Abstract

Our objective was to identify agency-level factors that increase collaborative relationships between agencies that serve children with complex chronic conditions (CCC). We hypothesized that an agency will collaborate with more partners in the network if the agency had a coordinator and participated in a community coalition. We surveyed representatives of 63 agencies that serve children with CCC in Forsyth County, North Carolina about their agencies’ collaborations with other agencies. We used social network analytical methods and exponential random graph analysis to identify factors associated with collaboration among agencies. The unit of analysis was the collaborative tie (n = 3,658) between agencies in the network. Agencies participating in a community coalition were 1.5 times more likely to report collaboration than agencies that did not participate in a coalition. Presence of a coordinator in an agency was not associated with the number of collaborative relationships. Agencies in existence for a longer duration (≥11 vs. ≤10 years; adjusted odds ratio (aOR): 2.1) and those with a higher proportion of CCC clientele (aOR: 2.1 and 1.6 for 11–30 % and ≥31 % compared to ≤10 %) had greater collaboration. Care coordination agencies and pediatric practices reported more collaborative relationships than subspecialty clinics, home-health agencies, durable medical equipment companies, educational programs and family-support services. Collaborative relationships between agencies that serve children with CCC are increased by coalition participation, longer existence and higher CCC clientele. Future studies should evaluate whether interventions to improve collaborations among agencies will improve clinical outcomes of children with CCC.

Keywords: Children, Complex chronic conditions, Network analysis, Collaboration, Health services

Introduction

An estimated 9.3 million children in the United States (13–18 % of all children) have special health care needs [1, 2]. A sub-group of children with special health care needs have greater medical complexity [3] and are referred to as children with complex chronic conditions [4], medically complex children [5], children with medical complexity [6] or medically fragile children [7]. We use the term children with complex chronic conditions (CCC) to describe these children. Children with CCC account for substantial health-care utilization among children [7–10].

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), in a recent White Paper, described the concept of a “medical neighborhood” [11]. The medical neighborhood includes, in addition to the patient’s medical home, all specialists and agencies involved in the health care of an individual. The AHRQ recommends a high-functioning medical neighborhood to be critical to our health-care system. The framework of medical neighborhood is particularly relevant to the system of care of children with CCC, as these children receive care from multiple providers through various agencies.

Developing systems of coordinated care for children with special needs in communities is a Healthy People 2020 Objective [12]. However, very little information exists on how agencies within this system collaborate with one another to provide care for this population.

To study the collaborative relationships that exist between agencies that serve children with CCC we used Social Network Analysis (SNA), a method that has been used to study relationships between individuals and organizations [13–15]. SNA is a structural approach to studying linkages between a set of constituents of a network [16]. SNA is particularly suitable for understanding complex systems that cannot be evaluated from the properties of individual parts of the system [13, 14].

We used SNA methodology to (1) describe the network of collaboration among agencies that serve children with CCC; and (2) identify agency-level factors that increase collaborative relationships with other agencies in the network. Specifically, we wanted to evaluate whether presence of a coordinator in an agency and participation in community coalitions were associated with increased collaboration with other agencies. Prior studies evaluating models of care coordination have used a designated person to deliver comprehensive care [17, 18]. Community coalition is another approach to improve or change health systems [19]. Pediatric coalitions have been established in some communities to address issues unique to children with CCC [20]. We hypothesize that the presence of a coordinator within an agency and agency’s participation in a community coalition will increase an agency’s collaborative relationships.

Methods

The Institutional Review Board of Wake Forest University Health Sciences approved this study. The methodology is described in detail in a previous study (article in press) [21]. This study was conducted in Forsyth County located in central North Carolina. In 2010, the population of Forsyth County was 350,670 and the median household income was $47,000 [22]. Winston-Salem is the largest city in Forsyth County accounting for two-thirds of its population. Racial and ethnic minorities constitute 38 % of the population of Forsyth County.

Defining the Network

The network in this study consists of agencies serving children with CCC. The first step in SNA methodology is to identify all potential actors within the network. In this study, agencies are the actors. We used multiple steps to identify agencies (actors) as described previously (manuscript in press) [21]. The process of defining the network is described in Table 1. Briefly, we generated a preliminary list of agencies in Forsyth County that serve children with CCC from multiple existing resources. Next, we conducted a focus group with members of a community coalition, who were representatives of agencies serving children with CCC. Third, we interviewed 8 social workers in the academic medical center and 2 social workers in the community, all of whom work primarily with children with CCC. Finally, only agencies that met all the three of the following criteria were included: (1) serve all of Forsyth County, (2) focus on children with CCC and/or their families, and (3) provide ongoing care to children with CCC and/or their families. Agencies were considered to focus on children with CCC if they had special services in place for children with CCC, their needs were addressed as part of the agencies’ programmatic goals, or if they made up a large portion of the agency’s clientele (10 % or more).

Table 1.

Process of defining the network boundary

| Steps/actions | Resulting changes to agency list | Characteristics of agencies in the list | Agencies in boundary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creation of preliminary list | 17 categories of agencies 44 provide medical care 11 unclassified |

133 | |

| Focus group conducted | 6 agencies added 43 agencies removed |

16 categories of agencies 43 provide medical care 14 unclassified |

139 |

| Social workers interviewed | 53 agencies added | 16 categories of agencies 48 provide medical care 15 unclassified |

192 |

| Inclusion rules applied | 5 agencies added 126 agencies removed |

6 categories of agencies | 71 |

| List finalized | 8 agencies removed | 6 categories of agencies | 63 |

Keeping with the convention used in prior studies, different programs within a large organization were treated as separate agencies if the programs provided a distinct set of services using non-overlapping staff [14, 23]. Of the 63 agencies in the final list, 28 (44 %) were subspecialty clinics of the children’s hospital, 7 (11 %) were nursing agencies, 3 (5 %) were Durable Medical Equipment (DME) companies, 6 (10 %) were educational agencies, 5 (8 %) were care coordination programs, 4 (6 %) were family support services, and 10 (16 %) were pediatric practices. Care coordination agencies included a hospital-based program for children with CCC; an early-intervention services provider; two Medicaid waiver programs for children with CCC; and care coordination programs of the local health department and a Medicaid managed care program. The agencies that provided family support services offered a variety of services and served as a resource for families of children with cancer; special needs; sickle cell and hemophilia; and heart diseases. Nursing agencies included 4 agencies that provide skilled nursing, one longterm care facility and one hospice agency.

Survey

The study participants were key informants (agency representatives) in the agencies. We identified 96 Key Informants representing 63 agencies. We conducted a survey of all key informants in October 2010 using Network Genie, an online data-collection tool developed specifically for social network data [24]. The link to the survey was emailed to participants. A reminder was sent to non-responders 2 weeks after the first survey. A second reminder was sent to non-responders 5 weeks after the first reminder. Participants received $25 incentives for participating in the study.

On the survey, we defined children with complex chronic conditions as children who are medically fragile, dependent on technology, or have a life-limiting condition. The survey questions are presented in “Appendix”. The survey had one general question inquiring about collaboration with other agencies and 4 follow-up questions about the nature of the relationships that did exist (serving as a resource, receiving resource, making referrals and receiving referrals). We also inquired about the agency’s interest in collaborating with other agencies in the future. Respondents also provided information about their agency, including : agency type, duration of existence, number of children served each week, number of staff members in the agency providing direct care to children, presence of a coordinator in the agency and the proportion of children with CCC served by the agency.

Some agencies had multiple respondents (key informants). In determining whether the agency had collaborative relationships with another agency, we concluded that a relationship was in place if either informant reported it [14]. For questions about duration of existence, number of staff, number of children served and proportion of clientele that are children with CCC, we chose the median value among the multiple respondents. For questions about presence of a coordinator and participation in coalition, responses were combined such that an affirmative response from any one of the respondents was considered to be an affirmative response.

Variables

For the current study, we used only the general network question that inquired about any type of collaboration with other agencies:

In the past year, with which of the following agencies has your agency collaborated in providing services for children with complex chronic conditions?

We defined collaboration, to participants, as any relationship that involves exchanging information, sharing resources, and/or coordinating services for the benefit of children with complex chronic conditions. The dependent variable (described below) was the collaborative tie derived from this network question. The different agency attributes served as independent variables in the analysis. These variables were categorized as follows: duration of existence (≤10 or ≥11 years); number of staff (≤5, 6–30 and ≥31); proportion of clientele that are CCC (≤10, 11–30, ≥31); participation in coalition (yes, no or missing) and presence of a coordinator (yes or no). The coordinator variable was derived from the question that inquired whether there was a designated person in the agency whose job was to collaborate with other agencies on behalf of clients in the agency. One person who responded as ‘unsure’ for the question about presence of coordinator was categorized as ‘no’.

Visual Representation of the Network

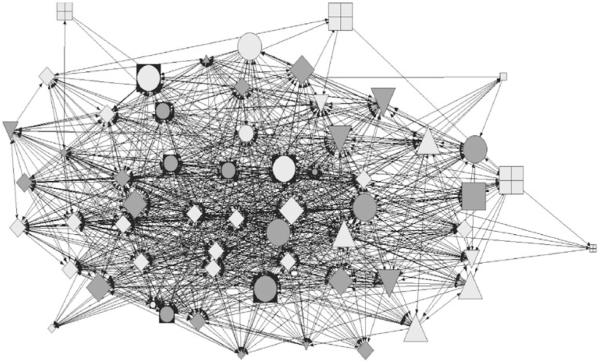

We constructed a visual representation of the network (Fig. 1) to depict the collaborative relationships between organizations (collaboration network). This is a standard procedure when analyzing network data [25]. The individual agencies in the network are called ‘actors’ (depicted in different shapes in Fig. 1). The connection from an actor to other actors in the network is called the arc (represented as arrows). The direction of the arrows represents the direction of the arc. In our study, agencies are the actors and the reported collaborative relationship of an agency to other agencies in the network is the arc. A tie is any relationship between actors in the network—either to or from an actor to other actors in the network.

Fig. 1.

Collaboration network of agencies serving children with CCC. Circle care-coordination agencies, diamond subspecialty clinics, inverted triangle nursing agencies, square with plus family-support services, triangle educational programs opened square DME companies, square with circle at center pediatric practices. Largest size coalition participation “yes”; medium size coalition participation “no”; smallest size coalition participation “missing”. Dark shade presence of coordinator; light shade no coordinator in agency

Measures

The unit of analysis is the collaborative tie between two agencies in the network. In a network of 63 agencies, there are a possible 3,906 (63 × 62) ties in the network. Since we had response from 59 of the 63 agencies, we had information about 3,658 (59 × 62) ties in this network.

For descriptive statistics of the network, the density and centralization of the network were calculated. Density is the proportion of actual ties between actors to the total number of possible ties. A higher density indicates greater relationship between agencies. Centralization is the extent to which the ties are limited to a few actors; thus a lower centralization score indicates a broader distribution of ties. Out-degree centrality of the network was the dependent variable in this study. Out-degree centrality is the connectivity of actors within the network measured by the number of reported arcs from an actor to other actors in the network. Out-degree centrality is expressed as a whole number. We evaluated the association between each one of the agency attributes described above (independent variables) and out-degree centrality (dependent variable) of the network.

Data Analysis

For description of agency attributes, we used Stata Intercooled Version 10. Since observations in a network data are not independent, traditional statistical analyses are not appropriate for network data [26]. Hence, we used statistical analyses designed for SNA data. For univariate network analysis and visual representation, we used UCINET 6 and the NetDraw option [27]. For multivariate regression analyses we used Exponential Random Graph Modeling (ERGM), implemented using the program Statnet as described before [28, 29]. We calculated adjusted Odds Ratios (and 95 % Confidence Interval) for out-degree centrality for the independent variables in the model. A p value of <0.05 defined statistical significance.

Results

Of the 96 eligible participants, 80 (83 %) responded to the survey. Seventy-seven (80 %) completed the entire survey. Of the 63 agencies, we received responses from at least one key informant in 59 agencies (94 %). Agencies that did not respond include one each of subspecialty clinic, pediatric practice, DME company and educational program.

Agency Characteristics

The characteristics of the agencies are presented in Table 2. The most common type of agency was a subspecialty clinic in the children’s hospital. Majority of agencies had existed for 11 or more years (76 %). Twenty-six (44 %) agencies had 5 or less staff providing direct care to children. For 42 % of the agencies, children with CCC constituted more than 30 % of their clientele.

Table 2.

Characteristics of agencies (n = 59)

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Service typea | |

| Care coordination | 5 (8 %) |

| Pediatric practice | 10 (16 %) |

| Subspecialty clinic | 28 (44 %) |

| Nursing agency | 7 (11 %) |

| DME companies | 3 (5 %) |

| Educational programs | 6 (10 %) |

| Family-support services | 4 (6 %) |

| Duration of existence (years) | |

| ≤10 | 14 (24 %) |

| ≥11 | 45 (76 %) |

| Number of staff | |

| ≤5 | 26 (44 %) |

| 6–30 | 22 (37 %) |

| ≥31 | 11 (19%) |

| Clientele are children with CCC (%) | |

| ≤10 | 24 (41 %) |

| 11–30 | 10 (17 %) |

| ≥31 | 25 (42 %) |

| Agency has a coordinator | 27 (46 %) |

| Coalition participation | |

| Yes | 28 (44 %) |

| No | 22 (35 %) |

| Missing | 9 (21 %) |

n = 63

Less than half of the agencies had a designated coordinator. The proportions of agencies having a designated coordinator were as follows: nursing agencies 71 %; pediatric practices 67 %; care coordination agencies 60 %; subspecialty clinics 41 %; DME companies 20 %; educational programs 20 %; and family-support services 0 %. Forty-four percent of the agencies participated in at least one community coalition. Agencies’ participation in a community coalition were as follows: care coordination programs 80 %; educational programs 80 %; family-support services 50 %; DME companies 50 %; nursing agency 43 %; pediatric practice 33 %; and subspecialty clinics 19 %.

Network Characteristics

Figure 1 describes the network of collaboration among all agencies participating in the study. This figure shows that the care coordination agencies and some pediatric practices are in the center of the network suggesting greater collaboration whereas family-support services, nursing agencies and DME companies are in the periphery suggesting less collaboration.

There were 1,380 ties in this network out of a possible 3,658 ties resulting in a network density of 38 %. The mean out-degree centrality was 22 (average number of collaborative relationships for agencies in the network). The centralization score for the network was 53 % for out-degree centrality, suggesting that a few agencies account for much of the network’s collaboration.

Association of Agency Attributes and Out-Degree Collaborative Relationship

The results of ERGM analysis of out-degree centrality with agency attributes are presented in Table 3. Contrary to our hypothesis, presence of a coordinator in an agency was not associated with greater collaboration with other agencies in the network compared to those that did not have a coordinator (aOR: 0.98; 95 % CI 0.83–1.15). Participation in a community coalition was however associated with greater collaboration (aOR 1.5; 95 % CI 1.22–1.85); agencies that did not respond to this question were less likely to collaborate than that did not participate in a coalition.

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratios of out-degree collaborations by agency characteristics

| Agency characteristic | Out-degree | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| aOR (95 % CI) | p | |

| Coordinator | ||

| No | Reference | |

| Yes | 0.98 (0.83, 1.15) | 0.79 |

| Coalition participation | ||

| No | Reference | |

| Yes | 1.5 (1.22, 1.85) | 0.0001 |

| Missing | 0.64 (0.49, 0.82) | 0.0005 |

| Service type | ||

| Care coordination | Reference | |

| Pediatric practice | 1.37 (0.95, 1.98) | 0.09 |

| Subspecialty clinic | 0.53 (0.39, 0.73) | <0.0001 |

| Nursing agency | 0.22 (0.15, 0.32) | <0.0001 |

| DME companies | 0.2 (0.11, 0.37) | <0.0001 |

| Educational programs | 0.34 (0.23, 0.51) | <0.0001 |

| Family-support services | 0.09 (0.05, 0.15) | <0.0001 |

| Duration of existence (years) | ||

| ≤10 | Reference | |

| ≥11 | 2.1 (1.66, 2.67) | <0.0001 |

| Number of staff | ||

| ≤5 | Reference | |

| 6–30 | 0.67 (0.55, 0.82) | <0.0001 |

| ≥31 | 1.09 (0.82, 1.03) | 0.56 |

| Clientele are children with CCC (%) | ||

| ≤10 | Reference | |

| 11–30 | 2.11 (1.63, 2.73) | <0.0001 |

| ≥31 | 1.63 (1.3, 2.03) | <0.0001 |

aOR adjusted odds ratio

CI confidence interval

Subspecialty clinics, educational programs, nursing agencies, DME companies and family-support programs were less likely than care-coordination agencies to report collaboration with other agencies in the network. There was no significant difference between primary-care providers and care coordination agencies in the number of collaborations. Greater duration of existence and higher proportion of CCC clientele were associated with greater collaboration compared to their counterparts. Higher number of staff members in an agency was associated with less collaboration.

Discussion

Prior research has shown that care coordinators in an agency help improve patient-level outcomes for children with special health care needs [17, 18]. Thus, we hypothesized that the presence of a coordinator in an agency would increase collaboration with other agencies in the medical neighborhood of children with CCC. However, we found that agencies with a coordinator did not have more collaborative relationships than those without a coordinator. One possible explanation for the null effect observed is that the coordinators employed by various agencies in the study are not all performing similar forms of coordination activities. For example, some might work directly with other agencies, while other coordinators might operate in more of a behind-the-scenes mode by connecting families to agencies indirectly. It should be noted that even though having a coordinator inside the agency did not predict the amount of collaboration, we did find that care coordination agencies reported high levels of collaboration. Future studies should determine what specific care coordination task helps enhance collaborative relationships between agencies.

Community coalitions, defined as a group of organizations and individuals with the stake in the issue working together to achieve a common goal [30], have been used to improve health status or change health systems [19]. Our study provides evidence for the benefit of community coalitions in increasing the likelihood of collaboration in the care of children with CCC. This association between coalition participation and increased collaborative relationship should be evaluated in longitudinal studies.

Care coordination agencies and primary-care pediatric practices were more likely to report collaboration than subspecialty clinics, nursing agencies, DME companies, educational programs and family-support services. This is consistent with the medical home model in which primary-care practices serve as the hub for medical care of children with CCC [31]. Increased number of years of existence and number of children with CCC were also independently associated with greater collaborations with other agencies in the network. This suggests that for collaborations to be established, ongoing relationships and opportunities for collaboration are necessary. Interestingly, the number of staff decreased the odds of collaboration. It is possible that smaller agencies have greater need for assistance and hence seek out collaborations with other agencies.

We have applied a novel tool, Social Network Analysis (SNA), to understand relationships between agencies serving children with CCC. It is an established methodology in the fields of education and business to study relationships between organizations [13–15], but has only recently begun to gain interest among health services researchers. Prior studies have used SNA to study delivery systems in HIV service delivery systems [14] and in longterm care facilities [32]. Our study shows the value of this methodology for pediatric health-services researchers.

Limitations

Our study is limited to a single county in North Carolina and hence the results may not be generalizable to the medical neighborhood of children with CCC in other regions. Although we used multiple approaches to identify agencies in the network we studied, we cannot be certain that we identified all agencies. On the other hand, the response rate was high among the agencies we surveyed, minimizing selection bias. Another possible limitation is that we relied on agencies’ self-reporting of collaborative relationships and attributes of their agency, such as the presence of coordinator. We did not use parent/caregiver perspective on collaboration between agencies. Finally, because of the cross-sectional design of our study, we are unable to establish causality in the associations we have observed.

Conclusions

Using network analytical methods, we have identified agencies’ participation in community coalitions, longer duration of existence and higher CCC clientele to be associated with collaboration with other agencies serving children with CCC at a community level. Collaborative relationships are strengthened by these factors that provide opportunities for collaboration. Future studies should examine whether interventions to increase collaborations between agencies can result in improvement in patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript was provided by NICHD R21HD061793; PI: Nageswaran.

Appendix. Survey Questions

In the past year, with which of the following agencies has your agency collaborated in providing services for children with complex chronic conditions? By collaboration, we mean any relationship that involves exchanging information, sharing resources, and/or coordinating services for the benefit of children with complex chronic conditions. [Select all that apply. Please do not select your own agency.] [Main Question—List of all actors in the network]

Do the following agencies serve as a resource for your agency in your role as a service provider to children with complex chronic conditions? “Serving as a resource” might include: providing care-related information, offering advice or consultation on how to serve a client or family etc. [Matrix of agencies identified in Q1 with “Yes” and “No” options]

Does your agency serve as a resource to the following agencies as they provide services to children with complex-chronic conditions? [Matrix of agencies identified in Q1 with “Yes” and “No” options]

Has your agency referred children with complex chronic conditions to the following agencies in the past year? [Matrix of agencies identified in Q1 with “Yes” and “No” options]

Has your agency received referral about children with complex chronic conditions from the following agencies in the past year? [Matrix of agencies identified in Q1 with “Yes” and “No” options]

With which of these agencies would you like to collaborate more in order to effectively provide services for children with complex chronic conditions? [List of all actors in the network]

What is your title in your agency? [Text Box]

Please select the item that best describes your agency: [Drop down list: “private for-profit”; “private non-profit”; “government”; “other”]

How long has your agency been serving children? [Drop down list: less than 5 years, 6–10 years, 11–20 years, more than 20 years]

On average, how many children does your agency serve each week? [Drop down list: <10, 11–20, 21–50, 51–100, >100]

How many staff members are directly involved in providing services to children? [Drop down menu: <5, 6–10, 11–20, 21–30, more than 30]

Is there a designated person in your agency whose job it is to collaborate with other agencies on behalf of clients in your agency? [Drop down list: “yes” “no” “unsure”]

About what percentage of clients in your agency are children with complex chronic conditions? We define children with complex chronic conditions as children who are medically fragile, dependent on technology, or have a life-limiting condition. [Drop down list: <1 %; 1–10 %; 11–20 %; 21–30 %; and >31 %]

- 14. In which of the following community coalitions do representatives from your agency participate? Select all that apply.

- (a) Pediatric Community Alliance (PCA)

- (b) Local Collaborative Team

- (c) Local Interagency Coordinating Council (LICC)

- (d) Forsyth Adolescent Health Coalition

- (e) Forsyth County Healthy Carolinians Coalition

- (f) Infant Mortality Reduction Coalition

- (g) Lead Poisoning Prevention Coalition

- (h) School Health Alliance

- (i) Forsyth Futures

- (j) Safe Kids Coalition

- (k) Other coalitions not listed here

- (l) None

- (m) Don’t know

Contributor Information

Savithri Nageswaran, Email: snageswa@wakehealth.edu, Department of Pediatrics, Wake Forest School of Medicine, 1 Medical Center Blvd, Winston-Salem, NC 27157, USA; Social Sciences and Health Policy, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA.

Shannon L. Golden, Department of Pediatrics, Wake Forest School of Medicine, 1 Medical Center Blvd, Winston-Salem, NC 27157, USA

Douglas Easterling, Social Sciences and Health Policy, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA.

T. Michael O’Shea, Department of Pediatrics, Wake Forest School of Medicine, 1 Medical Center Blvd, Winston-Salem, NC 27157, USA; Social Sciences and Health Policy, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA.

William B. Hansen, Tanglewood Research Inc., Greensboro, NC, USA

Edward H. Ip, Social Sciences and Health Policy, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA Biostatistical Sciences, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA.

References

- 1.McPherson M, Weissman G, Strickland BB, et al. Implementing community-based systems of services for children and youths with special health care needs: How well are we doing? Pediatrics. 2004;113(5 Suppl):1538–1544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative National Survey of Children’s Health, Data Resource Center on Child and Adolescent Health website. 2005 www.nschdata.org. Accessed 05 July 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuo DZ, Cohen E, Agrawal R, et al. A national profile of caregiver challenges among more medically complex children with special health care needs. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165(11):1020–1026. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.172. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: A population-based study of Washington State, 1980–1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1):205–209. Pt 2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srivastava R, Stone BL, Murphy NA. Hospitalist care of the medically complex child. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2005;52(4):1165–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2005.03.007. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen E, Kuo DZ, Agrawal R, et al. Children with medical complexity: An emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):529–538. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buescher PA, Whitmire JT, Brunssen S, et al. Children who are medically fragile in North Carolina: Using Medicaid data to estimate prevalence and medical care costs in 2004. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2006;10(5):461–466. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;305(7):682–690. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon TD, Berry J, Feudtner C, et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):647–655. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3266. doi:10.1542/peds. 2009-3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neff JM, Sharp VL, Muldoon J, et al. Profile of medical charges for children by health status group and severity level in a Washington State Health Plan. Health Series Research. 2004;39(1):73–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00216.x. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00216.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor E, Lake T, Nysenbaum J, Peterson G, Myers D. Coordinated care in the medical neighborhood: Critical components and available mechanisms. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2011. White paper (prepared by mathematica policy research under contract no. HHSA290200 900019I TO2). AHRQ Publication No. 11-0064. [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Available at [Specific URL]. Accessed 26 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott J, Tallia A, Crosson JC, et al. Social network analysis as an analytic tool for interaction patterns in primary care practices. Annals of Family Medicine. 2005;3(5):443–448. doi: 10.1370/afm.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwait J, Valente TW, Celentano DD. Interor-ganizational relationships among HIV/AIDS service organizations in Baltimore: A network analysis. Journal of Urban Health. 2001;78(3):468–487. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, et al. Factors affecting influential discussions among physicians: A social network analysis of a primary care practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22(6):794–798. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0190-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawe P, Webster C, Shiell A. A glossary of terms for navigating the field of social network analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2004;58(12):971–975. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.014530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farmer JE, Clark MJ, Sherman A, et al. Comprehensive primary care for children with special health care needs in rural areas. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):649–656. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palfrey JS, Sofis LA, Davidson EJ, et al. The pediatric alliance for coordinated care: Evaluation of a medical home model. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5 Suppl):1507–1516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreuter MW, Lezin NA, Young LA. Evaluating community-based collaborative mechanisms: Implications for practitioners. Health Promotion Practice. 2000;1(1):47–61. [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization . Caring for kids: How to Develop a Home-Based Support Program for Children and Adolescents with Life-Threatening Conditions. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization; Alexandria, VA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nageswaran S, Ip E, Golden SL, et al. Inter-agency collaboraiton in the care of children with complex chronic conditions. Academic Pediatrics. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.U.S. Census Bureau State and County QuickFacts. Data derived from Population Estimates, American Community Survey, Census of Population and Housing, State and County Housing Unit Estimates, County Business Patterns, Nonemployer Statistics, Economic Census, Survey of Business Owners, Building Permits, Consolidated Federal Funds Report. 2010 http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html. Accessed 26 April 2012.

- 23.Friedman SR, Reynolds J, Quan MA, et al. Measuring changes in interagency collaboration: An examination of the Bridgeport safe start initiative. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2007;30(3):294–306. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Network Genie Tanglewood research incorporated. 2011 https://secure.networkgenie.com/

- 25.Luke DA, Harris JK. Network analysis in public health: History, methods, and applications. Annual Review of Public Health. 2007;28:69–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanneman R, Riddle M. Inroduction to social network methods. University of California, Riverside; Riverside, California: 2005. http://www.faculty.ucr.edu/*hanneman/nettext/. Accessed 25 August 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.UCINET 6: Social Network Software Analytic technologies. 2008 http://www.analytictech.com/ucinet/ucinet.htm. Accessed 25 August 2008.

- 28.Goodreau SM, Handcock M, Hunter DR, Butts CT, Morris M. A statnet tutorial. Journal of Statistical Software. 2008;24(8):1–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunter DR, Handcock M, Butts CT, Goodreau SM, Morris M. ERGM: A package to fit, simulate and diagnose exponential-family models for networks. Journal of Statistical Software. 2008;24(3):1–29. doi: 10.18637/jss.v024.i03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Granner ML, Sharpe PA. Evaluating community coalition characteristics and functioning: A summary of measurement tools. Health Education Research. 2004;19(5):514–532. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Care coordination in the medical home Integrating health and related systems of care for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2005;116(5):1238–1244. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cott C. “We decide, you carry it out”: A social network analysis of multidisciplinary long-term care teams. Social Science and Medicine. 1997;45(9):1411–1421. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]