Abstract

Background

The incidence of outpatient visits for skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) has substantially increased over the last decade. The emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) has made the management of S. aureus SSTIs complex and challenging. The objective of this study was to identify risk factors contributing to treatment failures associated with community-associated S. aureus skin and soft tissue infections SSTIs.

Methods

This was a prospective, observational study among 14 primary care clinics within the South Texas Ambulatory Research Network. The primary outcome was treatment failure within 90 days of the initial visit. Univariate associations between the explanatory variables and treatment failure were examined. A generalized linear mixed-effect model was developed to identify independent risk factors associated with treatment failure.

Results

Overall, 21% (22/106) patients with S. aureus SSTIs experienced treatment failure. The occurrence of treatment failure was similar among patients with methicillin-resistant S. aureus and those with methicillin-susceptible S. aureus SSTIs (19 vs. 24%; p = 0.70). Independent predictors of treatment failure among cases with S. aureus SSTIs was a duration of infection of ≥7 days prior to initial visit [aOR, 6.02 (95% CI 1.74–19.61)] and a lesion diameter size ≥5 cm [5.25 (1.58–17.20)].

Conclusions

Predictors for treatment failure included a duration of infection for ≥7 days prior to the initial visit and a wound diameter of ≥5 cm. A heightened awareness of these risk factors could help direct targeted interventions in high-risk populations.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, Skin and soft tissue infections, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Epidemiology, Primary care

Background

The incidence of outpatient and emergency department visits for skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) has substantially increased with the emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) [1]. In the U.S., approximately 80–90% of SSTIs are due to S. aureus [2, 3]. Moreover, treatment failure is common after an initial S. aureus SSTI episode; recurrence rates have exceeded 50% in some populations [4]. Treatment failure may be multifactorial and can be associated with host factors, disease management, and pathogen features. Two studies set in urgent care and primary care clinics found 35% of patients with CA-MRSA SSTIs experienced treatment failure and 78% reported SSTI recurrence [5, 6]. SSTIs due to CA-MRSA have been implicated to have more serious outcomes compared to community-associated methicillin susceptible S. aureus (CA-MSSA) SSTIs; however, there are limited studies evaluating the differences in treatment outcomes in the primary care setting. Furthermore, while there has been a growing body supporting the assessment of early response in treatment failure among hospitalized patients with SSTIs, very little information is available for outpatients [7, 8]. Tools to better identify those who are at higher risk of experiencing treatment failure are needed to better inform treatment decisions in the outpatient setting.

We have recently described the prevalence, treatment characteristics, and costs associated with the management of CA-MRSA SSTIs in South Texas in the primary care setting [9, 10]. The primary objective of this study was to identify risk factors contributing to S. aureus SSTI treatment failures.

Methods

Study setting and population

We performed this investigation among a well-described cohort of patients with SSTIs in the primary care setting. Details of this cohort have been described previously [9–11]. Briefly, this study was conducted in collaboration with fourteen clinics within the South Texas Ambulatory Research Network (STARNet), a practice-based research network (PBRN) composed of 108 urban, suburban, and rural primary care clinics distributed throughout the South Texas region, from 2007 to 2014. Patients were eligible for study enrollment if they provided informed consent, were 18 years of age or older, and presented to one of the participating clinics with an SSTI. Healthcare providers collected a wound sample and patient information (e.g., demographics, infection characteristics, clinical information).

Study design

We conducted a prospective observational cohort study to determine predictors of treatment failure. Currently, there is no consensus definition of treatment failure. We have based our definition based on prior studies using a proxy of therapeutic endpoints for SSTIs in the outpatient setting [9–14]. Treatment failure was defined as any of the following events within 90 days of their initial visit: (1) need for a new course or change in antibiotic therapy for SSTI, (2) additional incision and drainage, (3) SSTI at a new site, (4) SSTI at the same site, (5) emergency department visit, or (6) hospital admission. First, we compared the rate of treatment failure for patients with MRSA infections to those with MSSA infections. Next, we identified independent risk factors associated with treatment failure by comparing key characteristics in those patients who did and did not experience treatment failure.

Microbiologic analyses

Samples were plated onto blood agar plates (TSA with 5% sheep blood; Fisher Scientific, Lenexa, KS) and incubated at 35–37 °C for 24 h, then sub-cultured to MRSA selective agar (MRSASelect chromogenic agar plates; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Latex agglutination tests (StaphAurex®; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lenexa, KS), and phenotypic screening tests (cefoxitin) were used for the identification and isolation of MRSA using Vitek 2 AST-GP75 cards (bioMerieux, Durham, NC). Antimicrobial minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were interpreted according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute document M100-S22 (2012). Multidrug resistance (MDR) was defined as resistant to >2 antimicrobial classes. For molecular analysis, multilocus sequence types (MLST) were assigned for 98 isolates using whole genome sequence data according to designated MLST (http://www.mlst.net) as described previously [11].

Data collection and variables

Clinical information included patient gender, race (Black, White, Other), ethnicity (Hispanic, Non-Hispanic), past medical history (e.g., diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, chronic non-infectious skin disorder, HIV/AIDS, cancer, actively receiving chemotherapy, immunosuppression), health care-related work history, skin infection history, height, infection characteristics (e.g., location, duration, size, deepest tunnel depth, erythema, smell, ulceration, drainage, abscess, satellites), incision and drainage procedures, and antibiotics prescribed. A BMI ≥30 kg/m2 was used to indicate obesity status. A 110 kg weight cutoff was used to indicate ‘high body weight’. This is consistent with previous literature associating high body weight with antimicrobial dosing outcomes [15–17]. In addition, this cut-off was internally derived using a Classification and Regression Tree (CART) analysis which found a significant node at 110 kg that partitioned the data associated with treatment failure.

Statistical analyses

First, a bivariable analysis was conducted comparing variables between the ‘treatment failure’ and ‘no treatment failure’ groups. The Breslow-Day test was used to identify possible effect modification; any p ≤ 0.05 was considered an effect modifier. A generalized linear mixed-effect model was developed to identify independent risk factors; clinic site was set as the random effect. Covariates included MRSA phenotype, largest diameter size of the wound ≥5 cm, and duration of skin infection prior to visit of ≥7 days. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. A p ≤ 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. SPSS 22.0® (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) was used for all statistical comparisons.

Results

Among cases with positive S. aureus SSTIs, 106 cases (61%) had 90-days follow-up information. Overall, 22 (21%) cases experienced treatment failure. Treatment failure occurred in 19% (13) of cases with initial MRSA SSTIs and 24% (9) with MSSA SSTIs (p = 0.70). In bivariable analysis, factors associated with treatment failure included Black race, weight ≥110 kg, MDR, duration of skin infection prior to visit ≥7 days, lesion diameter ≥5 cm, lesion size ≥25 cm2, and abscess formation (Table 1). Multivariable analysis showed no significant difference in the likelihood of treatment failure between MRSA and MSSA (aOR, 0.42 (0.12–1.42); p = 0.16). Independent predictors of treatment failure among cases with S. aureus SSTIs were duration of skin infection prior to visit ≥7 days [aOR, 6.02 (95% CI 1.74–19.61)], and a lesion diameter size ≥5 cm [aOR, 5.25 (95% CI 1.58–17.20)].

Table 1.

Risk factors associated with treatment failure among patients with community-associated S. aureus skin and soft tissue infections

| Characteristic | Overall, n = 106 | No failure, n = 84 | Treatment failure, n = 22 | OR (95% CI) | p | aOR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (±SD) | 41 (±14) | 40 (±13) | 45 (±13) | 0.15 | |||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 53 (50%) | 44 (52%) | 9 (41%) | 0.63 (0.24–1.63) | 0.34 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Black | 8 (8%) | 4 (5%) | 4 (18%) | 4.44 (1.02–19.47) | 0.03 | ||

| Hispanic | 78 (74%) | 64 (76%) | 14 (64%) | 0.547 (0.20–1.49) | 0.23 | ||

| Diabetes | 28 (26%) | 21 (25%) | 7 (32%) | 1.40 (0.50–3.89) | 0.52 | ||

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30)b | 50 (54%) | 38 (50%) | 12 (71%) | 2.40 (0.77–7.48) | 0.12 | ||

| Weight ≥110 kg | 19 (20%) | 12 (15%) | 7 (37%) | 3.21 (1.05–9.80) | 0.04 | ||

| Chronic non-infectious skin disorder | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | 1.00 | ||

| Immunosuppressed at time of visit | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 0 | 0.98 (0.94–1.01) | 1.00 | ||

| Provides healthcare to others | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | 1.00 | ||

| MRSA phenotype | 68 (65%) | 55 (66%) | 13 (59%) | 0.87 (0.49–1.56) | 0.65 | 0.42 (0.12–1.42) | 0.16 |

| MDR | 29 (27%) | 10 (12%) | 19 (86%) | 2.85 (1.07–7.62) | 0.03 | ||

| Prior SSTI | 35 (33%) | 27 (32%) | 8 (36%) | 1.21 (0.45–3.20) | 0.71 | ||

| Prior antibiotic history | 16 (15%) | 11 (13%) | 5 (23%) | 1.95 (0.60–6.36) | 0.32 | ||

| Duration of infection prior to visit ≥7 days | 48 (48%) | 32 (40%) | 16 (76%) | 4.80 (1.59–14.41) | <0.01 | 6.02 (1.74–20.87) | <0.01 |

| Severity | |||||||

| Largest diameter ≥5 cm | 49 (48%) | 34 (42%) | 15 (71%) | 3.53 (1.24–10.02) | 0.01 | 5.25 (1.58–17.42) | <0.01 |

| Lesion area ≥25 cm2 | 37 (35%) | 24 (29%) | 13 (59%) | 3.55 (1.34–9.39) | 0.01 | ||

| Infection characteristics | |||||||

| Erythema | 78 (74%) | 61 (74%) | 17 (77%) | 1.23 (0.40–3.72) | 0.72 | ||

| Drainage | 56 (53%) | 45 (54%) | 11 (50%) | 0.84 (0.33–2.16) | 0.72 | ||

| Ulceration | 30 (29%) | 22 (27%) | 8 (36%) | 1.58 (0.59–4.29) | 0.43 | ||

| Abscess | 76 (72%) | 56 (67%) | 20 (91%) | 4.82 (1.05–22.14) | 0.03 | ||

| Location | |||||||

| Lower extremity | 35 (33%) | 26 (31%) | 9 (41%) | 1.54 (0.59–4.06) | 0.38 | ||

| Head/neck/face | 11 (10%) | 10 (12%) | 1 (5%) | 0.35 (0.40–2.91) | 0.45* | ||

| Trunk | 24 (23%) | 17 (20%) | 7 (32%) | 1.84 (0.65–5.22) | 0.26* | ||

| Axilla | 13 (12%) | 11 (13%) | 2 (9%) | 0.66 (0.14–3.24) | 0.61* | ||

| Upper extremity | 6 (6%) | 5 (6%) | 1 (5%) | 0.75 (0.08–6.79) | 1.00* | ||

| Groin/buttock | 17 (16%) | 14 (17%) | 3 (14%) | 0.79 (0.21–3.03) | 1.00* | ||

| Treatment | |||||||

| I&D only | 4 (4%) | 3 (4%) | 1 (5%) | 1.01 (0.91–1.12) | 1.00 | ||

| I&D + antibiotics | 57 (59%) | 43 (51%) | 14 (64%) | 1.30 (0.68–2.51) | 0.41 | ||

| Antibiotics only | 32 (33%) | 27 (36%) | 5 (24%) | 0.84 (0.63–1.13) | 0.29 | ||

| Antibiotics | |||||||

| Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole | 81 (76%) | 65 (77%) | 16 (73%) | 0.78 (0.27–2.27) | 0.65 | ||

| Doxycycline | 12 (11%) | 9 (11%) | 3 (14%) | 1.32 (0.32–5.34) | 0.71 | ||

| Clindamycin | 7 (7%) | 5 (6%) | 2 (9%) | 1.58 (0.26–8.75) | 0.63 | ||

| Cephalexin | 9 (9%) | 7 (8%) | 2 (9%) | 1.10 (0.21–5.71) | 1.00 | ||

| Discordant therapy | 5 (5%) | 3 (4%) | 2 (11%) | 2.82 (0.44–18.24) | 0.26 | ||

Note there were no cases of patients with the peripheral vascular disease, human immunodeficiency virus, cancer, and receipt of chemotherapy

MRSA methicillin resistant S. aureus, MSSA methicillin susceptible S. aureus, SD standard deviation, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, aOR adjusted odds ratio, SSTI skin and soft tissue infection, BMI body mass index, I&D incision and drainage

* Fishers exact test was used

Infection location, specific treatment strategies, or prescribed antimicrobial agents were not significantly associated with treatment failure. The proportion of discordant antimicrobial agents prescribed was higher in the treatment failure group than in the no-failure group, but did not reach statistical significance (11 vs. 4%, p = 0.20) which may be an artifact of the small sample size. MRSA isolates had significantly lower susceptibility to ciprofloxacin (p < 0.01) and erythromycin (p < 0.01). Two isolates (1 MRSA and 1 MSSA) were D-test positive.

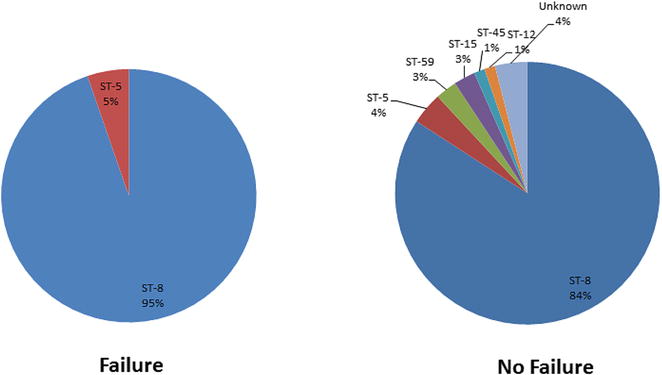

Molecular analysis (Fig. 1) was conducted on 98 isolates: 56% (65/116) of CA-MRSA and 43% (32/75) of CA-MSSA. All MRSA isolates and 68% of MSSA isolates were MLST strain type (ST) 8. Other MSSA strain types included: ST5, ST12, ST-15, ST-20, ST-45, and ST-59. Four isolates had undefined MLST designation. Furthermore, 95% of S. aureus SSTI treatment failures were ST-8 compared to 84% of cases with no treatment failure (p = 0.32).

Fig. 1.

Multilocus sequence typing of Staphylococcus aureus isolates associated with treatment failure or no treatment failure

Discussion

Over the past 10 years, ambulatory care visits for SSTIs have increased exponentially. The worldwide emergence of CA-MRSA strains has made the management of S. aureus SSTIs extremely complicated and challenging [2, 3]. A clinical approach to the management of S. aureus SSTIs is to identify risk factors to predict those who are more likely to experience treatment failure.

Although it has been postulated that CA-MRSA related SSTIs may be associated with worse outcomes, SSTIs caused by MRSA did not have worse outcomes than those caused by MSSA in the South Texas community. Miller et al. found similar 30-day response rates among patients with CA-MRSA and CA-MSSA infection (23 [33%] of 70 vs. 13 [28%] of 47 patients; p = 0.55). In addition, patients with CA-MSSA infections were more likely to be re-hospitalized and to subjectively believe that they had not been cured [18]. Moreover, a previous randomized clinical trial of children with suspected S. aureus SSTIs found that the incidence of recurrence did not differ between children with MRSA vs. MSSA baseline infections [14]. Our findings further support the notion that the methicillin resistance phenotype is not a reliable predictor for clinical outcomes of community associated S. aureus infections. Rather, community associated S. aureus should be considered a single entity when evaluating virulence risks.

Identifying predictors for clinical failure can help target more aggressive treatment, monitoring, and decolonization procedures. This study identified that duration of infection 7 days and longer prior to the initial visit was the strongest predictor of treatment failure. This may be related to the natural course of infection that patients were presenting at a time of maximum intensity of inflammation and infection. Moreover, it may be that longer duration of an active S. aureus infection without proper treatment may have increased the likelihood for household or fomite transmission, both which have been shown to be important factors for infection recurrence [19–21]. This finding is in contrast to a recent study that found longer duration of symptoms was among the factors related to early response (at day 3). However, the investigation evaluated antibiotic response at day 3 among hospitalized SSTI patients; therefore, may not necessarily be associated with long-term outcomes including post-treatment failure and recurrence that were evaluated in the current study [7]. Importantly, this finding further supports the proposition that time to effective treatment is essential in the management of SSTIs, and possibly, that patients presenting with longer duration (≥7 days) of infections may require more aggressive measures and/or follow-up monitoring.

In addition, a lesion diameter of greater than 5 cm was associated with treatment failure. Lesion size has been used as a proxy for severity in several syndromes of skin infections, including necrotizing fasciitis and surgical site infections [22]. The 5 cm threshold used in this study was based on data from an observational study, in which abscesses larger than 5 cm were associated with treatment failure [23]. This investigation found a significant predictor of hospitalization on the first follow-up was having an infected area >5 cm in diameter at the initial evaluation (33% of patients with diameter >5 cm were later hospitalized vs. none with diameter ≤5 cm; p = 0.004). Other studies have also identified lesion size as an important indicator for severity and suggest treatment stratification approaches [24–26]. In the most recent guidelines for acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection (ABSSSI) clinical trials, the FDA recommends an evaluation of lesion size as a more quantitative assessment of infection severity and the change in lesion size at 48 to 72 h as the new primary endpoint [27]. Our findings provide further support to assess initial lesion sizes to predict infection severity and treatment outcomes.

Specific treatment strategies or type of prescribed antimicrobial agents were not found to be independent factors associated with treatment failure. It should be noted that because of the limited sample size, this study was not designed to perform direct comparisons of treatment approaches and antibiotic therapies. Larger investigations are needed to compare the role of treatment strategies and antibiotic regimens.

In our molecular analyses, ST-8 was the predominant strain type and was more likely to be found in patients whose treatment failed. However, this 11% absolute difference did not reach statistical significance due to the size of our cohort. This might suggest that the pathogenicity of community associated S. aureus may be based on the genetic background or lineage rather than the methicillin susceptibility phenotype. A more thorough investigation on the genomic characteristics of these strains is currently underway.

There are limitations to this study. First, we did not account for social and behavioral risk factors that may be associated with S. aureus SSTIs and/or clinical outcomes. Second, we used laboratory diagnosis to identify S. aureus cases. Patients presenting with SSTIs with no culture or were culture-negative may have different characteristics. The small sample size limited the ability to identify risks associated with lower exposures. Compliance of antimicrobials prescribed was not assessed. Finally, there may be limited generalizability to other regions outside of South Texas. To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study evaluating the clinical and epidemiological factors of S. aureus SSTI treatment failure in the primary care setting, adding important findings to the sparse literature in this growing population.

Conclusions

The rates of treatment failure were similar among patients with CA-MRSA SSTIs to those with CA-MSSA SSTIs. Independent predictors for treatment failure included a duration of infection for greater than 7 days prior to the initial visit and a wound diameter of ≥5 cm. A heightened awareness of these risk factors could help direct clinical management and public health interventions in high-risk populations. Future large prospective investigations are required to validate these findings and to assess optimal treatment approaches.

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design of work: GCL and CRF; Data collection: GCL, SDD, LCD, LBT, SBT, CRF; Data analysis and interpretation: GCL, RGH, CRF; Drafting of manuscript: GCL; Critical revision of manuscript: RGH, NKB, KAL, JAW, RJO, YW, CRF. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank their South Texas Ambulatory Research Network (STARNet) and Area Health Education Center (AHEC) colleagues, including Paula Winkler, who assisted with the administrative aspects of the study. We also thank Khine Tun for editing and formatting the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Declaration

The University of Texas Health Science Center Institutional Review Board granted approval for this study.

Funding statement

This study was funded by an investigator-initiated research grant from Pfizer to Dr. Frei. Dr. Frei was also supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health in the form of a KL2 Career Development Award (NIH/NCRR 5KL2 RR025766, PI-Robert Clark).

Abbreviations

- SSTIs

skin and soft tissue infections

- CA-MRSA

community-associated methicillin resistant S. aureus

- CA-MSSA

community-associated methicillin susceptible S. aureus

- STARNet

South Texas Ambulatory Research Network

- PBRN

practice-based research network

- MICs

minimum inhibitory concentrations

- MDR

multidrug resistance

- MLST

multilocus sequence type

- CART

classification and regression tree

- ORs

odds ratios

- CIs

confidence intervals

- aOR

adjusted odd ratio

- SD

standard deviation

- BMI

body mass index

- I&D

incision and drainage

- ST

strain type

Contributor Information

Grace C. Lee, Phone: (210) 567-8371, Email: leeg3@uthscsa.edu

Ronald G. Hall, Email: Ronald.hall@ttuhsc.edu

Natalie K. Boyd, Email: nkboyd@uthscsa.edu

Steven D. Dallas, Email: DallasS@uthscsa.edu

Liem C. Du, Email: liem.du@uhs-sa.com

Lucina B. Treviño, Email: trevinofamilyclinic@yahoo.com

Sylvia B. Treviño, Email: trevinofamilyclinic@yahoo.com

Chad Retzloff, Email: Chad.retzloff@uhs-sa.com.

Kenneth A. Lawson, Email: ken.austin@austin.utexas.edu

James Wilson, Email: james.wilson@austin.utexas.edu.

Randall J. Olsen, Email: rjolsen@houstonmethodist.org

Yufeng Wang, Email: yufeng.wang@utsa.edu.

Christopher R. Frei, Email: freic@uthscsa.edu

References

- 1.Pallin DJ, Egan DJ, Pelletier AJ, Espinola JA, Hooper DC, Camargo CA., Jr Increased US emergency department visits for skin and soft tissue infections, and changes in antibiotic choices, during the emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ray GT, Suaya JA, Baxter R. Incidence, microbiology, and patient characteristics of skin and soft-tissue infections in a U.S. population: a retrospective population-based study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:252. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ray GT, Suaya JA, Baxter R. Microbiology of skin and soft tissue infections in the age of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;76:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Creech CB, Al-Zubeidi DN, Fritz SA. Prevention of recurrent Staphylococcal skin infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29:429–464. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frei CR, Miller ML, Lewis JS, 2nd, et al. Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole or clindamycin for community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) skin infections. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23:714–719. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2010.06.090270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parchman ML, Munoz A. Risk factors for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcal aureus skin and soft tissue infections presenting in primary care: a South Texas Ambulatory Research Network (STARNet) study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22:375–379. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.04.090003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruun T, Oppegaard O, Hufthammer KO, et al. Early response in cellulitis: a prospective study of dynamics and predictors. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;15:1034–1041. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amara S, Adamson RT, Lew I, et al. Clinical response at Day 3 of therapy and economic outcomes in hospitalized patients with acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection (ABSSSI) Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29:869–877. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2013.803056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forcade NA, Parchman ML, Jorgensen JH, et al. Prevalence, severity, and treatment of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) skin and soft tissue infections in ten medical clinics in Texas: a South Texas Ambulatory Research Network (STARNet) study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:543–550. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.05.110073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Labreche MJ, Lee GC, Attridge RT, et al. Treatment failure and costs in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) skin and soft tissue infections: a South Texas Ambulatory Research Network (STARNet) study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:508–517. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2013.05.120247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee GC, Long SW, Musser JM, et al. Comparative whole genome sequencing of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus sequence type 8 from primary care clinics in a Texas community. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35:220–228. doi: 10.1002/phar.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bocchini CE, Mason EO, Hulten KG, et al. Recurrent community-associated Staphylococcus aureus infections in children presenting to Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston Texas. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:1189–1193. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182a5c30d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fritz SA, Hogan PG, Hayek G, et al. Household versus individual approaches to eradication of community-associated Staphylococcus aureus in children: a randomized trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:743–751. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan SL, Forbes A, Hammerman WA, et al. Randomized trial of “bleach baths” plus routine hygienic measures vs. routine hygienic measures alone for prevention of recurrent infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:679–682. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubino CM, Van Wart SA, Bhavnani SM, Ambrose PG, McCollam JS, Forrest A. Oritavancin population pharmacokinetics in healthy subjects and patients with complicated skin and skin structure infections or bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4422–4428. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00231-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falagas ME, Karageorgopoulos DE. Adjustment of dosing of antimicrobial agents for bodyweight in adults. Lancet. 2010;375:248–251. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60743-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gillon JE, Cassat JE, Di Pentima MC. Validation of two vancomycin nomograms in patients 10 years of age and older. J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;54:35–38. doi: 10.1002/jcph.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller LG, Quan C, Shay A, et al. A prospective investigation of outcomes after hospital discharge for endemic, community-acquired methicillin-resistant and -susceptible Staphylococcus aureus skin infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:483–492. doi: 10.1086/511041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller LG, Diep BA. Clinical practice: colonization, fomites, and virulence: rethinking the pathogenesis of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:752–760. doi: 10.1086/526773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uhlemann AC, Dordel J, Knox JR, et al. Molecular tracing of the emergence, diversification, and transmission of S. aureus sequence type 8 in a New York community. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:6738–6743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401006111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uhlemann AC, Kennedy AD, Martens C, Porcella SF, Deleo FR, Lowy FD. Toward an understanding of the evolution of Staphylococcus aureus strain USA300 during colonization in community households. Genome Biol Evol. 2012;4:1275–1285. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evs094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:147–159. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee MC, Rios AM, Aten MF, Mejias A, Cavuoti D, McCracken GH, Jr, Hardy RD. Management and outcome of children with skin and soft tissue abscesses caused by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:123–127. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000109288.06912.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller LG, Daum RS, Chambers HF. Antibacterial treatment for uncomplicated skin infections. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2460. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1504843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller LG, Daum RS, Creech CB, et al. Clindamycin versus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for uncomplicated skin infections. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1093–1103. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eron LJ, Lipsky BA, Low DE, et al. Managing skin and soft tissue infections: expert panel recommendation. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52(Suppl 1):i3–i17. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Itani KM, Shorr AF. FDA guidance for ABSSSI trials: implications for conducting and interpreting clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(1):S4–S9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]