Abstract

Background and purpose — Functional limitations after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are common. In this longitudinal study, we wanted to identify subgroups of patients with distinct trajectories of pain-related interference with walking during the first year after TKA and to determine which demographic, clinical, symptom-related, and psychological characteristics were associated with being part of this subgroup.

Patients and methods — Patients scheduled for primary TKA for osteoarthritis (n = 202) completed questionnaires that evaluated perception of pain, fatigue, anxiety, depression, and illness on the day before surgery. Clinical characteristics were obtained from the medical records. Interference of pain with walking was assessed preoperatively, on postoperative day 4, and at 6 weeks, 3 months, and 12 months after TKA.

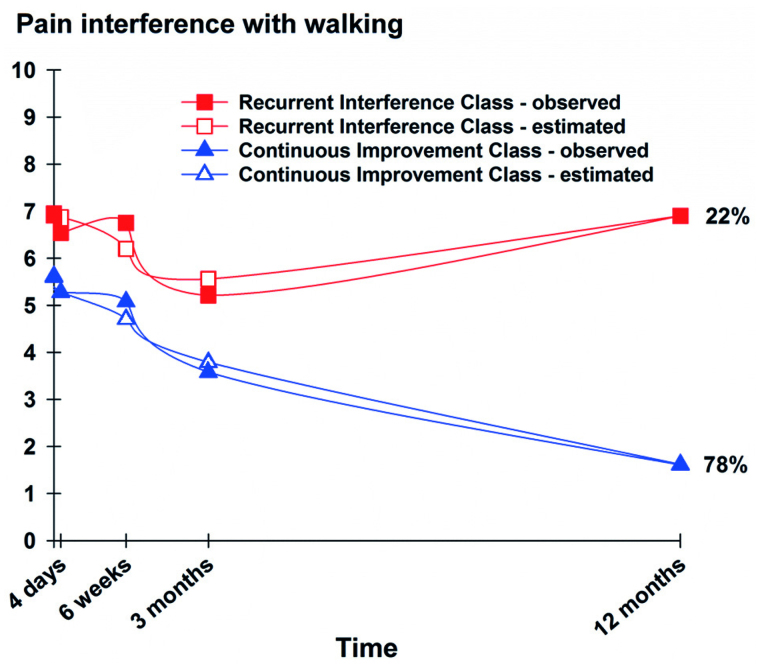

Results — Using growth mixture modeling, 2 subgroups of patients were identified with distinct trajectories of pain-related interference with walking over time. Patients in the Continuous Improvement class (n = 157, 78%) had lower preoperative interference scores and reported a gradual decline in pain-related interference with walking over the first 12 months after TKA. Patients in the Recurrent Interference class (n = 45, 22%) reported a high degree of preoperative pain-related interference with walking, initial improvement during the first 3 months after TKA, and then a gradual increase—returning to preoperative levels at 12 months. Patients in the Recurrent Interference class had higher preoperative pain, fatigue, and depression scores, and poorer perception of illness than the Continuous Improvement class.

Interpretation — 1 in 5 patients did not improve in pain-related interference with walking at 12 months after TKA. Future studies should test the efficacy of interventions designed to modify preoperative characteristics.

Between 10% and 34% of patients continue to report having pain 12 months after TKA (Beswick et al. 2012) and 11% report similar or worse levels of function after surgery (Wylde et al. 2007). The reasons for this variability in TKA outcomes are likely to be multifactorial (Jones et al. 2007, Kauppila et al. 2011). Although several studies have investigated demographic factors (O’Connor 2011), clinical factors (Kane et al. 2005), and psychological factors (Paulsen et al. 2011, Vissers et al. 2012) associated with functional recovery after TKA, the results have been inconclusive.

Newer methods of longitudinal data analysis (e.g. latent class analysis) can be used to identify subgroups of patients with distinct experiences of the outcome of interest over time (Jung and Wickrama 2008). In a large registry-based study (Franklin et al. 2008) that used mixture modeling to evaluate changes in functional status in patients after TKA, a subgroup of patients (37%) was identified who reported limited improvement in function. These patients were more likely to be older and female, and generally speaking they had a higher BMI, poorer emotional health, and poor quadriceps strength. However, in that study, function was measured only once postoperatively. We have not found any published studies that have attempted to identify subgroups of patients based on changes in functional status in the year following TKA.

We wanted to identify subgroups of patients with distinct trajectories of pain-related interference with walking in the first 12 months after TKA, and to determine which demographic, clinical, symptom-related, and psychological characteristics were associated with being part of these subgroups.

Material and methods

Patients and procedures

This study was performed from October 2012 through September 2014 in a high-volume surgical clinic in Norway. Patients (n = 202) were invited to participate on the day of admission if they were ≥18 years of age, literate in Norwegian, scheduled for primary TKA for OA, and had no diagnosis of dementia. Patients undergoing unicompartmental or revision surgery were not included. All patients received information about the study and signed the consent form before completing the enrollment questionnaire that assessed demographic, clinical, symptom-related, and psychological characteristics; preoperative pain; and interference of pain with walking. Pain-related interference with walking was assessed preoperatively, on postoperative day (POD) 4, and again at 6 weeks, 3 months, and 12 months. Follow-up questionnaires were mailed to each patient and returned in sealed envelopes. Clinical data were obtained from the medical records.

Pain management procedures

The procedures for anesthesia, surgery, and postoperative pain management were standardized. All patients received the same posterior cruciate-retaining fixed modular-bearing implant. A tourniquet was used during surgery, and drains were placed and removed on POD 1. Spinal anesthesia with bupivacaine and sedation was the first choice of anesthesia. Epidural analgesia (EDA) with continuous infusion of bupivacaine (1 mg/mL), adrenaline (2 μg/mL), and fentanyl (2 μg/mL; 5–12 mL/h) was used for postoperative pain management. If neuraxial blockade was contraindicated, patients received general anesthesia and a continuous femoral nerve block (CFNB) with bupivacaine (2.5 mg/mL; 4–10 mL/h) for postoperative pain management. Epidural catheters and femoral blocks were usually removed on POD2. Patients received oral acetaminophen (1 gram every 6 h), celecoxib (200 mg), and controlled-release oxycodone (5–20 mg every 12 h) unless contraindicated. Immediate-release oxycodone (5 mg tablets) and intravenous ketobemidone (2.5–5 mg) were available as rescue medications. If pain control was not satisfactory, low-dose ketamine (1.5 μg/kg/min) was administered as a continuous intravenous infusion. Pain medication prescribed at discharge usually consisted of acetaminophen and tramadol.

Physiotherapy procedures

All patients had the same protocol for recovery during hospitalization. Full weight bearing was allowed on the operated knee and physiotherapy was initiated on POD1 with walking, flexion, and extension of the knee. Most patients were discharged to home and continued to receive physiotherapy on a weekly basis for 4–6 months after surgery.

Pain and interference with function

Pain, interference with function, and number of painful sites was measured using the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) (Cleeland 1985). The BPI consists of 4 items that evaluate intensity of pain using a numeric rating scale (NRS) from 0 to 10 (with 0 meaning no pain and 10 meaning pain as bad as you can imagine); 7 items that evaluate pain-related interference with 7 different domains (general activity, mood, walking ability, work, social relations, sleep, enjoyment of life); and a body map to evaluate where pain is located. The validity and reliability of the BPI is well established (Klepstad et al. 2002). The dependent variable (i.e. interference of pain with walking) is the patients’ own ratings of how much their pain interfered with walking on a 0 (does not interfere) to 10 (completely interferes) NRS.

Symptom-related measures

Fatigue severity was evaluated using the 5-item Lee fatigue scale (LFS), with each item rated on a 0–10 NRS. A total score can range from 0 to 10; higher scores indicate higher severity of fatigue. The LFS has satisfactory validity and reliability (Lerdal et al. 2013). In this study, its Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91.

Fatigue interference was evaluated using the 7-item fatigue severity scale (FSS-7). Patients rated their agreement with 7 statements, using a 7-point Likert scale that ranged from “disagree” to “agree”. A total score can range from 1 to 7; higher scores indicate higher levels of interference. The FSS-7 has good psychometric properties (Lerdal et al. 2005). In this study, its Cronbach’s alpha was 0.93.

Anxiety and depression were evaluated using the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) (Zigmond and Snaith 1983). The scale consists of 7 items for depression and 7 items for anxiety. Scores can range from 0 to 21 on each subscale. Higher scores indicate higher levels of anxiety and depression. HADS has excellent psychometric properties (Mykletun et al. 2001). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha values for the depression and anxiety subscales were 0.79 and 0.84, respectively.

Psychological measure

The brief illness perception questionnaire (BIPQ) (Broadbent et al. 2006) was used to measure different dimensions of preoperative illness perceptions (i.e. consequences, personal control, identity, concern, and emotional response) in relation to the painful knee on a 0–10 NRS.

Data analysis

Data analyses were performed using SPSS version 22 and Mplus version 7.3 (Muthen 2015). A power analysis (alpha level =0.05, power =0.80, medium effect size (f = 0.25) for multiple regression) gave an estimated sample size of 180. Differences in demographic, clinical, symptom-related, and psychological characteristics between the latent classes were evaluated using independent-samples t-tests, Mann-Whitney U-tests, and chi-square analyses. Effect sizes were calculated on the differences between groups according to Cohen’s coefficient d. A d-value of ≥0.40 was considered to be a clinically meaningful difference (Cohen 1992).

Growth mixture modeling (GMM) with maximum likelihood estimation was used to identify latent classes (i.e. subgroups of patients) based on their distinct levels of interference of pain with walking—from before TKA until 12 months after. GMM allows for the estimation of more than 1 growth curve, for previously unidentified subgroups that change differently over time. A growth curve can be defined by an intercept and one or more slope coefficients. The intercept represents the estimated mean of pain-related interference with walking on the day before surgery for each class. The slope(s) represent(s) the estimated amount of change, per unit of time, in pain-related interference with walking over the 12 months after surgery.

Because the change over time had both a statistically significant linear component and quadratic component, we estimated coefficients for the intercept, a linear slope, and a quadratic slope for time coded in weeks. A single growth curve representing the mean change trajectory was estimated. Competing models with different numbers of latent classes were compared statistically to determine whether they provided a better model fit over the previous model. A lower Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and a statistically significant Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin (VLMR) likelihood test suggest a better model fit (Nylund et al. 2007, Jung and Wickrama 2008). Finally, visual inspection of plots of predicted values against observed values was performed. Any p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

With GMM, effects can be estimated using all cases even if some assessments are missing through the use of full-information maximum likelihood (Schafer et al. 2002) with the expectation-maximization algorithm (Muthén and Shedden 1999, Enders 2010). This method provides unbiased parameter estimates as long as the missingness can be ignored. Missingness in this study was not associated with previous measures of interference with function or covariates in the study.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Medical Research Ethics Committee of Health South East of Norway (no. 2011/1755).

Results

Of the 245 patients who were invited to participate, 33 declined and 6 had their surgery cancelled. 206 patients agreed to participate and were enrolled in the study. After enrollment, 2 patients were excluded due to postoperative disorientation and 1 patient was excluded due to revision surgery on the same knee. 1 patient died from postoperative complications, leaving 202 patients (98% of the included participants) for analysis.

Most participants were female (n = 138, 68%), lived with a partner (n = 122, 60%), had completed higher education (n = 102, 51%) and were not working (n = 130, 64%). The mean age was 68 (SD 9) years.

Using GMM, 2 distinct latent classes were identified. Based on the BIC and the VLMR likelihood test, the 2-class model provided a statistically significantly better model fit than the 1-class and 3-class models (Table 1). Visual inspection of the plots of the observed values against the estimated values showed that the predicted trajectories followed the empiric trajectories for both classes, which supports the idea that our 2-class model made sense conceptually and clinically. The classes were named Recurrent Interference and Continuous Improvement based on the shapes of their trajectories (Figure). The parameter estimates for the 2-class solution are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Fit indices for interference of pain with walking GMM solutions over 5 assessments

| GMM | LL | AIC | BIC | Entropy | VLMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain-related interference with walking | |||||

| 1-Classa | −2,136 | 4,290 | 4,319 | n/a | n/a |

| 2-Classb | −2,105 | 4,236 | 4,279 | 0.84 | 61c |

| 3-Class | −2,099 | 4,232 | 4,288 | 0.63 | 12d |

AIC: Akaike information criterion; BIC: Bayesian information criterion; CFI: comparative fit index; GMM: growth mixture model; LL: log likelihood; n/a: not applicable; RMSEA: root mean square error of approximation; SRMR: standardized root mean square residual; VLMR: Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test for K-1 (H0) vs. K classes.

Latent growth curve with linear and quadratic components; chi2 = 49.37, 11 df, p < 0.00005, CFI =0.69, RMSEA =0.13, SRMR =0.13.

2-class model was selected. The BIC was smallest for the 2-class model and the VLMR was consistent in indicating that the 2-class solution fitted the data better than the 1-class or 3-class solutions.

p < 0.001.

Not significant.

Table 2.

GMM parameter estimates for predicted growth mixture model latent classes from 5 assessments of pain-related interference with walking

| Recurrent Interference | Continuous Improvement | |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter estimates | (na = 45) mean (SE) | (na = 157) mean (SE) |

| Intercept | 6.96 (0.26)f | 5.63 (0.14)f |

| Linear slope | −0.14 (0.05)e | −0.16 (0.03)f |

| Quadratic slope | 0.003 (0.001)e | 0.002 (< 0.0005d)f |

| Variancesb | ||

| Interceptc | 0.97 (0.19)e | 0.97 (0.19)e |

GMM: growth mixture model; SE: standard error.

Predicted class sizes based on their most likely class membership.

Slope variances were fixed at zero to assist in estimation.

Intercept variances were set equal for the classes to aid in estimation, given the small sample size.

Standard error too small to be displayed with only 3 decimals in the Mplus output.

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

The total sample had a mean pain-related interference with walking score of 5.9 preoperatively, which decreased over time. Patients in the Recurrent Interference class (n = 45, 22%) were characterized by higher preoperative pain-related interference with walking scores (mean 7.0) that decreased over the next 3 months, followed by a gradual increase over the following 9 months, with return to preoperative levels at 12 months (Figure 1). Patients in the Continuous Improvement class (n = 157, 78%) were characterized by lower preoperative pain-related interference with walking scores (mean 5.6) that steadily decreased over the 12 months following TKA (Figure).

Trajectories of observed and estimated scores for the latent classes of pain-related interference with walking.

No statistically significant differences were found in any of the demographic and preoperative clinical characteristics between the 2 latent classes (Table 3, see Supplementary data). Patients in the Recurrent Interference class had higher average and worst pain intensity and higher total pain interference scores preoperatively, and a higher number of painful sites both preoperatively and at 12 months after surgery. More patients in this class had contraindications for regional anesthesia and received general anesthesia, peripheral nerve blocks, and ketamine as supplementary pain medication (Table 4, see Supplementary data).

Patients in the Recurrent Interference class had higher fatigue severity, fatigue interference, and depression scores preoperatively. In addition, patients in this class had higher scores for the preoperative illness perceptions regarding consequences, concern, and emotional response (Table 5).

Table 5.

Differences in symptom-related and psychological characteristics between the Recurrent Interference and Continuous Improvement classes based on an evaluation of pain-related interference with walking

| Recurrent | Continuous | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interferencea | Improvementa | Statistics |

Effect size | ||

| (n = 45) | (n = 157) | p-value | 95% CI | Cohen’s d | |

| Symptoms | |||||

| Fatigue severity (LFS) | 3.4 (2.1) | 2.6 (2.1) | 0.02 | −1.6 to −1.4 | 0.37 |

| Fatigue interference (FSS7) | 4.6 (1.6) | 3.8 (1.5) | 0.005 | −1.3 to −0.2 | 0.52 |

| Depression (HADS) | 4.6 (3.9) | 3.2 (2.8) | 0.03 | −2.7 to −0.1 | 0.44 |

| Anxiety (HADS) | 5.4 (4.1) | 4.4 (3.5) | 0.1 | −2.2 to 0.2 | 0.28 |

| Psychological characteristics from the brief illness perception questionnaire | |||||

| Consequences | 6.8 (1.6) | 6.2 (1.8) | 0.04 | −1.2 to −0.03 | 0.34 |

| Personal control | 5.9 (2.4) | 5.2 (2.4) | 0.06 | −1.6 to 0.02 | 0.30 |

| Identity | 7.0 (1.6) | 6.5 (1.7) | 1.0 | −1.0 to 0.1 | 0.30 |

| Concern | 6.2 (2.3) | 4.7 (2.6) | < 0.001 | −2.4 to −0.7 | 0.76 |

| Emotional response | 5.3 (2.5) | 4.3 (2.6) | 0.02 | −1.9 to −0.2 | 0.38 |

Values are mean (SD)

Cohen’s d effect sizes: Small ≥0.2; Medium ≥0.5; Large ≥0.8.

FSS7: fatigue severity scale; HADS: hospital and anxiety scale; LFS: Lee fatigue scale.

Discussion

This study is the first to use GMM to identify patient subgroups with distinct trajectories of pain-related interference with walking during the first year after TKA. Strikingly, while most patients experienced substantial improvements, one fifth reported no improvement in their level of pain-related interference with walking 12 months after surgery. Finally, our study identified a number of factors that may help clinicians identify patients who are at risk of having poorer functional outcomes.

Consistent with previous reports, our findings suggest that TKA is not effective in a number of patients. For example, Kauppila et al. (2011) found that 12 months after TKA, one tenth of patients had worse functional scores. In another study, one third of patients reported limited functional improvements after 12 months (Franklin et al. 2008). Patients in our Recurrent Interference class showed improvements until 3 months after surgery, but the results were not sustained beyond 3 months. Interestingly, the recurrence of pain-related interference with walking appeared to coincide in time with the cessation of physiotherapy. The effects of more intense or prolonged postoperative physiotherapy on walking in high-risk patients should be tested in future studies.

Patients in the Recurrent Interference class reported having a higher intensity of preoperative pain and a higher number of painful sites. Similarly, a higher number of painful joints has been associated with worse pain and poorer functional outcomes after TKA (Perruccio et al. 2012, Hawker et al. 2013).

Our study is the first to document the relationship between preoperative fatigue and interference of pain with walking following TKA. Fatigue levels in our sample (mean 3.9) were slightly higher than in patients with OA (mean 3.63) (Cross et al. 2008), but similar to those in the general population of Norway (mean 3.98) (Lerdal et al. 2005). It is noteworthy that the mean difference in fatigue interference scores between the 2 classes was 0.8—a clinically important difference for this scale (Rosa et al. 2014).

While the depression levels in our sample (mean 3.5) were well below the HADS subscale cutoff of >7 (Bjelland et al. 2002) and comparable to data from the general Norwegian population (male mean: 3.5; female mean: 3.4) (Stordal et al. 2001), the depression scores were higher in the Recurrent Interference class than in the Continuous Improvement class. Although a systematic review found inconclusive results for the impact of preoperative distress on function (Paulsen et al. 2011), our findings are consistent with several recent studies (Judge et al. 2012, Duivenvoorden et al. 2013, Singh and Lewallen 2014). There is growing evidence to suggest that depression and pain share similar phenotypic characteristics and biological mechanisms (Bair et al. 2003, Gambassi 2009), and both are associated with physical impairments (Bair et al. 2003).

While psychological factors are considered important in explaining long-term functional outcomes after TKA (Jones et al. 2007), illness perceptions after TKA are not well studied. Illness perceptions based on the self-regulatory model of Leventhal and colleagues (Leventhal et al. 1992, Broadbent et al. 2006) describes individuals’ response to perceived threats to health and how beliefs about their illness can affect adherence to treatment regimens. Of the 4 BIPQ items associated with latent class membership, illness-related concern had the largest effect size. Similarly, in another study, preoperative illness-related concern was found to be associated with poorer functional outcome 1 year after TKA (Bethge et al. 2010). There was a correlation between a higher degree of distress and lower use of problem-focused coping strategies (Folkman and Moskowitz 2004), which may in turn result in avoidance of activity. Preliminary findings from a recent quasi-experimental study (Riddle et al. 2011) have suggested that coping-skills training in patients with elevated catastrophizing levels may improve function after TKA.

Preoperatively, patients in the Recurrent Interference class were more likely to perceive more severe consequences in their lives from their OA. Correspondingly, perception of more severe consequences from the OA condition before surgery was associated with lower activity levels at 9 months (Orbell et al. 1998) and poorer range of motion of the knee 6 weeks and 1 year after TKA (Hanusch et al. 2014). In a recent review of the BIPQ, perceived consequences were among the single dimensions that were found to be most predictive of future outcomes (Broadbent et al. 2015). Illness perceptions are considered to be modifiable beliefs (Broadbent et al. 2006).

Patients in the Recurrent Interference class were more likely to have received general anesthesia and supplemental pain management with ketamine. While their prevalence of comorbidity was not higher, our study may have been underpowered to detect statistically significant differences. Medical conditions or associated drug therapies may be confounders in this analysis. For example, patients on anticoagulation therapy cannot have neuraxial blocks, and such confounders might contribute to the association between general anesthesia and poorer outcomes. The safety, efficacy, and opioid-sparing effect of CFNB after TKA is well established (Fowler et al. 2008, Chan et al. 2014). The NMDA receptor antagonist ketamine prevents allodynia and may reduce the risk of chronic pain (Aveline et al. 2014). Thus, our findings should be interpreted with caution.

The study had several limitations. The sample was recruited at a single surgical clinic, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Assessments between 3 and 12 months would have provided additional information. No data are available on previous knee injuries that may have led to the OA condition, on analgesic consumption after discharge, on adherence to physiotherapy, and on patients’ willingness to become more physically active. No information is available about the nature of the patients’ persistent pain after TKA. More detailed data on other chronic pain conditions and their relationship to functional status might have enabled us to distinguish better between these conditions and knee-related functional limitations.

The large sample size, the prospective design, and the low attrition rate were advantages. Our statistical approach allowed us to identify subgroups with distinct trajectories over time and to explore a comprehensive list of characteristics associated with subgroup membership.

In conclusion, 1 in 5 patients had no improvement in pain-related interference with walking 12 months after TKA. Based on our findings, a screening tool to identify patients with higher risk should be developed and tested. Finally, development and testing of interventions that target these characteristics is warranted, to improve outcomes after TKA surgery.

Supplementary data

Tables 3 and 4 are available on the website of Acta Orthopaedica (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 10210.

CM, TR, LA, AL, and ML developed and designed the study. ML and BC performed the statistical analyses. All the authors appraised the data, contributed to preparation of the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

The study was funded by Lovisenberg Diakonale Hospital. The PhD fellowship held by ML was provided by Lovisenberg Diakonale Hospital, the Norwegian Nursing Organization, and the Fulbright Foundation. None of the sources of funding were involved in the study.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Aveline C, Roux A L, Hetet H L, Gautier J F, Vautier P, Cognet F, Bonnet F.. Pain and recovery after total knee arthroplasty: a 12-month follow-up after a prospective randomized study evaluating Nefopam and Ketamine for early rehabilitation. Clin J Pain 2014; 30 (9): 749–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bair M J, Robinson R L, Katon W, Kroenke K.. Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163 (20): 2433–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beswick A D, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, Blom A, Dieppe P.. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ open 2012; 2 (1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethge M, Bartel S, Streibelt M, Lassahn C, Thren K.. [Illness perceptions and functioning following total knee and hip arthroplasty]. Z Orthop Unfall 2010; 148 (4): 387–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjelland I, Dahl A A, Haug T T, Neckelmann D.. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 2002; 52 (2): 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent E, Petrie K J, Main J, Weinman J.. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res 2006; 60 (6): 631–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent E, Wilkes C, Koschwanez H, Weinman J, Norton S, Petrie K J.. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire. Psychol Health 2015; 30 (11): 1361–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan E Y, Fransen M, Parker D A, Assam P N, Chua N.. Femoral nerve blocks for acute postoperative pain after knee replacement surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 5: Cd009941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleeland C S. Measurement and prevalence of pain in cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs 1985; 1 (2): May-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992; 112 (1): 155–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross M, Lapsley H, Barcenilla A, Brooks P, March L.. Association between measures of fatigue and health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Patient 2008; 1 (2): 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duivenvoorden T, Vissers M M, Verhaar J A, Busschbach J J, Gosens T, Bloem R M, Bierma-Zeinstra S M, Reijman M.. Anxiety and depressive symptoms before and after total hip and knee arthroplasty: a prospective multicentre study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013; 21 (12): 1834–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders C K. Applied missing data analysis. Guilford Press, New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Moskowitz J T.. Coping: pitfalls and promise. Annu Rev Psychol 2004; 55: 745–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler S J, Symons J, Sabato S, Myles P S.. Epidural analgesia compared with peripheral nerve blockade after major knee surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth 2008; 100 (2): 154–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin P D, Li W, Ayers D C.. The Chitranjan Ranawat Award: functional outcome after total knee replacement varies with patient attributes. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008; 466 (11): 2597–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambassi G. Pain and depression: the egg and the chicken story revisited. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2009; 49Suppl1: 103–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanusch B C, O’Connor D B, Ions P, Scott A, Gregg P J.. Effects of psychological distress and perceptions of illness on recovery from total knee replacement. Bone Joint J 2014; 96-b (2): 210–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawker G A, Badley E M, Borkhoff C M, Croxford R, Davis A M, Dunn S, Gignac M A, Jaglal S B, Kreder H J, Sale J E.. Which patients are most likely to benefit from total joint arthroplasty? Arthritis Rheum 2013; 65 (5): 1243–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C A, Beaupre L A, Johnston D W, Suarez-Almazor M E.. Total joint arthroplasties: current concepts of patient outcomes after surgery. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2007; 33 (1): 71–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge A, Arden N K, Cooper C, Kassim Javaid M, Carr A J, Field R E, Dieppe P A.. Predictors of outcomes of total knee replacement surgery. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012; 51 (10): 1804–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung T, Wickrama K A S.. An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 2008; 2 (1): 302–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kane R L, Saleh K J, Wilt T J, Bershadsky B.. The functional outcomes of total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87 (8): 1719–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauppila A M, Kyllonen E, Ohtonen P, Leppilahti J, Sintonen H, Arokoski J P.. Outcomes of primary total knee arthroplasty: the impact of patient-relevant factors on self-reported function and quality of life. Disabil Rehabil 2011; 33 (17-18): 1659–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klepstad P, Loge J H, Borchgrevink P C, Mendoza T R, Cleeland C S, Kaasa S.. The Norwegian brief pain inventory questionnaire: translation and validation in cancer pain patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002; 24 (5): 517–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerdal A, Wahl A, Rustoen T, Hanestad B R, Moum T.. Fatigue in the general population: a translation and test of the psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the fatigue severity scale. Scand J Public Health 2005; 33 (2): 123–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerdal A, Kottorp A, Gay C L, Lee K A.. Development of a short version of the Lee Visual Analogue Fatigue Scale in a sample of women with HIV/AIDS: a Rasch analysis application. Qual Life Res 2013; 22 (6): 1467–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Diefenbach M, Leventhal E.. Illness cognition: Using common sense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cognit Ther Res 1992; 16 (2): 143–63. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Shedden K.. Finite mixture modeling with mixture outcomes using the EM algorithm. Biometrics 1999; 55 (2): 463–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen L K M, B.O. (1998-2015) Mplus User’s Guide. 7 ed. Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles, CA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mykletun A, Stordal E, Dahl A A.. Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale: factor structure, item analyses and internal consistency in a large population. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 179: 540–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund K L, Asparouhov T, Muthén B O.. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct Equ Modeling 2007; 14 (4): 535–69. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor M I. Implant survival, knee function, and pain relief after TKA: are there differences between men and women? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011; 469 (7): 1846–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orbell S, Johnston M, Rowley D, Espley A, Davey P.. Cognitive representations of illness and functional and affective adjustment following surgery for osteoarthritis. Social science & medicine (1982) 1998; 47 (1): 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen M G, Dowsey M M, Castle D, Choong P F.. Preoperative psychological distress and functional outcome after knee replacement. ANZ J Surg 2011; 81 (10): 681–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perruccio A V, Power J D, Evans H M, Mahomed S R, Gandhi R, Mahomed N N, Davis A M.. Multiple joint involvement in total knee replacement for osteoarthritis: Effects on patient-reported outcomes. Arthritis Care Res 2012; 64 (6): 838–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle D L, Keefe F J, Nay W T, McKee D, Attarian D E, Jensen M P.. Pain coping skills training for patients with elevated pain catastrophizing who are scheduled for knee arthroplasty: a quasi-experimental study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011; 92 (6): 859–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa K, Fu M, Gilles L, Cerri K, Peeters M, Bubb J, Scott J.. Validation of the Fatigue Severity Scale in chronic hepatitis C. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2014; 12: 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J L, Graham J W, West S G.. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods 2002; 7 (2): 147–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J A, Lewallen D G.. Depression in primary TKA and higher medical comorbidities in revision TKA are associated with suboptimal subjective improvement in knee function. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014; 15: 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stordal E, Bjartveit Kruger M, Dahl N H, Kruger O, Mykletun A, Dahl A A.. Depression in relation to age and gender in the general population: the Nord-Trondelag Health Study (HUNT). Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001; 104 (3): 210–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissers M M, Bussmann J B, Verhaar J A, Busschbach J J, Bierma-Zeinstra S M, Reijman M.. Psychological factors affecting the outcome of total hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2012; 41 (4): 576–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylde V, Dieppe P, Hewlett S, Learmonth I D.. Total knee replacement: is it really an effective procedure for all? Knee 2007; 14 (6): 417–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond A S, Snaith R P.. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983; 67 (6): 361–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]