Abstract

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) affects up to 10% of pregnancies and often results in short- and long- term sequelae for offspring. The mechanisms underlying IUGR are poorly understood, but it is known that healthy placentation is essential for nutrient provision to fuel fetal growth, and is regulated by immunologic inputs. We hypothesized that in pregnancy, maternal food restriction (FR) resulting in IUGR would decrease the overall immunotolerant milieu in the placenta, leading to increased cellular stress and death. Our specific objectives were to evaluate: (1) key cytokines (e.g. IL10) that regulate maternal-fetal tolerance, (2) cellular processes (autophagy and ER stress) that are immunologically-mediated and important for cellular survival and functioning, and (3) evaluate the resulting IUGR phenotype and placental histopathology. After subjecting pregnant mice to mild and moderate FR from gestational day (GD) 10 to 19, we collected placentas and embryos at GD19. We examined RNA sequencing data to identify immunologic pathways affected in IUGR-associated placentas and validated mRNA expression changes of genes important in cellular integrity. We also evaluated histopathologic changes in vascular and trophoblastic structures as well as protein expression changes in autophagy, ER stress, and apoptosis in the mouse placentas. Several differentially expressed genes were identified in FR compared to control mice, including a considerable subset that regulates immune tolerance, inflammation and cellular integrity. In summary, maternal food restriction decreases anti-inflammatory effect of IL10 and suppresses placental autophagic and ER stress responses, despite evidence of dysregulated vascular and trophoblast structures leading to IUGR.

Keywords: mouse placenta, vasculature, intrauterine growth restriction, autophagy, ER stress, Interleukin-10

1. Introduction

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is a poorly understood complication of pregnancy, affecting up to 10% of pregnancies. As the causes of IUGR are myriad, IUGR is thought to encompass a broad spectrum of diseases that results from poor nutrient provision to the fetus. This adverse intrauterine environment may, in some cases, result from disordered placentation or poor maternal health and nutrition [1,2]. It is critical to understand the contribution of maternal diet towards the pathophysiology of IUGR, as IUGR not only places offspring of these pregnancies at increased risk of short-term morbidity, but also at increased risk for adult-onset cardiovascular and metabolic diseases [3-6].

The placenta plays an important role in IUGR as it is the essential organ for transportation of nutrients from maternal blood to the fetus. Studies of placental gene expression have shown that the placenta is able to sense and respond to changes in the immediate environment (e.g. maternal diet) in ways that directly alter the transport of nutrients to the fetus [7-9]. The transfer of nutrients is largely mediated by blood flow and transcellular transport, via placental vasculature and across trophoblast cells. The reported placental changes seen in human IUGR include a degenerated syncytiotrophoblastic lining, fibrin deposition, hypovascular/avascular villi and large areas of infarction [10]. These findings likely represent changes that occur in response to longstanding nutrient and oxygen insufficiency in IUGR. These changes further exacerbate poor blood flow to the fetus, resulting in poor in-utero growth of the fetus.

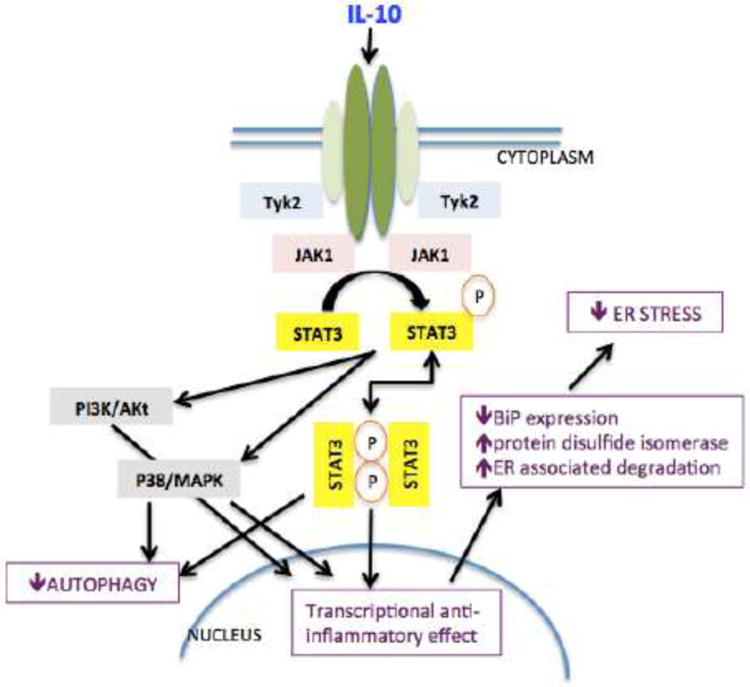

The development and maintenance of placental structure and cellular function are dependent upon immune modulation with several pathways communicating to allow immune tolerance at the maternal-fetal interface. A growing body of evidence suggests that pathology in pregnancy disorders such as preeclampsia, recurrent miscarriage and IUGR can be related to altered immune tolerance. Interleukin-10 (IL10), an anti-inflammatory cytokine, is a key immunologic signal that is altered in these pregnancy states. It normally acts as an anti-inflammatory pleiotropic regulator in pregnancy via suppression of inflammatory cytokines, inhibition of antigen expression via major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II expression, protection against vascular dysfunction and inflammation, and modulation of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and autophagy [11] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scheme representing crosstalk between IL10, autophagy, ER stress, and apoptotic pathways.

Our specific research objectives were to ascertain the effect of maternal food restriction resulting in placental insufficiency and IUGR on key cytokines in pregnancy affecting immune tolerance, e.g. IL10, and on downstream immunologic pathways regulating cellular maintenance, e.g. autophagy and ER stress. As autophagy and ER stress are processes that are essential for cellular functioning in the face of pathologic stimuli such as nutrient deprivation and hypoxia, we hypothesized that maternal food restriction during pregnancy would result in IUGR and concomitantly decrease “anti-inflammatory” signaling in the placenta and increase cellular stress and death via alterations in autophagy and ER stress. To do this, we exposed pregnant mice to varying degrees (25% and 50% restriction of daily food intake, by weight) of maternal food restriction (FR) during the second half of gestation, and assessed the effect of maternal FR on placenta and embryo weight. FR during gestational days (GD) 10-19 was chosen to mimic the chronicity of human IUGR, which more commonly manifests in the second half of pregnancy. This time period was also chosen because placental function and gene expression dramatically affect fetal growth patterns during this portion of pregnancy. To initially undertake a global approach, we analyzed RNA sequencing data generated from whole placental samples to identify key genes involved in immunomodulatory pathways that were affected in our animal model of IUGR. We identified candidate genes not previously characterized in placental pathology per se, but known to be important in autophagy, ER stress, and vascular inflammation in other human diseases. We then validated altered mRNA expression of these specific genes by real time PCR. We employed a combination of western immunoblotting as well as immunohistochemistry to evaluate whether tissue-level and/or protein expression of IL10 and markers of autophagy and ER stress pathways reflected the same directional changes as seen in the transcriptomic changes in these placentas. We also examined the placentas for histopathologic findings consistent with IUGR, and to localize associated degenerative changes that we would expect to see with altered autophagy and ER stress pathways. Taken together, these experiments further our understanding of how maternal diet specifically affects the immunologic milieu at the maternal-fetal interface and the cellular health of key placental structures for nutrient provision to the fetus.

2. Methods and materials

This study was conducted in accordance with established guidelines and all protocols [12] were approved by the Animal Research Committee of the University of California Los Angeles in accordance with the guidelines set by the National Institutes of Health. C57/BL6 mice were housed in 12:12 hour light-dark cycles with ad libitum access to a standard rodent chow diet (Pico Lab Rodent Diet 20, cat# 5053, Lab Diet, St. Louis, MO; major ingredients included: ground corn, soybean meal, wheat middlings, whole wheat, fish meal, dried beet pulp, wheat germ, cane molasses, brewers dried yeast, ground oats, dehydrated alfalfa meal, soybean oil, whey, and calcium carbonate), and the vitamin and mineral premixes. The macronutrient content of the diet was comprised of the following: carbohydrate (62.3% energy), protein (24.5% energy), and fat (13.1 % energy).

2.1. Placental samples

At 8 weeks of age, male and female mice were mated overnight, and pregnant mice were identified by the presence of a vaginal plug (designed as gestational day 1). Pregnant females were transferred to individual cages and reared on the same chow diet ad libitum until gestational day 10, at which point they were randomly assigned to three groups: 1) control group - ad libitum access to the standard rodent diet, 2) mild restriction group – restricted by 25% of their daily intake from gestational day 10 to 19, and 3) moderate restriction group – restricted by 50% of their daily intake from gestational day 10 to 19, as previously described (n=4-5 pregnant mothers/group) [7]. On GD 19, animals were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of 100 mg/kg of phenobarbital. The placentas were separated from the respective fetuses and collected (n=20-25/group). The placentas and fetuses were weighed in a Mettler AB104 precision balance (0.01 mg sensitivity), and then immediately snap-frozen and stored at -80°C until further analysis. In some cases, placentas were fixed in paraffin and then processed for immunohistochemical staining, as described below (section 2.6).

2.2. RNA sequencing

For this analysis, only two groups were considered. Whole placental samples were obtained from control and 50% FR groups (n=5/group). Briefly, tissue from single placentas was homogenized and RNA extracted as previously described [7]. Total RNA was quantified using the Qubit RNA assay (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). 1,000ng of total RNA was used as starting material for each sample. Library preparation was performed using the Illumina TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation kit, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Libraries were run using 50-bp single-end reads on the HiSeq2000 System (Illumina), and reads were mapped with TopHat, which keeps unique alignments and those with up to two mismatches [13]. The quality of alignments was checked with FastQC and the resulting file was processed through the HTSeq program to create a gene matrix as input for downstream analysis. DESeq [14] was used to calculate differential expression, generating Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads (RPKM) per gene [7].

2.3. Library analysis

Genes were considered differentially expressed between control and the 50% FR group if differentially methylated regions (DMR) located close to those genes had significantly different mean expression levels as determined by Student's t-test, p<0.05. Details on determination of mean methylation levels are included in section 2.3.1 below. Pathway analysis was then conducted to identify genes that were involved in functional immunomodulatory pathways. Specifically, genes previously identified as important in inflammatory, immunologic, vascular, autophagy, or ER stress pathways in human disease were selected for further validation.

2.3.1. Statistical analysis methods used in RNA sequencing and library analysis

For each CG site, a t-score was calculated from the t-test of mean difference between the two groups of comparison. Sites with an absolute t-score greater than or equal to 1.5 (approximately top 10%) were deemed candidate DMRs. For each candidate DMR, z-score of average t-score from all CG sites within the region was calculated. If the absolute z-score was greater than threshold, as calculated based upon the false discovery rate of <5% [7], and mean methylation levels in the two groups differed by at least 15%, the region was considered a DMR. Genes that overlapped or had transcription start sites within 5Kbp of the DMR were considered associated genes to the DMR of interest. Genes were considered differentially expressed between control and the 50% FR group if differentially methylated regions (DMR) associated with those genes had mean expression levels that were significantly different between the two groups, by Student's t-test, with unadjusted p-value<0.05. Log2 ratios and adjusted p-values using Bonferroni correction were also calculated. False discovery rate for p value cutoffs was <5% [7].

2.4. qRT-PCR

Total cellular RNA was isolated using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA. USA). cDNA was generated from 1 μg of total RNA from placental tissue (n=6/group) by reverse transcription (RT) using a Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). Amplification was performed in triplicate using Taqman-based detection on a Step One real-time quantitative PCR thermocycler (Applied Biosystems), as previously described [12]. For IL-10, the IL-10 Taqman Gene expression Assay Mm01288386_m1 was used according to the manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems). For all other genes of interest, a Fam/Tamra probe was used (Eurofins, MWG Operon). Relative gene expression was calculated using the comparative CT method [15] with 18S (Applied Biosystems, #4319413E) expression used as the internal control for normalization. The amplification cycles consisted of: 50°C for 2 minutes, 95°C for 20 seconds, then 45 cycles of 95°C for 1 second (denaturation) and 56-59°C for 20 seconds (annealing), followed by 72°C for 5 minutes (extension). Specific annealing temperatures, exon-spanning primers for amplification, and probe sequences for detection are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Primer and probe sequences and conditions used for qRT-PCR.

| Gene | Annealing temperature | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Probe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dram1 | 57°C | 5′-ACACAGGAACAAC TCCTCCA | 5′-AACGGGAGTGCT GAAGTAGC | 5′-TCTCTGCATTTCT TGGCGCAGC |

| Fbxo32 | 57°C | 5′-TTCTCAGAGAGGCA GATTCG | 5′-GAGAATGTGGCA GTGTTTGC | 5′-CCAATCCAGCTGC CCTTTGTCA |

| Scd1 | 59°C | 5′-TTCTTCTCTCACGT GGGTTG | 5′-CGGGCTTGTAGTA CCTCCTC | 5′-CGCAAACACCCG GCTGTCAA |

| Pdia4 | 57°C | 5′-GGATGCTGCTAACA ACCTGA | 5′-CCAGGGAGACTTT CAGGAAC | 5′-CAAGTTTCACCAC ACTTTCAGCCCTG |

| Creld2 | 57°C | 5′-TGTGTGGATGTGGA TGAGTG | 5′-AGCCGTTGACATT CTCACAG | 5′-CATCTCCGTGCAG CGATGGC |

| Derl3 | 57°C | 5′-CTCTTCGTGTTCCG CTACTG | 5′-AGGAATCCCAGC AGAGTCAT | 5′-AACCCTCCTCCAG CATGCGG |

| Map3k6 | 56°C | 5′-TACAACGCGGATGT AGTGGT | 5′-AACAGAGGAGCA CGTTGTTG | 5′-TTCTACCACCTCG GCGTGCG |

| C1qa | 57°C | 5′-GAGCATCCAGTTTG ATCGG | 5′-CATCCCTGAGAG GTCTCCAT | 5′-ACCACGGAGGCA GGGACACC |

2.5. Western blotting

BAX (Bcl-2 associated X protein) and BCL2 (B-cell lymphoma 2) protein detection was undertaken to evaluate for changes in apoptosis in whole placental samples. BIP (Binding immunoglobulin protein) detection was undertaken by Western blot analysis to evaluate overall ER stress in whole placental samples. Briefly, tissue homogenates from whole placental samples were solubilized in 50mM Tris, pH 6.8, containing 2% SDS. Protein concentration was determined by using the Bio-Rad dye-binding assay. Western blotting was performed as described previously (n=9/group) [16]. Briefly, the solubilized protein homogenates (20 μg) were subjected to electrophoresis on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Transblot; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The following primary antibodies were used for signal detection: BAX antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, 1:750 dilution), BCL2 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, 1:750 dilution), and BIP antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000 dilution). Anti-vinculin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, 1:7000) was used to detect endogenous vinculin, which served as an internal control for inter-lane loading variability [17]. For all bands, resultant optical density was ensured as linear to the loading protein concentrations, and the intensity of the protein bands was assessed by densitometry using the Scion Image software program [16].

2.6. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry for detection of IL10, markers of autophagy (LC3B, a ubiquitin-like protein involved in the ATG-8-conjugation system, necessary for the formation of the autophagosome), vasculature (CD34+ endothelial cells), and trophoblast cells (cytokeratin staining) was performed. All tissues were rinsed in PBS, fixed in cold 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hours and then transferred to cold 70% ethanol. Samples were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 5 μm thickness. A single section from each placenta was stained with hematoxylin and eosin by the Tissue Procurement Core Laboratory (TPCL) at UCLA. Samples were deparaffinized and dehydrated in alcohol. Antigen retrieval was performed using 0.1 M citrate, pH 6.0, at 95°C for 20 min. The slides were then incubated with antibody or control rabbit pre-immune serum at the same dilution overnight. The antibody signal was visualized using the Vectastain ABC kit (Vector, PK6101). Negative controls (no incubation with primary antibody) were included for each experiment. Anti-IL10 (Abcam, ab33471) was used at a dilution of 1:100; anti-CD34 (Abcam, ab81289) was used at a dilution of 1:100; pan cytokeratin (DAKO, Z0622) was used at a dilution of 1:50; LC3B (Abcam, ab168831) was used at a dilution of 1:50. Antibody staining was detected using the appropriate species Vector ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, PK6106) followed by the DAB substrate [18].

Image Calibration: Staining was captured using a 4×, 10×, 20× or 40× objective (×40 or ×100 or ×200 or ×400 magnification) from at least four non-overlapping microscopic fields by an AxioCam CCD digital camera (Carl Zeiss). Files were saved in a 12-bit tagged image file format (.tif). To perform area analysis, unmodified, uncompressed. tif image files of staining were accessed in Photoshop as previously described [19].

2.6.1. Statistical analysis of immunohistochemistry data

We conducted quantitative analysis of vasculature using ImageJ software. The observer was blinded to experimental group, and using systematic random sampling, at least three non-overlapping regions within the labyrinthine layer from each placental section (40× magnification images) were analyzed. Control, 25% FR, and 50% placentas (n=8/group) were evaluated and standardized for equal pixel size. For vascular quantification, CD34 positively stained cells were identified and contiguous positively stained cells were marked to create an outline of the vascular area. Region of interest analysis was conducted to calculate the summative area of positively outlined areas per region.

Because of the pattern of distribution of positive staining, semi-quantitative analysis of IL10 (n=4-7/group) and trophoblast staining (n=8/group) was conducted by a pathologist blinded to phenotypic information. Staining was quantified by grading the overall positive staining of cells with intensities of 0 to 4 akin to a Likert scale (0=below the level of detection, 1=weak, 2=mild, 3=moderate, 4=strong) [20].

Quantitative analysis of LC3B staining was performed by counting the number of positively- and non-staining spongiotrophoblast cells per region of interest, located in the junctional zone. All cell counts were completed in triplicate on randomly selected fields (taken at 40×) per placental section and average cell counts calculated for each mouse placenta (n=3-4/group).

2.7. Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted in GraphPad Prism software (version 5, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) and data are presented as means ± SEM. Significant differences between three groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher's LSD, unless otherwise indicated (for qRT-PCR and western blotting studies). Post-hoc Tukey's multiple comparison testing was used to determine significant differences in pairwise comparisons. When comparisons were made between two groups only, Student's t-test was performed. All p-values are reported as 2-tailed with statistical significance set at <0.05 for all comparisons. Sample sizes were based upon previously published data evaluating placental gene expression using this murine model of maternal FR resulting in IUGR [7]. Power analyses conducted using gene expression data (by qRT-PCR) from that study, which showed mean relative expression=1.0 with SD=0.1, indicate that 5-8 animals per experimental group was sufficient to detect a 25-35% change in gene expression from the control group. These sample sizes achieve 89% power to detect a difference of at least 25-35% using the Hsu (with Best) multiple comparison test at a 0.05 overall significance level.

3. Results

3.1 Placenta and embryo weight

Compared to controls (n=20), 25% FR mice (n=25) did not demonstrate a decrease in placental weight. However, 50% FR mice (n=21) demonstrated a significant (p<0.01) decrease in placental weight compared to control and 25% FR mice (control: 0.08±0.002g versus 25% FR: 0.08±0.002g versus 50% FR: 0.06±0.002g). The 50% FR mice displayed a 29% decrease in placental weight compared to the control and a 31% reduction compared to the 25% FR mice. Both the 25% FR mice and 50% FR mice showed a significant (p<0.01) decrease in embryo weight compared to controls (25% FR: 42% decrease; 50% FR: 48% decrease) (control: 1.16±0.02g versus 25% FR: 0.67±0.01g versus 50% FR: 0.61±0.03g). There was no significant difference in embryo weight between 25% and 50% FR mice.

3.2 RNA sequencing pathway analysis in placental tissue

There were almost 700 genes that were differentially expressed between 50% FR and control groups, as previously reported [7]. Approximately 15% of these genes have unknown clinical significance in human physiology or disease. Of the remainder, approximately 7% of the genes that had differential RNA expression in the 50% FR group compared to controls have been associated with immunologic function, vascular and endothelial maintenance, inflammation, autophagy, or ER stress (Table 2).

Table 2. Genes differentially expressed between control and 50% FR groups by RNA sequencing that are involved in vascular, immunological and inflammatory pathways.

Five placentas from control and five placentas from 50% FR mice were processed for RNA sequencing. This table represents the candidate genes identified as differentially expressed between control and 50% FR groups, by unadjusted p-value<0.05, involved in immunologic, inflammatory and vascular pathways. For each gene listed, average expression level for the control and 50% FR group is reported, as well as log2 fold change, p-value based upon Student's t-test and adjusted p-value using Bonferroni correction between groups. Genes are grouped by functional roles in innate immunity, vascular and endothelial function, inflammation, autophagy and ER stress.

| Gene | Average Expression Level (control) | Average Expression Level (50% FR) | Log2 Fold Change | P-value | P-value (adj) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innate Immunity | IL21r (interleukin 21 receptor) | 1.056 | 0.346 | -1.6 | 7.73E-08 | 0.001 |

| IL23r (interleukin 23 receptor) | 0.366 | 0.078 | -2.2 | 9.11E-06 | 0.042 | |

| Marco (macrophage receptor with collagenous structure) | 0.019 | 0.856 | 5.5 | 0.0002 | 0.187 | |

| Cebpa (CCAAT/enhancer binding protein, alpha) | 6.306 | 9.708 | 0.62 | 0.008 | 1 | |

| Sfrp1 (secreted frizzled-related protein 1) | 1.199 | 0.844 | -0.5 | 0.015 | 1 | |

| Syt11 (synaptotagmin XI) | 1.481 | 1.080 | -0.45 | 0.015 | 1 | |

| Siglec1 (sialic acid binding Ig-like lectin 1, sialoadhesin) | 0.660 | 1.132 | 0.78 | 0.033 | 1 | |

| Pyhin1 (pyrin and HIN domain family, member 1) | 0.300 | 0.564 | 0.91 | 0.034 | 1 | |

| Isg15 (ISG15 ubiquitin-like modifier) | 20.849 | 34.689 | 0.73 | 0.045 | 1 | |

| Vascular and endothelial maintenance | Tnfsf15 (tumor necrosis factor superfamily, member 15) | 0.072 | 0.019 | -1.9 | 4.03E-05 | 0.075 |

| Gm52 (syncytin a) | 17.555 | 32.574 | 0.89 | 0.0007 | 0.339 | |

| Wls (wntless homolog) | 14.802 | 9.686 | -0.61 | 0.0007 | 0.339 | |

| Ncf1 (neutrophil cytosolic factor 1) | 0.322 | 0.598 | 0.89 | 0.001 | 0.412 | |

| Bmper (BMP-binding endothelial regulator) | 6.383 | 11.646 | 0.87 | 0.004 | 0.737 | |

| Map3k6 (mitogen activated protein kinase 6) | 1.823 | 2.862 | 0.65 | 0.006 | 0.981 | |

| Lyve1 (lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronic receptor 1) | 11.950 | 23.472 | 0.97 | 0.012 | 1 | |

| Cldn5 (claudin 5) | 7.497 | 11.338 | 0.60 | 0.013 | 1 | |

| Ntsr1 (neurotensin receptor 1) | 0.349 | 0.067 | -2.4 | 0.016 | 1 | |

| C5ar1 (complement component 5a receptor 1) | 0.257 | 0.535 | 1.1 | 0.021 | 1 | |

| Kcnk6 (potassium inwardly-rectifying channel, K6) | 3.905 | 2.975 | -0.39 | 0.029 | 1 | |

| Lrg1 (leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein 1) | 2.044 | 3.732 | 0.87 | 0.035 | 1 | |

| Ucp2 (uncoupling protein 2, mitochondrial, proton carrier) | 11.918 | 16.672 | 0.48 | 0.035 | 1 | |

| Trpv6 (transient receptor potential cation channel, V6) | 9.530 | 5.234 | -0.86 | 0.049 | 1 | |

| Gclm (glutamate-cysteine ligase, modifier subunit) | 6.098 | 8.718 | 0.52 | 0.049 | 1 | |

| Inflammation | Mmp8 (matrix metallopeptidase 8) | 0.198 | 0.561 | 1.5 | 2.77E-05 | 0.070 |

| Sfxn5 (sideroflexin 5) | 0.495 | 0.325 | -0.61 | 0.008 | 1 | |

| Slfn4 (schlafen 4) | 0.433 | 0.736 | 0.77 | 0.010 | 1 | |

| IL18rap (interleukin 18 receptor accessory protein) | 0.233 | 0.144 | -0.70 | 0.011 | 1 | |

| Tnf (tumor necrosis factor) | 0.338 | 0.176 | -0.94 | 0.012 | 1 | |

| Bok (Bcl2-related ovarian killer protein) | 51.091 | 38.383 | -0.41 | 0.025 | 1 | |

| Fpr2 (formyl peptide receptor 2) | 0.149 | 0.354 | 1.25 | 0.027 | 1 | |

| Plxnc1 (plexin C1) | 0.142 | 0.238 | 0.74 | 0.032 | 1 | |

| Blnk (B-cell linker) | 0.485 | 0.742 | 0.61 | 0.043 | 1 | |

| C1qa (complement component 1, q subcomponent, alpha polypeptide) | 5.333 | 10.883 | 1.03 | 0.049 | 1 | |

| Autophagy | Fbxo32 (f box protein 32) | 23.176 | 13.730 | -0.76 | 0.005 | 0.808 |

| Scd1 (stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase 1) | 5.818 | 4.339 | -0.42 | 0.017 | 1 | |

| Dram1 (DNA damage regulated autophagy modulator 1) | 10.696 | 7.794 | -0.46 | 0.009 | 1 | |

| ER stress | Creld2 (cysteine-rich with EGF like domains 2) | 42.240 | 27.444 | -0.62 | 0.003 | 0.724 |

| Derl3 (Der1-like domain family, member 3) | 23.324 | 14.517 | -0.68 | 0.019 | 1 | |

| Pdia4 (protein disulfide isomerase associated 4) | 82.834 | 60.377 | -0.46 | 0.010 | 1 |

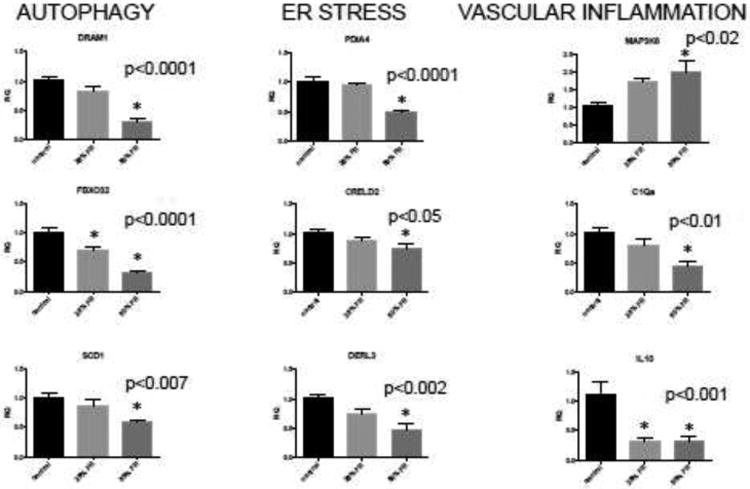

3.3 qRT-PCR

In order to extend the results found by RNA sequencing to the 25% FR group, we utilized qRT-PCR to determine gene expression in all groups, with a focus on genes involved in autophagy, ER stress and inflammation in human disease. We validated differences in expression between control, 25% FR and 50% FR groups (n=6/group) for three genes involved in autophagy, Dram1 (control: 1.009±0.059 versus 25% FR: 0.816±0.094 versus 50% FR: 0.301±0.062; p<0.001), Fbxo32 (control: 1.010±0.062 versus 25% FR: 0.708±0.046 versus 50% FR: 0.305±0.046; p<0.001), and Scd1 (control: 1.012±0.067 versus 25%FR: 0.851÷0.114 versus 50% FR: 0.581±0.048; p<0.006). Three genes which are known to be functionally important in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response, Pdia4, Creld2, and Derl3 were also significantly differentially expressed between groups (control: 1.014±0.075 versus 25% FR: 0.955±0.038 versus 50% FR: 0.493±0.038; p<0.0001), (control: 1.009±0.057 versus 25% FR: 0.885±0.054 versus 50% FR: 0.738±0.089; p<0.04), (control: 1.007±0.073 versus 25% FR: 0.746±0.078 versus 50% FR: 0.479±0.091; p<0.001), respectively. Lastly, two genes involved in vascular inflammation were found to be differentially expressed, Map3k6 (control: 1.030±0.084 versus 25% FR: 1.697±0.120 versus 50% FR: 2.000±0.305; p<0.02) and C1qa (control: 1.022±0.088 versus 25% FR: 0.804±0.096 versus 50% FR: 0.459±0.059; p<0.0008) (Fig 2). In addition, given the key anti-inflammatory role of IL10 in pregnancy, we quantitated its expression and found that Il10 levels in whole placenta decreased in FR compared to control groups (control: 1.113±0.214 versus 25% FR: 0.328±0.058 versus 50% FR: 0.320±0.072; p<0.001).

Figure 2. qRT-PCR validation of placental RNA expression of genes involved in vascular inflammation, autophagy and ER stress in mice exposed to maternal FR.

For each candidate gene, average mRNA expression level from control, 25% FR, and 50% FR groups (n=6/group, based on power calculations for detect a 25% difference in mean expression between groups to achieve 89% power at a 0.05 overall significance level) was calculated by qRT-PCR. Data are represented in graphs as means ± SEM. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between indicated FR group compared to control (p<0.05) by post-hoc Tukey's multiple comparison testing. Reported p-value for each gene is by one-way ANOVA between all three groups.

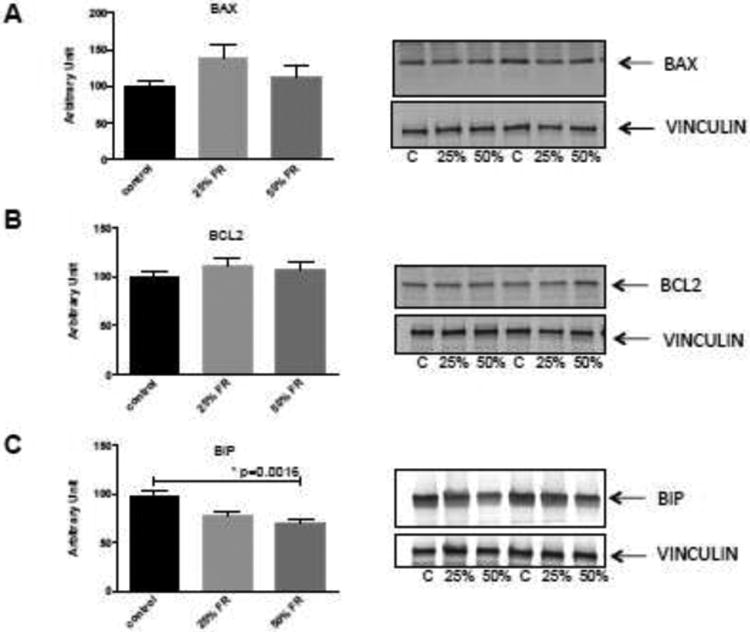

3.4 Western immunoblotting

Our results above suggested that FR results in alterations to autophagy and ER stress pathways. To translate these differences, BAX, BCL2, and BIP protein expression were assessed by Western blot analysis. There was no significant difference in BAX (p=0.19) or BCL2 (p=0.46) protein expression among groups (Fig 3A,3B). However, BIP expression was down regulated in FR groups (control: 97.62±5.94 versus 25% FR: 77.46±4.71 versus 50% FR: 69.21±4.60; p=0.0016) (Fig 3C). As a marker of generalized ER stress, this observation is consistent with our qPCR findings of decreasing ER stress with increasing severity of food restriction.

Figure 3. Western immunoblotting of apoptosis and ER stress markers in the placentas of gestational FR-exposed mice.

Representative blots of BAX (A), BCL2 (B) proteins as markers of apoptosis, and BIP (C) as a marker of ER stress are shown. There were no significant differences between groups for BAX and BCL2 expression. BIP expression however, was decreased in both the 25% and 50% FR groups, compared to controls. Data are represented in graphs as means ± SEM. Asterisk indicates p<0.05 by ANOVA. C=control, 25%=25% FR group, 50%=50% FR group (n=9/group).

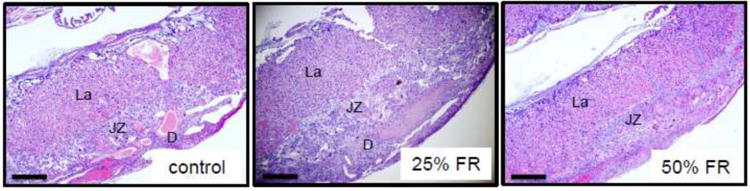

3.5 Placental histopathology

Histopathology was undertaken to evaluate for differences in placental structures among groups. No appreciable differences were seen between groups in the overall architectural organization of the placenta as visualized by H&E staining (Fig 4).

Figure 4. Hematoxylin & eosin staining of control, mild and moderate FR mouse placentas at 4× magnification.

Representative murine placental sections stained by H&E from control, mild- and moderate-FR exposed mice (n=8/group). La: labyrinth; JZ: junctional zone; D: decidua. Scale bars represent 500μm.

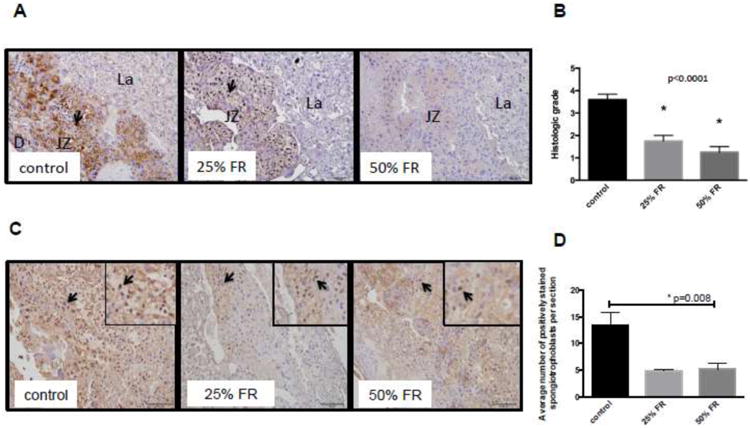

IL10 and LC3B immunostaining was performed to evaluate for protein-level expression of inflammatory markers and bulk autophagy. Positive staining for IL10 was seen predominantly within the junctional zone of the placenta (Fig 5A), and overall positive staining for IL10 was decreased with increasing degrees of food restriction (control: 3.60±0.24 versus 25%FR: 1.75±0.25 versus 50% FR: 1.25±0.25; p<0.0001) (Fig 5B). Similarly, positive staining for LC3B was seen predominantly within the junctional zone, and detected in mostly spongiotrophoblast cells, though occasionally seen in giant trophoblast cells (Fig 5C). Overall numbers of spongiotrophoblasts and giant cell trophoblasts (determined by morphology) were not different between groups (p=0.38 and p=0.81, respectively). Average number of LC3B-positively staining spongiotrophoblast cells per section (using region of interest analysis) was significantly different between groups (control: 13.44±2.39 versus 25% FR: 4.89±0.29 versus 50% FR: 5.17±1.18, p=0.0087) (Fig 3D).

Figure 5. IL10 and LC3B staining in murine placenta after maternal FR.

(A) Representative sections from each group (control, 25% FR, 50% FR) stained for IL10 demonstrate decreasing positive staining for IL10 (brown; 20× magnification) with increasing severity of maternal FR. Arrows indicate positive staining. Scale bars represent 100 μm. D: decidua; JZ: junctional zone; La: labyrinth. (B) Decreasing histologic grading scores of overall positively of IL10 staining in FR groups compared to controls (n=4-7/group). Data are represented in graphs as means ± SEM. Asterisks indicate p<0.0001 between the indicated group compared to the control group, by post-hoc Tukey's multiple comparison testing. Listed p-value represents significance between groups, by ANOVA. (C) Representative sections from each group (control, 25% FR, 50% FR) stained for LC3B (brown; 20× magnification) demonstrating decreasing numbers of positively-stained spongiotrophoblasts in the junctional zone of FR mouse placenta with increasing severity of FR. Arrows indicate positive staining of spongiotrophoblasts. Scale bars represent 100μm. (D) Decreased average numbers of positively staining spongiotrophoblasts for LC3B per region of interest in FR groups compared to controls (n=3-4/group). Data are represented in graphs as means ± SEM. Asterisk indicates p<0.05 between all groups, by ANOVA.

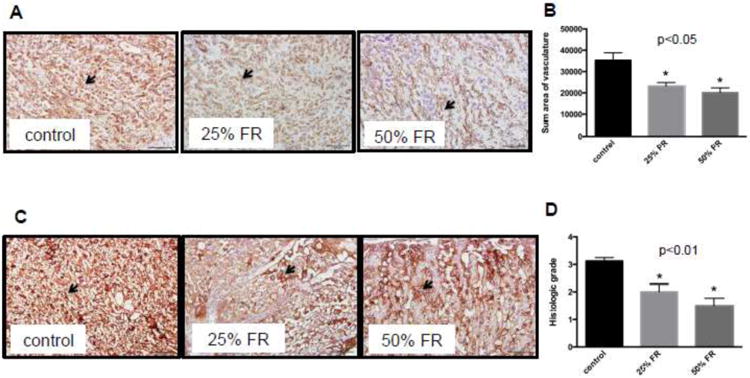

Evaluation of vascular and trophoblast structures was specifically undertaken, as these structures are essential for nutrient provision from the mother to the fetus. Within the labyrinthine area, FR mice showed a graded decrease in vasculature with increasing severity of FR, as analyzed by CD34 immunohistochemical analysis (Fig 6A). When summative area of vasculature per region of interest was compared, there was a significant decrease in both FR groups compared to controls (control: 35264±3530 versus 25% FR: 23224±1623 versus 50% FR: 20156±2193; p<0.01) (Fig 6B). Overall trophoblast integrity was altered in the FR mice, as demonstrated by pan cytokeratin immunohistochemistry staining (Fig 6C). Sections were graded 0 to 4+ on overall positivity of staining, and there was a significant difference between groups (control: 3.125±0.125 versus 25% FR: 2.000±0.267 versus 50% FR: 1.500±0.267; p<0.01) (Fig 6D). Qualitative review revealed degenerative changes of the cytokeratin-positively staining structures with a decreased percentage of positively stained cells overall in FR groups compared to control.

Fig 6. Vascular and trophoblast changes in the murine placenta with maternal FR.

(A) Representative sections from each group (control, 25% FR, 50% FR) stained for CD34 (brown; 20× magnification) in endothelial cells within the labyrinthine region (20×). Arrows indicate blood vessels. Scale bars represent 100μm. (B) Quantitative analysis of sum of vascular area per region of interest at 40×. Each placental section from all three groups (n=8/group) was analyzed in triplicate. Vascular areas were defined as outlined by contiguous positively stained cells. Data are represented in graphs as means ± SEM. Asterisks indicate p<0.05 (between indicated FR group and control), by post-hoc Tukey's multiple comparison testing. Listed p-value indicates significance between all groups, by ANOVA. (C) Representative placental sections from each group (control, 25% FR, 50% FR) stained for trophoblast cells using cytokeratin (brown, 20× magnification). Qualitatively, degenerative changes (dilated maternal spaces, with a decreased percentage of positive stained cells in the 25% and 50% FR groups compared to controls) are seen in murine trophoblast layers within the labyrinth. Arrows indicate trophoblast lining. Scale bars represent 100μm. (D) Decreased histologic grading scores of overall positivity of cytokeratin stain in FR groups compared to controls (n=8/group). Data are represented in graph as means ± SEM. Asterisks indicate p<0.01 between indicated FR group vs. control, by post-hoc Tukey's multiple comparison testing. Listed p-value indicates significance between all groups, by ANOVA.

4. Discussion

Our animal study demonstrates that maternal nutrient deprivation during pregnancy affects the immunologic milieu in the placenta, specifically affecting both gene and protein expression of IL10 and associated cellular stress responses to nutrient deprivation via autophagy and ER stress. Our findings are consistent with our hypothesis that IL10 expression is decreased in maternal food-restricted placentas. These findings are in line with human data showing that placental insufficiency uniformly seen in various disorders of pregnancy such as recurrent miscarriages, preeclampsia, and/or intrauterine growth restriction may be due to disordered immune tolerance and/or dysregulation of IL10 [11,21-23].

IL10 is a known key anti-inflammatory cytokine in pregnancy, but has been shown in other inflammatory human disease to also regulate autophagic and ER stress responses. In our model, we provide evidence that bulk measures of autophagy and ER stress are suppressed at the junctional zone of the murine placenta in conditions of maternal food restriction. These findings are contradictory to our hypothesis that IL10 reduction leads to increased cellular death via autophagy and ER stress. Instead, these findings suggest that placental cell populations adapt to chronic nutrient restriction by decreasing cellular autophagic and ER stress responses in order to continue to function and survive to provide nutrients and blood flow to the growing fetus. We identified, by RNA sequencing and pathway analysis, novel genes important in these cell homeostasis regulatory pathways that are differentially affected by maternal food restriction. However, the suppression of autophagy, ER stress, and anti-inflammatory signals localized largely to the junctional zone in maternal FR-associated placentas does not adequately compensate for dysregulation of vascular and trophoblast structures within the murine labyrinth.

Autophagy is the process by which damaged organelles and protein aggregates are engulfed into autophagosomes, fused with lysosomes and degraded by hydrolases. This process is essential for cell survival and regulation of energy and nutrient homeostasis. Therefore, we had hypothesized that in our model of maternal food restriction and intrauterine growth restriction, markers of autophagy would be increased. However, we found the opposite – that bulk measures of autophagy are decreased. These contradictory findings are in line with the existing debate on whether placental insufficiency leads to induction or suppression of autophagy as some groups have shown that up-regulation of autophagy is associated with fetal growth restriction and preeclampsia [24-26]. It is generally accepted that both in vivo and in vitro, starvation conditions activate autophagy. However, these responses are highly tissue-specific, and modulated by multiple and complex input signals. The placenta is a unique organ that is responsible for sustenance of the growing fetus, often at the expense of maternal well-being, and therefore, may regulate autophagic processes differently in response to nutrient deprivation.

Our results in placentas associated with FR overall suggest that bulk autophagy is decreased, especially in the junctional zone of the murine placenta. We believe that this seemingly contradictory finding may reflect the function of certain autophagy genes to inhibit inflammation, as seen in tissue-specific knock-out animal models of autophagy genes resulting in wide spread tissue over-inflammation [27,28]. In fact, in in vivo cancer models, autophagy inhibition has been demonstrated to favor immunosuppression, leading to increased tumor aggressiveness [29]. If this is also true in pregnancy at the maternal-fetal interface, our results suggests that the autophagic suppression seen in the FR-associated placentas may represent a compensatory mechanism to maintain pregnancy in the face of a pro-inflammatory environment.

By RNA sequencing, we identified a number of autophagic genes that may be suppressed in IUGR induced by maternal food restriction. For example, Dram1, or DNA-damage regulated autophagy modulator 1, is a gene regulated as part of the p53 tumor suppressor pathway that encodes a lysosomal membrane protein required for the induction of autophagy via this pathway. In our murine FR-associated placentas, Dram1 expression was significantly decreased compared to controls implying suppressed autophagy via this pathway. This is in contrast to reports by Hung et al, who found increased levels of DRAM in human IUGR placentas [24]. Fbxo32, or F box protein 32 (also known as atrogin-1), deficiency in a knock-out animal model has been associated with premature death of cardiomyocytes via impaired autophagy [30]. In our model, FR led to decreased production of Fbxo32, perhaps affecting autophagy-induced cell death. Scd1, stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1, is a key player in fatty acid biosynthesis. Therefore, its reduction in our FR groups may simply represent poor maternal nutrient supply. However, inhibition of Scd1 has been shown to reduce starvation-induced autophagy [31]. Therefore, the reduced levels of Scd1 seen in FR groups may reflect compensation in these placentas to reduce the induction of autophagy by starvation.

ER stress is the disruption of protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum, resulting in the accumulation of misfolded proteins within the ER. This pathologic process results from disturbances such as ER calcium depletion, nutrient deprivation, oxidative stress, DNA damage, or energy perturbation. When ER stress is persistent and excessive, the unfolded protein response (UPR) initiates apoptosis to eliminate stressed cells and also activates NF-κB and the inflammasome. ER stress has been implicated as a contributor to pathology in human intrauterine growth restriction, likely due to deficient placental perfusion inducing oxidative stress [32-35]. Again, our findings are contradictory to our hypothesis that ER stress increases in the nutritionally inadequate environment of IUGR. In our study, overall protein expression of BIP decreases with increasing severity of maternal FR, with no change in apoptotic markers between groups. This finding may again be related to the unique ability of the placenta to immunologically mediate stress responses in order to maintain cellular viability and function to protect and provide for the developing fetus.

IL10 has been found to modulate ER stress in other inflammatory disorders [36-37], but its role in placental ER stress has not been defined. By RNA sequencing, we have discovered 3 novel markers of ER stress that are differentially expressed in placentas of food-restricted mothers. We demonstrate decreased levels of Pdia4 (also known as ERP72), a mediator of the unfolded protein response, in FR groups compared to control mice. We also demonstrated decreased levels of Creld2, a stress-inducible gene that may regulate the ER stress response and progression. Mutations in promoter sites of this gene result in decreased basal activity and responsiveness to ER stress stimuli using luciferase reporter analyses [38]. Lastly, Derl3 was found to have decreased expression in FR placentas. Derl3 encodes an important component of ER-associated degradation. In vitro studies have demonstrated that overexpression of this gene enhances ER stress responses and promotes cellular survival, whereas decreased expression decreases ER response but increased cell death in response to ischemia [39]. Taken together, the decreased expression of these 3 genes would result in decreased functional ER stress activity in the face of nutritional deprivation.

Lastly, the protective effects of IL10 on vascular function and inflammation have been observed both in pregnancy models and non- pregnancy states [22-23]. IL10 knockout mice have been shown to exhibit impaired spiral artery remodeling and poor placental angiogenesis, resulting in IUGR, when exposed to environmental toxins. Treatment with recombinant IL10 rescues the pregnancy, seemingly via restoration of endovascular activity [40]. Outside of pregnancy, IL10 has also been implicated as a mediator of vascular protection in hypertension, diabetes and atherosclerosis [41-43]. Therefore, one interesting consequence of disordered IL10 seen in adverse pregnancy outcomes is that it may be involved in vascular remodeling seen in placental insufficiency and the developmental programming of cardiovascular disease seen in the offspring of pregnancies complicated by IUGR, preeclampsia, or prematurity. An interesting candidate gene that was greatly increased in FR placentas is Map3k6 (mitogen-activated protein 3 kinase 6), which mediates angiogenic and tumorigenic effects via VEGF expression [44]. Again, this increase may represent an attempt at compensation for poor placental vascularization secondary to nutritional restriction-induced remodeling, as is evident by our immunohistochemical staining for CD34+ endothelial cells. We also demonstrated decreased levels of C1qa, a polypeptide chain of complement subcomponent C1q. Complement C1q-induced activation of β-catenin signaling has recently been shown to contribute to hypertensive arterial remodeling [45]. Contrary to our expectations, C1qa levels were decreased in our FR placentas, again highlighting the inconsistencies of whether cellular protective mechanisms are impaired or enhanced in response to adverse environments in these pathologic conditions of pregnancy.

Our histopathologic findings were consistent with the reported placental findings in human IUGR [46-47], where placental hypovascularity and trophoblast degeneration lead to poor blood flow and nutrient transfer to the fetus [48]. However, it should be noted that despite decreased vascularity and damaged trophoblast layers within the labyrinthine area of FR-associated placentas, placental weight was not changed. It may be that in mild FR, placental mass is relatively maintained at the expense of fetal growth, whereas moderate FR crosses a critical threshold, beyond which placental self-preservation is impaired. Taken together, our histopathologic data suggests that alterations in immune tolerance, and placental compensatory responses to protect cellular health via decreasing autophagic and ER stress responses, may allow for functional compensation at mild levels of FR, but are inadequate at more moderate levels of FR.

There are several strengths and limitations to our study. The use of animal models to study human disease is often necessary in diseases like IUGR, where detection occurs late in the course of disease making progression of disease difficult to study. However, careful consideration into the specific animal model chosen is essential, as there are both similarities and differences to human placental structure and pregnancy with any animal model [49,50]. Though both mouse and human placentas are hemochorial, meaning fetally-derived trophoblasts are directly bathed in maternal blood [48], there are significant differences in gestation and litter size, which may explain why human pregnancies demonstrate much greater adaptive capacity in protecting fetal weight. These differences present a major limitation of our study, as the extent to which animal data can be applied to human disease remains under debate. We specifically chose this mouse model of late chronic maternal food restriction as it has been shown to result in IUGR, and it has been well-characterized in its effect of maternal health and hormonal status during pregnancy, nutrient transfer to the fetus, and short- and long-term effects on the offspring [7,48,51]. However, as stated previously, architectural differences in mouse and human placenta present challenges in comparing changes specific to the nutrient exchange layers. To address this, we utilized a discovery-based technique of RNA sequencing to identify patterns of placental gene expression changes that may be altered in growth restriction. This allows for a non-biased evaluation of how specific genes involved in immunologic function and cellular maintenance are affected in IUGR, and identification of potentially novel players in placental insufficiency.

Using whole placenta, we found 700 genes that were significantly differentially expressed between groups, and performed pathway analysis, which demonstrated that the pathways of interest were well represented among the differentially expressed genes. However, another limitation of our study was that adjusted p-values from RNA sequencing analysis were nonsignificant in some of our genes of interest involved in immunologic pathways. This limitation may have occurred because of the smaller sample sizes used for RNA sequencing. This sample size was chosen as genome-wide sequencing techniques applied to large groups can be cost-prohibitive, and the main purpose of RNA sequencing in this study was to screen for pathway changes. To address this issue on a gene-specific basis, we validated RNA expression of specific genes of interest by qRT-PCR using larger sample sizes across all three experimental groups. In addition, there is still significant debate and remaining unknowns in the field on the crosstalk between autophagy, ER stress and apoptotic pathways. Our study does not establish cause-and-effect, and further mechanistic studies on these pathways in IUGR are warranted to more definitively link decreased IL10 with autophagy and ER stress.

In conclusion, our murine model of chronic, mild to moderate late gestational FR of the pregnant mouse represents an animal model of IUGR with reasonable fidelity to the human condition, based on histopathologic similarities. Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that IL10 expression in the murine placenta is decreased in maternal gestational food restriction. Using RNA sequencing techniques, we have demonstrated that a significant portion of gene expression changes seen on a whole placental level involve immunologic pathways and associated cellular maintenance processes. However, contrary to our hypothesis that maternal FR results in increased autophagy and ER stress, leading to cellular death, we found that bulk measures of these pathways are decreased in maternal FR-associated placentas. We believe that these findings suggest that the placenta serves as a unique interface, that must preserve fetal growth in the face of adverse maternal environment, and that these mechanisms are immunologically mediated. As such, placental compensatory responses appear to be distinct and opposite to the inflammatory, autophagic and ER stresses described in in vitro nutrient deprivation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the UCLA Children's Discovery and Innovation Institute [CDI-SGA-01012016 (AC)], the American Heart Association [15BGIA25710060 (AC)], and the National Institutes of Health [5K12HD034610, HD 081206, HD 41230 (SUD)].

Abbreviations

- BAX

Bcl-2 associated X protein

- BCL2

B-cell lymphoma

- BIP

Binding immunoglobulin protein

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- GD

gestational day

- FR

food restriction

- IL10

interleukin 10

- IUGR

intrauterine growth restriction

- LC3B

microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 beta

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Madhuri Wadehra, Email: mwadehra@mednet.ucla.edu.

Matteo Pellegrini, Email: matteop@mcdb.ucla.edu.

References

- 1.Cross JC, Hemberger M, Lu Y, Nozaki T, Whitely K, Masutani M, Adamson SL. Trophoblast functions, angiogenesis and remodeling of the maternal vasculature in the placenta. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;187(1-2):207–12. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herr F, Baal N, Widmer-Teske R, McKinnon T, Zygmunt M. How to study placental vascular development? Theriogenology. 2010;73(6):817–27. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanaka-Gantenbein C. Fetal origins of adult diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1205:99–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thornburg KL, O'Tierney PF, Louey S. Review: the placenta is a programming agent for cardiovascular disease. Placenta. 2010;31(Suppl):S54–9. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ligi I, Grandvuillemin I, Andres V, Dignat-George F, Simeoni U. Low birth weight infants and the developmental programming of hypertension: a focus on vascular factors. Semin Perinatol. 2010;34(3):188–192. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luyckx VA, Bertram JF, Brenner BM, Fall C, Hoy WE, Ozanne SE, Vikse BE. Effect of fetal and child health on kidney developmental and long-term risk of hypertension and kidney disease. Lancet. 2013;382:273–83. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen PY, Ganguly A, Rubbi L, Orozco LD, Morselli M, Ashraf D, Jaroszewicz A, Feng S, Jacobsen SE, Nakano A, Devaskar SU, Pellegrini M. Intrauterine calorie restriction affects placental DNA methylation and gene expression. Physiol Genomics. 2013;45(14):565–76. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00034.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gabory A, Ferry L, Fajardy I, Jouneau L, Gothié JD, Vigé A, Fleur C, Mayeur S, Gallou-Kabani C, Gross MS, Attig L, Vambergue A, et al. Maternal diets trigger sex-specific divergent trajectories of gene expression and epigenetic systems in mouse placenta. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e47986. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mao J, Zhang X, Sieli PT, Falduto MT, Torres KE, Rosenfeld CS. Contrasting effects of different maternal diets on sexually dimorphic gene expression in the murine placenta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(12):5557–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000440107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biswas S. Placental changes in idiopathic intrauterine growth restriction. OA Anatomy. 2013;1(2):11. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng SB, Sharma S. Interleukin-10: a pleitropic regulator in pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2015;73(6):487–500. doi: 10.1111/aji.12329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thamotharan S, Stout D, Shin BC, Devaskar SU. Temporal and spatial distribution of murine placental and brain GLUT3-luciferase transgene as a readout of in vivo transcription. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304(3):E254–66. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00214.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzbery SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–11. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11(10):R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganguly A, McKnight RA, Raychaudhuri S, Shin BC, Ma Z, Moley K, Devaskar SU. Glucose transporter isoform-3 mutations cause early pregnancy loss and fetal growth restriction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292(5):E1241–55. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00344.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sankar R, Thamotharan S, Shin D, Moley KH, Devaskar SU. Insulin-responsive glucose transporters-GLUT8 and GLUT4 are expressed in the developing mammalian brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2002;107(2):157–65. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00487-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wadehra M, Natarajan S, Seligson DB, Williams CJ, Hummer AJ, Hedvat C, et al. Expression of epithelial membrane protein-2 is associated with endometrial adenocarcinoma of unfavorable outcome. Cancer. 2006;107:90–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agley CC, Velloso CP, Lazarus NR, Harridge SD. An image analysis method for the precise selection and quantitation of fluorescently labeled cellular constituents: application to the measurement of human muscle cells in culture. J Histochem Cytochem. 2012;60(6):428–38. doi: 10.1369/0022155412442897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klopfleisch R. Multiparametric and semiquantitative scoring systems for the evaluation of mouse model histopathology – a systematic review. BMC Vet Res. 2013;9:123. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-9-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tinsley JH, South S, Chiasson VL, Mitchell BM. Interleukin-10 reduces inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and blood pressure in hypertensive pregnant rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298(3):R713–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00712.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chatterjee P, Chiasson VL, Kopriva SE, Young KJ, Chatterjee V, Jones KA, Mitchell BM. Interleukin 10 deficiecy exacerbates toll-like receptor 3-induced preeclampsia-like symptoms in mice. Hypertension. 2011;58(3):489–96. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.172114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chatterjee P, Chiasson VL, Seerangan G, Tobin RP, Kopriva SE, Newell-Rogers MK, Mitchell BM. Cotreatment with interluekin 4 and interleukin 10 modulates immune cells and prevents hypertension in pregnant mice. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28(1):135–42. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hung TH, Chen SF, Lo LM, Li MJ, Yeh YL, Hsieh TT. Increased autophagy in placentas of intrauterine growth-restricted pregnancies. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oh SY, Choi SJ, Kim KH, Cho EY, Kim JH, Roh CR. Autophagy-related proteins, LC3 and Beclin-1, in placentas from pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia. Reprod Sci. 2008;15(9):912–20. doi: 10.1177/1933719108319159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saito S, Nakashima A. A review of the mechanism for poor placentation in early-onset preeclampsia: the role of autophagy in trophoblast invasion and vascular remodeling. J Reprod Immunol. 2014;101-102:80–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park S, Buck MD, Desai C, Zhang X, Loginicheva E, Martinez J, Freeman ML, Saitoh T, Akira S, Guan JL, He YW, Blackman MA, et al. Autophagy genes enhance murine gammaherpervirus 68 reactivation from latency by preventing virus-induced systemic inflammation. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19(1):91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu Q, Yokoyama CC, Williams JW, Baldrge MT, Jin X, DesRochers B, Bricker T, Wilen CB, Bagaitkar J, Logincheva E, Sergushichev A, Kreamalmeyer D, et al. Homeostatic control of innate lung inflammation by vici syndrome gene Epg5 and additional autophagy genes promotes influenza pathogenesis. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19(1):102–13. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ladoire S, Enot D, Senovilla L, Ghiringhelli F, Poirier-Colame V, Chaba K, Semeraro M, Chaix M, Penault-Liorca F, Arnould L, Poillot ML, Arveux P, et al. The presence of Lc3b puncta and hmgb1 expression in malignant cells correlate with the immune infiltrate in breast cancer. Autophagy. 2016 doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1154244. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zaglia T, Milan G, Ruhs A, Franzoso M, Bertaggia E, Pianca N, Carpi A, Carullo P, Pesce P, Sacerdoti D, Sarais C, Catalucci D, et al. Atrogin-1 deficiency promotes cardiomyopathy and premature death via impaired autophagy. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(6):2410–24. doi: 10.1172/JCI66339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogasawara Y, Itakura E, Kono N, Mizushima N, Arai H, Nara A, Mizukami T, Yamamoto A. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 activity is required for autophagosome formation. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(34):23938–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.591065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burton GJ, Yung HW, Cindrova-Davies T, Charnock-Jones DS. Placental endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress in the pathophysioloy of unexplained intrauterine growth restriction and early onset preeclampsia. Placenta. 2009;30(Suppl A):S43–8. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawakami T, Yoshimi M, Kadota Y, Inoue M, Sato M, Suzuki S. Prolonged endoplasmic reticulum stress alters placental morphology and causes low birth weight. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2014;275(2):134–44. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lian IA, Løset M, Mundal SB, Fenstad MH, Johnson MP, Eide IP, Bjørge L, Freed KA, Moses EK, Austgulen R. Increased endoplasmic reticulum stress in decidual tissues from pregnancies complicated by fetal growth restriction with and without pre-eclampsia. Placenta. 2011;32(11):823–9. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yung HW, Calabrese S, Hynx D, Hemmings BA, Cetin I, Charnock-Jones DS, Burton GJ. Evidence of placental translation inhibition and endoplasmic reticulum stress in the etiology of human intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Pathol. 2008;173(2):451–62. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hasnain SZ, Tauro S, Das I, Tong H, Chen AC, Jeffery PL, McDonald V, Florin TH, McGuckin MA. IL-10 promotes production of intestinal mucus by suppressing protein misfolding and endoplasmic reticulum stress in goblet cells. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(2):357–368. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shkoda A, Ruiz PA, Daniel H, Kim SC, Rogler G, Sartor RB, Haller D. Interleukin-10 blocked endoplasmic reticulum stress in intestinal epithelial cells: impact on chronic inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(1):190–207. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oh-hashi K, Koga H, Ikeda S, Shimada K, Hirata Y, Kiuchi K. CRELD2 is a novel endoplasmic reticulum stress-inducible gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;387(3):504–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Belmont PG, Chen WJ, San Pedro MN, Thuerauf DJ, Gellings Lowe N, Gude N, Hilton B, Wolkowicz R, Sussman MA, Glembotski CC. Roles for endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation and the novel endoplasmic reticulum stress response gene Derlin-3 in the ischemic heart. Circ Res. 2010;106(2):307–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.203901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tewari N, Kalkunte S, Murray DW, Sharma S. The water channel aquaporin 1 is a novel molecular target of polychlorinated biphenyls for in utero anomalies. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(22):15224–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808892200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gunnett CA, Heistad DD, Berg DJ, Faraci FM. IL-10 deficiency increases superoxide and endothelial dysfunction during inflammation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279(4):H1555–62. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.4.H1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Didion SP, Kinzenbaw DA, Schrader LI, Chu Y, Faraci FM. Endogenous interleukin-10 inhibits angiotensin II-induced vascular dysfunction. Hypertension. 2009;54(3):619–24. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.137158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kinzenbaw DA, Chu Y, Peña Silva RA, Didion SP, Faraci FM. Interleukin-10 protects against aging-induced endothelial dysfunction. Physiol Rep. 2013;1(6):e00149. doi: 10.1002/phy2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eto N, Miyagishi M, Inagi R, Fujita T, Nangaku M. Mitogen-activated protein 3 kinase 6 mediates angiogenic and tumorigenic effects via vascular endothelial growth factor expression. Am J Pathol. 2009;174(4):1553–63. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sumida T, Naito AT, Nomura S, Nakagawa A, Higo T, Hasimoto A, Okada K, Sakai T, Ito M, Yamaguchi T, Oka T, Akazawa H, et al. Complement C1q-induced activation of β-catenin signalling causes hypertensive arterial remodelling. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6241. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Biswas S, Adhikari A, Chattopadhyay JC, Ghosh SK. Histological changes of placentas associated with intra-uterine growth restriction of fetuses: a case control study. Nepal Med Coll J. 2012;14(1):18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Sahan N, Grynspan D, von Dadelszen P, Gruslin A. Maternal floor infarction: management of an underrecognized pathology. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40(1):293–6. doi: 10.1111/jog.12159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coan PM, Vaughan OR, Sekita Y, Finn SL, Burton GJ, Constancia M, Fowden AL. Adaptations in placental phenotype support fetal growth during undernutrition of pregnant mice. J Physiol. 2010;588(Pt 3):527–38. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.181214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dilworth MR, Sibley CP. Review: transport across the placenta of mice and women. Placenta. 2013;34(Suppl):S34–9. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clark DA. The use and misuse of animal analog models of human pregnancy disorders. J Reprod Immunol. 2014;103:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ganguly A, Collis L, Devaskar SU. Placental glucose and amino acid transport in calorie-restricted wild-type and Glut3 null heterozygous mice. Endocrinology. 2012;153(8):3995–4007. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]