gregg P J, Porter M, Deehan D J, Reed M R.. Have cementless and resurfacing components improved the medium-term results of hip replacement for patients under 60 years of age? Patient-reported outcome measures, implant survival, and costs in 24,709 patients. Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (1): 7–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanson P E, Fenstad A M, Furnes O, Garellick G, Havelin L I, Overgaard S, Pedersen A B, Kärrholm J.. Inferior outcome after hip resurfacing arthroplasty than after conventional arthroplasty. Evidence from the Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association (NARA) database, 1995 to 2007. Acta Orthop 2010; 81(5): 535–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junnila M, Seppänen M, Mokka J, Virolainen P, Pölönen T, Vahlberg T, Mattila K, Tuominen E K, Rantakokko J, Äärimaa V, Itälä A, Mäkelä K T.. Adverse reaction to metal debris after Birmingham hip resurfacing arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2015; 86(3): 345–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lie S A, Engesaeter L B, Havelin L I, Gjessing H K, Vollset S E.. Dependency issues in survival analyses of 55,782 primary hip replacements from 47,355 patients. Stat Med 2004; 30: 23 (20): 3227–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matharu G S, McBryde C W, Pynsent W B, Pynsent P B, Treacy R B.. The outcome of the Birmingham Hip Resurfacing in patients aged <50 years up to 14 years post-operatively. Bone Joint J 2013; 95-B: 1172–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray D W, Grammatopoulos G, Pandit H, Gundle R, Gill H S, McLardy-Smith P.. The ten-year survival of the Birmingham hip resurfacing: An independent series. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012; 94: 1180–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Joint Registry for England and Wales (NJR England-Wales). 10th Annual Report 2013.

- New Zealand Joint Registry . 15 Year Report.

- Paavolainen P, Hämälainen M, Mustonen H, Slatis P.. Registration of arthroplasties in Finland. A nationwide prospective project. Acta Orthop Scand 1991: (Suppl 241); 27–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puolakka TJ, Pajamaki K J, Halonen P J, Pulkkinen P O, Paavolainen P, Nevalainen J K.. The Finnish Arthroplasty Register: report of the hip register. Acta Orthop Scand 2001; 72 (5): 433–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O, Ranstam J.. No bias of ignored bilaterality when analysing the revision risk of knee prostheses: analysis of a population based sample of 44,590 patients with 55,298 knee prostheses from the national Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2003; 5: 4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seppänen M, Mäkelä K, Virolainen P, Remes V, Pulkkinen P, Eskelinen A.. Hip resurfacing arthroplasty: short-term survivorship of 4,401 hips from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2012; 83(3): 207–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Straeten C, Van Quickenborne D, De Roest B, Calistri A, Victor J, De Smet K.. Metal ion levels from well-functioning Birmingham Hip Resurfacings decline significantly at ten years. Bone Joint J 2013; 95-B(10): 1332–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Weegen W, Hoekstra H J, Sijbesma T, Austen S, Poolman R W.. Hip resurfacing in a district general hospital: 6-year clinical results using the ReCap hip resurfacing system. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012; 13: 247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vendittoli P A, Rivière C, Roy A G, Barry J, Lusignan D, Lavigne M.. Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing compared with 28-mm diameter metal-on-metal total hip replacement: a randomised study with six to nine years’ follow-up. Bone Joint J. 2013; 95-B: 1464–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zylberberg A D, Nishiwaki T, Kim P R, Beaulé P E.. Clinical results of the conserve plus metal on metal hip resurfacing: an independent series. J Arthroplasty 2015; 30(1): 68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]