Abstract

Clinical evidence for the effectiveness of hypnosis in the treatment of acute, procedural pain was critically evaluated based on reports from randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs). Results from the 29 RCTs meeting inclusion criteria suggest that hypnosis decreases pain compared to standard care and attention control groups and that it is at least as effective as comparable adjunct psychological or behavioral therapies. In addition, applying hypnosis in multiple sessions prior to the day of the procedure produced the highest percentage of significant results. Hypnosis was most effective in minor surgical procedures. However, interpretations are limited by considerable risk of bias. Further studies using minimally effective control conditions and systematic control of intervention dose and timing are required to strengthen conclusions.

Procedural pain poses a significant and substantial problem. Though it would be impossible to fully quantify the incidence of painful medical procedures, the scope of the problem is estimable, given the $560–$635 billion in yearly pain-related expenditures in the United States (Gay, Philippot, & Luminet, 2002). The challenge of achieving adequate pain control without adverse side effects further compounds the problem and provides rationale for seeking complementary medicine alternatives (Askay, Patterson, Jensen, & Sharar, 2007; Fleming, Rabago, Mundt, & Fleming, 2007).

Hypnosis has a long history in the treatment of pain (Elkins, 2014; Gay et al., 2002; Hilgard & Hilgard, 1994; Liossi & Hatira, 1999; Patterson, 2010; Patterson & Jensen, 2003) and is one of the most recognized nonpharmacological pain management techniques. Despite the long legacy of hypnoanalgesia in medicine, mechanisms of hypnotic pain relief are still debated. One of the two most influential theories proposes dissociational processes and emphasizes the importance of hypnotic susceptibility and an altered state of consciousness (Bowers, 1992; Hilgard & Hilgard, 1994), while the other suggests that social and cognitive processes are responsible for hypnosis induced analgesia and highlights the significance of contextual variables, compliance with instructions, expectancies, cognitive strategies and role enactment (Chaves, 1993).

A number of previous reviews have examined the effectiveness of hypnosis in addressing pain (Accardi & Milling, 2009; Cyna, McAuliffe, & Andrew, 2004; Elkins, Jensen, & Patterson, 2007; Jensen & Patterson, 2005; Montgomery, DuHamel, & Redd, 2000; Patterson & Jensen, 2003; Richardson, Smith, McCall, & Pilkington, 2006); however, the most recent review involving studies with an adult population on procedural pain was conducted over 10 years ago. The aim of this review is to provide an updated overview of the literature incorporating studies conducted since the last comprehensive review on acute, procedural pain for both adults and children in 2003 (Patterson & Jensen, 2003) and to assess how procedural, interventional, and methodological factors can affect pain related outcomes based on the results of the included randomized controlled clinical trials.

Method

The following databases were searched from their inception to November, 2013: MEDLINE, HealthSource: Nursing/Academic Edition, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, PsycCRITIQUES and the Psychological and Behavioral Sciences. Search terms used were (hypnosis AND pain AND procedure); (hypnotherapy AND pain AND procedure); (hypnosis AND pain AND surgery); (hypnotherapy AND pain AND surgery); (hypnosis AND pain AND operation); and (hypnotherapy AND pain AND operation).

Prospective, randomized, controlled trials of hypnosis for acute, procedural pain were included. Studies were not excluded based upon specifics of the hypnosis or control interventions. However, studies were excluded if they were case studies or case series, if they were not clinical trials, if they were not randomized or controlled, or if hypnosis was poorly defined or was combined with several other treatments as a part of a larger, complex intervention (in which the effects of hypnosis intervention would be difficult to identify). Studies were also considered irrelevant if they were not specifically examining the use of hypnosis for the treatment of procedural pain. For example, studies of hypnoanalgesia in labor were excluded because labor pain cannot be characterized as pain caused by a medical procedure. Language restrictions were not applied. However, our search resulted only in English language studies.

All trials meeting the aforementioned criteria were reviewed in full by two independent reviewers. The reviewers extracted procedure type, study design, whether intention to treat analysis (ITT) was used, intervention and control regimens (with special attention to timing and dose of the intervention), sample size by groups, pain related measures used, results on each measure, methodological quality indicators (randomization, blinding, dropouts), whether hypnotizability was assessed, used for participant inclusion, or found to be correlated with any of the outcomes, and the conclusion of the authors on the effectiveness of hypnosis for acute pain relief. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers, ZK and CK, and, if necessary, by seeking guidance from the third reviewer, GE, who also reviewed all ratings of the first two reviewers.

Methodological quality was evaluated by way of a modification of the Oxford, 5-point Jadad score (Jadad et al., 1996). In order to account for the difficulty in blinding of hypnosis practitioners, a maximum of 4 points were awarded in the following manner: 1 point for a study description that indicated the study was randomized; 1 point for use of an appropriate randomization technique as well as a 1 point penalty deduction for inappropriate randomization technique; 1 point for providing explanation of withdrawals and dropouts; and 1 point if the experimental and hospital staff were blinded to treatment assignment.

The effectiveness of hypnosis for controlling acute pain has been examined in a large variety of medical procedures in both adult and pediatric populations. We have to acknowledge that there are great differences in the type, location and level of pain experienced in these procedures; thus, direct pooling or comparison of effect sizes could be misleading. To overcome this problem, results were simplified to either being significant or non-significant by measures used. In the assessment of the effects of moderating factors, we used the measurements as basic units instead of studies to control for the inflated alpha error probability originating from multiple testing of the same hypothesis. Thus, the indicator of effectiveness in a given moderator condition (like interventions consisting of one hypnosis session instead of many) was the percentage of the number of measurements with significant effects within the total number of measurements in the study pool. In this assessment of moderators, only comparisons of hypnosis vs. attention control, or, if not applicable, hypnosis vs. usual care were entered.

Results

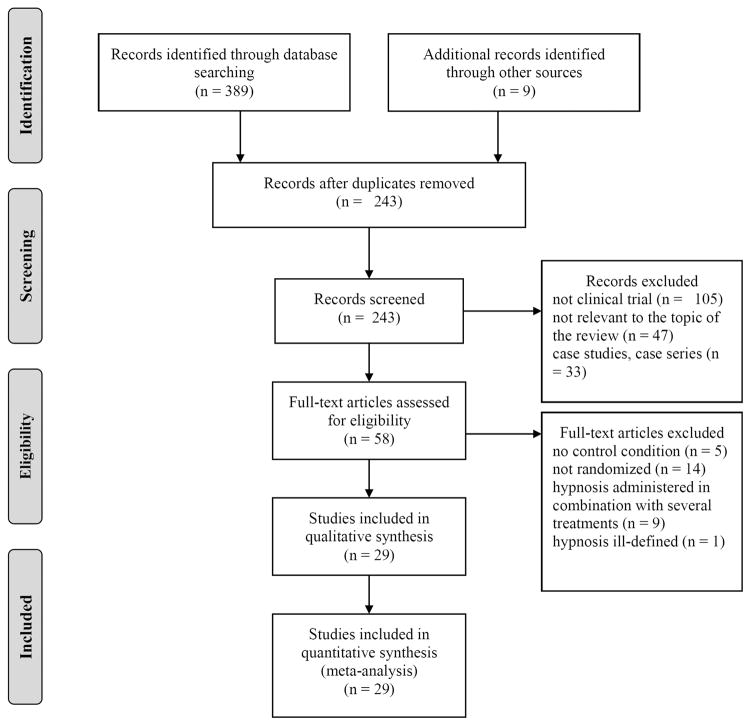

The initial searches yielded a total of 398 articles. Of these, 155 were duplicates, and of the remaining 243 articles, 29 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) met the aforementioned criteria for inclusion in the review (Enqvist & Fischer, 1997; Everett, Patterson, Burns, Montgomery, & Heimbach, 1993; Faymonville et al., 1997; Harandi, Esfandani, & Shakibaei, 2004; Katz, Kellerman, & Ellenberg, 1987; Kuttner, Bowman, & Teasdale, 1988; Lambert, 1996; Lang et al., 2000; Lang et al., 2006; Lang, Joyce, Spiegel, Hamilton, & Lee, 1996; Liossi & Hatira, 1999, 2003; Liossi, White, & Hatira, 2006, 2009; Mackey, 2009; Marc et al., 2008; Marc et al., 2007; Massarini et al., 2005; Montgomery et al., 2007; Montgomery, Weltz, Seltz, & Bovbjerg, 2002; Patterson, Everett, Burns, & Marvin, 1992; Patterson & Ptacek, 1997; Smith, Barabasz, & Barabasz, 1996; Snow et al., 2012; Syrjala, Cummings, & Donaldson, 1992; Wall & Womack, 1989; Weinstein & Au, 1991; Wright & Drummond, 2000; Zeltzer & LeBaron, 1982). The PRISMA Flow Diagram in Figure 1 provides details on the inclusion and exclusion process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

The methodological quality of studies varied, (Jadad score range 0–4, M = 2.33). Nine RCTs provided descriptions for randomization methods, and 11 trials provided adequate detail of dropouts and withdrawals. One study used a crossover design; all other studies applied a parallel design. Key data are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key Data Controlled Trials of Hypnosis for Acute and Procedural Pain

| First Author, Year | Study Design Quality Score Intention-to-Treat Analysis | Condition Sample Size (Randomized/Analyzed) | Intervention (regimen) | Control (regimen) | Pain Measurement Methods | Main Result | Authors’ Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zeltner, 1982 | Parallel design 1 Not reported |

Bone marrow aspirations or lumbar puncture 33/33 |

Patients were helped to become increasingly involved in interesting and pleasant images. (n = 16) | Distraction. This involved asking the child to focus on objects in the room rather than on fantasy. (n = 17) | 1) pain self-report and observer rating aggregated (1–5) 2) anxiety self-report and observer rating aggregated (1–5) * Both measures collected at baseline and 1–3 BMAs post-baseline |

1) Pain self-ratings decreased in both groups significantly, but hypnosis was significantly better in pain reduction for bone marrow aspiration (p < .03) and lumbar puncture (p<.02). 2) Anxiety was also significantly more reduced by hypnosis for bone marrow aspiration (p < .05). |

‘(…) hypnosis was shown to be more effective than non-hypnotic techniques for reducing procedural distress in children and adolescents with cancer.’ |

| Katz, 1987 | Parallel design 2 Not reported |

Bone marrow aspirations or lumbar puncture (in some cases) 36/36 |

Training in hypnosis and self-hypnosis (two, 30 min. interventions prior to each BMA + 20 min session preceding each of three BMAs. (n= 17) | Play matched for time and attention to hypnosis group (n=19) | 1) Pain self-report (0–100 scale) patterned after thermometer. 2) PBRS during procedure * Both measures collected at baseline and 3 BMAs post-baseline |

1) Pain self-report scores decreased significantly from baseline at each subsequent BMA in both groups (p<.05). There were no significant intergroup differences in self-reported pain. 2) No significant intergroup differences in observational ratings. |

‘It appears that hypnosis and play are equally effective in reducing subjective pain for BMAs. |

| Kuttner, 1988 | Parallel design 2 Not reported |

Bone marrow aspiration 48/48 |

5–20 minute preparation just before procedure and hypnosis and guided imagery facilitating the involvement in an interesting story during procedure. Additionally participants could turn pain off with a ‘pain switch’. (n = 16) | 1) standard care (n = 16) 2) 5–20 minute preparation and training in breathing technique, and distraction with toys during procedure. (n = 16) |

1) PBRS during procedure by 2 observers 2) observed anxiety rating scale (1–5), 3) observed pain rating scale (1–5) 2) and 3) were the aggregated score of physician, nurse, parent, 2 observers 4) anxiety self-report (pictorial scale) 5) pain self-report (pictorial scale) |

1) no difference in the whole sample, but younger patients had a lower PBRS in the hypnosis group than both other groups (ps < .05). 2) observed anxiety was lower for older children in the hypnosis group and the distraction group compared to the control (p<.05), but not hypnosis vs. distraction. While hypnosis was better at anxiety reduction than distraction for younger patients (p<.05),. 3) no difference in the whole sample, observed pain was lower in in older patients in the hypnosis group compared to the standard care group.(p<.05). While for younger patients, hypnosis was better for pain reduction.(p<.05). 4) no effect on anxiety self-report 5) no effect on pain self-report |

‘(…) distress of younger children, 3–6 years old was best alleviated by hypnotic therapy, imaginative involvement, whereas older children’s observed pain and anxiety was reduced by both distraction and imaginative involvement techniques.’ |

| Wall, 1989 | Parallel design 3 Not reported |

Bone marrow aspirations or lumbar puncture 20/201 |

Hypnosis (two group training sessions during the week prior to the procedure, n= 11) | Active cognitive strategy (two group training sessions during the week prior to the procedure, n= 9) | 1) 10cm VAS2 (procedural pain, behavioral observation and self-reports, three times) 2) MPQ3 (affective and procedural components of pain, one time, subjects above 12yo) 3) independent observer blind to treatment assignment – rated procedural pain via 10 cm VAS |

1) Self-reported pain decreased in both groups (p = .003) with no significant between group differences. 2) MPQ present pain index (p<.02) and pain ratings index (p<.01) significantly decreased in both groups with no significant between group differences. 3) Observational pain ratings reflected decrease in procedural pain (p<.009). Between group differences were insignificant. |

‘(…) both strategies were effective in providing pain reduction.’ |

| Weinstein, 1991 | Parallel design 0 Not reported |

Angioplasty (by inflating balloons in occluded coronary arteries) 32/32 |

Hypnosis (30 min) before the day of the procedure, with posthypnotic suggestions for relaxation during angioplasty. (n = 16) | Standard care (n = 16) | 1) Pulse 2) Blood pressure 3) Pain medication used 4) balloon inflation time |

1) No difference in pulse 2) No difference in blood pressure 3) Fewer patients needed additional pain medication in the hypnosis group (p = .05) 4) Balloon could remain inflated 25% longer in the hypnosis group (not significant, p = .10) |

‘(…) reduction [of analgesic use] was significant, and in line with reports of less pain medication required by burn victims who have mad hypnotic therapy’ |

| Patterson, 1992 | Parallel design 3 Not reported |

33/30 | Hypnosis (25 min) prior to debridement + standard care | 1) Standard care 2) Attention and information control + standard care |

1) 10 cm VAS self-report 2) 10 cm nurse administered VAS 3) pain medication stability |

1a) significant within group difference in hypnosis group (p=.0001) not seen in controls. 1b) Hypnosis participants had significantly less post-treatment pain than attention (p=.03) and standard care control (p=.01). 2a) significant within group pre-post reduction in pain among hypnosis participants not seen in controls. 2b) no significant intergroup differences 3) no significant intergroup differences |

‘Hypnosis is a viable adjunct treatment for burn pain.’ |

| Syrjala, 1992 | Parallel design 2 Not reported |

Bone marrow aspiration 67/45 |

1) Hypnosis (2 pre-transplant sessions +10 booster sessions)+ standard medical care 2) Cognitive behavioral coping skills training (2 pre-transplant sessions +10 booster sessions) + standard medical care |

1) Therapist contact control (2 pre-transplant sessions+10 booster sessions)+ standard medical care 2) Treatment as usual (standard medical care |

1) VAS self-report of oral pain 2) opioid medication use |

1) Hypnosis participants experienced less pain than therapist contact or CBT participants (p= .033). 2) no significant differences between groups |

‘Hypnosis was effective in reducing oral pain for patients undergoing marrow transplantation. The CBT intervention was not effective in reducing symptoms measured.’ |

| Everett, 1993 | Parallel 2 Not reported |

Burn debridement 32/32 |

1) Hypnosis (25 min) before debridement +standard care 2) Hypnosis (25 min) intervention prior to debridement + Lorazepam + standard care |

1) standard care 2) hypnosis attention control: time and attention (25 min) + standard care |

1) VAS self-report 2) VAS nurse observation 3) pain medication stability |

1) No significant intergroup or within group differences 2) No significant intergroup or within group differences 3) Pain medication was equivalent across four groups. |

‘The results are argued to support the analgesic advantages of early, aggressive opioid use via PCA [patient-controlled analgesia apparatus] or through careful staff monitoring and titration of pain drugs.’ |

| Lambert, 1996 | Parallel design 2 Not reported |

Variety of elective surgical procedures 52/50 |

1 training session (30 min) 1 week before surgery, where children were taught guided imagery. Posthypnotic suggestions for better surgical outcome. (n =26) | Attention control: Equal amount of time spent with a research assistant discussing surgery and other topics of interest. (n=26) | 1) pain reported each hour after surgery on a numerical rating scale (0–10) 2) total analgesics used postoperatively 3) self-report anxiety (STAIC) |

1) lower pain ratings in the hypnosis group (p<.01) 2) no significant difference in analgesic use between groups 3) no significant difference in anxiety between groups |

‘This study demonstrates the positive effects of hypnosis/guided imagery for the pediatric surgical patient.’ |

| Lang, 1996 | Parallel design 3 Not reported |

Radiological procedures 30/30 |

Instruction in self Hypnosis to be used during operation + standard care (n=16) | Standard care (n=14) | 1) 0–10 numeric rating scale at baseline, at ‘20 min into every 40-min interval, and before leaving the intervention table’ 2) Blood pressure 3) Intravenous PCA4 |

1) Hypnosis participants reported significantly less pain than controls (p<.01) 2) No significant intergroup differences with regard to increases in blood pressure. 3) Controls self-administered significantly more medication than hypnosis participants (p<.01). |

‘Self-hypnotic relaxation can reduce drug use and improve procedural safety’ |

| Smith, 1996 | Crossover-design 2 Not reported |

venipuncture or infusaport access 36/27 |

Training for the child and parent to use a favorite place hypnotic induction where the parent and child go on an imaginary journey to a location of the child’s choosing during the medical procedure. Daily practice for 1 week before the procedure. (n = 36) | Training for the child and parent to apply distraction technique using a toy during the medical procedure. Daily practice for 1 week before the procedure. (n = 36) | 1) Children’s Global Rating Scale (CGRS) of pain by the patient 2) Children’s Global Rating Scale (CGRS) of anxiety by the patient 3) pain Likert scale by the parent 4) anxiety Likert scale by the parent 5) Independent observer-reported anxiety 6) Observational Scale of Behavioral Distress-Revised (OSBD-R) |

1) CGRS pain rating was lower in the hypnosis condition (p<.001), especially in high hypnotizables. 2) CGRS anxiety rating was lower in the hypnosis condition (p<.001), especially in high hypnotizables. 3), 4) and 5) parent reported pain and anxiety, and observer reported anxiety showed the same pattern (ps<.001). 6) no significant main effect of condition reported for OSBD-R scores. |

‘Hypnosis was significantly more effective than distraction in reducing perceptions of behavioral distress, pain, and anxiety in hypnotizable children.’ |

| Enqvist, 1997 | Parallel design 3 Not reported |

Surgical removal of third mandibular molars 72/69 |

20 min Hypnosis via audiotape one week prior to surgery with recommendations for daily listening + standard care (n= 33) | Standard care (n= 36) | postoperative analgesic use | Of participants randomized to hypnosis, 3% consumed three or more equipotent doses of postoperative analgesics in comparison to 28% of controls. | ‘The preoperative use of a carefully designed audiotape is an economical intervention, in this instance with the aim to give the patient better control over anxiety and pain. A patient-centered approach, together with the use of hypnotherapeutic principles, can be a useful addition to drug therapy. A preoperative hypnotic technique audiotape can be additionally helpful because it also gives the patient a tool for use in future stressful situations.’ |

| Faymonville, 1997 | Parallel design 2 Yes |

Plastic surgery 60/56 |

Hypnosis (just proceeding and during surgery) + standard care (n=31) | Emotional support (during surgery) + standard care (n=25) | 1) Intraoperative pain VAS 2) postoperative pain VAS (self-report) 3) intraoperative pain medication requirements |

1) Intraoperative was significantly lower among hypnosis participants than controls (p<.02). 2) Hypnosis participants reported significantly less postoperative pain than controls (p<.01) 3) Hypnosis participants required significantly less intraoperative midazolam (p<.001) and alfentanil (p<.001) than controls. |

‘(…) hypnosis provides better perioperative pain and anxiety relief, allows for significant reduction in alfentanil and midazolam requirements, and improves patient satisfaction and surgical conditions as compared with conventional stress reducing strategies support in patients receiving conscious sedation for plastic surgery.’ |

| Patterson, 1997 | Parallel Design 4 Not reported |

Burn debridement 63/57 |

1) hypnosis (25 min) prior to debridement +standard care | 1) attention and information control + standard care | 1) 100 mm VAS self-report 2) 100 VAS nurse observation 3) pain medication stability |

1a) No significant intergroup differences in the total sample. 1b) Hypnosis participants experienced less pain (p<.05) among patients with high baseline pain levels 2a) observer ratings indicated less pain among hypnosis participants than controls (p<.05) 2b) no intergroup differences among patients with high baseline pain according to nurses 3) no significant intergroup differences (comparing all patients or high pain patients) |

‘The findings provided further evidence that hypnosis can be a useful psychological intervention for reducing pain in patients who are being treated for a major burn injury. However, the findings also indicate that this technique is likely more useful for patients who are experiencing high levels of pain.’ |

| Liossi, 1999 | Parallel design 3 Not reported |

Bone marrow aspirations 30/30 |

Hypnosis (3, 30 min sessions prior to procedure, n= 10) | 1) Standard care (n = 10) 2) Cognitive behavioral (CB) coping skills (3, 30 min sessions prior to procedure, n= 10) |

1) PBCL5 (behavioral observation, pain, during one BMA6 at baseline and during BMA after interventions) 2) 6-point faces rating scale (self-report, pain, during one BMA at baseline and during BMA after interventions) |

1) PBCL indicated hypnosis (p=.001) and CB patients (p = .003) were less distressed than controls. Hypnosis participants also had less distress than CB (p = .025) participants. 2) Hypnosis participants (p = .005) or CB (p = .008) reported decreased pain in comparison to baseline that was not observed in controls. In addition, self-reported pain was less among hypnosis participants (p=.001) and CB participants (p=.002) than controls. There were no significant group differences of self-reported pain between hypnosis and CB participants. |

‘Hypnosis and CB were similarly effective in the relief of pain….It is concluded that hypnosis and CB coping skills are effective in preparing pediatric oncology patients for bone marrow aspiration.’ |

| Lang, 2000 | Parallel design 3 Not reported |

Percutaneous vascular and renal procedures 241/241 |

Guided self- hypnotic relaxation during surgery + standard medical care (n=82) | 1) Standard care (n=79) 2) structured attention during surgery + standard medical care(n=80) |

1) 0–10 verbal scales (pain, before surgery and every 15 min during it) 2) Amount of medication requested during procedure |

1) Participants experienced a linear increase in pain throughout the operation if randomized to attention (p= .0425) or standard care (p<.0001). However, hypnosis participants did not experience a significant pain increase. 2) Medication usage was significantly greater among participants randomized to standard care (1.9 units) in comparison to hypnosis (0.9 units) or structured attention participants (0.8 units). |

‘Structured attention and self-hypnotic relaxation proved beneficial during invasive medical procedures. Hypnosis had more pronounced effects on pain and anxiety reduction, and is superior, in that it also improves hemodynamic stability.’ |

| Wright, 2000 | Parallel design 1 Not reported |

Burn debridement 30/30 |

Hypnosis (15 min) prior to debridement procedures + standard care | Standard care | 1) Self report of sensory and affective pain during burn care 2) retrospective self-report of pain ratings after burn care 3) medication consumption |

1a) Significant pre-post decreases of sensory (p<.001) and affective (p<.001) pain were seen among hypnosis participants by end of first procedure. 1b) Self report of sensory (p<.05) and affective (p<.05) pain were lower among hypnosis participants than controls after the second debridement. 3) In the hypnosis group, consumption of paracetamol (p<.01) and codeine (p.=.01) decreased but remained unchanged in controls. |

Hypnosis is ‘a viable adjunct to narcotic treatment for pain control during burn care.’ |

| Montgomery, 2002 | Parallel design 1 Not reported |

Excisional breast biopsy 20/20; + 20 healthy controls | Hypnosis (10 min hypnotic induction before the procedure, n=20) | Standard-care (n=20) Healthy group (n=20) |

10cm VAS (pain). | Hypnosis group demonstrated decreased post-surgery pain in comparison to control (p<.001) | ‘The results of the present study revealed that a brief hypnosis intervention can be an effective means to reduce postsurgical pain and distress in women undergoing excisional breast biopsy. Postsurgical pain was reduced in patients receiving hypnosis relative to a standard care control group.’ |

| Liossi, 2003 | Parallel design 2 Not reported |

Lumbar punctures (LP) 80/80 |

1) Direct hypnosis (1, 40 minute session + administration directly before and during 2LP + self-hypnosis instruction + standard care, n=20) 2) Indirect hypnosis (1, 40 minutes session + administration directly before and during 2LP + self- hypnosis instruction + standard care, n=20) |

1) Standard care (n= 20) 2) ) Attention control (40 minutes session + standard care, n=20) |

1) PBCL (behavioral observation, pain, at baseline and during 2 LP with therapist directed interventions + 3 LP with self-hypnosis interventions) 2) 6-point faces rating scale (self-report, pain, during baseline, 2 consecutive LPs with therapist interventions + 3 LPs with self-hypnosis only) |

1) Observed distress in hypnosis group decreased significantly during intervention (p <.001) and was significantly lower than that of controls (p<.001). In addition, behavioral distress was lower among treatment groups during 1st and 3rd LPs using self- hypnosis than among controls (p<.001 for all comparisons between groups). However, distress increased to baseline levels at 6th LP using self-hypnosis. There were no significant intragroup differences between the treatment or control groups. 2) During the intervention phase, hypnosis participants experienced significantly less pain than attention (p<.02) and standard care (p<.001) controls. Pain decreases continued during 1st and 3rd LPs using self-hypnosis but increased to levels baseline levels by the 6th LP with self-hypnosis. No significant intragroup differences between the treatment or control groups. |

‘(…) Hypnosis is effective in preparing pediatric oncology patients for lumbar puncture, but the presence of the therapist may be critical.’ |

| Harandi, 2004 | Parallel design 0 Not reported |

Physiotherapy for burns 44/44 |

Hypnosis once a day for a period of 4 days, n=22) | Standard-care (n=22) | 100mm VAS7 (pain) | Hypnosis participants experienced less pain physiotherapy - related pain in comparison to controls (p<.001) | ‘Hypnosis is recommended as a complementary method in burns physiotherapy.’ |

| Massarini, 2005 | Parallel design 1 Not reported |

Surgical operation 42/42 |

15 – 30 min of Hypnosis 24 hours prior to operation (n=20) | Standard care (n=20) | 0–10 numeric rating scale combined with a scale of facial expressions (Faces Pain Rating Scale) recorded each day postoperatively for 4 days to assess affective and sensory pain | 1a) Hypnosis participants reported less pain intensity on day 1(p = .006) and 2 (p= .003) following their operation in comparison to controls. However, pain intensity in the hypnosis group was comparable to that of controls on day 3 and 4. 1b) Affective pain was also less among hypnosis participants in comparison to controls on day 1 (p=.010) and 2 (p=.010) postoperatively, but was equivocal on day 3 (p=.204) and 4 (p=.702) |

‘This controlled study showed that brief hypnotic treatment carried out in the preoperative period leads to good results with surgery patients in terms of reducing anxiety levels and pain perception.’ |

| Lang, 2006 | Parallel design 3 Not reported |

Breast biopsy 240/236 |

Hypnosis during procedure + empathetic attention (n= 78) | 1) Standard care (n = 76) 2) Structured emphatic attention during procedure (n= 82) |

1) Verbal 0–10 analog scale (intraoperative every 10 min) | Intraoperative pain increased significantly for all groups (p<.001). However, the pain increase among hypnosis participants was less steep than that of empathy (p = .024) or standard care (p = .018) participants. | ‘(…) while both structured empathy and hypnosis decrease procedural pain and anxiety, hypnosis provides more powerful anxiety relief without undue cost and thus appears attractive for outpatient pain management.’ |

| Liossi, 2006 | Parallel design 4 Yes |

Lumbar punctures 45/45 |

1) EMLA +Hypnosis (approximately 40 min session + self- hypnosis training, n= 15) | 1) EMLA =15 2) EMLA + Attention (approximately 40 minute session, n= 15) |

1) The Wong–Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale (self-report) 2) PBCL * Measures were collected 3 times - during therapist led intervention (time 2) – - during self-hypnosis intervention (time 3 and 4) |

1) During all 3 measurement times, hypnosis participants were found to report less pain that the attention controls: (p<.001) for times 2 and 3; (p<.002) for time 4. In addition, hypnosis participants experienced less pain than EMLA only controls: (p<.001) for times 2, 3, and 4 2) At times 2, 3, and 4, participants randomized to EMLA + hypnosis appeared significantly less distressed than those of the EMLA group (p<.001) or the EMLA + attention group (p<.001). There were no significant intergroup differences between controls. |

‘(…) self-hypnosis might be a time- and cost-effective method that nevertheless extends the benefits of traditional hetero-hypnosis.’ |

| Marc, 2007 | Parallel design 3 Not reported |

Abortion 30/29 |

Hypnosis (20 min before and during procedure, n=14) | Standard-care (n=15) | 1) Request for N2O sedation. 2) 11-point verbal numerical scale used during operation |

1) 36% of hypnosis participant needed N2O sedation compared to 87% of controls (p<.01). 2) No significant differences. |

‘(…) hypnosis can be integrated into standard care and reduces the need for N2O in patients undergoing first-trimester surgical abortion.’ |

| Montgomery, 2007 | Parallel design 4 Not reported |

Breast cancer surgery 200/200 |

Hypnosis (15 minute, pre-surgical intervention, n= 105) | Attention control (15 minute pre- surgical intervention, n= 95) | 1) Intraoperative medication use 2) 0–100 VAS pain intensity and unpleasantness |

1) Patients randomized to receive hypnosis required less Lidocaine (p<.001) and Propofol (p<.001) interoperatively than controls. Utilization of Fentanyl and Midazlam was not statistically different between groups, nor was use of postoperative analgesics. 2) Hypnosis participants reported also reported significantly less pain intensity (p<.001) and pain unpleasantness (p<.001) than controls. |

‘Overall, the present data support the use of hypnosis with breast cancer surgery patients.’ |

| Marc, 2008 | Parallel design 3 Not reported |

Abortion 350/347 |

Hypnotic analgesia (20 min before and during procedure, n=172) | Standard-care (n=175) | 1) Use of sedation. 2) 0–100 visual numeric scales (two separate ratings during operation) |

1) Hypnosis participants required less IV analgesia than controls (p <.0001) 2) Hypnosis participants did not report significant pain increase during suction evaluation. | ‘Hypnotic interventions can be effective as an adjunct to pharmacologic management of acute pain during abortion.’ |

| Liossi, 2009 | Parallel design 4 Yes |

Venipuncture 45/45 |

EMLA8 + hypnosis (15 min) prior to first venipuncture + self-hypnosis instruction (n= 15) | 1) EMLA (n=15) 2) EMLA + attention (15 minutes) prior to first venipuncture (n= 15) |

1) 100 mm VAS 2) PBCL (three times following baseline - during preparation, needle insertion, and post procedure) |

1a) Venipuncture 1:Self-reported pain was significantly less in hypnosis participants than in attention controls (p<.001) who reported significantly less pain than EMLA only controls (p<.04) 1b) Venipuncture 2& Venipuncture 3: Self-reported pain was significantly lower among hypnosis participants than attention (p<.001) or EMLA only controls (p<.001). There were no significant intergroup differences between controls. 2a) Venipuncture 1: Hypnosis participants displayed less observable distress than attention (p<.001) controls, who appeared less distressed than EMLA only (p<.001) controls. 2b) Venipuncture 2& 3: Hypnosis participants again displayed significantly less observable distress than attention controls (p <.001) in both venipunctures. Attention controls also appeared less distressed than EMLA only controls during both venipuncture 2 (p=.025) and 3 (p = .008). |

‘(…) the use of self-hypnosis prior to venipuncture can be considered a brief, easily implemented and an effective intervention in reducing venipuncture-related pain.’ |

| Mackey, 2010 | Parallel design 4 Not reported |

Molar extraction 91/91 |

Hypnosis + relaxing background music during surgery + standard care (n=46) | Relaxing background music during surgery + standard care (n= 54) | 1) postoperative pain - 10cm VAS 2) intraoperative medication use 3) postoperative prescription analgesic used |

1) Postoperative pain was significantly less among hypnosis participants than controls (p<.001). 2) Control participants required significantly more intraoperative medication than hypnosis participants (p<.01). 3) The use of postoperative analgesics was significantly less among hypnosis participants than controls (p<.01). |

‘(…) the use of hypnosis and therapeutic suggestion as an adjunct to intravenous sedation assists patients having third molar removal in an outpatient surgical setting.’ |

| Snow, 2012 | Parallel design 1 Not reported |

Bone marrow aspirates and biopsies 80/80 |

Hypnosis (15 min before and during the procedure) + standard care (n= 41) | Standard-care (n=39) | 100mm VAS (pain, anxiety) | No significant between group differences in pain ratings. | ‘(…) brief hypnosis concurrently administered reduces patient anxiety during bone marrow aspirates and biopsies but may not Adequately control pain.’ |

‘Due to changes in medical treatment protocols which eliminated or significantly reduced the number of BMA/LP’s done with patients, only 20 of the original group of 42 subjects who initially volunteered completed the study.’ Page 183

VAS, visual analog scale

MPQ, McGill Pain Questionnaire

PCA, Intravenous patient-controlled analgesia

PBCL, Procedure Behavior Checklist

BMA, Bone marrow aspiration

VAS, visual analog scale

EMLA, eutectic mixture of local anesthetics

In the majority of the studies reviewed, more than one measure was used to assess pain. The most frequently used pain related outcome was subjective pain intensity (used in 27 studies), followed by analgesic use or pain medication stability (15 studies), behavioral signs of pain (13 studies), anxiety (five studies), pain unpleasantness or an affective component of pain (three studies), and cardiovascular measures (two studies). Subjective pain intensity was measured by visual analog scale (VAS) in most instances (12 studies). However, single item numeric rating scales (nine studies), pictorial rating scales (e.g., using pictures of emotional faces, five studies), and pain questionnaires (McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Children’s Global Rating Scale (CGRS), two studies) were also applied. Most of the studies compared the effectiveness of hypnosis to standard care (20 studies), while some studies also utilized attention control (11 studies) or compared the effectiveness of hypnosis to another type of active treatment, like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT, three studies), distraction (three studies), emotional support from the therapist (one study), play therapy (one study) or relaxing music (one study).

From a total of 45 measurements comparing hypnosis to standard care, the hypnosis group had significantly lower pain ratings in 28 measurements (62%), while hypnosis decreased pain compared to attention control in 16 out of 30 measurements (53%). Furthermore, in 16 out of 30 (53%) measurements, hypnosis yielded significantly better results when compared with other adjunct pain therapies. Specifically, from two measurements, there was no difference between hypnosis and play therapy; in two out of seven measurements, hypnosis was significantly better than CBT; in eight out of 15 measurements, hypnosis was superior to distraction1; three out of three measurements confirmed the benefits of hypnosis during surgery over emotional support; and similarly, three out of three measures yielded significantly better results for hypnosis combined with relaxing music compared to relaxing music alone.

In the included studies, hypnosis was used for pain management in bone marrow aspiration (seven studies), lumbar puncture (five studies), burn debridement or other burn care (five studies), surgical procedures (eight studies), or other medical procedures (abortion, venipuncture, radiological procedures, angioplasty; seven studies). Only six studies applied more than one session of hypnosis, and most of the hypnosis sessions were shorter than 30 minute, or they lasted as long as the procedure itself. Interventions were either administered days before the medical procedure (eight studies), preoperatively on the day of the procedure (seven studies), both days before the procedure and preoperatively (two studies), during the procedure (six studies), or both preoperatively and during the procedure (six studies). Table 2 displays an overview of effectiveness by showing the percentage of measures in which hypnosis significantly decreased pain as compared to different control conditions by different intervention characteristics (timing, length, dose), and by medical procedures. Hypnotizability was assessed in seven studies, four of which reported significant positive association between the level of hypnotic susceptibility and pain-related outcomes.

Table 2.

Effectiveness of hypnosis displayed by various comparison groups and study and intervention characteristics

| total number of studies | total number of measurements | sign. effect percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| control condition | |||

| hypnosis is better than standard care control | 20 | 45 | 62% |

| hypnosis is better than attention control | 11 | 30 | 53% |

| hypnosis is better than other active treatment | 9 | 30 | 53% |

| procedure type | |||

| bone marrow aspiration | 4 | 10 | 30% |

| lumbar puncture | 2 | 5 | 60% |

| burn debridement or other burn care | 5 | 12 | 42% |

| surgical procedure | 6 | 12 | 75% |

| other medical procedures | 6 | 14 | 69% |

| amount of sessions | |||

| more than 1 sessions | 3 | 5 | 80% |

| 1 sessions | 20 | 50 | 54% |

| intervention length | |||

| 30 minutes or longer | 6 | 16 | 56% |

| shorter than 30 minutes | 11 | 25 | 68% |

| lasting as long as the procedure | 5 | 14 | 36% |

| intervention timing | |||

| presentation days before the procedure | 6 | 15 | 67% |

| pre-operative presentation | 13 | 34 | 47% |

| intra-operative presentation | 8 | 20 | 45% |

Note: sign. effect percentage shows the percentage of measures in which hypnosis groups had significantly lower pain scores than the comparison group in relation to the total number of measures. For the assessment of procedure type, amount of sessions, intervention length and intervention timing comparison groups were attention control or standard care groups.

Discussion

The evidence for the effectiveness of hypnosis as an adjunct therapy for management of acute pain was evaluated. Overall, results from RCTs identified in the review process suggest that hypnosis reduces acute pain associated with medical procedures.

Pain was most often measured with a single VAS score. Although this scale is easy to administer and has low time-cost from the respondents, its acceptability and psychometric properties are questionable when used with in a pediatric or geriatric population (e.g., Hjermstad et al., 2011; Stinson, Kavanagh, Yamada, Gill, & Stevens, 2006; van Dijk, Koot, Saad, Tibboel, and Passchier, 2002). Furthermore, VAS and the simple numerical rating scales applied in most studies are one-dimensional and usually only evaluate pain intensity, which might be problematic because the affective component of pain remains unassessed this way. Specifically, according to dissociation theories, hypnotic analgesia does not result in a simple reduction of pain sensation. Rather, it induces dissociation from pain and the decoupling of pain intensity and pain unpleasantness. For example, according to Rainville, Carrier, Hofbauer, Bushnell, and Duncan (1999), sensory and affective dimensions of pain are largely independent in a hypnotic state, and these factors could be differentially modulated with different hypnotic suggestions. Brain imaging studies also support the notion that hypnosis can affect subjective pain intensity through the somatosensory cortex (Hofbauer, Rainville, Duncan, & Bushnell, 2001) and pain unpleasantness through the anterior cingulate cortex (Rainville, Duncan, Price, Carrier, & Bushnell, 1997) differentially. Thus, suggestions devised to decrease pain unpleasantness may leave pain intensity ratings unaffected, meaning that the pain scales should be synchronized with the intervention scripts in all studies, especially if a one-dimensional scale is to be applied as a pain measure.

Evidence supporting the effectiveness of hypnosis is strongest when compared to standard care control, and beneficial effects are still apparent when hypnosis is contrasted to attention control. However, the strength of evidence of clinical trials using these two control conditions have been challenged (Jensen & Patterson, 2005; Patterson & Jensen, 2003). In spite of the recommendation of Jensen and Patterson (2005), eight out of nine studies published after this insightful paper still use standard care control or attention control instead of a “minimally effective treatment.” This makes it more difficult to fully establish the real efficacy of hypnosis, because of the possible ‘contamination’ by non-specific treatment effects (i.e. expectancy). It also makes it difficult for researchers to compare the effectiveness of hypnosis to other medical treatments that are usually evaluated with placebo control. Nevertheless, there are some studies directly contrasting the effectiveness of hypnosis and other adjunct therapies for pain; expectancy bias is less likely in such comparisons. Based on the studies in this review, hypnosis seems to be at least as effective as cognitive behavioral approaches and play therapy, while hypnosis with relaxing music was more effective than relaxing music alone, intraoperative hypnosis was also more effective than intraoperative emotional support, and in most instances hypnosis produced better results than distraction.

Included studies evaluated the effectiveness of hypnosis for pain control during bone marrow aspiration, lumbar puncture, burn care, surgical procedures and other potentially painful medical procedures like radiological procedures, abortion, and venipuncture. While there were reports of some beneficial effect for all of these procedures, the highest success rate was demonstrated in hypnosis for surgical procedures, with 75% of measures showing significantly beneficial results. This finding is in line with numerous previous reviews showing that hypnosis is a successful adjunctive treatment for the prevention of surgical side-effects (Flammer & Bongartz, 2003; Flory, Martinez Salazar, & Lang, 2007; Kekecs, Nagy, & Varga, in press; Montgomery, David, Winkel, Silverstein, & Bovbjerg, 2002; Schnur, Kafer, Marcus, & Montgomery, 2008; Tefikow et al., 2013; Wobst, 2007). We have to note here that most of the studies included in this review assess hypnoanalgesia for minor surgical procedures. A recent meta-analysis (Kekecs et al., in press) also showed that hypnosis is likely to reduce postoperative pain for minor procedures, but it failed to find conclusive evidence to support the effectiveness of postoperative hypnotic analgesia in major surgeries. The authors of that meta-analysis speculate that hypnoanalgesic effects might not be sufficient for controlling pain in major surgeries, or, that they may be masked by rigorous pharmacological pain control regimes used after major procedures. Whichever is the case, our present review provides additional support for the benefits of perioperative hypnosis in minor surgeries. On the other hand, our review showed that studies on bone marrow aspiration and burn care reported the lowest percentage of significant effects from all the procedure types. Patterson and Jensen (2003) also found inconsistent results on the effects of hypnosis for burn care. Results of Patterson, Adcock and Bombardier (1997) suggest that initial levels of burn pain might be a moderator of effectiveness. Specifically, patients with higher baseline pain levels might be more motivated and more compliant, and additionally more able to dissociate, than patients with low burn pain.

Interventions with more than one hypnosis session reported more significant effects than did studies involving only one session; studies in which hypnosis was applied at least in part before the day of the procedure seemed to be more successful than those applying the intervention on the day of the procedure (either before or during procedure), and hypnosis interventions shorter than 30 minutes produced the best results. The concordance between the effectiveness of multiple intervention sessions and presentation before the day of the procedure is not surprising as, in multi-session interventions, sessions are usually not administered on the same day. Consequently, starting the preparation of patients early with several hypnosis sessions seems to be the best approach. However, at this point, we cannot tell if the earliness of the preparation or the multitude of sessions is the effective component here. Interpretations are also limited by the fact that most studies did not systematically vary moderating factors like number of hypnosis sessions, intervention length, and intervention timing. Thus, we can only draw indirect inferences. Systematic contrast of these intervention characteristics is needed. Future studies should also investigate whether the possibility of practice at home plays a role in the efficacy of ‘early starting’ interventions.

Several previous studies evaluated the economical properties of hypnosis as an adjunct treatment for medical procedures (e.g., Disbrow, Bennett, & Owings, 1993; Lang et al., 2006; Lang & Rosen, 2002; Montgomery et al., 2007). These studies demonstrated that hypnosis results in a significant cost-offsetting even when the cost of the intervention is accounted for, mainly due to decreased procedure times, fewer complications, lower chance of over-sedation, and shorter hospital stay after the procedures. The fact that most of the studies in the present review achieved beneficial effects with using merely one hypnosis session also suggests cost-effectiveness. However, as stated before, it seems that multiple sessions may enhance effectiveness. Future studies should evaluate the added benefits of multiple hypnosis sessions in lite of the increased intervention costs. Our results also showed that hypnosis sessions were usually shorter than 30 minutes, and that these short interventions produced the highest percentage of beneficial results.

It is also a question of economic value whether hypnoanalgesia is beneficial only for patients with high hypnotic susceptibility, or if it can be used with every patient. Earlier studies advocated the importance of hypnotizability as a determinant of hypnotically achievable analgesia (e.g., Freeman, Barabasz, Barabasz, & Warner, 2000; Montgomery, DuHamel, & Redd, 2000). Although this might be true in laboratory settings, a recent meta-analysis argues that the variance in outcome explained by hypnotic susceptibility is so small (6%) that it is of little to no clinical importance (Montgomery, Schnur, & David, 2011). In the vast majority of the studies included in our review, participants were not screened for hypnotic susceptibility, and none of the seven studies measuring hypnotizability selected participants based on this score. Four of these seven studies reported significant associations between outcomes and hypnotizability. However, in spite of the lack of selection for high hypnotizables during patient enrollment, most of the studies in our review yielded a significant beneficial effect, which corresponds with the conclusions of previous reviews indicating that most patients are “hypnotizable enough” to benefit from hypnotic interventions (Montgomery, David, et al., 2002; Montgomery et al., 2011). Based on our review, we argue that hypnoanalgesia is an effective and treatment for acute procedural pain which can be applied in a large variety of medical areas and patient populations. Thus detailed guides of application incorporating recent research findings are needed to make the technique more generally accessible for clinicians (e.g., Patterson, 2010).

Hypnosis has been defined as a state of consciousness involving focused attention and reduced peripheral awareness characterized by an enhanced capacity for response to suggestion (Elkins, Barabasz, Council, & Spiegel, 2015). All of the included studies used hypnosis in which focused attention, guided imagery and analgesic suggestion are coupled with relaxation. Relaxational hypnosis is convenient because in most medical procedures patients are required to lie or sit still and thus relaxation and hypnosis can be continued during the procedure as well. However according to laboratory studies, hypnoanalgesia can also be achieved by active alert hypnosis in which hypnosis is performed during intense physical exercise of the subject (Bányai & Hilgard, 1976; Miller, Barabasz, & Barabasz, 1991). This is a feature that is yet to be utilized in medical hypnoanalgesia studies. Good candidates for using this technique might be radiological procedures requiring physical exercise as a stress test (e.g., some of the coronary artery imaging techniques).

Limitations

Although 75% of the studies had a methodological quality score of two or higher, only five papers got the maximal score of four during methodological evaluation. This shows that although methodological quality of the study pool is not poor, there is still a considerable chance that results are biased. Even more so, as the Jadad score itself is only sensitive to a limited set of possible methodological biases (Berger & Alperson, 2009), one of which (blinding of participants) was already ruled out of scoring because of the nature of hypnosis interventions. Furthermore, the presence of publication bias is also a common risk in the evaluation of clinical research, although according to Easterbrook, Gopalan, Berlin, and Matthews (1991), randomized controlled trials are less prone to it. Thus, simple pooling of effects of trials found during the literature search is likely to result in overestimation of the real effects. Further bias can be introduced by the pooling of measurements across different studies, as certain studies with a higher number of measurements can have a greater influence on the data. We also have to note that there is a chance that some relevant papers may have been missed during our literature search.

Conclusions

Results from randomized controlled clinical trials suggest that hypnosis decreases acute procedural pain, and is at least as effective as other complementary therapies. Hypnotic analgesia seems to be especially effective in minor surgical procedures. Furthermore, interventions started earlier than the day of the procedure and using more than one hypnosis sessions were most effective. However, further methodologically rigorous studies applying minimally effective control conditions and systematic control of intervention dose and timing are required to decrease risk of bias. Hypnosis interventions may affect subjective pain intensity and pain unpleasantness differentially. Thus, hypnotic suggestions and pain measures should be carefully matched. Also, additional research is needed to more fully evaluate the effectiveness of hypnotic interventions in contrast to non-hypnotic therapies, devise credible placebo control conditions, and determine the effect of potential moderators such as dose (i.e., number of sessions) and hypnotizability.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Vicki Patterson, Savannah Gosnell, Luzie Fofonka-Cunha and Peter Jiang for their assistance in obtaining articles, preparation of tables and editing references.

Funding

Dr. Elkins was supported by grant # U01AT004634 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Although Kuttner, Bowman and Teasdale (1988) showed the superiority of hypnosis compared to distraction in some cases for pain and anxiety reduction, these results were only significant in a subsample (younger children), thus they were counted as not significantly better overall.

No conflicts of interest exist.

References

- Accardi MC, Milling LS. The effectiveness of hypnosis for reducing procedure-related pain in children and adolescents: a comprehensive methodological review. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32(4):328–339. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askay SW, Patterson DR, Jensen MP, Sharar SR. A randomized controlled trial of hypnosis for burn wound care. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2007;52(3):247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Bányai EI, Hilgard ER. A comparison of active-alert hypnotic induction with traditional relaxation induction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1976;85:218–224. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger VW, Alperson SY. A general framework for the evaluation of clinical trial quality. Reviews on Recent Clinical Trials. 2009;4(2):79–88. doi: 10.2174/157488709788186021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers KS. Imagination and dissociation in hypnotic responding. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 1992;40:253–275. doi: 10.1080/00207149208409661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaves JF. Hypnosis in pain management. In: Lynn SJ, Rhue JW, Kirsh I, editors. Handbook of Clinical Hypnosis. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1993. pp. 511–532. [Google Scholar]

- Cyna AM, McAuliffe GL, Andrew MI. Hypnosis for pain relief in labour and childbirth: a systematic review. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2004;93(4):505–511. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disbrow E, Bennett H, Owings J. Effect of preoperative suggestion on postoperative gastrointestinal motility. Western Journal of Medicine. 1993;158(5):488–492. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrook PJ, Gopalan R, Berlin J, Matthews DR. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet. 1991;337(8746):867–872. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90201-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins GR. Hypnotic Relaxation Therapy: Principles and Applications. Washington, DC: Springer; 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins GR, Barabasz AF, Council JR, Spiegel D. Advancing research and practice: The Revised APA Division 30 Definition Of Hypnosis. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 2015;63:1–9. doi: 10.1080/00207144.2014.961870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins GR, Jensen MP, Patterson DR. Hypnotherapy for the management of chronic pain. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 2007;55:275–287. doi: 10.1080/00207140701338621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enqvist B, Fischer K. Preoperative hypnotic techniques reduce consumption of analgesics after surgical removal of third mandibular molars: a brief communication. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 1997;45:102–108. doi: 10.1080/00207149708416112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett JJ, Patterson DR, Burns GL, Montgomery B, Heimbach D. Adjunctive interventions for burn pain control: comparison of hypnosis and ativan: the 1993 Clinical Research Award. Journal of Burn Care and Research. 1993;14(6):676–683. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199311000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faymonville ME, Mambourg P, Joris J, Vrijens B, Fissette J, Albert A, Lamy M. Psychological approaches during conscious sedation. Hypnosis versus stress reducing strategies: a prospective randomized study. Pain. 1997;73:361–367. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00122-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flammer E, Bongartz W. On the efficacy of hypnosis: a meta-analytic study. Contemporary Hypnosis. 2003;20(4):179–197. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming S, Rabago DP, Mundt MP, Fleming MF. CAM therapies among primary care patients using opioid therapy for chronic pain. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2007;7(1):15. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flory N, Martinez Salazar GM, Lang EV. Hypnosis for acute distress management during medical procedures. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 2007;55:303–317. doi: 10.1080/00207140701338670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman R, Barabasz AF, Barabasz M, Warner D. Hypnosis and distraction differ in their effects on cold pressor pain. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis. 2000;43:137–148. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2000.10404266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay MC, Philippot P, Luminet O. Differential effectiveness of psychological interventions for reducing osteoarthritis pain: a comparison of Erickson hypnosis and Jacobson relaxation. European Journal of Pain. 2002;6(1):1–16. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2001.0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harandi AA, Esfandani A, Shakibaei F. The effect of hypnotherapy on procedural pain and state anxiety related to physiotherapy in women hospitalized in a burn unit. Contemporary Hypnosis. 2004;21(1):28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hilgard ER, Hilgard JR. Hypnosis in the Relief of Pain. Philadelphia, PA: Brunner/Mazel; 1994. Revised ed. [Google Scholar]

- Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, Caraceni A, Hanks GW, Loge JH, Kaasa S. Studies comparing Numerical Rating Scales, Verbal Rating Scales, and Visual Analogue Scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2011;41(6):1073–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofbauer RK, Rainville P, Duncan GH, Bushnell MC. Cortical representation of the sensory dimension of pain. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2001;86(1):402–411. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.1.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Controlled Clinical Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MP, Patterson DR. Control conditions in hypnotic-analgesia clinical trials: challenges and recommendations. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 2005;53:170–197. doi: 10.1080/00207140590927536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz ER, Kellerman J, Ellenberg L. Hypnosis in the reduction of acute pain and distress in children with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1987;12(3):379–394. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/12.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kekecs Z, Nagy T, Varga K. The effectiveness of suggestive techniques in reducing post-operative side effects: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesthesia and Analgesia. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000466. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuttner L, Bowman M, Teasdale M. Psychological treatment of distress, pain, and anxiety for young children with cancer. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1988;9(6):374–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert SA. The effects of hypnosis/guided imagery on the postoperative course of children. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 1996;17(5):307–310. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199610000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang EV, Benotsch EG, Fick LJ, Lutgendorf S, Berbaum ML, Berbaum KS, Spiegel D. Adjunctive non-pharmacological analgesia for invasive medical procedures: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;355(9214):1486–1490. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02162-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang EV, Berbaum KS, Faintuch S, Hatsiopoulou O, Halsey N, Li X, Baum J. Adjunctive self-hypnotic relaxation for outpatient medical procedures: a prospective randomized trial with women undergoing large core breast biopsy. Pain. 2006;126(1):155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang EV, Joyce JS, Spiegel D, Hamilton D, Lee KK. Self-hypnotic relaxation during interventional radiological procedures: Effects on pain perception and intravenous drug use. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 1996;44:106–119. doi: 10.1080/00207149608416074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang EV, Rosen MP. Cost Analysis of Adjunct Hypnosis with Sedation during Outpatient Interventional Radiologic Procedures 1. Radiology. 2002;222(2):375–382. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2222010528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liossi C, Hatira P. Clinical hypnosis versus cognitive behavioral training for pain management with pediatric cancer patients undergoing bone marrow aspirations. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 1999;47:104–116. doi: 10.1080/00207149908410025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liossi C, Hatira P. Clinical hypnosis in the alleviation of procedure-related pain in pediatric oncology patients. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 2003;51:4–28. doi: 10.1076/iceh.51.1.4.14064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liossi C, White P, Hatira P. Randomized clinical trial of local anesthetic versus a combination of local anesthetic with self-hypnosis in the management of pediatric procedure-related pain. Health Psychology. 2006;25(3):307–315. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liossi C, White P, Hatira P. A randomized clinical trial of a brief hypnosis intervention to control venepuncture-related pain of paediatric cancer patients. Pain. 2009;142(3):255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey EF. Effects of hypnosis as an adjunct to intravenous sedation for third molar extraction: A randomized, blind, controlled study. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 2009;58:21–38. doi: 10.1080/00207140903310782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marc I, Rainville P, Masse B, Verreault R, Vaillancourt L, Vallée E, Dodin S. Hypnotic analgesia intervention during first-trimester pregnancy termination: an open randomized trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;199(5):469.e461–469.e469. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marc I, Rainville P, Verreault R, Vaillancourt L, Masse B, Dodin S. The use of hypnosis to improve pain management during voluntary interruption of pregnancy: an open randomized preliminary study. Contraception. 2007;75(1):52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massarini M, Rovetto F, Tagliaferri C, Leddi G, Montecorboli U, Orifiammi P, Parvoli G. Preoperative hypnosis. A controlled study to assess the effects on anxiety and pain in the postoperative period. European Journal of Clinical Hypnosis. 2005;6(1):8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Miller MF, Barabasz AF, Barabasz M. Effects of active alert and relaxation hypnotic inductions on cold pressor pain. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:223–226. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery GH, Bovbjerg DH, Schnur JB, David D, Goldfarb A, Weltz CR, Price DD. A randomized clinical trial of a brief hypnosis intervention to control side effects in breast surgery patients. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2007;99(17):1304–1312. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery GH, David D, Winkel G, Silverstein JH, Bovbjerg DH. The effectiveness of adjunctive hypnosis with surgical patients: a meta-analysis. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2002;94(6):1639–1645. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200206000-00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery GH, DuHamel KN, Redd WH. A meta-analysis of hypnotically induced analgesia: How effective is hypnosis? International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 2000;48:138–153. doi: 10.1080/00207140008410045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery GH, Schnur JB, David D. The impact of hypnotic suggestibility in clinical care settings. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 2011;59:294–309. doi: 10.1080/00207144.2011.570656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery GH, Weltz CR, Seltz M, Bovbjerg DH. Brief presurgery hypnosis reduces distress and pain in excisional breast biopsy patients. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 2002;50:17–32. doi: 10.1080/00207140208410088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson DR. Clinical Hypnosis for Pain Control. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson DR, Adcock RJ, Bombardier CH. Factors predicting hypnotic analgesia in clinical burn pain. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 1997;45:377–395. doi: 10.1080/00207149708416139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson DR, Everett JJ, Burns GL, Marvin JA. Hypnosis for the treatment of burn pain. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:713–717. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson DR, Jensen MP. Hypnosis and clinical pain. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:495–521. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson DR, Ptacek J. Baseline pain as a moderator of hypnotic analgesia for burn injury treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:60–67. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainville P, Carrier Bt, Hofbauer RK, Bushnell MC, Duncan GH. Dissociation of sensory and affective dimensions of pain using hypnotic modulation. Pain. 1999;82(2):159–171. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainville P, Duncan GH, Price DD, Carrier B, Bushnell MC. Pain affect encoded in human anterior cingulate but not somatosensory cortex. Science. 1997;277(5328):968–971. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson J, Smith JE, McCall G, Pilkington K. Hypnosis for procedure-related pain and distress in pediatric cancer patients: A systematic review of effectiveness and methodology related to hypnosis interventions. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2006;31(1):70–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnur JB, Kafer I, Marcus C, Montgomery GH. Hypnosis to manage distress related to medical procedures: a meta-analysis. Contemporary Hypnosis. 2008;25(3–4):114–128. doi: 10.1002/ch.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JT, Barabasz AF, Barabasz M. Comparison of hypnosis and distraction in severely ill children undergoing painful medical procedures. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1996;43:187. [Google Scholar]

- Snow A, Dorfman D, Warbet R, Cammarata M, Eisenman S, Zilberfein F, Navada S. A randomized trial of hypnosis for relief of pain and anxiety in adult cancer patients undergoing bone marrow procedures. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2012;30(3):281–293. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2012.664261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson JN, Kavanagh T, Yamada J, Gill N, Stevens B. Systematic review of the psychometric properties, interpretability and feasibility of self-report pain intensity measures for use in clinical trials in children and adolescents. Pain. 2006;125(1):143–157. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syrjala KL, Cummings C, Donaldson GW. Hypnosis or cognitive behavioral training for the reduction of pain and nausea during cancer treatment: a controlled clinical trial. Pain. 1992;48(2):137–146. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90049-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefikow S, Barth J, Maichrowitz S, Beelmann A, Strauss B, Rosendahl J. Efficacy of hypnosis in adults undergoing surgery or medical procedures: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33:623–636. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk M, Koot HM, Saad HHA, Tibboel D, Passchier J. Observational visual analog scale in pediatric pain assessment: useful tool or good riddance? Clinical Journal of Pain. 2002;18(5):310–316. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall VJ, Womack W. Hypnotic versus active cognitive strategies for alleviation of procedural distress in pediatric oncology patients. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis. 1989;31:181–191. doi: 10.1080/00029157.1989.10402887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein EJ, Au PK. Use of hypnosis before and during angioplasty. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis. 1991;34(1):29–37. doi: 10.1080/00029157.1991.10402957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wobst AH. Hypnosis and surgery: past, present, and future. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2007;104(5):1199–1208. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000260616.49050.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright BR, Drummond PD. Rapid induction analgesia for the alleviation of procedural pain during burn care. Burns. 2000;26(3):275–282. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(99)00134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeltzer L, LeBaron S. Hypnosis and nonhypnotic techniques for reduction of pain and anxiety during painful procedures in children and adolescents with cancer. Journal of Pediatrics. 1982;101(6):1032–1035. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(82)80040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]