Abstract

Biased stress appraisals critically relate to the origins and temporal course of many—perhaps most—forms of psychopathology. We hypothesized that aberrant stress appraisals are linked directly to latent internalizing and externalizing traits that, in turn, predispose to multiple disorders. A high-risk community sample of 815 adolescents underwent semistructured interviews to assess clinical disorders and naturalistic stressors at ages 15 and 20. Participants and blind rating teams separately evaluated the threat associated with acute stressors occurring in the past year, and an appraisal bias index (i.e., discrepancy between subjective and team-rated threat) was generated. A two-factor (Internalizing and Externalizing) latent variable model provided an excellent fit to the diagnostic correlations. After adjusting for the covariation between the factors, adolescents’ threat overestimation prospectively predicted higher standing on Internalizing, whereas threat underestimation prospectively predicted elevations on Externalizing. Cross-sectional analyses replicated this pattern in early adulthood. Appraisals were not related to the residual portions of any diagnosis in the latent variable model, suggesting that the transdiagnostic dimensions mediated the connections between stress appraisal bias and disorder entities. We discuss implications for enhancing the efficiency of emerging research on the stress response and speculate how these findings, if replicated, might guide refinements to psychological treatments for stress-linked disorders.

Keywords: appraisal, externalizing, internalizing, stress reactivity, transdiagnostic

Environmental stressors precede many cases of mental disorder. Both acute stressful life events and chronically adverse conditions can shape the onset, temporal course, and consequences of depressive, bipolar, anxiety, substance use, antisocial, and psychotic disorders (e.g., Conway, Rutter, & Brown, 2016; Hammen, 2005; Hlastala et al., 2000; Kim, Conger, Elder, & Lorenz, 2003; Monroe, Slavich, & Georgiades, 2014; Myin-Germys & van Os, 2007; Sinha, 2001). Thus, comprehensive models of the origins and treatment of psychopathology require consideration of an individual’s stressful environments and the mechanisms that link such experiences to symptoms and disorders.

Clearly, however, serious stressors do not invariably trigger psychopathology. Life stress research has revealed diverse trajectories of vulnerability and resilience in response to adversity. Adaptive stress responses, mediated by homeostatic biological and psychological systems, are common. For instance, although a significant stressor precedes most depressive episodes, only one in five of those exposed to acute stress becomes depressed (Brown & Harris, 1978). Pathological stress responses, in contrast, often include hyperbolic cognitive-emotional reactions instigated by misrepresentations of stressor impact and meaning. That is, according to a large body of evidence on emotion regulation processes (e.g., Gross & Jazaieri, 2014; Joorman & Vanderlind, 2014), faulty appraisals of stressor impact are largely responsible for initiating maladaptive responses.

The most extensively studied instances of stress appraisal bias involve depressed and anxious populations, consistent with Beck’s (1976) classic cognitive theory, which posits that a tendency to distort the significance of stressful situations—exaggerating threat, depletion, and loss—sets the stage for, and later sustains, internalizing symptoms. Over recent years, a vast amount of research has found evidence for a variety of attentional, interpretive, and memory biases associated with depression and anxiety that are relevant to stress appraisal. Biases include preferential attention to negative information, negative inferential style, overgeneral autobiographical memory, and difficulties disengaging from negative information (e.g., reviews by Gotlib & Joorman, 2010; Joorman & Vanderlind, 2014; Mathews & MacLeod, 2005; Yoon & Zinbarg, 2008). These biases can accentuate the negative aspects of life circumstances, creating and prolonging distressing emotions.

Less research has explored biased appraisals of personal stressors as they relate to externalizing disorders. In contrast to amplified stress responses observed in internalizing populations, antisocial behavior and substance use disorders generally feature hyposensitivity to threatening, emotional, or stressful circumstances (e.g., Birbaumer et al., 2005; Dawes et al., 1999; Raine, Venables, & Williams, 1990; Syngelaki, Fairchild, Moore, Savage, & van Goozen, 2013). Some evidence suggests that malfunctioning inhibitory mechanisms account for this blunted reactivity (e.g., Krueger & South, 2009). For instance, inhibitory control deficits in the face of probable punishment are commonly detected among people at risk for externalizing problems (reviewed in Byrd, Loeber, & Pardini, 2014; Frick & Dickens, 2006). Similarly, a variety of studies document that impulsive and aggressive individuals experience less negative emotional arousal when encountering potential threat because they assess dangerous or stressful situations as nonthreatening (De Vries-Bouw et al., 2011). Thus, risky and antisocial behaviors are theorized to be more common in these populations because they are not deterred by fear of punishment or negative outcomes (Raine et al., 1990).

Together, these lines of research signal discriminant validity between, but not within, internalizing and externalizing disorder domains. That is, stress overreactions pervade the anxiety and depressive disorders, whereas insensitivity to stress characterizes diverse antisocial behavior and substance use conditions. This lack of discriminant validity among commonly co-occurring syndromes is the norm in many research areas—not just research on the stress response—and it has propelled the shift toward the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) initiative and other transdiagnostic models of psychopathology. One possible explanation for this pattern of observations is that stress reactivity processes, such as stress appraisal, are directly related to a small set of core psychopathological traits that underpin multiple disorders (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema & Watkins, 2011). From this perspective, diagnostic entities (e.g., panic disorder, persistent depressive disorder) are manifestations of underlying transdiagnostic traits, and they are not expected to have strong associations with clinical outcomes independent of those basic transdiagnostic dimensions (Krueger & Markon, 2006).

There are two goals of the present paper. First, we present a method of measuring characteristic ways of appraising stressful life events that is based on individuals’ own recent stressors. Second, we test the hypothesis that transdiagnostic dimensions underlying internalizing disorders and externalizing disorders are each associated with aberrant stress appraisals, but in markedly different ways.

Why do we propose a measure based on naturally occurring stressors? We argue that much of the functional impairment accompanying psychological disorders results from maladaptive emotions and behaviors that stem from misappraisals of life circumstances. In the real world, the ability to appropriately cope with challenging events and situations requires accurate interpretation of the likelihood, meaning, and consequences of actual circumstances; these may be difficult to validly reproduce in the laboratory setting. We operationalize appraisal bias as the discrepancy between objective, contextually-informed ratings of the severity of participants’ recent stressful life events as rated by blind, independent raters on the one hand, and participants’ subjective judgments of stressor severity on the other. In an earlier study, Espejo, Hammen, and Brennan (2012) reported that youth whose stress appraisals were more negative than those of the objective rating team were at heightened risk for new onsets of depressive and anxiety disorders over late adolescence. In the current study, we extend this method to create a bipolar appraisal bias construct, in the sense that misperceptions can reflect either over- or underestimation of stressor impact relative to objective standards. The stress assessment is based on a gold standard interview method of evaluating occurrence and impact of stress based on the context in which it occurs (Hammen, in press; see also Monroe, 2008).

Construct Validity of a Quantitative Transdiagnostic Model of Mental Disorders

We rely on recent developments in the quantitative modeling of the latent structure of psychopathology to relate appraisal bias to transdiagnostic traits. Structural research on the internalizing and externalizing domains can be traced back to Achenbach’s (e.g., Achenbach, 1966) latent variable modeling of child behavior problems. In a pair of highly influential studies, Krueger and his collaborators (Krueger, 1999; Krueger, Caspi, Moffitt, & Silva, 1998) extended this modeling framework by analyzing diagnostic correlations from large community samples of adults. Paralleling Achenbach’s early findings, Krueger et al. uncovered an Internalizing factor underlying the anxiety and depressive disorders and an Externalizing factor underlying the antisocial behavior and substance use disorders. This two-factor configuration has demonstrated impressive consistency across several large-scale epidemiological studies (reviewed in Eaton, Rodriguez-Seijas, Carragher, & Krueger, 2015). Additionally, research has shown the Internalizing and Externalizing factors to be stable over time and present across a variety of cultures and age ranges (Krueger et al., 1998; Krueger, Chentsova-Dutton, Markon, Goldberg, & Ormel, 2003).

The available research on the latent structure of disorders summarized above has been largely descriptive. Expressed in latent variable modeling terminology, the focus has been on the measurement model, as compared to structural relations of the transdiagnostic dimensions with external constructs. The next phase, which is just beginning, will evaluate the predictive, convergent, and discriminant validity of the Internalizing and Externalizing dimensions. The results of these investigations will determine the value of the proposed transdiagnostic model as a research and diagnostic tool. Specifically, strong correlations between the transdiagnostic dimensions and biobehavioral outcomes would validate the Internalizing and Externalizing dimensions as useful levels of analysis (Krueger & Markon, 2006). On the other hand, weak correlations—either in absolute terms or relative to effects of observed diagnostic categories—of the transdiagnostic dimensions with external constructs would suggest limited utility.

A small group of existing studies has investigated the construct validity of the Internalizing and Externalizing dimensions. This research evaluates the extent to which the transdiagnostic dimensions explain previously observed associations between psychosocial factors and individual diagnostic categories. For instance, South, Krueger, and Iacono (2011) found that the association between marital problems and individual disorders (e.g., major depression) was mediated by the overarching Internalizing and Externalizing traits. That is, after adjusting for the transdiagnostic dimensions, marital discord was unrelated to specific mental disorders (cf. Krueger & Piasecki, 2002). Analogous patterns of results have been reported in other substantive areas, such as childhood maltreatment, intergenerational transmission of depression, and gender differences in psychopathology (Eaton et al., 2012; Keyes et al., 2012; Starr, Conway, Hammen, & Brennan, 2014). Findings from this line of research carry potentially significant implications for research design strategies. For instance, in the current research context, if aberrations in stress responding are indeed traced to cross-cutting psychopathological traits, as opposed to specific diagnoses, then studies designed to compare a single disorder to a healthy control group might be considered inefficient. Instead, the maximally informative investigation would examine correlations between stress responses and relevant transdiagnostic dimensions, which presumably represent the driving forces behind prior evidence of association between categorical disorders and the stress response.

Present Study

We applied the quantitative model of comorbidity to understand the relationship between dysfunctional stress appraisals and common mental disorders. We focused on biased appraisals of naturalistic stressors, which, as mentioned above, are conceptually related to several cognitive processes previously investigated in the context of internalizing disorders. Exploiting the hierarchical organization of the quantitative model (see Krueger & Piasecki, 2002), we examined stress appraisal bias in relation to transdiagnostic and diagnosis-specific components of a latent variable model of mental disorders.

The appraisal bias index was computed at two time periods in a longitudinal study: mid-adolescence (age 15) and young adulthood (age 20). We first examined the age 15 bias as a predictor of new onsets of disorder occurring between ages 15 and 20 based on the hypothesis that cognitive bias may serve as a developmental antecedent to psychopathology. We then examined the age 20 bias as a correlate of lifetime diagnoses up to age 20. Evidence from both preclinical and human research suggests that stress reactivity peaks in adolescence, and that stress-related disorders in adolescence and early adulthood shape the trajectory of psychopathology and psychosocial functioning long into adulthood (e.g., Dahl & Gunnar, 2009; Ge, Conger, & Elder, 2001; Rohde, Lewinsohn, Klein, Seeley, & Gau, 2013). Thus, cognitive processes implicated in the stress response during this time period are theorized to have enduring, clinically significant consequences.

We hypothesized that overestimations of event impact would predict higher standing on the Internalizing factor given prior findings of hyperactive biological and cognitive-emotional stress reactivity mechanisms in anxiety and depressive disorders (e.g., Craske et al., 2009; Mathews & MacLeod, 2005). In contrast, we expected that Externalizing would be associated with underestimation of event impact. As briefly reviewed above, externalizing disorders are related to hypoactivation of several stress response systems, which might contribute to a discounting of the possible negative consequences of stressful situations (e.g., van Leeuwen, Rodgers, Gibbs, & Chabrol, 2014). Finally, we hypothesized that any associations between individual diagnoses and appraisal bias would be comparatively small after statistically adjusting for the effects of transdiagnostic dimensions.

Methods

Participants

Eight hundred fifteen mothers and their 15-year-old children (412 males) were recruited from an ongoing birth cohort study of health and social outcomes, originally consisting of 7,223 pregnant women who gave birth between 1981 and 1984 in Brisbane, Australia (Keeping et al., 1989). Women were recruited to represent a wide range of depressive experiences based on scores on a questionnaire measure of depressive symptoms administered four times between pregnancy and child age five (Delusions-Symptoms-States-Inventory; Bedford & Foulds, 1978). Depression diagnoses were later confirmed by diagnostic interview based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1995) at youth age 15; 358 mothers had a lifetime diagnosis of major depressive episode and/or dysthymic disorder, and 457 were never depressed. The families were predominantly lower middle/working class and 91.4% were Caucasian (3.6% Asian, 5% other). Sixty-seven percent of the mothers were currently married to the father of the child, 12% were currently not married, and 21% were married to someone other than the biological father. Further details of sample selection are reported by Hammen and Brennan (2001).

At age 20, families were re-contacted for follow-up and, among those located, 705 youth agreed to participate (86.5%; 342 males). There were no statistically significant differences in the rates of participation at age 20 compared to age 15 by maternal depression status by youth age 15, χ2(1) = 3.60, p = .06, or youth depressive diagnoses by 15, χ2(1) = 0.25, p = .25. However, males were less likely retained at age 20, χ2(1) = 8.71, p < .01.

Procedures

At ages 15 and 20, the youth and their mothers separately completed interviews and questionnaires in their home. All participants completed informed consent (assent) procedures at both time points, and procedures were approved by institutional review boards of the University of Queensland, Emory University, and the University of California, Los Angeles.

Measures

Youth diagnoses

At age 15, youth current and lifetime mental disorders were ascertained using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Revised for DSM-IV (K-SADS-E; Orvaschel, 1995), administered separately to the parent and the child by interviewers blind to mothers’ depression status. Diagnostic decisions were reviewed by the clinical rating team with best-estimate judgments based on all available information. In the current sample, weighted kappas for youth diagnoses were .82 for current depressive diagnoses (major depressive disorder or dysthymia) or subclinical depression, and .73 for past depressive diagnoses or subclinical depression. Reliabilities for current anxiety, substance use, disruptive behavior (conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder), and “other” (primarily eating) disorders ranged from .67 to 1.0, with a mean of .82; reliabilities for past diagnoses ranged between .72 and 1.0, with a mean of .81.

At the age 20 follow-up, youth were administered the SCID, which covered the 5-year interval since the age 15 assessment. Interrater reliabilities (i.e., kappa coefficients) for current diagnoses were .83 for depressive disorders, .94 for anxiety disorders, and .79 for substance abuse disorders. The corresponding kappa values for past disorders were .89, .89, and .96, respectively.

Stressful life events

At age 15 and age 20, the UCLA Life Stress Interview (LSI; Hammen & Brennan, 2001; Hammen et al., 1987) was administered to assess occurrence and severity of stressful life events in the past 12 months. Similar to the Life Events and Difficulties Schedules (Brown & Harris, 1978), the LSI is a semi-structured interview with two defining characteristics. First, following identification and careful dating of each negative life event, the event is probed to determine the factual elements of the context in which it occurred in order to fully define the impact and meaning of the event for that individual. Second, event impact/severity is evaluated by an independent rating team following presentation of a written narrative of each event and its context. The ratings of severity on a 5-point scale (from no negative impact to extremely negative impact) are assigned by consensus discussion. The interviewer elicits the individual’s subjective appraisal of each event on a 5-point scale (from no negative impact to extremely negative impact), but this information is not available to the rating team. Various studies have reported on the reliability and validity of the LSI for acute life events (Hammen & Brennan, 2001; Hammen, Brennan, Keenan-Miller, & Herr, 2008; Hammen, Kim, Eberhart, & Brennan, 2009). In the current study, interrater reliability estimates between independent rating teams for stressor severity were .92 at .95 at age 15 and age 20, respectively. Additionally, previous research has documented good test-retest reliability of subjective ratings of stressor impact (Espejo et al., 2011).

The appraisal bias score for each individual was based on established methods for comparing subjective and objective ratings (Cole, Martin, Peake, Seroczynski, & Hoffman, 1998; De Los Reyes & Prinstein, 2004; Krackow & Rudolph, 2008). Mean subjective severity rating scores were regressed on mean objective severity rating scores in the full sample, yielding an index of subjective perceptions of stressfulness that adjusts for objective levels of threat. The standardized residuals constitute the outcome variables in the present analyses, with higher scores representing perceptions of more negative impact (Conway et al., 2012).1

Data Analytic Plan

Age 15 Appraisal Bias

We first examined the prospective association between appraisal bias at age 15 and subsequent new onsets of psychopathology (hereafter called the prospective model). That is, the transdiagnostic outcomes in this analysis were defined by diagnoses occurring for the first time between the age 15 and age 20 (inclusive) assessments. Indicators of the Internalizing factor were major depressive disorder (MDD), dysthymia (DYS), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder (PAN), social anxiety disorder (SOC), specific phobia (SPEC), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) diagnoses, whereas Externalizing indicators were alcohol abuse or dependence (ALC), and drug abuse or dependence (DRUG) diagnoses. Conduct disorder (COND) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) were assessed during this period, but excluded as factor indicators due to low incidence during this period (1 new onset of COND and 0 of ODD). (The prevalence of all disorders prior to age 15 was too low to permit similar latent variable analysis of disorders that onset before the age 15 assessment.)

The prospective model analyses proceeded in three parts:

-

(i)

We compared the correlated two-factor model to two other configurations—labeled the three-factor model and the bifactor model—of common mental disorders supported in prior structural research. In the three-factor model, the Internalizing factor bifurcated into Distress and Fear subfactors, an arrangement that has been found to fit in some samples but not others (Kessler et al., 2011; Krueger & Markon, 2006). The Distress subfactor was defined by MDD, DYS, GAD, and PTSD, whereas the Fear subfactor was defined by PAN, SOC, OCD, and SPEC (see Watson, 2005). In the bifactor model, each diagnosis loaded onto a superordinate General Psychopathology factor (termed the p-factor by Caspi et al., 2014) and onto one specific factor representing Internalizing or Externalizing. This model has been found to fit diagnostic- and symptom-based data well in several prior studies (e.g., Caspi et al., 2014; Laceulle, Vollebergh, & Ormel, 2015; Lahey et al., 2012; Tackett et al., 2013).

-

(ii)

We regressed the transdiagnostic factors from the best fitting model onto the age 15 appraisal bias index. Additionally, given the moderate correlation between Internalizing and Externalizing observed here (see Results) and in prior research, we carried out supplementary regressions to determine the association between bias and Internalizing while controlling for variation on Externalizing (and vice versa). This step was based on previous findings that indicated the Internalizing and Externalizing factors exhibited different correlations with external constructs once their overlap was partialled out (e.g., Caspi et al., 2014).

-

(iii)

Modification indices from the regressions in (ii) were then inspected to determine whether estimating any paths from age 15 appraisal bias to diagnostic residual terms would improve model fit. Following prior conventions (Keyes et al., 2012), we set a modification index threshold of 3.84 (i.e., critical chi-square value for expected model improvement corresponding to a .05 alpha level) to evaluate for the presence of statistically significant diagnosis-specific associations. Any statistically significant residual associations would indicate that appraisal bias predicted unique portions of manifest disorders while holding constant levels of the transdiagnostic factor of which the diagnosis is an indicator.

Age 20 Appraisal Bias

We next examined the correlations between age 20 appraisal bias and lifetime psychopathology up to age 20 (concurrent model). Transdiagnostic outcomes in this analysis were defined by current or past disorders documented at the age 20 assessment point (i.e., combining information from the age 15 K-SADS-E evaluation and the age 20 SCID evaluation). The factor indicators were the same as above, except that COND and ODD were included as indicators of the Externalizing factor. We followed the same sequence of analyses as the prospective model:

-

(iv)

We compared the two-factor, three-factor, and bifactor models for lifetime disorders.

-

(v)

We regressed the transdiagnostic factors from the best fitting model onto the age 20 appraisal bias index. To statistically control for the overlap between transdiagnostic dimensions, we then covaried Externalizing in the regression of Internalizing on appraisal bias and, likewise, covaried Internalizing when regressing Externalizing on appraisal bias.

-

(vi)

We inspected modification indices from the regressions in (v) to determine whether there were any statistically significant disorder-specific associations with age 20 appraisal bias.

To summarize, this latter set of analyses examined the correlations between appraisal bias at age 20 and lifetime (i.e., ages 0-20) history of mental disorders. These analyses were considered a test of concurrent validity, whereas the prospective model was considered a test of predictive validity. Results from these two models allowed us to determine whether appraisal bias at age 20 showed the same pattern of associations with psychopathology as bias at age 15 despite variation across the different time periods in the rates of disorder and latent variable model indicators.

Data were analyzed in Mplus (version 7.11; Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2014) using the weighted least squares means and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator. We evaluated model goodness of fit with the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the weighted root mean square residual (WRMR). Acceptable fit was defined according to guidelines offered by Hu and Bentler (1999): RMSEA values close to 0.06 or below, CFI and TLI values close to .95 or above, and WRMR values close to 1.00 or below. We also judged model fit on the basis of interpretability of parameter estimates and localized areas of strain (i.e., modification indices).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 displays lifetime (to age 20) diagnostic frequencies and correlations. As expected, internalizing disorders were more often comorbid with each other than with externalizing disorders (and vice versa). Rates of new disorder onsets after age 15 were as follows: 148 MDD, 21 DYS, 43 GAD, 22 PAN, 114 SOC, 77 SPEC, 36 PTSD, 17 OCD, 190 ALC, and 164 DRUG.

Table 1. Correlations among Lifetime Mental Disorders and Appraisal Bias Indices.

| MDD | DYS | GAD | PAN | SOC | SPEC | PTSD | OCD | CON | ODD | ALC | DRUG | BIAS15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDD | |||||||||||||

| DYS | .47c | ||||||||||||

| GAD | .56c | .38c | |||||||||||

| PAN | .60c | .51c | .52c | ||||||||||

| SOC | .29c | .25b | .46c | .25a | |||||||||

| SPEC | .13 | .16 | .32c | .22 | .25c | ||||||||

| PTSD | .58c | .37c | .36c | .41c | .09 | .25b | |||||||

| OCD | .04 | .01 | .25 | .24 | −.01 | −.02 | .30a | ||||||

| CON | .22 | .31a | .08 | .28 | .18 | .17 | −.04 | −.01 | |||||

| ODD | .30b | .03 | .29a | .10 | .42c | −.09 | .31a | .31 | −.02a | ||||

| ALC | .18b | .01 | .23b | .12 | .22b | −.04 | .19a | .18 | .42c | .42c | |||

| DRUG | .20b | .23b | .21a | .31b | .18a | −.03 | .30c | .22 | .63c | .35b | .62c | ||

| BIAS15 | .24c | .12a | .22c | .15 | .13a | .08 | .23b | .00 | .15 | .01 | −.03 | −.09 | |

| BIAS20 | .28c | .16a | .36c | .22a | −.02 | .08 | .26c | .01 | −.04 | .16 | −.01 | −.06 | .16c |

| N (%) | 220 (27) | 71 (9) | 56 (7) | 24 (3) | 144 (18) | 110 (13) | 48 (6) | 21 (3) | 21 (3) | 22 (3) | 198 (24) | 177 (22) | — |

Note. MDD = major depressive disorder; DYS = dysthymia; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; PAN = panic disorder; SOC = social phobia; SPEC = specific phobia; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; OCD = obsessive-compulsive disorder; CON = conduct disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; ALC = alcohol abuse/dependence; DRUG = drug abuse/dependence; BIAS15 = age 15 stress appraisal bias; BIAS20 = age 20 stress appraisal bias. Correlations among diagnoses are tetrachoric correlations. N = number of participants qualifying for a diagnosis.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Table 1 also shows that a history of internalizing disorder—with the exception of specific phobia—generally was associated with appraisal bias (i.e., overestimation of impact) at both assessment waves. In contrast, externalizing diagnoses were largely unrelated to appraisal bias (mean r = .03).

Latent Structure of Mental Disorders

Prospective Model

The initial correlated two-factor model did not offer acceptable fit to the data, χ2(34) = 57.85, p = .01; CFI =.90; TLI = 0.86; RMSEA = 0.03; WRMR = 0.91. The factor loadings of all indicators (range: .40-.77) were statistically significant at the .001 alpha level, except for specific phobia (λ = .21, p < .05) and OCD (λ = .34, p = .08). We removed these two diagnoses from subsequent iterations of the prospective model. The revised two-factor model (i.e., without SPEC and OCD) yielded a much better fit to the data, χ2(19) = 27.96, p = .08; CFI =.97; TLI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.03; WRMR = 0.77. The correlation between the Internalizing and Externalizing factors in this revised model was .43 (p < .001).

Our attempt to fit a hierarchical three-factor model, in which a second-order Internalizing factor bifurcated into Distress and Fear subfactors, produced an improper solution. Specifically, the standardized factor loading of Fear on Internalizing was greater than unity. Ad hoc inspection of an oblique three-factor model, in which correlations between first-order Fear, Distress, and Externalizing factors were freely estimated, revealed a correlation greater than one between Fear and Distress. We concluded that Fear and Distress dimensions could not be meaningfully distinguished in these data. Similarly, attempts to fit the bifactor model did not produce an interpretable solution (i.e., negative variance estimates for the specific factors). Thus, the two-factor measurement model was applied in subsequent structural analyses.

Concurrent Model

The two-factor model fit the data well, χ2(53) = 75.56, p = .02; CFI =.96; TLI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.02; WRMR = 0.92. The factor loadings of all indicators (range: .42-.82) were statistically significant at the .001 alpha level, except for OCD (λ = .25, p = .09). We therefore omitted OCD from subsequent models. A revised two-factor model (i.e., excluding OCD) produced a nearly identical pattern of factor loadings and equivalent fit to the data, χ2(43) = 64.43, p = .02; CFI =.96; TLI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.02; WRMR = 0.93. The correlation between the Internalizing and Externalizing factors in this revised model was .39 (p < .001).

Attempts to fit more complicated structural models were unsuccessful for the same reasons reported for the prospective model above. Thus, the two-factor configuration was applied in structural analyses involving the concurrent model as well.

Transdiagnostic and Diagnosis-Specific Associations with Stress Appraisal Bias

Prospective Model

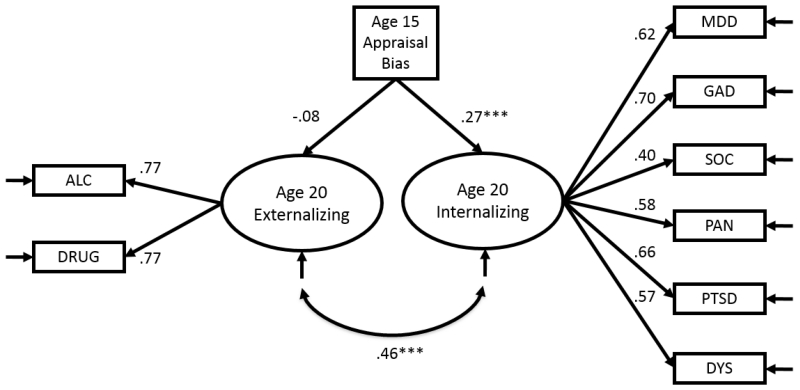

Internalizing and Externalizing factors were regressed simultaneously on age 15 appraisal bias. As shown in Figure 1, bias was positively related to Internalizing (b = 0.17, SE = 0.04, p < .001, β = .27, f2 = .07) and negatively, though non-significantly, related to Externalizing (b = −0.07, SE = 0.05, p = .15, β = −.08, f2 = .01). Next, Internalizing was regressed on age 15 appraisal bias while statistically controlling for variation in Externalizing (and vice versa). As mentioned above, this step was intended to partial out overlap among the transdiagnostic factors, essentially computing a partial correlation between appraisal bias and each factor. Holding Externalizing constant, the positive effect of bias on Internalizing was even stronger (b = 0.19, SE = 0.04, p < .001, β = 0.30). In contrast, after adjusting for Internalizing, the appraisal bias was significantly associated with Externalizing but in the opposite direction (b = −0.17, SE = 0.05, p < .01, β = −.21). The direction of this effect indicated that, after accounting for the overlap between Internalizing and Externalizing, more benign perceptions of stressor impact, relative to the objective rating team, predicted higher Externalizing levels.

Figure 1.

Path diagram (with standardized path coefficients) illustrating the contrasting predictive effects of age 15 appraisal bias on Internalizing and Externalizing factors. These effects diverge further if the overlap between factors is partialled out (see main text). MDD = major depressive disorder; DYS = dysthymia; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; PAN = panic disorder; SOC = social phobia; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; ALC = alcohol abuse/dependence; DRUG = drug abuse/dependence. All factor loadings are statistically significant at the .001 alpha level. *** p < .001.

We followed up with a planned test of the equality of the magnitude of structural associations of the Internalizing versus Externalizing factors with appraisal bias. That is, we evaluated the extent to which appraisals had divergent associations with Internalizing versus Externalizing. Chi-square difference tests (performed with the DIFFTEST procedure in Mplus) indicated that model fit deteriorated significantly when the effects of Internalizing and Externalizing were constrained to equality, χ2diff(1) = 17.21, p < .001, suggesting that the size—and, indeed, the direction—of these effects was significantly different. Comparison of other model fit indices in the restricted (CFIr =.96; TLIr= 0.95; RMSEAr = 0.02) versus unrestricted (CFIu =.99; TLIu= 0.98; RMSEAu = 0.01) models corroborated this result.

We also used difference tests to examine gender as a moderator of transdiagnostic effects on stress appraisal. Non-significant Wald tests demonstrated that the associations of appraisal bias with Internalizing and Externalizing did not differ by gender, χ2diffs(1) < 2, ps > .05. Likewise, Wald tests indicated that neither maternal depression history (44% of sample) or psychiatric medication use (3.4%) moderated the effects of age 15 appraisal bias on transdiagnostic dimensions, χ2diffs(1) < 3, ps > .05. Moreover, the pattern and statistical significance of results were unaltered if any or all of these variables (i.e., gender, maternal depression, medication use) were included as a covariate (full results available from first author upon request).

In a final step, we examined the diagnosis-specific pathways between psychopathology and appraisal bias. We inspected the modification indices to determine whether age 15 appraisal bias had a statistically significant association with any residual components of individual disorders. No modification index exceeded our predetermined minimum value of 3.84. Thus, it appeared that associations between diagnostic categories and appraisal bias were accounted for by the transdiagnostic dimensions.

Concurrent Model

As above, we began by regressing the two factors simultaneously onto age 20 appraisal bias. Young adult appraisal bias was positively associated with Internalizing (b = 0.25, SE = 0.04, p < .001, β = .31, f2 = .10), but it was virtually uncorrelated with Externalizing (b = −0.02, SE = 0.04, p = .46, β = −.04, f2 = .001). To evaluate the unique relationship of appraisal bias with Internalizing, we added Externalizing as a covariate. Holding Externalizing constant, appraisal bias had a moderate, positive association with Internalizing levels (b = 0.45, SE = 0.08, p < .001, β = 0.34, f2 = .13). Analogous to our prospective model result, when adjusting for the overlap with Internalizing, a statistically significant inverse association emerged between age 20 appraisal bias and Externalizing (b = −0.13, SE = 0.04, p < .01, β = −.18, f2 = .17).

As before, a chi-square difference test confirmed that the magnitude of the association between appraisal bias and Internalizing significantly differed from (i.e., was greater than) the association between appraisal bias and Externalizing, χ2diff(1) = 29.26, p < .001 (restricted model: CFIr =.89; TLIr= 0.87; RMSEAr = 0.04; unrestricted model: CFIu =.96; TLIu = 0.94; RMSEAu = 0.03). Mirroring results from the prospective model, the connections between young adult appraisal bias and the transdiagnostic dimensions were equally strong across gender, maternal depression history, and medication status, χ2diffs(1) < 2, ps > .05. Finally, there was no evidence of statistically significant associations between age 20 appraisal bias and any diagnostic residual (i.e., no modification index value of 3.84 or greater).

Discussion

Quantitative modeling of the latent structure of mental disorders has provided compelling evidence for a transdiagnostic model anchored by Internalizing and Externalizing dimensions that underpin major forms of psychopathology. A new phase of investigation now aims to evaluate the predictive validity of the transdiagnostic dimensions to determine their applied value. That is, it remains to be seen whether transdiagnostic factors emerging from quantitative structural research actually stand to improve mental health research and treatment practices. In the present study, we examined associations of the Internalizing and Externalizing dimensions with stress appraisal bias, a cognitive risk marker for a wide array of disorders. Our data supported the discriminant validity of the transdiagnostic constructs. After adjusting for the covariation between dimensions, adolescent stress hypersensitivity was prospectively linked to higher Internalizing levels, whereas stress hyposensitivity was prospectively related to higher Externalizing levels. Further, once standing on the Internalizing and Externalizing factors was held constant, none of the constituent diagnoses were linked to appraisal bias. Cross-sectional analyses of appraisal bias and psychopathology in young adulthood revealed an identical pattern of results.

Elevation on the Internalizing dimension was associated with exaggerated cognitive responses to naturally occurring stressors. This result aligns with data from an extensive body of observational and experimental research examining the stress response in anxious and depressed populations. That is, investigators have consistently documented abnormal cognitive styles—in both subjective (e.g., attitudinal) and implicit (e.g., speeded information-processing) domains (see Gotlib & Joorman, 2010)—in anxiety and depressive disorders. Moreover, our findings concur with laboratory studies that report disruptions in on-line biological parameters of the stress response (e.g., limbic metabolism, cortisol secretion) in emotional disorders (e.g., Craske et al., 2009; Hariri, Drabant, & Weinberger, 2006). We extend these lines of research by finding cognitive distortions in response to naturally occurring, as opposed to laboratory-based, stressors among those at risk for anxiety and depression. More importantly, our results suggest that the commonalities among the various internalizing disorders drive the associations between these conditions and stress-related phenotypes.

Our analysis of the Externalizing spectrum offers a new perspective on prior studies of antisocial behavior and substance use disorders. These syndromes generally have been associated with blunted biological and psychological responses to stressful and emotional cues (e.g., Gao, Tuvblad, Schell, Baker, & Raine, 2015; Syngelaki et al., 2013). In the present study, bivariate associations between the Externalizing spectrum and stress appraisal bias revealed little evidence of hyposensitivity. However, a very different pattern of findings—wherein Externalizing was associated with appraisals that discounted the potential negative impact accompanying stressful events—emerged after adjusting for the overlap between the transdiagnostic dimensions. It is a testament to the scientific utility of the structural model that this association between the Externalizing spectrum and appraisal bias would have been overlooked if either (a) individual antisocial behavior and substance use diagnoses had been analyzed (i.e., the Externalizing factor was greater than the sum of its parts), or (b) comorbidity with Internalizing psychopathology had been neglected. The divergence in biases characterizing Internalizing and Externalizing is consistent with prior work by Caspi et al. (2014), who uncovered different psychosocial correlates of Internalizing and Externalizing traits once the overlap between these two dimensions was partialled out.

Our findings advance the growing research literature on the concurrent and predictive validity of the Internalizing and Externalizing dimensions. Prior investigations have found that variation on transdiagnostic dimensions parsimoniously accounts for associations between categorical disorders and suicide, marital distress, intergenerational transmission of psychopathology, and childhood maltreatment (e.g., Keyes et al., 2012; South et al., 2011; Starr et al., 2014). In combination with these previous studies, our findings reinforce the notion that disorders historically examined independently are, in many research contexts, better understood in terms of their common elements (Krueger & Markon, 2006). Future inquiry into the correlates (i.e., nomological network) of the transdiagnostic traits is needed to evaluate that hypothesis across various outcomes (e.g., biological, cognitive, interpersonal) and research settings. Convincing empirical evidence of the superior construct validity of transdiagnostic dimensions, relative to categorical disorders, is needed for the transdiagnostic model to gain momentum as a research and clinical tool.

If supported, the quantitative model has the potential to unify research practices and treatment protocols that traditionally have fractured along diagnostic lines. For instance, the present results suggest that future studies on stress reactivity phenotypes may benefit from focusing on transdiagnostic effects rather than comparing stress responses in one disorder category versus a healthy control group. Thus, paralleling RDoC-informed recruitment strategies (e.g., Cuthbert & Kozak, 2013), patients with any anxiety or depressive disorder might be recruited for an investigation of the Internalizing spectrum and stress responses. Aside from enhancing the efficiency of investigations, transdiagnostic models may align more closely with basic genetic, biological, and cognitive parameters that notoriously show a pattern of multifinality with respect to mental disorder categories (Ofrat & Krueger, 2012). Thus, transdiagnostic dimensions may serve as useful intermediate phenotypes in the causal chain from distal biological and cognitive processes to complex clinical syndromes.

Analogous implications follow for the treatment and prevention of psychological disorders. If closely related disorders have a common substrate, perhaps that shared pathology could be an effective target for psychological or psychotropic treatment. Ameliorating core psychopathological processes, including stress appraisal biases, theoretically could address related conditions simultaneously, enhancing the efficiency of treatment for comorbid conditions. Barlow and colleagues are leading the way in the development of a transdiagnostic program for the treatment of internalizing disorders based on quantitative models of anxiety and depressive disorder comorbidity (Barlow, Sauer-Zavala, Carl, Bullis, & Ellard, 2014; see also Reinholt & Krogh, 2014). Similarly, if certain risk factors are shown to predispose to an array of related disorders (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema & Watkins, 2011), prevention efforts might be streamlined by targeting these transdiagnostic vulnerabilities. For instance, the present results suggest indirectly that addressing the extremes of cognitive appraisals of stressful circumstances might mitigate risk for internalizing and externalizing conditions.

Our study’s contributions should be considered in the context of several limitations. First, the temporal sequencing of bias and disorder onset could be resolved only for the age 15 appraisal bias index. The conceptual status of stress appraisal bias in young adulthood as an antecedent versus correlate of psychopathology could not be determined here. More research clearly is needed to resolve the causal relationships between cognitive bias and disorder outcomes. Second, coverage of clinical disorders was limited. It is possible that the inclusion of additional, less prevalent (e.g., bipolar, psychotic, eating) disorders could alter the number and nature of transdiagnostic dimensions (e.g., Forbush & Watson, 2013) or their pattern of association with stress appraisal bias. Along these same lines, the incidence of new antisocial behavior disorders in late adolescence was too low for them to be included in prospective analyses, consistent with epidemiological data showing that these disorders typically onset prior to age 15 (Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005). As a consequence, the Externalizing factor in these analyses was limited to substance use disorders. Although it is encouraging that the prospective results were consistent with those from the cross-sectional model, which included a wider range of disorders, further work assessing a broader range of psychopathology is needed. In fact, the rates of antisocial behavior disorders were low across the study timeframe, perhaps due to recruitment procedures that overselected for maternal depression. This imbalance in the rates of Internalizing and certain Externalizing disorders may limit, to some extent, generalizability of the results.

Third, recent quantitative research has pointed out that including symptom dimensions, as opposed to diagnostic categories, as manifest indicators of latent psychopathology constructs can reveal a more nuanced transdiagnostic architecture to psychopathology (e.g., Markon, 2010; Prenoveau et al., 2010; Wright et al., 2013). Symptom-level data were not available in the present study. Thus, continuous factor indicators (e.g., a symptom-based approach) may have improved our chances of fitting more complicated factor models (e.g., three-factor model including the subdivision of Internalizing into Fear and Distress factors). Fourth, the stability of the appraisal bias index across assessment waves was lower than anticipated (r = .16). It is possible that the changing nature of stressors experienced from adolescence to adulthood, or simply normative developmental changes in stress response processes over the five years between assessment waves, contributed to the relatively low autocorrelation. We hypothesize that stress appraisal bias is a traitlike process, perhaps one that becomes more stable with age. Finally, the present study concentrated on the transition from adolescence to adulthood. It is conceivable that the latent architecture of mental disorders or associations between disorders and stress reactivity might differ across developmental epochs (e.g., Wittchen et al., 2009). Similarly, the relatively high prevalence of maternal depression may have altered the meaning or configuration of transdiagnostic factors that emerged in our analyses, relative to what might be observed in unselected samples.

In sum, we found that transdiagnostic Internalizing and Externalizing dimensions explained associations between common mental disorders and stress appraisal biases. Additionally, we provided novel evidence of discriminant validity for the transdiagnostic constructs, in that Internalizing and Externalizing were associated with distinct appraisal bias profiles. Continued empirical research into the transdiagnostic dimensions is needed to determine whether these constructs help our theories and treatments work better. Indeed, the transdiagnostic model has the potential to compete with RDoC to serve as the organizing framework for nosology, etiological research, and treatment going forward. However, persuasive evidence for its concurrent and predictive validity is needed before it can be accepted as a viable research or diagnostic tool. The present findings provide promising evidence that it can enhance the efficiency and validity of life stress research.

General Scientific Summary.

Biased perceptions of stressful or emotional events confer vulnerability to a wide array of psychological disorders. We found here that aberrant appraisals of real-world stressors directly predict liability to Internalizing and Externalizing traits, which serve as the substrate for diverse mental disorders, but in markedly different ways. Exaggerated perceptions of stressor severity predicted higher standing on the Internalizing trait—predisposing to anxiety and depression—whereas a tendency to downplay stressor impact predicted elevations on Externalizing—predisposing to antisocial behavior and substance misuse.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council, the Mater Misericordiae Mother’s Hospital in Queensland, Australia, and the National Institute of Mental Health grant R01MH52239. We thank Professor Jake Najman of the University of Queensland and MUSP colleagues William Bor, M.D., and Gail Williams, Ph.D. Special thanks to project coordinators Robyne LeBrocque, Cheri Dalton Comber, and Sascha Hardwicke.

Footnotes

In supplementary analyses, we examined whether the association between appraisal bias and transdiagnostic factors changed if the number of reported acute life events was included as a covariate. The pattern and statistical significance of results were unchanged when we adjusted for the count of acute stressors. Full results are available from the first author upon request.

References

- Achenbach TM. The classification of children’s psychiatric symptoms: A factor-analytic study. Psychological Monographs. 1966;80:1–37. doi: 10.1037/h0093906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Sauer-Zavala S, Carl JR, Bullis JR, Ellard KK. The nature, diagnosis, and treatment of neuroticism back to the future. Clinical Psychological Science. 2014;2:344–365. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. International Universities Press; New York: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Bedford A, Foulds G. Delusions-Symptoms-States Inventory of Anxiety and Depression. NFER; Windsor, England: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Birbaumer N, Veit R, Lotze M, Erb M, Hermann C, Grodd W, Flor H. Deficient fear conditioning in psychopathy: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:799–805. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.7.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris T. Social origins of depression: A study of psychiatric disorder in women. Tavistock Publications; London, England: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd AL, Loeber R, Pardini DA. Antisocial behavior, psychopathic features and abnormalities in reward and punishment processing in youth. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2014;17:125–156. doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0159-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Houts RM, Belsky DW, Goldman-Mellor SJ, Harrington H, Israel S, Moffitt TE. The p factor: One general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders? Clinical Psychological Science. 2014;2:119–137. doi: 10.1177/2167702613497473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Martin JM, Peake LG, Seroczynski AD, Hoffman K. Are cognitive errors of underestimation predictive or reflective of depressive symptoms in children: a longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:481–496. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway CC, Hammen C, Espejo EP, Wray NR, Najman JM, Brennan PA. Appraisals of stressful life events as a genetically-linked mechanism in the stress–depression relationship. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2012;36:338–347. [Google Scholar]

- Conway CC, Rutter LA, Brown TA. Chronic environmental stress and the temporal course of depression and panic disorder: A trait-state-occasion modeling approach. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2016;125:53–63. doi: 10.1037/abn0000122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Rauch SL, Ursano R, Prenoveau J, Pine DS, Zinbarg RE. What is an anxiety disorder? Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26:1066–1085. doi: 10.1002/da.20633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert BN, Kozak MJ. Constructing constructs for psychopathology: The NIMH research domain criteria. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:928–937. doi: 10.1037/a0034028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl RE, Gunnar MR. Heightened stress responsiveness and emotional reactivity during pubertal maturation: implications for psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:1–6. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawes MA, Dorn LD, Moss HB, Yao JK, Tarter RE. Hormonal and behavioral homeostasis in boys at risk for substance abuse. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 1999;55:165–176. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Prinstein MJ. Applying depression distortion hypotheses to the assessment of peer victimization in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:325–335. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries‐Bouw D, Popma A, Vermeiren R, Doreleijers TA, Van De Ven PM, Jansen L. The predictive value of low heart rate and heart rate variability during stress for reoffending in delinquent male adolescents. Psychophysiology. 2011;48:1597–1604. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton NR, Keyes KM, Krueger RF, Balsis S, Skodol AE, Markon KE, Hasin DS. An invariant dimensional liability model of gender differences in mental disorder prevalence: evidence from a national sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121:282–288. doi: 10.1037/a0024780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton NR, Rodriguez-Seijas C, Carragher N, Krueger RF. Transdiagnostic factors of psychopathology and substance use disorders: a review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2015;50:171–182. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-1001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espejo EP, Ferriter CT, Hazel NC, Keenan-Miller D, Hoffman LR, Hammen C. Predictors of subjective ratings of stressor severity: The effects of current mood and neuroticism. Stress and Health. 2011;27:23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Espejo EP, Hammen C, Brennan PA. Elevated appraisals of the negative impact of naturally occurring life events: a risk factor for depressive and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:303–315. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9552-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, D.C.: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Forbush KT, Watson D. The structure of common and uncommon mental disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2013;43:97–108. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Dickens C. Current perspectives on conduct disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2006;8:59–72. doi: 10.1007/s11920-006-0082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Tuvblad C, Schell A, Baker L, Raine A. Skin conductance, fear conditioning impairments and aggression: A longitudinal study. Psychophysiology. 2015;52:288–295. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Conger RD, Elder GH. Pubertal transition, stressful life events, and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:404–417. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Joormann J. Cognition and depression: current status and future directions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:285–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Jazaieri H. Emotion, emotion regulation, and psychopathology: An affective science perspective. Clinical Psychological Science. 2014;2:387–401. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Depression and stressful environments: Identifying gaps in conceptualization and measurement. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2015.1134788. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Brennan PA. Depressed adolescents of depressed and nondepressed mothers: Tests of an interpersonal impairment hypothesis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:284–294. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Brennan P, Keenan-Miller D, Herr N. Early onset recurrent subtype of adolescent depression: Clinical and psychosocial correlates. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:433–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Gordon D, Burge D, Adrian C, Jaenicke C, Hiroto D. Maternal affective disorders, illness, and stress: Risk for children’s psychopathology. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;144:736–741. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.6.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Kim E, Eberhart N, Brennan P. Chronic and acute stress and the prediction of major depression in women. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26:718–723. doi: 10.1002/da.20571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Drabant EM, Weinberger DR. Imaging genetics: perspectives from studies of genetically driven variation in serotonin function and corticolimbic affective processing. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;59:888–897. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlastala SA, Frank E, Kowalski J, Sherrill JT, Kupfer DJ. Stressful life events, bipolar disorder, and the “kindling model.”. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:777–786. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.4.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J, Vanderlind WM. Emotion regulation in depression: The role of biased cognition and reduced cognitive control. Clinical Psychological Science. 2014;2:402–421. [Google Scholar]

- Keeping JD, Najman JM, Morrison J, Western JS, Andersen MJ, Williams GM. A prospective longitudinal study of social, psychological and obstetric factors in pregnancy: response rates and demographic characteristics of the 8556 respondents. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 1989;96:289–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1989.tb02388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Study Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Cox BJ, Green JG, Ormel J, Zaslavsky AM. The effects of latent variables in the development of comorbidity among common mental disorders. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28:29–39. doi: 10.1002/da.20760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Eaton NR, Krueger RF, McLaughlin KA, Wall MM, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Childhood maltreatment and the structure of common psychiatric disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;200:107–115. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.093062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KJ, Conger RD, Elder GH, Jr, Lorenz FO. Reciprocal influences between stressful life events and adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems. Child Development. 2003;74:127–143. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krackow E, Rudolph KD. Life stress and the accuracy of cognitive appraisals in depressed youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:376–385. doi: 10.1080/15374410801955797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF. The structure of common mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:921–926. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. The structure and stability of common mental disorders (DSM-III-R): A longitudinal-epidemiological study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:216–227. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Chentsova-Dutton YE, Markon KE, Goldberg D, Ormel J. A cross-cultural study of the structure of comorbidity among common psychopathological syndromes in the general health care setting. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:437–447. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE. Reinterpreting comorbidity: A model-based approach to understanding and classifying psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2006;2:111–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Piasecki TM. Toward a dimensional and psychometrically-informed approach to conceptualizing psychopathology. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40:485–499. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, South SC. Externalizing disorders: Cluster 5 of the proposed meta -structure for DSM-V and ICD-11. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39:2061–2070. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laceulle OM, Vollebergh WAM, Ormel J. The structure of psychopathology in adolescence: Replication of a general psychopathology factor in the TRAILS study. Clinical Psychological Science. 2015;3:850–860. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Applegate B, Hakes JK, Zald DH, Hariri AR, Rathouz PJ. Is there a general factor of prevalent psychopathology during adulthood? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121:971–977. doi: 10.1037/a0028355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE. How things fall apart: Understanding the nature of internalizing through its relationship with impairment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:447–458. doi: 10.1037/a0019707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews A, MacLeod C. Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:167–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM. Modern approaches to conceptualizing and measuring human life stress. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:33–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Slavich GM, Georgiades K. The social environment and depression: The role of life stress (pp. 296-314) In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of Depression. 3rd Ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus version 7. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998–2014. [Google Scholar]

- Myin-Germeys I, van Os J. Stress-reactivity in psychosis: Evidence for an affective pathway to psychosis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:409–424. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Watkins ER. A heuristic for developing transdiagnostic models of psychopathology explaining multifinality and divergent trajectories. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6:589–609. doi: 10.1177/1745691611419672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofrat S, Krueger RF. How research on the meta-structure of psychopathology aids in understanding biological correlates of mood and anxiety disorders. Biology of Mood and Anxiety Disorders. 2012;2:13–17. doi: 10.1186/2045-5380-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H. Schedule for Affective Disorder and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children Epidemiologic version-5. Nova Southeastern University, Center for Psychological Studies; Ft. Lauderdale, FL: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Prenoveau JM, Zinbarg RE, Craske MG, Mineka S, Griffith JW, Epstein AM. Testing a hierarchical model of anxiety and depression in adolescents: A tri-level model. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2010;24:334–344. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine R, Venables PH, Williams M. Relationships between central and autonomic measures of arousal at age 15 years and criminality at age 24 years. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1990;47:1003–1007. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810230019003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinholt N, Krogh J. Efficacy of transdiagnostic cognitive behaviour therapy for anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis of published outcome studies. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2014;43:171–184. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2014.897367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Seeley JR, Gau JM. Key characteristics of major depressive disorder occurring in childhood, adolescence, emerging adulthood, and adulthood. Clinical Psychological Science. 2013;1:41–53. doi: 10.1177/2167702612457599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. How does stress increase risk of drug abuse and relapse? Psychopharmacology. 2001;158:343–359. doi: 10.1007/s002130100917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South SC, Krueger RF, Iacono WG. Understanding general and specific connections between psychopathology and marital distress: A model based approach. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:935–947. doi: 10.1037/a0025417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr LR, Conway CC, Hammen CL, Brennan PA. Transdiagnostic and disorder-specific models of intergenerational transmission of internalizing pathology. Psychological Medicine. 2014;44:161–172. doi: 10.1017/S003329171300055X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syngelaki EM, Fairchild G, Moore SC, Savage JC, van Goozen SH. Affective startle potentiation in juvenile offenders: the role of conduct problems and psychopathic traits. Social Neuroscience. 2013;8:112–121. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2012.712549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tackett JL, Lahey BB, Van Hulle C, Waldman I, Krueger RF, Rathouz PJ. Common genetic influences on negative emotionality and a general psychopathology factor in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:1142–1153. doi: 10.1037/a0034151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen N, Rodgers RF, Gibbs JC, Chabrol H. Callous-unemotional traits and antisocial behavior among adolescents: The role of self-serving cognitions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:229–237. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9779-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D. Rethinking the mood and anxiety disorders: A quantitative hierarchical model for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:522–536. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Beesdo-Baum K, Gloster AT, Höfler M, Klotsche J, Lieb R, Kessler RC. The structure of mental disorders re‐examined: Is it developmentally stable and robust against additions? International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2009;18:189–203. doi: 10.1002/mpr.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AG, Krueger RF, Hobbs MJ, Markon KE, Eaton NR, Slade T. The structure of psychopathology: toward an expanded quantitative empirical model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:281–294. doi: 10.1037/a0030133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon KL, Zinbarg RE. Interpreting neutral faces as threatening is a default mode for socially anxious individuals. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:680–685. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.3.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]