Abstract

A key challenge for asylum seekers in the United States is being able to provide evidence of prior persecution in their home countries. Medical/psychological affidavits corroborating applicants’ accounts often make the difference between successful and unsuccessful applications. The purpose of this study was to identify the unmet demand for and features of effective medical/psychological affidavits in the asylum process, as well as the personal and systemic barriers for asylum seekers. This is a qualitative study of semi-structured interviews with legal professionals who work in asylum law. Sixteen asylum lawyers and one Board of Immigration Appeals accredited representative practicing in the state of Michigan, United States, participated in this study. All participants noted that a vast majority of their asylum cases would benefit from a medical affidavit but that they have difficulty finding qualified physicians with experience writing such affidavits and testifying as expert witnesses. The major barriers to obtaining medical/psychological evaluations included inability to pay for services, lack of practitioner availability, and lack of practitioner training. The participants reported that features of a strong medical affidavit included clear, concise, and corroborative accounts that supported the applicant’s story from a diagnostic perspective and forensic descriptions that reinforced the credibility of the applicant. Several also noted that medical/psychological evaluations frequently would reveal additional details and incidents of trauma beyond those stated in the applicant’s preliminary statement. The study results suggest substantial unmet need for trained physicians to perform medical and psychological evaluations on a pro bono basis. Lawyers’ recommendations regarding effective medical affidavits and necessary ongoing support for asylum applicants should inform current efforts to improve physician and lawyer collaborations on asylum cases.

Keywords: asylum seekers, asylum evaluation, human rights, forensic medicine, underserved care

BACKGROUND

A record number of people were displaced globally as a result of war, civil conflict, and other mass humanitarian crises in 2014.1 Of the 59.5 million people who were forcibly displaced, more than 1.66 million applied for asylum, approximately 120,000 of whom did so in the United States.1–3 As an example of the recent influx of asylum applicants, the Chicago Asylum Office, which covers a 15 state jurisdiction, received 490 asylum applications in March of 2015 and had 6,485 cases pending.4 This unprecedented increase in asylum claims in the United States has created a backlog of more than 45,000 applications in early 2014, with subsequent lengthening wait times and diminished legal resources for applicants.3

The ability to gain asylum in the United States, as in Europe and the United Kingdom, is determined on the basis of reasonable or credible fear of persecution, but places the burden of proof for this wholly on the asylum applicant.5 The 1951 United Nations Convention on the Status of Refugees described asylum seekers as those who meet the definition of refugee but are already residing in country or are requesting sanctuary at a port of entry.6,7 Those who petition must be able to prove that “race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion was or will be at least one central reason” for fear of persecution should they return to their country of origin.6,8 A key challenge for applicants is being able to provide evidence of prior persecution in their home countries. Many who seek refuge have fled their homes under urgent circumstances and after reaching the United States may find it difficult or impossible to locate compelling evidence from abroad.9 Thus, the claim for asylum often hinges upon the physical or psychological manifestations of trauma that applicants carry with them: the body becomes “the place that displays the evidence of truth.”10

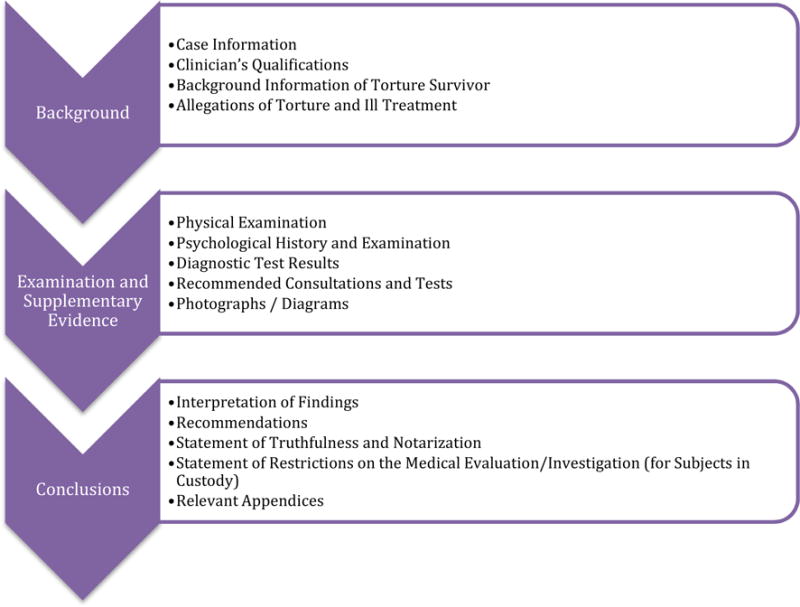

A forensic medical examination by a trained clinician can offer crucial corroborative support for an asylum seeker’s claim through written documentation of the physical and psychological sequelae of torture or other forms of persecution.11 These medical/psychological evaluations generally cover standard domains (Figure 1) and are written, notarized, and submitted to the court as a “medical affidavit,” or medical-legal report, in support of the asylum applicant’s claim.9 However, while such reports corroborating applicants’ accounts often make the difference between successful and unsuccessful applications, little is known about unmet demand for and features of effective medical affidavits in the asylum process.12,13

Figure 1.

Domains Covered in the Medical/Psychological Affidavit9

Although there have been few comprehensive efforts to train health professionals on the recognition and documentation of torture, several curricular models and asylum clinics have been implemented at medical schools in the United States in recent years.14 The new emphasis on such training for physicians and other health professionals indicates a recognition of the growing number of survivors of torture and other human rights violations living in the United States and the obligation of physicians to care for these individuals.15 In light of the legal situation of asylum seekers, physicians conduct their evaluations in a unique context that calls for a strong collaboration between physicians and legal parties. Considering this collaborative necessity and given the significant gaps in knowledge regarding medical affidavits, the purpose of this qualitative study was to gather lawyers’ perspectives about the unmet need for evaluations, the features of effective medical/psychological affidavits, and the personal and systemic barriers that asylum seekers face.

METHODS

This study employed a qualitative ethnographic approach to understand legal professionals’ common experiences with medical affidavits. We felt that qualitative interviews were necessary to understand the context of working with asylees in the legal system, given the complexity and nuance implicit in the collaborative work between medical and legal providers in the field.

Sampling and Data Collection

We conducted semi-structured interviews with 17 legal professionals who work in the area of immigration with experience in asylum law in the United States. Five initial participants were identified through the medical-legal partnership within the University of Michigan Asylum Collaborative, a medical student-led initiative established in 2013 that provides medical and psychological evaluations for asylum seekers. Further candidates were selected through snowball sampling from three categories of practice: university law school clinic, non-profit organization, and private firm. From a compiled list of 40 legal professionals, 11 did not respond to email or phone queries; 4 declined to be interviewed because they had either not taken asylum cases in many years or they did not routinely use medical evaluations in their cases; 4 were not contacted because they worked for the same organization as previous respondents who answered on behalf of their firm, NGO, or university clinic; 1 had moved to another state since being placed on the list. Furthermore, 3 were not contacted because saturation had been reached, i.e., content revealed no new information.16 The interview format consisted of background questions related to the participant’s legal practice in asylum law, followed by questions pertaining to the use of medical and psychological evaluations for asylum claims. Interviews lasted between 40–75 minutes and were conducted in person or via telephone. One member of the research team conducted all interviews. Verbal informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to beginning the interview. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan approved the study.

Data Analysis

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. A thematic qualitative text analysis was applied to review transcripts and develop themes.16,17 An initial codebook of recurring themes (e.g., characteristics of an effective evaluation) was constructed using an iterative process with all team members to achieve agreement. Team members evaluated coding independently and then met to discuss results as a group. Six of the seventeen interviews were coded by all team members, who resolved coding discrepancies and reached agreement through consensus.18,19 Two researchers coded the remaining 11 interviews using the finalized codebook. The analytical software MAXQDA was used to compile all text segments according to their established codes.20 All team members reviewed a completed report with recurring themes and illustrative quotes to ensure the validity of the thematic summary. A summary was provided to three of the legal professionals interviewed to check the accuracy of findings through member checking.16 Two responded with minimal comments and indicated the findings were accurate.

RESULTS

Sample Description

Seventeen legal professionals were interviewed for this study. Participants were divided into three main categories of practice: university law school clinic (6), nonprofit organization (6), and private firm (5). All are practicing attorneys with the exception of one participant who works as a non-attorney accredited by the Board of Immigration Appeals to represent immigration clients on a pro bono basis. Eleven of the seventeen solely accept asylum cases pro bono, while the other six represent clients on a sliding scale. Ten practice in the Detroit region of Michigan, and the remaining seven are located in other areas of the state. Average years in practice are approximately 17, and range from 4 – 41 years. Estimated total number of asylum cases handled during their careers ranged from 15 to 200 cases.

Key Themes from Interviews

Every one of the interviewed legal professionals reported they had had difficulties obtaining physicians’ affidavits for their clients, especially on a pro bono basis. The most prominent themes to emerge were the challenge of locating a trained clinician, the need for experienced physician collaborators to conduct the evaluation, and the importance of a physician’s testimony before an asylum court to supplement the medical affidavit. The themes detailed below represent the consensus among all of those interviewed except where otherwise indicated.

Obtaining an Evaluation

“You feel like you’ve won the lottery to get someone who really knows what they’re doing. But mostly I didn’t have that.” (Pro bono/nonprofit)

All of the legal professionals interviewed noted that a vast majority of their asylum cases would benefit from an evaluation but that they have difficulty finding qualified physicians with experience writing medical affidavits and testifying as expert witnesses. While familiarity with asylum law is preferred, a lack of training, lack of experience, or lack of specialization related to the case is often overlooked in order to obtain an evaluation. As one lawyer noted, “It’s like you cobble together the best resources that you can and sometimes you come across somebody who’s excellent and you feel so fortunate, and whether that person’s going to have time to do it again, they may or may not” (Non pro bono/private firm).

Participants cited colleagues as their main source for referrals, but also reported locating physicians through family, friends, or in the case of law school clinics, through student interns. Many mentioned their hesitation to approach physicians without a frame of reference or outside connection, as exemplified by this lawyer’s statement: “If you don’t have a relationship with a doctor already, I would say it’s more difficult, just to cold-call a doctor and say, ‘Can you help us out here?’” (Non pro bono/private firm). There is also a desire to reserve the few contacts they have for those cases that they believe are especially in need of a medical or psychological evaluation to bolster the claim. This behavior reflects a fear of exhausting their physician contact, or as one participant said, “that sense of, you save your go-to people for when you really think you’re going to need them” (Pro bono/university clinic).

Valuable Physician Characteristics

“Somebody who is familiar with the immigration process and is familiar with what we’re looking for.” (Pro bono/university clinic)

Interviewees explained that it is especially helpful if physicians have experience working within the legal system, have knowledge of the immigration process, and are amenable to working with lawyers. The participants described other characteristics as important as well (Table 1). It is preferable that the physician evaluator be skilled in the language of the applicant whenever possible. Participants noted that proficiency in the language of the applicant is useful both to avoid translation errors and to help make the applicant feel more comfortable during the evaluation. Participants also stressed the importance of willingness to testify by the physician, especially with respect to those applicants who face an adversarial court. Testimony by a physician can enhance the validity of the medical affidavit and in particular resolve inconsistencies or doubts the judge may have with respect to diagnostic assertions.

Table 1.

Key Characteristics of Physicians that Asylum Legal Professionals Seek

| Code | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Proficiency in Language of Applicant | “For some types of evaluations it doesn’t matter, the client can bring an interpreter or translator, but for others where the person feels uncomfortable speaking about it with anyone, to have more people present during the evaluation just makes it that much more difficult.” (Non pro bono/private firm) |

| Willingness to Testify | “When a doctor can come in and testify [in court], then maybe the doctor can clarify things, because you have an opportunity to talk about it more, as opposed to being just confined to what’s within the four corners of the page of paper that the report is written on.” (Non pro bono/private firm) |

| Empathy | “It’s really important that the evaluators have some kind of experience with other cultures, some kind of familiarity with trauma and with how torture plays out around the world, because it’s really hard to believe the things that happen to clients, or that the client would be detained, and tortured, and then go back to doing political activity.” (Pro bono/university clinic) |

Participants noted that empathy is an essential quality in a physician and one that allows them to perform more effective evaluations as they establish better rapport with the applicant and better avoid prior judgment or bias. Part of being an empathetic physician involves a willingness to spend sufficient time with the client and to remember they are examining an individual who has experienced significant trauma. Participants underscored the need for physicians to keep the “whole person” in mind, “so that way our client feels comfortable talking to that person, showing that person injuries, scars on what might be private parts of their body” during the medical examination (Non pro bono/private firm).

Evaluating the Medical Affidavit

“Write it in non-medical terms while still being medical, if that makes sense. You have to know your audience.” (Pro bono/nonprofit)

A common problem reported with weak affidavits was that they frequently contained equivocal language or contradictory versions of events (Table 2). Ambiguous statements in the medical affidavit may seriously damage the applicant’s claim, although participants admitted that there can be a fine balance between vague associations and falsely confirmatory statements. They cited the level of detail as an important feature of a medical affidavit, but cautioned that overly detailed accounts could potentially harm an applicant’s case if they seemed to contradict the applicant’s preliminary declaration, and that these contradictions could be difficult to resolve. Several participants mentioned that physicians sometimes write medical affidavits in a professional lexicon that could confuse an asylum officer or immigration judge who lack medical training. Those interviewed did not discourage use of medical terminology, but argued that it should be accompanied by an explanation in “layman’s terms.”

Table 2.

Common Deficiencies of Medical Affidavits

| Codes | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Equivocal and vague language | “The hard thing with a lot of this is that there are nuances that the medical professional doctors are going to know well beyond anything we can figure, so walking that tight line between not overstating and saying things that are just not true because they’re stated too bluntly. You also don’t want to be too equivocal in a statement.” (Pro bono/university clinic) |

| Includes details of what happened in country of origin that contradict legal statement | “We’re putting in a 20-page declaration with this client, and if the doctor puts in a 10-page version of it, something’s missing or something’s slightly different, or the timing of two events is transposed, and then it’s just, ‘well, gee, there were 3 people in the room in our account, and there are 2 people in your account,’ so most of the time we don’t want [the affidavit] that detailed.” (Pro bono/university clinic) |

| Uses medical jargon that judges will not understand without defining terms | “I have no medical experience or knowledge, so give it to me in layman’s terms, and I know if I can understand it, then I know the [asylum] officer can understand it. Keep it simple, don’t use a lot of jargon in the letter, and then connect it to the topic at hand.” (Non pro bono/nonprofit) |

It was emphasized that an effective medical affidavit included clear, concise, and corroborative accounts of the applicant’s story from a diagnostic perspective, as well as descriptions that reinforce their credibility (Table 3). Participants look for a thorough description of the medical interview, including documentation of how often the physician and applicant met and the duration of those meetings. Both the psychological and physical exam should provide clear documentation that corroborates the applicant’s story. Participants stated that descriptions of psychological consequences are helpful in revealing the extent of trauma that manifests in the form of depression, anxiety, or PTSD. Descriptions of physical scars are frequently the most compelling aspects of a medical affidavit and can determine the outcome of an asylum case. Participants noted that such descriptive physical evidence should be well documented through written description or photographs. One lawyer, however, strongly opposed the use of photographs, feeling they could distract from otherwise powerful written descriptions of physical abuse. This divergence of opinion highlights the necessity of close communication between physician and legal professional in order for both to understand the needs and preferences of the legal team.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Effective Evaluations

| Codes | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Documents the physician’s evaluation process and all sources of evidence | “With the PTSD case, a history of how often they met with the individual, how many meetings, how much time they spent with them, you know what kind of testing they did as well, like psychological testing…we’ve got to have an understanding how we got to that opinion.” (Non pro bono/private firm) |

| “We’ll have a doctor read their declaration, and talk about the types of injuries or the way they present. Someone who’ll take the time and walk through and say, ’in preparation for this, I reviewed this, and then I examined the person in this way, or I met with this person three times.” (Pro bono/university clinic) | |

| Provides corroborative evidence unique to the applicant’s history | “We were representing an Iraqi asylum seeker. He said he had been tortured during the Hussein regime, and that he had scarring on his wrists and back. We sent him to see a doctor who we’d worked with in the past, who was able to write an evaluation saying that those injuries were consistent with what had happened to him there. Based at least in part on that, the case was approved.” (Non pro bono/private firm) |

| Describes psychological consequences of persecution | “We had a psych report talking about [how] they were traumatized and the PTSD… sometimes that can affect memory and describing that was helpful as well.” (Non pro bono/nonprofit) |

| “The rape has occurred somewhere else in the past, so getting medical evidence of that…you’re not going to get. But from the PTSD standpoint and getting the client to being willing to open up and talk to somebody in that context I think is very helpful.” (Non pro bono/private firm) | |

| Describes and documents all physical evidence | “For instance in an FGM case, you have to have it. If you don’t have it, you don’t have a shot because your entire case is based on this physical characteristic. If there was torture or physical abuse that should result in some kind of scarring or manifestation, what happens is that if you don’t have the medical exam, that’s seen as a lack of corroboration, a lack of credibility that will absolutely kill a case.” (Pro bono/university clinic) |

| “The most powerful was the scar on a young boy’s head from Cameroon where the police meant to hit the mother who was applying for asylum, and instead they hit the young boy with a baton on his head, and so he still had this scar, and it showed up very well on a photo.” (Pro bono/university clinic) | |

| “Do you prefer photos to be included in the affidavit?” “No. I do not. Because it’s so hard to capture scars. I find most of the time that it ends up minimizing what they’ve written.” (Pro bono/nonprofit) | |

| Yields new information | “We knew he had been injured but we didn’t know that his back had been broken, because he hadn’t told us about that. He had told about being electric shocked and all these other things, so we found out about his broken back [from the evaluation].” (Pro bono/university clinic) |

| “I had one client that didn’t tell us she had undergone FGM, and that became part of her claim after we did the medical evaluation…sometimes it’s just a question of the client being more comfortable with the doctor.” (Pro bono/university clinic) |

A further benefit of medical/psychological affidavits is that they may also reveal additional details or incidents of trauma not originally stated in the applicant’s preliminary declaration. Legal professionals remarked that new information is likely to result from a specific line of medical questioning that elicits another level of narrative detail. These new elements strengthen the application and sometimes become a central part of the asylum claim.

Barriers Asylum Seekers Face

“The whole asylum process, it’s about managing expectations. It’s a long time. It takes patience.” (Pro bono/nonprofit)

Participants stressed that asylum seekers face multiple personal and systemic barriers to obtaining a medical evaluation. Asylum applicants lack financial resources and social institutions are rarely in place or adequately funded to support them. Participants noted that in the absence of a pro bono physician, a medical/psychological evaluation often is not obtained. One lawyer expressed frustration at this lack of resources and its impact: “It is devastating that we provide the bare minimum of resources while these clients are waiting for their asylum to be granted, relying on the good will, quite literally, of nonprofits across the country” (Pro bono/private firm). Participants maintained that the asylum process is emotionally hard for applicants. As one lawyer said, “It’s very disheartening sometimes for people, psychologically, that want to be able to move on and there’s no way to tell them when they’re going to…have their opportunity to be heard” (Non pro bono/private firm).

DISCUSSION

Although some teaching hospitals have provided workshops or mini-courses to train physicians and other health care providers to conduct asylum examinations and write medical affidavits,14 the findings of this study indicate that there is still a lack of trained physicians able to meet the need of medical/psychological evaluations for asylum applicants. The legal professionals interviewed particularly stressed the difficulty of locating a skilled clinician who is willing to perform an evaluation and write an affidavit on a pro bono basis. These findings support prior commentaries by physicians who themselves routinely conduct forensic evaluations for asylum applicants.21,22 We believe that a concerted effort is required to increase the number of trained physician evaluators to address this unmet need. Given the educational precedent calling for an introduction to human rights programming in medical school curricula,23–25 it seems apparent that support of and growth in this area could encourage young physicians to take an active role in using their medical skills to aid asylum seekers through the provision of medical/psychological evaluations.

A unique aspect of this study was its focus on the legal perspective on medical affidavits and features of successful medical-legal collaborations. Communication between medical and legal providers has not been emphasized in earlier studies, whose attention has been on training clinicians to recognize and document physical and psychological torture.21,22,26,27 Yet, participants consistently underscored the need for strong medical-legal partnerships throughout the evaluation process. Similar to the findings of Wilson-Shaw et al., whose work examined legal representatives’ subjective assessments of asylum seekers’ mental health in the UK, the legal professionals interviewed acknowledged their lack of familiarity with medical diagnoses and indicated a strong interest in fostering communication and cross-discipline education.28 The legal standards in place for asylum are complex and may be unfamiliar to most health professionals, especially evident with respect to equivocal statements by the physician when determining the client’s credibility.22 Legal professionals in this study expressed a desire to collaborate with physician evaluators to help them negotiate the legal requisites when submitting a medical/psychological affidavit for an asylum case.

Cooperative efforts may also prevent problems surrounding the level of detail necessary for an asylum applicant’s claim. UK and European guidelines compiled from years of experience writing medical reports, in addition to the internationally recognized Istanbul Protocol (IP), exist to aid physicians in the documentation of evidence during a medical evaluation.29,30 The IP in particular is considered the standard reference for clinicians, providing both the framework for performing physical and psychological examinations as well as guidelines for managing inconsistencies in a client interview.30 Our findings imply that not all types of documentation are universally accepted or desired by legal professionals representing asylum applicants and may be very context-specific. Although the IP acts as a detailed reference, it does not provide the country- or conflict-specific guidance that would be best provided by the client’s lawyer. As we have mentioned, participants were divided on the value of photographic evidence in the medical affidavit. This finding suggests that legal and medical professionals should establish clear expectations prior to the evaluation and maintain communication throughout the process. Similarly, new information revealed during the course of an evaluation requires the physician to communicate directly with the legal professional to clarify any inconsistencies before the written affidavit is produced.

Our findings concerning lawyers’ desire for experienced, trained physicians with knowledge of the legal system suggest that learning how to conduct medical evaluations for survivors of persecution cannot be limited to a one-time exposure. Long-term mentorship and feedback from experienced physicians is essential. Educating health professionals using internationally recognized manuals and experts in the field resolves some of the uncertainty regarding the provision of documentary evidence of acts of torture.26 It is critically important that subjects covered during standard training for health professionals such as asylum law, medical and psychological sequelae of torture, and approaches to minimize re-traumatization are reinforced through continual practice and mentoring in the field with skilled clinicians. Experience and practice will often make the difference between a strong evaluation and one that fails to provide the corroborative evidence necessary to support an applicant’s claim. Furthermore, physicians who are just beginning to evaluate asylum seekers could benefit from access to a resource database where vetted and accepted templates, literature, and sample case reports could be available for review. This database could expand upon the resources provided through Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) and the Weill Cornell Center for Human Rights (WCCHR),31,32 and could offer a forum for information exchange between legal and medical providers, to share best practices and also provide counsel, both medical and legal, to colleagues working in the field.

One limitation of this study was its narrow geographic sampling of legal professionals whose work in asylum law is defined by the court environment of the Chicago Asylum Office in the United States. Participants noted that judicial discretion can vary by jurisdiction and may result in varying experiences. However, given federal legislation and the underlying United Nations protocol that inform asylum law, participant responses are likely transferrable and reflect common trends in the need for medical affidavits and their importance for successful applications. Also, no definitive statement can be made with respect to the weight of a medical evaluation on the decision to grant asylum, as asylum verdicts are given without commentary on an application’s strengths or weaknesses. Although Lustig et al indicated that grant rates are significantly higher for applications that include a medical affidavit,12 in some cases the asylee’s account may contradict the findings of the physician and thereby harm the case. Further research is necessary to understand how medical evaluations influence specific final decisions.

This study’s findings have several implications. It informs the work of existing asylum clinics as well as educational interventions for medical school human rights curricula for students and residents. We recommend that more training is necessary to write adequate evaluations, beginning at the medical school level but also targeting practicing physicians. A core of physicians accessible to lawyers, expanding on PHR’s network, would facilitate obtaining evaluations when needed. The interviewed lawyers urged physicians to become cognizant of legal considerations when conducting medical/psychological evaluations. Themes identified in this study provide a framework for a database composed of both medical and legal best practices. Understanding the necessary legal intersection with medical evaluation can help physicians new to the process appreciate the complexity of asylum. Further research should explore physicians’ motivations to perform asylum evaluations, building on the work of Mishori et al., in order to better understand and develop medical-legal partnerships.33

Finally, sufficient funding to ensure fair treatment of all asylum seekers is equally important. This study highlights the current lack of monetary support when applying for asylum and the added financial burden of obtaining a medical/psychological evaluation. Unequal resource allocation results in unequal treatment. We therefore recommend that asylum seekers be granted access to legal representation and medical/psychological assessments as a first step in the application process.

CONCLUSION

There is a lack of trained physicians to cover the need for medical/psychological affidavits for asylum applicants in the United States, suggesting that a more concerted effort is required to increase the number of physician evaluators. Connections should be facilitated between legal professionals and trained physicians willing to conduct pro bono examinations, and training for physicians should be reinforced through practice and partnership with the legal community. The recommendations regarding features of successful medical affidavits presented in this study inform current efforts to improve medical-legal collaborations working on asylum and other forms of relief.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Trained physicians are needed to perform medical/psychological evaluations on a pro bono basis

Barriers to asylum seekers include financial constraints and practitioner availability

Strong medical affidavits provide corroborative accounts from a diagnostic perspective

Medical/psychological evaluations sometimes reveal additional detail and incidents of trauma

Lawyers’ recommendations inform future medical-legal collaborations on asylum cases

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: The Student Biomedical Research Program through the University of Michigan funded this study. Supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK099108 and P30DK092926). We also acknowledge the support of the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research grant #UL1TR00043 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors: We are very grateful to all of the legal professionals who participated in this study, and to the University of Michigan Asylum Collaborative for their support and input on this project.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Timothy C. Guetterman, Email: tguetter@med.umich.edu.

Anna C. Meyer, Email: ameyer4@uwhealth.org.

Jamie VanArtsdalen, Email: jvanarts@med.umich.edu.

Michele Heisler, Email: mheisler@umich.edu.

References

- 1.UNHCR. World at war: UNHCR Global Trends Forced Displacement in 2014. UNHCR: UN Refugee Agency; Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/556725e69.html. Accessed March 3, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Justice Executive Office for Immigration Review. FY 2014 Statistics Yearbook. Available from: http://www.justice.gov/eoir/pages/attachments/2015/03/16/fy14syb.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2016.

- 3.Department of Homeland Security. Annual Report 2014: Citizenship and Immigration Services. Citizenship and Immigration Services Ombudsman U.S. Department of Homeland Security; Available from: https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/cisomb-annual-report-2014.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Asylum Division Quarterly Stakeholder Meeting: Affirmative Asylum Statistics for January, February, and March 2015. USCIS Asylum Division; Available from: https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Outreach/PED-2015-01-03-NGO-Asylum-Stats.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Homeland Security. § 208.16 Withholding of removal under section 241(b)(3)(B) of the Act and withholding of removal under the Convention Against Torture. Available from: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2012-title8-vol1/pdf/CFR-2012-title8-vol1-sec208-16.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2016.

- 6.Final act and Convention relating to the status of refugees. Geneva: 1951. United Nations Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Status of Refugees and Stateless Persons. [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Refugees and Asylum. USCIS; Available from: https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/refugees-asylum. Accessed March 3, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Immigration and Nationality Act INA: Act 208 – Asylum. USCIS; Available from: https://www.uscis.gov/iframe/ilink/docView/SLB/HTML/SLB/act.html. Accessed March 3, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Physicians for Human Rights. Examining Asylum Seekers: A Clinician’s Guide to Physical and Psychological Evaluations of Torture and Ill Treatment. 2nd. New York: PHR; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fassin D, D’Halluin E. The Truth from the Body: Medical Certificates as Ultimate Evidence for Asylum Seekers. Am Anthropol. 2005;107(4):597–608. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKenzie K. Medical Evaluation of Asylum Seekers. In: Annamalai A, editor. Refugee Health Care: An Essential Medical Guide. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2014. pp. 235–41. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lustig SL, Kureshi S, Delucchi KL, Iacopino V, Morse SC. Asylum grant rates following medical evaluations of maltreatment among political asylum applicants in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health. 2008;10(1):7–15. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asgary R, Charpentier B, Burnett DC. Socio-medical challenges of asylum seekers prior and after coming to the US. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013;15(5):961–8. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9687-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Metalios EE, Asgary RG, Cooperman N, Smith CL, Du E, Modali L, et al. Teaching residents to work with torture survivors: experiences from the Bronx Human Rights Clinic. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1038–42. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0592-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asgary R, Smith CL. Ethical and professional considerations providing medical evaluation and care to refugee asylum seekers. Am J Bioeth. 2013;13(7):3–12. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2013.794876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Creswell J. 30 Essential Skills for the Qualitative Researcher. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuckartz U. Qualitative text analysis: A guide to methods, practice and using software. London: Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Creswell J. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. 3rd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Kay KMB. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Cult Anthropol Methods J. 1998;10(12):31–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verbi GmbH. MAXQDA. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stadtmauer GJ, Singer E, Metalios E. An analytical approach to clinical forensic evaluations of asylum seekers: the Healthright International Human Rights Clinic. J Forensic Leg Med. 2010;17(1):41–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paasche-Orlow MK, Orlow J. I’ll bet my reputation–and other ways to misconstrue the concept of certainty when preparing medical affidavits for asylum applicants. Am J Bioeth. 2013;13(7):15–7. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2013.794877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leaning J. Human rights and medical education: Why Every Medical Student Should Learn the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. BMJ Br Med J. 1997;315(7120):1390–1. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7120.1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chastonay P, Zesiger V, Ferreira J, Mpinga EK. Training medical students in human rights : a fifteen- year experience in Geneva. Can Med Educ J. 2012;3(2):151–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asgary R. A call to teach medical students clinical human rights. Acad Med. 2013;88(3):298–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318280ce4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kjaerum A. Combating torture with medical evidence: the use of medical evidence and expert opinions in international and regional human rights tribunals. Torture. 2010;20(3):119–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banner J. Forensic medical examination of refugees who claim to have been tortured. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2005;26(2):125–30. Doi: 00000433-200506000-00005 [pii] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson-Shaw L, Pistrang N, Herlihy J. Non-clinicians’ judgments about asylum seekers’ mental health: how do legal representatives of asylum seekers decide when to request medico-legal reports? Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2012;3(18406) doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.18406. http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.18406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forrest D, Knight B, Hinshelwood G, Anand J, Tonge V. A guide to writing medical reports on survivors of torture. Forensic Sci Int. 1995;76(1):69–75. doi: 10.1016/0379-0738(95)01799-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.United Nations. Istanbul Protocol: Manual on the Effective Investigation and Documentation of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. New York and Geneva: UN; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Physicians for Human Rights. Asylum Network Resources. Available from: http://physiciansforhumanrights.org/asylum/asylum-network-resources.html. Accessed March 3, 2016.

- 32.Chelidze K, Sirotin N, Fabiszak M, Gallen Edersheim T, Clark T, Villegas L, et al. Documenting Torture Sequelae: The Weill Cornell Model for Forensic Evaluation, Capacity Building, and Medical Education. In: Lawrence BN, Ruffer G, editors. Adjudicating Refugee and Asylum Status: the role of witness, expertise, and testimony. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2015. pp. 166–79. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mishori R, Hannaford A, Mujawar I, Ferdowsian H, Kureshi S. “Their Stories Have Changed My Life”: Clinicians’ Reflections on Their Experience with and Their Motivation to Conduct Asylum Evaluations. J Immigr Minor Heal. 2016;18(1):210–8. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]