Abstract

Stroke is a disease of aging affecting millions of people worldwide, and recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (r-tPA) is the only treatment approved. However, r-tPA has a low therapeutic window and secondary effects which limit its beneficial outcome, urging thus the search for new more efficient therapies. Among them, neuroprotection based on melatonin or nitrones, as free radical traps, have arisen as drug candidates due to their strong antioxidant power. In this Perspective article, an update on the specific results of the melatonin and several new nitrones are presented.

Keywords: stroke, neuroprotection, oxidative stress, melatonin, nitrones

Introduction

Stroke is a disease of aging, affecting an increasing number of people worldwide, and the main cause of disability (Flynn et al., 2008; Mathers et al., 2009). The ischemic cascade begins with the energy failure produced by the obstruction of a blood vessel that produces a massive and prolonged release of glutamate (Rothman and Olney, 1986). Physiopathological events associated with brain ischemia are related to oxidative stress process, Ca2+ dyshomeostasis, mitochondrial dysfunction, pro-inflammatory mediators and/or programmed neuronal cell death. In the ischemic stroke, as the result of the obstruction of a blood vessel, a critical reduction in the cerebral blood flow (less than 25%) occurred in brain, and neurons need a continued supply of oxygen and glucose. Under deprivation of oxygen and glucose, cell death occurs in two phases: (a) first cell death from anoxia/hypoxia and energy depletion, followed by; and (b) reperfusion that increase oxidative stress and free radical formation, excitotoxicity and nitric oxide (NO) production with ulterior energy failure and delayed death (Hossmann, 1994; Choi, 1996; Lee et al., 1999; Ito et al., 2003).

No effective therapeutic drugs to treat or prevent brain damage in ischemic stroke are currently available. Only recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (r-tPA) is used to open a blood vessel, but r-tPA has a very narrow therapeutic window of 3.5 h (Zivin et al., 1985). Preventing brain damage during the ischemic penumbra, despite that it is a hypoperfused and non-functional tissue, is still a viable tissue adjacent to the infarcted core. Finally, new therapeutic agents are needed to recover tissue functionality before cell death, and to be effective in dealing with several targets, including excitotoxicity and disturbed calcium ion homeostasis, mitochondrial failure, oxidative and nitrosative stress, inflammation and apoptosis (Paschen, 2000; Chan, 2001; Iadecola and Alexander, 2001; Lo E. H. et al., 2005; Niizuma et al., 2010). In this Perspective article, we will focus on melatonin and nitrones, well-known radical scavenging and antioxidant agents, for the potential therapy of stroke (Hardeland, 2009).

Melatonin

Stroke as a main cause of brain disease arouses great interest in therapeutic strategies development. The fact that no effective treatment for stroke has yet been approved to date makes melatonin a promising molecule for stroke treatment, either alone or in combination with other agents. A great number of studies had been developed with melatonin prevention or counteracting stroke damage at several steps of the ischemic cascade, such as neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, excitotoxicity and/or apoptosis (Barlow-Walden et al., 1995; Sinha et al., 2001; Rodriguez et al., 2004; Ozacmak et al., 2009; Reiter et al., 2009; Koh, 2012a; Kim and Lee, 2014; Manchester et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2015; Alluri et al., 2016). We have recently demonstrated that in rat hippocampal slices subjected to oxygen-glucose-deprivation (OGD) and glutamate excitotoxicity, melatonin is able to mediate neuroprotection (Patiño et al., 2016). Previously, we also demonstrated that melatonin exerts its protective effect post-ischemia through the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α7 subunit modulated by an overexpression of heme oxygenase-1 (Parada et al., 2014).

Numerous experimental in vivo studies evidenced that doses in a range of 5–15 mg/kg of melatonin, mainly administered intraperitoneally, exert neuroprotective effects in the ischemic cascade at several critical points (Guerrero et al., 1997; Pei et al., 2003; Pei and Cheung, 2004; Chen H. Y. et al., 2006; Carloni et al., 2008; Signorini et al., 2009; Balduini et al., 2012; Alonso-Alconada et al., 2013; Paredes et al., 2015).

In vivo data confirm the efficacy of this indoleamine. Melatonin has been related to brain repair by comparing pinealectomized and non-pinealectomized animals, observing a greater neurodegeneration in the last group (Manev et al., 1996). Some studies showed its capacity to counteract oxidative stress downregulation or scavenging oxygen and nitrogen species and its free radical detoxification capacity (Guerrero et al., 1997; Pei et al., 2003; Rodriguez et al., 2004; Chen H. Y. et al., 2006; Koh, 2008d).

Other results in stroke models reveal the efficacy of the antiapoptotic properties of melatonin through several mechanisms like increasing levels of Bcl-2, blocking caspase cascade or by preventing mitochondrial depolarization (Sun et al., 2002; Andrabi et al., 2004; Koh, 2008b).

In stroke, elevated extracellular glutamate is critical in neuronal damage. Herein, melatonin has also demonstrated a neuroprotective effect in vivo, mitigating Ca2+ influx (Camello-Almaraz et al., 2008) via melatonin receptor (Das et al., 2010) by reducing lipid peroxidation (Kim and Kwon, 1999; Wakatsuki et al., 2001). Interestingly, melatonin is a free radical scavenger, which inhibits NO synthesis, a mediator of glutamate and therefore reducing the excitotoxicity (Chung and Han, 2003). In animal stroke models, inflammation leads to numerous pathological events, but melatonin treatment reduces macrophage brain infiltration, activated microglia prevents IL-1β, TNF-α and GFAP overexpression (Lee et al., 2007; Paredes et al., 2015), which taken together inhibit the inflammatory response.

Nonetheless, blood brain barrier (BBB) integrity is compromised after cerebrovascular insults, by an increased release of proinflammatory mediators (COX-2, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6), ROS, protein extravasation and interstitial edema. In animal models, melatonin significantly reduces BBB dysfunction through several mechanisms, NO, ROS and RNS levels, preserves tight junction proteins as claudin-5 and modulates hyperpermeability (Chen H. Y. et al., 2006; Grossetete et al., 2009; Song et al., 2014; Moretti et al., 2015; Alluri et al., 2016). In light of these results melatonin shows a suitable profile to preserve BBB functional integrity.

Among brain cell populations, neural stem cells (NSCs) have the potential to regenerate new neuronal population. It has been described that after a melatonin treatment, neurogenesis is induced through melatonin receptor MT2 (Chern et al., 2012). Despite molecular neuroprotective mechanisms are not well defined, melatonin has demonstrated to enhance neurogenic cells of the ischemic brain, in striatum neurons and the hippocampal region (Kilic et al., 2008; Ayao et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2014). Furthermore, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are used in implantations after the ischemic insult, but unfortunately this procedure involves the difficulty that approximately the 80% of the grafted cells do not survive (Roh et al., 2008). Melatonin pre-administration achieves a higher percentage of MSCs survival, also through a receptor-mediated mechanism (Tang et al., 2014).

As far as signal transduction pathways are involved in stroke, melatonin has emerged as a versatile neuroprotective regulator. Melatonin neuroprotective effects are achieved through receptor-mediated mechanisms (MT1, MT2 and MT3; Reiter et al., 2007; Tan et al., 2007; Slominski et al., 2012; Lacoste et al., 2015). Activation of MT1 melatonin receptor leads to the stimulation of a large variety of G proteins (Brydon et al., 1999), upregulation of MT2 promoted neurogenesis and preservation of BBB integrity (Chern et al., 2012) and stimulation of MT3 may contribute to the antioxidant potential of melatonin (Tan et al., 2007).

In addition, melatonin is highly effective in preventing Ca2+ dyshomeostasis during ischemic brain injury (Camello-Almaraz et al., 2008; Koh, 2012b). The antiapoptotic effect of melatonin in brain ischemia models is related to its actions at the mitochondria level, preventing the injury-induced reduction of pBad levels and the mitochondrial depolarization inhibiting the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP; Andrabi et al., 2004; Kilic et al., 2004b; Koh, 2008b). Cell proliferation, differentiation, survival and apoptosis are regulated by the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and activation of iNOS signaling is associated with PI3K/Akt inhibition. It has been reported that melatonin upregulates this pathway, and decreases iNOS levels (Kilic et al., 2005; Koh, 2008c,d). Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a family of calcium-dependent zinc-binding proteolytic enzymes that degrade the extracellular matrix (ECM) components of the basement membrane (Montaner et al., 2001). Administration of exogenous melatonin attenuated postischemic MMP-9 activation reducing brain damage in stroke models (Hung et al., 2008). The mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase/extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2 signaling pathway regulates cell differentiation, growth, survival and apoptosis (Pearson et al., 2001). It has been reported that melatonin plays neuroprotection through Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation, and activates MEK/ERK/p90RSK/Bad cascade signaling (Kilic et al., 2005; Koh, 2008a). After hypoxic/ischemic brain injury, endogenous vasoconstrictor endothelin-1 (ET-1) levels are elevated leading to exacerbated brain injury, but when melatonin is administered in mice stroke models a beneficial neuroprotective effect was observed inhibiting ET-1 (Kilic et al., 2004a; Lo A. C. et al., 2005). Phosphorylation/dephosphorylation processes are the major form of cellular signaling (Gong and Iqbal, 2008), and their deregulation turns in severe pathologies including neurodegeneration (Sontag et al., 2004), cancer (Ruediger et al., 2001), cardiovascular (Ling et al., 2012) and metabolic disorders (Mandavia and Sowers, 2012). The phosphoprotein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) is the principal member of the family of Ser/Thr phosphatases (Liu et al., 2005), which removes phosphate from serine and threonine residues. Several compounds may activate or protect PP2A enzyme activity and have neuroprotective actions in in vivo and in vitro models of brain damage (Shah et al., 2015). In this context, melatonin exerts an upregulation of PP2A enzyme activity, which implies that the PP2A malfunction observed in excitotoxic environments could be mitigated by the administration of melatonin (Koh, 2012a). The protective effect of Silent information regulator 1 (SIRT1) on the brain has been well demonstrated (Yang et al., 2013). Melatonin preserves SIRT1 expression, activates SIRT1 signaling in neuronal cells after hypoxia-ischemia attenuating mitochondrial oxidative damage (Carloni et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2015).

Finally, melatonin has been combined with other drugs, such as t-PA (Chen T. Y. et al., 2006), topiramate (Ozyener et al., 2012), nimodipine and other Ca2+ antagonists (Gelmers et al., 1988; Toklu et al., 2009), meloxicam (Gupta et al., 2002) for stroke therapy, giving promising results.

Nitrones

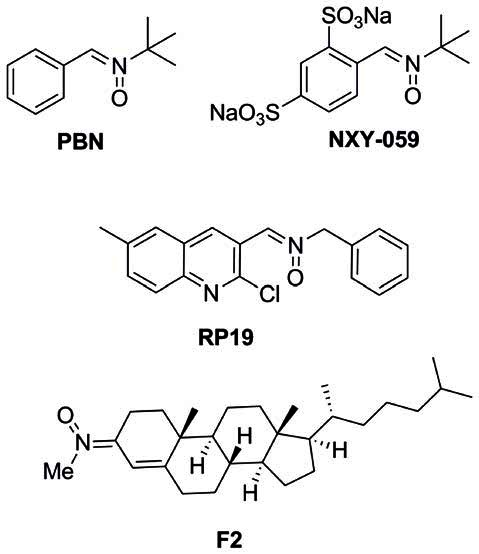

Based on the understanding of the biochemical processes involved in the formation and development of a stroke, number of products have been developed targeting the different ischemic and reperfusion events. Despite the promising initial results, neuroprotection drugs for stroke have failed in advanced clinical phases, and consequently, no neuroprotective agent has been approved by the FDA for stroke therapy. However, neuroprotection is still a choice, and oxidative stress, a suitable biological target. In this context, antioxidants such as N-t-butylphenylnitrone (PBN; Figure 1; Novelli et al., 1986) and NXY-059 (Figure 1; Dehouck et al., 2002), have attracted the interest of a number of laboratories, resulting in therapeutic candidates for cancer (Inoue et al., 2007; Floyd et al., 2008, 2010, 2011; Costa et al., 2015), neurodegenerative disorders (Floyd et al., 2000), hearing loss (Floyd et al., 2008) and stroke (Doggrell, 2006; Floyd et al., 2008). NXY-059 (Figure 1) (Kuroda et al., 1999) is a well-known free radical scavenger with good neuroprotective profile in rat models of transient and permanent focal ischemia, and stroke model in rodents, which has been launched several times in different program in advanced clinical studies, although with limited success (Macleod et al., 2008). In fact and in addition, tert-butylnitrones, such as NXY-059, are known to afford t-butylhydroxylamines as powerful radical scavengers, after hydrolysis, that further could be oxidized to 2-methyl-2-nitrosopropane which then may synthesize NO radical, the source and origin of the neuroprotection, as it has been already reported for NO donors (Godínez-Rubí et al., 2013). Recently reported new developments have highlighted the not previously described and powerful neuroprotective effect shown by new PBN derivatives bearing N-aryl substituents on human neuroblastoma cells, under induced in vitro experimental oxidative stress (Matias et al., 2016).

Figure 1.

Structures of nitrones N-t-butylphenylnitrone (PBN), NXY-059, and the nitrones RP19 and F2, assesed in our laboratories.

Starting in 2008, the group led by Marco-Contelles (CSIC, Madrid, Spain) has designed, synthesized and developed a number of nitrones for the potential treatment of stroke, the most interesting compounds being RP19 (Figure 1; Chioua et al., 2012), and F2 (Ayuso et al., 2015; Figure 1), in collaboration with Dr. Dimitra J. Hadjipavlou-Litina (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece) and Dr. Alcázar (Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain).

As radical-trapping agents, nitrones are expected to delay or prevent oxidation of easily oxidizable substrates, therefore being considered antioxidants. In vitro radical trapping and antioxidant activity were studied for nitrones RP19 and F2, and PBN as reference compound, using the DPPH quenching, •OH and scavenging, and inhibition of lipid peroxidation by AAPH tests. As shown in Table 1A, DPPH and scavenging activities were low in general, with moderate values for RP19 (42.3% and 23%). Scavenging of •OH, as one of the most toxic radicals generated during ischemic stress, was also determined, showing that higher trapping activities were achieved than reference compound PBN.

Table 1A.

In vitro antioxidant activity (A) and neuroprotection in neuronal cultures and in vivo model of ischemia (B).

| Nitrone | AAPH (%)a (min)b | DPPH (%)c | ·OH (%)d | (%)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP19g | 37 (78) | 42.3 | 95 | 23 |

| F2h | 55 (nd)f | 4 | 83 | (nd)f |

| PBN | no (0) | (nd)f | 90 | 15 |

Testing in neuronal cultures and in in vivo experiments were next evaluated. Thus, the neuroprotective effect of nitrones RP19, F2, as well as PBN and NXY-059 as standards were studied in primary neuronal cultures, which were subjected to OGD as an in vitro model of ischemia. Cell viability was evaluated by quantification of living, metabolically active cells, as determined by the MTT assay. Neuroprotection is expressed as the percentage to reach the control value (100%), from the untreated ischemic neurons value (0%) (Table 1B). As shown, all the nitrones tested afforded values in all cases higher than the one determined for PBN (13.4 ± 1.9% at 5 mM) and NXY-059 (56.8 ± 2.5% at 250 μM), being remarkable for those observed for nitrones RP19 (87.5 ± 3.2% at 50 μM) and F2 (80.7 ± 2.7% at 5 μM). Next, transient global brain ischemia was performed on adult rats by the standard four-vessel occlusion model, in which carotid arteries are occluded during 15 min and 24 h after the irreversible occlusion of both vertebral arteries by electrocoagulation (Pulsinelli and Brierley, 1979; García-Bonilla et al., 2007). Ischemic animals were treated with RP19 and F2; NXY-059 diluted in 10% ethanol in saline as a vehicle by intraperitoneal injection when carotid arteries were un-clamped for reperfusion. Animals were studied after 5 days of reperfusion (R5d) after killing by transcardiac perfusion performed under deep anesthesia. Treatments were blindly and randomly performed and body temperature of 37°C was maintained (Table 1B). Cell death and apoptosis were assessed in the hippocampal cornu ammonis 1 (CA1) region and cerebral cortex (C). Nitrones RP19 and F2 showed higher inhibition of cell death than for NXY-059. In particular, best results were obtained with F2 at 0.1 mg/Kg concentration, and RP19 at 0.5 mg/Kg concentration. Apoptosis reduction by F2 (35% in hippocampal CA1, 91% in cortex, at 0.1 mg/kg concentration) and RP19 (38% in hippocampal CA1, 79% in cortex, at 0.5 mg/kg concentration) showed the best results, both higher than the values observed for NXY-059 (21% in hippocampal CA1, 55% in cortex), at the same concentration.

Table 1B.

In vitro antioxidant activity (A) and neuroprotection in neuronal cultures and in vivo model of ischemia (B).

| Nitrone | Cc | Neuroprotection (%) | Time after reperfusion | Cc | Cell death reduction (%) | Apoptosis reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBN | 5 mM | 13.4 ± 1.9 | ||||

| NXY-059 | 250 μM | 56.8 ± 2.5 | 5d | 40 mg/kg | 17 (CA1) 70 (C) | 21 (CA1) 55 (C) |

| RP19a | 10 μM | 70.9 ± 2.2 | 5d | 0.5 mg/kg | 35 (CA1)*** 63 (C)* | 38 (CA1)** 79 (C)* |

| 50 μM | 87.5 ± 3.2 | |||||

| F2b | 1 μM | 54.3 ± 1.3 | 5d | 0.05 mg/kg | 20 (CA1) 66 (C) | 30 (CA1)* 89 (C)* |

| 5 μM | 80.7 ± 2.7 | 5d | 0.1 mg/kg | 27 (CA1)** 83 (C)* | 35 (CA1)** 91 (C)* |

Concluding Remarks

In this Perspective article, we have updated the current neuroprotection studies and results for the development of melatonin and new nitrones for stroke. Regarding melatonin, the favorable in vitro and in vivo results reported, together with its great safety profile even at high concentrations, convert this indoleamine into an extraordinary therapeutic option to reduce the multiplicity of effects resulting from the brain ischemic cascade. Unfortunately, there is a lack of clinical studies with melatonin that confirm these results, maybe due to the lack of patentability of this molecule. The most recent results reported by Marco-Contelles’ group confirm that the neuroprotective strategy based on quinolylnitrones and cholesteronitrones have created great expectations that must still re-confirmed. These nitrones appear as promising agents due to robust antioxidant properties capable to target distinct steps of the biochemical pathways during and after the ischemic insult. Nonetheless, due to the preclinical results reviewed above, the use of melatonin or the new nitrones shown here, or better, multifunctional nitrones bearing the melatonin pharmacophoric motif, may rise as a potential tool to fight against brain ischemia injury and its multiple pathophysiological side-effects.

Author Contributions

AR and JM-C conceived the present “Perspective”. AR wrote the “melatonin” part, and JM-C wrote the “nitrone” section. MA and AA obtained the unpublished results shown in Table 1B corresponding to the global ischemia experiment of nitrone RP19. MJO-G and FL-M critically read and corrected the manuscript. AR, JM-C, MJO-G and FL-M approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

JM-C is indebted to Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (es) (MINECO) for grants SAF2012-33304, and SAF2015-65586-R. FL-M, MJO-G and JM-C thank Universidad Camilo José Cela (Project 2015-12 (NITROSTROKE)) for continued support.

References

- Alluri H., Wilson R. L., Anasooya Shaji C., Wiggins-Dohlvik K., Patel S., Liu Y., et al. (2016). Melatonin preserves blood-brain barrier integrity and permeability via matrix metalloproteinase-9 inhibition. PLoS One 11:e0154427. 10.1371/journal.pone.0154427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Alconada D., Alvarez A., Arteaga O., Martínez-Ibargüen A., Hilario E. (2013). Neuroprotective effect of melatonin: a novel therapy against perinatal hypoxia-ischemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 9379–9395. 10.3390/ijms14059379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrabi S. A., Sayeed I., Siemen D., Wolf G., Horn T. F. (2004). Direct inhibition of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore: a possible mechanism responsible for anti-apoptotic effects of melatonin. FASEB J. 18, 869–871. 10.1096/fj.03-1031fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayao M. S., Olaleyer O., Ihunwo A. O. (2010). Melatonin potentiates cells proliferation in the dentate gyrus following ischemic brain injury in adult rats. J. Animal. Vet Adv. 9, 1633–1638. 10.3923/javaa.2010.1633.1638 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayuso M. I., Chioua M., Martínez-Alonso E., Soriano E., Montaner J., Masjuán J., et al. (2015). CholesteroNitrones for stroke. J. Med. Chem. 58, 6704–6709. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balduini W., Carloni S., Perrone S., Bertrando S., Tataranno M. L., Negro S., et al. (2012). The use of melatonin in hypoxic-ischemic brain damage: an experimental study. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 25, 119–124. 10.3109/14767058.2012.663232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow-Walden L. R., Reiter R. J., Abe M., Pablos M., Menendez-Pelaez A., Chen L. D., et al. (1995). Melatonin stimulates brain glutathione peroxidase activity. Neurochem. Int. 26, 497–502. 10.1016/0197-0186(94)00154-m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brydon L., Roka F., Petit L., de Coppet P., Tissot M., Barrett P., et al. (1999). Dual signaling of human Mel1a melatonin receptors via Gi2, Gi3 and Gq/11 proteins. Mol. Endocrinol. 13, 2025–2038. 10.1210/me.13.12.2025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camello-Almaraz C., Gomez-Pinilla P. J., Pozo M. J., Camello P. J. (2008). Age-related alterations in Ca2+ signals and mitochondrial membrane potential in exocrine cells are prevented by melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 45, 191–198. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2008.00576.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carloni S., Albertini M. C., Galluzzi L., Buonocore G., Proietti F., Balduini W. (2014). Melatonin reduces endoplasmic reticulum stress and preserves sirtuin 1 expression in neuronal cells of newborn rats after hypoxia-ischemia. J. Pineal Res. 57, 192–199. 10.1111/jpi.12156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carloni S., Perrone S., Buonocore G., Longini M., Proietti F., Balduini W. (2008). Melatonin protects from the long-term consequences of a neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in rats. J. Pineal Res. 44, 157–164. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2007.00503.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan P. H. (2001). Reactive oxygen radicals in signaling and damage in the ischemic brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 21, 2–14. 10.1097/00004647-200101000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. Y., Chen T. Y., Lee M. Y., Chen S. T., Hsu Y. S., Kuo Y. L., et al. (2006). Melatonin decreases neurovascular oxidative/nitrosative damage and protects against early increases in the blood-brain barrier permeability after transient focal cerebral ischemia in mice. J. Pineal Res. 41, 175–182. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2006.00351.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T. Y., Lee M. Y., Chen H. Y., Kuo Y. L., Lin S. C., Wu T. S., et al. (2006). Melatonin attenuates the postischemic increase in blood-brain barrier permeability and decreases hemorrhagic transformation of tissue-plasminogen activator therapy following ischemic stroke in mice. J. Pineal Res. 40, 242–250. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2005.00307.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chern C. M., Liao J. F., Wang Y. H., Shen Y. C. (2012). Melatonin ameliorates neural function by promoting endogenous neurogenesis through the MT2 melatonin receptor in ischemic-stroke mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 52, 1634–1647. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chioua M., Sucunza D., Soriano E., Hadjipavlou-Litina D., Alcázar A., Ayuso I., et al. (2012). α-aryl-N-alkyl nitrones, as potential agents for stroke treatment: synthesis, theoretical calculations, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective and brain-blood barrier permeability properties. J. Med. Chem. 55, 153–168. 10.1021/jm201105a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi D. W. (1996). Ischemia-induced neuronal apoptosis. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 6, 667–672. 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80101-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S. Y., Han S. H. (2003). Melatonin attenuates kainic acid-induced hippocampal neurodegeneration and oxidative stress through microglial inhibition. J. Pineal Res. 34, 95–102. 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2003.00010.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa D. S., Martino T., Magalhaes F. C., Justo G., Coelho M. G., Barcellos J. C., et al. (2015). Synthesis of N-methylarylnitrones derived from alkyloxybenzaldehydes and antineoplastic effect on human cancer cell lines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 23, 2053–2061. 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A., McDowell M., Pava M. J., Smith J. A., Reiter R. J., Woodward J. J., et al. (2010). The inhibition of apoptosis by melatonin in VSC4.1 motoneurons exposed to oxidative stress, glutamate excitotoxicity, or TNF-α toxicity involves membrane melatonin receptors. J. Pineal Res. 48, 157–169. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2009.00739.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehouck M. P., Cecchelli R., Richard Green A., Renftel M., Lundquist S. (2002). In vitro blood-brain barrier permeability and cerebral endothelial cell uptake of the neuroprotective nitrone compound NXY-059 in normoxic, hypoxic and ischemic conditions. Brain Res. 955, 229–235. 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03469-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doggrell S. A. (2006). Nitrone spin on cerebral ischemia. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 7, 20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd R. A., Chandru H. K., He T., Towner R. (2011). Anti-cancer activity of nitrones and observations on mechanism of action. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 11, 373–379. 10.2174/187152011795677517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd R. A., Hensley K., Bing G. (2000). Evidence for enhanced neuro-inflammatory processes in neurodegenerative diseases and the action of nitrones as potential therapeutics. J. Neural Transm. Suppl. 60, 387–414. 10.1007/978-3-7091-6301-6_28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd R. A., Kopke R. D., Choi C. H., Foster S. B., Doblas S., Towner R. A. (2008). Nitrones as therapeutics. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 45, 1361–1374. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd R. A., Towner R. A., Wu D., Abbott A., Cranford R., Branch D., et al. (2010). Anti-cancer activity of nitrones in the Apc(Min/+) model of colorectal cancer. Free Radic. Res. 44, 108–117. 10.3109/10715760903321796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn R. W., MacWalter R. S., Doney A. S. (2008). The cost of cerebral ischaemia. Neuropharmacology 55, 250–256. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.05.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Bonilla L., Cid C., Alcázar A., Burda J., Ayuso I., Salinas M. (2007). Regulatory proteins of eukaryotic initiation factor 2-α subunit (eIF2 α) phosphatase, under ischemic reperfusion and tolerance. J. Neurochem. 103, 1368–1380. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04844.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelmers H. J., Gorter K., de Weerdt C. J., Wiezer H. J. (1988). A controlled trial of nimodipine in acute ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 318, 203–207. 10.1056/nejm198801283180402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godínez-Rubí M., Rojas-Mayorquín A. E., Ortuño-Sahagún D. (2013). Nitric oxide donors as neuroprotective agents after an ischemic stroke-related inflammatory reaction. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013:297357. 10.1155/2013/297357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong C. X., Iqbal K. (2008). Hyperphosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein tau: a promising therapeutic target for Alzheimer disease. Curr. Med. Chem. 15, 2321–2328. 10.2174/092986708785909111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossetete M., Phelps J., Arko L., Yonas H., Rosenberg G. A. (2009). Elevation of matrix metalloproteinases 3 and 9 in cerebrospinal fluid and blood in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Neurosurgery 65, 702–708. 10.1227/01.NEU.0000351768.11363.48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero J. M., Reiter R. J., Ortiz G. G., Pablos M. I., Sewerynek E., Chuang J. I. (1997). Melatonin prevents increases in neural nitric oxide and cyclic GMP production after transient brain ischemia and reperfusion in the Mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus). J. Pineal Res. 23, 24–31. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1997.tb00331.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta Y. K., Chaudhary G., Sinha K. (2002). Enhanced protection by melatonin and meloxicam combination in a middle cerebral artery occlusion model of acute ischemic stroke in rat. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 80, 210–217. 10.1139/y02-052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeland H. (2009). Neuroprotection by radical avoidance: search for suitable agents. Molecules 14, 5054–5102. 10.3390/molecules14125054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossmann K. A. (1994). Viability thresholds and the penumbra of focal ischemia. Ann. Neurol. 36, 557–565. 10.1002/ana.410360404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung Y. C., Chen T. Y., Lee E. J., Chen W. L., Huang S. Y., Lee W. T., et al. (2008). Melatonin decreases matrix metalloproteinase-9 activation and expression and attenuates reperfusion-induced hemorrhage following transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats. J. Pineal Res. 45, 459–467. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2008.00617.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C., Alexander M. (2001). Cerebral ischemia and inflammation. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 14, 89–94. 10.1097/00019052-200102000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue Y., Asanuma T., Smith N., Saunders D., Oblander J., Kotake Y., et al. (2007). Modulation of Fas-FasL related apoptosis by PBN in the early phases of choline deficient diet-mediated hepatocarcinogenesis in rats. Free Radic. Res. 41, 972–980. 10.1080/10715760701447322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H., Kanno I., Ibaraki M., Hatazawa J., Miura S. (2003). Changes in human cerebral blood flow and cerebral blood volume during hypercapnia and hypocapnia measured by positron emission tomography. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 23, 665–670. 10.1097/01.wcb.0000067721.64998.f5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilic E., Kilic U., Bacigaluppi M., Guo Z., Abdallah N. B., Wolfer D. P., et al. (2008). Delayed melatonin administration promotes neuronal survival, neurogenesis and motor recovery and attenuates hyperactivity and anxiety after mild focal cerebral ischemia in mice. J. Pineal Res. 45, 142–148. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2008.00568.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilic E., Kilic U., Reiter R. J., Bassetti C. L., Hermann D. M. (2004a). Prophylactic use of melatonin protects against focal cerebral ischemia in mice: role of endothelin converting enzyme-1. J. Pineal Res. 37, 247–251. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2004.00162.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilic E., Kilic U., Yulug B., Hermann D. M., Reiter R. J. (2004b). Melatonin reduces disseminate neuronal death after mild focal ischemia in mice via inhibition of caspase-3 and is suitable as an add-on treatment to tissue-plasminogen activator. J. Pineal Res. 36, 171–176. 10.1046/j.1600-079x.2003.00115.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilic U., Kilic E., Reiter R. J., Bassetti C. L., Hermann D. M. (2005). Signal transduction pathways involved in melatonin-induced neuroprotection after focal cerebral ischemia in mice. J. Pineal Res. 38, 67–71. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2004.00178.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. J., Kwon J. S. (1999). Effects of placing micro-implants of melatonin in striatum on oxidative stress and neuronal damage mediated by N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and non-NMDA receptors. Arch. Pharm. Res. 22, 35–43. 10.1007/bf02976433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. J., Lee S. R. (2014). Protective effect of melatonin against transient global cerebral ischemia-induced neuronal cell damage via inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Life Sci. 94, 8–16. 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh P. O. (2008a). Melatonin attenuates the cerebral ischemic injury via the MEK/ERK/p90RSK/bad signaling cascade. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 70, 1219–1223. 10.1292/jvms.70.1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh P. O. (2008b). Melatonin attenuates the focal cerebral ischemic injury by inhibiting the dissociation of pBad from 14–3-3. J. Pineal Res. 44, 101–106. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2007.00495.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh P. O. (2008c). Melatonin prevents the injury-induced decline of Akt/forkhead transcription factors phosphorylation. J. Pineal Res. 45, 199–203. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2008.00577.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh P. O. (2008d). Melatonin regulates nitric oxide synthase expression in ischemic brain injury. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 70, 747–750. 10.1292/jvms.70.747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh P. O. (2012a). Melatonin attenuates decrease of protein phosphatase 2A subunit B in ischemic brain injury. J. Pineal Res. 52, 57–61. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2011.00918.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh P. O. (2012b). Melatonin regulates the calcium-buffering proteins, parvalbumin and hippocalcin, in ischemic brain injury. J. Pineal Res. 53, 358–365. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2012.01005.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda S., Tsuchidate R., Smith M. L., Maples K. R., Siesjo B. K. (1999). Neuroprotective effects of a novel nitrone, NXY-059, after transient focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 19, 778–787. 10.1097/00004647-199907000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacoste B., Angeloni D., Dominguez-Lopez S., Calderoni S., Mauro A., Fraschini F., et al. (2015). Anatomical and cellular localization of melatonin MT1 and MT2 receptors in the adult rat brain. J. Pineal Res. 58, 397–417. 10.1111/jpi.12224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. Y., Kuan Y. H., Chen H. Y., Chen T. Y., Chen S. T., Huang C. C., et al. (2007). Intravenous administration of melatonin reduces the intracerebral cellular inflammatory response following transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats. J. Pineal Res. 42, 297–309. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2007.00420.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M., Lee S., Hong Y. (2014). Melatonin plus treadmill exercise synergistically promotes neurogenesis and reduce apoptosis in focal cerebral ischemic rats (877.17). FASEB J. 28. Supplement 877.17. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. M., Zipfel G. J., Choi D. W. (1999). The changing landscape of ischaemic brain injury mechanisms. Nature 399, A7–A14. 10.1038/399a007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling S., Sun Q., Li Y., Zhang L., Zhang P., Wang X., et al. (2012). CKIP-1 inhibits cardiac hypertrophy by regulating class II histone deacetylase phosphorylation through recruiting PP2A. Circulation 126, 3028–3040. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.102780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K., Gong C. X. (2005). Contributions of protein phosphatases PP1, PP2A, PP2B and PP5 to the regulation of tau phosphorylation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 22, 1942–1950. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04391.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo A. C., Chen A. Y., Hung V. K., Yaw L. P., Fung M. K., Ho M. C., et al. (2005). Endothelin-1 overexpression leads to further water accumulation and brain edema after middle cerebral artery occlusion via aquaporin 4 expression in astrocytic end-feet. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 25, 998–1011. 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo E. H., Moskowitz M. A., Jacobs T. P. (2005). Exciting, radical, suicidal: how brain cells die after stroke. Stroke 36, 189–192. 10.1161/01.STR.0000153069.96296.fd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod M. R., van der Worp H. B., Sena E. S., Howells D. W., Dirnagl U., Donnan G. A. (2008). Evidence for the efficacy of NXY-059 in experimental focal cerebral ischaemia is confounded by study quality. Stroke 39, 2824–2829. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.515957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchester L. C., Coto-Montes A., Boga J. A., Andersen L. P., Zhou Z., Galano A., et al. (2015). Melatonin: an ancient molecule that makes oxygen metabolically tolerable. J. Pineal Res. 59, 403–419. 10.1111/jpi.12267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandavia C., Sowers J. R. (2012). Phosphoprotein phosphatase PP2A regulation of insulin receptor substrate 1 and insulin metabolic signaling. Cardiorenal Med. 2, 308–313. 10.1159/000343889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manev H., Uz T., Kharlamov A., Joo J. Y. (1996). Increased brain damage after stroke or excitotoxic seizures in melatonin-deficient rats. FASEB J. 10, 1546–1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers C. D., Boerma T., Ma Fat D. (2009). Global and regional causes of death. Br. Med. Bull. 92, 7–32. 10.1093/bmb/ldp028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matias A. C., Biazolla G., Cerchiaro G., Keppler A. T. (2016). α-Aryl-N-aryl nitrones: synthesis and screening of a new scaffold for cellular protection against an oxidative toxic stimulus. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 24, 232–239. 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaner J., Alvarez-Sabin J., Molina C. A., Anglés A., Abilleira S., Arenillas J., et al. (2001). Matrix metalloproteinase expression is related to hemorrhagic transformation after cardioembolic stroke. Stroke 32, 2762–2767. 10.1161/hs1201.99512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti R., Zanin A., Pansiot J., Spiri D., Manganozzi L., Kratzer I., et al. (2015). Melatonin reduces excitotoxic blood-brain barrier breakdown in neonatal rats. Neuroscience 311, 382–397. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.10.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niizuma K., Yoshioka H., Chen H., Kim G. S., Jung J. E., Katsu M., et al. (2010). Mitochondrial and apoptotic neuronal death signaling pathways in cerebral ischemia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1802, 92–99. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novelli G. P., Angiolini P., Tani R., Consales G., Bordi L. (1986). Phenyl-T-butyl-nitrone is active against traumatic shock in rats. Free Radic. Res. Commun. 1, 321–327. 10.3109/10715768609080971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozacmak V. H., Barut F., Ozacmak H. S. (2009). Melatonin provides neuroprotection by reducing oxidative stress and HSP70 expression during chronic cerebral hypoperfusion in ovariectomized rats. J. Pineal Res. 47, 156–163. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2009.00695.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozyener F., Çetinkaya M., Alkan T., Gören B., Kafa I. M., Kurt M. A., et al. (2012). Neuroprotective effects of melatonin administered alone or in combination with topiramate in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic rat model. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 30, 435–444. 10.3233/RNN-2012-120217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parada E., Buendia I., León R., Negredo P., Romero A., Cuadrado A., et al. (2014). Neuroprotective effect of melatonin against ischemia is partially mediated by α-7 nicotinic receptor modulation and HO-1 overexpression. J. Pineal Res. 56, 204–212. 10.1111/jpi.12113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes S. D., Rancan L., Kireev R., González A., Louzao P., González P., et al. (2015). Melatonin counteracts at a transcriptional level the inflammatory and apoptotic response secondary to ischemic brain injury induced by middle cerebral artery blockade in aging rats. Biores. Open Access 4, 407–416. 10.1089/biores.2015.0032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschen W. (2000). Role of calcium in neuronal cell injury: which subcellular compartment is involved? Brain Res. Bull. 53, 409–413. 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00369-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patiño P., Parada E., Farré-Alins V., Molz S., Cacabelos R., Marco-Contelles J., et al. (2016). Melatonin protects against oxygen and glucose deprivation by decreasing extracellular glutamate and Nox-derived ROS in rat hippocampal slices. Neurotoxicology 57, 61–68. 10.1016/j.neuro.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson G., Robinson F., Beers Gibson T., Xu B. E., Karandikar M., Berman K., et al. (2001). Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: regulation and physiological functions. Endocr. Rev. 22, 153–183. 10.1210/er.22.2.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei Z., Cheung R. T. (2004). Pretreatment with melatonin exerts anti-inflammatory effects against ischemia/reperfusion injury in a rat middle cerebral artery occlusion stroke model. J. Pineal Res. 37, 85–91. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2004.00138.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei Z., Fung P. C. W., Cheung R. T. F. (2003). Melatonin reduces nitric oxide level during ischemia but not blood-brain barrier breakdown during reperfusion in a rat middle cerebral artery occlusion stroke model. J. Pineal Res. 34, 110–118. 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2003.00014.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulsinelli W. A., Brierley J. B. (1979). A new model of bilateral hemispheric ischemia in the unanesthetized rat. Stroke 10, 267–272. 10.1161/01.str.10.3.267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter R. J., Paredes S. D., Manchester L. C., Tan D. X. (2009). Reducing oxidative/nitrosative stress: a newly-discovered genre for melatonin. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 44, 175–200. 10.1080/10409230903044914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter R. J., Tan D. X., Manchester L. C., Pilar Terron M., Flores L. J., Koppisepi S. (2007). Medical implications of melatonin: receptor-mediated and receptor-independent actions. Adv. Med. Sci. 52, 11–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C., Mayo J. C., Sainz R. M., Antolín I., Herrera F., Martín V., et al. (2004). Regulation of antioxidant enzymes: a significant role for melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 36, 1–9. 10.1046/j.1600-079x.2003.00092.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh J.-K., Jung K.-H., Chu K. (2008). Adult stem cell transplantation in stroke: its limitations and prospects. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 3, 185–196. 10.2174/157488808785740352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman S. M., Olney J. W. (1986). Glutamate and the pathophysiology of hypoxic—ischemic brain damage. Ann. Neurol. 19, 105–111. 10.1002/ana.410190202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruediger R., Pham H. T., Walter G. (2001). Disruption of protein phosphatase 2A subunit interaction in human cancers with mutations in the Aα subunit gene. Oncogene 12, 10–15. 10.1038/sj.onc.1204059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah F. A., Park D. J., Gim S. A., Koh P. O. (2015). Curcumin treatment recovery the decrease of protein phosphatase 2A subunit B induced by focal cerebral ischemia in Sprague-Dawley rats. Lab. Anim. Res. 31, 134–138. 10.5625/lar.2015.31.3.134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signorini C., Ciccoli L., Leoncini S., Carloni S., Perrone S., Comporti M., et al. (2009). Free iron, total F2-isoprostanes and total F4-neuroprostanes in a model of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: neuroprotective effect of melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 46, 148–154. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2008.00639.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha K., Degaonkar M. N., Jagannathan N. R., Gupta Y. K. (2001). Effect of melatonin on ischemia reperfusion injury induced by middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 428, 185–192. 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01253-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slominski R. M., Reiter R. J., Schlabritz-Loutsevitch N., Ostrom R. S., Slominski A. T. (2012). Melatonin membrane receptors in peripheral tissues: distribution and functions. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 351, 152–166. 10.1016/j.mce.2012.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J., Kang S. M., Lee W. T., Park K. A., Lee K. M., Lee J. E. (2014). The beneficial effect of melatonin in brain endothelial cells against oxygen-glucose deprivation followed by reperfusion-induced injury. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2014:639531. 10.1155/2014/639531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontag E., Luangpirom A., Hladik C., Mudrak I., Ogris E., Speciale S., et al. (2004). Altered expression levels of the protein phosphatase 2A ABαC enzyme are associated with Alzheimer disease pathology. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 63, 287–301. 10.1093/jnen/63.4.287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F.-Y., Lin X., Mao L.-Z., Ge W.-H., Zhang L.-M., Huang Y. L., et al. (2002). Neuroprotection by melatonin against ischemic neuronal injury associated with modulation of DNA damage and repair in the rat following a transient cerebral ischemia. J. Pineal Res. 33, 48–56. 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2002.01891.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y., Cai B., Yuan F., He X., Lin X., Wang J., et al. (2014). Melatonin pretreatment improves the survival and function of transplanted mesenchymal stem cells after focal cerebral ischemia. Cell Transplant. 23, 1279–1291. 10.3727/096368913x667510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan D. X., Manchester L. C., Terron M. P., Flores L. J., Tamura H., Reiter R. J. (2007). Melatonin as a naturally occurring co-substrate of quinone reductase-2, the putative MT3 melatonin membrane receptor: hypothesis and significance. J. Pineal Res. 43, 317–320. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2007.00513.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toklu H., Deniz M., Keyer-Uysal M., Sener G. (2009). The protective effect of melatonin and amlodipine against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion-induced oxidative brain injury in rats. Marmara Med. J. 22, 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wakatsuki A., Okatani Y., Shinohara K., Ikenoue N., Fukaya T. (2001). Melatonin protects against ischemia/reperfusion-induced oxidative damage to mitochondria in fetal rat brain. J. Pineal Res. 31, 167–172. 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2001.310211.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Duan W., Li Y., Yan J., Yi W., Liang Z., et al. (2013). New role of silent information regulator 1 in cerebral ischemia. Neurobiol. Aging 34, 2879–2888. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Jiang S., Dong Y., Fan C., Zhao L., Yang X., et al. (2015). Melatonin prevents cell death and mitochondrial dysfunction via a SIRT1-dependent mechanism during ischemic-stroke in mice. J. Pineal Res. 58, 61–70. 10.1111/jpi.12193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., An R., Yang Y., Yang X., Liu H., Yue L., et al. (2015). Melatonin alleviates brain injury in mice subjected to cecal ligation and puncture via attenuating inflammation, apoptosis and oxidative stress: the role of SIRT1 signaling. J. Pineal Res. 59, 230–239. 10.1111/jpi.12254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zivin J. A., Fisher M., DeGirolami U., Hemenway C. C., Stashak J. A. (1985). Tissue plasminogen activator reduces neurological damage after cerebral embolism. Science 230, 1289–1292. 10.1126/science.3934754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]