Abstract

Introduction

Failure to rescue (FTR: the conditional probability of death after complication) has been studied in trauma cohorts, but the impact of age and pre-existing conditions (PECs) on risk of FTR is not well-known. We assessed the relationship between age and PECs on the risk of experiencing serious adverse events (SAE) subsequent FTR in trauma patients with the hypothesis that increased comorbidity burden and age would be associated with increased FTR.

Materials and Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort analysis at an urban level 1 trauma center in PA. All patients age ≥ 16 years with minimum abbreviated injury scale score ≥ 2 from 2009–2013 were included. Univariate logistic regression models for SAE and FTR were developed using age, PECs, demographics, and injury physiology. Variables found to be associated with the endpoint of interest (p≤0.2) in univariate analysis were included in separate multivariable logistic regression models for each outcome.

Results

SAE occurred in 1,136/7533 (15.1 %) of patients meeting inclusion criteria (median age 42 (IQR 26–59), 53% African American, 72% male, 79% blunt, median ISS 10 (IQR 5–17)). Of those who experienced a SAE, 129/1136 patients subsequently died (FTR = 11.4%). Development of SAE and FTR was associated with age ≥ 70 (OR 1.58–1.78, 95% CI 1.13–2.82). Renal disease was the only pre-existing condition associated with both SAE and FTR.

Conclusions

Trauma patients with renal disease are most at increased risk for both SAE and FTR, but other PECs associated with SAE are not necessarily those associated with FTR. Future interventions designed to reduce FTR events should target this high-risk cohort.

Keywords: Aged, Comorbidity, Wounds and Injuries, Postoperative Complications, Fatal Outcome, Cohort Studies

Introduction

While mortality and complication rates have been used as proxies of quality of care after injury for decades, the Failure to Rescue (FTR) rate has only relatively recently been examined as an outcome metric in trauma cohorts (1, 2). Developed by Silber et al. in 1992, FTR is defined as death after a major complication (hereafter referred to as a serious adverse events, or SAE) (3), and speaks to how well centers recognize and SAE. The FTR rate has several potential advantages over more convention outcome metrics. While it has been repeatedly shown that center level SAE rates correlate poorly with center level mortality rates (4, 5), center level FTR rates are strongly associated with center level mortality across a wide variety of elective surgical populations (6–8). Moreover, relative to risk of SAE, risk of FTR is more strongly associated with potentially modifiable center level factors such as staffing patterns and infrastructure (9). As these structural variables are potentially subject to modification, focusing on FTR represents an opportunity to reduce mortality that focusing on SAE alone may not.

While a promising avenue of inquiry to reduce mortality rates, much of what has been published regarding FTR in the trauma population has either focused on demonstrating that the relationships between center-level SAE, FTR, and mortality rates are similar to what have been demonstrated in elective surgical cohorts (1, 2) or on identifying center-level variables (e.g. volume (10), proportion of minority patients (11)) that are associated with differential rates of FTR. Translating observational knowledge of FTR into improvements in center-level FTR rates is contingent upon developing hypotheses surrounding specific interventions and then testing them in a trauma populations at high risk for FTR. The literature regarding the characteristics of this at-risk population after injury is currently sparse, but PECs and age are known to be important drivers in other populations (12, 13). Unfortunately, the largest study to date examining the association between PECs and FTR in a trauma population is limited in that in includes patients only up to age 65 (14). One of the main proposed drivers of increased rates of SAE and mortality in the United States is the increased rate of pre-existing conditions (PECs) in the elderly (15). Up to 86% of older Americans are thought to have at least one PEC (16) and both age (17, 18) and PECs (18–21) contribute to risk of major SAE after injury. Older trauma patients have increased rates of SAE and mortality rates as compared to their younger counterparts (22–25) and by 2020, over ⅕ of the US population will be over the age of 65 (26). Given the increased risk of SAE in the elderly population and the increased proportion of injured patients they will come to represent as the population ages, understanding risk factors for FTR in this population represents a critical gap in our current knowledge.

To that end, the purpose of this study was to identify specific PECs as risk factors for a.) SAE and b.) Death after SAE (also known as FTR) in a large cohort of trauma patients. We hypothesized that the same PECs that conferred risk of SAE would also independently contribute to risk of FTR after these complications. Because PECs are often known at admission, the ultimate goal of this work is to help identify a high-risk subset of trauma patients who might benefit from targeted interventions to reduce death, or FTR, after experiencing SAE.

Materials and Methods

Patients

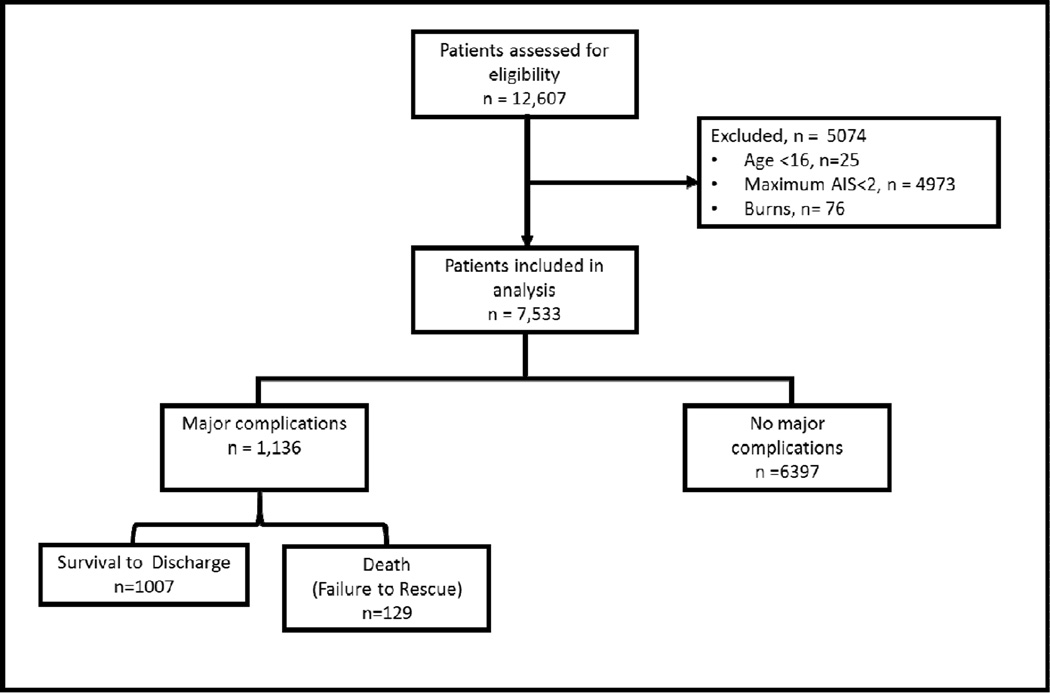

We performed a retrospective cohort study at a single urban level 1 trauma center in PA. Patients eligible for inclusion (n=7,533) had the following characteristics: seen at the trauma center between 1/1/2009–12/31/2013, ≥ 16 years old, and an Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) ≥ 2 for at least one body region. We excluded patients with a primary diagnosis of burn. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria of the study. Abbreviations: AIS = Abbreviated Injury Scale.

Data

The data for this study was obtained from our institutional registry which is part of the Pennsylvania Trauma Outcomes Study (PTOS), a large trauma registry in the state of Pennsylvania. This database is maintained by the Pennsylvania Trauma Systems Foundation (PTSF), which is responsible for accreditation and quality of trauma centers in Pennsylvania. A total of ~40,000 unique records are submitted to PTOS annually from trauma centers in the state, which are subject to mandatory reporting of data on trauma patients. To ensure the quality of data collection at the center-level, specially trained registrars at each trauma center prospectively abstract detailed data from the medical chart of each patient meeting inclusion criteria into the PTOS registry. These data are collected according to standardized definitions put forth by the PTSF and a subset of charts is re-reviewed to ensure inter-rater reliability by registrars. Centrally, the PTSF assures the quality of the data by submitting it to range, logic, and missingness checks. Additionally, subsets of submitted data are re-abstracted by the PTSF during site accreditation visits to verify accuracy. As data quality is linked to accreditation, centers are strongly incentivized to accurately report data and rates of missing data are low (<5% of variables based on previous work (27)).

Variables

Exposures of interest included sex, age, race, injury severity score (ISS), maximum abbreviated injury score (max AIS), Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), admission vital signs, and 26 PECs. We defined PECs according to PTOS definitions (Appendix 12: Pre-existing Conditions, available online at http://www.ptsf.org/upload/2015_PTOS_Manual_FINAL_Updated_4-3-2015.doc) (28). To be included as a PEC in the Pennsylvania Trauma Outcomes Study, conditions must be present before patient arrival at the ED/hospital and ascertainment is based on documentation in the medical record. Data at our center is abstracted prospectively by trained registrars according to standardized definitions for submission to the PTOS, and questions arising as to the presence or nature of PECs are resolved through queries to clinical providers. To avoid multicollinearity concerns in multivariable modelling secondary co-occurrences of related PECs, we condensed related PECs into larger categories. These included Cardiac Disease (history of cardiac surgery, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, or myocardial infarction), Renal disease (baseline creatinine greater than 2.0 mg%, dialysis dependence), Liver disease (documented history of cirrhosis, gastric or esophageal varices, baseline bilirubin>2.0), and Malignancy (existence of metastasis, undergoing current cancer therapy, active chemotherapy).

The primary outcomes of interest were a) development of SAE and b) death after SAE (FTR). Serious adverse events were as defined by the PTOS data dictionary (Appendix 9: Occurrences, available online at http://www.ptsf.org/upload/2015_PTOS_Manual_FINAL_Updated_4-3-2015.doc). The occurrence of an SAE at our center is as adjudicated by the clinicians caring for the injured patient and these adjudications are monitored by state-mandated performance improvement coordinators who concurrently audit patient care. SAEs used in this work were defined as those used in the original FTR literature (3) and those found to be associated with mortality in univariate logistic regression analysis with p≤ 0.1. FTR was defined as death after a major complication.

Analysis

We first examined the unadjusted association between age and the development of SAE using locally-weighted smoothed scatter plots and determined that an inflection point occurred at approximately age 60, above which the incidence of SAE increased steadily. We therefore considered age as categorical variable binned from 16–59, 60–69, 70–79, 80–89, and ≥90 years. The association between demographic variables, PECs, age, ISS, admission vital signs, and the development of SAE was assessed using univariate logistic regression models. Continuous variables that did not meet parametric assumptions were considered in dichotomous, categorical, or fractional polynomial forms, as dictated by the association between the outcome variable and the distribution of the predictor variables. Pre-existing conditions that occurred in less than 0.5% of the cohort (~50 patients) were not evaluated. Those variables found to be associated with major complications with a p value of ≤ 0.2 in univariate models were then entered into a multivariable logistic regression model using a backward stepwise approach. Likelihood ratio test was used to assess for interactions between injury severity, age, and specific PECs. Model calibration was tested using Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) curves, and fit was tested using Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test. In order to create the most parsimonious model, variables which did not improve model discrimination by likelihood ratio test between ROC curves were removed. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata IC14.1 (College Station, TX). This study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Results

Overall, 469/7533 (6.23%) patients in the cohort died. Mortality was higher in those patients who had an SAE than those that did not (11.4% vs 5.2%, p<0.001). The median length of stay in the cohort was 4 days (IQR 2–9 days) and was longer in patients who had SAE than those that did not (4 (IQR 2–7) days vs 17 (IQR 10–26 days), p<0.001). SAE occurred in 1,136/7533 (15.1 %) of patients meeting inclusion criteria. Demographics of patients developing SAE included: median age 42 (IQR 26–59), 53% African American, 72% male, 79% blunt, median ISS 10 (IQR 5–17)). Of those who experienced a SAE, 129/1136 patients died (FTR rate = 11.4%). Results of univariate analysis on the development of major complications and demographic factors, admission vital signs, and PECs can be seen in Table 1. The age distribution of patients who developed SAEs was skewed towards advanced age, and the odds of SAE was significantly higher in each decade over 60 years relative to the age 16–59 group. African American race was associated with lower complication rates, but there was no association between sex and complications. Lower admission GCS and lower systolic blood pressure were strongly associated with development of SAEs, as was penetrating mechanism of trauma and higher injury severity score. Table 2 displays the distribution of individual SAEs in patients who developed SAEs in total and grouped by those who lived or died. The most common SAE overall was pneumonia (17%), and this did not vary significantly in patients who lived vs. died (17% vs. 14% respectively, p=0.34). Serious adverse events that were more common in survivors than those who died included deep venous thrombosis (14% vs 3%, p = 0.001), urinary tract infection (14% vs 2%, p <0.001), and wound infection (7% vs. 2%, p = 0.02) while SAEs more common in those who died than survived included cardiopulmonary arrest (17% vs. 3%, p <0.001), myocardial infarction (3% vs. 1%, p = 0.03), and esophageal intubation (2% vs. 0.1%, p = 0.001).

Table 1.

Demographics, mechanism, injury severity, presenting vital signs, and pre-existing conditions for patients with and without SAEs. Data for nonparametric continuous variables expressed as median (Interquartile Range); parametric continuous variables expressed as mean (Standard Deviation); Categorical values expressed as n (%). P values are for Mann-Whitney test for nonparametric continuous variables and chi square test for categorical variables.

| Patient Characteristic | No Serious Adverse Event n=6397 |

Serious Adverse Event n =1136 |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 41 (IQR 25–57) | 47 (IQR 28–68) | 0.001 |

| Male gender | 4,606 (72%) | 839 (74%) | 0.2 |

| Race | <0.001 | ||

| African American | 3,339 (52%) | 506 (45%) | |

| Caucasian | 2,624 (41%) | 566 (50%) | |

| Asian | 131 (2%) | 26 (2%) | |

| Other | 303 (5%) | 38 (3%) | |

| Blunt Mechanism | 5109 (80%) | 864 (76%) | 0.004 |

| Admission SBP, mmHg | 138 (IQR 123–153) | 135 (IQR 117–152) | <0.001 |

| Glasgow Coma Score | 15 (IQR 15–15) | 14 (IQR 6–15) | 0.001 |

| Injury Severity Score | 9 (IQR 5–14) | 21 (11–30) | <0.001 |

| Maximum AIS | 3 (IQR 2–3) | 4 (IQR 3–5) | 0.001 |

| Pre-Existing Conditions | |||

| Hypertension | 1632 (25.5%) | 395 (34.8%) | <0.001 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 1027 (16.0%) | 220 (19.4%) | 0.006 |

| Illicit drug use | 1091 (17.0%) | 216 (19.0%) | 0.1 |

| Ethanol Abuse | 891 (13.9%) | 196 (17.2%) | 0.004 |

| Cardiac Disease | 468 (7.3%) | 163 (14.3%) | <0.001 |

| DM | 622 (9.7%) | 154 (13.6%) | <0.001 |

| Tobacco Use | 907 (14.2%) | 142 (12.5%) | 0.1 |

| Asthma | 633 (9.9%) | 104 (9.1%) | 0.5 |

| Malignancy | 284 (4.4%) | 79 (6.9%) | <0.001 |

| Coagulopathy | 195 (3.0%) | 66 (5.8%) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 215 (3.4%) | 65 (5.7%) | <0.001 |

| CVA | 203 (3.2%) | 65 (5.7%) | <0.001 |

| Thyroid Disease | 276 (4.3%) | 56 (4.9%) | 0.3 |

| Obesity | 172 (2.7%) | 54 (4.8%) | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 155 (2.4%) | 49 (4.3%) | <0.001 |

| Dependent Functional Status | 153 (2.4%) | 39 (3.4%) | 0.05 |

| Anemia | 93 (1.4%) | 31 (2.7%) | 0.003 |

| Seizure History | 134 (2.1%) | 31 (2.7%) | 0.2 |

| Renal Disease | 72 (1.1%) | 31 (2.7%) | <0.001 |

| Arthritis | 97 (1.5%) | 27 (2.3%) | 0.04 |

| Liver Disease | 51 (0.8%) | 21 (1.8%) | 0.002 |

| Prior TBI | 125 (2.0%) | 17 (1.5%) | 0.3 |

| Corticosteroid use | 49 (0.8%) | 12 (1.2%) | 0.1 |

| Chronic Respiratory Disease | 39 (0.7%) | 12 (1.0%) | 0.1 |

| ADD | 87 (1.3%) | 12 (1.0%) | 0.5 |

| HIV/AIDS | 76 (1.2%) | 10 (0.9%) | 0.4 |

Abbreviations: SBP= Systolic Blood Pressure; AIS = Abbreviated Injury Scale; DM = Diabetes Mellitus; COPD = Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; CVA = Cerebrovascular Accident; TBI = Traumatic Brain Injury; ADD = Attention Deficit Disorder; HIV/AIDS = Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome.

Table 2.

Frequencies of individual SAEs in patients who developed SAEs grouped by patients who lived or died (FTR). P values are for chi-squared test.

| Serious Adverse Event | All patients with SAEs (n=1136) |

Survived (n=1007) |

Died (FTR) (n=129) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia | 192 (16.9%) | 174 (17%) | 18 (14%) | 0.34 |

| DVT | 142 (12.5%) | 138 (14%) | 4 (3.1%) | 0.001 |

| UTI | 138 (12.15%) | 136 (14%) | 2 (1.6%) | <0.001 |

| Arrhythmia | 88 (7.8%) | 73 (7.3%) | 15 (12%) | 0.08 |

| Acute Respiratory Failure | 81 (7.1%) | 74 (7.4%) | 7 (5.4%) | 0.42 |

| Wound Infection | 73 (6.4%) | 71 (7.1%) | 2 (1.6%) | 0.02 |

| Aspiration Pneumonia | 61 (5.4%) | 51 (5.1%) | 10 (7.8%) | 0.20 |

| Cardiopulmonary Arrest | 48 (4.2%) | 26 (2.6%) | 22 (17%) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary Embolism | 47 (4.1%) | 45 (4.5%) | 2 (1.6%) | 0.12 |

| Coagulopathy | 44 (3.9%) | 22 (2.2%) | 22 (17%) | <0.001 |

| Organ Nerve Vessel Injury | 32 (2.82%) | 27 (2.7%) | 5 (3.9%) | 0.44 |

| Atelectasis | 25 (2.2%) | 25 (2.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0.07 |

| Septicemia | 24 (2.1%) | 23 (2.3%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0.26 |

| Pneumothorax | 19 (1.7%) | 16 (1.6%) | 3 (2.3%) | 0.54 |

| Acute Kidney Injury | 15 (1.3%) | 11 (1.1%) | 4 (3.1%) | 0.06 |

| Decubitus | 15 (1.3%) | 15 (1.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0.16 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 13 (1.1%) | 9 (0.9%) | 4 (3.1%) | 0.03 |

| Pleural Effusion | 12 (1.1%) | 12 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0.21 |

| Gastrointestinal Bleeding | 12 (1.1%) | 10 (1%) | 2 (1.6%) | 0.56 |

| Empyema | 10 (0.9%) | 9 (0.9%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0.89 |

| Sepsis | 9 (0.8%) | 9 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0.28 |

| Postoperative Hemorrhage | 8 (0.7%) | 7 (0.7%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0.92 |

| Progression of Neurologic Injury | 8 (0.7%) | 8 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0.31 |

| ARDS | 7 (0.6%) | 6 (0.6%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0.81 |

| Adverse Drug Reaction | 7 (0.6%) | 7 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0.34 |

| Esophageal Intubation | 5 (0.4%) | 2 (0.2%) | 3 (2.3%) | 0.001 |

| Hypothermia | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0.72 |

Abbreviations: DVT = Deep Venous Thrombosis; UTI = Urinary Tract Infection; ARDS = Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome.

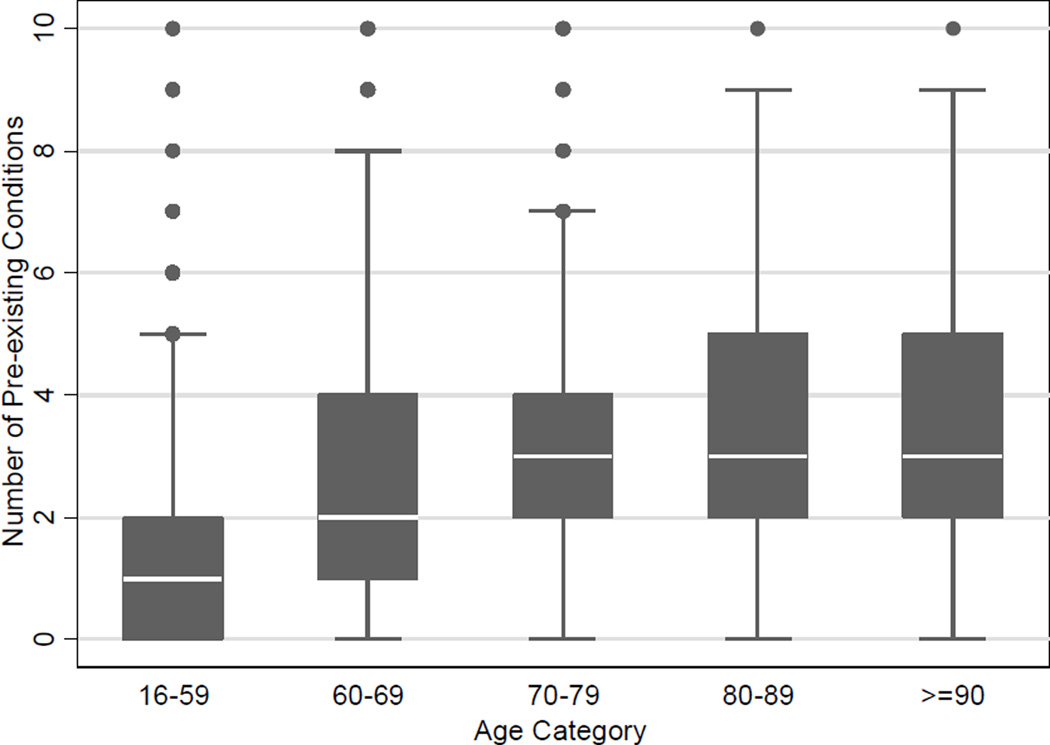

In the overall cohort, 68% of patients had at least one PEC with the most common being hypertension (27%), substance abuse (17%), and psychiatric history (17%). The incidence of PECs increased with age (Figure 2), and nearly all individual PECs were associated with the development of SAE in univariate regression, with only asthma, thyroid disease, prior traumatic brain injury, and HIV/AIDS failing to meet the ≤0.2 p-value threshold for inclusion in multivariable modelling.

Figure 2.

Box plots of the total number of pre-existing conditions by age category. Using Kruskal-Wallis test with p values adjusted for multiple comparisons, The total number of PECs was signifcanlty different between age group 16–59 and all other groups (p<0.001), between age 60–69 and all other groups (<0.001). The total number of PECs was not significantly different for any pairwise comparison between groups 70–79, 80–89, and ≥90 years of age groups.

In multivariable logistic regression modeling, age category, African-American race, penetrating mechanism of injury, admission systolic blood pressure, admission Glasgow Coma Score (GCS), ISS, and maximum Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) were independently associated with the development of SAE. With respect to PECs, hypertension, drug abuse, ethanol abuse, obesity, cardiac disease and renal disease were each independently associated with the development of SAE (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression model on the development of any SAE.

| PATIENT CHARACTERISTIC |

OR for SAE | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGE CATEGORY | ||||

| 16–59 | ref | |||

| 60–69 | 1.26 | 0.97 | 1.64 | 0.081 |

| 70–79 | 1.74 | 1.31 | 2.3 | <0.001 |

| 80–89 | 1.58 | 1.17 | 2.13 | 0.003 |

| >=90 | 1.78 | 1.13 | 2.82 | 0.014 |

| RACE | ||||

| CAUCASIAN | ref | |||

| BLACK | 0.73 | 0.61 | 0.86 | <0.001 |

| ASIAN | 1.15 | 0.69 | 1.89 | 0.594 |

| OTHER | 0.73 | 0.48 | 1.09 | 0.126 |

| INJURY MECHANISM | ||||

| BLUNT | ref | |||

| PENETRATING | 1.29 | 1.05 | 1.59 | 0.015 |

| ADMISSION SBP, MMHG | 1 | 1 | 1.01 | 0.002 |

| GLASGOW COMA SCORE | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.94 | <0.001 |

| INJURY SEVERITY SCORE | 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.06 | <0.001 |

| MAXIMUM AIS | 1.38 | 1.24 | 1.53 | <0.001 |

|

PRE-EXISTING CONDITIONS |

||||

| HYPERTENSION | 1.36 | 1.13 | 1.65 | 0.001 |

| DRUG ABUSE | 1.37 | 1.12 | 1.67 | 0.002 |

| ETHANOL ABUSE | 1.38 | 1.13 | 1.69 | 0.002 |

| OBESITY | 2.05 | 1.43 | 2.94 | <0.001 |

| CARDIAC DISEASE | 1.29 | 1.01 | 1.64 | 0.045 |

| RENAL DISEASE | 2.45 | 1.51 | 3.98 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: SBP= Systolic Blood Pressure; AIS = Abbreviated Injury Scale.

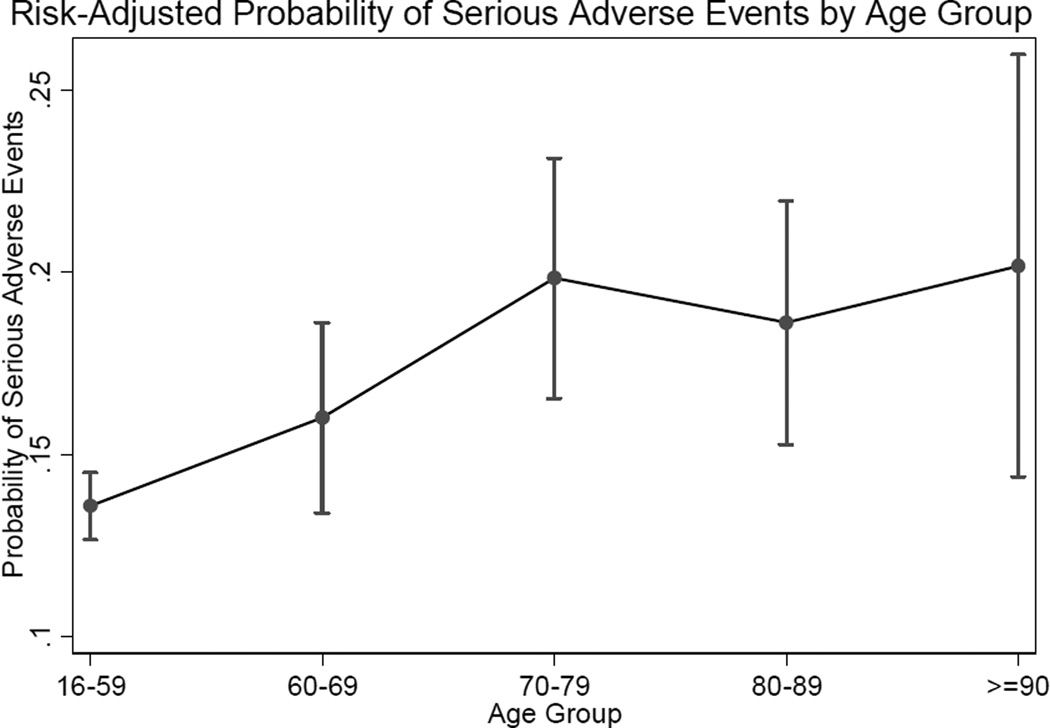

No evidence of effect modification between age and injury severity or age and any PEC was found based on likelihood ratio tests between multivariable models with and without interaction terms for these variables. The discriminative ability of this model was excellent, with a ROC AUC of 0.90 (95% CI 0.89–0.91). The Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic for this model was significant (HL chi-squared 41.6 p<0.001), but visual inspection of observed: expected events revealed excellent calibration. Pairwise comparison of predicted marginal SAE rates revealed that age groups 70–79 (SAE rate 19.8%), 80–89 (SAE rate 18.6%), and ≥90 (SAE rate 20.1%) all had significantly higher adjusted SAE rates than did the 16–59 year-old group (13.6%, p<0.05). Adjusted marginal mean SAE rates by age category can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Risk-adjusted marginal probability of serious adverse events with increasing age based on final multivariable model. Risks adjusted for race, injury mechanism, presenting physiology, overall injury burden (ISS), maximum AIS score, and pre-existing conditions (hypertension, drug abuse, ethanol abuse, obesity, cardiac disease, and chronic kidney disease).

In the subset of patients who experienced SAE, univariate analysis revealed significant differences between those who lived and those who died (Table 4). Patients who died tended to be older, more severely injured overall, and with a single most severe injury as measured by maximum AIS. Patients who died also had lower median admission systolic blood pressure and GCS as compared to those who survived. Pre-existing conditions differed between the groups as well, with the FTR group having higher rates of almost every PEC aside from psychiatric disease, drug abuse, ethanol abuse, tobacco use, and obesity.

Table 4.

Demographics, mechanism, injury severity, presenting vital signs, and pre-existing conditions for patients surviving and dying after SAEs. Data for nonparametric continuous variables expressed as median (Interquartile Range); parametric continuous variables expressed as mean (Standard Deviation); Categorical values expressed as n (%). P values are for Mann-Whitney test for nonparametric continuous variables and chi square test for categorical variables.

| Patient Characteristic | Survived after SAE n=1007 |

Died after SAE (FTR) n =129 |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 47 (IQR 28–66) | 58 (IQR 31–75) | 0.012 |

| Male gender | 743 (74%) | 96 (74%) | 0.9 |

| Race | 0.03 | ||

| African American | 456 (45%) | 50 (39%) | |

| Caucasian | 501 (50%) | 65 (50%) | |

| Asian | 19 (2%) | 7 (5%) | |

| Other | 31 (3%) | 7 (5%) | |

| Blunt Mechanism | 772 (77%) | 92 (72%) | 0.23 |

| Admission SBP, mmHg | 136 (IQR 118–152) | 133 (IQR 102–156) | 0.08 |

| Glasgow Coma Score | 15 (IQR 7–15) | 7 (IQR 3–14) | <0.001 |

| ISS | 20 (IQR 10–29) | 26 (19–38) | <0.001 |

| Maximum AIS | 3 (IQR 3–4) | 4 (IQR 3–5) | <0.001 |

| Pre-Existing Conditions | |||

| Hypertension | 343 (34.1%) | 52 (40.3%) | 0.2 |

| Psychiatric Disease | 202 (20.0%) | 18 (13.9%) | 0.1 |

| Drug Abuse | 208 (20.7%) | 8 (6.2%) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 183 (18.2%) | 13 (10.1%) | 0.02 |

| Cardiac Disease | 136 (13.5%) | 27 (20.9%) | 0.03 |

| Diabetes | 131 (13.0%0 | 23 (17.8%) | 0.1 |

| Tobacco Use | 137 (13.6%) | 5 (3.9%) | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 99 (9.8%) | 5 (3.9%) | 0.02 |

| Malignancy | 66 (6.6%) | 13 (10.1%) | 0.1 |

| Coagulopathy | 53 (5.3%) | 13 (10.1%) | 0.04 |

| Obesity | 50 (5.0%) | 4 (3.1%) | 0.5 |

| Renal Disease | 22 (2.1%) | 9 (7.0%) | 0.005 |

| Liver Disease | 16 (1.6%) | 5 (3.9%) | 0.08 |

| Alzheimer's | 8 (0.8%) | 3 (2.3%) | 0.1 |

| CPR | 1 (0.1%) | 3 (2.3%) | 0.005 |

| Spinal Cord Injury | 2 (0.2%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0.07 |

Abbreviations: SBP= Systolic Blood Pressure; AIS = Abbreviated Injury Scale; DM = Diabetes Mellitus; COPD = Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; CVA = Cerebrovascular Accident; TBI = Traumatic Brain Injury; ADD = Attention Deficit Disorder; HIV/AIDS = Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

In multivariable logistic regression modeling, age remained strongly and significantly associated with FTR. Patients age 60–69 had similar odds of FTR compared to those under 60, but odds of death went up approximately fivefold for patients in the 70–79, 80–89, and the >=90 age group (adjusted OR 4.91, 95%CI 2.49–9.69; OR 5.3, 95%CI 2.52–11.09; OR 9.85, 95%CI 3.36–28.87 respectively). Penetrating mechanism, increased injury severity score, decreased admission systolic blood pressure, and decreased admission GCS likewise were associated with increased odds of FTR. Pre-existing conditions of renal disease, liver disease, and coagulopathy were each independently associated with increased odds of death (Table 5). Substance abuse was associated with a reduced risk of FTR after serious adverse events (OR 0.29, 95%CI 0.13–0.67).

Table 5.

Multivariable logistic regression models on the development of FTR.

| Patient Characteristic | OR for FTR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Category | ||||

| 16–59 | ref | |||

| 60–69 | 1.77 | 0.84 | 3.71 | 0.132 |

| 70–79 | 4.92 | 2.49 | 9.69 | <0.001 |

| 80–89 | 5.3 | 2.53 | 11.09 | <0.001 |

| >=90 | 9.85 | 3.36 | 28.87 | <0.001 |

| Injury Mechanism | ||||

| Blunt | ref | |||

| Penetrating | 2.74 | 1.58 | 4.76 | <0.001 |

| Admission SBP, mmHg | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1 | 0.024 |

| Glasgow Coma Score | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.89 | <0.001 |

| Injury Severity Score | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.04 | 0.002 |

| Pre-existing conditions | <0.001 | |||

| Renal Disease | 5.69 | 2.29 | 14.15 | 0.022 |

| Liver Disease | 3.95 | 1.22 | 12.75 | 0.026 |

| Coagulopathy | 2.38 | 1.11 | 5.1 | 0.004 |

| Drug abuse | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.67 | 0.085 |

Abbreviations: SBP= Systolic Blood Pressure.

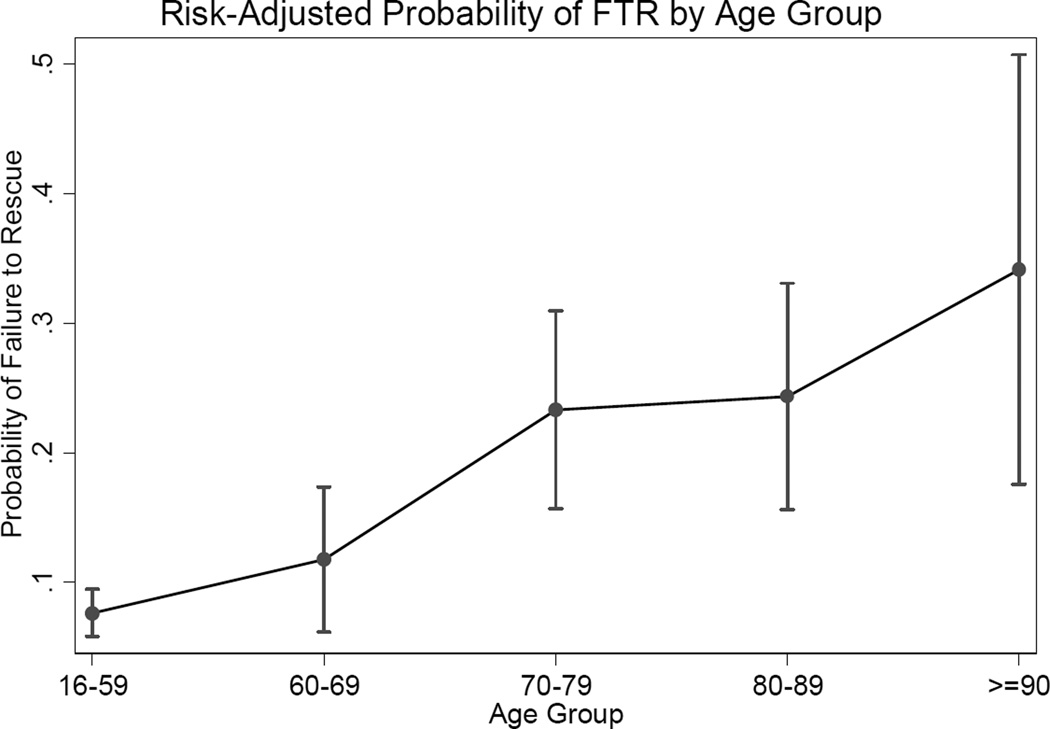

Examination of the possibility of effect modification between ISS and age category no evidence of interaction (Likelihood ratio test = 0.17). The AUC for the ROC curve for the final model was 0.81 (95% CI 0.78–0.85) indicating good discriminative ability. The Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic was 4.9 (p=0.77), indicating good calibration of the model. The marginal mean FTR rates by age category can be seen in Figure 4; rates of FTR appear to increase as age category increases, but the confidence intervals are wide. In pairwise comparison of adjusted marginal FTR rates, the FTR rates for 70–79 group (FTR 23.3%), the 80–89 group (FTR 24.3%) and the ≥90 group (FTR rate 34.1%) were not statistically significantly different but all were significantly higher than those of the 16–59 (FTR rate 7.6%) and 60–69 group (FTR rate 11.8) with significance level of less than 0.05.

Figure 4.

Risk-adjusted marginal probability of failure to rescue with increasing age based on final multivariable model. Risks adjusted for injury mechanism, Injury Severity Score, admission physiology, and pre-existing conditions (renal disease, liver disease, coagulopathy, and drug abuse)

Discussion

Although initially described nearly 25 years ago, FTR analyses have enjoyed a recent resurgence in interest by surgical outcomes researchers (29–31). The attractive properties of the FTR metric can be summarized as follows: first, while rates of SAE have repeatedly been shown to correlate poorly with mortality rates at the center level (4, 5), FTR rates are clearly associated with mortality rates in a multiple elective surgical cohorts (31–33). Second, while rates of SAE and FTR are strongly associated with patient factors such as pre-existing conditions and age (9), FTR rates are relatively more strongly associated with center level variables such as nurse to bed ratios, nursing education levels (34), and board certification status of physicians (35). While patient factors are generally not subject to modification, center level factors generally are, thus suggesting a possible mechanism for reducing center level mortality by reducing FTR.

Despite its great promise, little work has been performed which seeks to translate center-level variability in FTR into tangible reductions in individual center rates. To design interventions targeted at reducing FTR, we believe it is critical to first identify the populations at highest risk. By identifying PECs and age cutoffs associated with increased risk of SAE and FTR, we have identified a subset of trauma patients at greatest risk for poor outcomes. We found that the factors that contributed to both SAE and FTR were age ≥ 70, renal disease, penetrating mechanism of injury, decreased GCS, and increased ISS. Several additional PECs (hypertension, obesity, cardiac disease and ethanol abuse) and increased maximum abbreviated injury scale also increased the risk for SAE in trauma patients, but were not independently related to FTR. By contrast, two different PECs (liver disease and coagulopathy) were associated with increased odds of death after complication (FTR), but were not associated with development of SAE.

As expected, we found that increased ISS, increased maximum AIS, and decreased GCS, were associated with increased odds of SAE in older adult trauma patients. These findings are consistent with prior research demonstrating that an older, complicated, more seriously injured patients have greater odds of experiencing a major complications than do a younger, simple, less seriously injured patients. (18–20, 36–41). However, we were surprised to find a different set of PECs associated with SAE and with FTR. Here, we found that age ≥ 70 and renal disease were the highest risk PECs among adult trauma patients.

While risk factors for SAE and FTR have been described for a diverse array of elective surgical patients, work in the trauma population has been much more limited. In recent paper by Bell and Zarzaur focused on patients <65 years of age also found that renal disease doubled the risk of FTR in trauma patients and also identified diabetes, congestive heart failure and history of myocardial infarction as risk factors for FTR. (14) In contrast, in our study we found no independent association with these PECs, but found that increased age, coagulopathy, liver disease, and renal disease increased the risk of FTR in trauma patients. Given that our work includes patients ranging from 16 years of age to >90 years of age, it is perhaps unsurprising that risk factors for FTR are somewhat different. We believe this work adds to the literature surrounding FTR after trauma because older adults comprise a large proportion of injured patients and this number is only expected to increase with the greying of the population. In support of the significance of including older patients in our FTR analyses, it is notable that other than renal disease, the single risk factor that increased the odds of FTR the most was age. These findings are in line with an extensive body of work which is well-summarized in a 2010 article by Scheetz (42), showing increased risk of injury severity and mortality in adults ≥ 65 (39, 42–48). However, contrary to a recent meta-analysis showing increased risk of mortality in trauma patients up to age 75 but little increased risk thereafter, our data demonstrated continued risk increases with increased age, even after age 75 (40). The fact that age was associated with higher odds of FTR than was injury mechanism or any PEC aside from renal disease highlights the vulnerability of geriatric trauma patients and suggests that there may be factors unique to increased age that puts elder patients at higher risk. Previously suggested theories linking increased age and increased mortality in trauma patients include decreased physiologic reserve (18, 49), polypharmacy (50), and overall frailty (51, 52).

Drug abuse was associated with an increased risk for SAE but is simultaneously associated with a decreased risk of FTR. Because substance abuse is more frequent among the young, we considered the possibility that a broad age category such as 16–59 might not adequately adjust for the relationship between age and substance abuse; however modelling age as a continuous variable did not attenuate this association (OR 0.2, 95% CI 0.1–0.6). Future investigations may uncover the mechanistic underpinnings for this unexpected finding.

This study has several limitations. As a single center study, our results may not be generalizable to all patient populations. Although our patient cohort had similar rates of SAE and FTR as have been found in national cohorts (22), further study will be needed to determine whether or not the findings we describe here are broadly applicable to populations at other trauma centers. As this is retrospective study of registry data, it is not possible to verify that all PECS are captured or correctly ascertained. This is a known limitation of retrospective cohort studies. However, data at our center is prospectively collected for PTOS by trained abstractors as is mandated by the Pennsylvania Trauma Systems Foundation. The training of our abstractors generally allows for discrimination between conditions present on admission and those occurring as a result of injury, but any questions which arrive are resolved through queries to clinical providers. Thus, while we cannot be certain no bias exists secondary to misclassification of exposures, we believe that the effect of such a bias is likely to be small. It is additionally possible that socioeconomic factors which limit access to care may influence the diagnosis of PECs, leading to bias in some subgroups of patients. While our ability to perform rigorously address this issue was limited secondary to lack of reliable socioeconomic data, we did not find telling differences in the numbers of PECs by insurance status. Finally, we do not have a variable which reliably permits us to capture withdrawal of care and thus some cases which meet the definition of FTR (death after a SAE) may not reflect the intended spirit of the metric. However, the relationship between withdrawal of care and FTR is may not always be straightforward, as mounting SAE burden may lead to changes in the goal of care. It is therefore the case that whether or not a case represents a ‘true’ FTR case is in some sense dependent upon the intent of the care and when that intention is measured, and further research will be required to address this issue.

This study focused on the morbidity and mortality related to SAE and FTR and we believe our findings highlight a subset of patients in whom future efforts to reduce mortality related to SAE should be targeted. While the specific interventions that may prove useful are as yet unknown, it is possible that heightened vigilance surrounding this cohort could lead to improved outcomes. For instance, based on our findings patients with coagulopathy and liver disease could be flagged in the electronic record for increased surveillance, particularly if they develop a sentinel complication. Early and aggressive escalation of care in these patients could thereby potentially lead to reductions in FTR deaths.

Conclusions

Rates of both SAE and FTR are highest in trauma patients who have renal disease or are over age 70. Aside from renal disease, comorbidities associated with the development of SAE are not the same as those associated with FTR. This study identifying characteristics associated with increased rates of SAE and FTR in the trauma population enables future quality improvement efforts to target patients with the greatest odds of mortality secondary to failure to rescue.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

DISCLOSURES: This project was in part funded by NIH grant K12 HL-10909

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS:

Study conception and design:

Earl-Royal, Holena,

Acquisition of data:

Holena

Analysis and interpretation of data:

Earl-Royal, Hsu, Holena

Drafting of manuscript:

Earl-Royal, Kaufman, Holena

Critical revision:

Earl-Royal, Kaufman, Reilly, Wiebe, Holena

References

- 1.Haas B, Gomez D, Hemmila MR, Nathens AB. Prevention of complications and successful rescue of patients with serious complications: Characteristics of high-performing trauma centers. Journal of Trauma - Injury, Infection and Critical Care. 2011;70:575–582. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31820e75a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glance LG, Dick AW, Meredith JW, Mukamel DB. Variation in hospital complication rates and failure-to-rescue for trauma patients. Annals of Surgery. 2011;253:811–816. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318211d872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silber JH, Williams SV, Krakauer H, Schwartz JS. Hospital and patient characteristics associated with death after surgery. A study of adverse occurrence and failure to rescue. Medical Care. 1992;30:615–629. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR. A Spurious Correlation between Hospital Mortality and Complication Rates: The Importance of Severity Adjustment. Medical Care. 1997;35:OS77–OS92. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199710001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Schwartz JS, Ross RN, Williams SV. Evaluation of the complication rate as a measure of quality of care in coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;274:317–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farjah F, Backhus L, Cheng A, Englum B, Kim S, et al. Failure to rescue and pulmonary resection for lung cancer. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sammon JD, Pucheril D, Abdollah F, Varda B, Sood A, et al. Preventable mortality after common urological surgery: Failing to rescue? BJU International. 2014 doi: 10.1111/bju.12833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Williams SV, Ross RN, Sanford Schwartz J. The relationship between choice of outcome measure and hospital rank in general surgical procedures: Implications for quality assessment. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 1997;9:193–200. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/9.3.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Ross RN. Comparing the contributions of groups of predictors: Which outcomes vary with hospital rather than patient characteristics? Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1995;90:7–18. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsushima K, Schaefer EW, Won EJ, Armen SB, Indeck MC, et al. POsitive and negative volume-outcome relationships in the geriatric trauma population. JAMA Surgery. 2014;149:319–326. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.4834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glance LG, Osler TM, Mukamel DB, Meredith JW, Li Y, et al. Trends in Racial Disparities for Injured Patients Admitted to Trauma Centers. Health services research. 2013;48:1684–1703. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menendez ME, Ring D. Failure to rescue after proximal femur fracture surgery. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 2015;29:e96–e102. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arya S, Kim SI, Duwayri Y, Brewster LP, Veeraswamy R, et al. Frailty increases the risk of 30-day mortality, morbidity, and failure to rescue after elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair independent of age and comorbidities. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2015;61:324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.08.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bell TM, Zarzaur BL. The impact of preexisting comorbidities on failure to rescue outcomes in nonelderly trauma patients. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2015;78:312–317. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooks SE, Mukherjee K, Gunter OL, Guillamondegui OD, Jenkins JM, et al. Do models incorporating comorbidities outperform those incorporating vital signs and injury pattern for predicting mortality in geriatric trauma? J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:1020–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Services HaH, editor. ASPE At risk: Pre-existing conditions could affect 1 in 2 Americans. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacKenzie EJ, Morris JA, Jr, Edelstein SL. Effect of pre-existing disease on length of hospital stay in trauma patients. J Trauma. 1989;29:757–764. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198906000-00011. discussion 764-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollis S, Lecky F, Yates DW, Woodford M. The effect of pre-existing medical conditions and age on mortality after injury. J Trauma. 2006;61:1255–1260. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000243889.07090.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris JA, Jr, MacKenzie EJ, Edelstein SL. The effect of preexisting conditions on mortality in trauma patients. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;263:1942–1946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milzman DP, Boulanger BR, Rodriguez A, Soderstrom CA, Mitchell KA, et al. Pre-existing disease in trauma patients: a predictor of fate independent of age and injury severity score. J Trauma. 1992;32:236–243. discussion 243-234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergeron E, Rossignol M, Osler T, Clas D, Lavoie A. Improving the TRISS methodology by restructuring age categories and adding comorbidities. J Trauma. 2004;56:760–767. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000119199.52226.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ingraham A, Xiong W, Hemmila M, Shafi S, Goble S, et al. The attributable mortality and length of stay of trauma-related complications: a matched cohort study. Ann Surg. 2010;252:358–362. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e623bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khuri SF. The NSQIP: A new frontier in surgery. Surgery. 2005;138:837–843. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osler T, Glance LG, Hosmer DW. Complication-associated mortality following trauma: A population-based observational study. Archives of Surgery. 2012;147:152–158. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khuri SF, Henderson WG, DePalma RG, Mosca C, Healey NA, et al. Determinants of long-term survival after major surgery and the adverse effect of postoperative complications. Ann Surg. 2005;242:326–341. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000179621.33268.83. discussion 341-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ortman SCaJ. In: Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. Bureau UC, editor. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saillant NN, Earl-Royal E, Pascual JL, Allen SR, Kim PK, et al. The relationship between processes and outcomes for injured older adults: a study of a statewide trauma system. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00068-015-0586-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foundation PTS Pennsylvania Outcomes and Performance Improvement Measurement System (POPIMS) Operations Manual. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghaferi AA, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Hospital Characteristics Associated with Failure to Rescue from Complications after Pancreatectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonzalez AA, Dimick JB, Birkmeyer JD, Ghaferi AA. Understanding the volume-outcome effect in cardiovascular surgery: The role of failure to rescue. JAMA Surgery. 2014;149:119–123. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arlow RL, Moore DF, Chen C, Langenfeld J, August DA. Outcome-volume relationships and transhiatal esophagectomy: Minimizing "failure to rescue". Annals of Surgical Innovation and Research. 2014;8 doi: 10.1186/s13022-014-0009-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ilonzo N, Egorova NN, McKinsey JF, Nowygrod R. Failure to rescue trends in elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair between 1995 and 2011. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.08.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Siddiq Z, Arend R, Neugut AI, et al. Failure to rescue as a source of variation in hospital mortality for ovarian cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:3976–3982. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Cheung RB, Sloane DM, Silber JH. Educational Levels of Hospital Nurses and Surgical Patient Mortality. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:1617–1623. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silber JH, Kennedy SK, Even-Shoshan O, Chen W, Mosher RE, et al. Anesthesiologist board certification and patient outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1044–1052. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200205000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perdue PW, Watts DD, Kaufmann CR, Trask AL. Differences in mortality between elderly and younger adult trauma patients: Geriatric status increases risk of delayed death. Journal of Trauma - Injury, Infection and Critical Care. 1998;45:805–810. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199810000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tornetta P, Iii, Mostafavi H, Riina J, Turen C, Reimer B, et al. Morbidity and mortality in elderly trauma patients. Journal of Trauma - Injury, Infection and Critical Care. 1999;46:702–706. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199904000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adams SD, Cotton BA, McGuire MF, Dipasupil E, Podbielski JM, et al. Unique pattern of complications in elderly trauma patients at a Level i trauma center. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2012;72:112–118. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318241f073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morris JA, Jr, MacKenzie EJ, Damiano AM, Bass SM. Mortality in trauma patients: the interaction between host factors and severity. J Trauma. 1990;30:1476–1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hashmi A, Ibrahim-Zada I, Rhee P, Aziz H, Fain MJ, et al. Predictors of mortality in geriatric trauma patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:894–901. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182ab0763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pellicane JV, Byrne K, DeMaria EJ. Preventable complications and death from multiple organ failure among geriatric trauma victims. J Trauma. 1992;33:440–444. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199209000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheetz LJ. Prehospital factors associated with severe injury in older adults. Injury. 2010;41:886–893. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Champion HR, Copes WS, Buyer D, Flanagan ME, Bain L, et al. Major trauma in geriatric patients. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:1278–1282. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.9.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grossman MD, Miller D, Scaff DW, Arcona S. When is an elder old? Effect of preexisting conditions on mortality in geriatric trauma. Journal of Trauma - Injury, Infection and Critical Care. 2002;52:242–246. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Newgard CD. Defining the "older" crash victim: the relationship between age and serious injury in motor vehicle crashes. Accid Anal Prev. 2008;40:1498–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Augenstein J, Perdeck E, Stratton J, Digges K, Bahouth G. Characteristics of crashes that increase the risk of serious injuries. Annu Proc Assoc Adv Automot Med. 2003;47:561–576. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Demetriades D, Sava J, Alo K, Newton E, Velmahos GC, et al. Old age as a criterion for trauma team activation. J Trauma. 2001;51:754–756. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200110000-00022. discussion 756–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scheetz LJ. Differences in survival, length of stay, and discharge disposition of older trauma patients admitted to trauma centers and nontrauma center hospitals. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2005;37:361–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McMahon DJ, Schwab CW, Kauder D. Comorbidity and the elderly trauma patient. World J Surg. 1996;20:1113–1119. doi: 10.1007/s002689900170. discussion 1119–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Justiniano CF, Coffey RA, Evans DC, Jones LM, Jones CD, et al. Comorbidity-polypharmacy score predicts in-hospital complications and the need for discharge to extended care facility in older burn patients. J Burn Care Res. 2015;36:193–196. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown NA, Zenilman ME. The impact of frailty in the elderly on the outcome of surgery in the aged. Advances in Surgery. 2010;44:229–249. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Joseph B, Pandit V, Zangbar B, Kulvatunyou N, Hashmi A, et al. Superiority of frailty over age in predicting outcomes among geriatric trauma patients: a prospective analysis. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:766–772. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.