Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: endoscopic biliary stenting, endoscopic nasobiliary drainage, malignant biliary obstruction, preoperative biliary drainage

Abstract

Background:

Preoperative biliary drainage (PBD) has been widely used to treat patients with malignant biliary obstruction. However, it is still unclear which method of PBD (endoscopic nasobiliary drainage or endoscopic biliary stenting) is more effective. Thus, we carried out a meta-analysis to compare the safety and efficacy of endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) and endoscopic biliary stenting (EBS) in malignant biliary obstruction in terms of preoperative and postoperative complications.

Methods:

We conducted a literature search of EMBASE databases, PubMed, and the Cochrane Library to identify relevant available articles that were published in English, and we then compared ENBD and EBS in malignant biliary obstruction patients. The preoperative cholangitis rate, the preoperative pancreatitis rate, the incidence of stent dysfunction, the postoperative pancreatic fistula rate, and morbidity were analyzed. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to express the pooled effect on dichotomous variables, and the pooled analyses were performed using RevMan 5.3.

Results:

Seven published studies (n = 925 patients) were included in this meta-analysis. We determined that patients with malignant biliary obstruction who received ENBD had reductions in the preoperative cholangitis rate (OR = 0.35, 95% CI = 0.25–0.51, P < 0.0001), the postoperative pancreatic fistula rate (OR = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.18–0.82, P = 0.01), the incidence of stent dysfunction (OR = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.28–0.56, P < 0.0001), and morbidity (OR = 0.47, 95% CI = 0.27–0.82, P = 0.008) compared with patients who received EBS.

Conclusions:

The current meta-analysis suggests that ENBD is better than EBS for malignant biliary obstruction in terms of the preoperative cholangitis rate, the postoperative pancreatic fistula rate, the incidence of stent dysfunction, and morbidity. However, a limitation is that there are no data from randomized controlled trials.

1. Introduction

Malignant biliary obstruction (MBO) is invariably attributable to carcinoma of Vater's ampulla, pancreatic carcinoma, hilar cholangiocarcinoma (HCA), and metastatic disease, and the only curative treatment for MBO is surgical resection. The highest incidence of MBO is in Asia, and it is associated with a poor prognosis for patients, whose median survival is only 1 to 4 years after surgery.[1] Regardless of whether a patient receives a pancreaticoduodenectomy or HCA surgery, which has been deemed the standard of care, MBO is associated with significant mortality and morbidity. Moreover, obstructive jaundice resulting from MBO may lead to coagulopathy, liver function decline, and pre- or postoperative cholangitis.[2] As the severity of the disease increases, there are more complications, such as renal dysfunction, hepatic failure, and other adverse outcomes.[3]

Preoperative biliary drainage, which added a new dimension to the management of MBO, has been widely used on a variety of patients in many clinical centers to resolve jaundice, improve clinical outcomes, and decrease postoperative complications.[4] Several studies have indicated that biliary drainage is associated with improvements in the postoperative mortality, morbidity, and resection rate of patients.[5] There are three types of PBD—endoscopic nasobiliary drainage, endoscopic biliary stenting, and percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage (PTCD).

PTCD is not recommended as the initial method of PBD due to the risk of tumor seeding and other adverse events, in addition to the discomfort of patients receiving such invasive treatment.[6] It is still unclear whether ENBD or EBS is more effective and safe for use in MBO patients. Thus, we carried out a meta-analysis to compare the safety and efficacy of ENBD and EBS in MBO treatment in terms of pre- and postoperative complications.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

We conducted a literature search of the EMBASE, PubMed, and Cochrane Library databases to identify relevant available articles published in English between database inception and May 2016. The search terms included “nasobiliary drainage,” “nasobiliary catheter,” “nasobiliary drain,” and “ENBD” combined with the terms “internal endoscopic biliary drainage,” “internal EBD,” “endoscopic biliary stenting,” “EBS,” “endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage,” “ERBD,” “stent,” and “stenting.” We also reviewed the reference lists of the included studies for undetected relevant studies. We contacted the original authors to obtain extra information if necessary.

2.2. Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: original research from observational studies or randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in adults; the interventions of interest were ENBD and EBS; the participants of interest were patients suffering from MBO before surgery; an odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for the risk of pre- and postoperative complications from PBD was provided or could be calculated; and the most recent and complete study was included if the data from the same population had been published more than once.

Two investigators searched and reviewed all identified studies independently. If the 2 investigators could not reach a consensus about the eligibility of an article, it was resolved by consulting with a third reviewer.

2.3. Data extraction and quality assessment

The following data were independently extracted from each study by 2 investigators: the first author's name, the publication year, the country where the study was performed, the study design, the size of the drainage tube, the age range or mean age at baseline, the number of participants and deaths, pre- and postoperative complications, and stent or drainage dysfunction.

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, an instrument for evaluating the quality of observational studies, was used to assess each of the included studies based on population selection, study comparability and outcome of the report.[7] Except for 1 conference abstract that provided the necessary data, each study was awarded a score of 1 point to 9 points.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis was conducted using RevMan software version 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). ORs with a 95% CI were calculated to compare the incidence of pre- and postoperative complications between the ENBD group and the EBS group. Heterogeneity among the included studies was qualitatively evaluated using a χ2-based Q test. P values less than 0.05 showed that there was statistically significant heterogeneity across the studies. The level of heterogeneity between studies was evaluated using I2 statistics. I2 <30% was considered to be low heterogeneity, and a fixed-effects model was applied; 30% ≤ I2 ≤ 50% was considered to be moderate heterogeneity; and I2 > 50% represented high heterogeneity. A random-effects model was applied when I2 ≥ 30%. Sensitivity analysis was performed by removing 1 study at a time to assess whether the results could have been markedly affected by a single study. The publication bias was assessed using funnel plots.

3. Results

3.1. Search results and study characteristics

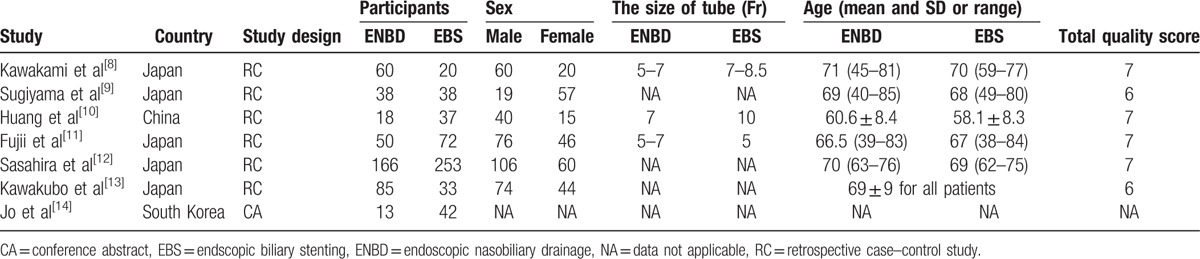

A total of 612 articles were retrieved by searching electronic databases and manually searching relevant reference lists. After duplicates were identified and excluded, 527 articles remained. We then excluded unrelated reviews, case reports, systematic reviews and meta-analyses, as well as studies that were clearly irrelevant based on their title or abstract; 50 articles remained. Of these, 7 articles[8–14] (6 case–control studies and 1 conference abstract) were used in this meta-analysis. The detailed steps of our literature search are shown in Fig. 1. Seven studies with a total of 925 patients were included in the final analysis. The sample sizes of all included studies ranged from 55 to 419. In total, 430 patients (46%) received ENBD, and 495 patients received EBS. Five studies came from Japan, 1 came from China, and 1 came from South Korea. The characteristics of these studies are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for the study selection.

Table 1.

The baseline characteristics and the quality of the enrolled studies.

3.2. Incidence of preoperative cholangitis

Data from the 7[8–14] articles including 430 cases in the ENBD group and 495 cases in the EBS group were used in this meta-analysis. Three studies[8–9,11] reported that ENBD decreased the incidence of preoperative cholangitis before standard resection or palliative surgery compared with EBS, while no significant association was reported in 4 studies.[10,12–14] Moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 31%, P = 0.19) was found, so we chose a random-effect model to pool the OR. Overall, the pooled data demonstrated that ENBD was associated with a low incidence of preoperative cholangitis (OR = 0.35, 95% CI = 0.25–0.51, P < 0.0001) in the MBO patients (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plots of preoperative cholangitis rates. Squares indicate study-specific odds ratios (the size of the square reflects the study-specific statistical weight); horizontal lines indicate 95% CIs; and the diamond indicates the summary relative risk estimate with its 95% CI. CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio.

3.3. Incidence of preoperative pancreatitis

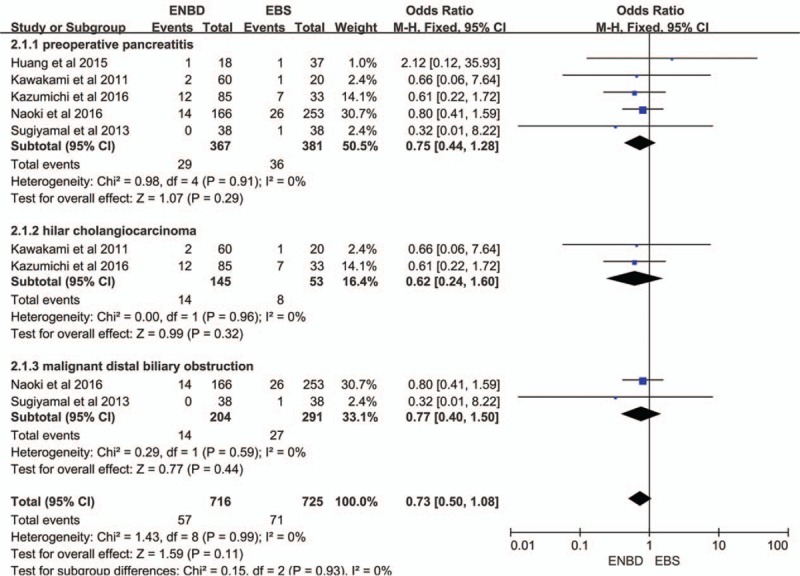

Data from 5 articles,[8–10,12–13] including 367 cases in the ENBD group and 381 cases in the EBS group, were used in this meta-analysis. All 5 studies reported that there was no significant difference in the incidence of preoperative pancreatitis between the ENBD and EBS groups. No heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.91) was found, so we chose a fixed-effect model to pool the OR. Overall, the pooled data demonstrated that neither ENBD nor EBS was associated with a significantly lower incidence of preoperative pancreatitis (OR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.44–1.28, P = 0.29) in MBO patients (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plots of preoperative pancreatitis. Squares indicate study-specific odds ratios (the size of the square reflects the study-specific statistical weight); horizontal lines indicate 95% CIs; and the diamond indicates the summary relative risk estimate with its 95% CI. CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio.

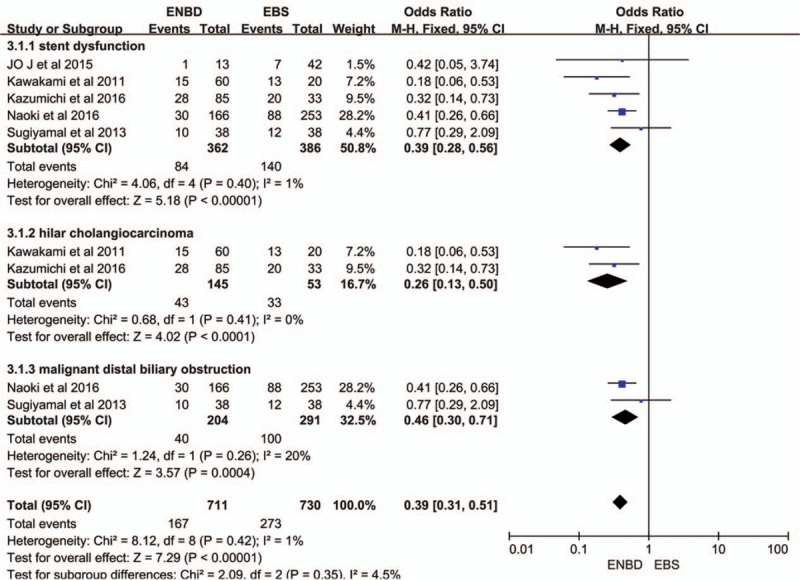

3.4. Stent dysfunction rate

Five of the 7 studies,[8,9,12–14] including 362 cases in the ENBD group and 386 cases in the EBS group, reported a stent dysfunction rate. Three studies[8,12,13] reported that ENBD reduced the incidence of preoperative stent dysfunction compared with EBS, but the results from 2 studies,[9,14] showed little statistical difference. Low heterogeneity (I2 = 1%, P = 0.40) was found, so we chose a fixed-effect model to pool the OR. Overall, the pooled data demonstrated that ENBD was associated with a low incidence of stent dysfunction (OR = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.28–0.56, P < 0.0001) in MBO patients (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plots of stent dysfunction rates. Squares indicate study-specific odds ratios (the size of the square reflects the study-specific statistical weight); horizontal lines indicate 95% CIs; and the diamond indicates the summary relative risk estimate with its 95% CI. CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio.

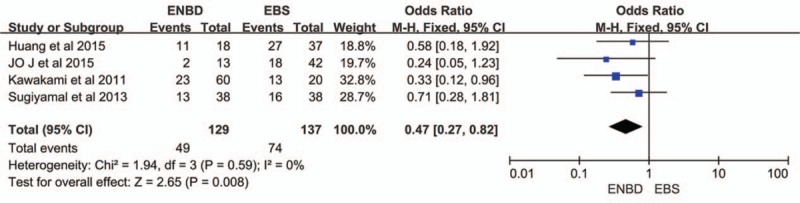

3.5. Morbidity

Four studies was used to assess morbidity,[8–10,14] which was defined as the incidence of all pre and postoperative complications. Although 3 studies[9,10,14] showed that ENBD had no significant advantage in terms of morbidity compared with EBS, the pooled results had no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.59) and showed that ENBD had a significantly lower incidence of morbidity than EBS (OR = 0.47, 95% CI = 0.27–0.82, P = 0.008) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Forest plots of morbidity. Squares indicate study-specific odds ratios (the size of the square reflects the study-specific statistical weight); horizontal lines indicate 95% CIs; and the diamond indicates the summary relative risk estimate with its 95% CI. CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio.

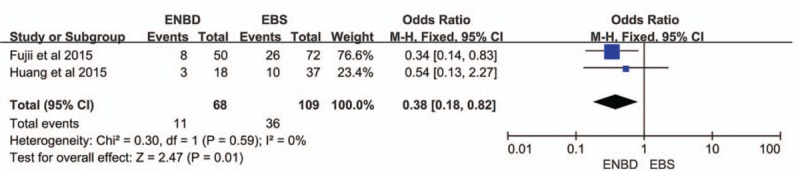

3.6. Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula (POPF)

The meta-analysis was used to assess the effect of POPF in 2 trials.[10,11] The pancreatic fistula rate was significantly lower in the ENBD group than in the EBS group (OR = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.18–0.82, P = 0.01) based on the pooled data, which showed no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.59) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Forest plots of postoperative pancreatic fistula. Squares indicate study-specific odds ratios (the size of the square reflects the study-specific statistical weight); horizontal lines indicate 95% CIs; and the diamond indicates the summary relative risk estimate with its 95% CI. CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio.

3.7. Subgroup analysis, sensitivity analysis, and assessment of risk of bias

Subgroup analysis showed a higher incidence of preoperative cholangitis in the EBS group than in the ENBD group among HCA patients (OR = 0.40, 95% CI = 0.21–0.75, P = 0.005) and malignant distal biliary obstruction patients (OR = 0.34, 95% CI = 0.26–0.44, P < 0.00001) (Fig. 2). The stent dysfunction rate was also higher in the EBS group than in the ENBD group among HCA patients (OR = 0.26, 95% CI = 0.13–0.50, P < 0.0001) and malignant distal biliary obstruction patients (OR = 0.46, 95% CI = 0.30–0.71, P = 0.0004) (Fig. 4). There was no significant difference in the preoperative pancreatitis rate between ENBD and EBS in HCA patients (OR = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.24–1.60, P = 0.32) or malignant distal biliary obstruction patients (OR = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.40–1.50, P = 0.44) (Fig. 3). Sensitivity analysis suggested that the data in this meta-analysis were relatively stable. Funnel plots for the preoperative cholangitis rate, the preoperative pancreatitis rate, the incidence of stent dysfunction, and morbidity were drawn (see Figures, Supplemental Content 1–4, which illustrate funnel plots for preoperative cholangitis rate, preoperative pancreatitis rate, incidence of stent dysfunction, and morbidity). The publication bias was small because the points on the funnel plots were substantially symmetric. A funnel plot for POPF was not made due to the small number of studies.

4. Discussion

The management of biliary cancer and pancreatic head cancer is becoming increasingly diversified and effective due to the increased success rate of surgical resection, advances in interventional radiology therapy, and the use of chemotherapy for inoperable cancers.[15–17] Nevertheless, the feasibility of surgery or other treatments depends not only on the TNM staging or the size of the tumor but also on the jaundice that arises from biliary obstruction, basic characteristic of patients, and other concomitant disease. If bile duct obstruction cannot be relieved, many patients may not be able to receive further treatment.[13] To further improve the therapeutic efficacy for treating MBO, the primary concern for surgeons has been how to achieve the most drainage.

Endoscopic biliary drainage (EBD), which is beneficial due to its advantages in cosmetic appeal[18] and noninvasiveness, is generally believed to be more appropriate than PTCD. Although for decades there has been no clear consensus about the safety and efficacy of EBD in MBO, EBD has been widely used in patients who are unable to undergo elective surgery immediately after a diagnosis of cancer due to obstructive jaundice or other reasons. There are 2 types of EBD (ENBD and EBS), and no systematic examination has been performed to determine which is more appropriate for treating MBO. The present meta-analysis was performed to assess the safety and efficacy of ENBD and EBS.

ENBD is an external procedure that drains out the bile and decompresses the biliary obstruction, which is convenient for bile cytology[19] and cholangiography, whereas EBS makes diagnosis via the output of bile more difficult. Although discomfort in the throat would prevent ENBD from being an initial drainage method, the major advantage of ENBD is the lower incidence of preoperative cholangitis and other complications. A previous meta-analysis and other RCTs,[20–23] which enrolled both benign and MBO participants, reported no significant difference between ENBD and EBS in terms of preoperative cholangitis and other complications, whereas the present meta-analysis demonstrated that ENBD was associated with a lower preoperative cholangitis rate (OR = 0.35, 95% CI = 0.25–0.51, P < 0.0001) and morbidity (OR = 0.47, 95% CI = 0.27–0.82, P = 0.008), which was supported by other studies.[24–26] The stents used for EBS, which connect the biliary tract and the duodenum, could become clogged due to intestinal microbes and reverse the flow of food when used for distal malignant obstruction. This is not only one of the reasons why biliary tract infections and preoperative cholangitis occur but also a potential risk of postoperative infectious complications.[11] Meta-analysis showed that stent dysfunction occurred more often in the EBS group (OR = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.28–0.56, P < 0.0001) than in the ENBD group, as well as the causes of dysfunction were stent occlusion in EBS and dislocation in ENBD.[8] Therefore, it is not surprising that ENBD is associated with a lower rate of preoperative cholangitis and other infectious complications.

As an internal biliary drainage method, EBS has advantages for hepatic function and immune function by preserving enterohepatic circulation, thereby maintaining metabolism and vitamin absorption.[12,13] Another advantage of EBS is the absence of discomfort in the pharynx and nasal cavities compared with ENBD. Son et al[27] reported that a short-duration treatment was more appropriate in patients with periampullary cancer and was associated with fewer preoperative complications. The time needed for EBS was always longer than that needed for other PBD methods, which lead to prolonged hospital stays and an increased probability of infection.[10] In addition, meta-analysis revealed that the pancreatic fistula rate was significantly higher in the EBS group than in the ENBD group (OR = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.18–0.82, P = 0.01). Fujii et al[11] found that EBS was an independent predictive factor of pancreatic fistula, and POPF was found to be a reason for abdominal and surgical site infections.[28,29] Although this observation may result from the biases of pooling small-sample studies, it would affect the choice of surgeon.

Furthermore, the incidence of preoperative pancreatitis was higher in the EBS group than in the ENBD group even though the present meta-analysis and other studies showed no significant difference.[8,9,12,13] In a high-volume prospective study, Wilcox et al[30] showed that EBS was one of the factors associated with pancreatitis. The placement of stents, especially large-bore stents, would lead to the obstruction of the adjacent pancreatic orifice and restrict the outflow of the pancreatic juice, which could be a potential risk for pancreatitis. In addition, an endoscopic sphincterotomy is routinely performed when placing large-bore plastic stents or self-expandable metal stents. Perforations, ulcers, and stent dysfunction due to endoscopic sphincterotomy are always associated with pancreatitis and other complications.[31] Nevertheless, the question of whether endoscopic sphincterotomies could lead to a higher incidence of pancreatitis is still debated when this procedure is also used in ENBD.

There were several limitations of this meta-analysis that should be taken into consideration when interpreting our results. First, we did not assess the impact of different types or stents and whether the procedure of endoscopic sphincterotomy was used in the procedure of drainage. Second, the number of included studies and the subgroup analysis were insufficient, and the study design was retrospective and lacked randomized controls. Third, because of limited information, the participants were all from Asia. Fourthly, self-expandable metal stents, which were not used in our enrolled studies, are reported to be associated with fewer complications and lower occlusion rates than plastic stents.[32–34] Finally, there could be a publication bias, which may influence the authenticity of our results.

5. Conclusions

Patients with MBO who are treated with ENBD have lower rates of preoperative cholangitis, postoperative pancreatic fistula, stent dysfunction, and morbidity than patients who are treated with EBS. The current meta-analysis suggests that ENBD is better than EBS for treating patients with MBO in terms of the preoperative cholangitis rate, the postoperative pancreatic fistula rate, the incidence of stent dysfunction, and morbidity. However, the method of biliary drainage in MBO is variable and depends upon various factors, such as the patient's clinical status and comfort, disease status, and the availability of technology and expertise, which should be taken into full consideration when interpreting our results. In addition, we still need further multicenter RCTs to prove our observations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors thank all the anonymous reviewers and editors for their helpful suggestions to improve the quality of our paper.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CI = confidence intervals, EBD = endoscopic biliary drainage, EBS = endoscopic biliary stenting, ENBD = endoscopic nasobiliary drainage, HCA = hilar cholangiocarcinoma, MBO = malignant biliary obstruction, PBD = preoperative biliary drainage, POPF = postoperative pancreatic fistula, PTCD = percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage, RCTs = randomized controlled trials, OR = odds ratio.

Ethical approval was not necessary, as this study is a “Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.”

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

References

- 1.Rerknimitr R, Kladcharoen N, Mahachai V, Kullavanijaya P. Result of endoscopic biliary drainage in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol 2004; 38:518–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song TJ, Lee JH, Lee SS, et al. Metal versus plastic stents for drainage of malignant biliary obstruction before primary surgical resection. Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 84:814–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myatra S, Divatia JV, Jibhkate B, et al. Preoperative assessment and optimization in periampullary and pancreatic cancer. Indian J Cancer 2011; 48:86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kloek JJ, van der Gaag NA, Aziz Y, et al. Endoscopic and percutaneous preoperative biliary drainage in patients with suspected hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg 2010; 14:119–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coates JM, Beal SH, Russo JE, et al. Negligible effect of selective preoperative biliary drainage on perioperative resuscitation, morbidity, and mortality in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Arch Surg (Chicago, Ill: 1960) 2009; 144:841–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi SH, Gwon DI, Ko GY, et al. Hepatic arterial injuries in 3110 patients following percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. Radiology 2011; 261:969–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin B, Paesmans M, Berghmans T, et al. Role of Bcl-2 as a prognostic factor for survival in lung cancer: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 2003; 89:55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawakami H, Kuwatani M, Onodera M, et al. Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage is the most suitable preoperative biliary drainage method in the management of patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol 2011; 46:242–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugiyama H, Tsuyuguchi T, Sakai Y, et al. Preoperative drainage for distal biliary obstruction: endoscopic stenting or nasobiliary drainage? Hepato-gastroenterology 2013; 60:231–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang X, Liang B, Zhao XQ, et al. The effects of different preoperative biliary drainage methods on complications following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Medicine (United States) 2015; 94:e723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujii T, Yamada S, Suenaga M, et al. Preoperative internal biliary drainage increases the risk of bile juice infection and pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy a prospective observational study. Pancreas 2015; 44:465–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sasahira N, Hamada T, Togawa O, et al. Multicenter study of endoscopic preoperative biliary drainage for malignant distal biliary obstruction. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22:3793–3802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawakubo K, Kawakami H, Kuwatani M, et al. Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage has lower incidence of complications than endoscopic biliary stenting for the management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol (Australia) 2015; 30:235. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jo JH, Chung MJ, Park JY, et al. Preoperative biliary drainage in klatskin tumor. Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 81:AB363. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dinant S, Gerhards MF, Rauws EA, et al. Improved outcome of resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma (Klatskin tumor). Ann Surg Oncol 2006; 13:872–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakeeb A, Tran KQ, Black MJ, et al. Improved survival in resected biliary malignancies. Surgery 2002; 132:555–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seyama Y, Makuuchi M. Current surgical treatment for bile duct cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13:1505–1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim KM, Park JW, Lee JK, et al. A comparison of preoperative biliary drainage methods for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: endoscopic versus percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. Gut Liver 2015; 9:791–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yagioka H, Hirano K, Isayama H, et al. Clinical significance of bile cytology via an endoscopic nasobiliary drainage tube for pathological diagnosis of malignant biliary strictures. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2011; 18:211–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang RL, Cheng L, Cai XB, et al. Comparison of the safety and effectiveness of endoscopic biliary decompression by nasobiliary catheter and plastic stent placement in acute obstructive cholangitis. Swiss Med Wkly 2013; 143:w13823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma BC, Kumar R, Agarwal N, Sarin SK. Endoscopic biliary drainage by nasobiliary drain or by stent placement in patients with acute cholangitis. Endoscopy 2005; 37:439–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee DW, Chan AC, Lam YH, et al. Biliary decompression by nasobiliary catheter or biliary stent in acute suppurative cholangitis: a prospective randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 56:361–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sawas T, Al Halabi S, Patel M. A comparison between nasobiliary drainage and biliary stenting in acute suppurative cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109:S79–S80. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mezhir JJ, Brennan MF, Baser R, et al. A matched case-control study of preoperative biliary drainage (PDB) in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma: routine PBD is not justified. Gastroenterology 2009; 136:A916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Velanovich V, Kheibek T, Khan M. Relationship of postoperative complications from preoperative biliary stents after pancreaticoduodenectomy. A new cohort analysis and meta-analysis of modern studies. JOP 2009; 10:24–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawai M, Tani M, Hirono S, et al. Association of preoperative biliary drainage related complications with postoperative complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB 2014; 16:111–112. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Son JH, Kim J, Lee SH, et al. The optimal duration of preoperative biliary drainage for periampullary tumors that cause severe obstructive jaundice. Am J Surg 2013; 206:40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagai S, Fujii T, Kodera Y, et al. Recurrence pattern and prognosis of pancreatic cancer after pancreatic fistula. Ann Surg Oncol 2011; 18:2329–2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanda M, Fujii T, Kodera Y, et al. Nutritional predictors of postoperative outcome in pancreatic cancer. Brit J Surg 2011; 98:268–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilcox CM, Phadnis M, Varadarajulu S. Biliary stent placement is associated with post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 72:546–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Artifon EL, Sakai P, Ishioka S, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy before deployment of covered metal stent is associated with greater complication rate: a prospective randomized control trial. J Clin Gastroenterol 2008; 42:815–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liberato MJ, Canena JM. Endoscopic stenting for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: efficacy of unilateral and bilateral placement of plastic and metal stents in a retrospective review of 480 patients. BMC Gastroenterol 2012; 12:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sangchan A, Kongkasame W, Pugkhem A, et al. Efficacy of metal and plastic stents in unresectable complex hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 76:93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perdue DG, Freeman ML, DiSario JA, et al. Plastic versus self-expanding metallic stents for malignant hilar biliary obstruction: a prospective multicenter observational cohort study. J Clin Gastroenterol 2008; 42:1040–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.