Abstract

We hypothesized that one mechanism underlying the association between obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and Alzheimer Disease is OSA leading to decreased slow wave activity, increased synaptic activity, decreased glymphatic clearance, and increased amyloid-β. Polysomnography and lumbar puncture were performed in OSA and control groups. Slow wave activity negatively correlated with cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-β-40 among controls and was decreased in the OSA group. Unexpectedly, amyloid-β-40 was decreased in the OSA group. Other neuronally-derived proteins, but not total protein, were also decreased in the OSA group, suggesting that OSA may affect the interaction between interstitial and cerebrospinal fluid.

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is characterized by upper airway collapse, leading to recurrent arousals and hypoxia. OSA increases risk of cognitive decline, particularly Alzheimer Disease (AD).1–2 The earliest known process in AD pathogenesis is the aggregation of soluble amyloid-β (Aβ) into insoluble amyloid plaques. Soluble Aβ in the interstitial fluid (ISF) decreases during sleep and increases during wakefulness.3–4 Slow wave activity (SWA) during sleep is the electroencephalographic (EEG) sign of cortical neurons pausing synaptic activity,5 which is theorized to underlie decreased cortical metabolic rates of ~40% during SWA compared to wakefulness in both humans6 and mice.7 Since synaptic activity results in release of Aβ from neurons,7 SWA should lead to decreased Aβ. Furthermore, the glymphatic system functions maximally during SWA to clear Aβ and other metabolites from the interstitial space.8 Mouse models of AD have demonstrated that sleep restriction increases soluble Aβ levels acutely and amyloid deposition chronically.4 In humans, sleep deprivation increases cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ.9 We therefore hypothesized that frequent arousals in OSA cause decreased SWA, leading to increased Aβ, and eventually to increased Aβ aggregation into amyloid, and increased AD risk. We tested this hypothesis by examining SWA and CSF Aβ in individuals with and without OSA.

Methods

Participants were recruited from Volunteer for Health, a community-based registry, and the Washington University Sleep Center. Inclusion criteria were age 45–65 years, body mass index 18–35 kg/m2, sleeping “about the same” or “slightly worse” in unfamiliar situations compared to at home, bedtime 8PM-midnight, and wake time 4AM-8AM. Exclusion criteria included other sleep disorders, prior OSA treatment, co-morbidities except hypertension, neuro-active medications, alcohol >14 drinks/week, and Mini-Mental Status Exam score <27. All participants provided informed, written consent. All procedures were approved by the Washington University Human Research Protection Office.

Sleep was monitored with actigraphy (Actiwatch2™, Philips-Respironics) for 5–14 days to confirm regular sleep patterns immediately prior to overnight polysomnography. Polysomnograms were scored by a registered polysomnographic technologist.10 The apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) determined whether a participant was in the OSA group (AHI >15) or Control group (AHI <5).

SWA was quantified from EEG during polysomnography by delta power, the spectral power in the delta (0.5–4 Hz) frequencies. EEG data were acquired at 200 Hz. A Matlab™ (Mathworks) script was written to extract EEG data from frontal electrodes, segment data into 10.24-second mini-epochs, and calculate delta power using the Signal Processing Toolbox bandpower function. Delta power was averaged for 3 overlapping mini-epochs for each 30-second sleep epoch, then averaged for all non-rapid eye movement sleep epochs.

Cerebrospinal fluid was obtained by lumbar puncture at 9:30–10AM following polysomnography. This time corresponds to the daily nadir of CSF Aβ.3 Participants fasted until after lumbar puncture. CSF was immediately placed on ice, aliquoted, and frozen at −80°C. Aβ40 was chosen as the primary measure of Aβ since it is the most abundant Aβ species and less subject to decreased levels caused by existing amyloid plaques.11 Aβ40, Aβ42, Tau, and phosphorylated-Tau-181 (pTau181) were assessed by immunoassay as described.11 Total protein was assessed by Bradford assay (Thermo Pierce). Visinin-like protein-1 (VILIP-1), a neuronal protein, and neurogranin and synaptosomal-associated protein 25kD (SNAP-25), synaptic proteins, were measured via an Erenna analyzer (Singulex) using reagents and protocols developed in JHL’s laboratory.11–12 All CSF measurements were performed in duplicate or triplicate with several internal control samples.

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 22 (IBM). Continuous variables were compared with Student’s T-tests, categorical variables were compared with Fisher’s exact tests, and correlations were assessed with Spearman’s correlation coefficient.

Results

Fifty-eight participants completed the study. Participants were excluded for AHI 5–15 (n=13) and inability to obtain CSF (n=1). We previously proposed a bi-directional feedback loop between AD pathology and sleep disturbance beginning in middle age.13–14 In order to assess the effect of OSA on CSF Aβ without the confound of AD pathology in which amyloid plaques act as a sink for soluble Aβ, we excluded participants with Aβ42 <500 pg/mL (n=3). The final groups were 31 Control and 10 OSA participants. The OSA group had higher mean body mass index, otherwise the groups were clinically similar. (Table 1) While the SaO2 nadir during polysomnography was significantly lower in the OSA group as expected, the time spent with clinically relevant hypoxia (% time with SaO2 <90%) was not different between groups, underscoring that AHI captures relative oxygen desaturations rather than hypoxia per se.

Table 1.

| Control (n=31) | OSA (n=10) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and clinical | |||

| Age years | 53.2 ±5.7 [45.8–65.7] | 56.4 ±4.0 [48–62] | 0.110 |

| Sex male (%) | 16 (52%) | 7 (70%) | 0.467 |

| Race Caucasian (%) | 18 (58%) | 5 (50%) | 0.724 |

| Body mass index | 26.6 ±3.9 [19.1–33.4] | 29.6 ±3.7 [22.6–35.0] | 0.038 |

| Education years | 15.1 ±2.5 [12–20] | 15.3 ±2.3 [12–18] | 0.849 |

| Hypertension (%) | 6 (19%) | 4 (40%) | 0.222 |

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale | 6.8 ±4.5 [0–18] | 9.2 ±5.0 [3–19] | 0.156 |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | 4.6 ±3.2 [1–13] | 4.9 ±2.4 [2–8] | 0.776 |

| Sleep | |||

| Total sleep time (minutes) | 391 ±44 [312–477] | 356 ±70 [219–456] | 0.065 |

| REM (minutes) | 80 ±23 [38–128] | 67 ±24 [28–100] | 0.120 |

| NREM (minutes) | 311 ±38 [240–390] | 289 ±54 [190–379] | 0.156 |

| Sleep latency (minutes) | 20 ±23 [0–89] | 21 ±27 [0–85] | 0.897 |

| REM latency (minutes) | 88 ±66 [6–375] | 106 ±81 [29–258] | 0.480 |

| Sleep efficiency (%) | 79 ±9 [52–91] | 75 ±11 [46–88] | 0.065 |

| Apnea-Hypopnea Index | 1.6 ±1.4 [0–4.9] | 28.6 ±12.5 [17–50] | <0.001 |

| SaO2 nadir (%) | 89 ±2.6 [84–94] | 80 ±11.1 [50–89] | 0.031 |

| Time below SaO2 90% (% of study) | 3.2 ±9.8 [0–51] | 4.0 ±4.2 [0.2–12.7] | 0.817 |

| Awakenings (number) | 9.6 ±5.0 [3–24] | 9.5 ±3.6 [5–15] | 0.933 |

| WASO (minutes) | 80 ±53 [14–238] | 111 ±38 [60–153] | 0.091 |

| PLMI | 11 ±21 [0–87] | 5 ±17 [0–53] | 0.464 |

| Arousal index | 13.0 ±8.3 [2.7–38.2] | 43 ±19.0 [19.9–73.4] | 0.001 |

| Delta power (μV2*s) | 195±103 [11–456] | 133±56 [56–231] | 0.025 |

| Cerebrospinal fluid | |||

| Aβ40 (pg/mL) | 11208 ±3420 [6089–16849] | 7900 ±2483 [2909–11729] | 0.003 |

| Aβ42 (pg/mL) | 914 ±224 [514–1494] | 717 ±143 [512–910] | 0.013 |

| Aβ42:Aβ40 ratio | 0.084 ±0.015 [0.04–0.11] | 0.097 ±0.029 [0.08–0.18] | 0.078 |

| Tau (pg/mL) | 221 ±92 [106–504] | 167 ±80 [76–306] | 0.098 |

| pTau181 (pg/mL) | 42 ±14 [23–72] | 32 ±13 [13–52] | 0.054 |

| VILIP-1 (pg/mL) | 144 ±52 [61–275] | 104 ±42 [52–170] | 0.040 |

| Neurogranin (pg/mL) | 2199 ±1135 [650–5063] | 1330 ±814 [436–2787] | 0.039 |

| SNAP-25 (pg/mL) | 4.0 ±1.2 [1.6–6.4] | 3.3 ±0.9 [1.9–4.8] | 0.069 |

| Total protein (mg/mL) | 0.59 ±0.13 [0.33–0.99] | 0.53 ±0.10 [0.34–0.67] | 0.216 |

Demographic, sleep, and cerebrospinal fluid characteristics of control and OSA groups. All continuous data are shown as mean ±standard deviation [range]. OSA = Obstructive sleep apnea. REM = Rapid eye movement sleep. NREM = non-REM sleep. Sleep latency = duration from light out until sleep onset. REM latency = duration from sleep onset until first REM. Sleep efficiency = total sleep time / time in bed. WASO=wake time after sleep onset). PLMI = Periodic limb movement index. Aβ40 = amyloid-β-40. Aβ42=amyloid-β-42. pTau181=phosphorylated Tau-181. VILIP-1 = Visinin-like protein 1. SNAP-25 = Synaptosomal-associated protein 25 kDa.

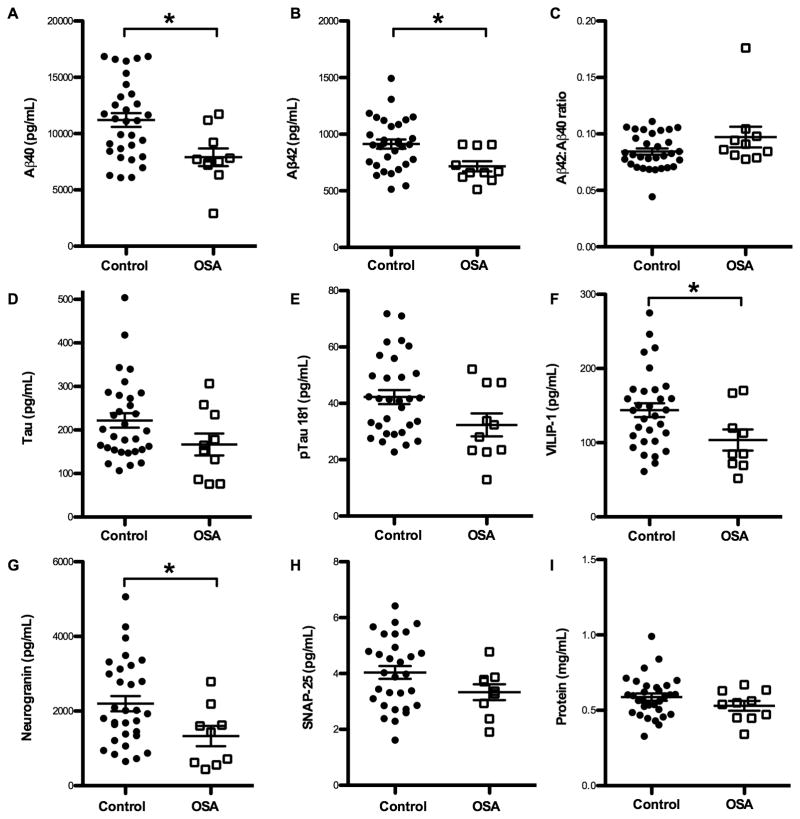

We first tested the hypothesis that higher SWA in control participants is associated with a lower CSF Aβ40. As predicted from animal studies,4,7–8 there was a significant negative correlation between SWA (as measured by delta power) and Aβ40 (Figure 1). We then assessed sleep and Aβ40 in the OSA group. Indeed, the OSA group had decreased delta power compared to the Control group.(Table 1) There were significantly more arousals per hour in the OSA group compared to the Control group, though there were no differences in total sleep time or other sleep variables.(Table 1) Interestingly, there was no significant relationship between SWA and CSF Aβ40 in the OSA group.

Figure 1. Slow wave activity and cerebrospinal fluid Amyloid-β-40.

Slow wave activity, as measured by average delta power during non-rapid eye movement sleep, is negatively correlated with Aβ40 levels in the cerebrospinal fluid the following morning, in the Control group (n=29, Spearman’s r=−0.368, p=0.049). Values from the OSA group (n=10) do not have a significant correlation (Spearman’s r=0.152, p=0.676) and do not follow the same trend as the Control group. Aβ40 = amyloid-β-40. OSA = Obstructive sleep apnea.

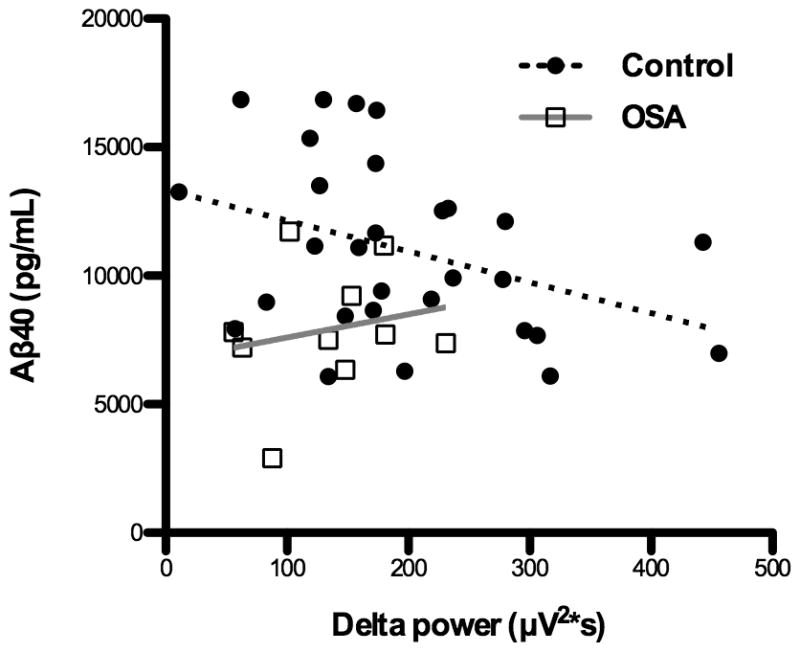

We had hypothesized that Aβ40 would be increased in OSA due to decreased SWA; however, we unexpectedly found that Aβ40 was significantly decreased in the OSA group (Figure 2A). Despite having excluded participants with Aβ42 <500 pg/mL which is a biomarker of amyloid plaques, we assessed additional AD biomarkers. Aβ42 was significantly reduced in the OSA group (Figure 2B); however, this was not due to the presence of amyloid plaques since there was no difference in the Aβ42:Aβ40 ratio (Figure 2C), a more sensitive marker for amyloid plaques.11 Furthermore, Tau and pTau181, which are typically increased in AD,11 were decreased in the OSA group (Figure 2D–E). Neurogranin, SNAP-25, and VILIP-1, all neuronally-derived proteins, were also decreased in the OSA group (p<0.05 for neurogranin and VILIP-1) (Figure 2F–H). Total CSF protein, the majority of which is albumin derived from the blood, was not significantly different between the groups (Figure 2I).

Figure 2. Cerebrospinal fluid Amyloid-β and protein levels.

CSF protein levels are plotted for each individual by group. Mean, standard deviation, and p values are listed in Table 1. Line indicates mean and bars denote standard error. Asterisks indicate p < 0.05. (A) Aβ40 and (B) Aβ42 are significantly lower in OSA compared to Control group. (C) Aβ42:Aβ40, an decrease of which is a sensitive marker of amyloid deposition, was not different between groups. There were strong trends for both (D) Tau and (E) pTau181 being lower in the OSA group. Neuronally-derived proteins (F) VILIP-1 and (G) neurogranin were significantly decreased in the OSA group, and (H) SNAP-25 trended lower also. Total protein (I) was not different between groups. OSA = Obstructive sleep apnea. Aβ40 = amyloid-β-40. Aβ42=amyloid-β-42. pTau181=phosphorylated Tau-181. VILIP-1 = Visinin-like protein 1. SNAP-25 = Synaptosomal-associated protein 25 kDa.

Discussion

To begin to determine how OSA increases AD risk, we tested the hypothetical cascade of OSA causing increased arousals, decreased SWA, and increased Aβ. We did find increased frequency of arousals and decreased SWA in the OSA group. Furthermore, SWA was negatively correlated with CSF Aβ40 among controls, as predicted from animal data.4,8 However, we found no such relationship in the OSA group, and Aβ40 was surprisingly decreased in the OSA group despite having lower SWA compared to controls.

Our finding that CSF Aβ is reduced in OSA is unanticipated given the growing literature on the association of OSA and AD. Our finding contrasts with two rodent studies using chronic intermittent hypoxia, a model of OSA, which showed increased release of Aβ by neurons and increased intracellular Aβ.15–16 Based on similar Aβ42:40 ratios between groups and decreased Tau and pTau181 levels in the OSA group, it is unlikely that decreased Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels in the OSA group are due to sink effects of existing amyloid plaques in the OSA group. We propose potential mechanisms that may explain our unexpected finding.

Since all assessed neuronally-derived proteins were decreased in the OSA group, yet CSF total protein (predominantly albumin from blood) was no different from controls, we favor the possibility that OSA affects the interaction between CSF and ISF. The glymphatic system promotes solute exchange between CSF and ISF,8,17 and respiration-related pressure cycling helps propel the flow of ISF to CSF in the human glymphatic system.18 During an obstructive apnea, respiratory effort against a closed airway creates elevated intrathoracic and intracranial pressure, and a sudden pressure reversal at the end of the apnea. Repetitive high pressure fluctuations may impede the glymphatic flow of metabolites from ISF into CSF.7,18 This would result in higher concentrations of Aβ and other neuronally-derived metabolites lingering in the ISF rather than being transported into the CSF, resulting acutely in lower CSF concentrations. Another potential mechanism involves the clearance of subarachnoid CSF directly into dural lymphatic channels.19 Due to recurrent hypoxia and subsequent right heart strain, venous pressure is typically elevated in OSA. Therefore, there may be more resistance to CSF clearance via direct lymphatic drainage, leading to a relative dilution of solutes in the CSF that originated in the ISF.

It is possible that the decreased CSF Aβ levels in OSA reflect truly decreased ISF Aβ levels. For instance, while we examined SWA during sleep, EEG slowing present during wakefulness in OSA20 may increase total SWA over the 24-hour period, subsequently leading to decreased Aβ levels. Another possibility is that hypoxia in OSA reduces neuronal activity, leading to less Aβ release. In a pig model, there was decreased Aβ42 in CSF following hypoxia.21 However, in several different models, hypoxia is associated with increased Aβ,15–16 through increased expression of β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme,22 decreased degradation by neprilysin,23 increased intracellular transport of APP,24 and potentially other mechanisms. Therefore hypoxia associated with OSA is predicted to increase ISF Aβ, even in the setting of decreased neuronal activity. Moreover, all neuronally-derived proteins that we assessed—including those with long half-lives such as Tau, or those related to neuronal injury such as VILIP-1—were decreased in the OSA group. A global reduction in neuronally-derived proteins argues against the decreased Aβ levels resulting from increased SWA or reduced neuronal activity.

Strengths of this study include controlling for potential confounders, confirming circadian timing by actigraphy, and CSF collection within a 30-minute window. A weakness of the study is the small size of the OSA group. Even with a small OSA group, we found significant reductions in Aβ and other neuronal proteins, indicating a strong effect size. Further studies assessing the effect of arousals and hypoxia on ISF Aβ and other proteins, ISF-CSF exchange, and CSF circulation will be necessary to shed light on the mechanisms underlying this finding.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institutes of Health awards K23-NS089922, UL1RR024992 Sub-Award KL2 TR000450, P01-AG026276 (JC Morris, PI), P01-NS074969, and P01-AG03991 (JC Morris, PI); the J.P.B Foundation; and the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1TR000448 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

- Conception and design of the study: YSJ, DMH.

- Acquisition and analysis of data: YSJ, MBF, CLS, EMH, GMJ, JHL, DLC, AMF, DMH.

- Drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures: YSJ, JHL, EMH, MBF, AMF, DMH.

Potential Conflicts of Interest:

JHL is a co-author of patents involving the use of brain biomarkers, including VILIP-1, SNAP-25, and neurogranin. The patents cover the measurement of these markers in body fluids. These patents are managed by Washington University in accordance with university policies. YSJ, MBF, CLS, EMH, GMJ, DLC, AMF, and DMH have nothing to report.

References

- 1.Yaffe K, Laffan AM, Harrison SL, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing, hypoxia, and risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in older women. JAMA. 2011;306:613–619. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackwell T, Yaffe K, Laffan A, et al. Associations between sleep-disordered breathing, nocturnal hypoxemia, and subsequent cognitive decline in older community-dwelling men: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Sleep Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:453–461. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang Y, Potter R, Sigurdson W, et al. Effects of age and amyloid deposition on Aβ dynamics in the human central nervous system. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:51–58. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang JE, Lim MM, Bateman RJ, et al. Amyloid-beta dynamics are regulated by orexin and the sleep-wake cycle. Science. 2009;326:1005–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.1180962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nir Y, Staba RJ, Andrillon T, et al. Regional slow waves and spindles in human sleep. Neuron. 2011;70(1):153–169. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maquet P, Dive D, Salmon E, et al. Cerebral glucose utilization during sleep-wake cycle in man determined by positron emission tomography and [18F]2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose method. Brain Res. 1990;513:136–143. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bero AW, Yan P, Roh JH, et al. Neuronal activity regulates the regional vulnerability to amyloid-beta deposition. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:750–756. doi: 10.1038/nn.2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie L, Kang H, Xu Q, et al. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science. 2013;342(6156):373–377. doi: 10.1126/science.1241224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ooms S, Overeem S, Besse K, et al. Effect of 1 night of total sleep deprivation on cerebrospinal fluid β-amyloid 42 in healthy middle-aged men: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:971–977. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iber C American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sutphen CL, Jasielec MS, Shah AR, et al. Longitudinal Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarker Changes in Preclinical Alzheimer Disease During Middle Age. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:1029–1042. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kester MI, Teunissen CE, Crimmins DL, et al. Neurogranin as a Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarker for Synaptic Loss in Symptomatic Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:1275–1280. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ju YS, McLeland JS, Toedebusch CD, et al. Sleep quality and preclinical Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurology. 2013;70:587–593. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ju YS, Lucey BP, Holtzman DM. Sleep and Alzheimer Disease pathology – a bidirectional relationship. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2014;10:115–119. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ng KM, Lau CF, Fung ML. Melatonin reduces hippocampal beta-amyloid generation in rats exposed to chronic intermittent hypoxia. Brain Res. 2010;1354:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shiota S, Takekawa H, Matsumoto SE, et al. Chronic intermittent hypoxia/reoxygenation facilitate amyloid-β generation in mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;37(2):325–333. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eide PK, Ringstad G. MRI with intrathecal MRI gadolinium contrast medium administration: a possible method to assess glymphatic function in human brain. Acta Radiologica Open. 2015;4(11):1–5. doi: 10.1177/2058460115609635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiviniemi V, Wang X, Korhonen V, et al. Ultra-fast magnetic resonance encephalography of physiological brain activity – Glymphatic pulsation mechanisms? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0271678X15622047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aspelund A, Antila S, Proulx ST, et al. A dural lymphatic vascular system that drains brain interstitial fluid and macromolecules. J Exp Med. 2015;212:991–999. doi: 10.1084/jem.20142290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D’Rozario AL, Kim JW, Wong KK, et al. A new EEG biomarker of neurobehavioural impairment and sleepiness in sleep apnea patients and controls during extended wakefulness. Clin Neurophysiol. 2013;124:1605–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benterud T, Pankratov L, Solberg R, et al. Perinatal asphyxia may influence the level of beta-amyloid (1–42) in cerebrospinal fluid: an experimental study on newborn pigs. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X, Zhou K, Wang R, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha)-mediated hypoxia increases BACE1 expression and beta-amyloid generation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:10873–10880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608856200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisk L, Nalivaeva NN, Boyle JP, et al. Effects of hypoxia and oxidative stress on expression of neprilysin in human neuroblastoma cells and rat cortical neurones and astrocytes. Neurochem Res. 2007;32:1741–1748. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9349-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jung S, Nah J, Han J, et al. Dual-specificity phosphatase 26 (DUSP26) stimulates Aβ42 generation by promoting amyloid precursor protein axonal transport during hypoxia. J Neurochem. 2016 doi: 10.1111/jnc.13597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]