Abstract

Objective:

To report on dysphagia as initial sign in a case of anti-IgLON5 syndrome and provide an overview of the current literature.

Methods:

The diagnostic workup included cerebral MRI, fiber optic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) with the FEES tensilon test, a videofluoroscopic swallowing study, evoked potentials and peripheral nerve conduction studies, polysomnography, lumbar puncture, and screening for neural autoantibodies. A systematic review of all published cases of IgLON5 syndrome is provided.

Results:

We report a case of anti-IgLON5 syndrome presenting with slowly progressive neurogenic dysphagia. FEES revealed severe neurogenic dysphagia and bilateral palsy of the vocal cords. Autoantibody screening was positive for IgLON5 IgG (+++, 1:1,000) serum levels but no other known neural autoantibody. Polysomnography was highly suggestive of non-REM parasomnia. Symptoms were partially responsive to immunotherapy.

Conclusions:

Slowly progressive neurogenic dysphagia may occur as initial sign of anti-IgLON5 syndrome highlighting another clinical presentation of this rare disease.

A 77-year-old woman presented to our outpatient dysphagia clinic due to slowly progressive dysphagia for 2 years. Due to her swallowing problems, she had lost nearly 30 kg of her body weight, which was 58 kg at the time of hospital admission (body height: 165 cm; body mass index: 22). Her comorbid conditions were type 2 diabetes and arterial hypertension. Apart from the complaints of dysphagia, clinical examination was normal. Cognition, mood, and sleep were reported to be unimpaired. There was no infection or vaccination preceding the neurologic symptoms.

Investigations.

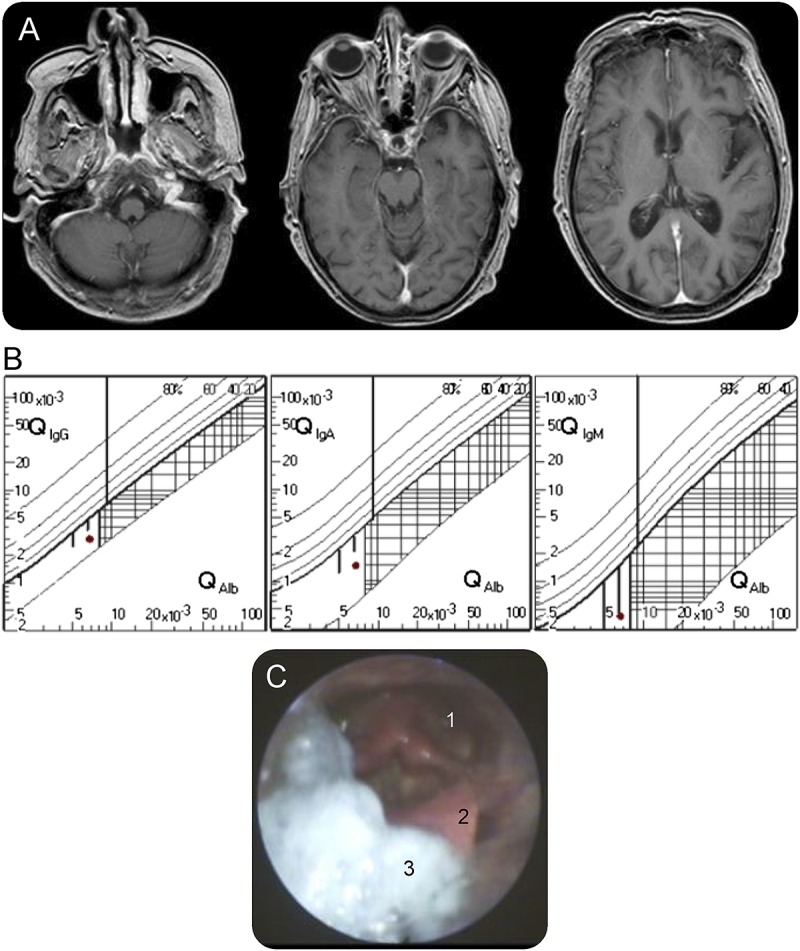

Fiber optic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) revealed severe oropharyngeal dysphagia with poor oral bolus control, premature spillage leading to predeglutitive aspiration, a severely delayed swallowing reflex, and residues in the epiglottic valleculae and in the piriform sinus, with solid and half-solid consistencies tested, leading to postdeglutitive penetration and aspiration (figure, C). The FEES tensilon test showed no improvement of dysphagia.1

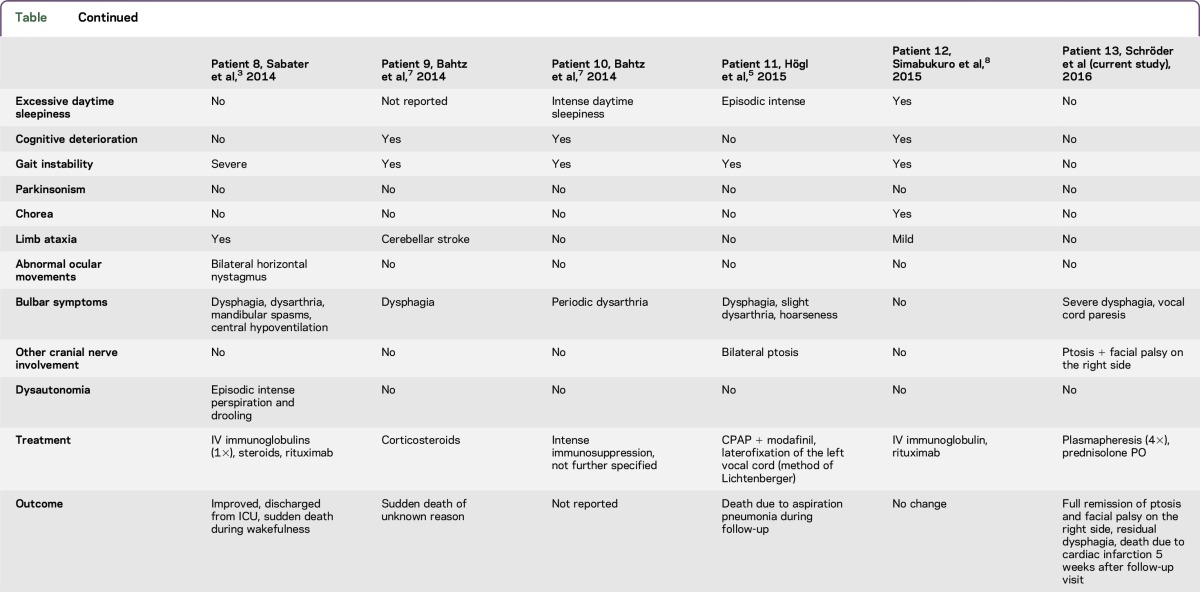

Figure. Investigations.

(A) T1 gadolinium-enhanced axial MRI shows no evidence of underlying brainstem or cranial nerve pathology. (B) No intrathecal immunoglobulin synthesis was observed in CSF analysis using the Reiber scheme. (C) Fiber optic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing reveals postdeglutitive residue in the valleculae epiglotticae (3), on top of the epiglottis (2), and in the piriform sinuses (1).

Videofluoroscopic swallowing study showed poor oral bolus control and, as subsequently confirmed by high-resolution manometry, inadequate opening of the upper esophageal sphincter and ineffective esophageal peristalsis due to disharmonic and partially retrograde contractions. Cerebral MRI (figure, A) including contrast-enhanced high-resolution imaging of brainstem and cranial nerves was unremarkable. EEG was unremarkable. Nerve conduction studies had normal findings. EMG including repetitive nerve stimulation was normal without indication of a myasthenic reaction or myopathy.

Serum acetylcholine receptor antibodies, muscle-specific tyrosine kinase antibodies, and titin antibodies were negative (Euroimmun; Lübeck, Germany). Screening for antiganglioside antibodies was negative. CT examination of the chest and abdomen with contrast agent showed no evidence of malignancy. Moreover, gynecologic examination showed no evidence of an underlying tumor. ECG was normal. Screening for systemic autoimmune diseases and hematologic malignancy was negative. Except for a probably irrelevant decrease in the serum/CSF glucose quotient (0.4, reference value 0.6–0.9), routine CSF analysis was unremarkable. No intrathecal immunoglobulin (Ig) synthesis (figure, B) or isolated oligoclonal IgG bands were observed and accordingly no antibody-producing plasma cells were found in the CSF as revealed by flow cytometry. Autoantibody screening was positive for IgLON5 IgG (+++, 1:1,000) serum levels but no other known neural autoantibody. CSF was not analyzed for the presence of neural autoantibodies. However, as measured by the total IgG ratio between CSF and serum (0.003), relevant CSF titers of IgLON5 IgG can be expected even by passive diffusion.

Sixteen days after admission, right-sided ptosis and peripheral facial palsy occurred, followed by respiratory deterioration necessitating orotracheal intubation and subsequent tracheotomy. Subsequent FEES revealed bilateral vocal cord palsy with complete glottis closure.

Ambulatory polysomnography (PSG) (Somnoscreen; Somnomedics GmbH, Randersacker, Germany) without videography and audiography was conducted in the intensive care unit (ICU). It was applied according to American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) standard criteria (AASM Scoring Manual 2.0)2 including EEG (F4, C4, C3, O2, M1, and M2 electrodes), electro-oculography, EMG (mental, both anterior tibialis muscles), cardiorespiratory recording (single-channel ECG, thoracic and abdominal respiratory movements [piezo], transcutaneous oxygen saturation), and body position. Nasal airflow (thermistor) and nasal pressure cannula were not applied.

Sleep stages and associated events were scored according to suggested definition by Sabater et al.3 At the time of PSG, the patient was tracheotomized, but weaned from mechanical ventilation. For that reason, potential stridor or obstructive sleep apnea syndrome were not assessable.

Sleep efficacy was reduced to 55.1%. Undifferentiated non-REM (NREM) sleep with frequent movement artifacts occurred during the first and second third of the night associated with recurring arousals with and without association with partly highly frequent periodic limb movements (92.2/h). Periodic limb movements were also present in wakefulness (95.2/h). Normal slow wave sleep, predominantly occurring in the last third of the night, was associated with frequent spindles. It was regularly fragmented by leg movements. REM sleep was reduced (1.5%) and showed bursts of muscle activity in mentalis and tibial anterior muscles, compatible with REM sleep without atonia. Respiratory parameters were normal (apnea hypopnea index 0.9/h, oxygen desaturation index 0.2/h, mean oxygen saturation 98%, minimal oxygen saturation 91%, breathing frequency 17/min).

Due to the absence of video recordings, REM sleep behavior disorder or purposeful behaviors were not assessable but recurrent motoric artifacts especially during undifferentiated NREM might be suspicious for possible behavior during REM and NREM sleep.

Due to the detection of IgLON5 IgG, an immune-mediated neuropathy of the cranial nerves or brainstem pathology was suspected and a total of 5 cycles of plasmapheresis (treatment of 1.5 plasma volumes every other day) combined with IV methylprednisolone pulse therapy (1 g/d for 5 consecutive days) was initiated. This treatment led to mild improvement of vocal cord paresis and marked remission of ptosis and facial nerve palsy.

Hence, immunosuppressive therapy was continued with oral glucocorticoids (80 mg prednisolone). After the patient was weaned from the respirator, FEES revealed that although vocal cord paresis showed further improvement, severe pharyngeal dysphagia persisted. The patient was transferred to a rehabilitation unit with a tracheal cannula in place without any oral intake. Nutrition was given via percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube.

At a follow-up visit 6 weeks later, dysphonia had substantially improved. Speaking was loud and clear when the cuff was deflated and the cannula was manually closed. FEES revealed that vocal cord paralysis had resolved and the patient was able to swallow her saliva without any problems. When given small amounts of liquids, the swallowing reflex was triggered; however, the whiteout was shortened and weak, corresponding to a reduced laryngeal elevation and weak pharyngeal contraction. Following our standard decannulation protocol, the tracheal cannula was removed.4 Swallowing training started with small amounts of pudding textures, while nutrition was supplied by tube feeding. Treatment with prednisolone was tapered below Cushing threshold. No relapses of ptosis, facial nerve palsy, or other focal neurologic deficit were observed. The patient died unexpectedly 5 weeks later. A few days earlier, the patient had again developed an aggravated stridor.

DISCUSSION

We present a case of a 77-year-old woman with slowly progressive neurogenic dysphagia as initial sign of anti-IgLON5 syndrome. During the hospital stay, multiple cranial nerves, either peripheral or central portions, were affected, leading to ptosis and facial nerve palsy on the right side. Intubation was necessary due to bilateral vocal cord paresis and severe dysphagia. Instrumental dysphagia assessment revealed a complex pathophysiology involving the oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal phase of swallowing.

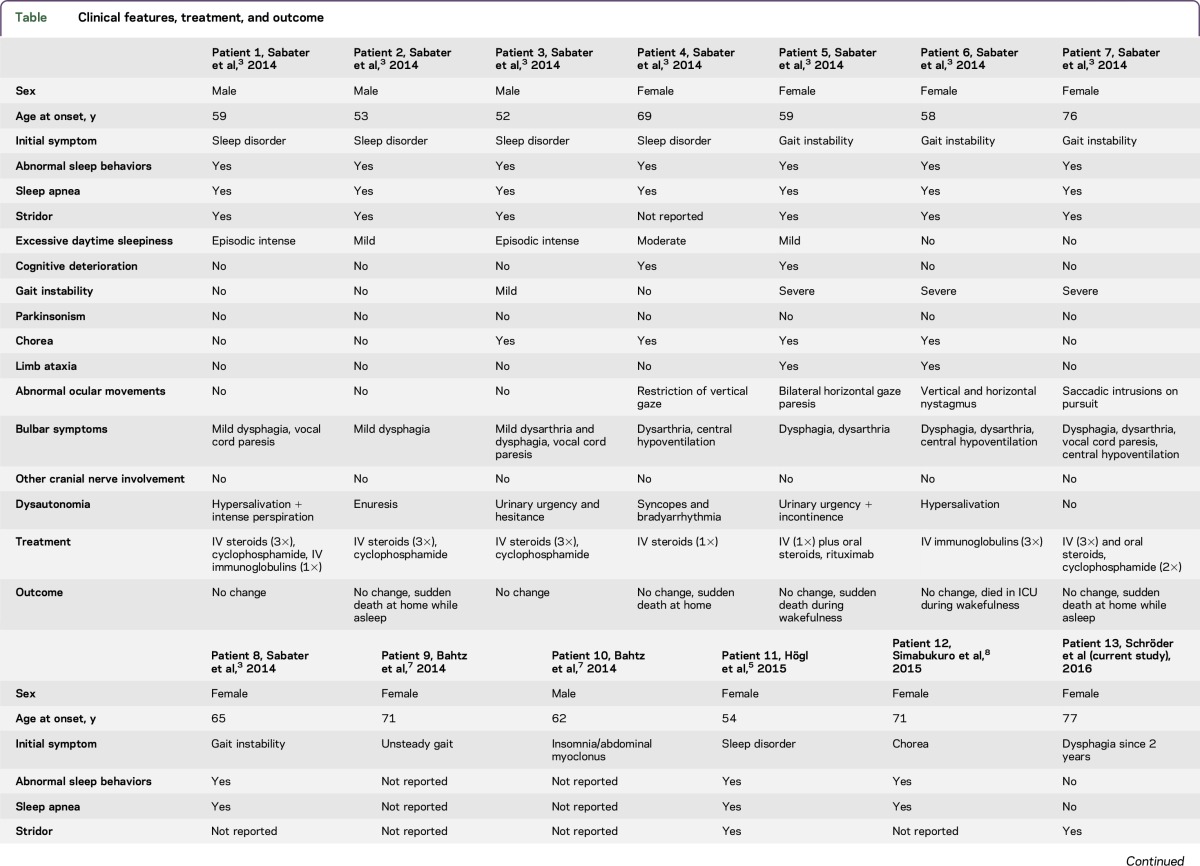

The first case series of 8 patients with anti-IgLON5 syndrome was published in 2014.3 Common clinical manifestation was NREM or REM parasomnia with sleep breathing disorder. Since then, 4 additional cases have been published (table), all of which developed sleep abnormalities initially or during the course of the disease. None of the patients presented initially with bulbar symptoms, whereas 10 of 12 patients developed neurogenic dysphagia during the course of the disease. A patient with cranial nerve pathology evidenced by a bilateral ptosis was first reported in 2015.5 An overview of the clinical characteristics is provided in the table including published cases of anti-IgLON5 syndrome until the present day.

Table.

Clinical features, treatment, and outcome

In contrast to all other published cases, the patient presented here did not show any of the previously reported symptoms, such as gait instability or chorea. PSG conducted in the ICU revealed reduced sleep efficiency and the abnormal sleep architecture in NREM and REM sleep typically described in the anti-IgLON5 syndrome.3 Video recording was not available to assess abnormal behaviors during NREM or REM sleep.

With regards to treatment options, IV immunoglobulins were applied in 4/13 patients, IV steroids in 9/13 patients, and rituximab in 3/13 patients. Transient clinical improvement has only been reported in one case.3 In the case presented here, antibody depletion via plasmapheresis combined with immunosuppressive glucocorticoid therapy led to complete remission of ptosis, vocal cord paresis, and facial palsy, as well as partial remission of neurogenic dysphagia, making removal of the tracheal cannula possible during a follow-up visit.

Taken together, the exact role of IgLON5 IgG in the pathogenesis of the clinical presentations remains unclear.6 IgLON5 is a neuronal cell adhesion molecule predominantly expressed in the adult and developing CNS but expression by peripheral nerve or skeletal or smooth muscle has not been reported so far.6 Expression of IgLON5 on cranial nerve has not been studied until now. The patients described so far have a broad variety of neurologic deficits as well as a heterogeneous disease course. Treatment with immunosuppressants did not lead to sustained improvement in the majority of the published cases.

A suboptimal PSG, lack of confirmatory antibody testing, and the absence of HLA studies are limitations of this study. The exact circumstances of the patient's death remain unclear. The patient may have died before the syndrome had developed fully.

In the patient described, the course of the disease and, in particular, the complete remission of most of the symptoms following antibody-depleting treatment may support the hypothesis of antibody-mediated effects as part of the underlying pathophysiology. Anti-IgLON5 syndrome constitutes another rare differential diagnosis in patients presenting with isolated slowly progressive neurogenic dysphagia.

GLOSSARY

- AASM

American Academy of Sleep Medicine

- FEES

fiber optic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing

- ICU

intensive care unit

- Ig

immunoglobulin

- NREM

non-REM

- PSG

polysomnography

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Schröder: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation. Dr. Melzer: analysis and interpretation, acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Ruck: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Heidbreder: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation. Dr. Kleffner: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Dittrich: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Muhle: acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Warnecke: analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Prof. Dziewas: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, study supervision.

STUDY FUNDING

No targeted funding.

DISCLOSURE

J.B. Schröder received speaker honoraria from Abbvie Inc. N. Melzer received travel funding and/or speaker honoraria from Biogen Idec, GlaxoSmithKline, Teva, and Fresenius Medical Care; spends 5% of his time performing immunoadsorption; and received research support from Fresenius Medical Care and Diamed. T. Ruck received travel funding and/or speaker honoraria from Genzyme, Novartis, Biogen, and Teva; and received research support from Genzyme and Novartis. A. Heidbreder received travel funding and/or speaker honoraria from Air Liquide, Vital Air, Heinen+Loewenstein, and UCB. I. Kleffner received travel funding and/or speaker honoraria from CSL Behring and received research support from IMF. R. Dittrich received research support from the European Union. P. Muhle received speaker honoraria from Olympus GmbH. T. Warnecke received speaker honoraria from Abbvie, Teva, Bayer, Zamboon, and UCB; and consulted for Abbvie and UCB. R. Dziewas served on the scientific advisory board for Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, BMS, Bayer Healthcare, Daiichi Sankyo, Nestle Health Science, Nutricia, Fresenius, and InfectoPharm; received travel funding and/or speaker honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, BMS, Bayer Healthcare, Daiichi Sankyo, Nestle Health Science, Nutricia, Fresenius, and InfectoPharm; and received research support from the German Research Foundation. Go to Neurology.org/nn for full disclosure forms.

REFERENCES

- 1.Warnecke T, Teismann I, Zimmermann J, et al. . Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing with simultaneous tensilon application in diagnosis and therapy of myasthenia gravis. J Neurol 2008;255:224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berry R, Brooks R, Gamaldo CE, et al. . The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications, for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, version 2.0. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sabater L, Gaig C, Gelpi E, et al. . A novel non-rapid-eye movement and rapid-eye-movement parasomnia with sleep breathing disorder associated with antibodies to IgLON5: a case series, characterisation of the antigen, and post-mortem study. Lancet Neurol 2014;13:575–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warnecke T, Suntrup S, Teismann I, et al. . Standardized endoscopic swallowing evaluation for tracheostomy decannulation in critically ill neurologic patients. Crit Care Med 2013;41:1728–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Högl B, Heidbreder A, Santamaria J, et al. . IgLON5 autoimmunity and abnormal behaviours during sleep. Lancet 2015;385:1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balint Bhatia K. Friend or foe? IgLON5 antibodies in a novel tauopathy with prominent sleep movement disorder, ataxia, and chorea. Mov Disord 2014;29:989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bahtz R, Teegen B, Borowski K, et al. . Autoantibodies against IgLON5: two new cases. J Neuroimmunol 2014;275:8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simabukuro M, Sabater L, Adoni T, et al. . Sleep disorder, chorea, and dementia associated with IgLON5 antibodies. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2015;2:e136. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]