Abstract

Acute psychological stress affects each of us in our daily lives and is increasingly a topic of discussion for its role in mental illness, aging, cognition, and overall health. Better understanding of how such stress affects the body and mind could contribute to the development of more effective clinical interventions and prevention practices. Over the past three decades, the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) has been widely used to induce acute stress in a laboratory setting based on the principles of social evaluative threat - namely, a judged speech-making task. A comparable alternative task may expand options for examining acute stress in a controlled laboratory setting. Here, we used a within-subjects design to examine healthy adult participants’ (n=20 men, n=20 women) subjective stress and salivary cortisol responses to the standard TSST (involving public speaking and math) and the newly created Iowa Singing Social Stress Test (I-SSST). The I-SSST is similar to the TSST, but with a new twist: public singing. Results indicate that men and women reported similarly high levels of subjective stress in response to both tasks. However, men and women demonstrated different cortisol responses: men showed a robust response to both tasks, and women displayed a smaller response. These findings are consistent with previous literature, and further underscore the importance of examining possible sex differences throughout various phases of research, including design, analysis, and interpretation of results. Furthermore, this nascent examination of the I-SSST suggests a possible alternative for inducing stress in the laboratory.

Keywords: sex differences, music performance anxiety, acute stress induction, TSST, I-SSST

Graphical Abstract

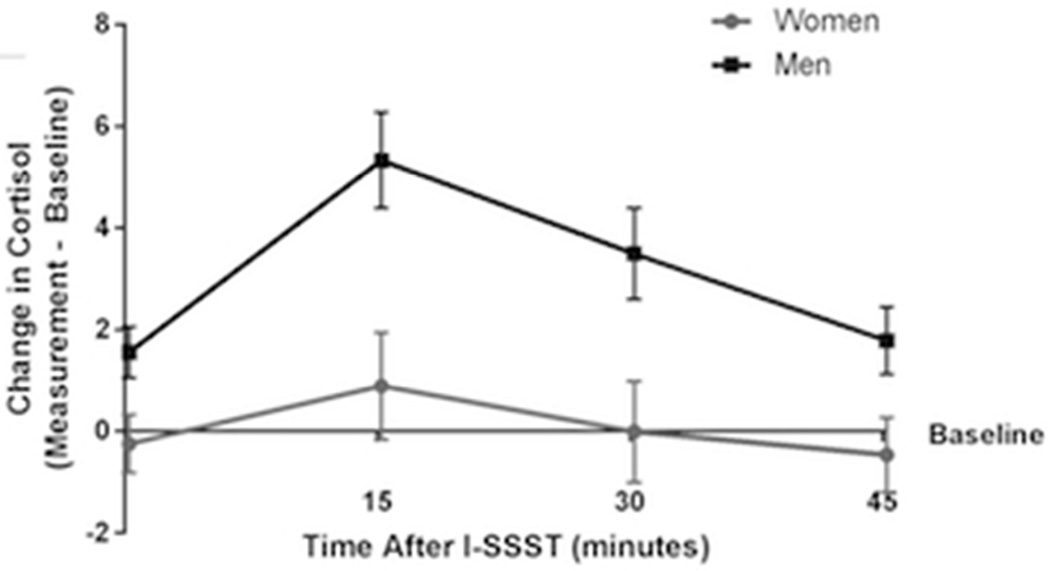

Mean change in salivary cortisol (nmol/L) from baseline over time after the Iowa Singing Social Stress Test (I-SSST) for women (gray circles) and men (black squares; n = 36). Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. The figure presents untransformed change values, while the reported analysis in text used natural log transformed data.

Graphical Abstract

The Iowa Singing Social Stress Test - a novel, musical stress task - elicited responses similar to those induced by the Trier Social Stress Test. We found a robust sex difference in cortisol response yet no sex difference in subjective stress. Our results suggest an alternative acute stress induction method.

Introduction

Acute psychological stress is hugely prevalent, perhaps especially so in Western society where the pace of life has intensified in recent decades. Many commonplace situations evoke stress: relationships, finances, and health, to name a few. When we perceive such circumstances as stressful, a complex cascade of subjective feelings, arousal, and neuroendocrine responses occur (Gillies & McArthur, 2010). In moderate doses, stress facilitates our adaptation to the environment and promotes wellbeing. Our modern lifestyle, however, engenders acute stress responses to a health-prohibitive frequency (American Psychological Association, 2015).

Unraveling the effects of stress on various biopsychosocial functions informs our understanding of its role in the health-illness continuum. Systematic examination of stress can reveal its impact on memory (Lupien et al., 2005; Wolf, 2009) and neuropsychiatric disorders (Southwick et al., 2005), and elucidate its relationship with development (Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007), aging (Lupien et al., 2005), and wellness (Vitetta et al., 2005). Furthermore, stress research contributes to the development of clinical interventions and health recommendations (Southwick et al., 2005; Wolf, 2009). A reliable way to induce acute stress in a controlled laboratory setting is essential to scientific progress in understanding the broader impacts of stress on human life.

The Trier Social Stress Test (TSST; Kirschbaum et al., 1993) has been widely implemented in laboratory-based acute stress experiments (Birkett, 2011; Kudielka et al., 2007) and consists of a performance (impromptu speech and mental arithmetic), evaluation by confederate judges, and uncontrollability (Kirschbaum et al., 1993). The TSST elicits acute physiological and subjective stress responses in approximately 70–80% of adults (Allen et al., 2014; Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004; Kudielka et al., 2007) via a triumvirate of conditions that trigger a significant hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis response: motivated performance, social evaluation, and uncontrollability (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004; Kirschbaum et al., 1993; Kudielka et al., 2007). However, a 70–80% response rate suggests that one-quarter of participants in a given study may not respond to the TSST. Furthermore, habituation to this stress induction protocol has been described (Kudielka et al., 2006; Schommer et al., 2003). Incorporating a different, widely acknowledged performance stressor that similarly employs these three elements while minimizing the creative, somewhat abstract element of speech-writing within a role-play scenario could provide an alternative means to induce feelings of stress and elicit an HPA axis response. Such an alternative may be useful in lines of research in which repeated stress elicitation is desired, when a limited participant pool is available to a laboratory, or with participants for whom a role-play or impromptu speech scenario may impede the desired outcome.

Musicians raised in the Western music tradition commonly experience acute performance anxiety (Kenny, 2011). Estimates suggest that 25–50% of professional symphony members, opera singers, and collegiate musicians experience severe music performance anxiety that diminishes performance quality (Kenny, 2011). As in other performance contexts with inherent social evaluation (e.g., public speaking, acting), vocalists and instrumentalists experience significant subjective and physiological stress responses to both individual and group music performances, and interestingly, such performance anxiety occurs regardless of expertise (Beck et al., 2000; Boyle et al., 2013; Pilger et al., 2014; Yoshie et al., 2009; for a discussion of how experience may mediate performance anxiety, see Sârbescu & Dorgo, 2014). Music performance anxiety appears to begin in childhood and adolescence (Kenny, 2011) and varies on a continuum from low-stress group rehearsals to high-stress solo performances (Fancourt et al., 2015; Fredrikson & Gunnarsson, 1992; Nicholson et al., 2015). The frequency and intensity with which stress responses occur in music performance contexts suggest that a solo singing performance could provide an apt substitute for the impromptu speech component of the TSST for acute laboratory stress induction.

Before entertaining such an alternative to the TSST, one should acknowledge sex differences in neuroendocrine response to this task. First, the HPA axis is influenced by sex hormones, particularly estrogen (Gillies & McArthur, 2010), which can modify stress responsiveness via its regulation of cortisol receptors (Oldehinkel & Bouma, 2011). Second, while a meta-analysis by Dickerson and Kemeny (2004) concluded that biological sex and other innate differences are not strong predictors of acute laboratory stress responses, others have documented that uncontrollable social-evaluative performance, namely the TSST, evokes a more robust cortisol response in men than women (Gillies & McArthur, 2010; Kudielka & Kirschbaum, 2005; Oldehinkel & Bouma, 2011). Monthly hormonal variation (i.e., menstruation) and oral contraceptive use can further impact women’s cortisol response, though such factors are often not accounted for in the literature (Gillies & McArthur, 2010; Kudielka et al., 2007). The differential availability of cortisol in saliva versus plasma measures of cortisol may further account for discrepant findings regarding sex differences (Kirschbaum et al., 1999). Finally, patterns of cortisol reactivity appear to persist independently of subjective stress responses (Gillies & McArthur, 2010; for a discussion of the role of subjective experiences of shame in HPA axis response, see Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004). Thus, simply feeling stressed does not appear to directly correlate with elevated cortisol per se, and response to a stress task that is comparable to the TSST will likely depend in part on sex.

Our goal in the study reported here was to develop a viable alternative to the TSST for inducing acute psychological stress in a laboratory setting and to examine the extent to which the aforementioned sex differences extend to a novel singing task. We directly compared the TSST to the Iowa Singing Social Stress Test (I-SSST), using a within-subjects design, and evaluated the relative effectiveness of the two tasks at eliciting subjective and physiological stress in men and women. The I-SSST consists of the same components as the TSST; however, the speech is replaced by singing. While women self-report music performance anxiety more frequently than men (Kenny, 2011), to our knowledge sex differences in HPA axis responsivity (e.g., cortisol) have not been systematically examined in regards to music performance anxiety. Given the similarities in motivated performance, social evaluation, and uncontrollability between the I-SSST and the TSST, we anticipated that sex differences in cortisol responses to these tasks would align with those previously described in TSST research (Gillies & McArthur, 2010; Kudielka & Kirschbaum, 2005; Oldehinkel & Bouma, 2011). Specifically, based on extant literature, we predicted: (1) the I-SSST would elicit comparable elevation in subjective stress and salivary cortisol as the TSST, and (2) that men and women would show different cortisol response patterns, regardless of condition.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The Institutional Review Board at The University of Iowa approved this study, and all participants provided written informed consent. Forty-five healthy English-speaking volunteers (n = 21 men) participated in this two-day study for monetary compensation; all were recruited via a University-wide email system. One man and one woman withdrew after receiving singing instructions, and three women did not return for their second study visit (one completed singing, two completed the speech). The 40 participants (n = 20 men) who completed the study were well-matched across the two sexes for age (men M = 31.50 years, SEM = 2.76; women M = 32.70 years, SEM = 3.38) and education (Years of education: men M = 16.39, SEM = 0.92, n = 18; women M = 15.42, SEM = 0.55, n= 19). Most participants were Caucasian (75%). We excluded individuals with mental illness, smokers, nightshift workers, and those pregnant or breastfeeding, as well as musicians (i.e., current performers and/or teachers) and those with performance experience (e.g., karaoke hobbyists, actors). Of the over 400 individuals who expressed interest in our study, such criteria rarely led to exclusion; most were placed on a waiting list. Disinterest upon learning of the study’s deception component or presence of an anxiety disorder were the most common reasons for non-participation.

Because phase of menstrual cycle and hormonal contraceptive use (e.g., oral, intrauterine, injection) can impact women’s cortisol response (Gillies & McArthur, 2010; Kudielka et al., 2007), we collected start date of most recent menstruation and hormonal contraceptive information for each visit. The women (n = 20) were: using hormonal contraceptives (n = 9), not using hormonal contraceptives (n = 8), or postmenopausal/perimenopausal (n = 3). Four women were removed from cortisol analyses (see Statistical Analysis section for details). Women’s menstrual cycle phase during the TSST (n = 16) consisted of: using hormonal contraceptives (n = 8), in the follicular phase (n = 6), and postmenopausal (n = 2). There was no significant difference across these groups of women in the cortisol area under the curve increase (AUCi) on the TSST day, F(2,13) = 0.46; n = 16; p = .640; pη2 = .066. During the I-SSST (n = 16), women were: using hormonal contraceptives (n = 8), in the follicular phase (n = 1), in the luteal phase (n = 5), and postmenopausal (n = 2). There was no significant difference across these groups of women in AUCi on the I-SSST day, F(3,12) = 0.43; n =16; p = .987; pη2 = .011.

Self-Reported Stress

Participants self-reported their subjective feelings of emotion using two scales: the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988) and a 100-point visual analog scale (VAS). The PANAS consists of two 10-item scales that measure self-reported positive affect (e.g., interested, strong, alert) and negative affect (e.g., irritable, nervous, upset). On the VAS, participants rated how happy, scared, calm, stressed, and irritated they felt, (e.g., for stress) ranging from, “I don’t feel [stressed] at all” (0) to, “I feel extremely [stressed]” (100). Here, we report only on the self-reported stress levels from the VAS, as this is the most direct, parsimonious self-report measure; the other self-report variables were not analyzed for the purposes of the current study and are reported here to facilitate potential replication by other researchers.

Cortisol

We collected saliva samples using SalivaBio Oral Swabs (Salimetrics LLC, State College, Pennsylvania). For each sample, the participant placed the oral swab under his or her tongue where it remained for approximately 2 minutes. Samples were placed in 17 mm x 100 mm storage tubes and stored at −70°C until assayed. Duplicate cortisol testing, including centrifugation, was completed through Salimetrics LLC Testing Services using an ELISA-based immunoassay kit specific for the detection of cortisol. Of 400 samples, 16 were of insufficient quantity to conduct duplicate analysis, and therefore single analysis was used. Nine samples were of insufficient quantity to perform any analysis, and one sample was missing due to experimenter error. Average intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation were less than 5% and 6% respectively. The analytical sensitivity for the cortisol assay used is .007 µg/dL (.193 nmol/L).

Procedure

In this within-subjects experiment, participants completed the TSST and the I-SSST on two days with similar schedules, approximately one week apart. Task order (TSST/I-SSST or I-SSST/TSST) was counterbalanced and randomly assigned by sex across all participants using a random number table, such that an equal number of men and women completed each task order. In order to mimic a naturalistic, social-evaluative stress experience, we deceived participants regarding the study’s purpose and stated that we were examining emotional responses to educational and cultural tasks commonly encountered in a school setting. We also stated that their performance was evaluated, rated against other participants, and video and audio recorded -all of which were only seemingly true. Participants were debriefed at the conclusion of their participation in the study.

Our protocol for the TSST closely followed that described in Birkett (2011) and Kudielka et al. (2007), as did our new protocol: the I-SSST. Participants were instructed to get a sufficient night’s sleep, fast, and avoid caffeine and alcohol the morning prior to testing. Each participant arrived to our laboratory between 12:00 and 16:00 when cortisol levels are relatively stable (Birkett, 2011; Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004; Kudielka et al., 2007) and confirmed they had followed these instructions. Participants only consumed sips of water during their time at our laboratory to prevent saliva dilution. Participants completed a 45-minute acclimation period in a private testing room where they could read magazines provided by the experimenter. The consent process was completed and demographic information was collected on day one and accounted for approximately 15- to 20-minutes of the acclimation period; previously collected demographic information was reviewed briefly (approximately 10-minutes of the acclimation period) on day two.

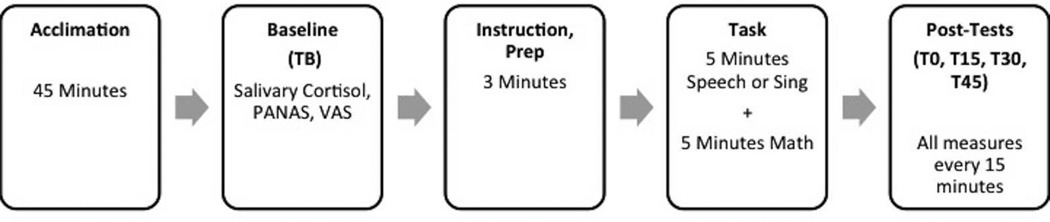

Following the acclimation period, we collected a baseline saliva sample and the participant completed self-report measures (time baseline, TB). The experimenter then provided task instructions (either for the TSST or the I-SSST). Following three-minutes of task preparation, the experimenter walked the participant to the judging room where s/he completed that day’s task (approximately 11-minutes total duration). Immediately after the task, the experimenter walked the participant back to the testing room (< 30-seconds walk) with minimal interaction (no eye contact; “We will now return to the first room.”). Here, the participant completed salivary cortisol and self-report measures (time 0-minutes, T0), and again at 15-, 30-, and 45-minutes post (T15, T30, and T40 respectively). With the exception of these repeated measures, the participant sat quietly alone in the testing room for the entire post-task duration. This procedure is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Visual representation of the timeline followed to administer the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) and the Iowa Singing Social Stress Test (I-SSST).

Experimenter Roles

All role-playing individuals donned white laboratory coats for the experiment and utilized scripted instructions. Two authors (AERH and ABE, both women) performed the experimenter role (E1), which consisted of the consent process, deception, instruction, and data collection. Confederates (C1 and C2, nearly always a man and a woman) pretended to be either speech or vocal performance expert judges and were trained by the first author to maintain a serious facial expression and authoritative speech prosody, make eye contact with the participant, and take notes during the task (as outlined in Birkett, 2011 and Kudielka et al., 2007). For fewer than 5% of the total number of judging sessions, a man and a woman were unavailable to fill the roles of C1 and C2, and therefore, both judges were the same sex. In two cases, only one judge was available: a man in the first case and a woman in the second case (see Allen et al., 2014 for more information regarding the importance of considering judges’ sex in the TSST).

Description of the TSST and I-SSST Tasks

On the TSST day, E1 instructed participants to prepare a five-minute speech describing their personal qualifications for their dream job (note that in an alternate version of the TSST, not used here, participants imagine they are accused of shoplifting and must invent an explanation of their innocence). Participants could make notes during the three-minute preparation period but were not allowed to use notes during the actual speech-making task.

On the I-SSST day, E1 informed participants they would complete a music skills evaluation that consisted of singing for judges for five minutes. Participants were provided a seven-page packet (available from the first author) with lyrics to numerous folk (e.g., This Land is Your Land), children’s (e.g., Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star), older pop (e.g., Dancing Queen), and country (e.g., I Walk the Line) songs. For the three-minute preparation period, participants were told to vocally warm up and peruse the song packet. During the actual singing task, participants were instructed to sing as many or as few songs from the packet as desired to best showcase their music performance skills.

Following the speech or singing, participants performed mental subtraction aloud for five minutes (e.g., serially subtract 13 from 1022). When a participant erred, C1 stated, "That is incorrect. Begin again.” During the speech, singing, and math tasks, participants were seemingly video and audio recorded: a microphone and video camera were set up for show and appeared to be connected to a computer. Judges sat behind a large table a few feet from the participant and used a stopwatch to ensure accurate timekeeping. If needed, C1 prompted the participant to continue speaking or singing; C1 also informed participants when to begin the math task. At the end of the task, C1 instructed the participant to stop and leave the room. C2 remained silent and pretended to operate the equipment. The setup of the judging room is displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Mock setup of the judging room for the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) and the Iowa Singing Social Stress Test (I-SSST). Note that those pictured are not actual participants.

Statistical Analysis

Change scores were used to examine how cortisol and self-reported stress changed over time. Change scores were calculated by subtracting the value at TB from each time point of interest (T0, T15, T30, and T45). We reference these change scores by the point of interest (see Figure 1). Change in cortisol from baseline was not normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk < 9.34, ps < .05 for 6 of 8 dependent measures) and was therefore natural log transformed, with a constant of 6 added to each cortisol change score to remove negative values. Change in self-reported stress from baseline was normally distributed.

Change scores for cortisol and self-reported stress were analyzed using 2 condition (TSST, I-SSST) by 2 sex (Men, Women) by 4 time (T0, T15, T30, and T45) mixed ANOVAs. Follow-up tests were conducted with Bonferroni correction. Mauchly’s test indicated a violation of the sphericity assumption for change in self-reported stress (Time: ε = .554; Condition X Time: ε = .818) and change in cortisol (Time: ε = .600; Condition X Time: ε = .642), therefore a Greenhouse-Geisser kluge was applied.

As in similar previous research, we excluded cortisol non-responders from our analyses (Buchanan & Tranel, 2008; Kirschbaum et al., 1993; Miller et al., 2013). A cortisol non-response is defined here as a decrease in cortisol from TB to T15 (Buchanan & Tranel, 2008). Table I shows the rates of cortisol response in men and women. One man provided insufficient saliva during the TSST to determine his cortisol response for this task, and his data were therefore classified as “non-response” during the TSST. Participants who had a non-response to both the TSST and the I-SSST were labeled non-responders (n = 3, all women) and were excluded from cortisol analyses. One woman did not complete all measures due to experimenter error and was removed from the self-reported stress analysis (n = 39). One woman yielded an extremely high baseline cortisol value on her second visit (I-SSST) relative to all other cortisol values obtained from the experiment across all participants, and her cortisol data were excluded from the cortisol analyses, resulting in usable data from 36 individuals (n = 20 men) for change in cortisol analyses. Four participants (n = 2 men) yielded insufficient saliva quantity for cortisol analysis at one or more time points, therefore values were imputed using corresponding group means. AUCi were calculated for correlational analyses of cortisol data with self-reported stress data (Pruessner et al., 2003). One man was an outlier for AUCi during the TSST (3.7 SD above mean) and was therefore not included in the correlational analyses using AUCi. All participant exclusions are listed in Table I.

Table I.

Description of Cortisol Response and Exclusions from Analyses for Men and Women

| Men (n = 20) | Women (n = 20) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cortisol Response | ||

| Both TSST and I-SSST | 18 | 5 |

| TSST only | 0 | 6 |

| I-SSST only | 2a | 6 |

| Neither | 0 | 3b |

| Exclusions from Self-Report Analyses | ||

| Incomplete data | 0 | 1 |

| Exclusion from Cortisol Change Analysis | ||

| Non-responder | 0 | 3b |

| Major outlier | 0 | 1 |

| Exclusions from AUCi Analyses | ||

| Non-responder | 0 | 3b |

| Major outlier | 1 | 1 |

Note. TSST = Trier Social Stress Test; I-SSST = Iowa Singing Social Stress Test; AUCi = Area Under the Curve Increase.

One man had insufficient saliva quantity to assay cortisol levels during the TSST day and is reported here as having a cortisol response only to the I-SSST.

Three women were classified as non-responders as they did not show a cortisol response to either task. They were removed from all cortisol data analyses.

Results

The response rate for the TSST and the I-SSST in the present study were 72.5% and 77.5%, respectively. Table I reports cortisol response for men and women. Three participants (all women) did not show a cortisol response to either task. Only 25% of women showed a cortisol response to both tasks compared to 90% of men.

Two-tailed independent t-tests were used to examine whether order of tasks influenced variables of interest. The analysis of order effect on self-reported stress change scores at T0 after the TSST showed a violation of Levene’s tests of the assumption for homogeneity of variances (p = .026), therefore a t-test not assuming homogeneous variances was used. There was a statistically significant effect of order on self-reported stress change scores at T0 after the TSST (t(37) = 2.21, n = 39, p = .035). Those who completed the TSST on their first visit (M = 25.25, SEM = 7.47) had significantly greater change in self-reported stress immediately after the task (T0) than those who completed the TSST on their second visit (M = 6.37, SEM = 4.16). There was not a statistically significant effect of order on self-reported stress immediately after the I-SSST (t(37) = −.637, n = 39, p = .528). Order did not have a statistically significant effect on the AUCi for either task (TSST: t(34) = 0.83; n = 36, p = .415; I-SSST: t(34) = −1.21; n = 36, p = .235).

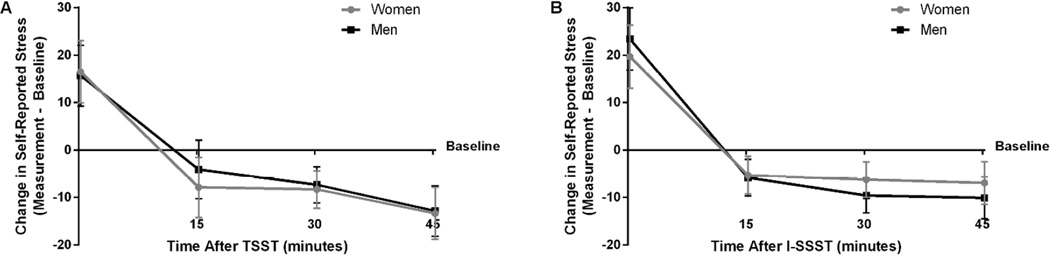

A three-way mixed ANOVA on change in self-reported stress did not show a significant three-way (F(2.46, 90.84) = 0.62; n = 39, p = .571, pη2 = .017; see Figure 3) or two-way interactions (Condition X Sex: F(1, 37) = 0.05, n = 39, p = .823, pη2 = .001; Time X Sex: F(1.66, 61.53) = 0.17, n = 39, p = .803, pη2 = .005; Condition X Time: F(2.46, 90.84) = 1.08, n = 39, p = .355, pη2 = .028). Analysis showed a statistically significant main effect of Time (F(1.66, 61.53) = 49.11, n = 39, p<.001, pη2 = .570), but not of Sex (F(1, 37) < .01, n = 39, p = .974, pη2 < .001) or Condition (F(1, 37) = 0.36, n = 39, p = .551, pη2 = .010). Post-hoc analysis revealed that change in self-reported stress was significantly greater immediately after the task (T0) compared to T15 (p < .001), T30 (p < .001), and T45 (p < .001) post-task. Self-reported stress did not differ between T15 and T30 (p = 1.00), T15 and T45 (p = .061), or T30 and T45(p = .209).

Figure 3.

Mean change in self-reported stress from baseline over time after stress task (n = 39). (A) Change in self-reported stress over time during the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) for women (gray circles) and men (black squares). (B) Change in self-reported stress over time during the Iowa Singing Social Stress Test (I-SSST) for women (gray circles) and men (black squares). Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

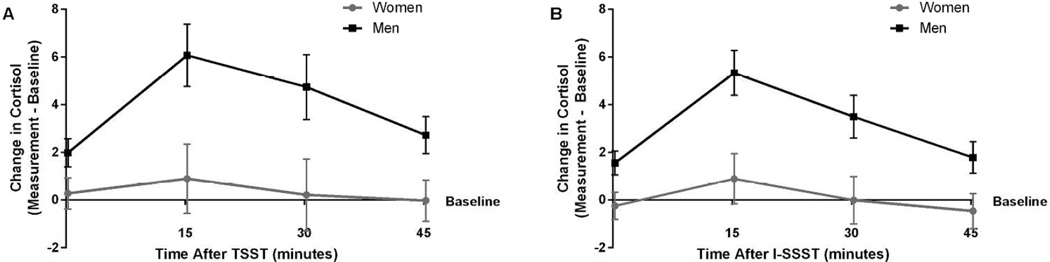

A three-way mixed ANOVA on natural log transformed change in cortisol did not show a significant three-way (F(1.93, 65.53) = 0.37; n = 36, p = .683, pη2 = .011; see Figure 4) or two-way interactions (Condition X Sex: F(1, 34) = 0.14; n = 36, p = .707, pη2 = .004; Time X Sex: F(1.80, 61.17) = 1.39; n = 36, p = .256, pη2 = .039; Condition X Time: F(1.93, 65.53) = 0.38; n = 36, p = .676, pη2 = .011). Analysis showed statistically significant main effects of Time (F(1.80, 61.17) = 9.03; n = 36, p = .001, pη2 = .210) and Sex (F(1, 34) = 43.52; n = 36, p < .001, pη2 = .561) but not Condition (F(1, 34) = 0.21; n = 36, p = .649, pη2 =.006). For the main effect of sex, the change in cortisol was greater for men (M = 2.13, SEM = 0.04 ) than women (M = 1.76, SEM = 0.04). Follow-up tests show change in cortisol was significantly greater at T15 than at T0 (p = .007), T30 (p = .017), and T45 (p < .001) post-task. Change in cortisol at T30 was significantly greater than at T45 post-task (p = .003). Change in cortisol did not differ from T0 and T30 (p = .385) or T0 and T45 (p = 1.00).

Figure 4.

Mean change in salivary cortisol (nmol/L) from baseline over time after stress task (n = 36). (A) Change in salivary cortisol (nmol/L) over time during the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) for women (gray circles) and men (black squares). (B) Change in salivary cortisol (nmol/L) over time during the Iowa Singing Social Stress Test (I-SSST) for women (gray circles) and men (black squares). Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. The figure presents untransformed change values, while the reported analysis in text used natural log transformed data.

The relationship between AUCi for each task was examined with the self-reported stress at T0 for each sex. AUCi for each task was not significantly correlated with self-reported stress change scores at T0 for men (TSST (r = .33, t(17) = 1.44; n = 19, p = .167, r2 = .109; I-SSST (r = .27, t(17) = 1.16; n = 19, p = .260, r2 = .074) or women (TSST (r = .51, t(13) = 2.14; n = 15, p = .052, r2 = .260; I-SSST (r = .07, t(13) = −0.26; n = 15 , p = .801, r2 = .005).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first direct comparison of the TSST to a similar task that employs a singing performance. We predicted: (1) the I-SSST would elicit comparable elevation in subjective stress and salivary cortisol as the TSST, and (2) that men and women would show different cortisol response patterns, regardless of condition. In support of our first hypothesis, the men and women in this study reported increased levels of subjective stress in response to both the “gold standard” acute psychological stress induction method (the TSST) and the new I-SSST. Such responses were immediate and dissipated fairly quickly. In support of our second hypothesis, men and women showed different physiological patterns of response: men exhibited a more robust salivary cortisol response than women after both the singing and the speech tasks. Overall, these results confirm previous findings regarding physiological divergence and subjective similarity in response patterns between men and women (Gillies & McArthur, 2010; Kudielka & Kirschbaum, 2005; Oldehinkel & Bouma, 2011) and further indicate that physiological and subjective stress responses may not have a linear relationship in the context of acute psychological stress that is induced in a laboratory setting (Gillies & McArthur, 2010). As we did not find any significant differences between the two tasks, our findings also indicate that the I-SSST may provide an alternative means for inducing acute psychological stress in a laboratory setting.

Self-Reported Stress

In our sample, men and women reported significantly elevated subjective stress immediately after completing both the TSST and the I-SSST, which aligns with existing evidence (Kudielka et al., 2007). Previous examination of music performance anxiety, however, suggests that women may experience feelings of music performance anxiety to a greater extent and frequency than men (Kenny et al., 2014; Simoens et al., 2015; Sârbescu & Dorgo, 2014). In our study, we included individuals who did not self-identify as professional or semi-professional musicians; specifically, they neither performed regularly nor taught music lessons. While previous research has not, to our knowledge, compared a music performance to another performance-based task such as speech-making, it is possible that a different response pattern between men and women would be found in a sample of musicians, or in a study with a larger sample size. Further, a recent study (Perdomo-Guevara, 2014) posited that not only could the status of musician/non-musician impact one’s adaptive or maladaptive response to performance, but also the musical culture or genre of music performance with which one associates - possible nuanced differences that could become more apparent with a larger sample size, both in self-report measures and physiological measures of stress.

Cortisol Response

The present study yielded three main findings regarding salivary cortisol: (1) men showed a greater increase in cortisol response than women, (2) the peak response for both men and women occurred 15 minutes after the task, and (3) these sex and time effects were obtained in both the standard “speech” and new “singing” versions of the TSST. These sex differences align with existing literature that indicates acute stress via psychological induction imposes a different pattern of response in men and women (Gillies & McArthur, 2010; Kudielka & Kirschbaum, 2005; Oldehinkel & Bouma, 2011). Further, both tasks yielded cortisol response rates similar to those reported in previous research with the TSST (Allen et al., 2014; Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004; Kudielka et al., 2007): 72.5% and 77.5% for the TSST and I-SSST respectively. Our study therefore replicates previous findings and extends research in this area to a novel task built on the same principles as the TSST, and further underscores the need to consider that men and women respond differently to psychological stress. The question remains as to the nature of how these differences occur.

Responses to psychological stressors involve sophisticated coordination of multiple brain regions, neuroendocrine responses, and cognitive and affective processes (Bale & Epperson, 2015; Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Much literature has supported the role of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVA) and anterior pituitary for the mobilization of resources in response to stress (Bale & Epperson, 2015; Selye, 1973; Shirazi et al., 2015). The HPA axis response begins when corticotropic-releasing hormone (CRH) is released from the PVA, which in turn stimulates the anterior pituitary to release ACTH into circulation. ACTH then activates receptors in the adrenal cortex, which results in the synthesis and release of glucocorticoids, notably cortisol (Bale & Epperson, 2015; Selye, 1973). This neuroendocrine cascade is affected by age, sex, and hormonal contraceptive use (Bale & Epperson, 2015) as well as exposure to chronic stress (Bale & Epperson, 2015; Shirazi et al., 2015). It is possible the results of our study were moderated by any one or more of these factors (i.e., age, sex, contraceptive use, chronic stress), which could be explored further in a study of larger scale.

The stress response also includes up- and down-regulation by the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC; Diorio et al., 1993; Buchanan et al., 2010), hippocampus (Buchanan et al., 2009; Shirazi et al., 2015), and amygdala (Adolphs, 2002; Shirazi et al., 2015). The amygdala is known to be involved in emotionally arousing stimuli – particularly fear (Adolphs, 2002) – and is implicated in the expression of CRH during psychological stress (Shirazi et al., 2015). The hippocampus seems to exert a strong influence on the cortisol response (Buchanan et al., 2009) and may be involved in habituation to repeated stress exposure paradigms (Buchanan et al., 2009; Kudielka et al., 2006; Schommer et al., 2003). While we did not find evidence of habituation per se in our study (i.e., there was no effect of order regarding cortisol response, and cortisol responses between the first and second visit were not systematically different), we did find an effect of order regarding self-reported stress for the TSST. Interestingly, an order effect was not found for the I-SSST. Future research could clarify the possible role of habituation and the experience of stress in repeated measures designs with larger samples of men and women.

The mPFC is involved in top-down HPA axis regulation (Buchanan et al., 2010; Diorio et al., 1993; Shirazi et al., 2015), namely stress appraisal. Appraisal refers to how one assesses the severity of the situation or stressor and may explain why two individuals – who, for all intents and purposes, are similar – can respond differently to the same scenario (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). A meta-analysis by Tamres et al. (2002) found that women and individuals who score high on personality measures of neuroticism tend to appraise stressful situations more severely than men and non-neurotic individuals. In our study, men and women reported similar levels of stress, but men showed a significantly more robust cortisol response to both the TSST and the I-SSST compared to women (as in prior research employing the TSST; Kudielka et al., 2007). Some research has suggested that primary appraisal (perceived threat and challenge), but not secondary appraisal (perceived resources to handle the stressor), is a strong predictor of cortisol reactivity (e.g., Gaab et al., 2005; Wirtz et al., 2006); however, such findings appear to have been systematically evaluated only in men. Future research is warranted to determine the extent to which top-down cognitive processes can mediate physiological and psychological responses to acute laboratory stressors in both men and women.

Limitations and Conclusion

Three primary limitations of our study could impact the interpretation and application of our results. First, while our sample was comprised of individuals currently living in the United States who were proficient in the English language, we did not inquire about country of origin or culture. These factors could likely impact stress response dispositions, such as primary and secondary appraisal (Scherer & Brosch, 2009) and how music performance traditions are defined within a culture (Perdomo-Guevara, 2014). Therefore, we cannot draw conclusions regarding possible cultural influence on participants’ responses to the singing (or speaking) tasks. Second, we did not inquire about our participants’ natural dispositions, perform personality measures, or formally inquire about participants’ perception, interpretation, and management of stress -namely, appraisal and coping skills. Future investigations may benefit from inquiring about such traits and allow for more informed judgment regarding the appropriate application of one or both of these stress induction tasks. Finally, while our study describes a respectable sample of men and women of comparable age and education, a larger sample size may have increased the ability to detect possible nuanced differences between the tasks or between men and women. Moreover, our sample of women is too small and heterogeneous to examine either the effects of hormonal birth control or menstrual cycle on physiological and psychological responses to these tasks. Sample size is therefore an important consideration for future evaluation of the I-SSST, the TSST, or other social-evaluative stress induction models.

In conclusion, the results of our study replicate and extend previous findings regarding laboratory stress induction and highlight important differences between men and women in some - but not all - measures of acute psychological stress. This further underscores the importance of examining possible sex differences throughout various phases of research, including design, outcome measures, analysis, and interpretation of results. Additionally, we have presented a possible alternative to the TSST for inducing acute psychological stress, which may be useful in some lines of research. While the present study is merely a starting point for determining the potential utility of the I-SSST, our results appear promising for future laboratory examinations of acute psychological stress.

Significance Statement.

This study proposes an alternative laboratory task to induce acute psychological stress: the Iowa Singing Social Stress Test (I-SSST). This task was compared to the “gold standard” Trier Social Stress Test (TSST). Sex differences in cortisol response were observed, with men showing greater cortisol response compared to women. In contrast, our results do not indicate an effect of sex for changes in self-reported stress. Our results suggest that these two tasks do not produce different physiological or subjective stress response patterns, and the I-SSST may be a useful contribution for researchers studying acute stress in the laboratory.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Allison Birnschein, Jocelyn Cole, Delaney Donohue, Marcus Haustein, Jonah Heskje, Nicholas Jones, Kenneth Manzel, and Krystal Wee for their assistance with this study.

This work was supported by a McDonnell Foundation Collaborative Action Award 220020387, the Kiwanis Foundation (D.T.), and National Institutes of Health Predoctoral Training Grant (T32-NS007421 to Dr. Daniel Tranel for trainee KLO). KLO was partially supported by R.J. McElroy Trust.

Authors’ Roles

All authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: AER-H and DT. Acquisition of data: AER-H and ABE. Analysis and interpretation of data: KLO, DT, and AER-H. Drafting of the manuscript: AER-H and KLO. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: KLO. Obtained funding: DT. Administrative, technical, and material support: all authors. Study supervision: DT and AER-H

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

All authors declare that there are no known or potential conflicts of interest, including financial and personal or other relationships, which could inappropriately influence, or be perceived to influence, our work presented here.

References

- Adolphs R. Neural mechanisms for recognizing emotions. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:169–178. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00301-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen AP, Kennedy PJ, Cryan JF, Dinan TG, Clarke G. Biological and psychological markers of stress in humans: Focus on the Trier Social Stress Test. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;38:94–124. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.11.005. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Stress in America: Paying with our health. Washington, DC: Author; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bale TL, Epperson CN. Sex differences and stress across the lifespan. Nature Neuroscience. 2015;18:1413–1420. doi: 10.1038/nn.4112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck RJ, Cesario TC, Yousefi A, Enamoto H. Choral singing, performance perception, and immune system changes in salivary immunoglobulin A and cortisol. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2000;18:87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Birkett MA. The Trier Social Stress Test protocol for inducing psychological stress. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 2011;56:e3238. doi: 10.3791/3238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle NB, Lawton C, Arkbage K, Thorell L, Dye L. Dreading the boards: Stress response to a competitive audition characterized by social-evaluative threat. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2013;26:690–699. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2013.766327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan TW, Tranel D. Stress and emotional memory retrieval: Effects of sex and cortisol response. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;89:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan TW, Tranel D, Kirschbaum C. Hippocampal damage abolishes the cortisol response to psychosocial stress in humans. Horm Behav. 2009;56:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan TW, Driscoll D, Mowrer SM, Sollers JJ, Thayer JF, Kirschbaum C, Tranel D. Medial prefrontal cortex damage affects physiological and psychological stress responses differently in men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: A theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:355–391. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diorio D, Viau V, Meaney MJ. The role of the medial prefrontal cortex (cingulate gyrus) in the regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to stress. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3839–3847. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-09-03839.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt D, Aufegger L, Williamon A. Low-stress and high-stress singing have contrasting effects on glucocorticoid response. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015;6:1242. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrikson M, Gunnarsson R. Psychobiology of stage fright: The effect of public performance on neuroendocrine, cardiovascular and subjective reactions. Biol Psychol. 1992;33:51–61. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(92)90005-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaab J, Rohleder N, Nater UM, Ehlert U. Psychological determinants of the cortisol stress response: The role of anticipatory cognitive appraisal. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:599–610. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillies GE, McArthur S. Estrogen actions in the brain and the basis for differential action in men and women: A case for sex-specific medicines. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:155–198. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.002071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar M, Quevedo K. The neurobiology of stress and development. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DT. The psychology of music performance anxiety. UK: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny D, Driscoll T, Ackermann B. Psychological well-being in professional orchestral musicians in Australia: A descriptive population study. Psychology of Music. 2014;42:210–232. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Kudielka BM, Gaab J, Schommer NC, Hellhammer DH. Impact of gender, menstrual cycle phase, and oral contraceptives on the activity of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. Psychosom Med. 1999;61:154–162. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199903000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Pirke K-M, Hellhammer DH. The 'Trier Social Stress Test' - A tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology. 1993;28:76–81. doi: 10.1159/000119004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudielka BM, Hellhammer DH, Kirschbaum C. Ten years of research with the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST)—Revisited. In: Harmon-Jones E, Winkielman P, editors. Social neuroscience: Integrating biological and psychological explanations of social behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 56–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kudielka BM, Kirschbaum C. Sex differences in HPA axis responses to stress: A review. Biol Psychol. 2005;69:113–132. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudielka BM, von Känel R, Preckel D, Zgraggen L, Mischler K, Fischer JE. Exhaustion is associated with reduced habituation of free cortisol responses to repeated acute psychosocial stress. Biol Psychol. 2006;72:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Miller R, Plessow F, Kirschbaum C, Stalder T. Classification criteria for distinguishing cortisol responders from nonresponders to psychosocial stress: Evaluation of salivary cortisol pulse detection in panel designs. Psychosom Med. 2013;75:832–840. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupien SJ, Fiocco A, Wan N, Maheu F, Lord C, Schramek T, Tu MT. Stress hormones and human memory function across the lifespan. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:225–242. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson DR, Cody MW, Beck JG. Anxiety in musicians: On and off stage. Psychology of Music. 2015;43:438–449. [Google Scholar]

- Oldehinkel AJ, Bouma EMC. Sensitivity to the depressogenic effect of stress and HPA-axis reactivity in adolescence: A review of gender differences. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:1757–1770. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdomo-Guevara E. Is music performance anxiety just an individual problem? Exploring the impact of musical environments on performers’ approaches to performance and emotions. Psychomusicology: Music, Mind, & Brain. 2014;24:66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Pilger A, Haslacher H, Ponocny-Seliger E, Perkmann T, Bohm K, Budinsky A, Winker R. Affective and inflammatory responses among orchestra musicians in performance situation. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;37:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruessner JC, Kirschbaum C, Meinlschmid G, Hellhammer DH. Two formulas for computation of the area under the curve represent measures of total hormone concentration versus time-dependent change. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28:916–931. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sârbescu P, Dorgo M. Frightened by the stage or by the public? Exploring the multidimensionality of music performance anxiety. Psychology of Music. 2014;42:568–579. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer KR, Brosch T. Culture-specific appraisal biases contribute to emotion dispositions. European Journal of Personality. 2009;23:265–288. [Google Scholar]

- Schommer NC, Hellhammer DH, Kirschbaum C. Dissociation between reactivity of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary system to repeated psychosocial stress. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:450–460. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000035721.12441.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selye H. The evolution of the stress concept. American Scientist. 1973;61:692–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi SN, Friedman AR, Kaufer D, Sakhai SA. Glucocorticoids and the brain: Neural mechanisms regulating the stress response. In: Wang JC, Harris C, editors. Glucocorticoid signaling: Advances in experimental medicine and biology. New York: Springer; 2015. pp. 235–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoens VL, Puttonen S, Tervaniemi M. Are music performance anxiety and performance boost perceived as extremes of the same continuum? Psychology of Music. 2015;43:171–187. [Google Scholar]

- Southwick SM, Vythilingam M, Charney DS. The psychobiology of depression and resilience to stress: Implications for prevention and treatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:255–291. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamres LK, Janicki D, Helgeson VS. Sex differences in coping behavior: A meta-analytic review and an examination of relative coping. Personality & Social Psychology Review. 2002;6:2–30. [Google Scholar]

- Vitetta L, Anton B, Cortizo F, Sali A. Mind-body medicine: Stress and its impact on overall health and longevity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1057:492–505. doi: 10.1196/annals.1322.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz PH, Ehlert U, Emini L, Rüdisüli K, Groessbauer S, Gaab J, von Känel R. Anticipatory cognitive stress appraisal and the acute procoagulant stress response in men. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:851–858. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000245866.03456.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf OT. Stress and memory in humans: Twelve years of progress? Brain Res. 2009;1293:142–154. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshie M, Kudo K, Ohtsuki T. Motor/autonomic stress responses in a competitive piano performance. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;11691:368–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]