Abstract

The recent discovery of the CRISPR/Cas system and repurposing of this technology to edit a variety of different genomes have revolutionized an array of scientific fields, from genetics and translational research, to agriculture and bioproduction. In particular, the prospect of rapid and precise genome editing in laboratory animals by CRISPR/Cas has generated an immense interest in the scientific community. Here we review current in vivo applications of CRISPR/Cas and how this technology can improve our knowledge of gene function and our understanding of biological processes in animal models.

Keywords: cancer, CRISPR/Cas9, disease models, genome editing, mouse models

Introduction

Initially identified as a component of a bacterial immune system, CRISPR/Cas provides a fast and flexible tool for efficient sequence-specific genome editing. The central mechanism of CRISPR/Cas editing is an RNA ‘guide’ that targets the CRISPR-associated (Cas) nuclease to a specific stretch of DNA sequence by complementary binding [1]. In the type II CRISPR system, a single Cas protein, Cas9, forms a complex with the CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and a trans-activating RNA (tracrRNA) (reviewed in [2]). Work from the Doudna, Zhang and Church and Charpentier groups has demonstrated that the two RNAs can be fused into a chimeric single synthetic guide RNA (sgRNA). This sgRNA can be engineered to target a 17–20 base pair stretch of DNA sequence preceding a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), and achieves efficient cutting in eukaryotic cells in vitro and in vivo [1,3,4]. Repair of the cleaved DNA by nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) introduces random mutations into the cleaved site, while homology-directed repair (HDR) employs a homologous DNA template to introduce specific ‘knock-in’ sequences, as in traditional homologous recombination.

Although other programmable nucleases such as zinc-finger nucleases and transcription activator-like nucleases (TALENs) can successfully be used to edit the genome for similar applications [5], challenges in design and production of these engineered proteins have limited their widespread use. In contrast, the RNA-based mechanism of target recognition in the CRISPR/Cas system makes gene editing dramatically easier and cheaper, as it allows researchers to rationally design and produce many sgRNAs in parallel. The ability to use a single Cas9 protein with the different sgRNAs further opens the door to multiplexed and combinatorial gene editing. Moreover, discovery of different Cas9 variants as well as generation of several Cas9-fusion proteins expands rapidly the CRISPR/Cas toolkit. The surge of excitement surrounding CRISPR parallels that surrounding the development of RNA interference technology at the turn of the last century, which quickly changed the way we study gene function. As was with the early days of RNAi, many groups are still working to develop and optimize new CRISPR tools. Already now, the CRISPR system presents a powerful tool adding to our arsenal for modeling disease and studying gene function in vivo. Together with established approaches for spatiotemporal control over gene activity and delivery, CRISPR/Cas enables modeling of inherited diseases, which are passed through the germline, as well as sporadic diseases that occur as a result of mutations in somatic tissue [6,7]. Here we summarize current advances in applying CRISPR technology to mouse models of human disease.

Rapid development of germline animal models with CRISPR/Cas9

Genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) have been an essential resource for modeling human disease and studying gene function for more than three decades. The technology to manipulate the mouse genome has evolved substantially over this time, from random mutagenesis with DNA-damaging compounds to transgene overexpression and homologous recombination [7].

Embryonic stem (ES) cells targeted by homologous recombination (HR) can be injected into a wild-type host blastocyst and can contribute to the germline of the resulting chimeric animals to produce strains of knockout or knock-in mice [8]. While early GEMMs were limited to constitutive, whole-body mutations, the advent of Cre–loxP and tetracycline-inducible technologies enabled the development of more sophisticated models incorporating tissue-specific and inducible genetic manipulation [9,10]. By enabling researchers to engineer the genome with unprecedented ease and efficiency, gene editing via site-specific nucleases now represents the next phase of GEMM development.

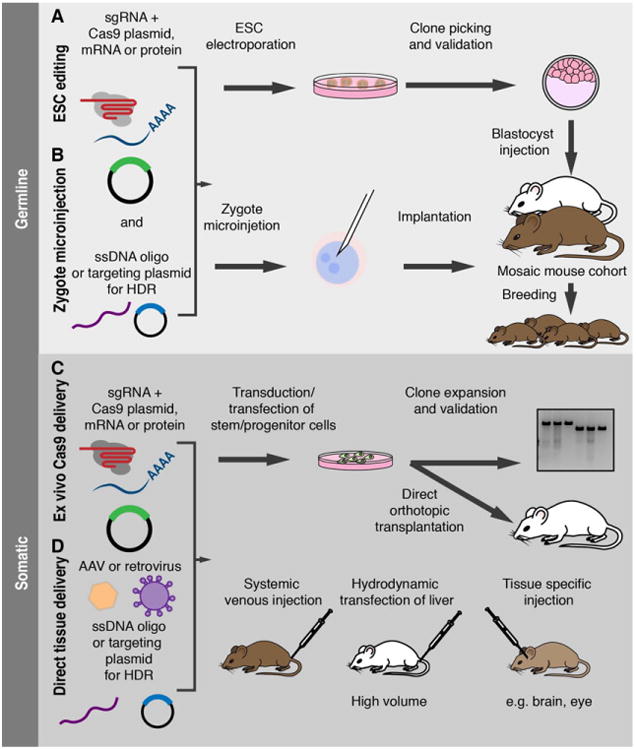

Traditional gene targeting depends on the occurrence of random double-strand breaks at the gene of interest, and their repair using a homologous template. The low frequency of such breaks occurring at the locus of interest makes this process inefficient. CRISPR/Cas and other site-specific nucleases dramatically increase the efficiency of this process by inducing double-strand breaks at the intended loci. After the initial studies demonstrated CRISPR/Cas activity in mammalian cells, the prospect of using this technology to accelerate the GEMM production generated enormous enthusiasm in the scientific community. Indeed, within months of the initial publications describing use of CRISPR/Cas genome editing, Jaenisch and colleagues showed efficient multiplex disruption of up to five genes in mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells [11]. By cotransfecting plasmid vectors carrying both Cas9 and an sgRNA into the ES cells (Fig. 1), the authors were able to isolate clones carrying different combinations of loss-of-function mutations induced by imprecise NHEJ with an efficiency of 65–81%. A similar approach has been used to generate mice with mutations in the Bcl11a enhancer in order to characterize the enhancer function in vivo [12].

Fig. 1.

Summary of in vivo CRISPR strategies for mouse model production. Upper panel: generation of germline models with CRISPR/Cas. CRISPR-edited mouse models can be produced via electroporation of ES cells (A), or by direct injection of Cas9 and the appropriate sgRNA into zygotes at the single-cell stage (B). In either strategy, Cas9 may be introduced in the form of a DNA plasmid, transcribed mRNA, or translated as a protein to reduce the duration of Cas9 activity. Concomitant addition of a short ssDNA template or a dsDNA plasmid with 1–3 kb homology arms allows for insertion of specific point mutations and large insertions/deletions, respectively, via HDR. In the ES cell approach, individual ES clones can be expanded and validated prior to injection into blastocysts and implantation. The resulting founders are chimeras, derived from both the injected ES cells and host blastocyst. Animals derived from zygote injection may be somatic mosaics, carrying distinct mutations in different cells. In both cases, the founders are then bred to establish a stable mutant line. Lower panel: in vivo somatic cell editing with CRISPR/Cas. Cas9 can be delivered to primary stem/progenitor cells in culture via transient transfection or in retro-or lentiviral vector also carrying the sgRNA (C). Edited cells can then be expanded and transplanted. CRISPR components can be delivered directly to somatic cells (D) via local or systemic injection, or specifically to the liver via hydrodynamic transfection.

Another study showed successful HDR-mediated gene targeting in mouse ES cells following coelectroporation of Cas9, sgRNA, and donor plasmids [13]. The inclusion of a selectable marker into the donor sequence also enables efficient recovery of targeted clones [14]. Indeed, the advantage of ES cell targeting with Cas9 lies in the ability to rapidly isolate and characterize precise mutations in individual clones in order to select the optimal candidates for mouse production. Like standard HR, this approach can be used to generate conditional alleles and insert reporter genes or epitope tags. The development of new strategies, such as reporters of HDR activity, will likely continue to improve the efficiency of precision gene editing via CRISPR in ES cells [15].

In addition to generating constitutive mutations via transient Cas9 transfection in ES cells, CRISPR/Cas can be integrated into doxycycline-regulatable systems to allow for spatiotemporal control over gene editing. Introduction of a doxycycline-inducible construct carrying Cas9 and one or more sgRNAs into mouse ES cells harboring a reverse tetracycline transactivator (rtTA), followed by blastocyst injection produces chimeras with inducible Cas9 editing in tissues where the rtTA is expressed [16]. This system also allows for transient expression of Cas9 to limit potential off-target cutting or toxicity.

The major drawback of generating mice via CRISPR/Cas editing in ES cells relates to the challenge of ES cell culture, which requires specialized media and experience. Not all laboratories and institutions have access to ES cell resources for routine mouse production in this manner. Additionally, mouse strains vary in their ability to produce robust ES cells that contribute to the germline of chimeric mice. Although ES cell culture methods are constantly improving, multiple rounds of backcrossing may be required to generate mice on a particular background.

An alternative method to rapidly produce new mouse mutants is directly editing the genome with CRISPR/Cas in zygotes at the pronuclear stage (Fig. 1). This has been successfully achieved with other site-specific nucleases [17]. In the same study that demonstrated efficient CRISPR/Cas9 editing in ES cells, Jaenisch and colleagues showed that simply coinjecting in vitro transcribed Cas9 mRNA and sgRNAs targeting Tet1 or Tet2 into the cytoplasm of zygotes resulted in more than 90% of newborn mice carrying mutations in both the genes as a result of imperfect repair by NHEJ. Furthermore, this coinjection of sgRNAs targeting Tet1 and Tet2 produced litters with up to 80% of animals showing biallelic mutations in both the genes, indicating the potential to rapidly generate double knockout animals in order to study gene interactions or to eliminate redundancy between closely related genes. Alternatively, coinjection of Cas9 nickase, which only cuts one strand of the DNA, with sgRNA pairs targeting the same gene can be used to reduce the potential for off-target cutting [18]. Impressively, the entire process, from sgRNA design to mouse production, can be performed within 1 month [14]. In contrast, generating double knockout animals using traditional gene targeting would require several rounds of breeding to achieve homozygosity for both genes. Additionally, unlike traditional gene targeting, this approach does not require experience with ES cell culture, and can be performed with microinjection equipment found in most research institutions. Some groups have developed zygote electroporation protocols to increase the throughput of gene editing by eliminating the slow step of microinjection [19,20]. Others have further accelerated the CRISPR/Cas GEMM strategy by eliminating the need for sgRNA cloning, demonstrating a method to produce sgRNAs directly from synthesized oligos [21].

While NHEJ-mediated editing is an effective strategy for single and multiplexed gene disruption, it has limitations. The random nature of the NHEJ repair mechanism makes it difficult to precisely model specific point mutations that may be associated with a disease. Mutant mice generated by NHEJ-based gene disruption can carry different insertions/deletions (indels) in the two alleles, and these mutations can be different for each mouse in the litter. This can potentially lead to inconsistent phenotypes between different founder mice and upon breeding. Additionally, as the mutations introduced by NHEJ are constitutive and ubiquitous, the approach cannot be used to achieve homozygous disruption of genes that are essential for embryonic development or adult viability. Genome editing via HDR from an added template mitigates these problems to some extent by enabling the insertion of defined point mutations or knock-in alleles as discussed above.

Although targeting by HDR is generally less efficient than NHEJ repair, Wang et al. [11] produced correctly targeted embryos by coinjection of a short single-stranded DNA template (ssDNA) together with the sgRNA and Cas9 mRNA into one-cell zygotes. Further optimization has established basic parameters for in vivo HDR: The donor template should be designed to span the Cas9 target site and PAM with ∼ 60 bp homology arms for small 1–2 nucleotide modifications, and should itself lack a full target sequence and PAM to prevent cleavage by the Cas9–sgRNA. For larger inserts, a circular double-stranded plasmid template with longer (1–3 kb) homology arms should be used instead [22]. The efficiency of in vivo HDR tends to decrease with the size of the modification: targeted insertion of point mutations can be achieved with 50–80% efficiency, while the efficiency of inserting small tags (e.g., V5) and larger inserts such as loxP cassettes declines to 30–50% and 10–20%, respectively [14]. Generating conditional alleles requires the simultaneous insertion of two loxP sites into the same allele, flanking the region to be excised, thereby further reducing the total efficiency. To address this limitation, several groups are developing strategies to increase the efficiency of HDR relative to NHEJ by inhibiting components of the NHEJ pathway such as Scr7, which inhibits DNA ligase IV [23–25].

The high efficiency of NHEJ creates an additional complication: a gene correctly targeted by HDR may be mutated by NHEJ on the other allele [11]. This limits the types of mutations that can be introduced for essential genes, and necessitates careful characterization of founder mice to limit variability upon breeding. Somatic mosaicism in founders is an additional source of potential variability [22]. An analysis by Yen et al. [26] detected > 2 alleles (indicating mosaicism) in up to 80% of founder mice that were generated by targeting the Tyrosinase gene. This mosaicism can be caused by editing after DNA replication of the region, such that different alleles are segregated among daughter cells. Delivery of Cas9 as a protein may reduce this issue by limiting the time window for gene editing [27,28]. Despite these caveats, CRISPR-based HDR in zygotes is a powerful approach to rapidly generate new conditional and reporter alleles without the need for ES cell manipulation. Importantly, it enables researchers to create these alleles on a wide variety of genetic backgrounds. This includes ones already carrying additional functional alleles such as Cre, as well as those that do not readily produce robust ES cells for traditional targeting, thereby eliminating multiple rounds of backcrossing to the desired genetic background.

A number of groups have already reported the use of CRISPR-based NHEJ and HDR in zygotes to create several disease models. For example, Li et al. [13] inserted mutations in the Fah gene into immunodeficient NRG mice, which have limited ES cell options for traditional targeting. Others created a panel of immunodeficient mice by disrupting up to five genes simultaneously [29]. CRISPR/Cas injection into zygotes has also been used to functionally test defined human point mutations thought to cause diseases such as lymphopenia, Leber congenital amaurosis, and infertility [30–32]. While mice are perhaps the most popular organism used to model human disease, CRISPR/Cas editing has been successful in a wide variety of other animals, including rats, pigs, and even nonhuman primates [33–35]. This opens the door to modeling diseases that have until now not been sufficiently well recapitulated in mouse models.

Somatic editing by CRISPR/Cas9

Several groups have developed specific delivery methods for Cas9 and sgRNAs to target both directly to the organ of interest in vivo. In case of the adult murine liver, naked DNA plasmids encoding Cas9 and sgRNAs can be easily delivered into parenchymal liver cells by hydrodynamic tail vein injection [36]. Using this delivery method, it was recently demonstrated that indel mutations of well-known tumor suppressor genes, such as Pten or p53, can lead to liver cancer formation similarly as observed by conditional Cre/loxP-based deletion [35]. Direct in vivo transfection is a unique capability of liver cells, thus most other studies rely on viral in vivo delivery. Here in particular, lentiviral constructs are used due to their broad tropism, their ability to infect postmitotic cells, and the fact that large genetic cargo can be delivered within a single construct. However, other studies also constructed adeno-associated (AAV)-based vector systems containing Cas9 and sgRNAs, which are more limited in cargo size. In an attempt to model nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC), Jacks and colleagues prepared a single lentivirus encoding Cas9, sgRNA, as well as Cre-recombinase and delivered this construct via intratra-cheal injection into cancer predisposed LSL-KrasG12D; p53fl/fl animals [37]. Using sgRNAs targeting established tumor suppressor genes (e.g., Pten, APC, or Nkx2.1), they observed specific indel mutations in respective target genes accompanied by accelerated tumorigenesis, demonstrating the versatility of CRISPR/Cas9 to model multistep lung cancer progression. In contrast, Zhang and coworkers applied CRISPR/Cas9 technology to disrupt genes in murine brains by AAV vectors [38]. Because AAV vectors are limited in cargo size, they designed a two-vector approach, where one AAV vector carried Cas9 and a second vector carried the sgRNA. Stereotactical injection of these AAV constructs was sufficient to disrupt up to three genes simultaneously in murine brains.

As mentioned above, the large size of Cas9 (4.1 kb) is a clear limiting factor for vector design and transduction efficiency of certain viral vectors. At 3.2 kb, the slightly smaller Cas9 ortholog characterized from Staphylococcus aureus can be packaged into AAV vectors for in vivo delivery, but still places constraints on additional cargo that can be inserted [39]. Thus, several laboratories generated mouse lines expressing Cas9 either constitutively or in a conditional manner using lox-stop-lox (LSL) strategies or doxycycline-inducible promoters driving Cas9 expression [40–42]. Importantly, no overt toxicities were observed, suggesting Cas9 expression in these lines is well tolerated. The obvious advantage of using such transgenic animals is that somatic genome engineering can now be achieved by efficient sgRNA delivery. This strategy is very versatile because different delivery methods such as lentiviruses, adenoviruses, or nanoparticles can be applied to disrupt gene expression in virtually every murine tissue in order to study different diseases in vivo [42]. Thus, Cas9-expressing mice provide a powerful tool that will enable rapid and simple discovery of gene function in a wide range of biological processes.

Although most in vivo studies have focused on generating indel mutations of individual genes to achieve loss-of-function alleles, some groups have been using CRISPR/Cas9 for HDR to generate or correct specific genetic mutations in vivo. The first report that HDR can be achieved in somatic cells in vivo comes from studies of mice harboring a mutation in the FAH gene, a model for hereditary tyrosinemia [43]. This mutation causes skipping of exon 8 during splicing and formation of truncated, unstable FAH protein, and FAH deficiency causes accumulation of toxic metabolites, such as fumarylacetoacetate, in hepatocytes, resulting in severe liver damage. Hydrodynamic delivery of a CRISPR/Cas9 construct contemporaneously with a repair oligonucleotide led to correction of this mutation accompanied by improved survival. However, the FAH model underlies a very strong selection pressure for FAH-positive cells and thus it is unlikely that such a dramatic phenotype can be observed after HDR in other scenarios. In lungs of Cas9 mice, for example, KrasG12D mutations, generated by adenoviral infection of an sgRNA together with repair template, were only observed in 0.1% at whole lobe level and only marginal enrichment of these cells was observed over time although this particular mutation should provide a selective advantage [42]. Similarly, again modeling in the liver, Jacks and colleagues observed 0.1% HDR efficiency utilizing hydro-dynamic delivery to generate targeted mutations of beta-catenin [35]. It therefore seems that NHEJ is preferred over HDR after CRISPR/Cas9-mediated double-strand brake induction and strategies that bias repair toward HDR could provide a great benefit for generating somatic mutations in vivo.

Ex vivo editing

An alternative strategy to model mutations in a tissue of interest is the ex vivo editing of isolated stem, progenitor, or tumor cells, followed by their transplantation into immunocompromised or syngeneic recipients (Fig. 1). Such ‘mosaic’ approaches are well suited to study gene function in the hematopoietic compartment, as it is possible to readily isolate hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, transduce genetic elements in vitro, and use these to reconstitute the immune system of irradiated recipient mice. Indeed, previous work has established the power of such approaches using short hairpin RNA (shRNA) vectors to suppress gene function by RNA interference (RNAi) [44,45]. Many of the same tools used to probe gene function using RNAi can be readily adapted to CRISPR/Cas9 systems, and studies suggest that gene targeting in the hematopoietic system using these tools can mimic loss-of-function phenotypes produced by gene deletion [46]. As previously shown for RNAi technology [47,48], CRISPR/Cas9 can be utilized for systematic unbiased screens to identify genes that play an important role in a variety of biological processes. That these screening approaches are feasible in vivo was recently demonstrated by Chen and colleagues, which performed a genome-wide screen for tumor growth and metastasis in nude mice [49]. Although this screen was informative, it only revealed genes that are already implicated in tumorigenesis and give a strong selection advantage (e.g., Pten, NF2) presumably due to the library size. Therefore, it seems that genome-wide pooled screens are too complex and smaller, and focused libraries will be better suited for in vivo screening applications. In addition to coding regions, CRISPR/Cas9 screens will allow to more systematically survey noncoding elements as recently reported [50].

Several studies indicate that CRISPR technology can be used to rapidly identify and characterize tumor suppressor gene function in vivo. In one example, Chen et al. showed that Mll3 disruption in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells cooperated with p53 and NF1 knockdown to accelerate the development of acute myeloid leukemia. Interestingly, despite the propensity of CRISPR/Cas9 to target both alleles, the leukemia triggered by Mll3-sgRNAs invariably retained one wild-type Mll3 allele [51]. This observation strongly suggests that MLL3 is an obligate haploinsufficient tumor suppressor, that is, loss of one Mll3 allele is sufficient to drive tumorigenesis. As with RNAi, viral CRISPR vectors can be modified to carry multiple sgRNAs and fluorescent reporter genes, to allow for multiplexed gene targeting and assessment of cooperation between genetic events. This is particularly useful for cancer modeling, as most tumors harbor multiple cooperating mutations. Illustrating the power of this approach, Ebert and colleagues used a small pool of lentiviral Cas9 and sgRNA vectors to mutate combinations of epigenetic regulators in mouse hematopoietic stem cells ex vivo [52]. The authors were able to track the edited cells in vivo, and were able to identify combinations of mutations that led to clonal expansion and cooperated in transformation to acute leukemia. This study also demonstrates the feasibility of pooled in vivo screening with CRISPR/Cas.

Although the hematopoietic system is most amenable to ex vivo editing, improvements in cell isolation and primary cell culture techniques are expanding the list of tissues that can be targeted in this way. For example, electroporation of CRISPR/Cas9 nickase has been used to disrupt the Rosa26 locus and the meiosis gene Stra8 in mouse spermatogonial stem cells [53]. Inserting a GFP reporter and puromycin resistance cassette allowed for selection of clones targeted by HDR and tracking of the cells upon transplantation, and transplanted Stra8-mutant clones recapitulated the impaired spermatogenesis phenotype of Stra8—/— mice. 2D and 3D culture conditions have been developed that allow for the growth and manipulation of wild-type or genetically altered cells from many tissues, including mammary gland, intestine, liver, and skin [54–57]. These and other tissues have been successfully probed for gene function by viral transduction and RNAi, and will likely be suitable for CRISPR-based interrogation. As is the case for ES cells, lines amenable to expansion from single cell clones will benefit from the ability to select specific mutations for transplantation. Indeed, CRISPR/Cas has been used to introduce mutations into normal human intestinal organoids using both NHEJ and HDR, in order to induce tumorigenesis or repair a mutated CFTR allele [58,59].

Chromosomal rearrangements and segmental deletions

The CRISPR/Cas9 system simply generates DNA double-strand breaks and can therefore lead to larger deletions, inversions, and translocations if two sgRNAs targeting two distal genomic sites are provided. Modeling these events in vivo can be important to understand underlying biology, as these structural genomic aberrations are often associated with disease. The feasibility of generating deletions, inversions, and duplications in six different noncoding genomic loci spanning 1.1 kb to 1.5 Mb was recently demonstrated using murine ES cells [60]. These ES cells were aggregated to generate chimeric mice and phenotypically, a 350 kb deletion at the murine Laf4 locus corresponding to deletions found in human patients recapitulated Nievergelt syndrome, a human bone deformation syndrome. The same group applied this approach further to model structural variants in the WNT6/IHH/EPHA4/PAX3 locus [61]. Beyond ES cells, it is also possible to use CRISPR methods to produce structural arrangements somatically. For example, viral delivery of two sgRNAs and Cas9 into murine lungs can result in an inversion and generation of an oncogenic Eml4-Alk fusion protein [62,63], which is frequently found in human patients, accompanied by lung tumor formation. That delivery of two distant sgRNAs can lead to genomic rearrangements is in fact sometimes an undesired off-target effect. Investigators using a multiplexed sgRNA approach to discover new tumor suppressor genes in liver cancer recently published this experience [64]. They delivered 18 sgRNAs simultaneously by hydrodynamic transfection into livers of cancer-prone mice. Aside from enrichment of individual sgRNAs, they could observe in several instances chromosomal deletions spanning several kilobases up to 62 Mb, and the chromosomal breakpoints corresponded to sgRNAs targeting individual genes. Thus although not intended, these results show that large segmental chromosomal alterations, which are frequently observed in human cancer, can be achieved in vivo using CRISPR/Cas9. However, the frequency of these events seems to be low and therefore efficient screening or positive selection methods are needed to enrich for the desired segmental alterations.

Gene repression and activation

Two distinct mutations can render Cas9 to an enzymatically ‘dead’ mutant protein (dCas9) [65]. Although unable to cleave DNA, dCas9 still retains the ability to bind to DNA guided by an sgRNA. Several research groups harnessed this ability and generated different dCas9 fusion proteins in order to direct proteins of interest to genomic regions. Particularly, interesting tools for interrogating gene expression are fusion proteins with transcriptional repression or activation domains. In contrast to genetic mutations that alter the target locus, these tools alter the expression of the endogenous gene and are in principle reversible. dCas9 fusions with KRAB-domains are broadly used for gene repression (CRISPRi) due to the potent recruitment of transcriptional repressors by KRAB-domains [66,67], whereas in order to achieve robust gene activation, several different approaches using dCas9 fused to transactivation domains (CRISPRa) have been pursued [66,68,69]. Previous studies have established the utility of inducible shRNA technology to study the temporal requirements for gene function and different stages of development and disease [70]. It seems likely that CRISPRi and CRISPRa will complement the shRNA approach, expanding the potential for studying gene function in vivo. While CRISPRi and shRNA tools have mainly redundant capabilities, CRISPRa brings capabilities that are unique in comparison with the traditional approach, cDNA overexpression. For example, CRISPRa allows control of an endogenous locus, and has advantage over conditional transgenes in that even large genes, which cannot readily be expressed by vector constructs, can be modulated. Therefore, the ability to activate endogenous genes by CRISPR/Cas might be a promising future application to study gene function and biology in vivo.

Conclusions

As is the case with most of the disruptive technologies that have impacted science and everyday living in the 20th and 21st centuries, the arrival of CRISPR on the scene was largely unanticipated. Yet, coupled with man's propensity to easily manipulate differentiated and precursor cells, and to sequence large swaths of RNA/DNA with high fidelity, we now have an unprecedented opportunity to create powerful genetic models in animal systems toward the better understanding of human disease. Even at this early stage, CRISPR-enabled genetic research has strengthened our grasp of the molecular underpinnings of several disease states. With further application by investigators, and refinement of the central tool set, one may easily envision a landscape where CRISPR-enabled GEMMS become the staple, default means of creating more informative man-made models systems to mimic natural biology, or even extending those results to directly impact the human condition via therapeutic intervention.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH P01-CA013106 Grant and the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748. Geulah Livshits was supported by NIH F32 grant 1F32CA177072-01. Scott W. Lowe has the Geoffrey Beene Chair for Cancer Biology and is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator.

Abbreviations

- Cas

CRISPR-associated protein

- CRISPR

clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

- GEMM

genetically engineered mouse model

- HDR

homology-directed repair

- NHEJ

nonhomologous end joining

- RNAi

RNA interference

- sgRNA

single guide RNA

References

- 1.Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright AV, Nuñez JK, Doudna JA. Biology and applications of CRISPR systems: harnessing nature's toolbox for genome engineering. Cell. 2016;164:29–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Church GM. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wijshake T, Baker DJ, van de Sluis B. Endonucleases: new tools to edit the mouse genome. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:1942–1950. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frese KK, Tuveson DA. Maximizing mouse cancer models. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:645–658. doi: 10.1038/nrc2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dow LE, Lowe SW. Life in the fast lane: mammalian disease models in the genomics era. Cell. 2012;148:1099–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas KR, Capecchi MR. Site-directed mutagenesis by gene targeting in mouse embryo-derived stem cells. Cell. 1987;51:503–512. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90646-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gu H, Marth JD, Orban PC, Mossmann H, Rajewsky K. Deletion of a DNA polymerase beta gene segment in T cells using cell type-specific gene targeting. Science. 1994;265:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.8016642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Utomo AR, Nikitin AY, Lee WH. Temporal, spatial, and cell type-specific control of Cre-mediated DNA recombination in transgenic mice. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:1091–1096. doi: 10.1038/15073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H, Yang H, Shivalila CS, Dawlaty MM, Cheng AW, Zhang F, Jaenisch R. One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell. 2013;153:910–918. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canver MC, Smith EC, Sher F, Pinello L, Sanjana NE, Shalem O, Chen DD, Schupp PG, Vinjamur DS, Garcia SP, et al. BCL11A enhancer dissection by Cas9-mediated in situ saturating mutagenesis. Nature. 2015;527:192–197. doi: 10.1038/nature15521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li F, Cowley DO, Banner D, Holle E, Zhang L, Su L. Efficient genetic manipulation of the NOD-Rag1-/-IL2RgammaC-null mouse by combining in vitro fertilization and CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5290. doi: 10.1038/srep05290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang H, Wang H, Jaenisch R. Generating genetically modified mice using CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Nat Protoc. 2014;9:1956–1968. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flemr M, Bühler M. Single-step generation of conditional knockout mouse embryonic stem cells. Cell Rep. 2015;12:709–716. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dow LE, Fisher J, O'Rourke KP, Muley A, Kastenhuber ER, Livshits G, Tschaharganeh DF, Socci ND, Lowe SW. Inducible in vivo genome editing with CRISPR-Cas9. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:390–394. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cui X, Ji D, Fisher DA, Wu Y, Briner DM, Weinstein EJ. Targeted integration in rat and mouse embryos with zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:64–67. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ran FA, Hsu PD, Lin CY, Gootenberg JS, Konermann S, Trevino AE, Scott DA, Inoue A, Matoba S, Zhang Y, et al. Double nicking by RNA-guided CRISPR Cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity. Cell. 2013;154:1380–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashimoto M, Takemoto T. Electroporation enables the efficient mRNA delivery into the mouse zygotes and facilitates CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11315. doi: 10.1038/srep11315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaneko T, Mashimo T. Simple genome editing of rodent intact embryos by electroporation. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aida T, Chiyo K, Usami T, Ishikubo H, Imahashi R, Wada Y, Tanaka KF, Sakuma T, Yamamoto T, Tanaka K. Cloning-free CRISPR/Cas system facilitates functional cassette knock-in in mice. Genome Biol. 2015;16:87. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0653-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang H, Wang H, Shivalila CS, Cheng AW, Shi L, Jaenisch R. One-step generation of mice carrying reporter and conditional alleles by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell. 2013;154:1370–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maruyama T, Dougan SK, Truttmann MC, Bilate AM, Ingram JR, Ploegh HL. Increasing the efficiency of precise genome editing with CRISPR-Cas9 by inhibition of nonhomologous end joining. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:538–542. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chu VT, Weber T, Wefers B, Wurst W, Sander S, Rajewsky K, Kühn R. Increasing the efficiency of homology-directed repair for CRISPR-Cas9-induced precise gene editing in mammalian cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:543–548. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu C, Liu Y, Ma T, Liu K, Xu S, Zhang Y, Liu H, La Russa M, Xie M, Ding S, et al. Small molecules enhance CRISPR genome editing in pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yen ST, Zhang M, Deng JM, Usman SJ, Smith CN, Parker-Thornburg J, Swinton PG, Martin JF, Behringer RR. Somatic mosaicism and allele complexity induced by CRISPR/Cas9 RNA injections in mouse zygotes. Dev Biol. 2014;393:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu J, Gaj T, Yang Y, Wang N, Shui S, Kim S, Kanchiswamy CN, Kim JS, Barbas CF. Efficient delivery of nuclease proteins for genome editing in human stem cells and primary cells. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:1842–1859. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh P, Schimenti JC, Bolcun-Filas E. A mouse geneticist's practical guide to CRISPR applications. Genetics. 2015;199:1–15. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.169771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou J, Shen B, Zhang W, Wang J, Yang J, Chen L, Zhang N, Zhu K, Xu J, Hu B, et al. One-step generation of different immunodeficient mice with multiple gene modifications by CRISPR/Cas9 mediated genome engineering. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;46:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siggs OM, Popkin DL, Krebs P, Li X, Tang M, Zhan X, Zeng M, Lin P, Xia Y, Oldstone MBA, et al. Mutation of the ER retention receptor KDELR1 leads to cell-intrinsic lymphopenia and a failure to control chronic viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E5706–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515619112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhong H, Chen Y, Li Y, Chen R, Mardon G. CRISPR-engineered mosaicism rapidly reveals that loss of Kcnj13 function in mice mimics human disease phenotypes. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8366. doi: 10.1038/srep08366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh P, Schimenti JC. The genetics of human infertility by functional interrogation of SNPs in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:10431–10436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1506974112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li W, Teng F, Li T, Zhou Q. Simultaneous generation and germline transmission of multiple gene mutations in rat using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:684–686. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Y, Du Y, Shen B, Zhou X, Li J, Liu Y, Wang J, Zhou J, Hu B, Kang N, et al. Efficient generation of gene-modified pigs via injection of zygote with Cas9/sgRNA. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8256. doi: 10.1038/srep08256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niu Y, Shen B, Cui Y, Chen Y, Wang J, Wang L, Kang Y, Zhao X, Si W, Li W, et al. Generation of gene-modified cynomolgus monkey via Cas9/RNA-mediated gene targeting in one-cell embryos. Cell. 2014;156:836–843. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bell JB, Podetz-Pedersen KM, Aronovich EL, Belur LR, McIvor RS, Hackett PB. Preferential delivery of the sleeping beauty transposon system to livers of mice by hydrodynamic injection. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:3153–3165. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sánchez-Rivera FJ, Papagiannakopoulos T, Romero R, Tammela T, Bauer MR, Bhutkar A, Joshi NS, Subbaraj L, Bronson RT, Xue W, et al. Rapid modelling of cooperating genetic events in cancer through somatic genome editing. Nature. 2014;516:428–431. doi: 10.1038/nature13906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swiech L, Heidenreich M, Banerjee A, Habib N, Li Y, Trombetta J, Sur M, Zhang F. In vivo interrogation of gene function in the mammalian brain using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:102–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ran FA, Cong L, Yan WX, Scott DA, Gootenberg JS, Kriz AJ, Zetsche B, Shalem O, Wu X, Makarova KS, et al. In vivo genome editing using Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Nature. 2015;520:186–191. doi: 10.1038/nature14299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carroll KJ, Makarewich CA, McAnally J, Anderson DM, Zentilin L, Liu N, Giacca M, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. A mouse model for adult cardiac-specific gene deletion with CRISPR/Cas9. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:338–343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523918113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chiou SH, Winters IP, Wang J, Naranjo S, Dudgeon C, Tamburini FB, Brady JJ, Yang D, Grüner BM, Chuang CH, et al. Pancreatic cancer modeling using retrograde viral vector delivery and in vivo CRISPR/Cas9-mediated somatic genome editing. Genes Dev. 2015;29:1576–1585. doi: 10.1101/gad.264861.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Platt RJ, Chen S, Zhou Y, Yim MJ, Swiech L, Kempton HR, Dahlman JE, Parnas O, Eisenhaure TM, Jovanovic M, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 knockin mice for genome editing and cancer modeling. Cell. 2014;159:440–455. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yin H, Xue W, Chen S, Bogorad RL, Benedetti E, Grompe M, Koteliansky V, Sharp PA, Jacks T, Anderson DG. Genome editing with Cas9 in adult mice corrects a disease mutation and phenotype. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:551–553. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hemann MT, Fridman JS, Zilfou JT, Hernando E, Paddison PJ, Cordon-Cardo C, Hannon GJ, Lowe SW. An epi-allelic series of p53 hypomorphs created by stable RNAi produces distinct tumor phenotypes in vivo. Nat Genet. 2003;33:396–400. doi: 10.1038/ng1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zuber J, Rappaport AR, Luo W, Wang E, Chen C, Vaseva AV, Shi J, Weissmueller S, Fellmann C, Fellman C, et al. An integrated approach to dissecting oncogene addiction implicates a Myb-coordinated self-renewal program as essential for leukemia maintenance. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1628–1640. doi: 10.1101/gad.17269211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malina A, Mills JR, Cencic R, Yan Y, Fraser J, Schippers LM, Paquet M, Dostie J, Pelletier J. Repurposing CRISPR/Cas9 for in situ functional assays. Genes Dev. 2013;27:2602–2614. doi: 10.1101/gad.227132.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zender L, Xue W, Zuber J, Semighini CP, Krasnitz A, Ma B, Zender P, Kubicka S, Luk JM, Schirmacher P, et al. An oncogenomics-based in vivo RNAi screen identifies tumor suppressors in liver cancer. Cell. 2008;135:852–864. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bric A, Miething C, Bialucha CU, Scuoppo C, Zender L, Krasnitz A, Xuan Z, Zuber J, Wigler M, Hicks J, et al. Functional identification of tumor-suppressor genes through an in vivo RNA interference screen in a mouse lymphoma model. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen S, Sanjana NE, Zheng K, Shalem O, Lee K, Shi X, Scott DA, Song J, Pan JQ, Weissleder R, et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screen in a mouse model of tumor growth and metastasis. Cell. 2015;160:1246–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Korkmaz G, Lopes R, Ugalde AP, Nevedomskaya E, Han R, Myacheva K, Zwart W, Elkon R, Agami R. Functional genetic screens for enhancer elements in the human genome using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:192–198. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen C, Liu Y, Rappaport AR, Kitzing T, Schultz N, Zhao Z, Shroff AS, Dickins RA, Vakoc CR, Bradner JE, et al. MLL3 is a haploinsufficient 7q tumor suppressor in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:652–665. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heckl D, Kowalczyk MS, Yudovich D, Belizaire R, Puram RV, McConkey ME, Thielke A, Aster JC, Regev A, Ebert BL. Generation of mouse models of myeloid malignancy with combinatorial genetic lesions using CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:941–946. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sato T, Sakuma T, Yokonishi T, Katagiri K, Kamimura S, Ogonuki N, Ogura A, Yamamoto T, Ogawa T. Genome editing in mouse spermatogonial stem cell lines using TALEN and double-nicking CRISPR/Cas9. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;5:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Welm BE, Dijkgraaf GJP, Bledau AS, Welm AL, Werb Z. Lentiviral transduction of mammary stem cells for analysis of gene function during development and cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:90–102. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koo BK, Stange DE, Sato T, Karthaus W, Farin HF, Huch M, van Es JH, Clevers H. Controlled gene expression in primary Lgr5 organoid cultures. Nat Meth. 2012;9:81–83. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nowak JA, Fuchs E. Isolation and culture of epithelial stem cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;482:215–232. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-060-7_14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huch M, Dorrell C, Boj SF, van Es JH, Li VSW, van de Wetering M, Sato T, Hamer K, Sasaki N, Finegold MJ, et al. In vitro expansion of single Lgr5+ liver stem cells induced by Wnt-driven regeneration. Nature. 2013;494:247–250. doi: 10.1038/nature11826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schwank G, Koo BK, Sasselli V, Dekkers JF, Heo I, Demircan T, Sasaki N, Boymans S, Cuppen E, van der Ent CK, et al. Functional repair of CFTR by CRISPR/Cas9 in intestinal stem cell organoids of cystic fibrosis patients. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:653–658. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Drost J, van Jaarsveld RH, Ponsioen B, Zimberlin C, van Boxtel R, Buijs A, Sachs N, Overmeer RM, Offerhaus GJ, Begthel H, et al. Sequential cancer mutations in cultured human intestinal stem cells. Nature. 2015;521:43–47. doi: 10.1038/nature14415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kraft K, Geuer S, Will AJ, Chan WL, Paliou C, Borschiwer M, Harabula I, Wittler L, Franke M, Ibrahim DM, et al. Deletions, inversions, duplications: engineering of structural variants using CRISPR/Cas in mice. Cell Rep. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lupiáñez DG, Kraft K, Heinrich V, Krawitz P, Brancati F, Klopocki E, Horn D, Kayserili H, Opitz JM, Laxova R, et al. Disruptions of topological chromatin domains cause pathogenic rewiring of gene-enhancer interactions. Cell. 2015;161:1012–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blasco RB, Karaca E, Ambrogio C, Cheong TC, Karayol E, Minero VG, Voena C, Chiarle R. Simple and rapid in vivo generation of chromosomal rearrangements using CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Cell Rep. 2014;9:1219–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maddalo D, Manchado E, Concepcion CP, Bonetti C, Vidigal JA, Han YC, Ogrodowski P, Crippa A, Rekhtman N, de Stanchina E, et al. In vivo engineering of oncogenic chromosomal rearrangements with the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Nature. 2014;516:423–427. doi: 10.1038/nature13902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weber J, Öllinger R, Friedrich M, Ehmer U, Barenboim M, Steiger K, Heid I, Mueller S, Maresch R, Engleitner T, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 somatic multiplex-mutagenesis for high-throughput functional cancer genomics in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:13982–13987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512392112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Qi LS, Larson MH, Gilbert LA, Doudna JA, Weissman JS, Arkin AP, Lim WA. Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-guided platform for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Cell. 2013;152:1173–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gilbert LA, Horlbeck MA, Adamson B, Villalta JE, Chen Y, Whitehead EH, Guimaraes C, Panning B, Ploegh HL, Bassik MC, et al. Genome-Scale CRISPR-mediated control of gene repression and activation. Cell. 2014;159:647–661. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gilbert LA, Larson MH, Morsut L, Liu Z, Brar GA, Torres SE, Stern-Ginossar N, Brandman O, Whitehead EH, Doudna JA, et al. CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell. 2013;154:442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chavez A, Scheiman J, Vora S, Pruitt BW, Tuttle M, PR Iyer E, Lin S, Kiani S, Guzman CD, Wiegand DJ, et al. Highly efficient Cas9-mediated transcriptional programming. Nat Methods. 2015;12:326–328. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Konermann S, Brigham MD, Trevino AE, Joung J, Abudayyeh OO, Barcena C, Hsu PD, Habib N, Gootenberg JS, Nishimasu H, et al. Genome-scale transcriptional activation by an engineered CRISPR-Cas9 complex. Nature. 2015;517:583–588. doi: 10.1038/nature14136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Premsrirut PK, Dow LE, Kim SY, Camiolo M, Malone CD, Miething C, Scuoppo C, Zuber J, Dickins RA, Kogan SC, et al. A rapid and scalable system for studying gene function in mice using conditional RNA interference. Cell. 2011;145:145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]