Abstract

Uncertainty, which is ubiquitous in decision-making, can be fractionated into known probabilities (risk) and unknown probabilities (ambiguity). Although research illustrates that individuals more often avoid decisions associated with ambiguity compared to risk, it remains unclear why ambiguity is perceived as more aversive. Here we examine the role of arousal in shaping the representation of value and subsequent choice under risky and ambiguous decisions. To investigate the relationship between arousal and decisions of uncertainty, we measure skin conductance response—a quantifiable measure reflecting sympathetic nervous system arousal—during choices to gamble under risk and ambiguity. To quantify the discrete influences of risk and ambiguity sensitivity and the subjective value of each option under consideration, we model fluctuating uncertainty, as well as the amount of money that can be gained by taking the gamble. Results reveal that while arousal tracks the subjective value of a lottery regardless of uncertainty type, arousal differentially contributes to the computation of value—i.e. choice—depending on whether the uncertainty is risky or ambiguous: enhanced arousal adaptively decreases risk-taking only when the lottery is highly risky but increases risk-taking when the probability of winning is ambiguous (even after controlling for subjective value). Together, this suggests that the role of arousal during decisions of uncertainty is modulatory and highly dependent on the context in which the decision is framed.

INTRODUCTION

In our everyday lives we regularly make choices where the outcomes are unknown. Imagine deciding whether to drive or take the bus to work, to confide in your co-worker, or to invest in a new stock. These are all decisions under uncertainty which have been fruitfully deconstructed into distinct choice parameters (Kahneman & Tversky, 1984), highlighting the critical difference between decisions made under risk—known probabilities (Bernoulli, 1738), from those made under ambiguity—unknown probabilities (Ellsberg, 1961; Knight, 1921). The fact that individuals routinely avoid outcomes associated with ambiguity is one indication that ambiguity is perceived as more aversive than risk (Becker & Brownson, 1964; Camerer & Weber, 1992; Slovic & Tversky, 1974). This has led some to argue that ambiguity is a more profound form of uncertainty compared with risk, with a stronger impact on behavior (Ellsberg, 1961). But what shapes these discrete preferences and the observable aversion to ambiguity? Based on the hypothesis that the primary function of emotion is to highlight the relevance of stimuli and events in order to guide adaptive behavior (Frijda, 2007b), here we investigate how emotion—as assessed by physiological arousal—discretely contributes to decisions of risk and ambiguity.

Despite the fact that decision-making under risk and uncertainty is one of the most active and interdisciplinary research topics in judgment and decision-making, there are many psychological constructs believed to contribute to choice which continue to elude quantification. For example, in decomposing how decisions under uncertainty are made, traditional economic models have assumed that choices are the result of a rational analysis of possible options, where value is relatively stable and—one might hypothesize—distinct from emotion (Samuelson, 1938; Von Neumann & Morgenstern, 1944). Yet simple observation of human behavior reveals clear bounds to the stability of preferences believed to accompany rationality (e.g., ambiguity aversion, gamblers’ fallacy, etc.). Because these models treat emotion as epiphenomenal, they fail to capture the potential influence of emotion on decisions of uncertainty (Loewenstein, Weber, Hsee, & Welch, 2001), which may be an important cause of the instabilities of preferences widely observed to violate traditional theories.

In the last few decades, affective scientists have established that emotion—a discrete response to external or internal events resulting in a range of reactions including subjective feelings and bodily responses (E. Phelps, 2009; K.R. Scherer, 2000)—plays a role in the representation of value. Pioneering research revealed patients with affective deficits due to damage in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex were impaired on gambling tasks (Bechara, 2004; Bechara, Damasio, & Damasio, 2000; Damasio, 1994), experimentally demonstrating that emotion—broadly construed—influences decisions of uncertainty. In these studies, participants completed the Iowa gambling task (IGT), which requires picking cards from multiple decks where each card represents a monetary reward or punishment (Bechara, Damasio, Tranel, & Damasio, 1997). Because decks vary in their payoff schedules, one must learn through trial and error which deck yields higher profits. Healthy individuals exhibit increased anticipatory skin conductance responses (SCR)1 when selecting cards from a “bad deck” compared to a more “advantageous deck,” suggesting that increased arousal signals avoidance of the bad deck to promote adaptive choice. Although this illustrates that arousal during choice can become part of the computation of value, participants are learning about reward (gain) and punishment (loss) contingencies under ambiguous contexts where there is no explicitly stated risk. Research utilizing different tasks has continued to demonstrate a quantifiable role of arousal when outcomes are uncertain (Critchley, Mathias, & Dolan, 2001; Figner, Mackinlay, Wilkening, & Weber, 2009).

However, because the unique contributions of risk and ambiguity are conflated in these tasks, it is unclear whether the arousal response steering individuals away from bad decks is associated with ambiguity or risk. Thus, the question remains: which uncertainty type is mediating the observed relationship between arousal and choice? While a recent study revealed a relationship between arousal and discrete aspects of risky decision-making, namely loss aversion (Sokol-Hessner et al., 2009), to date, research has yet to establish a relationship between arousal and risk attitudes. Accordingly, it may be that the psychological uncertainty of not knowing the probabilities of an outcome (ambiguity) evokes greater arousal than risky uncertainty. If this were the case, we would expect to see a specific role for arousal in influencing the computation of value during decisions of ambiguity but not risk. To examine the relationship between arousal and discrete parameters associated with decisions containing unknown outcomes, we measured SCR—a quantifiable measure reflecting sympathetic nervous system arousal (but not valence) (Lang, Greenwald, Bradley, & Hamm, 1993)—during choices to gamble under risky and ambiguous contexts.

METHODS

Participants

45 participants were recruited from New York University. Informed consent was obtained in a manner approved by the University Committee on Activities Involving Human Subjects. 40 participants were included in the analysis (25 females, mean age 23.6, 3.6±STD, see SI for details). Participants were paid an initial $10 and any additional monetary bonus accrued during the task (up to $125).

Task

In order to characterize the unique role of arousal in risky and ambiguous decisions, participants performed a task (Levy, Snell, Nelson, Rustichini, & Glimcher, 2010; Tymula et al., 2012) comprised of 31 gambles with known probabilities (risky trials, Fig 1A) and 31 gambles with unknown probabilities (ambiguous trials, Fig 1B). On each trial, participants had the option to choose the safe option with a sure payout of $5, or take the gamble—where each gamble had varying degrees of risk, ambiguity, and monetary value (between $5-$125). Each lottery was either risky or ambiguous, allowing us to assess an individual's sensitivity to these distinct uncertainty types. The magnitude of the potential win (money), and the probability of winning (risk and ambiguity levels) were randomly varied and matched across trial types, such that both risk and ambiguity could independently influence choice.

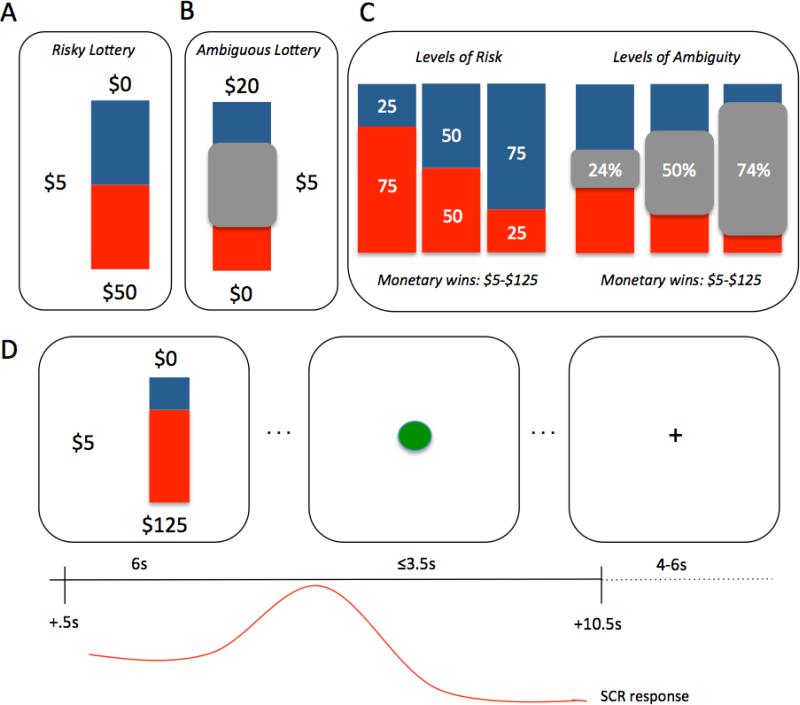

FIG 1. Experimental design.

Participants completed a computerized lottery task where each lottery depicted a stack of 100 red and blue poker chips that corresponded to actual payout bags in the testing lab. On each trial, participants could choose between receiving $5 for sure versus taking a gamble. A) An example of a risky trial that contained 50/50 odds of winning $50 (i.e. 50% risky gamble). B) An example of ambiguous trial where 50% of the chips are occluded (i.e. 50% ambiguity). In this case, the participant could gamble for $20 or take the sure $5. C) Risky trials were always presented as 25% (high risk), 50%, or 75% (low risk) probability of winning. During ambiguity trials, the probabilities were occluded to varying degrees (three levels were used) ranging from 24% to 74%. The monetary wins were always counterbalanced between red and blue chips, and were matched across risky and ambiguous trials. D) Each trial consisted of a fixed lottery presentation for 6 seconds. Once a green dot appeared the participant could key in their response to indicate playing the lottery or taking the safe bet. Skin conductance response (SCR) was recorded for 10 seconds starting .5 seconds after the lottery presentation onset.

For instance, a risky trial might juxtapose the option of $5 for sure (available on every trial) against a gamble with 50% chance of winning $50 or $0 (Fig 1A). In this example, there are 50 blue chips, 50 red chips, and the winning amount happens to be associated with the red chips. For risky trials, outcome probabilities were fully stated with varying winning probabilities of 25%, 50% and 75% (Fig 1C). On ambiguous trials, outcome probabilities were partially obscured by a gray bar with varying levels of occlusion (24%, 50%, and 74%, Fig 1C: while increasing occluder size reduces information about the contents of the “bag of chips” raising the level of ambiguity, the true objective winning probability is always 50%). To measure arousal, SCR was recorded while participants viewed the lottery and made their decision (10 second window, Fig 1D). Since raw SCRs were positively skewed, SCRs were normalized by taking the square root of each response (Dawson, Schell, & Filion, 2007). As in Levy et al., 2010, at the conclusion of the experiment, one trial was selected for realization in an entirely incentive compatible manner.

RESULTS

Gambling behavior as a function of uncertainty type

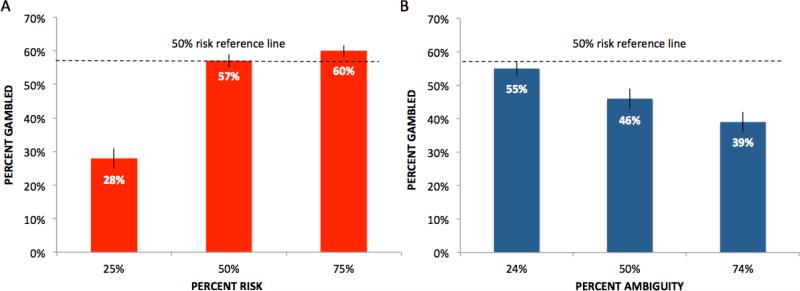

Choice behavior was initially analyzed by averaging the number of times a gamble was taken under both uncertainty types and for each level of risk and ambiguity. As expected, as the gamble became riskier and the chances of winning declined (25% risk), participants were less likely to gamble (Fig 2A). To examine whether ambiguity has an effect on behavior (Glimcher, 2008; Levy et al., 2010; Tymula et al., 2012), we explored the rates at which participants selected the gamble during ambiguous compared to purely risky lotteries. It is important to note that in this experimental design [as in (Ellsberg, 1961)], even though the increasing occluder size reduces information about the outcome odds, the objective-winning probability is always 50%. Confirming that ambiguous uncertainty is more aversive than risk (Slovic & Tversky, 1974), all ambiguous trials were treated as if the winning probability was less than 50%, with participants taking even fewer gambles as the ambiguity level increased (Fig 2B).

FIG 2. Behavioral Results.

A) Participants gambled the most when the trial contained known probabilities (risk) and there was a high probability of winning (75% chance of winning). As the lottery becomes riskier (25% chance of winning) participants are less likely to gamble, reducing their gambling rates to 28%. B) Ambiguous uncertainty is perceived as more aversive than risky uncertainty: trials that contained highly ambiguous trials (i.e. 50% and 74% ambiguity) were treated as if the winning probability was less than 50%. Gambling rates at 50% risk is indicated by the dotted reference line.

Emotional arousal and subjective value

To explore the relationship between arousal and the subjective value (SV) of a given lottery, we modeled the SV for each gamble under consideration as a function of the fluctuating amount of risk and ambiguity across trials, and the amount of money that could be gained. Although there are a number of models that account for decisions under ambiguity, Gilboa and Schmeidler's maxmin utility model provides a simple and widely used model anchoring parameters for best and worst case scenarios (Gilboa & Schmeidler, 1989), where one parameter indicates risk sensitivity (α) and the second parameter indicates ambiguity sensitivity (β). This ‘utility function’ takes into account the effect of ambiguity on perceived winning probability as:

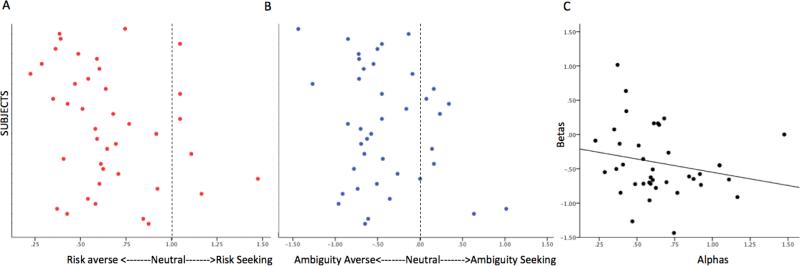

where for each trial, SV is calculated as a function of the lottery's objective winning probability (p), level of ambiguity (A), and monetary value (v), accounting for each individual's risk (α) and ambiguity (β) attitudes which are obtained from the behavioral fit of the model. Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of participants’ risk and ambiguity attitudes revealing these attitudes are not correlated (Pearson's two tailed correlation r=−.22, p=.19, R2 =.045). Classically used by Luce (1959), as well as by Holt and Laury (2002), these attitudes are derived by fitting choice data using the maximum likelihood with the following probabilistic choice function,

where SVF and SVV are the subjective values of the fixed and variable options, respectively, and γ is the slope of the logistic function, which is a participant specific parameter (see SI for model fits and percentage of choices correctly predicted by model [Table S5], as well as other possible models that could account for behavior [Table S6]). This utility function captures the relative value a participant places on ambiguous versus risky lotteries, allowing us to decompose the subjective value of each lottery and explore its discrete relationship with the arousal response.

FIG 3. Risk and Ambiguity Parameters.

A) Participants’ risk attitudes (alphas, α) and B) ambiguity attitudes (betas, β) as derived from the model; see Table S5 for full descriptive statistics of model parameters. An α>1 indicates a person is risk-seeking and more likely to gamble on risky trials, while an α<1 indicates a person is risk averse and less likely to gamble on risky trials (α=1 indicates risk neutral). A β>0 indicates a person is ambiguity averse and less likely to gamble on ambiguous trials, while a β<0 indicates a person is ambiguity seeking and likely to gamble during ambiguous lotteries. For illustration purposes, betas have been inverted to align on the same scale (aversion seeking) as risk attitudes. C) We found no relationship at the population level between risk and ambiguity attitudes (p>.1), replicating previous work (Levy et al., 2010).

To examine this relationship between SV and physiological arousal (SCR), we ran a trial-by-trial hierarchal linear regression (we report maximal models for all analyses [Barr, et al., 2013]) modeling arousal as a function of every trial's SV given a participant's risk and ambiguity attitudes obtained from the model. This captures the relationship between arousal and SV, irrespective of uncertainty type (Table 1). Results reveal a main effect of SV, indicating greater subjective value predicts greater arousal. Independent regressions were run for each uncertainty type, revealing that under both risk and ambiguity, greater SV similarly predicts increased arousal (post estimation tests reveal risk and ambiguity coefficients are not significant from another, P>.1).

TABLE 1. SCRi,t = β0 + β1 Subjective Valuei,t.

SCR ~ Subjective Value; where SV is indexed by subject and trial. Independent regressions are also reported for risk and ambiguity trials.

| Dependent Variable | Coefficient (β) | Estimate (SE) | t-value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All SCR | Intercept | 0.47 (.06) | 7.28 | <0.001*** |

| All SV | 0.0009 (.19) | 2.84 | 0.004** | |

| Risk SCR | Intercept | 0.47 (.07) | 7.15 | <0.001*** |

| Risk SV | 0.0006 (.0003) | 2.00 | 0.04* | |

| Ambiguity SCR | Intercept | 0.48 (.07) | 7.36 | <0.001*** |

| Ambiguity SV | 0.002 (.001) | 1.80 | 0.067+ |

p<0.001

p<0.01

p<0.05

Emotional arousal and choice

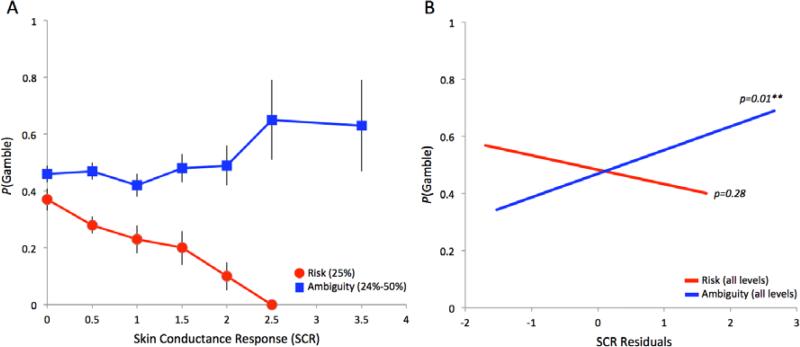

Given this positive relationship between subjectively valuing a lottery and the arousal response—and that subjective value robustly (and unsurprisingly) predicts taking the gamble in both risky and ambiguous contexts (Tables S4, Fig S2)—we further hypothesized there should also be a relationship between choosing to gamble and arousal level. To explore this, we first tested whether higher arousal predicts gambles during risky and ambiguous lotteries. While we observed no overall relationship between arousal and gambling, results revealed discrete and divergent relationships between arousal and gambling depending on whether the trial was risky or ambiguous (Table 2). Under risk, enhanced arousal predicted taking the safe option, and this was solely attributed to high-risk trials where there was only a small chance of winning (Fig 4A, Table 2A). In other words, while no relationship between arousal and choice during gambles with medium to low levels of risk was observed, for gambles with low odds of winning, higher arousal predicted less gambling.

TABLE 2. Choicei,t = β0 + β1 SCRi,t β2 Uncertainty typei,t.

Choice ~ SCR Uncertainty Type; where SCR is indexed by subject and trial, and uncertainty type is an indicator variable for risk (0) and ambiguity (1); choice coded as safe (0) and gamble (1).

| Dependent Variable | Coefficient (β) | Estimate (SE) | t-value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choice | Intercept | 0.03 (.13) | 0.35 | 0.72 |

| SCR | −0.22 (.13) | −1.68 | 0.09 | |

| Uncertainty Type | −0.29 (.13) | −2.22 | 0.02* | |

| SCR Uncertainty Type | 0.45 (.16) | −2.90 | 0.004** |

***p<0.001

p<0.01

p<0.05

FIG 4.

A) Higher arousal predicts attenuated gambling during highly risky trials with low odds of winning the lottery (25%). In contrast, higher arousal during low (25%) and medium (50%) levels of ambiguous uncertainty (levels collapsed) resulted in increased gambling. B) Relationship between arousal and choice, controlling for subjective value of a lottery, indicates that arousal predicts greater gambling behavior under ambiguous conditions but has no predictive power during risky conditions.

TABLE 2A. Choicei,t = β0 + β1SCRi,t (Risk25%i,t) + β2SCRi,t (Risk50%i,t) + β3SCRi,t (Risk75%i,t).

SCR ~ SCR Risk Level; where SCR and Risk level is indexed by subject and trial and each level of Risk level is an indicator variable.

| Dependent Variable | Coefficient (β) | Estimate (SE) | t-value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choice | Intercept | 0.10 (.09) | 1.11 | 0.26 |

| SCR Risk 25% | −2.06 (.32) | −6.37 | <0.001*** | |

| SCR Risk 50% | 0.14 (.16) | 0.87 | 0.38 | |

| SCR Risk 75% | 0.25 (.16) | 0.10 | 0.10 |

p<0.001

**p<0.01

*p<0.05

In contrast, during ambiguous trials, enhanced arousal predicted the likelihood that an individual would take the gamble (Fig 4B, Table 2B), indicating when the probability of the outcome is unknown, heightened arousal increases gambling rates. Reaction time tests exploring whether this effect could be explained by ambiguous choices being more cognitively demanding revealed no such evidence (see supplement). To further unpack why increased arousal amplifies willingness to gamble during ambiguity but not risk, we investigated the relationship between all three variables of interest: subjective value, choice, and arousal.

TABLE 2B. Choicei,t = β0 + β1SCRi,t (Amb25%i,t) + β2SCRi,t (Amb50%i,t) + β3SCRi,t (Amb75%i,t).

SCR ~ SCR Ambiguity Level; where SCR and Ambiguity level is indexed by subject and trial and each level of Ambiguity is an indicator variable.

| Dependent Variable | Coefficient (β) | Estimate (SE) | t-value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choice | Intercept | −0.27 (.13) | −2.08 | 0.03* |

| SCR Ambiguity 25% | 0.54 (.17) | 3.09 | 0.002** | |

| SCR Ambiguity 50% | 0.32 (.16) | 1.90 | 0.05* | |

| SCR Ambiguity 75% | −0.08 (.17) | −0.45 | 0.64 |

***p<0.001

p<0.01

p<0.05

Emotional arousal, subjective value and choice

To further isolate the role of arousal in guiding choices to gamble as a function of risk and ambiguity, we used residuals from the regression (SV ~SCR [Table 1]) to predict the probability of taking the gamble, which controls for the subjective value of each lottery. This enables us to test the direct influence of arousal on gambling, irrespective of the effects of subjective value. Results reveal increased arousal only predicts gambling when the probabilities are unknown (Table 3, Fig 4B), with no discernable relationship between arousal and choice under risk. See supplement for multi-level mediation analysis confirming this relationship.

Table 3.

Choicei,t = β0 + β1SCRresidualsi,t β2Uncertainty typei,tChoice ~ SCR residuals Uncertainty Type; where the SCR residuals are taken from the independent risk and ambiguity regressions reported in Table 1 (indexed by subject and trial). Uncertainty type is an indicator variable for risk (0) and ambiguity (1). Regressions are also run separately for risk and ambiguity.

| Dependent Variable | Coefficient (β) | Estimate (SE) | t-value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Choice | Intercept | −0.10 (.08) | −1.27 | 0.20 |

| SCRresid Uncertainty Type | 0.35 (.15) | 2.40 | 0.016* | |

| Risk Choice | Intercept | −0.07 (.08) | −.93 | 0.35 |

| Risk SCRresid | −0.21 (.19) | −1.08 | 0.28 | |

| Ambiguity Choice | Intercept | −0.14 (.11) | −1.3 | 0.19 |

| Ambiguity SCRresid | 0.36 (.15) | 2.4 | 0.01* |

***p<0.001

**p<0.01

p<0.05

DISCUSSION

Although both risk and ambiguity are ubiquitous in decision-making, until now, differentiating the specific role of arousal's role during different types of uncertainty has not been demonstrated. Here we find diverging functional roles for arousal and its contribution to the computation of value depending on whether the decision contains purely risky uncertainty, or both risky and ambiguous uncertainty. First, individuals gamble more on risky trials than ambiguous trials, confirming that ambiguity is more aversive than risk. Second, irrespective of uncertainty type, arousal tracks the subjective value of the lottery. Third, arousal plays a specific role in influencing decisions under risk: higher arousal is tightly coupled with choosing the safe option, such that gambling decreases, but only when the risk is high and there is little chance of winning. That arousal does not seem to broadly contribute to the representation of value during risky uncertainty suggests a more limited role for arousal in the valuation of risk. In contrast, when uncertainty has a qualitatively different nature and the probability of winning is unknown, enhanced arousal plays a broad role in increasing gambling. Even after controlling for the subjective value of the lottery, this high arousal/increased gambling relationship during ambiguous uncertainty persists. Dovetailing with previous research (E. A. Phelps, Lempert, & Sokol-Hessner, 2014), this suggests that arousal should not be treated as a unitary construct in risky decision-making. Rather, arousal makes divergent contributions towards the representation of value when the decision space contains known or unknown uncertainty.

SCRs are an objective sign of psychological and physiological arousal (Pribram & Mcguinness, 1975) which are known to correlate with a myriad of environmental stimuli, including novelty, pleasantness, unpleasantness, and value (Frijda, 2007a; Otto, Knox, Markman, & Love, 2014; K. R. Scherer, 1984; K. R. Scherer & Peper, 2001). Given this, SCR is assumed to be a multicomponent non-valenced signal that is highly adaptive, primed to detect stimuli that are critical for the survival and wellbeing of the organism (Frijda, 2007b; Ohman, 1986). Thus, it is not surprising that we found arousal indexes more than one aspect of the decision space. Previously, however, the relationship between arousal and choice has been described almost exclusively within the context of risk, and was presumed to have a linear relationship in predicting attenuated gambling (Bechara, 2004; Bechara et al., 1997). Yet in prior research (i.e. the IGT), risk and ambiguity, as well as the potential for both monetary losses and gains, are all covariates, making it difficult to determine the specific role of arousal in guiding choice. In our task, the only difference between deciding on a risky versus an ambiguous outcome is the amount of perceived uncertainty—all other components of the task are held constant. In contrast to previous work, once these aspects of the decision space are controlled for, we observe a limited role for arousal in guiding risky choices: heightened arousal predicts attenuated gambling only when one knows the chance of winning is very low. The opposite relationship is observed when the outcomes of winning are unknown: increased arousal predicts increased gambling during ambiguous uncertainty.

Our finding that increasing arousal correlates with the subjective value of the lottery— irrespective of context—illustrates that arousal is highly responsive to value (Frijda, 2007b; Zink, Pagnoni, Martin-Skurski, Chappelow, & Berns, 2004). This aligns with research demonstrating that heightened arousal facilitates detection of potentially important environmental events and information; in this case lotteries that bear higher subjective values are more likely to reap higher payouts. However, since the role of value is to provide a metric for the decision maker in weighing various options for choice, the subjective value of the lottery should determine whether an individual decides to take the gamble, irrespective of whether the context is risky or ambiguous2. Interestingly though, once subjective value (an SCR-free model-based estimate of choice propensity) is controlled for, we found arousal predicts greater gambling only during ambiguity, but not risk.

Why might arousal motivate gambling only when there is great uncertainty about the probability of winning? During conditions of ambiguous uncertainty, an individual must make more inferences about the state of the decision space in order to predict possible outcomes. When there is explicit information about outcome probabilities—as there is in risk—individuals can make better-informed decisions to optimize their payouts. For example, knowing there is a 75% chance of winning $125 indicates that the odds are in one's favor to win a large payout. However, when the uncertainty of winning is ambiguous and there is little knowledge of whether one's choice will reap the desired outcome, individuals must effectively guess which option will lead to the best outcome. In these noisy environments, teasing apart the value of the possible outcomes becomes more difficult, and thus the body reacts with an amplified arousal response. Simply put, unlike during highly risky situations where enhanced arousal plays a clear and specific role in signaling adaptive choice, ambiguous uncertainty poses an obstacle for effective decision-making—as there is a perception of inadequate knowledge about possible outcomes. Simply put, arousal appears to play a clear adaptive role when there is sufficient knowledge about the outcomes, but when there is insufficient knowledge, arousal enhances the value representation of the possible outcome, which is either adaptive or maladaptive depending on the parameters of the decision space.

Here we illustrate that arousal contributes to the calculation of value during choice in a way not captured by the traditional arousal-free models. However, arousal's role is modulatory in nature (E. A. Phelps et al., 2014), varying depending on the context in which the decision is framed. Under risky and ambiguous contexts, arousal has divergent effects in shaping our perceptions of uncertainty. Questions remain: if arousal differentially guides choices depending on the type of uncertainty, then pharmacologically blunting arousal responses (Sokol-Hessner et al., 2015), or employing emotion regulation techniques to regulate the arousal response (Sokol-Hessner et al., 2009) could result in divergent behavior, enhancing highly risky choices and possibly diminishing ambiguous choices. Future work can help further tease apart how emotional arousal contributes to the representation of value during decision-making.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Michael Grubb and Ross Otto for their valuable discussions and comments when designing the experiment and running analysis. Financial support from the National Institute of Aging is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Author note

This work was previously presented at the 2015 Society for Neuroeconomics Annual Conference.

Historically, the terms SCR and a rousal are used interchangeably to describe emotion. There is robust research mapping the relationship between autonomic sympathetic activity and arousal. However, the arousal response indexes multiple aspects of emotion and has been linked to fear, anger, and happiness, depending on the context, as well as other cognitive processes such as cognitive load. Here we refer to SCR as arousal, but see (Boucsein, 1992; Lempert & Phelps, 2014; Power & Dalgleish, 2008) for a comprehensive discussion of arousal's role in measuring emotion.

Indeed, the fact that we derive subjective value by analyzing choice makes this almost tautologically true.

REFERENCES

- Barr DJ, Levy R, Scheepers C, Tily HJ. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory and Language. 2013;68(3) doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A. The role of emotion in decision-making: evidence from neurological patients with orbitofrontal damage. Brain and cognition. 2004;55(1):30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2003.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio H, Damasio AR. Emotion, decision making and the orbitofrontal cortex. Cerebral cortex. 2000;10(3):295–307. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, Damasio AR. Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science. 1997;275(5304):1293–1295. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SW, Brownson FO. What Price Ambiguity - or the Role of Ambiguity in Decision-Making. Journal of Political Economy. 1964;72(1):62–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bernoulli D. Exposition of a New Theory on the Measurement of Risk. Econometrica. 1738;22(1):23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Boucsein W. Electrodermal Actitivty. Plenum Press; NY, NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Camerer C, Weber M. Recent Developments in Modeling Preferences - Uncertainty and Ambiguity. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 1992;5(4):325–370. [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HD, Mathias CJ, Dolan RJ. Neural activity in the human brain relating to uncertainty and arousal during anticipation. Neuron. 2001;29(2) doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasio A. Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. Reprint edition 2005 ed. Penguin Books; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson ME, Schell A, Filion D. The Electrodermal System. In: T. L. Cacioppo JT, Berntson GG, editors. Handbook of psychophysiology. Cambridge University Press; 2007. pp. 159–181. [Google Scholar]

- Ellsberg D. Risk, Ambiguity, and the Savage Axioms. Econometrica. 1961;29(3):454–455. [Google Scholar]

- FeldmanHall O, Mobbs D, Evans D, Hiscox L, Navardy L, Dalgleish T. What we say and what we do: The relationship between real and hypothetical moral choices. Cognition. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figner B, Mackinlay RJ, Wilkening F, Weber EU. Affective and Deliberative Processes in Risky Choice: Age Differences in Risk Taking in the Columbia Card Task. Journal of Experimental Psychology-Learning Memory and Cognition. 2009;35(3):709–730. doi: 10.1037/a0014983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frijda NH. Klaus Scherer's article on “What are emotions?” - Comments. Social Science Information Sur Les Sciences Sociales. 2007a;46(3):381–383. [Google Scholar]

- Frijda NH. The Laws of Emotion. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2007b. [Google Scholar]

- Gilboa I, Schmeidler D. Maxmin Expected Utility with Non-Unique Prior. Journal of Mathematical Economics. 1989;18(2):141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Glimcher PW. Understanding risk: A guide for the perplexed. Cognitive Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2008;8(4):348–354. doi: 10.3758/CABN.8.4.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CA, Laury SK. Risk aversion and incentive effects. American Economic Review. 2002;92(5):1644–1655. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Tversky A. Choices, values, and frames. American Psychologist. 1984;39(4):341. [Google Scholar]

- Knight FH. Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit. Houghton Mifflin Company; Boston: 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Greenwald MK, Bradley MM, Hamm AO. Looking at Pictures - Affective, Facial, Visceral, and Behavioral Reactions. Psychophysiology. 1993;30(3):261–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1993.tb03352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lempert KM, Phelps EA. Neuroeconomics of Emotion and Decision-Making. In: Glimcher PW, Ernst F, editors. Neuroeconomics. 2nd Edition ed. Academic Press; London, UK: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Levy I, Snell J, Nelson AJ, Rustichini A, Glimcher PW. Neural Representation of Subjective Value Under Risk and Ambiguity. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2010;103(2):1036–1047. doi: 10.1152/jn.00853.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein GF, Weber EU, Hsee CK, Welch N. Risk as feelings. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127(2):267–286. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luce RD. Individual Choice Behavior: A theoretical analysis. Wiley; New York: 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Ohman A. Face the Beast and Fear the Face - Animal and Social Fears as Prototypes for Evolutionary Analyses of Emotion. Psychophysiology. 1986;23(2):123–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1986.tb00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto AR, Knox WB, Markman AB, Love BC. Physiological and behavioral signatures of reflective exploratory choice. Cognitive Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2014;14(4):1167–1183. doi: 10.3758/s13415-014-0260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps E. The Study of Emotion in Neuroeconomics. In: Glimcher PW, Camerer C, Fehr E, Poldrack RA, editors. Academic Press; Neuroeconomics: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps EA, Lempert KM, Sokol-Hessner P. Emotion and Decision Making: Multiple Modulatory Neural Circuits. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2014;37:263–287. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071013-014119. Vol 37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power M, Dalgleish T. Cognition & Emotion, From Order to Disorder. 2nd Edition ed. Psychology Press; NY, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pribram KH, Mcguinness D. Arousal, Activation, and Effort in Control of Attention. Psychological Review. 1975;82(2):116–149. doi: 10.1037/h0076780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson PA. A Note on the Pure Theory of Consumer's Behaviour. Economica-New Series. 1938;5(17):61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer KR. Emotions - Functions and Components. Cahiers De Psychologie Cognitive-Current Psychology of Cognition. 1984;4(1):9–39. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer KR. Psychological models of emotion. In: Borod J, editor. The Neuropsychology of Emotion. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2000. pp. 137–162. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer KR, Peper M. Psychological theories of emotion and neuropsychological research. In: Grafman FBJ, editor. Handbook of Neuropsychology. Vol. 5. 2001. pp. 17–48. [Google Scholar]

- Slovic P, Tversky A. Who Accepts Savages Axiom. Behavioral Science. 1974;19(6):368–373. [Google Scholar]

- Sokol-Hessner P, Hsu M, Curley NG, Delgado MR, Camerer CF, Phelps EA. Thinking like a trader selectively reduces individuals' loss aversion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(13):5035–5040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806761106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol-Hessner P, Lackovic SF, Tobe RH, Camerer CF, Leventhal BL, Phelps EA. Determinants of Propranolol's Selective Effect on Loss Aversion. Psychol Sci. 2015;26(7):1123–1130. doi: 10.1177/0956797615582026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tymula A, Belmaker LAR, Roy AK, Ruderman L, Manson K, Glimcher PW, et al. Adolescents' risk-taking behavior is driven by tolerance to ambiguity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(42):17135–17140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207144109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Neumann J, Morgenstern O. Theory of games and economic behavior. Princeton university press; Princeton: 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Zink CF, Pagnoni G, Martin-Skurski ME, Chappelow JC, Berns GS. Human striatal responses to monetary reward depend on saliency. Neuron. 2004;42(3):509–517. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.