Abstract

Introduction

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) after coronary stenting prolongs survival by preventing both in-stent thrombosis and other cardiovascular atherothrombotic events. Patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) typically have a heavy burden of unrevascularized coronary artery disease and also stand to benefit from increased atherothrombotic protection with DAPT. The potential benefit of DAPT compared to aspirin alone in patients with PAD is not well described.

Methods

We identified all patients undergoing an initial elective lower extremity revascularization (bypass or endovascular) from 2003 to 2016 in the Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) registry discharged on aspirin or aspirin plus a thenopyradine anti-platelet agent (dual anti-platelet therapy (DAPT)). We first estimated models predicting the likelihood of receiving DAPT and then used inverse probability weighting to account for baseline differences in the likelihood to receive DAPT and compared late survival. For sensitivity analysis we also performed Cox proportion hazard modeling on the unweighted cohorts and generated adjusted survival curves.

Results

We identified 57,041 patients undergoing lower extremity revascularization (28% bypass). Of 15,985 bypasses (69% for critical limb ischemia (CLI)) 38% were discharged on DAPT. Of 41,056 endovascular interventions (39% for CLI) 69% were discharged on DAPT. Analyses using inverse probability weighting demonstrated small survival benefits to DAPT at one-year for bypass (93% vs. 92%, P = .001) and endovascular interventions (93% vs. 92%, P = .005) that was sustained through five-years of follow-up (bypass: 80% vs. 78%, P = .004; Endovascular: 76% vs. 73%, P = .002). When stratified by severity of PAD, DAPT had a survival benefit for patients with CLI undergoing bypass (five-year: 70% vs. 66%, P = .04) and endovascular intervention (five-year: 71% vs. 67%, P = .01) but not for patients with claudication (bypass: 89% vs. 88%, P = .36; endovascular: 87% vs. 85%, P = .46). The protective effect of DAPT was similar when using Cox Proportional hazard models after bypass (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.72 – 0.90) and endovascular intervention (HR 0.89, 0.83 – 0.95).

Conclusion

Dual antiplatelet therapy at time of discharge was associated with prolonged survival for patients with CLI undergoing lower extremity revascularization but not for those with claudication. Further research is needed to quantify the risks associated with DAPT and to identify subgroups at increased risk of thrombotic and bleeding complications in order to guide medical management of patients with PAD.

Introduction

Atherothrombotic disorders of the cerebrovascular, coronary, and peripheral arterial circulation, affect nearly 20–30% of those older than 70 years of age and are among the leading causes of death and disability in the world.[1–3] Individuals with peripheral artery disease (PAD), referring to arterial vascular disease of the extremities, have the greatest risk of experiencing cardiovascular death and myocardial infarction when compared to those with coronary artery disease or cerebrovascular disease alone.[4, 5] PAD usually signals more systemic atherosclerotic disease and often goes undiagnosed and undertreated, which is thought to be a major reason for why these patients have been found to be at increased risk for major adverse cardiovascular events and mortality.[5–8]

One of the major goals of antiplatelet therapy is for prevention, both primary and secondary, of acute thrombotic events. Despite the increased local and systemic cardiovascular risk in PAD patients, the literature on the most effective antiplatelet regimen and its recommended duration are lacking, especially compared to studies primarily focusing on coronary artery disease.[9–15] The major consensus guidelines for PAD suggest using mono antiplatelet therapy in PAD but state that the data either for or against the use of DAPT in this population are too limited to make strong recommendations.[1, 9, 10, 16] There has been an attempt to update the international TASC guidelines but disagreement among the societies has delayed a universally accepted TASC III document.[17] At a cellular level there is an argument for potential benefit of DAPT in PAD, with evidence that points towards a synergistic effect of two antiplatelet agents for preventing in-stent thrombosis, similar to stenting for CAD.[18, 19] The DAPT trial, however, reported a benefit to DAPT in coronary vessels outside of the initially stented coronary lesion, suggesting the benefit to DAPT extends beyond just prevention of in-stent thrombosis.[15] These data raise the question of whether patients with PAD would benefit from DAPT, similar to those who have been treated with a coronary stent, given the high atherosclerotic burden of this population. An early single-center observational study in a PAD population showed a reduction in MACE and mortality associated with DAPT, and subgroup analysis from the CHARISMA trial, showed a similar reduction in MI associated with DAPT, suggesting this might be true.[20, 21]

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to evaluate the effect of DAPT at time of discharge, on survival following lower extremity revascularization across the Vascular Quality Initiative.

Methods

Dataset

We performed a retrospective analysis of data collected prospectively by the Vascular Quality Initiative (SVS-VQI) from 2003–2016. The VQI is a national clinical registry, set up as a collaboration among regional quality groups in an effort to improve patient care through the collection of clinical data, and includes 17 regions and close to 370 participating hospitals with well over 1300 physicians. More information about the SVS-VQI can be found at www.vascularqualityinitiative.org/. The VQI routinely performs annual audits comparing registry data to hospital claims to ensure >99% capture rate for all tracked procedures. Furthermore, all mortality data is supplemented by semi-annual matching of registry data with the Social Security Death Index. This study was approved, with informed consent waived, by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Definitions and variables

103,101 lower extremity revascularizations, both bypass and endovascular, were identified in the VQI form 2003–2016. As many VQI patients have multiple procedures, we selected only a patient’s first procedure, bypass or endovascular intervention, in the VQI, which excluded 26,868 subsequent procedures. We chose first procedure versus most recent in order to maximize follow-up time and avoid the confounding on survival related to prior procedures. We then excluded all emergent cases (n = 2630) and any patient on no antiplatelet medications (n = 6763) or mono- P2Y12 antagonist (n= 7871) at discharge, or missing this information (n = 623). Patients missing symptom status (n = 1245), or who died in-hospital (n = 60) were further excluded. This left 57,041 lower extremity revascularizations of which 28% were bypass.

Medications at time of discharge were used to group patients into either mono-antiplatelet or dual-antiplatelet (DAPT) treatment cohorts. Our mono-antiplatelet group was aspirin, any dose. Our DAPT group was aspirin combined with any P2Y12 antagonist, which included Clopidogrel, Prasugrel, Ticlopidine, Ticagrelor, or other antagonists not specified. DAPT was defined as discharge on both groups of antiplatelet medication. Patients who were reported as not taking a P2Y12 antagonist for either non-compliance or medical reasons, such as allergy, were included in the mono-therapy if they were still on Aspirin. We could not further assess adherence outside of what was reported in the VQI and no serological testing was done to evaluate potential medication resistance. We chose to study only Aspirin as our mono-antiplatelet group as it makes this study more readily comparable to CHARISMA and to Armstrong et al., and is the most common antiplatelet agent used in patients with PAD.[20, 21]

Survival days were calculated from date of procedure to the time of death or the end of the follow-up period (January, 2016). The VQI collects over 100 clinical and demographic variables for each patient. Full details are available elsewhere.[22] Definitions for comorbidities and details are available on-line at www.vascularqualityinitiative.org. We defined the presence of significant diabetes as those patients identified with diabetes that were taking a medication, either an oral agent or insulin. Renal dysfunction was classified as either preoperative dialysis or chronic renal insufficiency as defined by an elevated baseline creatinine of >1.78mg/dl. Patients without documentation of any stress test were counted as part of the normal group. Anticoagulation medications, which included, warfarin, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or other, were consolidated into a binary (yes/no) variable for both preoperative and discharge medications. The preoperative mono-antiplatelet group included Aspirin or any P2Y12 antagonist.

Statistical analysis

All data within the VQI has been de-identified and so all analysis was conducted in a blinded manner, in terms of patient, hospital, and surgeon identity. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages. Univariate differences between cohorts were assessed using χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables, where appropriate.

In order to analyze proportions of medication therapy at one-year follow-up, we reported antiplatelet, anticoagulation, and statin use at one-year. For this part of the analysis only patients eligible for one-year follow-up, meaning the procedure took place more than 8 months before date of data extraction, were analyzed using an intent to treat approach.

In order to adjust for preoperative differences between our DAPT and Aspirin only cohorts we first estimated a logistic regression model predicting the likelihood of being discharged on DAPT (the propensity score), for patients undergoing bypass and those undergoing endovascular intervention separately, that were then used to weight each cohort using inverse probability weighting to create analytic cohorts that are balanced (i.e., have the same distribution) with respect to propensity to receive DAPT.[23] Following estimation of the propensity score, we compared the pre- and post-weighting distributions of the component predictors to determine whether balance had been achieved on the individual predictors. Variables used in the regression to generate the propensity scores included age (continuous, in years), sex, smoking (never, previous, current), coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, increased baseline Creatinine but not on dialysis (>1.78mg/dl), dialysis dependent, history of abnormal stress test, documented prior vascular procedure (lower extremity open bypass or endovascular procedure), history of CEA/CAS, prior coronary revascularization (CABG or percutaneous coronary intervention), urgency (elective or urgent-defined as non-elective surgery that occurs from 12–72 hours after admission), preoperative antiplatelet medications (mono-, dual-, or none), preoperative anticoagulation, and preoperative statin. We found that the standardized difference in the distribution of each predictor between the DAPT and non-DAPT group was substantially smaller than it was prior to weighting. Furthermore, the post-weighting absolute differences were all less than 0.1, the commonly-used threshold for assessing whether adequate balance had been achieved. Using propensity score weighting thus succeeded in creating study cohorts that are balanced on the multiple observed characteristics available in the VQI, while keeping all patients in the analysis, which would not have been possible under commonly-used matching methods. The weighted cohorts were also compared by baseline characteristics using χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables, although the tests of statistical significance are less important than the standardized differences themselves. We then used propensity score weighted unadjusted Cox proportional hazard models to compare the risk of mortality among the DAPT and Aspirin groups. The proportional hazard assumption is reasonable for comparisons between the two treatment groups as their risk profiles track closely over time. To complement the estimated hazard-ratios we converted the estimated Cox proportional hazards model and baseline hazard function into a series of fixed-time event probabilities. While the estimated hazard-ratios generated under the Cox model provide a parsimonious summary of the relative effectiveness of the different treatment options, the estimated survival probabilities report the treatment effect in terms that are easier to interpret.

As a sensitivity analysis we used Cox proportional hazards models in the unweighted cohort to again adjust for preoperative differences and also assess the influence of additional preoperative and discharge characteristics. This method also allowed us to produce adjusted survival curves.

However, in performing these analyses we recognize that conditioning the post-treatment predictors may introduce new biases (e.g., removing part of the treatment effect or introducing endogenous selection bias by conditioning on variables that are effects of treatment). For all Cox survival curves the standard error remained < .10 on reported data. All tests were two-tailed with P-values < .05 considered significant. For this analysis both SPSS Version 22.0 (IDM Inc., Chicago, IL) and SAS, version 9.3, Copyright, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA were used for all analysis.

Results

Patient population

Of the 70,974 lower extremity revascularizations, 19,229 were for patients undergoing bypass with 9967 discharged on Aspirin mono-therapy, 6018 discharged on DAPT, 1323 discharged on non-Aspirin mono-antiplatelet therapy, and 1921 on no antiplatelet agents. There were 51,745 patients undergoing endovascular intervention with 12,559 discharged on Aspirin alone, 28,497 on DAPT, 6347 on non-Aspirin mono-therapy, and 4342 on no antiplatelet agents. After excluding patients on non-Aspirin mono-therapy and no antiplatelet agents 57,041 lower extremity revascularizations remained.

Among patients selected to undergo lower extremity bypass, 38% were discharged on DAPT compared to mono therapy with Aspirin. Those discharged on DAPT were slightly younger and more likely to be female, current smokers, have coronary artery disease (CAD), congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), prior abnormal stress test, and be undergoing an urgent operation (Table IA). Those discharged on DAPT were also more likely to have undergone a prior carotid, coronary, and peripheral revascularization. Those discharged on DAPT after bypass were more likely to have been on DAPT preoperatively (47% vs. 5%, P < .001) and less likely to have been on preoperative anticoagulation (8% vs. 18%, P < .001)(Table IIA). Patients on DAPT at discharge were also more likely to be discharged on a statin (81%, vs. 78%, P < .001) and less likely to be discharged on anticoagulation (11% vs. 28%, P < .001).

Table I.

| A. Patient Characteristics in unweighted and weighted cohorts for patients undergoing Bypass | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bypass Unweighted data |

Bypass Weighted data* |

|||||||||

| Mono | DAPT | P-value | Mono | DAPT | P-value | |||||

| N | 9967 | 6018 | 9867 | 5948 | ||||||

| Age (mean ±SD) | 67.3 | 11.4 | 66.6 | 10.6 | <.001 | 66.9 | .14 | 67.0 | .19 | .66 |

| Female % | 29.7% | (2956) | 32.4% | (1951) | <.001 | 30.9% | (6818) | 30.5% | (4134) | .69 |

| White race % | 85.0% | (8475) | 80.7% | (4851) | <.001 | 81.2% | (4400) | 81.5% | (4421) | .61 |

| Smoking | .02 | .91 | ||||||||

| Never | 17.2% | (1711) | 15.5% | (932) | 16.6% | (1642) | 16.7% | (995) | ||

| Former | 42.6% | (4240) | 43.0% | (2584) | 42.5% | (4193) | 42.9% | (2549) | ||

| Current | 40.2% | (4006) | 41.5% | (2494) | 40.9% | (4032) | 40.4% | (2404) | ||

| HTN | 85.6% | (8527) | 90.0% | (5416) | <.001 | 86.5% | (8531) | 88.4% | (5257) | .01 |

| Diabetes | 41.6% | (4144) | 46.5% | (2795) | <.001 | 43.4% | (4282) | 43.6% | (2596) | .82 |

| Any Coronary artery disease | 28.3% | (2813) | 36.6% | (2198) | <.001 | 31.7% | (3127) | 31.5% | (1876) | .87 |

| Any CHF | 14.6% | (1457) | 16.5% | (994) | .001 | 15.7% | (1545) | 15.3% | (910) | .64 |

| Any COPD | 23.9% | (2382) | 26.1% | (1571) | .002 | 24.1% | (2380) | 25.8% | (1534) | .06 |

| Elevated baseline Creatinine (> | 6.2% | (575) | 6.3% | (351) | .86 | |||||

| 1.78mg/dl) | 6.5% | (611) | 7.0% | (397) | .23 | |||||

| On dialysis | 4.9% | (493) | 5.3% | (317) | .36 | 4.9% | (486) | 5.1% | (304) | .69 |

| Prior abnormal stress test | 8.8% | (870) | 11.3% | (677) | <.001 | 9.8% | (968) | 9.8% | (581) | .95 |

| Elective (vs. urgent) | 79.0% | (7873) | 81.7% | (4914) | <.001 | 78.9% | (7785) | 79.1% | (4709) | .77 |

| Symptoms | <.001 | .97 | ||||||||

| Asymptomatic | 6.0% | (596) | 3.4% | (205) | 4.7% | (465) | 4.6% | (275) | ||

| Claudication | 26.1% | (2603) | 28.1% | (1689) | 26.4% | (2602) | 26.5% | (1579) | ||

| Rest pain | 21.7% | (2161) | 23.2% | (1395) | 22.8% | (2246) | 22.2% | (1321) | ||

| Tissue Loss | 37.0% | (3686) | 35.5% | (2134) | 36.4% | (3589) | 36.9% | (2193) | ||

| ALI | 9.2% | (921) | 9.9% | (595) | 9.8% | (965) | 9.8% | (581) | ||

| Prior Procedures | ||||||||||

| PVI or bypass | 40.9% | (4070) | 58.2% | (3503) | <.001 | 48.2% | (4758) | 48.2% | (2865) | .96 |

| CEA or CAS | 8.2% | (814) | 12.1% | (728) | <.001 | 9.9% | (975) | 9.7% | (576) | .75 |

| Major Amputation | 4.4% | (438) | 5.0% | (298) | .10 | 4.8% | (474) | 4.7% | (280) | .83 |

| CABG or PCI | 29.4% | (2925) | 44.4% | (2662) | <.001 | 34.4% | (3399) | 34.4% | (2047) | .97 |

| B. Patient Characteristics in unweighted and weighted cohorts for patients undergoing Endovascular Intervention | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endovascular Unweighted data |

Endovascular Weighted Data* |

|||||||||

| Mono | DAPT | P- value |

Mono | DAPT | P-value | |||||

| N | 12559 | 28497 | 12440 | 28244 | ||||||

| Age (mean ±SD) | 69.1 | 11.5 | 67.6 | 11 | <.001 | 67.8 | .16 | 68.1 | .07 | .07 |

| Female % | 38.8% | (4878) | 39.8% | (11334) | .08 | 40.1% | (7431) | 39.6% | (17054) | .42 |

| White race % | 82.1% | (10301) | 81.3% | (23158) | .06 | 82.1% | (9832) | 81.9% | (9806) | .66 |

| Smoking | <.001 | .38 | ||||||||

| Never | 22.5% | (2822) | 19.5% | (5542) | 20.20% | (2515) | 20.4% | (5772) | ||

| Former | 43.4% | (5446) | 42.1% | (11973) | 41.60% | (5178) | 42.5% | (11993) | ||

| Current | 34.0% | (4266) | 38.4% | (10937) | 38.20% | (4747) | 37.1% | (10480) | ||

| HTN | 87.9% | (11033) | 88.1% | (25102) | .44 | 88.50% | (11012) | 87.9% | (24815) | .19 |

| Diabetes | 44.2% | (5549) | 45.5% | (12942) | .02 | 44.80% | (5577) | 45.2% | (12754) | .69 |

| Any Coronary artery disease | 28.0% | (3517) | 32.4% | (9230) | <.001 | 30.50% | (3792) | 31.1% | (8772) | .46 |

| Any CHF | 17.9% | (2243) | 16.0% | (4570) | <.001 | 16.40% | (2035) | 16.6% | (4689) | .68 |

| Any COPD | 24.5% | (3072) | 24.0% | (6826) | .27 | 25.10% | (3118) | 23.7% | (6700) | .05 |

|

Elevated baseline creatinine (>1.78mg/dl) |

7.7% | (889) | 6.3% | (1664) | <.001 | 6.00% | (697) | 6.6% | (1737) | .08 |

| On dialysis | 7.4% | (929) | 5.9% | (1673) | <.001 | 5.90% | (735) | 6.4% | (1794) | .18 |

| Prior abnormal stress test | 5.1% | (637) | 6.3% | (1790) | <.001 | 6.20% | (768) | 6.0% | (1684) | .62 |

| Elective (vs. urgent) | 85.0% | (10671) | 87.6% | (24958) | <.001 | 84.60% | (10524) | 86.6% | (24452) | <.001 |

| Symptoms | <.001 | .81 | ||||||||

| Asymptomatic | 6.9% | (863) | 4.5% | (1292) | 4.90% | (605) | 5.2% | (1466) | ||

| Claudication | 44.2% | (5547) | 52.1% | (14856) | 49.40% | (6146) | 49.7% | (14035) | ||

| Rest pain | 11.2% | (1412) | 12.2% | (3478) | 12.30% | (1527) | 11.9% | (3367) | ||

| Tissue Loss | 30.6% | (3846) | 25.5% | (7269) | 27.20% | (3382) | 27.1% | (7648) | ||

| ALI | 7.1% | (891) | 5.6% | (1602) | 6.30% | (780) | 6.1% | (1729) | ||

| Prior Procedures | ||||||||||

| PVI or bypass | 31.2% | (3916) | 35.8% | (10198) | <.001 | 32.80% | (4079) | 34.4% | (9703) | .04 5 |

| CEA or CAS | 8.0% | (1006) | 9.7% | (2762) | <.001 | 8.10% | (1007) | 9.1% | (2576) | .03 |

| Major Amputation | 4.2% | (524) | 3.6% | (1037) | .01 | 3.40% | (419) | 3.8% | (1069) | .11 |

| CABG or PCI | 33.2% | (4159) | 40.6% | (11564) | <.001 | 38.00% | (4728) | 38.3% | (10822) | .70 |

Defined as 1/(prob(k)) for treatment k

Table II.

| A. Perioperative and Discharge Medications in unweighted and weighted cohorts for patients undergoing Bypass | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bypass Unweighted data |

Bypass Weighted data |

|||||||||

| Mono | DAPT | P-value | Mono | DAPT | P-value | |||||

| N | 9967 | 6018 | 9867 | 5948 | ||||||

| Perioperative Medications | ||||||||||

| Antiplatelet regimen | <.001 | .84 | ||||||||

| Mono | 75.3% | (7496) | 39.8% | (2390) | 61.5% | (6065) | 62.3% | (3690) | ||

| DAPT | 5.2% | (515) | 47.3% | (2844) | 21.6% | (2131) | 21.2% | (1258) | ||

| None | 19.6% | (1948) | 12.9% | (778) | 16.9% | (1671) | 16.8% | (1001) | ||

| Anticoagulation [33%] | 18.0% | (1116) | 7.8% | (356) | <.001 | 13.5% | (901) | 13.5% | (542) | .99 |

| Statin | 67.8% | (6753) | 74.6% | (4487) | <.001 | 70.3% | (6933) | 70.6% | (4201) | .71 |

| Medications at Discharge | ||||||||||

| Anticoagulation | 27.5% | (2777) | 10.5% | (633) | <.001 | 29.1% | (2865) | 11.8% | (702) | <.001 |

| Statin | 77.6% | (7270) | 80.9% | (4802) | <.001 | 79.3% | (7443) | 78.7% | (4580) | .51 |

| B. Perioperative and Discharge Medications in unweighted and weighted cohorts for patients undergoing Endovascular Intervention | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endovascular Unweighted data |

Endovascular Weighted data |

|||||||||

| Mono | DAPT | P-value | Mono | DAPT | P-value | |||||

| N | 12557 | 28496 | 12440 | 28244 | ||||||

| Perioperative Medications | ||||||||||

| Antiplatelet regimen | <.001 | .37 | ||||||||

| Mono | 79.4% | (9964) | 45.1% | (12846) | 54.8% | (6821) | 55.6% | (15711) | ||

| DAPT | 5.2% | (656) | 43.0% | (12256) | 32.5% | (4046) | 31.5% | (8889) | ||

| None | 15.4% | (1926) | 11.8% | (3372) | 12.6% | (1573) | 12.9% | (3645) | ||

| Anticoagulation | 16.9% | (2122) | 6.0% | (1706) | <.001 | 9.0% | (1122) | 9.3% | (2616) | .48 |

| Statin | 67.0% | (8418) | 71.5% | (20366) | <.001 | 70.5% | (8774) | 70.2% | (19818) | .59 |

| Medications at Discharge | ||||||||||

| Anticoagulation | 21.5% | (2699) | 6.7% | (1920) | <.001 | 16.6% | (2070) | 9.0% | (2528) | <.001 |

| Statin | 71.4% | (8965) | 76.9% | (21913) | <.001 | 74.1% | (9217) | 76.1% | (21478) | .003 |

[] reports % missing data, reported for any variable with > 5% missing

For patients selected to undergo endovascular intervention 69% were discharged on DAPT compared to mono Aspirin therapy. This proportion being discharged on DAPT increased from 65% at the start of the study to 71% in 2015. Those discharged on DAPT were younger, more likely to be current smokers, have diabetes, have CAD, and have a history of a prior abnormal stress test (Table IB). However, those on DAPT at discharge were less likely to have CHF, be dialysis dependent, and have an urgent intervention . Patients discharged on DAPT had more prior carotid, coronary, and peripheral revascularizations but fewer major amputations. Preoperative, more patients in the DAPT group were on a statin (72% vs. 67%, P <. 001) and DAPT (43% vs. 5%, P < .001) but fewer were on anticoagulation (6% vs. 17%, P < .001)(Table IIB). At discharge DAPT patients were more likely on a statin (775 vs. 71%, P < .001) but less likely to be on anticoagulation (7% vs. 22%, P < .001).

There was wide variation in prescribing patterns across the 17 VQI regions with more patients discharged on DAPT after endovascular interventions (regional range for CLI: 42–60%; Claudication: 45%-72%) than bypass (CLI: range 18 – 46%; Claudication: 17 – 48%).

Medications at one-year were often missing, with only 36% – 47% of eligible patients having medication information reported in follow-up (Table III). Of the patients with follow-up data, after bypass, 76% of the Mono group remained on mono-therapy with 12% escalating to DAPT and 13% on no antiplatelet at follow-up. Of the 13% not on antiplatelet medications at follow-up 40% were on anticoagulation. In the DAPT group 58% remained on DAPT at follow-up with 34% de-escalating to mono-therapy and 7% to no antiplatelet therapy (with 31% of this population on anticoagulation). Of the patients with follow-up in the endovascular cohort, 69% of the Mono group remained on mono-antiplatelet therapy, 19% escalated to DAPT and 12% de-escalated to no antiplatelet therapy (with 34% of this population on anticoagulation). In the DAPT group 58% remained on DAPT at one-year with 36% de-escalating to mono-antiplatelet therapy and 6% to no antiplatelet medications (10% of those on anticoagulation). Among the patients with follow-up data at one year, the rate of non-compliance in the bypass group discharged on DAPT was 1.5% and in the endovascular group was 1.1%. A further 4.6% in the bypass DAPT group and 4.1% in the endovascular DAPT group de-escalated their antiplatelet regimen due to side effects. After IPW there were no remaining differences after bypass and few after endovascular intervention, which included a slightly higher rate of elective procedures (87% vs. 85%, P < .001), and more patients with prior bypass or endovascular intervention (34% vs. 33%, P = .045) and prior carotid revascularization (9% vs. 8%, P = .03) in the DAPT group (Table IB).

Table III.

Medications at One-year in unweighted cohorts for patients undergoing Bypass and Endovascular Intervention

| Bypass | Endovascular | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mono | DAPT | P-value | Mono | DAPT | P-value | |||||

| Eligible for one-year follow-up (N) | 9051 | 5269 | 10969 | 24114 | ||||||

| Antiplatelet Regimen | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||||

| Mono | 75.7% | (4069) | 34.3% | (1000) | 69.3% | (3353) | 35.9% | (4076) | ||

| DAPT | 11.6% | (623) | 58.4% | (1704) | 19.0% | (920) | 58.2% | (6616) | ||

| No Antiplatelet | 12.7% | (683) | 7.3% | (213) | 11.7% | (565) | 5.9% | (673) | ||

| On Anticoagulation | 40.0% | (186) | 31.1% | (56) | .04 | 33.9% | (172) | 24.5% | (153) | <.001 |

| Anticoagulation | 27.3% | (956) | 14.3% | (335) | <.001 | 21.1% | (898) | 9.8% | (992) | <.001 |

| Statin | 73.7% | (3982) | 77.5% | (2269) | <.001 | 81.8% | (3614) | 77.3% | (8824) | <.001 |

Proportion missing follow-up data at one-year was 36% for bypass and 47% for endovascular intervention

Survival Analysis

Table IV describes the estimated survival rate at one-year through five-years following lower extremity revascularization. The weighted Cox model hazard ratios associated with DAPT that were used to generate survival rates were as follows for each intervention group: Bypass-claudication HR 0.91 (95% CI 0.73 – 1.1, P = .40), Bypass-CLI HR 0.86 (0.78 – 0.95, P = .003), Endovascular-claudication HR 0.93 (0.82 – 1.1, P = .25), and Endovascular-CLI HR 0.89 (0.82 – 0.96, P = .004). For both bypass and endovascular interventions the hazard-ratios translated to a survival benefit at one-year (Bypass: 93% vs. 92%, P = .001; Endovascular: 93% vs. 92%, P = .005) that persisted through five-years (Bypass: 80% vs. 78%, P = .004; Endovascular: 76% vs. 73%, P = .002). Patients with CLI had a greater sustained survival benefit after both bypass (one-year: 88% vs. 87%, P = .01; five-year: 70% vs. 66%, P = .04) and endovascular intervention (one-year: 91% vs. 90%, P = .02; five-year: 71% vs. 67%, P = .01). However, there was no clear survival benefit to DAPT for patients with claudication undergoing either bypass or endovascular intervention.

Table IV.

Survival by Year in Weighted Cohort

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASA | DAPT | P-value | ASA | DAPT | P-value | ASA | DAPT | P-value | ASA | DAPT | P-value | ASA | DAPT | P-value | |

| Bypass | 92.3% | 93.1% | .001 | 88.1% | 89.3% | <.001 | 84.9% | 86.4% | <.001 | 81.1% | 83.0% | .001 | 78.1% | 80.3% | .004 |

| Claudication | 97.1% | 97.3% | .37 | 94.7% | 95.1% | .30 | 92.5% | 93.0% | .29 | 90.2% | 90.9% | .31 | 87.9% | 88.7% | .36 |

| CLI | 86.9% | 88.2% | .01 | 80.6% | 82.5% | .01 | 76.2% | 78.5% | .01 | 70.2% | 73.0% | .01 | 66.4% | 69.5% | .04 |

| Endovascular | 92.0% | 93.1% | .01 | 87.3% | 89.0% | .001 | 82.5% | 84.7% | <.001 | 78.0% | 80.7% | .001 | 72.8% | 76.0% | .002 |

| Claudication | 97.1% | 97.4% | .55 | 94.9% | 95.3% | .50 | 91.5% | 92.2% | .45 | 89.1% | 90.0% | .44 | 85.4% | 86.6% | .46 |

| CLI | 89.9% | 91.3% | .02 | 84.1% | 86.1% | .01 | 78.9% | 81.5% | .01 | 73.4% | 76.5% | .01 | 66.9% | 70.6% | .01 |

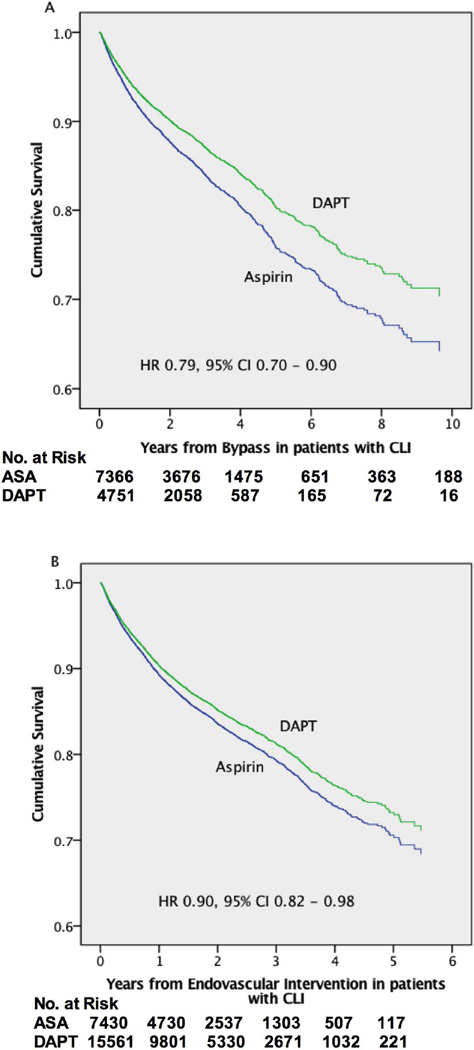

Using Cox proportional hazards models for the entire sample we found similar results with a protective effect for DAPT after both bypass (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.72 – 0.90) and endovascular interventions (HR 0.89, 0.83 – 0.95)(Table V)(Supplemental Figure 1). This protective effect remained after adjusting for discharge on anticoagulation (bypass: HR 0.83, 0.74 – 0.92; endovascular: HR 0.91, 0.84 – 0.97). In-hospital post-operative myocardial infarction is reported in bypass patients only and occurred at a higher rate in the DAPT group (3.7% vs. 2.0%, P < .001). After adjustment for post-operative myocardial infarction the protective effect of DAPT was similar (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.74–0.92). When stratified by PAD severity, patients with CLI discharged on DAPT had improved survival (Bypass: HR 0.79, 0.70 – 0.90; Endovascular: HR 0.90, 0.82 – 0.98)(Figure 1) but those with claudication did not (Bypass: HR 1.12, 0.75 – 1.68; Endovascular: HR 0.89, 0.77 – 1.03).

Table V.

Adjusted Long-term Mortality for patients undergoing Bypass and Endovascular intervention

| Bypass | Endovascular | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | P-value | HR | 95%CI | P-value | |

| DAPT (vs. Aspirin) | 0.81 | 0.72–0.90 | <.001 | 0.89 | 0.83–0.95 | .001 |

| Age (by year) | 1.04 | 1.04–1.05 | <.001 | 1.04 | 1.04–1.05 | <.001 |

| Female | 1.04 | 0.95–1.14 | .45 | 1.0 | 0.94–1.07 | .90 |

| White race | 1.41 | 1.23–1.61 | <.001 | 1.26 | 1.17–1.37 | <.001 |

| Smoker | ||||||

| None | ref | ref | ||||

| Previous | 1.14 | 1.02–1.29 | .03 | 1.01 | 0.94–1.09 | .76 |

| Current | 1.26 | 1.10–1.43 | .001 | 1.22 | 1.12–1.34 | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 1.12 | 1.03–1.23 | .01 | 1.12 | 1.05–1.19 | .001 |

| CAD | 1.17 | 1.06–1.30 | .003 | 1.2 | 1.12–1.29 | <.001 |

| CHF | 1.60 | 1.45–1.78 | <.001 | 1.57 | 1.56–1.79 | <.001 |

| Symptoms | ||||||

| Claudication | ref | ref | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 0.97 | 0.75–1.26 | .84 | 0.6 | 0.52–0.69 | <.001 |

| Rest pain | 1.34 | 1.04–1.74 | .02 | 1.08 | 0.92–1.26 | .35 |

| Tissue Loss | 2.03 | 1.59–2.60 | <.001 | 1.5 | 1.30–1.72 | <.001 |

| Acute Limb Ischemia | 2.06 | 1.57–2.69 | <.001 | 1.28 | 1.09–1.52 | .003 |

| Abnormal stress test | 1.16 | 1.02–1.32 | .02 | 0.95 | 0.84–1.08 | .44 |

| Renal dysfunction | 1.74 | 1.51–2.0 | <.001 | 1.73 | 1.57–1.91 | <.001 |

| Hemodialysis | 3.33 | 2.91–3.81 | <.001 | 3.2 | 2.93–3.50 | <.001 |

| Prior Procedures | ||||||

| CABG/PCI | 1.02 | 0.92–1.13 | .70 | 1.06 | 0.99–1.14 | .10 |

| CEA/CAS | 1.11 | 0.97–1.27 | .13 | 1.1 | 0.99–1.22 | .08 |

| Lower ext. revasc. | 1.05 | 0.96–1.15 | .29 | 0.97 | 0.91–1.04 | .36 |

| Major Amputation | 1.33 | 1.11–1.58 | .002 | 1.24 | 1.10–1.40 | <.001 |

| Urgent (vs. elective) | 1.13 | 1.02–1.25 | .02 | 1.29 | 1.19–1.39 | <.001 |

| Perioperative Antiplatelet | ||||||

| Mono-antiplatelet | ref | ref | ||||

| DAPT | 1.03 | 0.91–1.18 | .61 | 1.05 | 0.97–1.14 | .20 |

| No Antiplatelet | 0.97 | 0.85–1.09 | .59 | 1.03 | 0.94–1.13 | .54 |

| Perioperative Anticoagulation | 1.29 | 1.09–1.52 | .002 | 1.14 | 1.04–1.24 | .01 |

| Discharged on Statin | 0.80 | 0.71–0.87 | <.001 | 0.8 | 0.75–0.86 | <.001 |

When discharged on any anticoagulation included in above model DAPT remains protective for Bypass (HR 0.83, 95%CI 0.74 – 0.92) and endovascular interventions (HR 0.91, 95%CI 0.84 – 0.97)

Figure 1.

Cumulative adjusted survival for patients with CLI undergoing (A) Bypass and (B) Endovascular intervention

Discussion

This analysis demonstrates that patients discharged on DAPT after lower extremity bypass and endovascular interventions had improved long-term survival compared to those on Aspirin alone. This benefit was most evident in patients with more severe PAD, specifically those with limb threatening ischemia that underwent revascularization.

The American Heart Association (AHA)/American College of Cardiology (ACC) has given level 1A recommendations for DAPT in patients following acute coronary syndrome or after placement of a drug-eluting coronary stent for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular events.[10] The benefit to DAPT in this setting is thought to not only be from prevention of stent thrombosis but also from a decrease in atherothrombotic events in coronary vessels outside of the stented artery.[15] This is further supported by evidence that medically managed patients with acute coronary syndrome had fewer subsequent MIs on DAPT compared to aspirin and placebo in the CURE trial and lower composite stroke, MI, and cardiovascular death for patients with a history of MI one to three years prior, in the Pegasus-TIMI 54 trial.[24, 25] At the cellular level Aspirin and Clopidogrel act through different mechanisms to inhibit platelets, and prior studies have already shown the synergistic effect of DAPT, on limiting platelet activation and aggregation, as well as improved anti-inflammatory effects, compared to Mono therapy alone in high-risk populations.[18, 19, 24]

The strength of evidence supporting current guidelines for antiplatelet therapy in PAD is weak overall, especially after intervention. The strongest evidence exists for mono-antiplatelet therapy in patients with symptomatic PAD, endorsed with high quality research by numerous society consensus guidelines including, the Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS), the AHA/ACC, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP), and the Trans-Atlantic Inter-Society Consensus (TASC). [1, 9, 10, 16, 26–33]

The evidence is less clear for DAPT in symptomatic PAD with the AHA/ACC guidelines stating DAPT therapy may be considered, citing Class IIb rated evidence; the TASC guidelines refraining from making any recommendations for or against DAPT, citing insufficient evidence; the ACCP recommending against DAPT in symptomatic PAD, citing Grade 2B evidence; and SVS stating that there is no evidence to date demonstrating that DAPT is more effective than mono-antiplatelet therapy in patients with claudication. For those PAD patients progressing to intervention, the ACCP goes one step further and specifically recommends for mono-therapy and against DAPT after endovascular procedures, based on Grade 2C evidence. This recommendation was based on the overall lack of difference in the CHARISMA trial.[13] In addition, although a subsequent sub-group analyses showed a difference for symptomatic PAD, this was considered low grade evidence as it was not a pre-specified analysis.[21] The lack of clear recommendations was reflected in the practice patterns for discharge medications seen in our study.

In 2015 Armstrong et al. published a single-institution series that evaluated DAPT versus Aspirin mono-therapy in 629 patients with claudication and CLI (proportion with CLI: Aspirin mono-therapy 54%, DAPT 56%), 80% of whom underwent an intervention, and found that DAPT was associated with a significant decrease in mortality and MACE but not amputation; this finding was contrasted with the subgroup analysis of PAD patients from the CHARISMA trial, which found a reduction in MI (2.3% vs. 3.7%) and hospitalizations for ischemic events (17% vs. 20%) but no significant reduction in MACE or death for patients on DAPT (7.6% vs. 8.9%, P = .18).[20, 21] CHARISMA, however, was designed to compare a diverse set of patients with documented or multiple risk factors for cardiovascular disease, of which approximately 22% had PAD, calling the sub-group analysis into question. A critical difference between the two studies is that approximately half the patients in the Armstrong study having CLI compared to most having claudication in the CHARISMA trial, with additional inclusion of some asymptomatic patients based on ABI < 0.85. Similar to the Armstrong study, approximately half of the patients in our endovascular sample and more than half in our bypass sample presented with either CLI or ALI and, furthermore, we were able to adjust for tissue loss as well as acute limb ischemia. Additionally, all patients included in our study underwent intervention, whereas in Armstrong et al. 20% underwent diagnostic angiography only and in CHARISMA it was unclear how many, if any, underwent intervention for PAD. Our study supports the claim that the survival benefit is seen primarily in CLI patients, presumably because of a greater atherosclerotic burden and therefore higher risk for subsequent cardiovascular events. We did not find any benefit in patients with claudication, further supporting this point.

Patients undergoing bypass in our analysis had more advanced PAD, with higher proportions of tissue loss and ALI, compared to those undergoing endovascular intervention. If we use severity of PAD as a surrogate for severity of coronary disease, and therefore risk of cardiovascular death, we hypothesize that patients undergoing bypass would stand to benefit more from DAPT, which our data support. However, many of the bypass patients on DAPT were likely discharged on DAPT because they were on it prior to the operation for cardiac reasons and thus more likely to remain on DAPT long-term compared to patients undergoing endovascular intervention, who would typically be discharged on 30–90 days of DAPT and would then resume a mono-antiplatelet regimen thereafter if they were not on DAPT preoperatively. Our data showed that the proportion on DAPT after bypass was much smaller than the proportion on DAPT after endovascular intervention, but within each respective DAPT cohort the proportion of patients on DAPT preoperatively were similar. We think this still fits with the prior reasoning as we presume that many bypass patients come into the hospital on DAPT for cardiac reasons and that many of the endovascular patients are placed on DAPT just prior to the endovascular intervention by the treating physician during the planning and preadmission workup. Our long-term data are missing too much information to evaluate this, however. It is important to mention that the endovascular cohort after weighting still had more elective cases in the DAPT group but adjusting for this in the overall Cox model showed that DAPT remained protective in these patients. Additionally, both models account for pre-procedural DAPT as well.

Patients on DAPT were also younger but, as expected, had more coronary artery disease and prior coronary revascularization. They also had more risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including hypertension and diabetes, although, unexpectedly, they had lower rates of chronic kidney disease in the endovascular cohort.[34] Such differences likely contribute to a provider’s initial choice to prescribe DAPT compared to mono-antiplatelet therapy. Patients on DAPT also had a greater proportion of prior major vascular operations, suggesting this group was sicker in general. We therefore perform additional sensitivity analyses using Cox proportional hazards models to further validate our findings since subtle, but important differences, such as prior lower extremity or carotid revascularization, persisted in our weighted samples. Use of Statins previously have been shown to protect against mortality and so we also adjusted for statin use in the Cox models in the unweighted sample. Even after adjustment for all notable differences in the unweighted cohort we continued to see the same protective effect of DAPT, compared to Aspirin alone, after bypass and endovascular intervention.

Our survival was slightly higher than reported by Siracuse et al., who found crude 3-year survival ranged from 70% to 85% in patients undergoing revascularization in the VQI for CLI.[35] This is likely from the exclusion of all emergent cases and patients not on an antiplatelet agent at discharge from our analysis. Our study and Siracuse et al. had better survival than previously reported in randomized controlled trials, although the proportion of tissue loss was quite different between those trials and the VQI.[36, 37]

Prolonged DAPT has the potential for multiple complications as well, including bleeding, but unfortunately we could not determine the cause of death nor could we evaluate readmissions/reinterventions for bleeding or thrombotic complications with the current data.

Prescribing patterns at discharge in our analysis suggest that many treating clinicians feel DAPT is more appropriate after endovascular intervention in the lower extremities compared to bypass. Guidelines from AHA/ACC, TASC, and ACCP don’t appear to distinguish between types of intervention for symptomatic PAD within their recommendations. Only one of the three RCTs to date evaluating DAPT after lower extremity revascularization evaluated endovascular interventions in particular.[38] Whether this preference is based on anecdotal evidence within providers or as a result of strong evidence existing for percutaneous coronary intervention, remains unclear.[39]

This study has several limitations: first, cause of death was missing in this analysis so identification of cardiovascular-related death was not possible although data from prior studies suggests this is likely the most common cause of death.[21] Second, missing data, in terms of other medications such as anticoagulation and long-term follow-up data for antiplatelet agents, makes it difficult to assess the full effect of other medications and the duration of antiplatelet therapy. Our long-term data shows few patients crossing over from Mono to DAPT, although missing data limit our ability to interpret how this might have impacted our conclusions. Missing data also prevents us from analyzing important additional secondary endpoints, such as amputation, bleeding, patency, or reintervention. If anything the benefit of DAPT was underestimated in this analysis with a large minority in those with follow-up data available deescalating from DAPT to Mono therapy within a year. We are also not able to generalize to excluded patients, such as those on mono-P2Y12 antagonists, who could potentially have differing results. In addition, major adverse cardiovascular event rates, a common endpoint for this population, could not be calculated as we had insufficient data on stroke and myocardial infarction after discharge. However, Armstrong et al. showed that death is a reasonable surrogate for MACE in this population.[20] It was also difficult to know how much to adjust for, as many potential variables could be considered either confounding or collinear with respect to the decision to place a patient on DAPT versus Aspirin at time of discharge. We chose a conservative and inclusive approach to our models, to over-adjust in both our propensity score calculation and Cox proportional hazard models. As a result we likely underestimate the full survival benefit of DAPT, where benefit was found. Finally, the benefits of antiplatelet therapy in PAD on adverse limb events have been variable in prior work but unfortunately our analysis could not better clarify this matter due to limited follow-up data. In particular we are unable to quantify and factor into our analysis any differences in post-discharge bleeding complications between the two groups due to insufficient follow-up data. Such questions will be important for future analyses to improve identification of patient’s who stand to benefit from DAPT and those who may be harmed.[40]

Conclusion

DAPT at time of discharge, compared to Aspirin alone, is associated with increased survival after lower extremity revascularization. This benefit was most evident in patients with critical limb ischemia. Given these findings there is a need to quantify the risk associated with DAPT, especially with regard to bleeding, so that clinicians can choose appropriate antiplatelet management for their patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grant 5R01HL105453-03 from the NHLBI and the NIH T32 Harvard-Longwood Research Training in Vascular Surgery grant HL007734.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented as Podium Presentation at the 42nd Annual New England Society for Vascular Surgery Meeting, October 2–4, 2015 in Newport, RI

References

- 1.Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, Nehler MR, Harris KA, Fowkes FG, et al. Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II) J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(Suppl S):S5–S67. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopez AD, Murray CC. The global burden of disease, 1990–2020. Nat Med. 1998;4(11):1241–1243. doi: 10.1038/3218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirsch AT, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, Regensteiner JG, Creager MA, Olin JW, et al. Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. JAMA. 2001;286(11):1317–1324. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.11.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Wilson PW, D'Agostino R, Ohman EM, Rother J, et al. One-year cardiovascular event rates in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA. 2007;297(11):1197–1206. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.11.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welten GM, Schouten O, Hoeks SE, Chonchol M, Vidakovic R, van Domburg RT, et al. Long-term prognosis of patients with peripheral arterial disease: a comparison in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(16):1588–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.11.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Criqui MH, Langer RD, Fronek A, Feigelson HS, Klauber MR, McCann TJ, et al. Mortality over a period of 10 years in patients with peripheral arterial disease. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(6):381–386. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202063260605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Criqui MH, Ninomiya JK, Wingard DL, Ji M, Fronek A. Progression of peripheral arterial disease predicts cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(21):1736–1742. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Ohman EM, Hirsch AT, Ikeda Y, Mas JL, et al. International prevalence, recognition, and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA. 2006;295(2):180–189. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vandvik PO, Lincoff AM, Gore JM, Gutterman DD, Sonnenberg FA, Alonso-Coello P, et al. Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e637S–e668S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith SC, Jr, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, Braun LT, Creager MA, Franklin BA, et al. AHA/ACCF Secondary Prevention and Risk Reduction Therapy for Patients with Coronary and other Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2011;124(22):2458–2473. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318235eb4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Committee CS. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). CAPRIE Steering Committee. Lancet. 1996;348(9038):1329–1339. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)09457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatt DL, Fox KA, Hacke W, Berger PB, Black HR, Boden WE, et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(16):1706–1717. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhatt DL, Flather MD, Hacke W, Berger PB, Black HR, Boden WE, et al. Patients with prior myocardial infarction, stroke, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the CHARISMA trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(19):1982–1988. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, Liu L, Wang D, Wang C, et al. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(1):11–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mauri L, Kereiakes DJ, Yeh RW, Driscoll-Shempp P, Cutlip DE, Steg PG, et al. Twelve or 30 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stents. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(23):2155–2166. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conte MS, Pomposelli FB. Society for Vascular Surgery Practice guidelines for atherosclerotic occlusive disease of the lower extremities management of asymptomatic disease and claudication. Introduction. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61(3 Suppl):1S. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ricco JB, Parvin S, Veller M, Brunkwall J, Wolfe J, Sillesen H, et al. Statement from the European Society of Vascular Surgery and the World Federation of Vascular Surgery Societies: Transatlantic Inter-Society Consensus Document (TASC) III and International Standards for Vascular Care (ISVaC) Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2014;47(2):118. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bossavy JP, Thalamas C, Sagnard L, Barret A, Sakariassen K, Boneu B, et al. A double-blind randomized comparison of combined aspirin and ticlopidine therapy versus aspirin or ticlopidine alone on experimental arterial thrombogenesis in humans. Blood. 1998;92(5):1518–1525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moshfegh K, Redondo M, Julmy F, Wuillemin WA, Gebauer MU, Haeberli A, et al. Antiplatelet effects of clopidogrel compared with aspirin after myocardial infarction: enhanced inhibitory effects of combination therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(3):699–705. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00817-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armstrong EJ, Anderson DR, Yeo KK, Singh GD, Bang H, Amsterdam EA, et al. Association of dual-antiplatelet therapy with reduced major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with symptomatic peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2015;62(1):157–165. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cacoub PP, Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Topol EJ, Creager MA, Investigators C. Patients with peripheral arterial disease in the CHARISMA trial. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(2):192–201. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cronenwett JL, Likosky DS, Russell MT, Eldrup-Jorgensen J, Stanley AC, Nolan BW, et al. A regional registry for quality assurance and improvement: the Vascular Study Group of Northern New England (VSGNNE) J Vasc Surg. 2007;46(6):1093–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.08.012. discussion 1101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curtis LH, Hammill BG, Eisenstein EL, Kramer JM, Anstrom KJ. Using inverse probability-weighted estimators in comparative effectiveness analyses with observational databases. Med Care. 2007;45(10 Supl 2):S103–S107. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31806518ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Tognoni G, Fox KK, et al. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(7):494–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonaca MP, Bhatt DL, Cohen M, Steg PG, Storey RF, Jensen EC, et al. Long-term use of ticagrelor in patients with prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(19):1791–1800. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fowkes FG, Price JF, Stewart MC, Butcher I, Leng GC, Pell AC, et al. Aspirin for prevention of cardiovascular events in a general population screened for a low ankle brachial index: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303(9):841–848. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belch J, MacCuish A, Campbell I, Cobbe S, Taylor R, Prescott R, et al. The prevention of progression of arterial disease and diabetes (POPADAD) trial: factorial randomised placebo controlled trial of aspirin and antioxidants in patients with diabetes and asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease. BMJ. 2008;337:a1840. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Writing Group M, Writing Committee M, and Accf/Aha Task Force M. 2011 ACCF/AHA Focused Update of the Guideline for the Management of patients with peripheral artery disease (Updating the 2005 Guideline): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2011;124(18):2020–2045. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31822e80c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rooke TW, Hirsch AT, Misra S, Sidawy AN, Beckman JA, Findeiss LK, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Focused Update of the Guideline for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Artery Disease (updating the 2005 guideline): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(19):2020–2045. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alonso-Coello P, Bellmunt S, McGorrian C, Anand SS, Guzman R, Criqui MH, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in peripheral artery disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e669S–e690S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Martino RR, Eldrup-Jorgensen J, Nolan BW, Stone DH, Adams J, Bertges DJ, et al. Perioperative management with antiplatelet and statin medication is associated with reduced mortality following vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59(6):1615–1621. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.12.013. 1621 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Society for Vascular Surgery Lower Extremity Guidelines Writing G. Conte MS, Pomposelli FB, Clair DG, Geraghty PJ, McKinsey JF, et al. Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines for atherosclerotic occlusive disease of the lower extremities: management of asymptomatic disease and claudication. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61(3 Suppl):2S–41S. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson JL, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Bozkurt B, Brindis RG, Curtis LH, et al. Management of patients with peripheral artery disease (compilation of 2005 and 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline recommendations): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127(13):1425–1443. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828b82aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38–e360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siracuse JJ, Menard MT, Eslami MH, Kalish JA, Robinson WP, Eberhardt RT, et al. Comparison of open and endovascular treatment of patients with critical limb ischemia in the Vascular Quality Initiative. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63(4):958–965. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bradbury AW, Adam DJ, Bell J, Forbes JF, Fowkes FG, Gillespie I, et al. Bypass versus Angioplasty in Severe Ischaemia of the Leg (BASIL) trial: Analysis of amputation free and overall survival by treatment received. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51(5 Suppl):18S–31S. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.01.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conte MS, Bandyk DF, Clowes AW, Moneta GL, Seely L, Lorenz TJ, et al. Results of PREVENT III: a multicenter, randomized trial of edifoligide for the prevention of vein graft failure in lower extremity bypass surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43(4):742–751. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.12.058. discussion 751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tepe G, Bantleon R, Brechtel K, Schmehl J, Zeller T, Claussen CD, et al. Management of peripheral arterial interventions with mono or dual antiplatelet therapy--the MIRROR study: a randomised and double-blinded clinical trial. Eur Radiol. 2012;22(9):1998–2006. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2441-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarode K, Mohammad A, Das S, Vinas A, Banerjee A, Tsai S, et al. Comparison of Dual-Antiplatelet Therapy Durations after Endovascular Revascularization of Infrainguinal Arteries. Ann Vasc Surg. 2015;29(6):1235–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2015.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yeh RW, Secemsky EA, Kereiakes DJ, Normand SL, Gershlick AH, Cohen DJ, et al. Development and Validation of a Prediction Rule for Benefit and Harm of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Beyond 1 Year After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1735–1749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.