Abstract

In the thymus, antigen presenting cells (APCs) namely, medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTECs) and thymic dendritic cells (tDCs) regulate T cell tolerance through elimination of autoreactive T cells and production of thymic T regulatory (tTreg) cells. How the different APCs in the thymus share the burden of tolerazing the emerging T cell repertoire remains unclear. For example, while mutations that inhibit mTEC development or function associate with peripheral autoimmunity, the role of tDCs in organ-specific autoimmunity and tTreg cell production remains controversial. In this report we used mice depleted of mTECs and/or CD8α+ DCs, to examine the contributions of these cell populations in thymic tolerance. We found that while mice depleted of CD8α+ DCs or mTECs were normal or developed liver inflammation respectively, combined depletion of mTECs and CD8α+ DCs resulted in overt peripheral autoimmunity. The autoimmune manifestations in mice depleted of both mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs associated with increased percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the thymus. In contrast, while mTEC depletion resulted in reduced percentages of tTreg cells, no additional effect was observed when CD8α+ DCs were also depleted. These results reveal that: 1) mTECs and CD8α+ DCs cooperatively safeguard against peripheral autoimmunity through thymic T cell deletion; 2) CD8α+ DCs are dispensable for tTreg cell production, whereas mTECs play a non-redundant role in this process; 3) mTECs and CD8α+ DCs make unique contributions to tolerance induction that cannot be compensated for by other thymic APCs such as migratory SIRPα+ or plasmacytoid DCs.

Keywords: Medullary Thymic Epithelial Cells, Dendritic Cells, Autoimmunity, Regulatory T cells

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Tolerance to self-antigens occurs in the thymus and involves cross-talk between thymocytes and stromal or bone marrow (BM)-derived antigen presenting cells (APCs). Medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTECs) and thymic dendritic cells (tDCs) mediate negative selection of self-reactive T cells and thymic regulatory T cell (tTreg) production by presenting self-antigens to developing thymocytes [1, 2]. Three subsets of tDCs have been described in the mouse thymus [3]: CD11c+B220+ or PDCA1+ plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) and two subsets of CD11c+B220−or PDCA− conventional DCs (cDCs). cDCs can be further distinguished based on differential expression of CD8α and SIRPα/CD172a as migratory SIRPα+CD8α− cDCs (from here on referred to as SIRPα+) and SIRPα−CD8α+ classical cDCs (referred to as CD8α+). tDCs predominantly accumulate in the medulla and are sparsely detected in the cortex [4], although SIRPα+ cDCs were shown to be scattered in the cortex in close association with small blood vessels or inside perivascular regions [5]. While pDCs and the SIRPα+ cDCs are defined as migratory tDCs because they continuously enter the thymus from the circulation, CD8α+ cDCs, develop intrathymically and thus are defined as resident tDCs [6–8]. The exact roles of thymic APC subsets to tolerance induction remain unclear.

mTECs ectopically express tissue-restricted-antigens under the control of the transcription regulator Aire for the purpose of deleting self-reactive T cells [9]. Previous studies showed that BM-derived APCs in the thymus could present mTEC-derived antigens [10, 11]. A more recent study revealed that while mTECs and BM-derived APCs play redundant roles in negative selection and tTreg production, they nonetheless make distinct contributions to the T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire produced through these processes [12]. In contrast, results from a related study did not support a role for CD8α+ cDCs in tTreg cell production [13]. In addition, while defective antigen expression and presentation by mTECs results in autoimmunity development in mice and humans [14, 15], the role of tDCs in the development of peripheral autoimmunity is controversial [16, 17]. While Ohnmacht et al. showed that DC depletion led to impaired negative selection and fatal autoimmunity, Birnberg et al. found normal negative selection and no autoimmune manifestations following DC ablation. In addition, no spontaneous autoimmunity has been reported in mice lacking CD8α+ cDCs [18]. It has been proposed that the absence of autoimmunity in CD8α+ cDC-depleted mice may be to the fact that CD8α+ cells are required for both selection in the thymus and activation of the same TCR specificities in the periphery [9, 12].

In previous experiments we generated mice in which mTECs were depleted as a result of specific deletion of the TNF receptor associated factor 6 (Traf6) in TECs (Traf6ΔTEC mice) [19]. Given the conflicting data about the role of tDCs in the development of peripheral autoimmunity, the controversy of whether CD8α+ cDCs regulate tTreg cell production and to examine whether mTECs compensate in suppressing autoimmunity in mice depleted of CD8α+ cDCs, we generated mice lacking both mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs. We show that while the absence of mTECs associated with development of chronic inflammation in the form of autoimmune hepatitis in Traf6ΔTEC mice [19], combined depletion of mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs was required for development of severe, multi-organ autoimmunity. mTEC depletion significantly reduced tTreg cell production but no further effect on tTregs was observed in the absence of both mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs, whereas mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs cooperatively regulated T cell deletion. These results reveal that TCR specificities generated in the absence of both mTECs and thymic CD8α+ cDCs can contribute to the development of peripheral autoimmunity even in the absence of antigen presentation by peripheral CD8α+ cDCs. In addition, our findings suggest that mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs functionally cooperate to safeguard against autoimmunity through thymocyte deletion, whereas mTECs play a non-redundant role in tTreg cell production. Moreover, mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs make unique contribution to tolerance induction that cannot be compensated for by the remaining thymic pDCs and SIRPα+ cDCs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mice

All mice were on the C57BL/6 background maintained in the specific-pathogen-free barrier facility at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Traf6fl/fl/foxn1-Cre (Traf6ΔTEC) mice were previously described [19]. Irf8−/− and Batf3−/− mice were crossed with Traf6fl/fl/foxn1-Cre to obtain Irf8−/−/Traf6fl/fl/foxn1-Cre (referred to as Irf8−/−/Traf6ΔTEC) and Batf3−/−/Traf6fl/fl/foxn1-Cre (referred to as Batf3−/−/Traf6ΔTEC) double KO (dKO) mice. BM from Batf3−/− mice was used to create chimeric Traf6ΔTEC/Batf3−/− mice. Six to eight-week-old lethally irradiated (950 rads) WT and Traf6ΔTEC mice were reconstituted with 8×106 bone marrow cells isolated from WT and Batf3−/− mice. After four weeks of recovery, mice were weighed weekly for 6 weeks before analysis for organ-specific autoimmunity. GFPFoxp3 mice were a generous gift from Dr. Peter S. Heeger (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai). Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Mount Sinai.

2.2. Flow cytometry and sample preparation

For DC staining, cell suspensions were obtained after enzymatic digestion [(2mg/ml collagenase D (Roche), 50U/ml DNAse I (Invitrogen)]. Foxp3 staining was performed using Foxp3 staining kit (eBioscience) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were analyzed using an LSR Fortessa flow cytometer and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc). The following antibodies were used: anti-CD8α (53–6.7), anti-CD11c (N418), anti-Foxp3 (FJK16s), anti-CD25 (PC61.5), anti-PDCA1 (129c1) from eBioscience; anti-CD4 (GK1.5) from Biolegend; anti-CD172a (P84) from BD.

2.3. tDC sorting

DCs were enriched from total thymocytes using CD11c microbeads (Miltenyi). CD11c-enriched cells were stained with anti-CD11c, -PDCA1, -CD8α, -SIRPα and tDC subsets were sorted as pDCs (CD11clowPDCA1+) and cDCs (CD11chighPDCA1−) subsets based on SIRPα and CD8α expression.

2.4. In vitro thymocyte apoptosis assay

Thymocytes (2.5–5×105) from OTII mice were cultured in 96-well flat-bottomed plates in presence or absence of sorted tDC subsets as indicated (1 tDCs per 5 thymocytes) and with or without OVA323–339 10µg/ml. Samples were then incubated at 37°C for 24 h before analysis. Cells were stained with annexin-V and propidium iodide (PI) (BD). Absolute quantifications of live thymocytes were obtained from culture triplicate by acquiring each well for 1min on a cytometer.

2.5. In vitro Treg differentiation assay

Sorted (2×104) CD4+CD8−CD25−GFPFoxp3− or (103) CD4+CD8−CD25−GFPFoxp3+ thymocytes from GFPFoxp3 mice were co-cultured with sorted tDC subsets (1tDCs per 5 thymocytes) in RPMI 1640 supplemented with Glutamax, 10% fetal calf serum, 0.02 mmol/L 2β-mercaptoethanol, and antibiotics in 96 wells flat bottom plate in triplicates for 5 days. Treg cell generation (CD25+GFPFoxp3+) was assessed by staining for CD4, and CD25 and expression of GFPFoxp3 by flow cytometry.

2.6. Histopathology

Pieces of the indicated organs were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections were stained with H&E and images were acquired with an Axioplan 2IE fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss).

2.7. Autoantibodies

Serum autoantibodies were detected using HEp-2 cells fixed on glass slides (MBL BION) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and as described [19].

2.8. Statistics

All bar graphs represent mean+standard error of the mean (s.e.m) and all scatter plots show individual mice and the mean. Statistical significance was determined using one-way anova with Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test or Dunnett's Multiple Comparison Test as indicated in each figure legends (Graph Prism). P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

3. Results

3.1. Generation of double knockout mice depleted of mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs

We previously generated conditional knockout mice in which Traf6, a known regulator of mTEC development, was specifically deleted in TECs using FoxN1-Cre knock-in mice (Traf6ΔTEC mice) [14, 19]. Deletion of Traf6 in TECs led to a marked reduction in the numbers of mature mTECs and a 50% reduction in the numbers of tTregs [19]. Despite these defects and production of autoantibodies against most tissues, inflammatory infiltrates were primarily found in the liver of young Traf6ΔTEC mice. The hepatic inflammation was manifested as autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) that recapitulated the known histopathological and immunological parameters of human AIH [19]. The lack of overt autoimmunity in Traf6ΔTEC mice (despite the depletion of mTECs and reduction in tTregs) suggested that compensatory mechanisms might operate to suppress inflammation in these mice. Indeed, previous evidence supports functional cooperation among the different thymic APC populations relating to autoreactive T cell deletion and tTreg cell production [reviewed by [20]]. Migratory SIRPα+ cDCs were shown to regulate T cell deletion and were potent inducers of tTreg cell production [5, 6, 21] whereas plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) primarily regulate tolerance through T cell deletion [8]. mTECs were shown to directly delete CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [10, 12, 22] and consistent with our previous results to regulate the production of Tregs [12, 19, 23, 24]. CD8α+ cDCs were also shown to mediate T cell deletion [25], induce Treg cell production [12] and present mTEC-derived antigens [10, 12, 26] suggesting cooperative functionality between these APCs in the elimination of autoreactive T cells and/or Treg cell production. These observations raised the possibility that the resident CD8α+ cDCs in Traf6ΔTEC mice were able to compensate for the absence of mTECs in suppressing overt autoimmunity. On the other hand, mice depleted of CD8α+ cDCs also fail to develop organ-specific autoimmunity suggesting that mTECs may functionally compensate for T cell tolerance in their absence.

To examine whether resident CD8α+ cDCs in Traf6ΔTEC mice were able to compensate for the absence of mTECs in preventing overt autoimmunity and if CD8α+cDCs can contribute to autoimmunity development, we generated mice double deficient in Traf6 (in mTECs) and Batf3, a transcription factor essential for CD8α+ cDC development [18, 27]. Because it took extensive breeding to recover viable Batf3−/−/Traf6ΔTEC double knockout (dKO) mice, we also generated Batf3−/−→Traf6ΔTEC BM chimeras. Abolishment of Irf8 and Batf3 expression resulted in marked reduction of CD8α+ cDCs in single knockout Irf8−/−, Batf3−/−, and double knockout (dKO) mice (Fig. 1A–B and D) and Batf3−/−→WT and Batf3−/−→Traf6ΔTEC chimeras (Fig. 1C–D). In contrast, migratory SIRPα+ cDCs whose development is Irf8/Batf3 independent were not affected in the absence of mTECs and/or SIRPα−CD8α+ (Fig. 1A–D).

Figure 1.

Conventional CD8α+ DCs are depleted in the thymus of Irf8−/−/Traf6ΔTEC and Batf3−/−/Traf6ΔTEC dKO mice. (A–C) Representative examples of thymic cDCs (CD11chighPDCA1−) stained with anti-CD8α and -SIRPα mAb using total thymocyte suspensions from mice with indicated genotype. (D) Quantification of SIRPα+ and CD8α+ cDCs, expressed as percentages of thymic cDCs, in Irf8−/−/Traf6ΔTEC mice (left bar graph), Batf3−/−/Traf6ΔTEC (middle bar graph) and chimeric Batf3−/−→Traf6ΔTEC mice. Results are expressed as mean + s.e.m. (n>3 mice per group). Depletion of CD8α+ cDCs in Irf8−/−, Irf8−/−/Traf6ΔTEC, Batf3−/−, Batf3−/−/Traf6ΔTEC and Batf3−/−→Traf6ΔTEC chimeras was statistically significant compared to WT and Traf6ΔTEC mice using 1-way anova with Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test.

3.2. Combined depletion of mTECs and SIRPα−CD8α+ cDCs induces overt, organ-specific autoimmunity

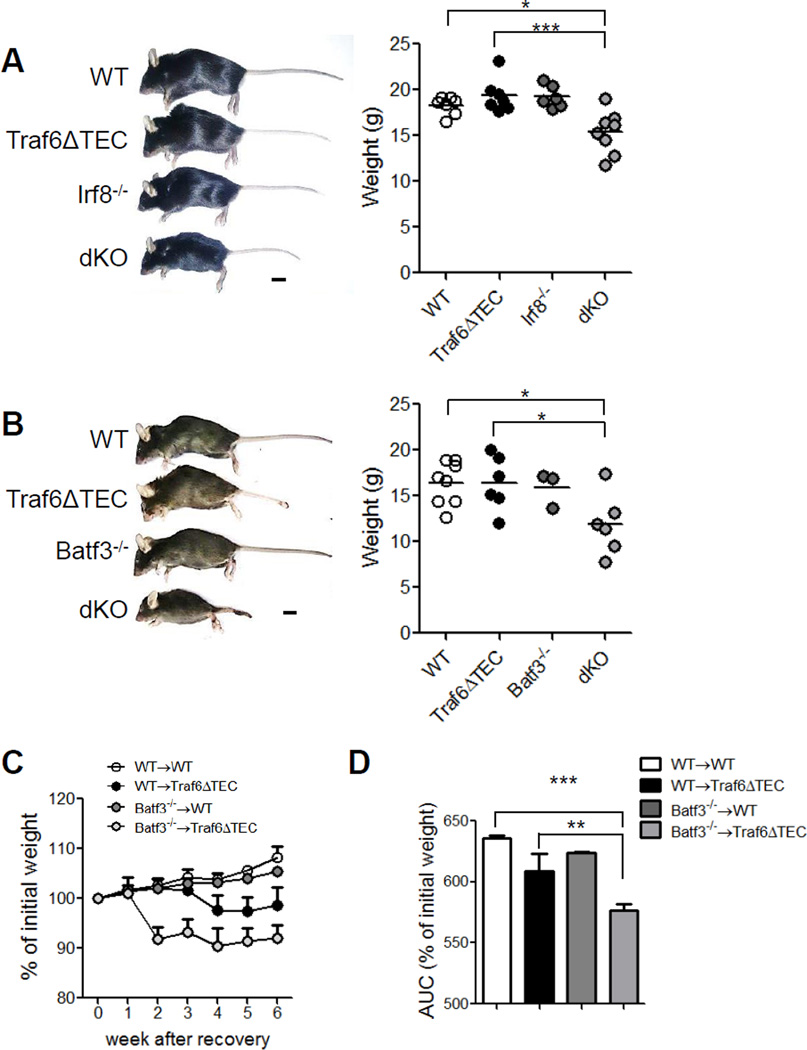

We next examined the combined effect of mTEC and CD8α+ cDC depletion on the development of peripheral autoimmune manifestations. Five to six-week-old dKO mice in the Irf8−/− and four to five-week old in the Batf3−/− backgrounds looked unhealthy and weighed significantly less than wild type (WT) and Traf6ΔTEC mice (Fig. 2A and B). Similarly, chimeric Batf3−/−→Traf6ΔTEC mice exhibited significant weight loss at 10 weeks post bone marrow (BM) transplantation when compared to the other chimeric groups (Fig. 2C and D). Contrary to Traf6ΔTEC mice which develop autoimmunity against the liver [19], H&E staining of different tissues revealed that 100% of dKO mice presented infiltrates in the liver, lung and kidney of increased incidence and severity compared to the Traf6ΔTEC or Irf8−/− mice (Fig. 3A and Table 1). While six-week-old Irf8−/− mice exhibited enlarged lymphoid organs as previously shown [27], there were no signs of inflammation in the tissues of these mice at the time of analysis, suggesting that the increased incidence and severity in the double-knockout animals were due to the combined defects of impaired tolerance induction by mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs in their thymus. Similar results were obtained with Batf3−/−→Traf6ΔTEC chimeric mice (Fig. 3B and Table 1) and Batf3−/−/Traf6ΔTEC dKO animals (data not shown and Table 1), which also exhibited inflammatory infiltrates in the liver, lung and kidney of increased incidence and severity compared to the Batf3−/−→WT chimeras and Traf6ΔTEC or Batf3−/− mice.

Figure 2. Lower weight in mice depleted of both mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs.

Photographs and weight quantification of (A) 5 to 6-week-old WT, Traf6ΔTEC, Irf8−/− and Irf8−/−/Traf6ΔTEC dKO mice and of (B) 4 to 5-week-old WT, Traf6ΔTEC, Batf3−/− and Batf3−/−/Traf6ΔTEC dKO mice. Scale bar 1cm. (C) Graph representing the percentage of initial weight over time starting four weeks after irradiation-transplantation of Batf3−/−/Traf6ΔTEC chimeras and (D) area under the curve of percentage of initial weight shown in (C). Results are shown as mean and individual mice (A–B), and mean + s.e.m (C–D). (n=3 Batf3−/− and >5 mice for all other groups of mice). Statistical significance was analyzed by 1-way anova with Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test.

Figure 3. Combined depletion of mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs leads to multi-organ autoimmunity.

Photographs of H&E-stained paraffin-embedded sections of indicated organs from (A) WT, Traf6ΔTEC, Irf8−/− and Irf8−/−/Traf6ΔTEC dKO and (B) from WT→WT, WT→Traf6ΔTEC, Batf3−/−→WT, Batf3−/−→Traf6ΔTEC chimeras. (C, D) Sera of WT, Traf6ΔTEC, Irf8−/− and Irf8−/−/Traf6ΔTEC dKO mice (C) and WT→WT, WT→Traf6ΔTEC, Batf3−/−→WT, Batf3−/−→Traf6ΔTEC chimeras (D) were used to stain HEp-2 cells and the presence of auto-antibodies (AutoAb) was revealed by anti–mouse IgG–FITC and fluorescence microscopy Quantification of AutoAb was performed on an arbitrary scale of 0–5, based on positive staining and fluorescence intensity. Scale bars 100µm. Results are shown as mean and individual mice . n>5 mice per group. Statistical significance was analyzed by 1-way anova with Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test.

Table 1.

Presence of inflammatory infiltrates in the indicated organs of mice deficient in mTECs and/or CD8α+ cDCs

| Mouse Genotype | Number of mice with infiltrates per indicated tissue | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | Lung | Kidney | Colon | |

| WT | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 |

| Traf6ΔTEC | 3/3 | 1/3 | 0/3 | 1/3 |

| Irf8−/− | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 |

| dKO | 6/6 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 1/6 |

| WT | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

| Traf6ΔTEC | 5/5 | 1/5 | 1/5 | 1/5 |

| Batf3−/− | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 |

| dKO | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 1/5 |

| WT→WT | 1/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 |

| WT→Traf6ΔTEC | 5/6 | 4/6 | 1/6 | 1/6 |

| Batf3−/−→WT | 1/6 | 1/6 | 0/6 | 2/6 |

| Batf3−/−→Traf6ΔTEC | 7/7 | 7/7 | 4/7 | 2/7 |

The increased inflammation in the tissues of mice with combined mTEC and CD8α+ cDC depletion was accompanied by increased production of autoantibodies (another manifestation of peripheral autoimmunity) in the sera of Irf8−/−/Traf6ΔTEC dKO (Fig. 3C) and chimeric Batf3−/− →Traf6ΔTEC mice (Fig. 3D). Due to the low number of Batf3−/−/Traf6ΔTEC dKO mice recovered and the variability of serum autoantibodies, serum autoantibody scores for Batf3−/−/Traf6ΔTEC dKO mice were not analyzed in these experiments. Together, these results reveal that CD8α+ cDCs in Traf6ΔTEC mice can to some extent but not completely compensate for mTECs to induce T cell tolerance and that, severe disturbances in the thymic APC compartment are required for overt autoimmunity development. In addition, these results suggest that mTECs and thymus-resident CD8α+ cDCs together make distinct contributions to T cell tolerance that cannot be compensated for by thymic migratory SIRPα+ cDCs and pDCs and that T cell specificities produced in the absence of thymus-resident CD8α+ cDCs can mediate the development of peripheral autoimmunity even in the absence of peripheral CD8α+ cDCs.

3.3. mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs cooperatively regulate T cell deletion whereas CD8α+ cDCs are dispensable for tTreg production

Previous evidence has shown functional cooperation among the different thymic APC populations relating to autoreactive T cell deletion [reviewed by [20]]. Deletion of autoreactive T cells can be mediated by mTECs in a cell autonomous fashion as well as by all thymic DC populations. We therefore examined how combined depletion of mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs affected the thymic T cell pool. Analysis of total thymocyte numbers revealed reduced overall thymic cellularity in Irf8−/−/Traf6ΔTEC and Batf3−/−/ Traf6ΔTEC mice consistent with the smaller body weight of these mice (Fig. 4A, left and middle panels). However, the frequency of CD4 and CD8 single positive (SP) cells was significantly increased compared to wild type controls, suggesting defective elimination of autoreactive T cells in the absence of both mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs (Fig. 4B, left and middle panels). The percentages of T cells were less affected in the Batf3−/−→cKO chimeric mice, possibly due to incomplete chimerism in these mice (Fig. 4A and B, right panels).

Figure 4. Increased frequency of SP Thymocytes in mice lacking mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs.

(A) Thymic cellularity and (B) percentage of CD4+CD8α− (CD4 SP) and CD4−CD8α+ (CD8 SP) thymocytes in WT, Traf6ΔTEC, Irf8−/− and Irf8−/−/Traf6ΔTEC dKO mice (left bar graph), WT, Traf6ΔTEC, Batf3−/− and Batf3−/−/Traf6ΔTEC dKO mice (middle bar graph) and in WT→WT, WT→Traf6ΔTEC, Batf3−/−→WT, Batf3−/−→Traf6ΔTEC chimeras (right bar graph). Results are expressed as mean + s.e.m of individual mice. n=3 Batf3−/− and >5 mice for all other groups of mice. Statistical significance was analyzed with a 1-way anova with Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test.

We previously showed that mTEC depletion associated with a 50% reduction in tTreg numbers in Traf6ΔTEC mice [19]. It has also been shown that self-antigens ectopically expressed by mTECs under the control of Aire, are transferred to thymic DCs which subsequently present these antigens and regulate production of tTregs [10, 12, 26]. Which DC subsets mediate the production of tTregs has been debated. While SIRPα+ migratory cDCs have been shown to exhibit robust Treg inducing activity, pDCs exhibit diminished ability to direct this function [6]. In the case of thymus-resident CD8α+ cDCs, a recent study by Perry et al. that employed T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire analysis suggested that these cells coordinate the production of Aire-dependent Tregs in the thymus [12]. In contrast, another study by Leventhal et al. using the same approach concluded that CD8α+ cDCs are dispensable for the production of an Aire-dependent, prostate-specific clonal population of T cells, as well as the polyclonal Treg cell repertoire and Batf3 deficiency had a negligible effect on Treg cell production [13].

In our system we found that depletion of CD8α+ in Irf8−/− and Batf3−/− mice had no effect in Treg cell frequency and deficiency in both mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs in Irf8−/−/Traf6ΔTEC or Batf3−/−/Traf6ΔTEC dKO or chimeric Batf3−/−→Traf6ΔTEC animals had no further significant effect in the frequency of Foxp3+ tTregs among CD4 T cells when compared to mTEC depletion alone (Fig. 5A). To further examine the role of CD8α+ cDCs on Treg production we examined the ability of these cells to induce mature Foxp3+CD25+ Tregs in vitro from conventional thymic CD4+Foxp3−CD25− T cells or CD4+ Foxp3+CD25− Treg precursors isolated from mice expressing GFP under the Foxp3 promoter. We found that among tDCs, SIRPα+ cDCs robustly induced Treg production from conventional or Treg precursor cells while the CD8α+ cDCs and pDCs displayed diminished capacity in inducing Tregs compared to the SIRPα+ subset under the same conditions (Fig. 5B). On the other hand, OVA-loaded SIRPα+, CD8α+ cDCs and pDCs were equally able to delete OTII thymocytes in vitro (Fig.5C). Together, these results suggest that while mTECs regulate production of tTregs, CD8a+ cDCs are dispensable for this process and they may instead control peripheral autoimmunity through deletional tolerance. Our results support the findings of Leventhal et al. [13] that CD8a+cDCs are dispensable for tTreg production and rather reveal that mTECs (and likely SIRPα+ cDCs) regulate this process.

Figure 5. CD8α+ cells are dispensable for thymic regulatory T cell production.

(A) Percentage of Foxp3+CD25+ tTreg among CD4 SP in WT, Traf6ΔTEC, Irf8−/− and Irf8−/−/Traf6ΔTEC dKO mice (left bar graph), WT, Traf6ΔTEC, Batf3−/− and Batf3−/−/Traf6ΔTEC dKO mice (middle bar graph) and in WT→WT, WT→Traf6ΔTEC, Batf3−/−→WT, Batf3−/− →Traf6ΔTEC chimeric mice (right bar graph). (B) Quantification of Treg (CD25+GFPFoxp3+) among CD4+ T cells five days after in vitro incubation of CD4+CD8−GFPFoxp3−CD25− -or CD4+CD8−GFPFoxp3+CD25− thymocytes with thymic DC subset. Quantification of viable cells by flow cytometry (AnnexinV−PI−) after 24 hours of in vitro incubation of total thymocytes from OTII mice with indicated thymic DC subsets with or without Ova323–339. Results are expressed as mean + s.e.m of individual mice (A) or of culture triplicates (B–C). n=3 Batf3−/− and >5 mice for all other groups of mice for (A), (B–C) are representative of two independent experiments with similar results. Statistical significance was analyzed with a 1-way anova with (A) Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test and (B–C) Dunnett's Multiple Comparison Test.

4. Discussion

The burden of inducing T cell tolerance is largely shared between thymic APCs primarily consisting of mTECs and tDCs. Here, we made several novel observations regarding the role of mTECs and tDCs in sustaining tolerance. First, mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs functionally cooperate in inducing central tolerance and controlling peripheral autoimmunity. Second, combined depletion of mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs results in overt autoimmunity due to impaired thymocyte deletion and mTEC-mediated production of Treg cells. Third, CD8α+ cDCs are dispensable for thymic Treg cell production. Fourth, severe depletion of at least two APC subsets are required for overt autoimmunity development and SIRPα+ cDCs and pDCs cannot compensate for mTEC and CD8α+ cDC function in tolerance induction.

Currently, a consensus has not yet been reached regarding the specific roles of mTECs and tDCs in tolerance induction because of limited peripheral autoimmune manifestations and differences in tTreg production, depending on the systems utilized [4, 14, 22, 28]. Recently, CD8α+ cDCs were shown to make qualitative contributions to the tTreg TCR repertoire [12]. Using transgenic mice expressing a fixed transgenic TCR-β and polyclonal TCRα chains together with retroviral expression of BM APC-derived Treg TCRs in thymocytes, Perry et al. found that SIRPα+ and CD8α+ cDCs play non-redundant roles in Treg selection as CD8α+ cDCs were required for selection of 50% of the Treg TCRs tested [12]. In contrast, using the same transgenic mice with fixed TCRβ/polyclonal TCRα chains Leventhal et al. showed that CD8α+ cDCs were dispensable for Treg cell production and that the thymic polyclonal TCR repertoire was not impacted by Batf3 deficiency [13].

Consistent with the results by Leventhal et al. here, we showed that Batf3−/− and Irf8−/− mice had normal mature tTregs and while depletion of mTECs associated with a 50% reduction in the frequency and numbers of Tregs [19], no additional effect on tTregs was observed with depletion of CD8α+ cDCs suggesting that these cells do not play a significant quantitative role in tTreg production. Together, these observations suggest that mTECs are responsible for the production of ~50% of tTreg cells, while the remaining DC subsets, SIRPα+ cDCs and/or pDCs, mediate the production of the remaining 50% of tTregs. Because the SIRPα+ DC subset is much more efficient in inducing tTreg cells in vitro compared to the other thymic DC subsets (shown here and ref [6]) and because Leventhal et al., showed that neither CD8α+ cDCs (using Batf3−/− mice) nor pDCs (using BDCA2-DTR mice) are important for tTreg cell TCR specificities [13], we believe that mTECs and SIRPα+ cDCs are responsible for the production of the great majority of tTregs. However, definitive proof for the role of SIRPα+ cDCs in tTreg cell production awaits the development of the appropriate experimental tools which are currently lacking.

In contrast to tTregs, we observed increased percentages of CD4+ or CD8+ single positive (SP) thymocytes in mice depleted of both mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs. This observation together with the absence of a further Treg cell defect in mTEC/CD8α+ DC-depleted mice compared to Traf6ΔTEC animals suggests that the development of severe autoimmunity in these mice is due to impaired deletional tolerance rather than impaired Treg production. While in the C57B/6 genetic background we found no difference in TCR-Vβ chain usage in Traf6ΔTEC, Irf8−/−, Batf3− /− mice and Batf3−/−/Traf6ΔTEC chimeras compared to WT controls (data not shown), in vitro results showed that CD8α+ DCs could efficiently delete OTII thymocytes to levels that were similar for all tDCs. However, CD8α+ cells were poor inducers of Tregs in vitro in comparison to SIRPα+ DCs. Thus, our results again suggest that CD8α+ cDCs do not play a major role in Treg production but that instead these cells regulate thymocyte selection through deletional tolerance.

It is of interest that, although CD8α+ cDCs can affect thymic selection, steady state Batf3−/− mice do not develop autoimmunity [12, 18]. It was previously shown that Irf8−/− mice display enlarged lymphoid organs and develop a myeloproliferative syndrome later in life [29]. However, at the time of analysis at 5–6 weeks of age, we found no inflammatory infiltrates in the different organs of these mice and Batf3−/− mice were also free of autoimmune manifestations as reported [12, 18]. It has been proposed that the absence of autoimmunity may be due to the fact that CD8α+ cDCs are required for both selection in the thymus and activation of the same TCR specificities in the periphery [12]. Our results showing severe autoimmunity in mTEC/CD8α+ cDC-depleted mice argue against this idea. Instead, our results demonstrate that ablation of more than one APC subset is required for development of severe peripheral autoimmunity. In addition, the conflicting reports by Birnberg et al. and Ohnmacht et al. concerning the role of DCs in autoimmunity support the idea that absolute or simultaneous depletion of more than one APC subset is required for overt autoimmunity [16, 17]. Thus, the lack of autoimmunity in the report by Birnberg et al., was attributed to the presence of pDCs and epidermal Langerhans cells (LCs) that were absent in the experimental system used by Ohnmacht et al. in which DC ablation correlated with development of fatal autoimmunity [16, 17]. Similarly, mouse models with mutations affecting signaling through the NFkB pathway such as the alymphoplasia (aly/aly) mice develop chronic autoimmunity resembling Sjorgren’s syndrome despite impaired mTEC development and reduced numbers of tDC subsets [30, 31], again suggesting that severe disruptions of more than one subsets of thymic APCs are required for development of autoimmunty. Consistent with this, it was shown that depletion of DCs down to 5% of physiologic levels can still efficiently induce tolerance [32]. Thus, while mTEC depletion and accompanied DC reduction in mTEC-depleted mice leads to chronic autoimmunity, depletion of at least another DC subset (in this case CD8α+ DCs) is required for development of multi-organ inflammation.

It is currently unclear whether mTECs in addition to CD8α+ cDCs can also functionally compensate for SIRPα+ cDCs and/or pDCs in preventing autoimmunity. Given the reported ability of mTECs to transfer self-antigens to CD8α+ cDCs [10, 11], it is possible that functional cooperation between thymic APCs is limited to distinct APC subsets. Consistent with this, the intact SIRPα+ cDC and pDC populations in mice depleted of both mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs could not rescue the development of overt autoimmunity. In the case of pDCs, while these cells have been shown to transport antigen from the periphery to the thymus to regulate negative selection [8] and have been implicated in the development of systemic autoimmunity [33, 34], to our knowledge their role in organ-specific autoimmunity has not been determined. Definitive evidence of whether mTECs may functionally overlap with SIRPα+ cDCs and/or pDCs and whether pDCs contribute to the development of autoimmunity in Traf6ΔTEC mice awaits the development of appropriate experimental tools.

5. Conclusion

In summary, this study provides new insight into the mechanisms that regulate antigen presentation in the thymus and the role of mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs in T cell tolerance as summarized in the graphical abstract. In the normal thymus, mTECs mediate deletion of CD4+ or CD8+ single positive (SP) cells, Treg cell production and transfer of antigens to CD8α+ cDCs for antigen presentation to T cells. In Traf6ΔTEC mice depletion of mTECs leads to impaired T cell deletion and Treg cell induction leading to development of chronic autoimmunity in the liver manifested as autoimmune hepatitis. Combined depletion of mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs leads to severely impaired T cell deletion and increased production of SP autoreactive T cells culminating in multi-organ autoimmunity. The antigen transfer from mTECs to CD8α+ cDCs and functional cooperation of these cell populations in the steady-state may represent an adaptation of the system for build-in redundancy in antigen presentation to safeguard against autoimmunity. If mTECs transfer antigen to several cDCs, themselves able to present antigen to several thousand of autoreactive T cells, we obtain a model, where a close collaboration between mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs triggers an exponential presentation of antigens to developing T cells in order to produce a tolerant TCR repertoire and avoid leakage of autoreactive T cells. Because we found that migratory SIRPα+ DCs and pDCs cannot compensate for the function of mTECs and CD8α+ cDCs, it is possible that thymus-resident mTECs/CD8α+ DCs and migratory SIRPα+ DCs/PDCs) differentially regulate tolerance to self- vs. peripheral antigens respectively. Better insight into how antigen presentation is orchestrated by different APC subsets in the thymus may lead to the development of novel strategies to treat thymic disorders associated with autoimmunity.

Highlights.

Depletion of mTECs and CD8α+ DCs leads to overt autoimmunity

mTECs and CD8α+ DCs cooperatively regulate thymocyte deletion

CD8α+ DCs do not play a quantitative role in thymic Treg production

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jeffery Haines for advice with statistical analysis. OH was recipient of the Mount Sinai Helmsley award. AJB and EGW were supported by a grant provided by The Levine Family Foundation. HX by grant RO1AI104688. The work and KA were supported by RO1 AI088106-01 and RO1 AI068963-01 grants and a grant by The Levine Family Foundation.

Abbreviations

- TEC

thymic epithelial cell

- mTEC

medullary thymic epithelial cell

- Traf6

TNF receptor associated factor 6

- Traf6ΔTEC

Traf6 deletion in FoxN1 expressing TEC

- cDC

conventional dendritic cell

- pDC

plasmacytoid dendritic cell

- dKO

double knock out

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Klein L, Hinterberger M, Wirnsberger G, Kyewski B. Antigen presentation in the thymus for positive selection and central tolerance induction. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:833–844. doi: 10.1038/nri2669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dresch C, Leverrier Y, Marvel J, Shortman K. Development of antigen cross-presentation capacity in dendritic cells. Trends in immunology. 2012;33:381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Proietto AI, van Dommelen S, Wu L. The impact of circulating dendritic cells on the development and differentiation of thymocytes. Immunology and cell biology. 2009;87:39–45. doi: 10.1038/icb.2008.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lei Y, Ripen AM, Ishimaru N, Ohigashi I, Nagasawa T, Jeker LT, et al. Aire-dependent production of XCL1 mediates medullary accumulation of thymic dendritic cells and contributes to regulatory T cell development. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011;208:383–394. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baba T, Nakamoto Y, Mukaida N. Crucial contribution of thymic Sirp alpha+ conventional dendritic cells to central tolerance against blood-borne antigens in a CCR2-dependent manner. J Immunol. 2009;183:3053–3063. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Proietto AI, van Dommelen S, Zhou P, Rizzitelli A, D'Amico A, Steptoe RJ, et al. Dendritic cells in the thymus contribute to T-regulatory cell induction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19869–19874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810268105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J, Park J, Foss D, Goldschneider I. Thymus-homing peripheral dendritic cells constitute two of the three major subsets of dendritic cells in the steady-state thymus. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2009;206:607–622. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hadeiba H, Lahl K, Edalati A, Oderup C, Habtezion A, Pachynski R, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells transport peripheral antigens to the thymus to promote central tolerance. Immunity. 2012;36:438–450. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein L, Kyewski B, Allen PM, Hogquist KA. Positive and negative selection of the T cell repertoire: what thymocytes see (and don't see) Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:377–391. doi: 10.1038/nri3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallegos AM, Bevan MJ. Central tolerance to tissue-specific antigens mediated by direct and indirect antigen presentation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2004;200:1039–1049. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hubert FX, Kinkel SA, Davey GM, Phipson B, Mueller SN, Liston A, et al. Aire regulates the transfer of antigen from mTECs to dendritic cells for induction of thymic tolerance. Blood. 2011;118:2462–2472. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-286393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perry JS, Lio CW, Kau AL, Nutsch K, Yang Z, Gordon JI, et al. Distinct contributions of Aire and antigen-presenting-cell subsets to the generation of self-tolerance in the thymus. Immunity. 2014;41:414–426. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leventhal DS, Gilmore DC, Berger JM, Nishi S, Lee V, Malchow S, et al. Dendritic Cells Coordinate the Development and Homeostasis of Organ-Specific Regulatory T Cells. Immunity. 2016;44:847–859. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexandropoulos K, Bonito AJ, Weinstein EG, Herbin O. Medullary Thymic Epithelial Cells and Central Tolerance in Autoimmune Hepatitis Development: Novel Perspective from a New Mouse Model. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:1980–2000. doi: 10.3390/ijms16011980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laan M, Peterson P. The many faces of aire in central tolerance. Frontiers in immunology. 2013;4:326. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohnmacht C, Pullner A, King SB, Drexler I, Meier S, Brocker T, et al. Constitutive ablation of dendritic cells breaks self-tolerance of CD4 T cells and results in spontaneous fatal autoimmunity. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2009;206:549–559. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birnberg T, Bar-On L, Sapoznikov A, Caton ML, Cervantes-Barragan L, Makia D, et al. Lack of conventional dendritic cells is compatible with normal development and T cell homeostasis, but causes myeloid proliferative syndrome. Immunity. 2008;29:986–997. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hildner K, Edelson BT, Purtha WE, Diamond M, Matsushita H, Kohyama M, et al. Batf3 deficiency reveals a critical role for CD8alpha+ dendritic cells in cytotoxic T cell immunity. Science. 2008;322:1097–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1164206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonito AJ, Aloman C, Fiel MI, Danzl NM, Cha S, Weinstein EG, et al. Medullary thymic epithelial cell depletion leads to autoimmune hepatitis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3510–3524. doi: 10.1172/JCI65414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopes N, Serge A, Ferrier P, Irla M. Thymic Crosstalk Coordinates Medulla Organization and T-Cell Tolerance Induction. Frontiers in immunology. 2015;6:365. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonasio R, Scimone ML, Schaerli P, Grabie N, Lichtman AH, von Andrian UH. Clonal deletion of thymocytes by circulating dendritic cells homing to the thymus. Nature immunology. 2006;7:1092–1100. doi: 10.1038/ni1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hinterberger M, Aichinger M, Prazeres da Costa O, Voehringer D, Hoffmann R, Klein L. Autonomous role of medullary thymic epithelial cells in central CD4(+) T cell tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:512–519. doi: 10.1038/ni.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cowan JE, Parnell SM, Nakamura K, Caamano JH, Lane PJ, Jenkinson EJ, et al. The thymic medulla is required for Foxp3+ regulatory but not conventional CD4+ thymocyte development. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2013;210:675–681. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aschenbrenner K, D'Cruz LM, Vollmann EH, Hinterberger M, Emmerich J, Swee LK, et al. Selection of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells specific for self antigen expressed and presented by Aire+ medullary thymic epithelial cells. Nature immunology. 2007;8:351–358. doi: 10.1038/ni1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Proietto AI, Lahoud MH, Wu L. Distinct functional capacities of mouse thymic and splenic dendritic cell populations. Immunology and cell biology. 2008;86:700–708. doi: 10.1038/icb.2008.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koble C, Kyewski B. The thymic medulla: a unique microenvironment for intercellular self-antigen transfer. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2009;206:1505–1513. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schiavoni G, Mattei F, Sestili P, Borghi P, Venditti M, Morse HC., 3rd ICSBP is essential for the development of mouse type I interferon-producing cells and for the generation and activation of CD8alpha(+) dendritic cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2002;196:1415–1425. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramsey C, Winqvist O, Puhakka L, Halonen M, Moro A, Kampe O, et al. Aire deficient mice develop multiple features of APECED phenotype and show altered immune response. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:397–409. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.4.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holtschke T, Lohler J, Kanno Y, Fehr T, Giese N, Rosenbauer F, et al. Immunodeficiency and chronic myelogenous leukemia-like syndrome in mice with a targeted mutation of the ICSBP gene. Cell. 1996;87:307–317. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81348-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsubata R, Tsubata T, Hiai H, Shinkura R, Matsumura R, Sumida T, et al. Autoimmune disease of exocrine organs in immunodeficient alymphoplasia mice: a spontaneous model for Sjogren's syndrome. European journal of immunology. 1996;26:2742–2748. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mouri Y, Nishijima H, Kawano H, Hirota F, Sakaguchi N, Morimoto J, et al. NF-kappaB-inducing kinase in thymic stroma establishes central tolerance by orchestrating cross-talk with not only thymocytes but also dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2014;193:4356–4367. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klein L, Hinterberger M, von Rohrscheidt J, Aichinger M. Autonomous versus dendritic cell-dependent contributions of medullary thymic epithelial cells to central tolerance. Trends in immunology. 2011;32:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rowland SL, Riggs JM, Gilfillan S, Bugatti M, Vermi W, Kolbeck R, et al. Early, transient depletion of plasmacytoid dendritic cells ameliorates autoimmunity in a lupus model. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2014;211:1977–1991. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Isaksson M, Ardesjo B, Ronnblom L, Kampe O, Lassmann H, Eloranta ML, et al. Plasmacytoid DC promote priming of autoimmune Th17 cells and EAE. European journal of immunology. 2009;39:2925–2935. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]