Abstract

Alcohol use is common among people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). In this narrative review, we describe literature regarding alcohol’s impact on transmission, care, co-infections and comorbidities that are common among people living with HIV (PLWH), as well as literature regarding interventions to address alcohol use and its influences among PLWH. This narrative review identifies alcohol use as a risk factor for HIV transmission, as well as a factor impacting the clinical manifestations and management of HIV. Alcohol use appears to have additive and potentially synergistic effects on common HIV-related comorbidities. We find that interventions to modify drinking and improve HIV-related risks and outcomes have had limited success to date, and we recommend research in several areas. Consistent with Office of AIDS Research/National Institutes of Health priorities, we suggest research to better understand how and at what levels alcohol influences comorbid conditions among PLWH, to elucidate the mechanisms by which alcohol use is impacting comorbidities, and to understand whether decreases in alcohol use improve HIV-relevant outcomes. This should include studies regarding whether state-of-the-art medications used to treat common co-infections are safe for PLWH who drink alcohol. We recommend that future research among PLWH include validated self-report measures of alcohol use and/or biological measurements, ideally both. Additionally, subgroup variation in associations should be identified to ensure that the risks of particularly vulnerable populations are understood. This body of research should serve as a foundation for a next generation of intervention studies to address alcohol use from transmission to treatment of HIV. Intervention studies should inform implementation efforts to improve provision of alcohol-related interventions and treatments for PLWH in healthcare settings. By making further progress on understanding how alcohol use affects PLWH in the era of HIV as a chronic condition, this research should inform how we can mitigate transmission, achieve viral suppression, avoid exacerbating common comorbidities of HIV and alcohol use and make progress toward the 90-90-90 goals for engagement in the HIV treatment cascade.

Keywords: alcohol, alcohol use, substance use, HIV, HIV-related comorbidities

INTRODUCTION

Both human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and alcohol use are common worldwide (UNAIDS, 2015). In some cases, such as Russia and Uganda, high per capita alcohol use overlaps with a high prevalence of HIV (Rehm et al., 2006; Rehm et al., 2009a). In the U.S., approximately 1.1 million people are living with HIV (PLWH) (Hall et al., 2009; Lansky et al., 2010; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012), and 88% of adults report any past-year alcohol use (≥1 drink), 25% report past-month heavy drinking (≥5 drinks on ≥ 1days), and 14% meet criteria for a past-year alcohol use disorder (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014; Grant et al., 2015).

A substantial proportion of PLWH consume alcohol, many at unhealthy levels (heavy drinking and/or alcohol use disorder) (Saitz, 2005). The prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use in PLWH ranges from 8% (Galvan et al., 2002) to 42% (Samet et al., 2004b; Lefevre et al., 1995). Based on data from the U.S. general population, sub-populations at high risk of having both HIV and unhealthy alcohol use include men who have sex with men (MSM), racial/ethnic minorities, persons who inject drugs, sex workers, and persons of low socioeconomic status (Hall et al., 2009; Lansky et al., 2010; Pellowski et al., 2013; Delker et al., 2016).

In this narrative review, we describe literature regarding alcohol’s impact on HIV acquisition/transmission, care, co-infections and comorbidities common among PLWH, and morbidity and mortality, as well as literature regarding interventions to address alcohol use and its influences among PLWH.

Alcohol Use and Risk Behaviors for HIV Acquisition/Transmission

Alcohol use has a strong and consistent association with HIV incidence (Shuper et al., 2010; Scott-Sheldon et al., 2016). Associations between alcohol use and sex-risk behaviors have been identified consistently (Shuper et al., 2009; Samet et al., 2007b; Maisto and Simons, 2016; Maisto et al., 2012). A meta-analysis of 30 experimental studies found that participants randomly assigned to consume alcohol reported stronger intentions to engage in unprotected sex, weaker sexual communication and negotiation skills, and higher levels of sexual arousal than participants assigned to either placebo or no-alcohol control groups (Scott-Sheldon et al., 2016), suggesting a causal link between alcohol use and sexual risk taking (and thus HIV transmission).

Several studies have tested interventions focused either on reducing HIV risk among people who drink or on reducing alcohol use to reduce HIV transmission (Carrasco et al., 2016; Samet and Walley, 2010; Eaton et al., 2013; Kalichman et al., 2008; Samet et al., 2015; Samet et al., 2008; Monti et al., 2016; Kennedy et al., 2016) with limited success, especially with regards to sustained effects across multiple domains (e.g., reductions of both alcohol and sex-risk behaviors). A review of interventions tested in sub-Saharan Africa suggested a need for interventions that address alcohol use and HIV risk both at individual and policy levels (Carrasco et al., 2016).

Alcohol Use and the HIV Treatment Cascade

The HIV treatment cascade identifies five stages of HIV medical care—1) diagnosis, 2) linkage to medical care, 3) engagement with/retention in medical care, 4) treatment with antiretroviral therapy (ART), and 5) achievement of viral suppression—all considered essential targets to meet in order to effectively treat and prevent the spread of HIV (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2014; Skarbinski et al., 2015; Mugavero et al., 2013; Bor et al., 2015; Cohen et al., 2014; Park et al., 2007). World Health Organization (WHO) goals for 2020 are the achievement of 90-90-90 with regard to percent identification, engagement with ART initiation, and viral suppression (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2014)

Alcohol use has been shown to influence HIV care and outcomes at every stage of the cascade (Azar et al., 2010b; Vagenas et al., 2015); it is associated with lower receipt of HIV testing (Fatch et al., 2013; Vagenas et al., 2014; Bengtson et al., 2014), greater delay in engaging with medical care after testing positive (Samet et al., 1998), delay in, lower quality of, and worse retention in HIV treatment (Samet et al., 2001; Korthuis et al., 2012; Cunningham et al., 2006; Giordano et al., 2005; Samet et al., 2003; Monroe et al., 2016), and non-adherence to ART (Hendershot et al., 2009). Some studies have also identified associations between alcohol use and disease progression (see below) (Hahn and Samet, 2010). The high prevalence of alcohol use and the fact it is often unaddressed likely combine to result in suboptimal engagement. Reducing alcohol use may be fertile ground for interventions aimed at meeting WHO goals.

Alcohol and Treatment with ART—Adherence

The association between alcohol use and non-adherence to ART has received substantial attention regarding alcohol’s role in the HIV treatment cascade (Hendershot et al., 2009). Some studies reveal any (versus no) alcohol use is associated with non-adherence (Hendershot et al., 2009; Samet et al., 2004a). Other studies have found threshold effects of heavy drinking (Samet et al., 2004a) or dose response relationships between the amount consumed and the number of pills missed (Braithwaite et al., 2005; Parsons et al., 2008). The association between alcohol use and non-adherence is thought to reflect both failure to take medications as a result of complex dosing regimens and intoxication due to heavy drinking episodes, as well as intentional missed doses due to beliefs regarding potential toxic interactions between ART and alcohol (Kalichman et al., 2013a; Kalichman et al., 2013b; Parsons et al., 2007b; Pellowski et al., 2016). The extent to which alcohol and ART have toxic interactions and at what levels remains unclear, though potential biological mechanisms by which toxicity may exist have been described (Kumar et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2015; McCance-Katz et al., 2013)and one recent study identified potential interactive effects on liver disease (Bilal et al., 2016).

At least two studies have tested interventions aimed at simultaneously reducing alcohol use and improving ART adherence (Samet and Walley, 2010). One tested a nurse-led multi-component intervention that included 4 visits over 3 months, which had no effect on alcohol use or ART adherence (Samet et al., 2005). The other tested eight 1-hour individual sessions of motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral skills over 3 months; positive intervention effects on self-reported medication adherence and markers of disease progression were observed at 3 months, but not sustained (Parsons et al., 2007a). Given the substantial influence of this modifiable risk factor on this key treatment goal, further research is warranted regarding how to influence ART adherence via reducing drinking, or in the context of continued drinking.

Alcohol and Achievement of Viral Suppression—Disease Progression

While multiple studies have identified associations between alcohol use and HIV disease progression, the extent to which alcohol use directly affects disease progression is not fully resolved (Hahn and Samet, 2010; Azar et al., 2010a). Identified associations may be mediated by behavioral mechanisms—the most common being non-adherence to ART—or they may be direct, resulting from biological mechanisms (Hahn and Samet, 2010).

Several plausible biological mechanisms may account for how alcohol may increase pre-ART HIV disease progression. Both HIV and alcohol are established causes of microbial translocation and systemic inflammation (Thurman, 1998; Brenchley et al., 2006; Douek, 2007), and both induce immune activation. Therefore, it is plausible that alcohol may accelerate the progression of HIV disease via these pathways. Alcohol use may contribute to T cell proliferative defects (Szabo et al., 2004). And both HIV and alcohol cause a similar disruption of the normal gut microbiome, which may contribute to systemic immune activation by either impairing gut barrier integrity or absorption of bacteria-derived metabolites that confer immune defects (Dillon et al., 2014). Markers of microbial translocation are associated with increased opportunistic co-infections (Cassol et al., 2010), HIV disease progression (Marchetti et al., 2008; Balagopal et al., 2008), and mortality (Sandler et al., 2010). The link between alcohol use and markers of microbial translocation in PLWH has been examined to a limited extent, and findings have been mixed (Monnig et al., 2016; Hunt et al., 2014; Cioe et al., 2015; Balagopal et al., 2008; Carrico et al., 2015). Experimental studies of the effect of alcohol on progression of the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) in macaques largely support the biologic plausibility of alcohol’s influence on disease progression (Amedee et al., 2014; Marcondes et al., 2008; Kumar et al., 2005; Bagby et al., 2006; Poonia et al., 2006; Molina et al., 2006). However, the most recent study, which randomized macaques to chronic heavy drinking (versus sucrose) and subsequently to ART (versus no ART), identified no association between chronic heavy drinking and viral load over 4 months, regardless of ART status (Molina et al., 2014a).

The results of human observational studies have been mixed, perhaps because of factors that can affect disease progression in people outside of tightly controlled experimental settings (Hahn and Samet, 2010). Of the several prospective studies conducted in the pre-highly active ART era (Kaslow et al., 1989; Penkower et al., 1995; Eskild and Petersen, 1994; Tang et al., 1997; Veugelers et al., 1994; Webber et al., 1999; Chandiwana et al., 1999), none found an association between alcohol consumption and the onset of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). In the highly-active ART era, after controlling for ART use, four prospective studies found no association between heavy drinking and HIV disease progression, as measured by CD4 cell count or HIV viral load (Ghebremichael et al., 2009; Cook et al., 2008; Chander et al., 2006b; Kowalski et al., 2012), and one identified an increased risk of virological failure associated with heavy alcohol use (Deiss et al., 2016). Two earlier prospective studies that separately examined HIV disease progression among those not on ART found that heavy alcohol consumption was associated with lower CD4 cell count (Samet et al., 2007a) and shorter time to CD4 cell count <200 cells/mm3 (Baum et al., 2010), but not differences in HIV viral load (Samet et al., 2007a; Baum et al., 2010). These studies both had small samples of persons not on ART (n=128 and n=87 respectively). A 7-year study among 5,067 Swiss PLWH, which stratified analyses by ART naïve and individuals initiating ART, found no association between alcohol use and virological failure or CD4 cell counts over time in either group (Conen et al., 2013). Findings to date suggest the possibility that alcohol use may not directly influence disease progression. However, further research is needed to explore longer term outcomes associated with heavy drinking in macaques, as well as influences of alcohol use on disease progression among larger samples of PLWH and among untreated PLWH.

Alcohol Use and HIV-Associated Comorbidities

Medical illnesses associated with alcohol use often seen in older adults without HIV infection (Cherpitel et al., 2015) are now occurring as common comorbid conditions in younger PLWH despite prolonged viral suppression (Crothers et al., 2009; Hasse et al., 2011; Simmons et al., 2013; Guaraldi et al., 2011; Sharma et al., 2015; Shiau et al., 2013; Hansen et al., 2012), which may reflect premature aging (High et al., 2012; Justice and Falutz, 2014). In addition to the direct, toxic pathophysiologic effects of both HIV and alcohol, mechanisms that are likely to lead to high rates of comorbid conditions among PLWH include immune senescence (the effects of aging on the function of the immune system), inflammation, and hypercoagulability (High et al., 2012; Deeks, 2009; Deeks, 2011; Katz et al., 2015). Because alcohol use impacts some of these same mechanisms, there has been investigation of the role of alcohol use in HIV-related comorbidities (Neuman et al., 2012; Bryant et al., 2010; Freiberg et al., 2010; Sarkar et al., 2015; World Health Organization, 2015), and the study of comorbidities is now a high priority for NIH (National Institutes of Health, 2015). We review research to date on HIV-associated comorbidities in which alcohol may play a role.

Common Co-Infections

Hepatitis C and Tuberculosis

Approximately 25 – 30% of PLWH are co-infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) (Alter, 2006; Platt et al., 2016). Chronic HCV infection is a major cause of morbidity and mortality among PLWH (Sulkowski, 2013). PLWH with HCV co-infection have accelerated progression of HCV-related liver disease (i.e., cirrhosis and liver cancer) (Sulkowski, 2007a; Sulkowski, 2007b; Sulkowski, 2008). Although little is known about how low-level drinking influences HCV outcomes, abstinence from alcohol use is recommended for PLWH with HCV co-infection (Tsui et al., 2013) because liver disease outcomes are also adversely impacted by alcohol use (Peters and Terrault, 2002; Morgan et al., 2003; Sulkowski, 2007a; Sulkowski, 2007b; Sulkowski, 2008; Cooper and Cameron, 2005; Safdar and Schiff, 2004; Schiff and Ozden, 2003; Fuster et al., 2014; Fuster et al., 2013; Tsui et al., 2013; Tsui et al., 2006).

Similarly, both alcohol use and HIV are associated with increased risk of tuberculosis (TB) infection (Lonnroth et al., 2008; Rehm et al., 2009b), which is the leading cause of mortality in PLWH worldwide (World Health Organization, 2014; UNAIDS, 2015). Alcohol use (any versus none) is associated with an increased risk (up to 3-fold) of having active TB and poorer TB outcomes (Volkmann et al., 2016), likely as a result of alcohol’s impact on the immune system, poor TB treatment adherence, and social marginalization that increases risk for infection (Rehm et al., 2009b), all of which may be amplified among PLWH given potential overlapping mechanisms.

Alcohol use is relevant to each of these common co-infections not only due to its potential to speed their progression but also because it likely influences their care. Alcohol use was a contraindication to previously used treatments for HCV, and the WHO warns against the use of isoniazid preventive therapy—commonly used to prevent mortality and active TB among PLWH—in persons with “regular and heavy alcohol use”(World Health Organization, 2011). While the WHO recommendation was made based on prior reports of isoniazid toxicity among heavy drinkers, no studies have systematically assessed the safety of TB preventive therapy in heavy drinkers with or without HIV infection. Moreover, it is unknown whether emerging treatments for HCV—directly acting antivirals that are highly effective in HIV co-infected patients (Sulkowski, 2013)—have contraindications for persons who drink. This is a rapidly evolving story for both co-infections; studies are needed to assess whether alcohol use is associated with poor outcomes among PLWH who are treated for HCV or TB infection. In the meantime, historical contraindications and current WHO recommendations are likely to influence clinical decision making regarding provision of recommended treatments. Given that alcohol use is an established risk factor for decreased ART adherence (Hendershot et al., 2009) and data suggest risk for active TB treatment discontinuation (Kendall et al., 2013), it will also be important to assess alcohol’s influence on adherence to and completion of treatments for both co-infections, as well as to identify interventions that may support reduced drinking and treatment adherence.

Cardiovascular Diseases

PLWH who drink heavily and/or meet criteria for alcohol use disorders are at increased risk for coronary heart disease (CHD) and other cardiovascular diseases (CVD) (Freiberg et al., 2013; Freiberg et al., 2010). In one study heavy drinking was a risk factor for CHD among PLWH but not those without HIV (Freiberg et al., 2010). Mechanisms underlying CHD risk among PLWH are unclear but have been linked to inflammation (Niaura et al., 2000; Armah et al., 2012). ART and HIV viral suppression do not eliminate the increased risk of CHD (Freiberg et al., 2013), nor does ART return increased inflammation to pre-HIV infection levels (Freiberg et al., 2015). A systematic review of 13 studies suggests an increased risk of CVD associated with any and heavy alcohol use among PLWH ranging from 37% (95% CI: 2% – 84%) to 78% (95% CI: 9% – 293%) (Kelso et al., 2015). While it is clear that alcohol increases risk for CVD among PLWH, alcohol’s role in CVD risk merits further inquiry. For instance, the levels of alcohol use at which CVD risk is increased for PLWH are unclear: most studies have not compared non-drinking to low-level or “moderate” drinking, but one large observational study that did identified a protective effect of low-level drinking (Carrieri et al., 2012). In addition, while cardiomyopathy is a condition for which both alcohol and HIV can be underlying etiologies, the additive or synergistic impact of these combined exposures for this pathology has not been delineated.

Cancers

Rates of non-AIDS-defining cancer deaths are increasing among PLWH (Smith et al., 2014) and contributing an ever-greater health burden (Deeken et al., 2012; Shiels et al., 2011; Cutrell and Bedimo, 2013). Relative to uninfected persons, PLWH are at higher risk for many cancers, likely due to a combination of the direct toxic effects of the HIV virus, as well as chronic inflammation and immune suppression/activation, and high rates of co-infections and risk factors, such as smoking (Cutrell and Bedimo, 2013; Sigel et al., 2012; Bedimo et al., 2009; Borges et al., 2014; McGinnis et al., 2006; Park et al., 2016). Alcohol use may be another risk factor. Mechanisms by which rates of cancer may be elevated among PLWH (e.g., immune system effects, inflammation, and co-occurrence with other risk factors) overlap with mechanisms by which alcohol use adversely influences cancer outcomes. However, the specific role of alcohol use in cancer risk among PLWH is unknown (D’Souza et al., 2014). Alcohol use is a risk factor for liver and head and neck cancers among PLWH (McGinnis et al., 2006; Freedman et al., 2007; Viswanathan and Wilson, 2004), and findings from one study suggest that, together, alcohol use and HCV accounted for increased risk of liver cancer, but not non-Hodgkins lymphoma, among PLWH (McGinnis et al., 2006). Findings to date suggest alcohol’s influence on cancers among PLWH is likely complex; alcohol may be a stronger contributor to some cancers than others and may have additive or synergistic effects on cancer-related outcomes.

Neurological Disorders

The severity of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) (Antinori et al., 2007) has declined in the post-ART era, but PLWH continue to face an array of neurological problems (Sacktor et al., 2016; Heaton et al., 2011; Heaton et al., 2010; Elbirt et al., 2015; Harezlak et al., 2011). Alcohol use disorders are a known risk factor for neurocognitive dysfunction and are linked to impaired memory and decision making (Anand et al., 2010; Loeber et al., 2009). Alcohol use and HIV may have combined effects on neurocognitive decline (Anand et al., 2010; Persidsky et al., 2011; Thaler et al., 2015). However, the findings of studies assessing this question have been mixed. Some suggest that alcohol and HIV have additive adverse effects (Rothlind et al., 2005; Green et al., 2004), while a cross-sectional study of HIV-infected alcohol users found lower than average neurocognitive scores, but no significant relationship between number of heavy drinking days and neurocognitive performance (Attonito et al., 2014; Attonito, 2013). The interplay of alcohol and neurocognitive decline among PLWH merits further research.

Other related issues are also in need of further investigation. For instance, pain is common and associated with unhealthy alcohol use among PLWH (Merlin, 2015; Merlin et al., 2012a; Tsui et al., 2014). Because pain itself may interrupt engagement in HIV care (Berg et al., 2009; Merlin et al., 2012b) and may also induce alcohol use as a coping mechanism (Tsui et al., 2014), alcohol’s role in pain management among PLWH, is an area ripe for further study. Another issue in need of further investigation is alcohol’s role in neuropathy among PLWH. While both HIV and HIV treatments have known associations with neuropathy (Amruth et al., 2014), the role in these associations of a known etiology of peripheral neuropathy, alcohol use, has not been described.

Metabolic Complications

PLWH experience metabolic complications, which increase the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Crum-Cianflone et al., 2010; Crum-Cianflone et al., 2008; Samaras, 2012; Samaras et al., 2007; Calvo and Martinez, 2014). PLWH frequently gain weight following ART initiation (Lakey et al., 2013; Justice and Falutz, 2014). The prevalence of metabolic complications and diabetes is higher among PLWH than among those without HIV and is generally linked to lipid imbalances resulting from ART and chronic low-grade inflammation from HIV (Paula et al., 2013; Samaras et al., 2007; Jacobson et al., 2006; Mozumdar and Liguori, 2011; Rasmussen et al., 2012; De Wit et al., 2008). Alcohol use is associated with diabetes (Howard et al., 2004) and metabolic derangements consistent with lipodystrophy (Cheng et al., 2009). Alcohol use has also been linked to oxidative stress on muscles, bones and adipose tissue, and is thought to exacerbate lipid imbalances from HIV (Molina et al., 2014b). However, among PLWH and those without HIV, associations with alcohol use and both diabetes and metabolic syndrome appear to be U-shaped such that “moderate” alcohol use may be protective, whereas heavy drinking increases risk (Howard et al., 2004; Butt et al., 2009; Samaras et al., 2007; Tiozzo et al., 2015; Freiberg et al., 2004; Sidorenkov et al., 2010; Wakabayashi, 2014; Athyros et al., 2007). Research is needed regarding the potentially complex ways in which alcohol use influences metabolic complications among PLWH.

Falls and Injury

Up to 30% of PLWH experience falls annually (Erlandson et al., 2012). Falls can lead to fractures, which are 40–60% more common in PLWH relative to those without HIV (Sharma et al., 2015; Shiau et al., 2013; Hansen et al., 2012), likely as a result of both high-energy injuries and fragility. Alcohol use is a potent risk factor for falls and fractures (Cherpitel et al., 2015; Cawthon et al., 2006; Kanis et al., 2004; Berg et al., 2008; Mukamal et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2014) and it can also exacerbate inflammation, which could influence complications related to recovery from falls and fractures. Further research on the association between alcohol use and falls and injury among PLWH is needed, as is investigation of the role of alcohol reduction in fall prevention among PLWH.

Other Substance Use

More than 42% of PLWH in the US smoke (with some studies reporting 46–84%), compared with less than 20% of the general population (Lifson and Lando, 2012; Lifson et al., 2010; Mdodo et al., 2015; Marshall et al., 2009; Cooperman, 2016). Among PLWH, smoking is associated with increased risk for bacterial pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), coronary heart disease (CHD) and its associated complications, and decreased bone mineral density (Lifson et al., 2010; Cooperman, 2016). Though evidence is mixed (Kabali et al., 2011; Marshall et al., 2009), smoking may also be associated with HIV disease progression (Hile et al., 2016). Smoking is more strongly associated with poor health outcomes among PLWH than among those without HIV (Crothers et al., 2009; Crothers et al., 2005) and is likely an important contributor to the substantial comorbidity experienced by PLWH (Marshall et al., 2009). Smoking and alcohol use are correlated with one another in PLWH (Braithwaite et al., 2016) and, due to the potential for additive inflammatory effects of alcohol use and smoking (Niaura et al., 2000; Armah et al., 2012), PLWH who both smoke and drink alcohol may be at greater risk for adverse health outcomes, such as CHD and pneumonia. Despite the potential syndemic effects and the common co-occurrence of smoking and alcohol use among PLWH (Braithwaite et al., 2016), little research has investigated the synergistic effects of alcohol and tobacco use among PLWH, and interventions to improve both among PLWH.

Similarly, other drug use is common among PLWH (Green et al., 2010; Bing et al., 2001; Korthuis et al., 2012; Mathers et al., 2008) and often co-occurs with alcohol use (Green et al., 2010; Walley et al., 2008; Van Tieu and Koblin, 2009). This combination is likely to increase risk for multiple adverse outcomes. Given that drug use is associated with poorer engagement with the HIV treatment cascade, including medication adherence (Peretti-Watel et al., 2006; Mugavero et al., 2006), co-occurring alcohol and drug use may additively or synergistically adversely influence engagement with HIV care. Further, co-occurring alcohol and drug use may exacerbate severity of comorbid conditions, such as neurological function (Meyer et al., 2013; Weber et al., 2013; Hauser and Knapp, 2014), and outcomes of common co-infections among PLWH, which, in some cases, are disproportionately distributed among people who use drugs. For instance, an estimated 82% of people who inject drugs with HIV have HCV (Platt et al., 2016). Finally, alcohol use may enhance risk for drug overdose (Coffin et al., 2007; Shah et al., 2008; Coffin et al., 2003; Riley et al., 2016). Because similar levels of alcohol consumption may have greater effects for PLWH compared to those without HIV (McGinnis et al., 2016; Justice et al., 2016; McCance-Katz et al., 2012), alcohol’s influence on overdose may be enhanced among PLWH. Research is needed to more comprehensively understand the clustering of risks among PLWH and the combined effects of these risk profiles on adverse outcomes.

Mental Health Disorders

In addition to other substance use, mental health disorders, including depression, anxiety, trauma, and, stress are common among PLWH (Sullivan et al., 2011; Sullivan et al., 2008; Chander et al., 2006a; Walkup et al., 2008; Braithwaite et al., 2016). The majority of research to date on alcohol use and mental health conditions among PLWH has focused on depression. Both alcohol use and depression are associated with reduced engagement with the HIV treatment cascade and adverse HIV-related consequences (Cruess et al., 2005; Cruess et al., 2003; Evans et al., 2002; Leserman, 2003; Leserman, 2008; Leserman et al., 2008; Ghebremichael et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2007; Goodness et al., 2014). Unhealthy (relative to low-risk) alcohol use is associated with higher risk of depressive symptoms (Sullivan et al., 2011), and longitudinal research among PLWH suggests that this association is uni-directional, such that alcohol use precedes depressive symptoms (Fergusson et al., 2009). Moreover, changes in drinking appeared to result in concomitant changes in depressive symptoms such that PLWH who switch to higher or lower level drinking experience a similar alteration in their depressive symptoms (Sullivan et al., 2011). While the association between alcohol use and depression appears to be similar for people with and without HIV (Sullivan et al., 2011), the common co-occurrence of these conditions and both of their influences on poor HIV-related outcomes is likely to have at least an additive effect on PLWH. Psychological trauma, stress, and anxiety, which often co-occur with heavy alcohol use (Pence et al., 2008), are associated with adverse HIV-related outcomes (Chander et al., 2006a; Leserman, 2003; Leserman, 2008; Leserman et al., 2008; Machtinger et al., 2012 ; Liebschutz et al., 2000). Research is needed to understand the potential synergistic effects of alcohol use with these common mental health conditions among PLWH, including investigation of issues related to temporality, mechanisms, prevention, and treatment in the context of co-occurring alcohol use and mental health conditions (Chander et al., 2006a). Finally, research on associations between alcohol use and co-occurring serious mental illness among PLWH is needed.

Morbidity and Mortality

While mortality rates among PLWH have declined (Simmons et al., 2013; Hasse et al., 2011), PLWH are still at higher risk for mortality, as well as physiological frailty, relative to those without HIV (Justice and Falutz, 2014). Alcohol use is associated with increased risk of mortality in general samples (Kinder et al., 2009; Rehm et al., 2001; Rehm et al., 2003), as well as specifically among PLWH (Neblett et al., 2011; Wandeler et al., 2016; Justice et al., 2016). While most large observational studies, including one among PLWH (Wandeler et al., 2016), have identified a J-shaped association between alcohol use and all-cause mortality (with a protective effect of low-level or “moderate” drinking), a recent meta-analysis (not HIV-specific) of 87 studies including over 3 million people, which adjusted for study design characteristics known to bias results, found no protective effect of low-level drinking (Stockwell et al., 2016). A recent study demonstrated an association between alcohol use and both physiological frailty and mortality among PLWH but did not include a non-drinker group, and thus was not able to assess the effects of low-level or “moderate” drinking on morbidity and mortality (Justice et al., 2016). However, this study’s findings suggested that PLWH experienced risk at lower levels of alcohol use relative to uninfected individuals (>30 drinks per month for PLWH versus >70 drinks per month for those without HIV for mortality) (Justice et al., 2016). These findings are aligned with previous research, which has identified greater blood alcohol concentration (McCance-Katz et al., 2012) and increased likelihood of feeling “a buzz” (McGinnis et al., 2016) at similar levels of drinking for PLWH relative to those without HIV. Together these findings suggest the possibility that alcohol’s influence on health is greater among PLWH than it is among uninfected populations and further highlight the need to gain clarity and precision regarding how and at what levels alcohol use influences health among PLWH, as well as underlying mechanisms.

HIV and Alcohol in a Social Context, Intersectionality, and Potential Subgroup Variation

Both HIV and alcohol use are stigmatized conditions about which discrimination is common. Therefore, the social and environmental contexts in which PLWH who drink live is likely to influence outcomes (Stokols, 1992). Moreover, both alcohol use and HIV disproportionately impact vulnerable populations, including people living in poverty and poor resource settings, those who experience multiple forms of social disadvantage, racial/ethnic minorities, and MSM (Grant et al., 2015; Hall et al., 2009; Lansky et al., 2010; Mulia et al., 2009; Pellowski et al., 2013). Many of these characteristics overlap within individuals (e.g., racial/ethnic minorities disproportionately live in poor resource settings). Intersectionality theory and syndemic perspectives (Kelly, 2009; Talman et al., 2013; Pellowski et al., 2013) suggest that the chronic psychosocial stresses observed over the life course for these populations are likely to synergistically influence health over time and, thus, may result in health disparities. Research should investigate subgroup variation resulting from lived experiences in associations between alcohol use and HIV-related outcomes, to ensure risks specific to vulnerable populations are understood.

Addressing/Reducing Alcohol Use among PLWH

Despite its substantial burden on HIV and related illnesses, alcohol use is often overlooked in HIV care (Metsch et al., 2008; Conigliaro et al., 2003; Chander et al., 2016; Korthuis et al., 2008 ; Korthuis et al., 2011; Strauss et al., 2009a; Strauss et al., 2012). Research suggests substantial barriers to HIV care providers’ addressing alcohol use with their patients (Strauss et al., 2009a; Strauss et al., 2009b). Both PLWH and HIV care providers perceive alcohol use as a low priority for HIV clinical care relative to other domains of care (Fredericksen et al., 2015).

Efforts to describe and address deficiencies in alcohol-related care among PLWH are occurring in several domains. First, ongoing health services research is being conducted to assess whether, in healthcare settings in which alcohol-related care is common (e.g., the Veterans Health Administration), differences in receipt of alcohol-related care exist across HIV status (Williams and Bradley, 2015). Studies are also underway to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of alcohol treatments among PLWH (Kraemer, 2013). Second, several studies of alcohol-related interventions have been tested among PLWH with unhealthy alcohol use (Papas et al., 2011; Samet et al., 2015; Hasin et al., 2013; Samet and Walley, 2010; Chander et al., 2015; World Health Organization, 2011), and others have been piloted (Edelman et al., 2012) or are ongoing (Edelman et al., 2016; Satre, 2012; McCaul, 2016; Armstrong et al., 1998; Parry et al., 2014; Papas et al., 2010).

Research to date is mixed regarding the efficacy of alcohol-related interventions among PLWH (Samet and Walley, 2010). Three interventions studied to date have had positive findings (Papas et al., 2011; Hasin et al., 2013; Chander et al., 2015). First, Papas, et al tested the preliminary efficacy of a culturally adapted 6-session cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention delivered by paraprofessionals relative to a usual care, assessment-only control condition among PLWH receiving care (n=102) at a Kenyan outpatient HIV clinic (Papas et al., 2011). The intervention was associated with a reduction in percent drinking days and number of drinking days after 30 days and greater abstinence after 90 days (Papas et al., 2011). In the U.S., Hasin et al recruited 258 heavy drinkers with HIV from a large urban HIV primary care clinic. They compared an active control condition (educational materials and advice to reduce drinking at baseline and 30- and 60-day follow-ups) to two intervention arms based on motivational interviewing (MI) (Hasin et al., 2013). The MI arm included a single 20–25 minute session of counselor-delivered MI with two 15-minute boosters at 30- and 60-days; the other arm (“MI+”) additionally included daily calls with “HealthCall”—an interactive voice-response (IVR) offering personalized feedback (Hasin et al., 2013). Overall group differences in the number of drinking days were observed at 60 days, with both MI and MI+ associated with fewer drinking days relative to the control group. No differences were observed between MI and MI+ in the full sample, although MI+ was associated with fewer drinking days relative to MI among participants meeting criteria for alcohol dependence at baseline (but not among those who did not) (Hasin et al., 2013). Most recently, Chander et al tested a 2-session (plus 2 booster calls) brief intervention relative to a control among 74 HIV+ women from an urban HIV clinic and found that the intervention was associated with reduced frequency of alcohol use at 90 days (Chander et al., 2015). While long-term outcomes, and outcomes beyond self-reported consumption (which is highly susceptible to social desirability bias) have not been measured, findings from these intervention studies suggest that alcohol use may be modifiable among PLWH who drink heavily. Moreover, the IVR component of Hasin’s MI+ has now been enhanced to be delivered via smartphones, with strong findings regarding acceptability and feasibility (Hasin et al., 2014). To the extent it is feasible, future research should measure long-term and objective clinical outcomes of these types of interventions, as well as to investigate sub-group differences in responses, and their potential for translation into real-world settings. Although likely to be dependent on specific contexts and settings, implementing multi-session interventions across settings may be met with substantial barriers (Papas et al., 2011; Papas et al., 2010). However, repeated brief interventions or mobile applications coupled with a single-session of MI may hold promise for translation into HIV clinics and resource poor settings.

Summary and Future Directions

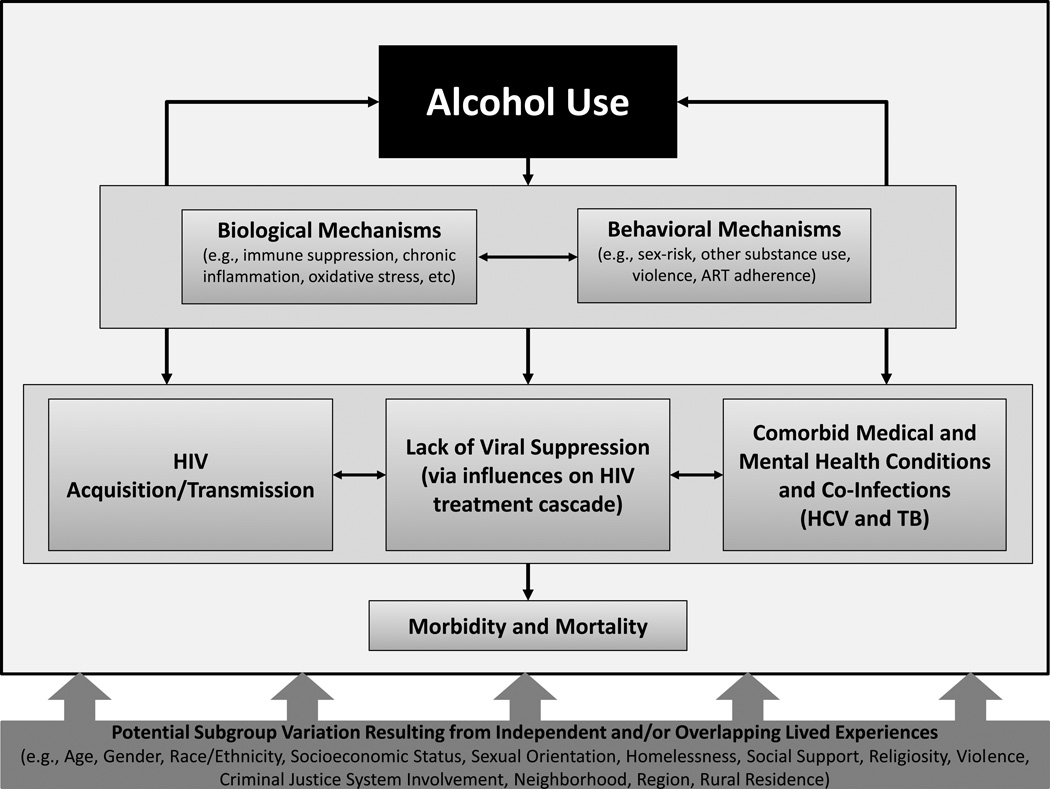

Alcohol use is common among PLWH, and is associated with HIV acquisition and transmission, lack of viral suppression, common comorbid conditions, and ultimately morbidity and mortality via both biological (e.g., oxidative stress) and behavioral (e.g., ART adherence) mechanisms (see: Figure 1). Associations between alcohol use and HIV-related care and outcomes are likely to be influenced by independent and/or overlapping lived experiences of vulnerable sub-populations that are disproportionately represented among PLWH (e.g., sexual minorities, homeless populations). Interventions to modify drinking and improve HIV-related risks and outcomes have been tested in various populations with limited success to date.

Figure 1.

The Influence of Alcohol Use on HIV Care and Outcomes

Our review suggests further research in several areas. Consistent with NIH priorities (National Institutes of Health, 2015), substantial research is needed to better understand alcohol’s influence on co-infections and comorbid conditions that are common among PLWH, including elucidating the mechanisms by which alcohol use is impacting comorbidities. While research suggests the possibility that no level of alcohol use may be considered “safe” for PLWH (Justice et al.), given the high prevalence of alcohol use among PLWH, it will be necessary to better understand which patterns of use substantially increase risks and how. These investigations will require measures of all levels of drinking (including non-drinking). This work should also quantify how changes in alcohol use can alter the course of HIV-related outcomes. Studies that assess whether state-of-the-art medications are safe for co-infected PLWH who drink alcohol are needed in order to ensure adequate treatment of common co-infections. While new medications have emerged that appear to be highly effective at controlling both HCV and TB, contraindications of previous medications, as well as resulting stigma are likely to be barriers to treatment for PLWH who drink and have common co-infections.

Future studies of alcohol’s influence on common comorbidities among PLWH will need to explicitly address measurement issues plaguing the extant literature. While many studies of adverse outcomes among PLWH have not addressed alcohol use at all, many that have, have used alcohol measurements of varying quality. Future studies among PLWH, especially those of interventions which can be prone to mis-report, should include validated self-report measures of alcohol use. While diary-based methods of assessing consumption, such as Timeline Follow Back methods (Sobell et al., 1996), are considered state-of-the-art self-report measures, validated alcohol screens such as the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (Babor et al., 1989) and its abbreviated versions (i.e., the “AUDIT-C” made up of the first three questions regarding consumption (Bush et al., 1998; Bradley et al., 2007; Dawson et al., 2005), and the “AUDIT-3” comprised of the third question assessing heavy episodic drinking (Smith et al., 2009)) are also commonly-used self-report-based methods. When possible, due to limitations of self-report measures (e.g., social desirability bias, recall bias), biological measurements such as phosphatidylethanol (PEth) are recommended (though these also have limitations such as lack of sensitivity for low but still risky amounts) (Hahn et al., 2012; Wurst et al., 2005; Bajunirwe et al., 2014; Asiimwe et al., 2015), as well as objective measures of alcohol-related health consequences. Selection of optimal measures will depend on populations and contexts studied, and the purpose of the measurement. At all phases of this research, subgroup variation in associations should be identified, such that risks specific to vulnerable populations that are over-represented among PLWH (e.g., racial/ethnic minorities, MSM, people with co-occurring substance use, mental health conditions, and homelessness, and the intersections of these identities) are understood.

This research should serve as foundational work that can be translated into a next generation of intervention studies. Future interventions should address alcohol use at individual and policy levels and at all phases from transmission to treatment of HIV. Because alcohol use is prevalent and persistent among PLWH even after exposure to interventions, future interventions should focus on improving engagement in and adherence to HIV care, reducing acute health care utilization, and mitigating comorbid complications in the context of continued drinking. For instance, given the effectiveness of ART for treating HIV, and that alcohol use is a potential modifiable risk factor for non-adherence, this can be considered a challenging but reasonable area for continued research. Given that reductions in alcohol use observed in earlier studies have not translated into improvements in ART, interventions aimed at clustered risks and focused on clearly identified mechanisms linking alcohol use and ART are likely needed. Future interventions should be designed to provide information regarding the potential magnitude of benefit in HIV-related care and outcomes that may be obtained by addressing alcohol use. Once effective interventions are identified, identifying ways to implement them in real world health care settings will be important, as well as understanding barriers to doing so.

By making further progress on understanding the ramifications of alcohol use among PLWH in the era of HIV as a chronic condition, research should inform how we can mitigate transmission, achieve viral suppression and avoid exacerbating common comorbidities of HIV and alcohol use while making progress toward the 90-90-90 goals set out by the WHO (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2014).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors do not have conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES CITED

- Alter MJ. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and HIV co-infection. Journal of Hepatology. 2006;44:S6–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amedee AM, Nichols WA, Robichaux S, et al. Chronic alcohol abuse and HIV disease progression: studies with the non-human primate model. Curr HIV Res. 2014;12:243–253. doi: 10.2174/1570162x12666140721115717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amruth G, Praveen-Kumar S, Nataraju B, et al. HIV Associated Sensory Neuropathy. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:MC04–MC07. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8143.4531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand P, Springer SA, Copenhaver MM, et al. Neurocognitive impairment and HIV risk factors: a reciprocal relationship. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:1213–1226. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9684-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, et al. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69:1789–1799. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armah KA, McGinnis K, Baker J, et al. HIV status, burden of comorbid disease, and biomarkers of inflammation, altered coagulation, and monocyte activation. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2012;55:126–136. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong MA, Midanik LT, Klatsky AL. Alcohol consumption and utilization of health services in a health maintenance organization. Medical Care. 1998;36:1599–1605. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199811000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asiimwe SB, Fatch R, Emenyonu NI, et al. Comparison of Traditional and Novel Self-Report Measures to an Alcohol Biomarker for Quantifying Alcohol Consumption Among HIV-Infected Adults in Sub-Saharan Africa. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2015;39:1518–1527. doi: 10.1111/acer.12781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athyros VG, Liberopoulos EN, Mikhailidis DP, et al. Association of drinking pattern and alcohol beverage type with the prevalence of metabolic syndrome, diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, and peripheral arterial disease in a Mediterranean cohort. Angiology. 2007;58:689–697. doi: 10.1177/0003319707306146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attonito J. The influence of neurocognitive impairment, alcohol and other drug (AOD) use, and psychosocial factors on antiretroviral treatment adherence, service utilization and viral load among HIV-seropositive adults; Dissertation. Florida International University, FIU Digital Commons. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Attonito JM, Devieux JG, Lerner BD, et al. Exploring Substance Use and HIV Treatment Factors Associated with Neurocognitive Impairment among People Living with HIV/AIDS. Front Public Health. 2014;2:105. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azar MM, Springer SA, Meyer JP, et al. A systematic review of the impact of alcohol use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and health care utilization. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010a;112:178–193. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azar MM, Springer SA, Meyer JP, et al. A systematic review of the impact of alcohol use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and health care utilization. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010b;112:178–193. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Saunders J, et al. AUDIT: Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: guidelines for use in primary health care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bagby GJ, Zhang P, Purcell JE, et al. Chronic binge ethanol consumption accelerates progression of simian immunodeficiency virus disease. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:1781–1790. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajunirwe F, Haberer JE, Boum Y, 2nd, et al. Comparison of self-reported alcohol consumption to phosphatidylethanol measurement among HIV-infected patients initiating antiretroviral treatment in southwestern Uganda. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balagopal A, Philp FH, Astemborski J, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-related microbial translocation and progression of hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:226–233. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum MK, Rafie C, Lai S, et al. Alcohol use accelerates HIV disease progression. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2010;26:511–518. doi: 10.1089/aid.2009.0211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedimo RJ, McGinnis KA, Dunlap M, et al. Incidence of non-AIDS-defining malignancies in HIV-infected versus noninfected patients in the HAART era: impact of immunosuppression. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;52:203–208. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b033ab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson AM, L’Engle K, Mwarogo P, et al. Levels of alcohol use and history of HIV testing among female sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS Care. 2014;26:1619–1624. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.938013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KM, Cooperman NA, Newville H, et al. Self-efficacy and depression as mediators of the relationship between pain and antiretroviral adherence. AIDS Care. 2009;21:244–248. doi: 10.1080/09540120802001697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KM, Kunins HV, Jackson JL, et al. Association Between Alcohol Consumption and Both Osteoporotic Fracture and Bone Density. The American journal of medicine. 2008;121:406–418. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilal U, Lau B, Lazo M, et al. Interaction Between Alcohol Consumption Patterns, Antiretroviral Therapy Type, and Liver Fibrosis in Persons Living with HIV. Aids Patient Care and STDS. 2016;30:200–207. doi: 10.1089/apc.2016.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:721–728. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bor J, Geldsetzer P, Venkataramani A, et al. Quasi-experiments to establish causal effects of HIV care and treatment and to improve the cascade of care. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2015;10:495–501. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges AH, Dubrow R, Silverberg MJ. Factors contributing to risk for cancer among HIV-infected individuals, and evidence that earlier combination antiretroviral therapy will alter this risk. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2014;9:34–40. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, et al. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:1208–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite RS, Fang Y, Tate J, et al. Do Alcohol Misuse, Smoking, and Depression Vary Concordantly or Sequentially? A Longitudinal Study of HIV-Infected and Matched Uninfected Veterans in Care. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:566–572. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1117-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite RS, McGinnis KA, Conigliaro J, et al. A temporal and dose-response association between alcohol consumption and medication adherence among veterans in care. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:1190–1197. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171937.87731.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, et al. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nature Medicine. 2006;12:1365–1371. doi: 10.1038/nm1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant KJ, Nelson S, Braithwaite RS, et al. Intergrating HIV/AIDS and alcohol research. Alcohol Res Health. 2010;33:167–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;158:1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt AA, McGinnis K, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, et al. HIV infection and the risk of diabetes mellitus. AIDS. 2009;23:1227–1234. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832bd7af. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo M, Martinez E. Update on metabolic issues in HIV patients. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2014;9:332–339. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco MA, Esser MB, Sparks A, et al. HIV-Alcohol Risk Reduction Interventions in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review of the Literature and Recommendations for a Way Forward. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:484–503. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1233-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrico AW, Hunt PW, Emenyonu NI, et al. Unhealthy Alcohol Use is Associated with Monocyte Activation Prior to Starting Antiretroviral Therapy. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2015;39:2422–2426. doi: 10.1111/acer.12908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrieri MP, Protopopescu C, Le Moing V, et al. Impact of immunodepression and moderate alcohol consumption on coronary and other arterial disease events in an 11-year cohort of HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy. BMJ Open. 2012:2. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassol E, Malfeld S, Mahasha P, et al. Persistent microbial translocation and immune activation in HIV-1-infected South Africans receiving combination antiretroviral therapy. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2010;202:723–733. doi: 10.1086/655229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawthon PM, Harrison SL, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Alcohol intake and its relationship with bone mineral density, falls, and fracture risk in older men. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54:1649–1657. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report: Diagnoses of HIV Infection and AIDS in the United States and Dependent Areas. 2011:23. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data - United States and 6 U.S. dependent areas - 2010 HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Chander G, Himelhoch S, Moore RD. Substance abuse and psychiatric disorders in HIV-positive patients: epidemiology and impact on antiretroviral therapy. Drugs. 2006a;66:769–789. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chander G, Hutton HE, Lau B, et al. Brief Intervention Decreases Drinking Frequency in HIV-Infected, Heavy Drinking Women: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2015;70:137–145. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chander G, Lau B, Moore RD. Hazardous alcohol use: a risk factor for non-adherence and lack of suppression in HIV infection. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006b;43:411–417. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243121.44659.a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chander G, Monroe AK, Crane HM, et al. HIV primary care providers-Screening, knowledge, attitudes and behaviors related to alcohol interventions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandiwana SK, Sebit MB, Latif AS, et al. Alcohol consumption in HIV-I infected persons: a study of immunological markers, Harare, Zimbabwe. Central African Journal of Medicine. 1999;45:303–308. doi: 10.4314/cajm.v45i11.8505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng DM, Libman H, Bridden C, et al. Alcohol consumption and lipodystrophy in HIV-infected adults with alcohol problems. Alcohol. 2009;43:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y, Bond J, et al. Alcohol attributable fraction for injury morbidity from the dose-response relationship of acute alcohol consumption: emergency department data from 18 countries. Addiction. 2015;110:1724–1732. doi: 10.1111/add.13031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cioe PA, Baker J, Kojic EM, et al. Elevated Soluble CD14 and Lower D-Dimer Are Associated With Cigarette Smoking and Heavy Episodic Alcohol Use in Persons Living With HIV. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2015;70:400–405. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin PO, Galea S, Ahern J, et al. Opiates, cocaine and alcohol combinations in accidental drug overdose deaths in New York City, 1990-98. Addiction. 2003;98:739–747. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin PO, Tracy M, Bucciarelli A, et al. Identifying injection drug users at risk of nonfatal overdose. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2007;14:616–623. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SM, Hu X, Sweeney P, et al. HIV viral suppression among persons with varying levels of engagement in HIV medical care, 19 US jurisdictions. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2014;67:519–527. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conen A, Wang Q, Glass TR, et al. Association of alcohol consumption and HIV surrogate markers in participants of the swiss HIV cohort study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2013;64:472–478. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a61ea9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conigliaro J, Gordon AJ, McGinnis KA, et al. How harmful is hazardous alcohol use and abuse in HIV infection: do health care providers know who is at risk? Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2003;33:521–525. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200308010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JA, Burke-Miller JK, Cohen MH, et al. Crack cocaine, disease progression, and mortality in a multicenter cohort of HIV-1 positive women. AIDS. 2008;22:1355–1363. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830507f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CL, Cameron DW. Effect of alcohol use and highly active antiretroviral therapy on plasma levels of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in patients coinfected with HIV and HCV. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2005;(41 Suppl 1):S105–S109. doi: 10.1086/429506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooperman NA. Current research on cigarette smoking among people with HIV. Curr Addict Rep. 2016;3:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Crothers K, Goulet JL, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, et al. Impact of cigarette smoking on mortality in HIV-positive and HIV-negative veterans. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2009;21:40–53. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3_supp.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crothers K, Griffith TA, McGinnis KA, et al. The impact of cigarette smoking on mortality, quality of life, and comorbid illness among HIV-positive veterans. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20:1142–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruess DG, Douglas SD, Petitto JM, et al. Association of resolution of major depression with increased natural killer cell activity among HIV-seropositive women. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:2125–2130. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruess DG, Petitto JM, Leserman J, et al. Depression and HIV infection: impact on immune function and disease progression. CNS Spectr. 2003;8:52–58. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900023452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum-Cianflone N, Roediger MP, Eberly L, et al. Increasing rates of obesity among HIV-infected persons during the HIV epidemic. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum-Cianflone N, Tejidor R, Medina S, et al. Obesity among patients with HIV: the latest epidemic. Aids Patient Care and STDS. 2008;22:925–930. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham WE, Sohler NL, Tobias C, et al. Health services utilization for people with HIV infection: comparison of a population targeted for outreach with the U.S. population in care. Medical Care. 2006;44:1038–1047. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000242942.17968.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrell J, Bedimo R. Non-AIDS-defining cancers among HIV-infected patients. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10:207–216. doi: 10.1007/s11904-013-0166-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza G, Carey TE, William WN, Jr, et al. Epidemiology of head and neck squamous cell cancer among HIV-infected patients. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2014;65:603–610. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, et al. Effectiveness of the derived Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) in screening for alcohol use disorders and risk drinking in the US general population. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:844–854. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164374.32229.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wit S, Sabin CA, Weber R, et al. Incidence and risk factors for new-onset diabetes in HIV-infected patients: the Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1224–1229. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeken JF, Tjen ALA, Rudek MA, et al. The rising challenge of non-AIDS-defining cancers in HIV-infected patients. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2012;55:1228–1235. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks SG. Immune dysfunction, inflammation, and accelerated aging in patients on antiretroviral therapy. Topics in HIV medicine : a publication of the International AIDS Society, USA. 2009;17:118–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks SG. HIV infection, inflammation, immunosenescence, and aging. Annual Review of Medicine. 2011;62:141–155. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-042909-093756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deiss RG, Mesner O, Agan BK, et al. Characterizing the Association Between Alcohol and HIV Virologic Failure in a Military Cohort on Antiretroviral Therapy. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016;40:529–535. doi: 10.1111/acer.12975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delker E, Brown Q, Hasin DS. Alcohol Consumption in Demographic Subpopulations: An Epidemiologic Overview. Alcohol Research. 2016;38:7–15. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v38.1.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon SM, Lee EJ, Kotter CV, et al. An altered intestinal mucosal microbiome in HIV-1 infection is associated with mucosal and systemic immune activation and endotoxemia. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:983–994. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douek D. HIV disease progression: immune activation, microbes, and a leaky gut. Topics in HIV medicine : a publication of the International AIDS Society, USA. 2007;15:114–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Kenny DA, et al. A reanalysis of a behavioral intervention to prevent incident HIV infections: including indirect effects in modeling outcomes of Project EXPLORE. AIDS Care. 2013;25:805–811. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.748870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman EJ, Dinh A, Radulescu R, et al. Combining rapid HIV testing and a brief alcohol intervention in young unhealthy drinkers in the emergency department: a pilot study. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38:539–543. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.701359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman EJ, Hansen NB, Cutter CJ, et al. Implementation of integrated stepped care for unhealthy alcohol use in HIV clinics. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2016;11:1. doi: 10.1186/s13722-015-0048-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbirt D, Mahlab-Guri K, Bezalel-Rosenberg S, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) Isr Med Assoc J. 2015;17:54–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlandson KM, Allshouse AA, Jankowski CM, et al. Risk factors for falls in HIV-infected persons. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2012;61:484–489. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182716e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskild A, Petersen G. Cigarette smoking and drinking of alcohol are not associated with rapid progression to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome among homosexual men in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine. 1994;22:209–212. doi: 10.1177/140349489402200309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DL, Ten Have TR, Douglas SD, et al. Association of depression with viral load, CD8 T lymphocytes, and natural killer cells in women with HIV infection. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1752–1759. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatch R, Bellows B, Bagenda F, et al. Alcohol consumption as a barrier to prior HIV testing in a population-based study in rural Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:1713–1723. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0282-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Tests of causal links between alcohol abuse or dependence and major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:260–266. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredericksen RJ, Edwards TC, Merlin JS, et al. Patient and provider priorities for self-reported domains of HIV clinical care. AIDS Care. 2015;27:1255–1264. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1050983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman ND, Schatzkin A, Leitzmann MF, et al. Alcohol and head and neck cancer risk in a prospective study. British Journal of Cancer. 2007;96:1469–1474. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiberg M, Bebu I, Tracy R, et al. D-dimer doesn’t return to pre-HIV levels after therapy and is linked with HANA events; Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Seattle, WA. 2015. pp. 240–241. [Google Scholar]

- Freiberg MS, Cabral HJ, Heeren TC, et al. Alcohol consumption and the prevalence of the Metabolic Syndrome in the US.: a cross-sectional analysis of data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2954–2959. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.2954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiberg MS, Chang CC, Kuller LH, et al. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA internal medicine. 2013;173:614–622. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiberg MS, McGinnis KA, Kraemer K, et al. The association between alcohol consumption and prevalent cardiovascular diseases among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;53:247–253. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c6c4b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster D, Cheng DM, Quinn EK, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection is associated with all-cause and liver-related mortality in a cohort of HIV-infected patients with alcohol problems. Addiction. 2014;109:62–70. doi: 10.1111/add.12367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster D, Tsui JI, Cheng DM, et al. Impact of lifetime alcohol use on liver fibrosis in a population of HIV-infected patients with and without hepatitis C coinfection. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013 doi: 10.1111/acer.12129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan FH, Bing EG, Fleishman JA, et al. The prevalence of alcohol consumption and heavy drinking among people with HIV in the United States: results from the HIV cost and services utilization study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:179–186. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghebremichael M, Paintsil E, Ickovics JR, et al. Longitudinal association of alcohol use with HIV disease progression and psychological health of women with HIV. AIDS Care. 2009;21:834–841. doi: 10.1080/09540120802537864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano TP, Visnegarwala F, White AC, Jr, et al. Patients referred to an urban HIV clinic frequently fail to establish care: factors predicting failure. AIDS Care. 2005;17:773–783. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331336652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodness TM, Palfai TP, Cheng DM, et al. Depressive symptoms and antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation among HIV-infected Russian drinkers. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:1085–1093. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0674-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757–766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JE, Saveanu RV, Bornstein RA. The effect of previous alcohol abuse on cognitive function in HIV infection. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:249–254. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green TC, Kershaw T, Lin H, et al. Patterns of drug use and abuse among aging adults with and without HIV: a latent class analysis of a US Veteran cohort. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;110:208–220. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guaraldi G, Orlando G, Zona S, et al. Premature Age-Related Comorbidities Among HIV-Infected Persons Compared With the General Population. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2011;53:1120–1126. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn JA, Dobkin LM, Mayanja B, et al. Phosphatidylethanol (PEth) as a biomarker of alcohol consumption in HIV-positive patients in sub-Saharan Africa. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36:854–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn JA, Samet JH. Alcohol and HIV disease progression: weighing the evidence. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7:226–233. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0060-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall HI, Geduld J, Boulos D, et al. Epidemiology of HIV in the United States and Canada: current status and ongoing challenges. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;(51 Suppl 1):S13–S20. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a2639e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen AB, Gerstoft J, Kronborg G, et al. Incidence of low and high-energy fractures in persons with and without HIV infection: a Danish population-based cohort study. AIDS. 2012;26:285–293. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834ed8a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harezlak J, Buchthal S, Taylor M, et al. Persistence of HIV-associated cognitive impairment, inflammation, and neuronal injury in era of highly active antiretroviral treatment. AIDS. 2011;25:625–633. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283427da7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Aharonovich E, Greenstein E. HealthCall for the smartphone: technology enhancement of brief intervention in HIV alcohol dependent patients. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2014;9:5. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-9-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Aharonovich E, O’Leary A, et al. Reducing heavy drinking in HIV primary care: a randomized trial of brief intervention, with and without technological enhancement. Addiction. 2013;108:1230–1240. doi: 10.1111/add.12127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasse B, Ledergerber B, Furrer H, et al. Morbidity and Aging in HIV-Infected Persons: The Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2011;53:1130–1139. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser KF, Knapp PE. Interactions of HIV and drugs of abuse: the importance of glia, neural progenitors, and host genetic factors. International Review of Neurobiology. 2014;118:231–313. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801284-0.00009-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Jr, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology. 2010;75:2087–2096. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors. Journal of Neurovirology. 2011;17:3–16. doi: 10.1007/s13365-010-0006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot CS, Stoner SA, Pantalone DW, et al. Alcohol use and antiretroviral adherence: review and meta-analysis. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;52:180–202. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b18b6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High KP, Brennan-Ing M, Clifford DB, et al. HIV and aging: state of knowledge and areas of critical need for research. A report to the NIH Office of AIDS Research by the HIV and Aging Working Group. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2012;(60 Suppl 1):S1–S18. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825a3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hile SJ, Feldman MB, Alexy ER, et al. Recent Tobacco Smoking is Associated with Poor HIV Medical Outcomes Among HIV-Infected Individuals in New York. AIDS Behav. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1273-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard AA, Arnsten JH, Gourevitch MN. Effect of alcohol consumption on diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;140:211–219. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-6-200403160-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Han H, Lau MY, et al. Effects of combined alcohol and anti-HIV drugs on cellular stress responses in primary hepatocytes and hepatic stellate and kupffer cells. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2015;39:11–20. doi: 10.1111/acer.12608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt PW, Sinclair E, Rodriguez B, et al. Gut epithelial barrier dysfunction and innate immune activation predict mortality in treated HIV infection. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2014;210:1228–1238. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson DL, Tang AM, Spiegelman D, et al. Incidence of metabolic syndrome in a cohort of HIV-infected adults and prevalence relative to the US population (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2006;43:458–466. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243093.34652.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. [accessed February 15, 2016];90-90-90—an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. 2014 http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2014/90-90-90.

- Justice A, Falutz J. Aging and HIV: an evolving understanding. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2014;9:291–293. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justice AC, McGinnis KA, Tate JP, et al. Risk of mortality and physiologic injury evident with lower alcohol exposure among HIV infected compared with uninfected men. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016;161:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabali C, Cheng DM, Brooks DR, et al. Recent cigarette smoking and HIV disease progression: no evidence of an association. AIDS Care. 2011;23:947–956. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.542128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Cherry C, Kalichman MO, et al. Randomized clinical trial of HIV treatment adherence counseling interventions for people living with HIV and limited health literacy. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2013a;63:42–50. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318286ce49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Grebler T, Amaral CM, et al. Intentional non-adherence to medications among HIV positive alcohol drinkers: prospective study of interactive toxicity beliefs. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013b;28:399–405. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2231-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Vermaak R, et al. Randomized trial of a community-based alcohol-related HIV risk-reduction intervention for men and women in Cape Town South Africa. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;36:270–279. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanis JA, Johansson H, Johnell O, et al. Alcohol intake as a risk factor for fracture. Osteoporosis International. 2004;16:737–742. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1734-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]