Abstract

Background and purpose

Antibiotic treatment of patients before specimen collection reduces the ability to detect organisms by culture. We investigated the suppressive effect of antibiotics on the growth of non-adherent, planktonic, and surface-related biofilm bacteria in vitro by using sonication and microcalorimetry methods.

Patients and methods

Biofilms of Staphylococcus aureus, S. epidermidis, Escherichia coli, and Propionibacterium acnes were formed on porous glass beads and exposed for 24 h to antibiotic concentrations from 1 to 1,024 times the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of vancomycin, daptomycin, rifampin, flucloxacillin, or ciprofloxacin. The beads were then sonicated to dislodge biofilm, followed by culture and measurement of growth-related heat flow by microcalorimetry of the resulting sonication fluid.

Results

Vancomycin did not inhibit the heat flow of staphylococci and P. acnes at concentrations ≤1,024 μg/mL, whereas flucloxacillin at >128 μg/mL inhibited S. aureus. Daptomycin inhibited heat flow of S. aureus, S. epidermidis, and P. acnes at lower concentrations (32–128 times MIC, p < 0.001). Rifampin showed inconsistent results in staphylococci due to random emergence of resistance, which was observed at concentrations ≤1,024 times MIC (i.e. 8 μg/mL). Ciprofloxacin inhibited heat flow of E. coli at ≥4 times MIC (i.e. ≥ 0.06 μg/mL).

Interpretation

Whereas time-dependent antibiotics (i.e. vancomycin and flucloxacillin) showed only weak growth suppression, concentration-dependent drugs (i.e. daptomycin and ciprofloxacin) had a strong suppressive effect on bacterial growth and reduced the ability to detect planktonic and biofilm bacteria. Exposure to rifampin rapidly caused emergence of resistance. Our findings indicate that preoperative administration of antibiotics may have heterogeneous effects on the ability to detect biofilm bacteria.

Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) is a serious complication with a reported incidence rate of 0.6–2.2% (Dale et al. 2012, Kurtz et al. 2012). The true incidence can be expected to be higher, though, due to under-reporting in the national databases (Huotari et al. 2010, Gundtoft et al. 2015) and imperfect diagnostic methods (Zimmerli et al. 2004).

For successful treatment, the diagnostic procedure involves isolation of the causative organism (Kamme and Lindberg 1981, Spangehl et al. 1999). Microorganisms living on the biologically inert surfaces of prosthetic components produce an organized community called biofilm (Gbejuade et al. 2014). These adherent biofilm bacteria can withstand host immune responses and are much less susceptible to antibiotics than their non-adherent, planktonic counterparts (Costerton et al. 1999).

Biofilm bacteria are often inaccessible with conventional sampling of synovial fluid and periprosthetic tissue samples, especially after eradication of the non-adherent bacteria by previous antibiotic treatment—e.g. empirical antibiotic therapy during postoperative wound healing complications or previous infections (Berbari et al. 2007, Malekzadeh et al. 2010). This has led to the use of sonication, which was introduced to improve the sensitivity of culture from biofilm infections by dislodgement of adherent bacteria from implant surfaces (Trampuz et al. 2007a).

To address the challenges of detecting slow-growing bacteria and reduced bacterial numbers after previous exposure to antibiotic, isothermal microcalorimetry has been found to be a highly sensitive and accurate method (Trampuz et al. 2007b, von Ah et al. 2008, Furustrand Tafin et al. 2012a, Maiolo et al. 2014). The principle of microcalorimetry relies on microbial heat production from bacterial growth and metabolism (Boling et al. 1973). Real-time measurement of exponential bacterial growth results in a pyramid-shaped heat-flow curve. The effect of antibiotics on recovery of bacterial growth can be followed by delayed detection of heat flow and reduction of the peak heat flow (Furustrand Tafin et al. 2011, Furustrand Tafin et al. 2012b, Mihailescu et al. 2014).

The main aim of this study was to determine the antimicrobial susceptibility of tested planktonic and biofilm bacteria in order to correlate biofilm detection with antibiotic exposure. A secondary aim was to investigate the effect of antibiotic exposure on detection of biofilm bacteria by sonication, culture, and microcalorimetry. We specifically investigated the effects of individual antibiotics in inhibiting the growth of planktonic and biofilm bacteria. Microcalorimetric measurement of heat flow was compared with conventional viable counting of dislodged biofilm bacteria.

Material and methods

This experimental study was designed to determine the effect of different antibiotics that are usually used in the treatment of PJI on the detection of biofilm bacteria by sonication and microcalorimetry, and to compare these results with those from conventional quantitative culture.

Test organisms and antimicrobial agents

Laboratory strains of bacteria that commonly cause PJI were studied, including methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 29213), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (ATCC 35984), Propionibacterium acnes (ATCC 11827), and Gram-negative ciprofloxacin-susceptible Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922). Bacterial strains were stored at −80 °C and cultured overnight on sheep blood agar plates before each experiment. Anaerobic culture conditions (Anaerogen system; Oxoid) and prolonged incubation (72 h) were used for all experiments with P. acnes in order to get visible colonies. The following antibiotics were used: vancomycin (Teva Pharma AG), daptomycin (Novartis Pharma AG), rifampin (Sandoz AG), flucloxacillin (Actavis SA), and ciprofloxacin (Bayer AG). For comparative reasons, the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) was initially determined for each combination of antibiotics and bacteria according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (CLSI 2012).

Biofilm formation on glass beads

Biofilms were investigated using porous glass beads (VitraPOR; Robu Glasfilter-geräte GmbH; diameter 4 mm, pore size 40–100 μm) (Corvec et al. 2013). For biofilm formation, beads were placed in 50-mL Falcon tubes containing tryptic soy broth (TSB) (1 mL per bead) and inoculated with 2 CFU of microorganisms as specified above. The beads were then incubated aerobically for 24 h at 37 °C (brain heart infusion (BHI), 72 h, anaerobically for P. acnes). After the incubation, they were washed 5 times through rinsing with 10 mL saline, gentle shaking, and aspiration in order to minimize carryover of planktonic and loosely attached bacteria on the biomaterial surface.

Antibiotic exposure of biofilm

2-fold dilutions of antibiotic were prepared in TSB, or BHI for P. acnes, with concentrations ranging from 1 MIC up to 1,024 times MIC. Beads with biofilm bacteria were transferred with sterile forceps to the individual tubes (containing TSB and different antibiotic concentrations) and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C (anaerobically, 72 h for P. acnes). Experiments were performed independently in triplicate and were accompanied with a growth control consisting of an inoculated glass bead without antibiotics and one negative control of a sterile glass bead in antibiotic-free medium.

Removal of biofilm by sonication

After exposure to antibiotic, the beads were transferred to individual Eppendorf tubes with 1 mL saline, vortexed for 30 s with maximum power (Vortex Genie 2; Scientific Industries), sonicated for 60 s (BactoSonic; Bandelin Electronic), and vortexed for 30 s again to dislodge biofilm-embedded bacteria. For conventional culture, 50-μL samples of the resulting sonication fluid were serially diluted and plated on blood agar plates. Bacteria in the sonication fluid were quantified by viable count of colony-forming units per mL (CFU/mL).

Detection of dislodged bacteria by microcalorimetry

In parallel to taking viable counts, 0.1 mL of sonication fluid from each experiment was added to 4-mL microcalorimetry glass ampoules with 1 mL TSB (3.9 mL BHI for P. acnes) (Clauss et al. 2010, Furustrand Tafin et al. 2012b, Corvec et al. 2013). After sealing the ampoules, they were lowered into a 48-channel batch microcalorimeter (thermal activity monitor model 3102 TAM III; TA Instruments). Heat flow (in μW) at 37.0000 °C was measured continuously for 24 h (72 h for P. acnes) with an analytical sensitivity of ±0.2 μW. The experimental detection limit was set at 10 μW to distinguish microbial heat production from the thermal background. Time to detection (TTD) was defined as the length of time (in hours) for a microcalorimeter experiment to reach the detection limit, which was therefore inversely proportional to the initial quantity of bacteria and the growth rate. The results were plotted as heat flow over time using the manufacturer’s software (TAM Assistant; TA Instruments) and Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The minimal heat inhibitory concentration (MHIC) was defined as the lowest antibiotic concentration (in μg/mL) to kill bacteria on the beads, or to show a post-antibiotic effect of inhibiting bacterial growth, leading to absence of heat production from biofilm-dislodged bacteria after 24 h of incubation in the microcalorimeter (72 h for P. acnes). In relation to the MIC of planktonic bacteria, the MHIC value is a multiplication factor on an ordinal scale from 1 MIC to 1,024 times MIC.

Susceptibility of test organisms to vancomycin, daptomycin, rifampin, flucloxacillin, and ciprofloxacin. The results are expressed as minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) for non-adherent, planktonic bacteria and as minimal heat inhibitory concentration (MHIC) for biofilm bacteria. Numbers are in μg/mL

| Vancomycin |

Daptomycin |

Rifampin |

Flucloxacillin |

Ciprofloxacin |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | MIC | MHIC | MIC | MHIC | MIC | MHIC | MIC | MHIC | MIC | MHIC |

| S. aureus | 1 | > 1,024 | 0.5 | 64 | 0.007 | 8 | 0.25 | 128 | ND | ND |

| S. epidermidis | 2 | > 1,024 | 1 | 64 | 0.007 | 8–16a | IR | IR | ND | ND |

| E. coli | IR | IR | IR | IR | IR | IR | IR | IR | 0.015 | 0.063–0.25a |

| P. acnes | 1 | > 1,024 | 1 | 32 | 0.007 | 8–16a | ND | ND | ND | ND |

IR, intrinsic resistance; ND, not done.

In 3 cases where small variations were observed in experiments done in triplicate, the results are given as range.

Statistics

Experiments were performed in triplicate, and descriptive statistics were used to express the median and range of all data. Non-parametric comparisons of antimicrobial susceptibility in 3 Gram-positive microorganisms were based on the multiplication factors and they were performed by Wilcoxon signed-rank test using GraphPad Prism 7.0. Direct comparison with the MHIC of ciprofloxacin in Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli) was deemed unsuitable.

Results

Susceptibility of planktonic and dislodged biofilm bacteria to antibiotics

The Table summarizes the inhibition of microbial growth, expressed as the antimicrobial susceptibility of biofilm bacteria—as determined by sonication and microcalorimetry (MHIC)—relative to the MIC of planktonic bacteria. MHIC was considerably higher than MIC for all test strains and antibiotics (4 times to more than 1,024 times). According to CLSI breakpoints, the bacterial strains were susceptible to all antibiotics tested. The MHIC for vancomycin was more than 1,024 μg/mL for both staphylococci and P. acnes. The high MHIC values for rifampin reflect the emergence of resistance in staphylococci and P. acnes, as confirmed by susceptibility testing of the organisms after antibiotic exposure. The MHIC values were lowest for ciprofloxacin in E. coli (0.063 μg/mL), except in 1 of 5 experiments, where the MHIC was 0.25 μg/mL, reflecting emergence of ciprofloxacin resistance. In relation to the multiplication factor, the MHIC of daptomycin in Gram-positive bacteria was significantly lower than that of vancomycin (p < 0.001), rifampin (p < 0.001), and flucloxacillin (p = 0.03).

Effect of antibiotic exposure on detection of biofilm bacteria by microcalorimetry

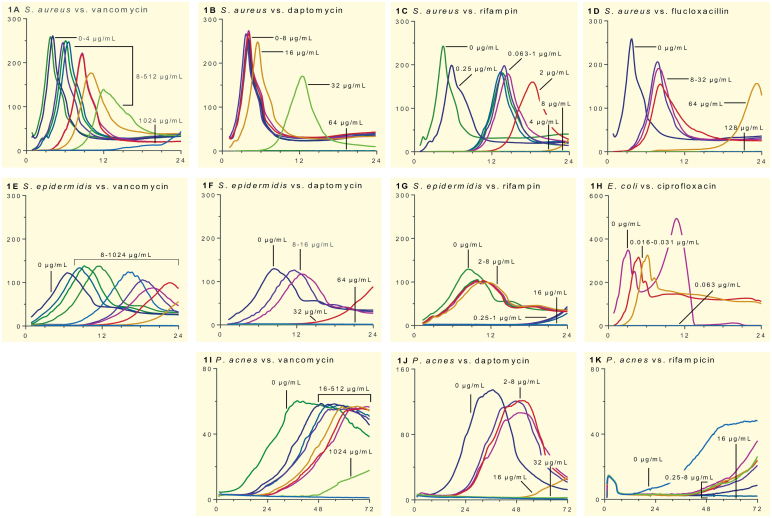

Figure 1 shows the heat flow of bacteria after exposure to antibiotic, as a function of time. The heat-flow curves of organisms without previous antibiotic exposure had specific characteristics for each test bacterium, including the peak heat flow and shape of the curve. The time-shift of the curves to the right shows the delayed bacterial detection due to the lower quantity of bacteria in the sonication fluid from beads exposed to increasing concentrations of vancomycin, daptomycin, rifampin, flucloxacillin (only for S. aureus), and ciprofloxacin (only for E. coli). With rifampin, emergence of resistance was observed in S. aureus (Figure 1C) and S. epidermidis (Figure 1G) from heat production at higher antibiotic concentrations.

Figure 1.

Heat flow (y-axis, μW) development over time (x-axis, hours) of S. aureus (panels A–D), S. epidermidis (E–G), E. coli (H), and P. acnes (I–K) exposed to different antibiotics. The numbers above each curve indicate the respective antibiotic concentrations. The range for x-axis is different in the case of P. acnes (72 h). Furthermore, y-axis range was changed for non-staphylococci that showed markedly different heat flow levels. The positive controls were biofilms on beads not previously exposed to antibiotics (0 μg/mL). The experiments were performed in triplicate, and a representative experiment is shown.

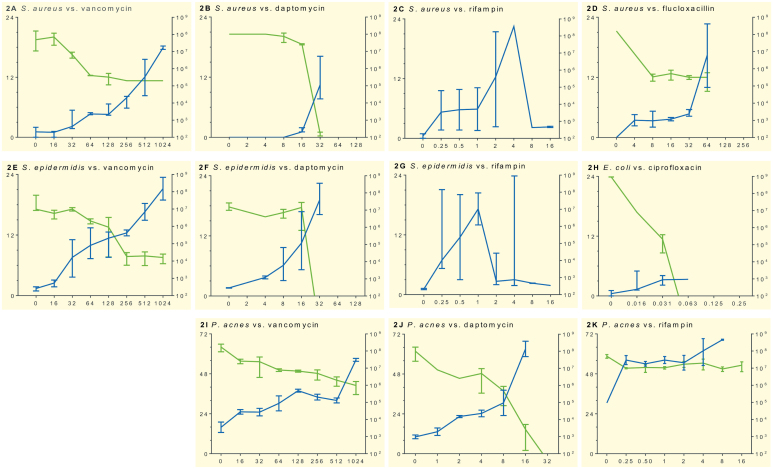

Figure 2 shows the time to heat detection. Fast-growing, high-virulence bacteria such as S. aureus (Figure 2A–D) and E. coli (Figure 2H) are detected earlier and produce a higher peak of heat flow compared to less virulent and more slowly growing bacteria (S. epidermidis (Figure 2E–G) and P. acnes (Figure 2I–K)). In addition, we observed the different modes of action of the antibiotics tested. Exposure to fast-acting antibiotics (such as daptomycin, rifampin, and ciprofloxacin) resulted in inhibition of heat flow at lower concentrations relative to the MIC and a more potent anti-biofilm activity compared to more slowly acting drugs (such as vancomycin and flucloxacillin). The high variability in heat flow after exposure to rifampin was due to spontaneous development of resistance, as confirmed by susceptibility testing.

Figure 2.

Growth inhibition of various antibiotics on S. aureus (panels A–D), S. epidermidis (E–G), E. coli (H), and P. acnes (I–K) in sonication fluid, determined by microcalorimetry and culture. The x-axis shows increasing antibiotic concentrations (μg/mL). The green line represents median bacterial concentration (corresponding to y-axis on right, in CFU/mL) determined by viable count in 3 independent experiments; bars indicate range. The blue line represents median time to detection (corresponding to y-axis on left, in hours) in the microcalorimeter experiment. It demonstrates how significant bacterial heat flow (> 10 μW) is detectable within a few hours. Spontaneous emergence of staphylococcal resistance to rifampin was observed in replicates of experiments C and G.

In parallel to the microcalorimetric assay, the presence of bacteria in the sonication fluid was assessed by viable counts on conventional cultures (also shown in Figure 2). The culture results from repeated experiments with S. aureus (Figure 2C) and S. epidermidis (Figure 2G) exposed to rifampin showed a high degree of heterogeneity due to random emergence of resistance, and the data are therefore not shown.

Discussion

A correct and timely microbial diagnosis is a crucial step in determining the treatment of PJI, but antibiotic treatment before collection of periprosthetic tissue samples may lead to false-negative culture results (Kamme and Lindberg 1981, Spangehl et al. 1999, Trampuz et al. 2004, Achermann et al. 2010). In the present study, we investigated the effect of exposure of a young (24-h) biofilm on porous glass beads to antibiotic under in vitro conditions, using sonication and microcalorimetry.

We believe that this experimental study has clinical relevance regarding the challenge of establishing a bacterial diagnosis in cases with previous exposure to antibiotics (e.g. in recurrent infections or antibiotic prophylaxis).

Our materials included 4 bacteria that commonly cause PJI (Zappe et al. 2008, Stefansdottir et al. 2009), but which have differences in virulence pattern, metabolism, and Gram-stainability. Empirical antimicrobial treatment for PJI may include vancomycin and flucloxacillin for Gram-positive microorganisms or ciprofloxacin for Gram-negative microorganisms (Zimmerli and Moser 2012). Specific combinations with biofilm-penetrating rifampin are recommended under certain circumstances, and novel antibiotics such as daptomycin have been introduced in recent therapeutic studies (Zimmerli and Moser 2012). The rationale for antibiotic selection in this study was to test drugs with different properties regarding mode of action (concentration- or time-dependent), bactericidal activity (fast- or slow-killing), and existence of anti-biofilm activity (Asin et al. 2012).

The limitations of our study design included lack of important in vivo information about conditions such as antimicrobial pharmacokinetics (dose, tissue penetration, repeated administration, duration of treatment), the host immune response, and the fact that the artificial porosity of glass beads might not necessarily reflect that of commonly used prosthetic material. Also, we did not try to investigate the sonication fluid for the possible presence of viable—but non-cultivable—bacteria that produce less metabolism-related and growth-related heat flow.

Concerning antimicrobial susceptibility testing, for all test strains and antibiotics, the biofilm bacteria were 4 to >1,024 times more resistant than non-adherent, planktonic bacteria, as determined by comparison of microcalorimetry (MHIC) and the MIC. The low doses achieved with systemic antibiotic therapy may alleviate symptoms caused by planktonic bacteria, but this barely affects the biofilm bacteria (Costerton 2005). According to CLSI breakpoints, the planktonic strains were susceptible to all the antibiotics tested. The MHIC for vancomycin was >1024 μg/mL in the case of staphylococci and P. acnes biofilms. Vancomycin has previously been found to be less effective against staphylococcal biofilms (Monzon et al. 2002, Molina-Manso et al. 2013). The inconsistently high MHIC values for rifampin reflect the random emergence of resistance in staphylococci and P. acnes, as confirmed by susceptibility testing of the organisms after antibiotic exposure. The observation of spontaneous development of resistance to rifampin shows that a high bacterial concentration is a risk factor for emergence of resistance. These results confirm that rifampin should not be used as a single therapy or before sufficient surgical debridement, as has been recommended previously (Zimmerli et al. 2004, Furustrand Tafin et al. 2012b). The MHIC values were lowest for ciprofloxacin in E. coli (0.063 μg/mL), except in 1 of 5 experiments, where the MHIC was 0.25 μg/mL—reflecting the emergence of ciprofloxacin resistance.

Concerning the effect of antibiotic exposure on detection of biofilm bacteria, vancomycin did not reduce the ability to detect staphylococci and P. acnes in biofilms, even at very high (non-physiological) concentrations. Thus, our results call into question the short-term (24-hour) effect of vancomycin, which is often used in bone cement spacer to give high local concentrations, on eradication of biofilm bacteria. Daptomycin was the most active antibiotic, inhibiting staphylococci at 64 μg/mL and P. acnes at 32 μg/mL. Ciprofloxacin inhibited E. coli even at very low concentrations (MHIC 0.063 μg/mL). Flucloxacillin and rifampin inhibited Gram-positive bacteria, but only at higher concentrations than the MIC. The high culture yield from sonication fluid found in this study suggests that sonication is an efficient method to facilitate detection of biofilm bacteria despite antibiotic exposure (Trampuz et al. 2007a). However, our findings also suggest that using concentration-dependent antibiotics preoperatively may reduce the ability of a sonication-based method to detect the bacteria, whereas time-dependent antibiotics may be safer.

A recent randomized clinical trial did not find impaired intraoperative culture results in PJI as a consequence of using single-dose antibiotic prophylaxis (Tetreault et al. 2014). The authors suggested that perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis should be administered before surgery and before intraoperative sampling. We investigated a young (24-hour) biofilm, which might not be entirely relevant to the clinical situation where infection has usually been present for more than 24 hours. Under these conditions, it appears that a single dose of antibiotics does not reduce the sensitivity of a sonication-culture method. Whether this would also be true for mature biofilms remains to be elucidated.

The combined action of sonication and microcalorimetry might be useful in investigation of pre-exposure of biofilm-embedded bacteria to antibiotic. Furthermore, the high inter-experimental repeatability of the microcalorimetry assay in this and other studies suggests that the method is a valid test for investigation of dislodged biofilms (Clauss et al. 2010, Borens et al. 2013). Additional advantages of microcalorimetry are the fast detection of heat flow (within a few hours) from microbial metabolism in sonication fluid and real-time evaluation of the interaction between antibiotics and biofilm bacteria (Furustrand Tafin et al. 2011). The accurate measuring temperature controlled at ±0.0001 °C allows an analytical sensitivity of ±0.2 μW, but in this study the experimental detection limit was determined at 10 μW to distinguish microbial heat production from the thermal background (e.g. non-specific heat flow generated by degradation of the growth medium). Time to detection was defined as the duration of a microcalorimetry experiment to reach 10 μW, and was therefore not equivalent to the earliest sign of increase in heat flow. TTD is inversely proportional to the initial quantity and growth rate of bacteria, and we cannot exclude the possibility that discrete metabolism in viable but non-cultivable bacteria is neglected because of this detection limit.

In conclusion, biofilm bacteria are less susceptible to antibiotics than their non-adherent, planktonic counterparts. Weak growth inhibition was demonstrated with the time-dependent antibiotics (vancomycin and flucloxacillin), whereas the concentration-dependent drugs daptomycin and ciprofloxacin considerably reduced the ability to detect biofilm bacteria. These findings appear to support a recommendation of thorough surgical debridement in order to reduce the bacterial load rather attempts to cure an implant-related deep infection with antimicrobial therapy (Zimmerli et al. 2004).

Seen from a diagnostic point of view, these results might also indicate that preoperative administration of antibiotics has heterogeneous effects on the ability to detect biofilm bacteria. The quantitative and highly reproducible outcome of these procedures calls for further research in diagnosis and treatment of implant-related infections.

All the authors contributed to writing of the protocol. The laboratory work was mainly conducted by CR, with help from UFT and BB. CR and AT wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all the authors revised it and approved the final version.

We thank Assistant Professor Birgit Debrabant and senior statistician Donatien Tafin Djoko for statistical advice. We are grateful to the Regional Foundation of Southern Denmark and the Danish Rheumatism Association for financial support.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Achermann Y, Vogt M, Leunig M, Wust J, Trampuz A.. Improved diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection by multiplex PCR of sonication fluid from removed implants. J Clin Microbiol 2010; 48 (4): 1208–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asin E, Isla A, Canut A, Rodriguez Gascon A.. Comparison of antimicrobial pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic breakpoints with EUCAST and CLSI clinical breakpoints for Gram-positive bacteria. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2012; 40 (4): 313–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berbari E F, Marculescu C, Sia I, Lahr B D, Hanssen A D, Steckelberg J M, Gullerud R, Osmon D R.. Culture-negative prosthetic joint infection. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45 (9): 1113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boling E A, Blanchard G C, Russell W J.. Bacterial identification by microcalorimetry. Nature 1973; 241 (5390): 472–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borens O, Yusuf E, Steinrucken J, Trampuz A.. Accurate and early diagnosis of orthopedic device-related infection by microbial heat production and sonication. J Orthop Res 2013; 31 (11): 1700–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss M, Trampuz A, Borens O, Bohner M, Ilchmann T.. Biofilm formation on bone grafts and bone graft substitutes: comparison of different materials by a standard in vitro test and microcalorimetry. Acta Biomater 2010; 6 (9): 3791–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that growth aerobically In: Approved standard-ninth edition CLSI document M07-A9 Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that growth aerobically. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Corvec S, Furustrand Tafin U, Betrisey B, Borens O, Trampuz A.. Activities of fosfomycin, tigecycline, colistin, and gentamicin against extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in a foreign-body infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57 (3): 1421–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costerton J W. Biofilm theory can guide the treatment of device-related orthopaedic infections. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005; (437): 7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costerton J W, Stewart P S, Greenberg E P.. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 1999; 284 (5418): 1318–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale H, Fenstad A M, Hallan G, Havelin L I, Furnes O, Overgaard S, Pedersen A B, Karrholm J, Garellick G, Pulkkinen P, Eskelinen A, Makela K, Engesaeter L B.. Increasing risk of prosthetic joint infection after total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (5): 449–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furustrand Tafin U, Majic I, Zalila Belkhodja C, Betrisey B, Corvec S, Zimmerli W, Trampuz A.. Gentamicin improves the activities of daptomycin and vancomycin against Enterococcus faecalis in vitro and in an experimental foreign-body infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55 (10): 4821–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furustrand Tafin U, Clauss M, Hauser P M, Bille J, Meis J F, Trampuz A.. Isothermal microcalorimetry: a novel method for real-time determination of antifungal susceptibility of Aspergillus species. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012a; 18 (7): E241–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furustrand Tafin U, Corvec S, Betrisey B, Zimmerli W, Trampuz A.. Role of rifampin against Propionibacterium acnes biofilm in vitro and in an experimental foreign-body infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012b; 56 (4): 1885–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gbejuade H O, Lovering A M, Webb J C.. The role of microbial biofilms in prosthetic joint infections. Acta Orthop 2014: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundtoft P H, Overgaard S, Schonheyder H C, Moller J K, Kjaersgaard-Andersen P, Pedersen A B.. The "true" incidence of surgically treated deep prosthetic joint infection after 32,896 primary total hip arthroplasties. Acta Orthop 2015: 86(3): 326–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huotari K, Lyytikainen O, Ollgren J, Virtanen M J, Seitsalo S, Palonen R, Rantanen P, Hospital Infection Surveillance T. Disease burden of prosthetic joint infections after hip and knee joint replacement in Finland during 1999-2004: capture-recapture estimation. J Hosp Infect 2010; 75 (3): 205–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamme C, Lindberg L.. Aerobic and anaerobic bacteria in deep infections after total hip arthroplasty: differential diagnosis between infectious and non-infectious loosening. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1981; (154): 201–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S M, Lau E, Watson H, Schmier J K, Parvizi J.. Economic burden of periprosthetic joint infection in the United States. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27 (8 Suppl): 61–5 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiolo E M, Furustrand Tafin U, Borens O, Trampuz A.. Activities of fluconazole, caspofungin, anidulafungin, and amphotericin B on planktonic and biofilm Candida species determined by microcalorimetry. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58 (5): 2709–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malekzadeh D, Osmon D R, Lahr B D, Hanssen A D, Berbari E F.. Prior use of antimicrobial therapy is a risk factor for culture-negative prosthetic joint infection. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468 (8): 2039–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihailescu R, Furustrand Tafin U, Corvec S, Oliva A, Betrisey B, Borens O, Trampuz A.. High activity of Fosfomycin and Rifampin against methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus biofilm in vitro and in an experimental foreign-body infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58 (5): 2547–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Manso D, del Prado G, Ortiz-Perez A, Manrubia-Cobo M, Gomez-Barrena E, Cordero-Ampuero J, Esteban J.. In vitro susceptibility to antibiotics of staphylococci in biofilms isolated from orthopaedic infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2013; 41 (6): 521–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monzon M, Oteiza C, Leiva J, Lamata M, Amorena B.. Biofilm testing of Staphylococcus epidermidis clinical isolates: low performance of vancomycin in relation to other antibiotics. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2002; 44 (4): 319–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangehl M J, Masri B A, O’Connell J X, Duncan C P.. Prospective analysis of preoperative and intraoperative investigations for the diagnosis of infection at the sites of two hundred and two revision total hip arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1999; 81 (5): 672–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefansdottir A, Johansson D, Knutson K, Lidgren L, Robertsson O.. Microbiology of the infected knee arthroplasty: report from the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register on 426 surgically revised cases. Scand J Infect Dis 2009; 41 (11-12): 831–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetreault M W, Wetters N G, Aggarwal V, Mont M, Parvizi J, Della Valle C J.. The Chitranjan Ranawat Award: Should prophylactic antibiotics be withheld before revision surgery to obtain appropriate cultures? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472 (1): 52–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trampuz A, Hanssen A D, Osmon D R, Mandrekar J, Steckelberg J M, Patel R.. Synovial fluid leukocyte count and differential for the diagnosis of prosthetic knee infection. Am J Med 2004; 117 (8): 556–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trampuz A, Piper K E, Jacobson M J, Hanssen A D, Unni K K, Osmon D R, Mandrekar J N, Cockerill F R, Steckelberg J M, Greenleaf J F, Patel R.. Sonication of removed hip and knee prostheses for diagnosis of infection. N Engl J Med 2007a; 357 (7): 654–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trampuz A, Salzmann S, Antheaume J, Daniels A U.. Microcalorimetry: a novel method for detection of microbial contamination in platelet products. Transfusion 2007b; 47 (9): 1643–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Ah U, Wirz D, Daniels A U.. Rapid differentiation of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus from methicillin-resistant S. aureus and MIC determinations by isothermal microcalorimetry. J Clin Microbiol 2008; 46 (6): 2083–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zappe B, Graf S, Ochsner P E, Zimmerli W, Sendi P.. Propionibacterium spp. in prosthetic joint infections: a diagnostic challenge. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2008; 128 (10): 1039–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli W, Moser C.. Pathogenesis and treatment concepts of orthopaedic biofilm infections. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2012; 65 (2): 158–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner P E.. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med 2004; 351 (16): 1645–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]