Highlights

-

•

The first reported case of a rectal GIST with metastasis to the penis is documented by this report.

-

•

The primary cancer was treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and abdominoperineal resection.

-

•

Biopsies of lesions identified on follow-up imaging were consistent with metastatic GIST.

-

•

Metastasectomy and adjuvant chemotherapy have been utilized to help prolong survival.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), Rectal, Metastasis, Penile

Abstract

We report the case of a 51-year-old gentleman with previously diagnosed gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) of the rectum with metastasis to the penis. The patient underwent abdominoperineal resection of the primary tumor with negative margins and completed a three-year course of imatinib mesylate (Gleevec). Forty months after resection of his rectal tumor, the patient presented to his urologist with worsening testicular pain, mild lower urinary tract obstructive symptoms, and nocturia. A pelvic MRI revealed the presence of an ill-defined mass in the right perineum extending from the base of the penis to the penoscrotal junction. Biopsy of this mass was consistent with metastatic GIST. To our knowledge, this is the first report of metastatic GIST to the penis.

1. Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are mesenchymal neoplasms that account for approximately 1–3% of all malignant gastrointestinal tumors [1]. Clinical characteristics of the tumor are dependent on the anatomic location, size, and aggressiveness of the tumor. Primary GISTs originate most commonly in the stomach [2], but primary GISTs arising from the pleura, retroperitoneum, omentum, and mesentery have also been reported [3]. GISTs typically metastasize to intra-abdominal locations, with common metastatic sites being the liver, omentum, and the peritoneal cavity [4]. Metastasis of GISTs to lymph nodes and extra-abdominal sites via lymphatics is rare [5].

Imatinb mesylate (Gleevec) has proven to be a safe and efficacious adjunct in the treatment of KIT (CD117)-positive GISTs and has been used for the last 15 years for the treatment of metastatic GISTs [6], [7]. A literature review of the metastatic potential of GISTs identified one case of a “lump at the base of the penis” thought to be a metastatic lesion arising from a primary rectal tumor [8]. Although there have been no reported cases of metastatic GIST to the corpora of the penis, cases of GIST metastases to the prostate from primary rectal tumors are documented [9], [10], [11]. In this report, we describe the first documented case of metastatic GIST to the penis.

2. Presentation of case

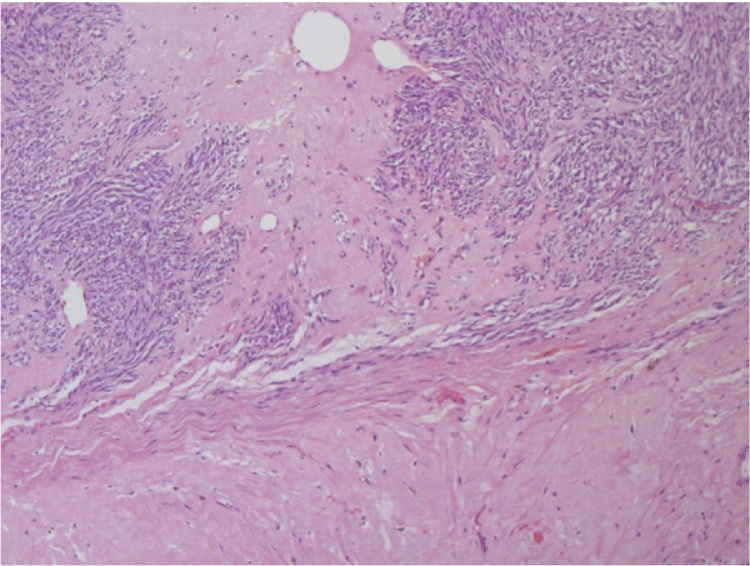

A 51-year-old Caucasian male was found to have a 6.5 × 6 cm rectal mass just proximal to the sphincter complex on screening colonoscopy. Biopsy of the mass demonstrated GIST with mitotic figures. The patient was started on neoadjuvant imatinib therapy to downstage the tumor prior to surgical resection. Four months after initiating treatment, an MRI of the pelvis revealed excellent response to imatinib, as the rectal mass had reduced in size to 3.8 × 3.1 × 2.2 cm. After a total of eight months of neoadjuvant imatinib therapy, the patient underwent an abdominoperineal resection (APR). The patient did well peri-operatively. Pathology of the surgical specimen revealed a gastrointestinal stromal tumor 2.8 cm in greatest extent, 80–90% hyalinization with scarce cellularity (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). The lesion involved the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and perirectal soft tissue. Mitotic rate of <1/50hpf was visualized. Perineural invasion was identified, but lymphovascular invasion was not. Negative margins were attained, and eleven of eleven lymph nodes collected were negative for malignancy. Imatinib therapy was continued postoperatively.

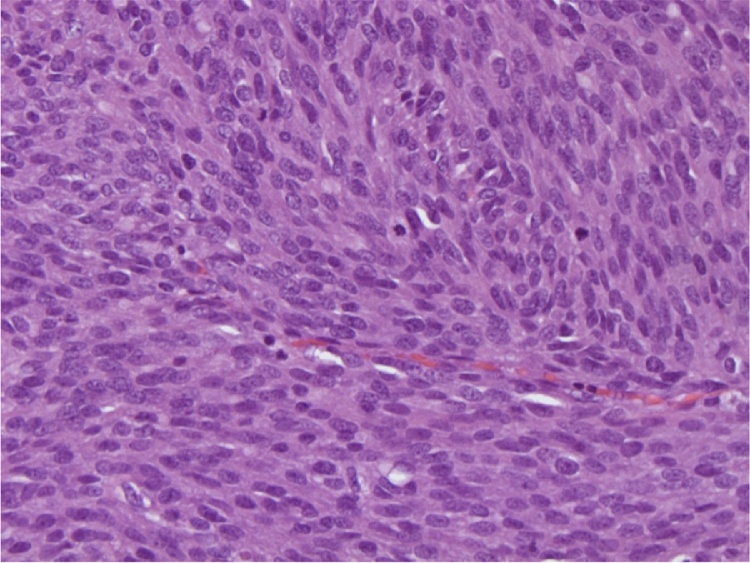

Fig. 1.

Microscopic analysis of the rectal GIST. Tumor cells are spindled, forming fascicles with increased mitotic rate.

Fig. 2.

Microscopic analysis of the rectal GIST. The tumor demonstrates large areas of hyalinization secondary to therapy with imatinib.

One year after APR, a surveillance colonoscopy was performed, and no recurrent or metachronous lesions were found. The patient was followed with imaging studies every six months. CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis obtained over following three years revealed no evidence of intra-abdominal or pelvis abnormalities or evidence of recurrent or metastatic disease. Imatinib was discontinued after a total of three years of treatment.

Three and a half years after APR, the patient presented with complaints of obstructive urinary symptoms, erectile dysfunction, and progressively worsening testicular pain radiating towards his rectum. A physical examination identified no gross lesions of the penis. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was unremarkable, and cystoscopy showed no evidence of obstruction or abnormality of the urethra or bladder. The patient was treated for suspected epididymitis vs. prostatitis.

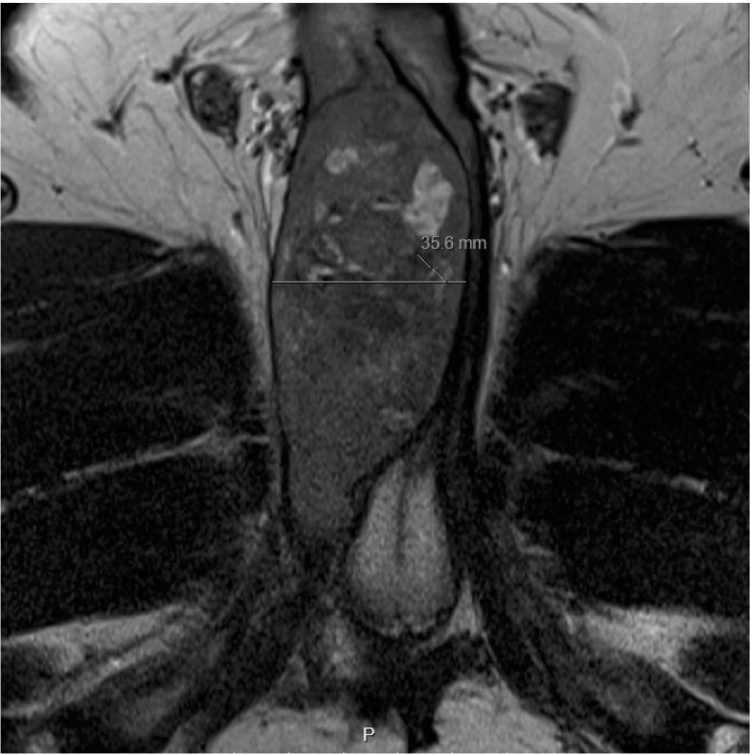

The patient continued to experience worsening right testicular, right hip, and perineal pain, which was moderately relieved by application of a heating pad and sitz baths but not by narcotic pain medication. On examination, the proximal penile shaft was tender to palpation, and an ill-defined mass was noted in the right perineum extending from the base of the penis to the penoscrotal junction. A pelvic MRI revealed an 8.4 × 4.3 × 3.6 cm enhancing mass in the right corpus cavernosum (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). The patient was referred to Urologic Oncology. Needle biopsies of the penile lesion were obtained, and histologic evaluation of these specimens revealed a cellular spindle cell tumor with mitoses, positive CD117 immunostain, and negative for desmin, findings which are consistent with metastatic GIST.

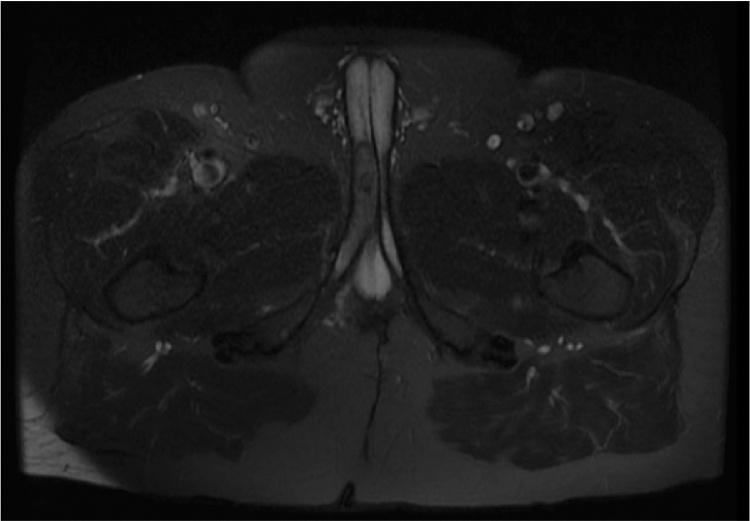

Fig. 3.

Axial view of pelvis MRI. Axial view of the pelvis on MRI revealed a right corpus cavernosum mass.

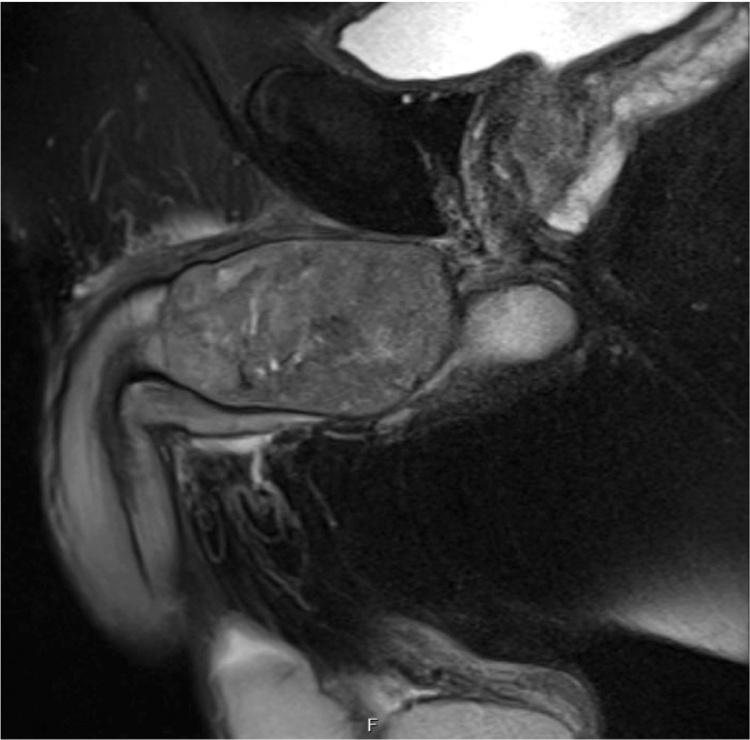

Fig. 4.

Sagittal view of pelvis MRI. MRI of the pelvis demonstrated the right corpus cavernosum mass causing external compression of the urethra, leading to the patient’s lower urinary tract obstructive symptoms.

Medical and surgical options were discussed with the patient, who opted to continue imatinib therapy, as opposed to undergoing surgery. Three months after resuming imatinib, the patient reported decreased perineal pain and ability to obtain an erection with the use of a vacuum device. Four months after resuming imatinib, an MRI of the pelvis demonstrated that the metastatic penile lesion had decreased in size (Fig. 5). The patient was then receptive to undergo surgical resection of the right corpus cavernosum. Pathological examination of the excised tumor revealed metastatic GIST with lymphovascular invasion identified, 94 mitoses/50hpf, and positive margins. Imatinib was continued post-operatively.

Fig. 5.

Axial view of follow-up MRI. MRI of the pelvis obtained four months after resuming imatinib demonstrated decrease in the size of the right corpus cavernosum mass from 8.4 × 4.3 × 3.6 cm to 4.9 × 1.8 × 1.5 cm.

One month after corpus cavernosum resection, the patient began to experience worsening positional right hip pain that radiated to his right knee. Despite continued use of imatinib, repeat MRI of the pelvis three months after metasetectomy demonstrated lesions within the left corpus cavernosum concerning for persistent metastatic disease. Sunitinib was substituted for imatinib at that time. An MRI of the pelvis obtained six months after metastectomy demonstrated further progression in the number and size of the lesions within the left corpus cavernosum, as well as a lesion in the right ischium concerning for osseous metastasis. Core biopsy of the right ischial lesion was consistent with a poorly differentiated metastatic carcinoma. The malignant cells were strongly positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, but negative for Ckit (CD 117) and S-100. Further analysis of the biopsy sample revealed that the lesion contained an exon 11 mutation, suggesting that the lesion was consistent with metastatic GIST to the right ischium. PET CT imaging also identified tumor in the left ischiorectal fossa. Transitioning from sunitinib to regorafenib was recommended.

3. Discussion

For patients presenting with metastatic GIST, the median survival is reported to be 19 months [12]. The treatment of metastatic GIST depends on the size, location, and extent of the metastatic lesions and may incorporate both medical and surgical intervention. First-line medical treatment with imatinib for patients with metastatic GIST yields regression or stabilization of disease in ∼80% of patients [13]. However, despite the initial response to imatinib seen in most patients with metastatic GIST, a significant portion of them develop acquired resistance to imatinib, with a median time to resistance of two years. Patients with metastatic GIST treated with imatinib have a median overall survival of five years [14].

In a phase III randomized controlled trial, Demetri et al. found that patients with advanced GIST resistant or intolerant to imatinib treated with sunitinib experienced a longer median time to progression (27.3 weeks vs. 6.4 weeks), longer progression-free survival (24.1 weeks vs. 6.0 weeks), and improved overall survival compared to the placebo group [15].

In a multicenter, randomized placebo-controlled trial in which patients with progression of metastatic colorectal cancer despite receiving standard therapy, Grothey et al. found that patients who received regorafenib had a median overall survival of 6.4 months compared to 5.0 months in the placebo group [16]. Adverse events attributable to regorafenib include hand-foot skin reaction, fatigue, diarrhea, hypertension, and rash, anorexia, and mucositis [16], [17]. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 199 patients with advanced GIST and failure of imatinib and sunitinib to control disease, the GRID trial found that patients who received regorafenib had a longer median progression-free survival compared to patients who received a placebo (4.8 months vs. 0.9 months), and 75.9% were found to have partial response or stable disease while on regorafenib [18]. George et al. similarly found that patients with metastatic GIST who were started on regorafenib had a median progress-free survival of 10.0 months. Twenty-six of 33 patients with metastatic GIST that failed treatment with imatinib and sunitinib were found to have partial response (four patients) or stable disease (22 patients) after at least two cycles of regorafenib [19].

A retrospective study examining surgical resection in patients with metastatic GIST concluded that survival in patients who underwent metastasectomy was associated with disease responsiveness while on imatinib therapy. Patients with disease that remained stable or responded to imatinib treatment were found to have prolonged overall survival after undergoing metastasectomy [13].

4. Conclusion

This case documents the first reported case of a GIST with metastasis to the penis. The patient presented in this case report was found to have a rectal GIST on screening colonoscopy. This lesion subsequently has been found to metastasize to the penis and right hip. Analysis of biopsies of these lesions demonstrates an exon 11 activating KIT mutation. Heinrich et al. evaluated 127 patients diagnosed with GISTs for mutations of KIT or PDGFRA and correlated the patients’ mutation type to their respective clinical outcome. Patients with an exon 11 activating mutation of KIT were found to have a higher partial response rate to imatinib (83.5% vs. 47.8%) and overall survival (p = 0.0034) compared to patients with exon 9 KIT mutations [20]. Partial response to imatinib was initially seen in both the primary GIST and corpus cavernosum metastatic lesion of the patient described here. Despite continued use of imatinib, metastatectomy, and treatment with sunitinib, the patient has unfortunately experienced progression of his metastatic disease. Patients with primary GIST who underwent complete resection are reported to have a median survival of 66 months [12]. Due to the progression of our patient’s metastatic disease despite treatment with imatinib and sunitinib, treatment with regorafenib has been recommended.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding Source

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Submission declaration

This report is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. Its publication is approved by all authors and the subject of the report. If accepted, it will not be published elsewhere including electronically in the same form, in English or in any other language, without the written consent of the copyright-holder.

Contributors

Dr. Carlson, Dr. Mizell, and medical student Wilson Alobuia each contributed to the writing of this article, its editing, and preparation for submission.

Ethical approval

Consent was obtained from the subject of this report.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Dr. Carlson and Wilson Alobuia participated in the literature review and writing of this report. Dr. Mizell contributed by serving as an expert in the field of Colorectal Surgery and in the writing and editing of this report. Each of the authors participated in the final preparation of this report for submission.

Guarantor

Jacob Carlson.

Acknowledgment

Rodney Davis, MD, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Chairman, Department of Urology.

Contributor Information

Jacob Carlson, Email: jcarlson@uams.edu, JCarlson@uams.edu.

Wilson Alobuia, Email: WMAlobuia@uams.edu.

Jason Mizell, Email: JSMizell@uams.edu.

References

- 1.Cassier P., Ducimetière F., Lurkin A. A prospective epidemiological study of new incident GISTs during two consecutive years in Rhône Alpes region: incidence and molecular distribution of GIST in a European region. Br. J. Cancer. 2010;103(2):165–170. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macías-García L., De La Hoz-Herazo H., Robles-Frías A. Collision tumour involving a rectal gastrointestinal stromal tumour with invasion of the prostate and a prostatic adenocarcinoma. Diagn. Pathol. 2012;7(1):150. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-7-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reith J., Goldblum J., Lyles R. Extragastrointestinal (soft tissue) stromal tumors: an analysis of 48 cases with emphasis on histologic predictors of outcome. Mod. Pathol. 2000;13(5):577–585. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dematteo R. The GIST of targeted cancer therapy: a tumor (gastrointestinal stromal tumor), a mutated gene (c-kit), and a molecular inhibitor (STI571) Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2002;9(9):831–839. doi: 10.1007/BF02557518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamba G., Gupta R., Lee B. Current management and prognostic features for gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2012;1(1):14. doi: 10.1186/2162-3619-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ami E., Demetri G.A. Safety evaluation of imatinib mesylate in the treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2016;15(4):571–578. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2016.1152258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel S. Long-term efficacy of imatinib for treatment of metastatic GIST. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2013;72(2):277–286. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vij M., Agrawal V., Kumar A. Cytomorphology of gastrointestinal stromal tumors and extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a comprehensive morphologic study. J. Cytol. 2013;30(1):8–12. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.107505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reinke D., Deisch J., Reinke D. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor with an unusual presentation as an enlarged prostate gland: a case report and review of the literature. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2016;7:71–74. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2015.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee C., Lin Y., Lin H. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the prostate: a case report and literature review. Hum. Pathol. 2006;37(10):1361–1365. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anagnostou E., Miliaras D., Panagiotakopoulos V. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) on transurethral resection of the prostate: a case report and review of the literature. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2011;19(5):632–636. doi: 10.1177/1066896911408304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dematteo R., Lewis J., Leung D. Two hundred gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann. Surg. 2000;231(1):51–58. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200001000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bamboat Z., Dematteo R. Metastasectomy for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J. Surg. Oncol. 2013;109(1):23–27. doi: 10.1002/jso.23451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blanke C., Demetri G., Mehren M. Long-term results from a randomized phase II trial of standard- versus higher-dose imatinib mesylate for patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing KIT. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26(4):620–625. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.4403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demetri G., Van Oosterom A., Garrett C. Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1329–1338. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grothey A., Van Cutsem E., Sobrero A. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:303–312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61900-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Komatsu Y., Doi T., Sawaki A. Regorafenib for advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors following imatinib and sunitinib treatment: a subgroup analysis evaluating japanese patients in the phase III GRID trial. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015;20(5):905–912. doi: 10.1007/s10147-015-0790-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demetri G., Reichardt P., Kang Y. Efficacy and safety of regorafenib for advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours after failure of imatinib and sunitinib (GRID): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:295–302. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61857-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.George S., Wang Q., Heinrich M. Efficacy and safety of regorafenib in patients with metastatic and/or unresectable GI stromal tumor after failure of imatinib and sunitinib: a multicenter phase II trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30(18):2401–2407. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.9394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heinrich M. Kinase mutations and imatinib response in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21(23):4342–4349. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]