Abstract

Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) is a distinct subtype of extranodal lymphoma with aggressive clinical course and poor outcome. As increased IL‐10/IL‐6 ratio is recognized in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of PCNSL patients, we hypothesized that PCNSL might originate from a population of B cells with high IL‐10‐producing capacity, an equivalent of “regulatory B cells” in mice. We intended in this study to clarify whether Tim‐1, a molecule known as a marker for regulatory B cells in mice, is expressed in PCNSL. By immunohistochemical analysis, Tim‐1 was shown to be positive in as high as 54.2% of PCNSL (26 of 58 samples), while it was positive in 19.1% of systemic diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma (DLBCL) samples (17 of 89 samples; P < 0.001). Tim‐1 expression positively correlated with IL‐10 expression in PCNSL (Cramer's V = 0.55, P < 0.001), and forced expression of Tim‐1 in a PCNSL cell line resulted in increased IL‐10 secretion, suggesting that Tim‐1 is functionally linked with IL‐10 production in PCNSL. Moreover, soluble Tim‐1 was detectable in the CSF of PCNSL patients, and was suggested to parallel disease activity. In summary, PCNSL is characterized by frequent Tim‐1 expression, and its soluble form in CSF may become a useful biomarker for PCNSL.

Keywords: Biomarker, central nervous system, diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma, immunohistochemistry, Tim‐1

Introduction

Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) is an uncommon form of extranodal non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma that arises within the central nervous system (CNS), most cases of which demonstrate diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma (DLBCL) histology 1. Although the etiology for the development of lymphoma in this extranodal site remains unclear, PCNSL patients are known to be characterized by high IL‐10/IL‐6 ratio in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and it may be speculated that PCNSL is derived from B cells with IL‐10‐producing capacity.

In mouse models of multiple sclerosis (experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, EAE) and cerebral infarction, a population of IL‐10‐producing B cells, named regulatory B cells, has been shown to have a function to migrate to the CNS and suppress inflammation 2, 3, 4. These regulatory B cells are reported to express a cell surface molecule T‐cell immunoglobulin domain and mucin domain protein 1 (Tim‐1) at a high frequency 5.

Tim‐1 is a type I cell surface glycoprotein that is expressed on various immune cells, such as activated T cells, B cells, natural killer T (NKT) cells, and dendritic cells, and regulates diverse immune responses 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12. It is also known to be induced on tubular epithelial cells following kidney injury 13, and it is then cleaved at a membrane proximal point and the extracellular domain of the protein is released into the urine 14, 15, 16. In B cells, Tim‐1 is shown to be expressed by a large majority of IL‐10‐expressing population 5. Regulatory B cells with defective Tim‐1 mutation have a profound defect in IL‐10 production, suggesting that Tim‐1 plays a pivotal role in their IL‐10 production 17.

We hypothesized that PCNSL may originate from such B cells that have a physiological role in producing IL‐10 to suppress unfavorable inflammation in the CNS. In this study, we found that Tim‐1 was detected in more than half of the PCNSL samples by immunohistochemistry, and Tim‐1 was also detectable in soluble form in the CSF of PCNSL patients with active disease. Our findings suggest that PCNSL is characterized by frequent Tim‐1 expression, and detection of soluble Tim‐1 in CSF may be useful for the diagnosis and evaluating the disease activity of PCNSL.

Materials and Methods

Clinical samples, immunohistochemistry, and ELISA

For immunohistochemical analysis, formalin‐fixed, paraffin‐embedded samples of 48 PCNSL (median age 63; age range 16–86 years) and 89 systemic DLBCL patients (median age 67; age range 22–86 years) diagnosed at Kyoto University Hospital, Nagasaki University Hospital, Kobe Central Citizen Hospital, and Tenri Hospital were used. All PCNSL samples were obtained from immunocompetent patients at first diagnosis, and were of DLBCL histology. They were stained with anti‐Tim‐1 antibody (MAB 1750; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), anti‐IL‐10 antibody (AF‐217; R&D Systems), anti‐CD3 antibody (2GV6; Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ), and anti‐CD20 antibody (L26; DAKO, Carpinteria, CA). Cut‐off values of Tim‐1 and IL‐10 positivity were set as 30%, according to the criteria that are commonly applied to the IHC analysis of lymphoma 18. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 11 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). The Chi‐square test, Mann–Whitney U‐test, t‐test, and paired t‐test were used for comparison between two groups. Fluorescent double staining was performed by labeling anti‐Tim‐1 antibody with FITC‐conjugated donkey anti‐mouse antibody (ab98770; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and anti‐IL‐10 antibody with rabbit anti‐goat antibody (E0466; DAKO, Carpinteria, CA), and Alexa555‐conjugated donkey anti‐rabbit antibody (ab150070; Abcam). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (H‐1200; Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA).

CSF samples were collected from lymphoma patients after obtaining written informed consent, and were centrifuged at 2000g for 10 min at 4°C and stored at −80°C until analysis. Soluble Tim‐1 levels of the CSF samples were analyzed by ELISA using Human Tim‐1/KIM‐1/HAVCR Duoset (R&D Systems) following the manufacturer's instructions. These clinical samples were obtained and used under the approval of the Institutional Review Board of each institute, and performed in accordance with the ethical standards of an institutional research committee and the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Gene expression analysis

The expression levels of TIM‐1 and IL‐10 genes were compared using the previously published datasets available in the NCBI GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). We picked up GEO series data and obtained the cell intensity files from the database. The CEL files were imported into the R software package (ver. 3.1.1., Free Software Foundation, Boston, MA), and the probe‐level data were converted into normalized expression profiles using the Affy package 19. The expression levels of each gene were normalized using ACTB.

Cell lines and immunoblot analysis

A PCNSL cell line, TK (JCRB1206), was obtained from JCRB Cell Bank (Tokyo, Japan). A Burkitt lymphoma cell line, Raji, a mantle cell lymphoma cell line, Granta 519, and a mouse fibroblast cell line, L cells, were as described elsewhere 20, 21, 22. These cell lines were cultured in RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 10% (or 20% for TK cells) heat‐inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 μg/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2 mmol/L L‐glutamine. A human embryonic kidney cell line, 293T, was cultured in DMEM containing 10% FCS, penicillin, streptomycin, and L‐glutamine.

For immunoblot analysis, the cells were lysed in lysis buffer (25 mmol/L HEPES [pH 7.4], 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1.0% Triton X‐100, 10% glycerol, and protease inhibitor cocktail). Total cell lysates and cell supernatants of the culture medium were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to Immobilon‐P polyvinylidene difluoride transfer membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The membranes were immunoblotted with anti‐Tim‐1 antibody (clone 219211; R&D Systems) or anti‐FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The membranes were subsequently incubated with horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated anti‐mouse secondary antibody, and immunoreactive proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence reaction using SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL).

TIM‐1 transfection assay

Human TIM‐1 transcript was PCR amplified from cDNA of the lung adenocarcinoma cell line A549, which is known to express a high level of Tim‐1 23, and subcloned into pFLAG‐CMV‐5a expression vector (Sigma). The vector was transduced into 293T cells using X‐tremeGENE HP DNA Transfection Reagent (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Flag‐tagged Tim‐1 was also subcloned into a pCS‐CAG‐EGFP lentiviral vector, which was constructed by replacing the CD19 promoter of Eμmar‐L.CD19‐EGFP vector with CAG promoter 24, 25. The packaging plasmid pCAG‐HIVgp and the VSV‐G‐ and Rev‐expressing plasmids (pCMV‐VSV‐G‐RSV‐Rev) were kindly provided by Dr. H. Miyoshi, RIKEN Bioresource Center, Tsukuba, Japan. TIM‐1 expression vector was transfected into 293T cells with packaging plasmids, and viral supernatants were collected after 48 h, concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 20,000g for 2 h, and transduced in TK cells.

TIM‐1 or mock‐introduced 293T and TK cells were incubated for 12 h in a serum‐free medium, and the cells and supernatants were separately collected and analyzed for Tim‐1 protein expression by immunoblotting. For cell viability assay, TK cells were resuspended in RPMI‐1640 medium with 20% FCS at a concentration of 4 × 106/mL and seeded in a 96‐well plate. After 24 and 48 h of culture, IL‐10 production from TK cells introduced with mock or TIM‐1 expression vectors was analyzed by ELISA, using Human IL‐10 Duoset (R&D Systems) following the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were cultured with 15 μg/mL cisplatin or 20 μmol/L dexamethasone for 12 and 24 h, and cell apoptosis was evaluated by propidium iodide (PI) staining (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) and FACS analysis.

T‐cell proliferation and cytokine production analysis

TIM‐1‐expressing or mock vector was transfected into L cells, and supernatants were collected after culturing for 12 h. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells of three healthy donors were first separated from peripheral blood on a Ficoll‐paque density gradient (Sigma), and subsequently CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were collected using CD4 and CD8 MicroBeads and a magnetic‐activated cell sorting (MACS) system (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch‐Gladbach, Germany). CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were individually resuspended in the supernatants of L cells at a concentration of 1 × 106/mL, seeded in a 96‐well plate, and cultured under stimulation with anti‐CD3/CD28 beads (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). After 48 or 72 h of culture, cell numbers were counted and their supernatants were analyzed for cytokine production using the following ELISA kits: Human IL‐2 ELISA MAX Deluxe, Human IFN‐gamma ELISA MAX Standard, Human IL‐17A ELISA MAX Deluxe Set (Biolegend, CA), Human IL‐4 ELISA Set (Becton Dickinson, Mountainview, CA), and Human IL‐10 Duoset (R&D Systems).

Results

Increased expression of Tim‐1 in PCNSL

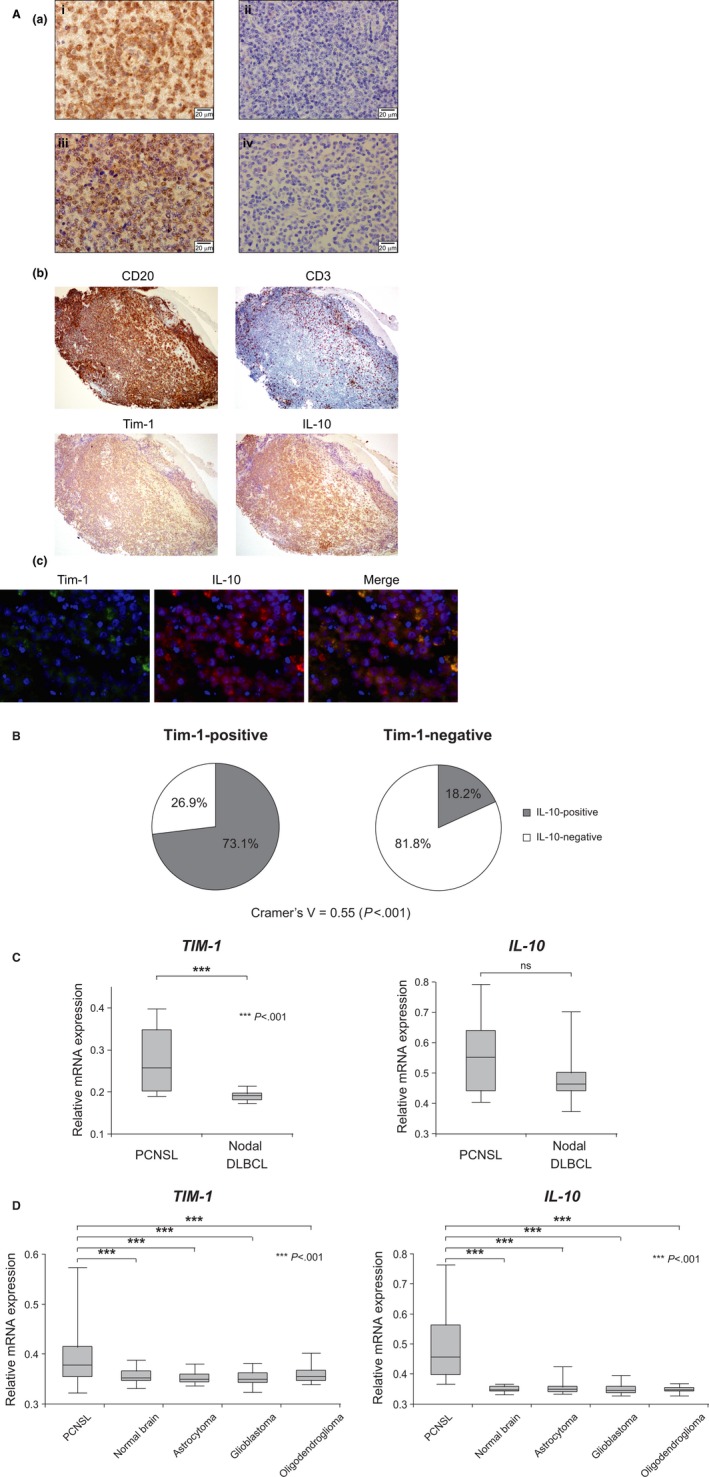

We first performed immunohistochemical staining of Tim‐1 and IL‐10 in 48 PCNSL and 89 systemic DLBCL samples (Fig. 1A, a). Tim‐1 and IL‐10 were positive in 17 (19.1%) and 14 (15.1%) of systemic DLBCL. In contrast, they were positive in 26 (54.2%) and 23 (47.9%) of PCNSL (vs systemic DLBCL, P < 0.001), and in most positive cases, both Tim‐1 and IL‐10 were stained in more than 80% of the tumor cells. Steroids had been administered before biopsy in 10 PCNSL patients, but they did not seem to affect much on Tim‐1 expression (Cramer's V = 0.15). Among systemic DLBCL, Tim‐1 was positive in 9 (26.5%) of 34 germinal center B‐cell like (GCB) and in 8 of 55 non‐GCB DLBCL evaluated by immunohistochemistry based on Hans' algorithm 18, suggesting that Tim‐1 expression was not significantly biased to either cell of origin (P = 0.178). Immunohistochemical staining of the serial sections and fluorescent double staining analysis indicated that Tim‐1 and IL‐10 were coexpressed in tumor B cells (Fig. 1A, b, c), and a moderate correlation was observed between their positivities (Cramer's V = 0.55, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1B). In contrast, their correlation was lower in systemic DLBCL (Cramer's V = 0.34, P < 0.005). There were five systemic DLBCL samples of the patients who subsequently developed CNS involvement, but all were negative for Tim‐1 while three were positive for IL‐10, and it was suggested that secondary CNS involvement of systemic DLBCL is not associated with Tim‐1 expression of the primary lesions.

Figure 1.

Increased expression of Tim‐1 in PCNSL. (A) (a) Representative immunohistochemical staining patterns of the (i) Tim‐1‐positive and (ii) ‐negative samples, and (iii) IL‐10‐positive and (iv) ‐negative samples (original magnification, ×600). (b) Representative results of the immunohistochemical staining of the serial sections of PCNSL samples (original magnification, ×100). (c) the fluorescent double staining for Tim‐1 and IL‐10 of PCNSL. (B) Pie charts showing IL‐10‐positive rates in the Tim‐1‐positive (left, n = 26) and ‐negative (right, n = 22) samples. (C) Comparison of the gene expression levels of TIM‐1 and IL‐10 between PCNSL (n = 9) and nodal DLBCL (n = 15) samples using microarray datasets available in the NCBI GEO database (accession number: GSE10524). (D) Comparison of the gene expression levels of TIM‐1 and IL‐10 between PCNSL (n = 34), normal brain (n = 23), astrocytoma (n = 26), glioblastoma (n = 81), and oligodendroglioma (n = 50) samples using microarray datasets available in the NCBI GEO database (accession numbers: GSE4290 and GSE34771). DLBCL, diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma.

We next compared the mRNA expression levels of TIM‐1 and IL‐10 in PCNSL and nodal DLBCL by using datasets from the GEO database (accession number: GSE10524 26). The expression of the TIM‐1 gene was shown to be significantly higher in PCNSL than in nodal DLBCL (P < 0.001), and the expression of IL‐10 also tended to be higher in PCNSL (Fig. 1C). Additionally, we collected two datasets (accession number: GSE4290 27 and GSE34771 28) measured on the same GPL570 microarray platform, and after normalization using the RMA method, expression levels of TIM‐1 and IL‐10 were compared. We found that both genes were expressed significantly higher in PCNSL than in normal brain or other brain tumors (P < 0.001, Fig. 1D). These results suggest that Tim‐1 is expressed in PCNSL with high specificity at both mRNA and protein levels, and it tends to positively correlate with IL‐10 expression.

Tim‐1 enhances IL‐10 expression in PCNSL

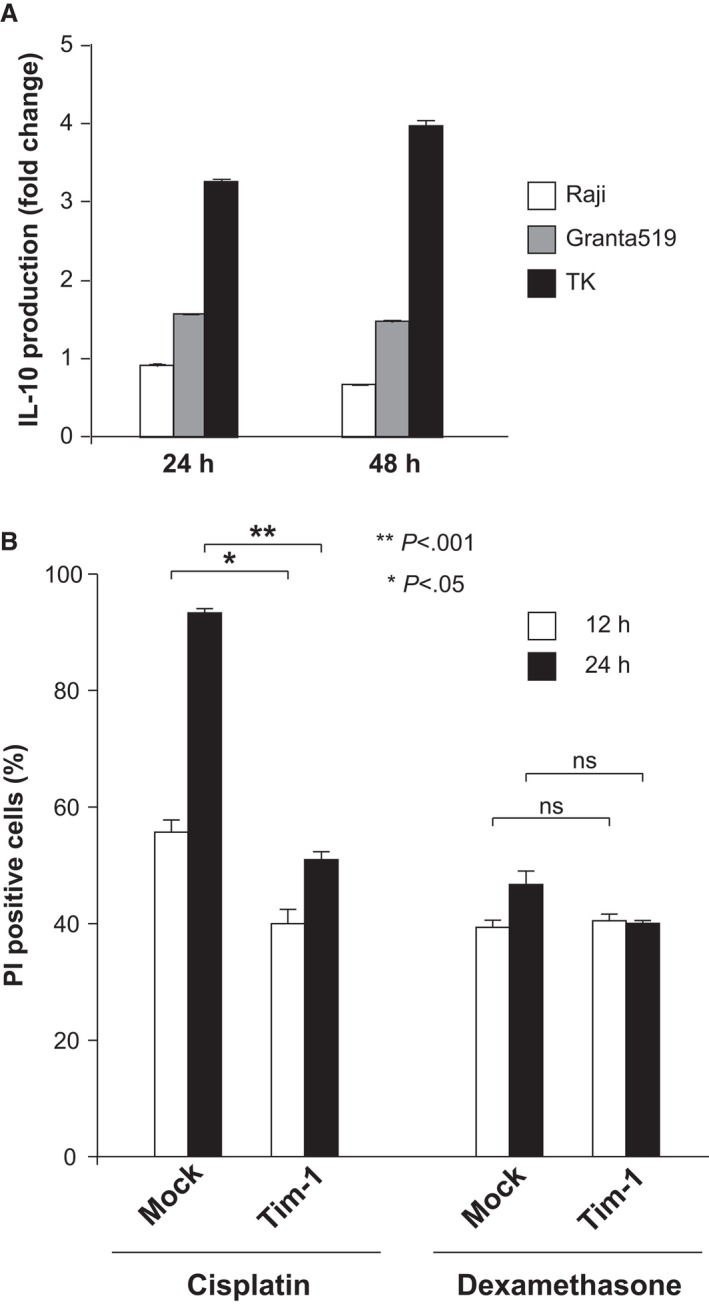

Next, we intended to clarify the biological relationship between Tim‐1 and IL‐10 expression. In a PCNSL‐derived cell line, TK, endogenous Tim‐1 protein is expressed at a low level. We lentivirally introduced TIM‐1‐expressing or mock vector into TK cells, and compared their IL‐10 production by ELISA. Notably, the enhanced expression of Tim‐1 resulted in increased IL‐10 production in TK cells but not in other B‐cell lymphoma lines, Raji and Granta 519 (Fig. 2A), suggesting that Tim‐1 augments IL‐10 expression in a PCNSL‐specific cell condition.

Figure 2.

The functional role of Tim‐1 played in PCNSL cells. (A) Comparison of fold changes in IL‐10 production of Raji, Granta519, and TK cells introduced with TIM‐1‐expressing and mock vectors. (B) Cell death rates of TK cells introduced with TIM‐1‐expressing or mock vectors, which were evaluated by propidium iodide (PI) staining after culturing with cisplatin or dexamethasone for indicated periods.

To examine whether Tim‐1 has any role in the survival of PCNSL cells, we cultured TIM‐1 and mock‐introduced TK cells with cisplatin or dexamethasone. Although the presence of Tim‐1 did not obviously alter cell susceptibility to dexamethasone, it decreased the rate of cell death caused by cisplatin (Fig. 2B), suggesting that Tim‐1 may also confer chemoresistance on PCNSL cells.

Soluble Tim‐1 in the CSF of PCNSL patients

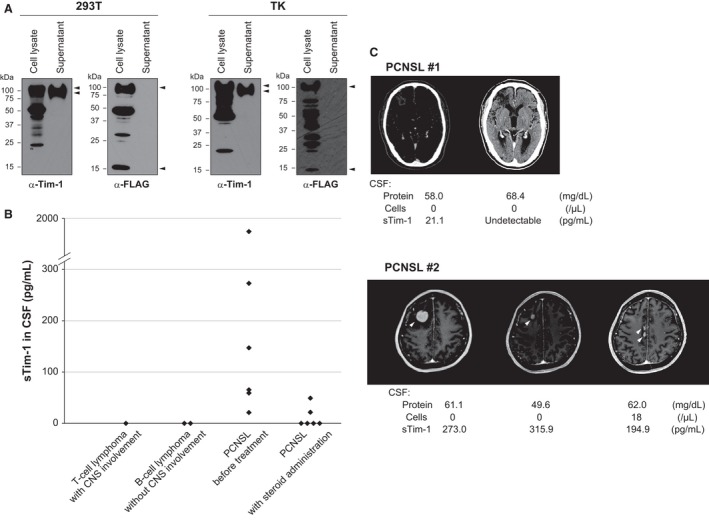

As Tim‐1 is expressed in tubular epithelial cells following kidney injury 13 and its soluble form is reported to be released into the urine 14, 15, 16, we examined whether the soluble form of Tim‐1 is also released from PCNSL cells. We transfected TIM‐1 expression vector into 293T and TK cells, and their supernatants were examined for Tim‐1 protein by immunoblotting (Fig. 3A). Tim‐1 was detected in each supernatant by anti‐Tim‐1 antibody, which reacts with the extracellular domain of the protein, and it was slightly smaller in size than those observed in the cell lysate. On the other hand, Tim‐1 protein was not detected in the supernatant when anti‐FLAG antibody was used, which reacts with the FLAG epitope on the C‐terminus, suggesting that the soluble form of this protein lacks the C‐terminus. Instead, a small remnant protein was detected in the cell lysate by this antibody. These results suggest that, as is reported in tubular epithelial cells, Tim‐1 is cleaved near the C‐terminus and its extracellular domain is released from these cells.

Figure 3.

Shedding of Tim‐1 ectodomain and detection of soluble Tim‐1 in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of PCNSL patients. (A) Immunoblot analysis of 293T and TK cells transfected with TIM‐1 expression vector. The cells and supernatants were separately analyzed for Tim‐1 protein using anti‐Tim‐1 and anti‐FLAG antibodies, which recognize the extracellular domain and FLAG on the C‐terminus, respectively. Arrowheads indicate different forms of Tim‐1 protein: full‐length form (cell lysate), soluble form without C‐terminus (supernatant), and remnant protein (cell lysate). (B) Soluble Tim‐1 levels in the CSF of lymphoma patients analyzed by ELISA. (C) Clinical course of the two representative PCNSL patients. PCNSL #1: Tim‐1 in CSF became undetectable after successful treatment of whole‐brain irradiation. PCNSL #2: Tim‐1 level remained high after chemotherapy while radiological examination of the tumor suggested a good response to the treatment. The patient subsequently relapsed with multiple brain lesions and CSF dissemination.

These results led us to examine whether the soluble form of Tim‐1 is also released from PCNSL cells in vivo, and we examined Tim‐1 protein in the CSF of lymphoma patients by ELISA (Fig. 3B). Among 12 CSF samples obtained from PCNSL patients before treatment, Tim‐1 was detected in eight, and the rest four samples were of patients who had been administered systemic steroids before sampling. On the other hand, Tim‐1 was not detected in the CSF of a T‐cell lymphoma patient with secondary CNS involvement, or systemic DLBCL patients without CNS involvement. Soluble Tim‐1 became undetectable in the patients who had achieved complete remission, but it remained positive in the patients with refractory disease (Fig. 3C). In PCNSL patient #2, radiological examination of the tumor suggested a good response to chemotherapy, although Tim‐1 level in the CSF remained high. After 2 months, the patient relapsed with numerous small brain lesions and CSF dissemination. These results suggest that soluble Tim‐1 in the CSF can also reflect the presence of radiologically undetectable tumor cells, and it is expected to serve as a useful biomarker for PCNSL.

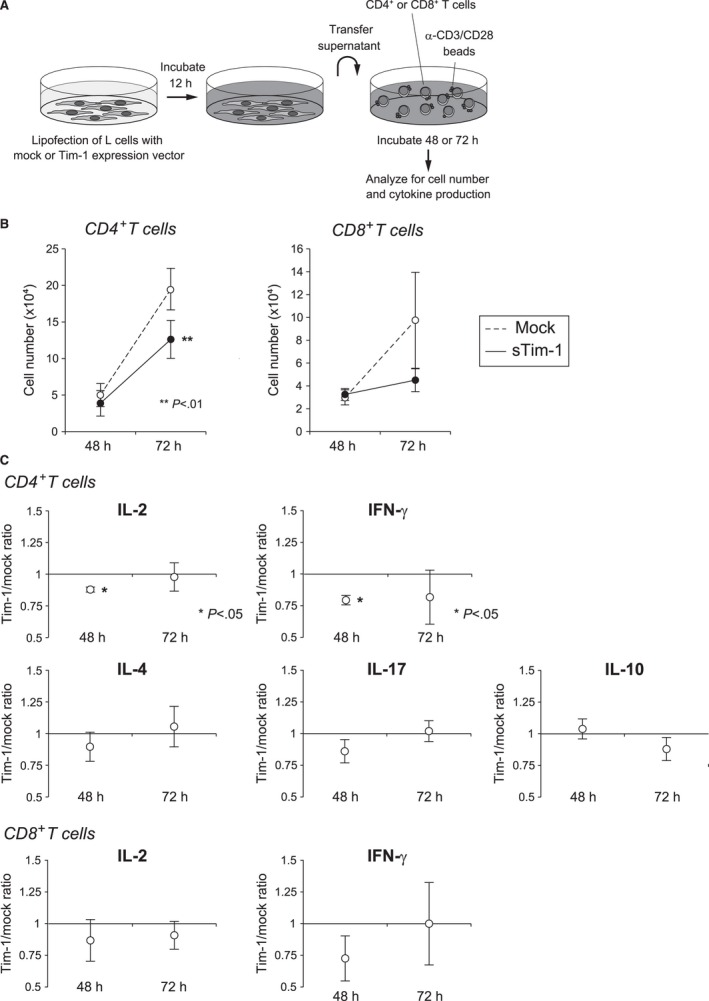

Role of Tim‐1 in the tumor microenvironment

To clarify whether soluble Tim‐1 has any role in the tumor microenvironment, we examined its effect on T‐cell function. We collected peripheral CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from healthy donors, and stimulated them with anti‐CD3/CD28 beads in vitro in the presence or absence of soluble Tim‐1 produced by L cells (Fig. 4A). We found that the proliferation of CD4+ T cells was suppressed by soluble Tim‐1 (P < 0.01), and proliferation of CD8+ T cells also tended to be inhibited (Fig. 4B). Additionally, IL‐2 and IFN‐γ production of CD4+ T cells after 48 h of culture was suppressed in the presence of soluble Tim‐1, whereas the production of other cytokines was less affected (Fig. 4C). According to these results, it is suggested that the soluble form of Tim‐1 released from PCNSL cells has some immunomodulatory functions, and it may have a potential role in creating a microenvironment favorable for tumor cells.

Figure 4.

Immunomodulatory effect of soluble Tim‐1. (A) Schematic diagram of the experiment. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of the healthy donors were stimulated with anti‐CD3/CD28 beads with or without soluble Tim‐1 produced by L cells, and analyzed for cell proliferation and cytokine production. Soluble form of Tim‐1 was detected in the supernatant of L cells transfected with TIM‐1 expression vector but not with mock vector (data not shown). (B) Effect of soluble Tim‐1 on T‐cell number. (C) Effect of soluble Tim‐1 on cytokine production of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

Discussion

In this study, we have reported that Tim‐1, a molecule known as a specific marker for regulatory B cells in mice, is characteristically expressed in PCNSL. About 90–95% of PCNSLs demonstrate DLBCL histology, whereas they exhibit some distinct clinical features from systemic DLBCL, such as site‐confined progression and high responsiveness to methotrexate therapy 29. Histological and molecular studies of PCNSL to date have revealed the frequent expression of MUM‐1 and Bcl‐6 30, 31, 32, high proliferative activity 33, recurrent BCL6 translocation, and deletion of 6p21.3 34. NF‐κB pathway is generally activated in PCNSL, and gene alterations that lead to its deregulation, such as activating mutations of CARD11 and MYD88, are often involved 35, 36, 37, 38.

Four functional TIM genes in mice and three in humans (TIM‐1, TIM‐3, and TIM‐4) have been identified to date, and these TIM family members have multiple roles in regulating immune response. Tim‐1 functions as a costimulatory molecule following T‐cell receptor (TCR) signaling, particularly after Th2 polarization 7, 8, 9. Additionally, Tim‐1 has been reported to be a major ligand for endothelial P‐selectin, and have a function to regulate T‐cell trafficking in inflamed tissues 39, 40. Tim‐1 is also expressed in other immune cells such as dendritic cells and mast cells, and plays different roles in each cell type 41, 42, 43, 44.

As for B cells, Tim‐1 was reported to be expressed on a population that has immunosuppressive function, called regulatory B cells, in mice 5. Tim‐1‐positive B cells were shown to be highly enriched for IL‐10 and IL‐4 expression, promote Th2 responses, and be able to transfer allograft tolerance directly. These immunosuppressive B cells have been indicated to participate in the alleviation of brain inflammation in mouse models of multiple sclerosis (EAE) and cerebral infarction 2, 3, 4. Little information is available on the function of B cells in the human brain, but there is a report of nonvasculitic autoimmune meningoencephalitis that developed after rituximab therapy against rheumatoid arthritis 45. Brain biopsy showed a lack of B cells in the brain tissue, and the authors hypothesize that the depletion of regulatory B cells potentially triggered the autoimmune reaction in the brain.

We found high expression of Tim‐1 in PCNSL by histological analysis of the clinical samples. Gene expression analysis using the GEO database also found high Tim‐1 expression in PCNSL compared to other brain tumors, although we were not able to compare with inflammatory brain disorders. Tim‐1 tended to be expressed concurrently with IL‐10, and it was suggested to enhance IL‐10 production in PCNSL cells. Such association between Tim‐1 and IL‐10 was not observed in other B‐cell lines, and is considered to be specific to PCNSL cells. Mouse regulatory B cells with defective Tim‐1 were reported to exhibit low IL‐10 expression 17, suggesting that Tim‐1 is necessary for IL‐10 production in regulatory B cells. The relationship between Tim‐1 and IL‐10 in PCNSL suggests biological similarity of PCNSL to regulatory B cells.

We also found that the extracellular domain of Tim‐1 is released from PCNSL cells, and soluble Tim‐1 is detected in the CSF of PCNSL according to disease activity. An increased IL‐10/IL‐6 ratio in the CSF is known to be useful for the diagnosis of PCNSL, but it is often difficult to measure accurately in clinical practice because of its instability. The half‐life of Tim‐1 is longer than that of IL‐10 (about 6 h vs 1–2.6 h) 46, 47, 48, and it can be a more clinically applicable biomarker, although further examination is required. In contrast, serum Tim‐1 levels varied among healthy controls irrespective of renal function in our preliminary analysis, and it did not seem to be useful as a biomarker.

In summary, we found that Tim‐1 is characteristically expressed in PCNSL. In addition to its potential usefulness as a clinical biomarker, Tim‐1 is expected to be a key molecule for the better understanding and improved clinical management of PCNSL.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose with regard to this report.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yoshiki Arakawa, Department of Neurosurgery, Kyoto University, and Dr. Masakazu Fujimoto and Mr. Masahiro Hirata, Department of Diagnostic Pathology, Kyoto University Hospital, for their assistance in this study. This work was supported in part by grants‐in‐aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (24591391, 15K09474). No financial interest/relationships with financial interest relating to the topic of this article have been declared.

Cancer Medicine 2016; 5(11):3235–3245

References

- 1. Deckert, M. , Engert A., Bruck W., Ferreri A. J., Finke J., Illerhaus G., et al. 2011. Modern concepts in the biology, diagnosis, differential diagnosis and treatment of primary central nervous system lymphoma. Leukemia 25:1797–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Matsushita, T. , Yanaba K., Bouaziz J. D., Fujimoto M., and Tedder T. F.. 2008. Regulatory B cells inhibit EAE initiation in mice while other B cells promote disease progression. The J. Clin. Invest. 118:3420–3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ren, X. , Akiyoshi K., Dziennis S., Vandenbark A. A., Herson P. S., Hurn P. D., et al. 2011. Regulatory B cells limit CNS inflammation and neurologic deficits in murine experimental stroke. J. Neurosci. 31:8556–8563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Offner, H. , and Hurn P. D.. 2012. A novel hypothesis: regulatory B lymphocytes shape outcome from experimental stroke. Transl. Stroke Res. 3:324–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ding, Q. , Yeung M., Camirand G., Zeng Q., Akiba H., Yagita H., et al. 2011. Regulatory B cells are identified by expression of TIM‐1 and can be induced through TIM‐1 ligation to promote tolerance in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121:3645–3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rennert, P. D. 2011. Novel roles for TIM‐1 in immunity and infection. Immunol. Lett. 141:28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meyers, J. H. , Chakravarti S., Schlesinger D., Illes Z., Waldner H., Umetsu S. E., et al. 2005. TIM‐4 is the ligand for TIM‐1, and the TIM‐1‐TIM‐4 interaction regulates T cell proliferation. Nat. Immunol. 6:455–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Umetsu, S. E. , Lee W. L., McIntire J. J., Downey L., Sanjanwala B., Akbari O., et al. 2005. TIM‐1 induces T cell activation and inhibits the development of peripheral tolerance. Nat. Immunol. 6:447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. de Souza, A. J. , Oriss T. B., O'Malley K. J., Ray A., and Kane L. P.. 2005. T cell Ig and mucin 1 (TIM‐1) is expressed on in vivo‐activated T cells and provides a costimulatory signal for T cell activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:17113–17118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xiao, S. , Najafian N., Reddy J., Albin M., Zhu C., Jensen E., et al. 2007. Differential engagement of Tim‐1 during activation can positively or negatively costimulate T cell expansion and effector function. J. Exp. Med. 204:1691–1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Degauque, N. , Mariat C., Kenny J., Zhang D., Gao W., Vu M. D., et al. 2008. Immunostimulatory Tim‐1‐specific antibody deprograms Tregs and prevents transplant tolerance in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 118:735–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ueno, T. , Habicht A., Clarkson M. R., Albin M. J., Yamaura K., Boenisch O., et al. 2008. The emerging role of T cell Ig mucin 1 in alloimmune responses in an experimental mouse transplant model. J. Clin. Invest. 118:742–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ichimura, T. , Bonventre J. V., Bailly V., Wei H., Hession C. A., Cate R. L., et al. 1998. Kidney injury molecule‐1 (KIM‐1), a putative epithelial cell adhesion molecule containing a novel immunoglobulin domain, is up‐regulated in renal cells after injury. J. Biol. Chem. 273:4135–4142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Han, W. K. , Bailly V., Abichandani R., Thadhani R., and Bonventre J. V.. 2002. Kidney Injury Molecule‐1 (KIM‐1): a novel biomarker for human renal proximal tubule injury. Kidney Int. 62:237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ichimura, T. , Hung C. C., Yang S. A., Stevens J. L., and Bonventre J. V.. 2004. Kidney injury molecule‐1: a tissue and urinary biomarker for nephrotoxicant‐induced renal injury. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 286:F552–F563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liangos, O. , Tighiouart H., Perianayagam M. C., Kolyada A., Han W. K., Wald R., et al. 2009. Comparative analysis of urinary biomarkers for early detection of acute kidney injury following cardiopulmonary bypass. Biomarkers 14:423–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xiao, S. , Brooks C. R., Zhu C., Wu C., Sweere J. M., Petecka S., et al. 2012. Defect in regulatory B‐cell function and development of systemic autoimmunity in T‐cell Ig mucin 1 (Tim‐1) mucin domain‐mutant mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:12105–12110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hans, C. P. , Weisenburger D. D., Greiner T. C., Gascoyne R. D., Delabie J., Ott G., et al. 2004. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood 103:275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gautier, L. , Cope L., Bolstad B. M., and Irizarry R. A.. 2004. affy–analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip data at the probe level. Bioinformatics 20:307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yamamoto, R. , Nishikori M., Kitawaki T., Sakai T., Hishizawa M., Tashima M., et al. 2008. PD‐1‐PD‐1 ligand interaction contributes to immunosuppressive microenvironment of Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 111:3220–3224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hishizawa, M. , Imada K., Sakai T., Ueda M., and Uchiyama T.. 2005. Identification of APOBEC3B as a potential target for the graft‐versus‐lymphoma effect by SEREX in a patient with mantle cell lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 130:418–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shinohara, M. , Io K., Shindo K., Matsui M., Sakamoto T., Tada K., et al. 2012. APOBEC3B can impair genomic stability by inducing base substitutions in genomic DNA in human cells. Sci. Rep. 2:806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meertens, L. , Carnec X., Lecoin M. P., Ramdasi R., Guivel‐Benhassine F., Lew E., et al. 2012. The TIM and TAM families of phosphatidylserine receptors mediate dengue virus entry. Cell Host Microbe 12:544–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moreau, T. , Barlogis V., Bardin F., Nunes J. A., Calmels B., Chabannon C., et al. 2008. Development of an enhanced B‐specific lentiviral vector expressing BTK: a tool for gene therapy of XLA. Gene Ther. 15:942–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sakai, T. , Nishikori M., Tashima M., Yamamoto R., Kitawaki T., Takaori‐Kondo A., et al. 2009. Distinctive cell properties of B cells carrying the BCL2 translocation and their potential roles in the development of lymphoma of germinal center type. Cancer Sci. 100:2361–2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Booman, M. , Szuhai K., Rosenwald A., Hartmann E., Kluin‐Nelemans H., de Jong D., et al. 2008. Genomic alterations and gene expression in primary diffuse large B‐cell lymphomas of immune‐privileged sites: the importance of apoptosis and immunomodulatory pathways. J. Pathol. 216:209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sun, L. , Hui A. M., Su Q., Vortmeyer A., Kotliarov Y., Pastorino S., et al. 2006. Neuronal and glioma‐derived stem cell factor induces angiogenesis within the brain. Cancer Cell 9:287–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kawaguchi, A. , Iwadate Y., Komohara Y., Sano M., Kajiwara K., Yajima N., et al. 2012. Gene expression signature‐based prognostic risk score in patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 18:5672–5681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Korfel, A. , and Schlegel U.. 2013. Diagnosis and treatment of primary CNS lymphoma. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 9:317–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Braaten, K. M. , Betensky R. A., de Leval L., Okada Y., Hochberg F. H., Louis D. N., et al. 2003. BCL‐6 expression predicts improved survival in patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 9:1063–1069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Camilleri‐Broet, S. , Criniere E., Broet P., Delwail V., Mokhtari K., Moreau A., et al. 2006. A uniform activated B‐cell‐like immunophenotype might explain the poor prognosis of primary central nervous system lymphomas: analysis of 83 cases. Blood 107:190–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Preusser, M. , Woehrer A., Koperek O., Rottenfusser A., Dieckmann K., Gatterbauer B., et al. 2010. Primary central nervous system lymphoma: a clinicopathological study of 75 cases. Pathology 42:547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Deckert‐Schluter, M. , Rang A., and Wiestler O. D.. 1998. Apoptosis and apoptosis‐related gene products in primary non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 96:157–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Riemersma, S. A. , Jordanova E. S., Schop R. F., Philippo K., Looijenga L. H., Schuuring E., et al. 2000. Extensive genetic alterations of the HLA region, including homozygous deletions of HLA class II genes in B‐cell lymphomas arising in immune‐privileged sites. Blood 96:3569–3577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Courts, C. , Montesinos‐Rongen M., Martin‐Subero J. I., Brunn A., Siemer D., Zuhlke‐Jenisch R., et al. 2007. Transcriptional profiling of the nuclear factor‐kappaB pathway identifies a subgroup of primary lymphoma of the central nervous system with low BCL10 expression. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 66:230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Montesinos‐Rongen, M. , Schmitz R., Brunn A., Gesk S., Richter J., Hong K., et al. 2010. Mutations of CARD11 but not TNFAIP3 may activate the NF‐kappaB pathway in primary CNS lymphoma. Acta Neuropathol. 120:529–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nakamura, T. , Tateishi K., Niwa T., Matsushita Y., Tamura K., Kinoshita M., et al. 2016. Recurrent mutations of CD79B and MYD88 are the hallmark of primary central nervous system lymphomas. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 42:279–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hattori, K. , Sakata‐Yanagimoto M., Okoshi Y., Goshima Y., Yanagimoto S., Nakamoto‐Matsubara R., et al. 2016. MYD88 (L265P) mutation is associated with an unfavourable outcome of primary central nervous system lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. DOI:10.1111/bjh.14080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Angiari, S. , Donnarumma T., Rossi B., Dusi S., Pietronigro E., Zenaro E., et al. 2014. TIM‐1 glycoprotein binds the adhesion receptor P‐selectin and mediates T cell trafficking during inflammation and autoimmunity. Immunity 40:542–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Angiari, S. , and Constantin G.. 2014. Regulation of T cell trafficking by the T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 1 glycoprotein. Trends Mol. Med. 20:675–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kuchroo, V. K. , Dardalhon V., Xiao S., and Anderson A. C.. 2008. New roles for TIM family members in immune regulation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8:577–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kane, L. P. 2010. T cell Ig and mucin domain proteins and immunity. J. Immunol. 184:2743–2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Xiao, S. , Zhu B., Jin H., Zhu C., Umetsu D. T., DeKruyff R. H., et al. 2011. Tim‐1 stimulation of dendritic cells regulates the balance between effector and regulatory T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 41:1539–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nakae, S. , Iikura M., Suto H., Akiba H., Umetsu D. T., Dekruyff R. H., et al. 2007. TIM‐1 and TIM‐3 enhancement of Th2 cytokine production by mast cells. Blood 110:2565–2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hadley, I. , Jain R., and Sreih A.. 2014. Nonvasculitic autoimmune meningoencephalitis after rituximab: the potential downside of depleting regulatory B cells in the brain. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 20:163–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bailly, V. , Zhang Z., Meier W., Cate R., Sanicola M., and Bonventre J. V.. 2002. Shedding of kidney injury molecule‐1, a putative adhesion protein involved in renal regeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 277:39739–39748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Le, T. , Leung L., Carroll W. L., and Schibler K. R.. 1997. Regulation of interleukin‐10 gene expression: possible mechanisms accounting for its upregulation and for maturational differences in its expression by blood mononuclear cells. Blood 89:4112–4119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Li, M. C. , and He S. H.. 2004. IL‐10 and its related cytokines for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 10:620–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]