Abstract

Purpose

To identify baseline structural parameters that predict the progression of visual field (VF) loss in patients with open angle glaucoma.

Design

Multicenter cohort study.

Methods

Participants from Advanced Imaging for Glaucoma (AIG) study were enrolled and followed-up. VF progression is defined as either a confirmed progression event on Humphrey Progression Analysis or a significant (p<0.05) negative slope for VF index (VFI). Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography (FD-OCT) was used to measure optic disc, peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (NFL) and macular ganglion cell complex (GCC) thickness parameters.

Results

277 eyes of 188 participants were followed up for 3.7 ± 2.1 years. VF progression was observed in 83 eyes (30%). Several baseline NFL and GCC parameters, but not disc parameters, were found to be significant predictors of progression on univariate Cox regression analysis. The most accurate single predictors were the GCC focal loss volume (FLV), followed closely by NFL-GCC. An abnormal GCC-FLV at baseline increased risk of progression by a hazard ratio of 3.1. Multivariate Cox analysis showed that combining age and central corneal thickness with GCC-FLV in a composite index called “Glaucoma Composite Progression Index” (GCPI) further improved the accuracy of progression prediction. GCC-FLV and GCPI were both found to be significantly correlated with the annual rate of change in VFI.

Conclusion

Focal GCC and NFL loss as measured by FD-OCT are the strongest predictors for VF progression among the measurements considered. Older age and thinner central corneal thickness can enhance the predictive power using the composite risk model.

Introduction

In the initial evaluation of glaucoma patients, it is important to evaluate the risk of disease progression and the likely rate of visual field (VF) loss. Patients with higher risk of rapid progression could be followed more closely and treated more aggressively. Understanding an individual’s risk profile would allow for the rational use of medical, laser and surgical treatments, all of which have significant cost, compliance, and safety issues. A number of risk factors have been previously identified, and these include intraocular pressure (IOP)1–3 and its variability,4,5 corneal thickness,6,7 cup-to-disc ratio, age, VF parameters,8,9 and optic disc hemorrhage.10,11 Family history and race also provide risk information. Photographic evidence of NFL defect1 and evidence of disc rim defect 12 have also been recognized as risk factors for VF loss. 13,14 In a recent meta-analysis, 15 Ernest et al. identified a list of recognized baseline prognostic factors for future VF loss, including disc hemorrhage (for normal tension glaucoma), VF loss, IOP and exfoliation syndrome, while a definitive association was not proven for other factors, such as family history. However, none of these risk factors by themselves are reliable predictors of glaucoma progression, and clinicians must consider all of them in glaucoma patient management.

Advanced imaging technologies can quantify glaucomatous damage to retinal neural structures and may provide useful prognostic information, since structural damage often precedes VF damage 16,17 Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography (FD-OCT), in particular, provides 3-dimensional imaging that measures the neural structures of the retina and optic nerve head with excellent resolution.18,19

The Advanced Imaging for Glaucoma (AIG) Study was designed to identify the role of quantitative imaging in evaluating the risk of glaucoma progression, and in early diagnosis of glaucoma and clinical decision-making.20 The purpose of this article is to identify baseline FD-OCT structural predictors for the progression of glaucomatous visual field (VF) defects, using the longitudinal AIG Study perimetric glaucoma cohort.

Methods

Longitudinal Clinical Study

The Advanced Imaging for Glaucoma (AIG) study is a multi-center bioengineering partnership and longitudinal cohort study sponsored by the National Eye Institute (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01314326). The data analyzed in this article came from participants in the perimetric glaucoma (PG) arm of the AIG Study.20 These participants were enrolled at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami; the Doheny Eye Institute (then affiliated with University of Southern California), and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Eye Institute. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of each participating university approved the study protocol. The study was in agreement with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects using the consent forms approved by the IRBs of the participating institutions. The study was in accordance with The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPPA) privacy and security regulations. Eyes enrolled in the PG group had glaucomatous optic neuropathy as evidenced by diffuse or localized thinning of the neuroretinal rim or NFL defect on fundus examination, and corresponding repeatable abnormal standard automated perimetry (SAP) defects with glaucoma hemifield test (GHT) or pattern standard deviation (PSD, p < 0.05) outside normal limits.

All study participants underwent a baseline examination20 consisting of a complete ophthalmic examination with VF and advanced glaucoma imaging (OCT, confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy, and scanning laser polarimetry) and had follow-up visits with repeat testing every six months. During the follow-up period, each patient was treated at the discretion of the attending physician. The study design and baseline participant characteristics have been previously published20 and the manual of procedures could be found at www.aigstudy.net.

Visual Field Progression Detection

Two methods of visual field progression detection were adopted: (1) event-based progression analysis, and (2) trend-based progression analysis. Event-based visual field progression was determined using Guided Progression Analysis (GPA; Humphrey Field Analyzer; Software version 4.2, Carl Zeiss Meditec Inc, Dublin, CA). GPA uses statistical criteria designed for the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial (EMGT) and compares the sensitivity values of individual test locations on follow-up visual fields to the sensitivity values of the same locations on an average of 2 baseline exams. An automated analysis identifies the locations that show change greater than the expected variability (at the 95% significance level). Event-based Progression was defined as a significant change detected in ≥3 test locations, and repeated at the same locations in 3 consecutive follow-up examinations, categorized by the GPA software as “Likely Progression”.

Trend-based visual field progression was defined as a significant (p < 0.05) negative slope in the annual rate of change in the visual field index (VFI). The VFI is a calculated index allocated to each visual field that determines the level of abnormality of the field.21 The VFI uses the pattern deviation (PD) probability map to identify the test locations that are considered either normal and scored as 100%, or absolute defect and scored as 0%. The remaining test locations with relative loss on PD plot are scored in percentage based on their total deviation (TD) value and age-corrected normal threshold.21 The occurrence of Trend-based Visual Field Progression was defined as the first follow-up visit reaching a significant (p<0.05) negative VFI slope over time. Visual field progression endpoint was reached when either type of progression was observed.

Fourier-domain Optical Coherence Tomography

Participants were scanned every 6 months with a commercial FD-OCT system (RTVue-100, Optovue Inc., Fremont, CA, USA). During each visit, participants had three ganglion cell complex (GCC) and optic nerve head (ONH) scans. In the baseline visit, an extra 3D disc scan was also obtained to register ONH scans of same participant in all visits.

Raw data from all AIGS clinical centers were de-identified and transferred to the Casey Eye Institute OCT Reading Center. Certified graders used RTVue software Version 6.12 to analyze the data and generate disc, NFL, and GCC structural parameters. Scans were excluded if they had low signal strength, cropping artifact, or failed segmentation. Any ONH scan with a signal strength index (SSI) less than 37 and GCC scan less than 42 were excluded for analysis. 22 Measurements from qualified scans in the same visit were averaged.

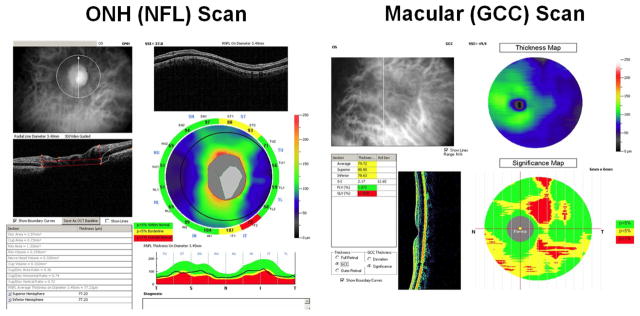

Macular GCC parameters were measured using GCC scans. The macular GCC scan covered a 7 by 7 mm square area, centered 0.75 mm temporal to the fovea, which is designed to improve the coverage of the temporal macula. The macular GCC thickness was defined as the combination of NFL, GCL, and inner plexiform layer. 23 The RTvue software derived a 6 mm diameter GCC thickness map centered 0.75 mm temporal to fovea (Figure 1). Based on the map, overall, superior and inferior hemisphere average of GCC were obtained. Two special pattern analyses parameters were also obtained: a) the global loss volume (GLV), which measures all negative deviation values normalized by the overall map area, and, b) the focal loss volume (FLV), which measures the negative deviation values in areas of significant focal loss in the foveal region.24,25

Figure 1.

Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography scans. Left: optic nerve head (ONH) and peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (NFL) scan. Right: macular ganglion complex (GCC) scan.

Parameters for NFL were measured using ONH scans. The ONH scan covered 4.9mm round area centered at optic disc. It consisted of concentric (1.3–4.9 mm diameter) scans and radial scans (3.4 mm length). The ONH scans were automatically registered with the baseline 3D disc scan. The 3D disc scan also provided the disc margin information. The NFL thickness profile at 3.4 mm diameter was resampled on the NFL map re-centered according to detected optic disc center (figure 1 left). Based on the profile, overall, superior, and inferior quadrant averages of NFL thickness were obtained using the RTVue software. Pattern analysis was applied to the NFL thickness profile using custom software described in a previous publication. 17 The NFL pattern analysis is analogous to the RTVue GCC pattern analysis that generates the GLV and FLV parameters, but based on the NFL profile instead of the GCC map.

Parameters for optic disc were also measured using ONH scans. The ONH scan was processed using RTVue software to delineate cup and disc boundaries (Figure 1). The horizontal cup-to-disc ratio (CDR) is the ratio of the diameter of the cup portion with the total diameter of the optic disc in horizontal direction. The vertical CDR is the ratio in vertical direction. The CDR of area is the ratio of cup area and disc areas.

In summary, the acquired measurements using FD-OCT included (1) the overall, superior and inferior hemisphere averages of the GCC thickness map, (2) the overall, superior and inferior quadrants averages of the NFL thickness profiles, (3) cup disc ratio and rim area, (4) FLV and GLV of GCC thickness map, (5) FLV and GLV of NFL thickness profile.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA) to detect progressive structural loss and visual field progression in PG patients. All tests were two-sided and a p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. The average of three high quality OCT measurements that met the inclusion criteria was used for the statistical analyses. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare means for continuous variables and chi-square test for the categorical variables. When applicable, general estimating equation (GEE) method was used to adjust for correlation between the two eyes of the same patient. 26

The primary analysis used Cox regression9 which is suitable for time-to-event data. The participants had to have at least three follow-up visits in addition to the baseline visit to be eligible for inclusion in the analysis. For each of the covariates in the analysis, we provided a hazard ratio (HR) estimate and the corresponding p-value. We also provided the AUC for the covariate to compare its relative predictive accuracy for glaucomatous progression.

For NFL and GCC parameters, normal, borderline (1–5 percentile of normal population), and abnormal (below 1 percentile) classifications were provided by the RTVue device based on the normative database compiled by Optovue. These classifications are shown in yellow (borderline), red (abnormal), and green (normal) on the RTVue printout (Figure 1). For these categorical covariates, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were produced, and log-rank tests were used to compare risks among categories.

Because many participants had both eyes enrolled in this study, we used a robust sandwich covariance estimation method in the Cox regression to adjust for this potential correlation.

All of the potential covariates were evaluated to build an optimal multivariate Cox regression model through a combination of manual elimination and automatic stepwise selection processes. When the optimal combination of the covariates was determined, the linear form was transformed through a logistic function. The resulting value, which ranged from 0 to 1, was defined as the glaucoma composite progression index (GCPI). The GCPI closer to 1 implied a higher risk of progression.

Results

Characteristics of Participants: Progressors and Non-Progressors

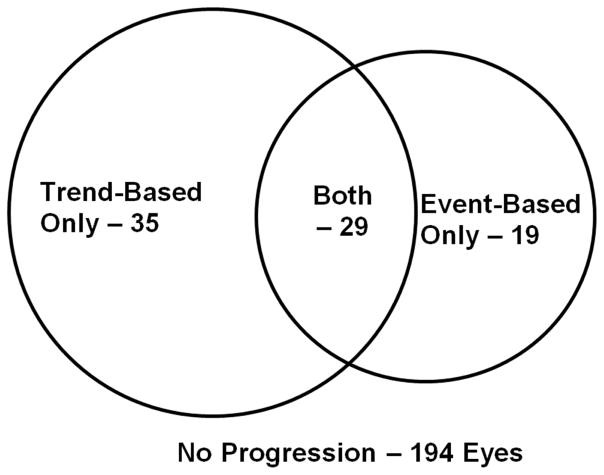

Out of 277 perimetric glaucoma (PG) eyes of 188 participants, there were 194 non-progressor eyes (age 62.2 ± 10.1 years, followed 4.0 ± 1.6 years) from 132 patients and 83 progressor eyes (age 63.8 ± 8.3 years, followed 3.8 ± 1.6 years) from 66 patients (p = 0.61). Out of 5901 total follow-up scans, 289 (4.9%) GCC scans and 307 (5.2%) NFL scans were excluded due to poor signal strength; and 203 (3.4%) GCC and 243 (4.1%) NFL scans were excluded due to cropping artifacts or failed segmentation. More progressors were identified using trend-based analysis rather than event-based analysis (Figure 2). Baseline IOP was slightly lower in progressors, although the difference was not significant (Table 1). The average IOP during the follow-up period was similar (p = 0.13) between non-progressors and progressors (14.1 ± 3.2 vs. 13.5 ± 2.7mmHg). The peak IOP during the follow-up period was similar (p = 0.28) between non-progressors and progressors (16.9 ± 4.6 vs. 16.3 ± 3.9 mmHg. The IOP range during the follow-up period was also similar (p = 0.74) between non-progressors and progressors (5.1 ± 4.2 vs. 5.3 ± 3.8mmHg). Central corneal thickness (CCT), baseline MD, PSD, and VFI were not significantly different between non-progressors and progressors (p > 0.05). The age distribution, sex, and number of patients with African origin, diabetes, systemic hypertension and family history of glaucoma were similar between non-progressor and progressor eyes (Table 1).

Figure 2.

The number of progressing eyes identified using trend-based analysis and event-based analysis

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the participants who had glaucomatous progression compared to the participants who had not experienced progression

| Non-Progressors 194 Eyes | Progressors 83 Eyes | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 62.23 ± 10.08 | 63.75 ± 8.27 | 0.61 |

| Female | 116 ( 59.8% ) | 49 ( 59.0% ) | 0.91 |

| African Origin | 20 ( 10.3% ) | 8 ( 9.6% ) | 0.31 |

| Systemic Hypertension | 72 ( 37.1% ) | 31 ( 37.3% ) | 0.97 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 20 ( 10.3% ) | 11 ( 13.3% ) | 0.48 |

| Family History of Glaucoma | 79 ( 40.7% ) | 44 ( 53.0% ) | 0.61 |

| # Eye Drop Used | 1.4 ± 1.2 | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 0.42 |

| Central Corneal Thickness (μm) | 549 ± 37 | 535 ± 35 | 0.12 |

| IOP at Baseline (mmHg) | 14.6 ± 4.7 | 13.5 ± 3.6 | 0.16 |

| VF Mean Deviation (db) | −4.76 ± 5.13 | −4.99 ± 4.21 | 0.97 |

| VF Pattern Standard Deviation (db) | 5.36 ± 4.02 | 6.61 ± 4.39 | 0.20 |

| VFI (%) | 87.9 ± 15.0 | 86.8 ± 12.5 | 0.92 |

| Follow-up time (years)* | 3.8 ± 2.2 | 3.7 ± 1.9 | 0.72 |

| Fourier-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography Parameters | |||

| Rim Area (mm2) | 0.80 ± 0.38 | 0.69 ± 0.31 | 0.01 |

| CDR, Vertical | 0.80 ± 0.16 | 0.85 ± 0.13 | 0.02 |

| CDR, Horizontal | 0.84 ± 0.15 | 0.85 ± 0.17 | 0.54 |

| CDR, Area | 0.60 ± 0.19 | 0.63 ± 0.19 | 0.27 |

| NFL Overall (μm) | 81.4 ± 12.5 | 78.5 ± 10.7 | 0.19 |

| NFL Inferior Q (μm) | 94.8 ± 19.9 | 88.8 ± 16.3 | 0.15 |

| NFL Superior Q (μm) | 97.6 ± 18.7 | 95.2 ± 18.3 | 0.20 |

| NFL-GLV (%) | 20.24 ± 10.66 | 22.79 ± 8.74 | 0.21 |

| NFL-FLV (%) | 6.79 ± 4.64 | 8.84 ± 4.53 | 0.01 |

| GCC Overall (μm) | 83.9 ± 11.1 | 81.5 ± 9.0 | 0.38 |

| GCC Inferior H (μm) | 81.9 ± 12.9 | 78.1 ± 11.5 | 0.10 |

| GCC Superior H (μm) | 85.8 ± 11.7 | 84.3 ± 10.2 | 0.74 |

| GCC-GLV (%) | 12.91 ± 9.46 | 15.2 ± 7.7 | 0.24 |

| GCC-FLV (%) | 4.75 ± 4.16 | 6.61 ± 4.36 | 0.01 |

Cell contents are mean ± standard deviation. CCT=central corneal thickness; IOP=intraocular pressure; VF= visual field; MD=mean deviation, PSD=pattern standard deviation; VFI=visual field index; CDR=cup-to-disc ratio, Q=quadrant average thickness; H=hemispheric average thickness; NFL=nerve fiber layer; GCC=ganglion cell complex; GLV=global loss volume; FLV=focal loss volume

Follow-up time is calculated over the entire follow-up for the participant.

Among the baseline FD-OCT measurements, the following variables were significantly different between progressors and non-progressors: rim area, vertical CDR, NFL-FLV and GCC-FLV (Table 1). The following variables were not significantly different between progressors and non-progressors: horizontal CDR, NFL overall thickness, NFL inferior and superior quadrant thickness, NFL- GLV, GCC overall thickness, GCC inferior and superior hemisphere thickness and GCC-GLV. According to univariate Cox regression analyses (Table 2), significant baseline risk factors for VF progression include CCT, VF PSD, NFL inferior quadrant thickness, NFL-FLV, GCC overall thickness, GCC inferior hemisphere thickness, GCC-GLV and GCC-FLV. The following baseline factors were not statistically significant: IOP, VFI, rim area, CDRs, NFL overall thickness, NFL superior quadrant thickness, NFL- GLV, GCC overall thickness, and GCC superior hemisphere thickness. The following variables are of borderline statistical significance: VF MD (p = 0.08), NFL-GLV (p = 0.07). Among the significant risk factors, GCC-FLV is the strongest predictor with AUC = 0.632. NFL-FLV is the second strongest with AUC = 0.631, almost identical to GCC-FLV.

Table 2.

Significant Baseline Continuous Variables for Predicting Visual Field Progression

| Unit | HR | P-value | AUC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Corneal Thickness (μm) | 20 μm thinner | 1.14 | 0.012 | 0.621 |

| VF PSD (dB) | 1 db higher | 1.06 | 0.013 | 0.587 |

| Fourier-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography Parameters | ||||

| NFL Inferior Quadrant (μm) | 10 μm thinner | 1.15 | 0.020 | 0.585 |

| NFL-FLV (%) | 5% higher | 1.46 | 0.002 | 0.631 |

| GCC Overall (μm) | 10 μm thinner | 1.29 | 0.013 | 0.576 |

| GCC Inferior Hemisphere (μm) | 10 μm thinner | 1.26 | 0.006 | 0.590 |

| GCC-GLV (%) | 5% higher | 1.18 | 0.003 | 0.597 |

| GCC-FLV (%) | 5% higher | 1.50 | <0.001 | 0.632 |

Univariate Cox regression analysis. HR = Hazard Ratio; AUC = area under receiver-operating curve; VF = visual field; PSD = pattern standard deviation.

Although continuous parameters provide the fullest information, clinicians find it easiest to interpret the classifications of normal, borderline, and abnormal that are simple and highlighted in color in the device printout. Therefore, we calculated hazard ratios for these OCT classifications (Table 3). GCC-FLV was again the strongest predictor of VF progression. Eyes with abnormal GCC-FLV at the baseline had more than 3 times the hazard of significant VF progression compared to those with normal GCC-FLV.

Table 3.

Significant Baseline FD-OCT Categorical Variables for Predicting Visual Field Progression

| Classification | Number of Eyes (%) | Hazard Ratio | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NFL Inferior Quadrant (μm) | Borderline | 28 (10.1%) | 1.18 | 0.33 |

| Abnormal | 86 (31.1%) | 1.25 | 0.04 | |

| NFL-FLV % | Borderline | 55 (19.9%) | 1.50 | 0.17 |

| Abnormal | 108 (39.0%) | 2.07 | 0.007 | |

| GCC Overall | Borderline | 59 (21.3%) | 1.39 | 0.27 |

| Abnormal | 107 (38.6%) | 1.86 | 0.02 | |

| GCC Inferior Hemisphere | Borderline | 37 (13.4%) | 1.52 | 0.21 |

| Abnormal | 135 (48.7%) | 1.88 | 0.007 | |

| GCC-GLV % | Borderline | 63 (22.7%) | 2.05 | 0.04 |

| Abnormal | 123 (46.2%) | 2.31 | 0.003 | |

| GCC-FLV % | Borderline | 34 (12.3%) | 2.69 | 0.007 |

| Abnormal | 149 (53.8%) | 3.07 | <.0001 |

Univariate Cox regression analysis.

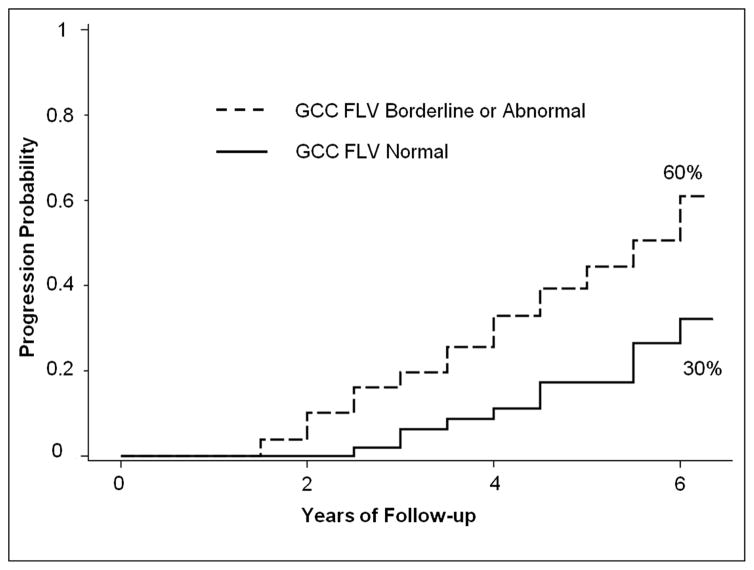

We also calculated the slope of VFI change over time according to GCC-FLV classification at baseline (Table 4). Eyes with normal GCC-FLV at the baseline had, on the average, no change in VFI over time. Eyes with borderline or abnormal GCC-FLV at baseline had significantly faster VFI decline. The slope of VFI deterioration was on the average twice as fast for those with abnormal GCC-FLV at baseline, compared to those with borderline values. . Figure 3 shows the Kaplan-Meier analysis of cumulative probability of visual field progression in a group of PG eyes that had borderline or abnormal GCC-FLV at baseline versus the PG eyes that had normal GCC-FLV at baseline. At 6 years follow-up, eyes with abnormal or borderline GCC-FLV values doubled the risk for VF progression, comparing to eyes with normal GCC-FLV at baseline (Log rank test p <0.001).

Table 4.

Visual Field Progression Rate Stratified by Baseline Ganglion Cell Complex Status

| Baseline GCC-FLV | VFI Slope |

|---|---|

| Normal | −0.03% ± 1.27% (N= 64) |

| Borderline | −0.20% ± 1.03% (N=25) |

| Abnormal | −0.43% ± 1.56% (N=109) |

The visual field index (VFI) slopes are calculated only for eyes with ≥ 6 visits. The rates are significantly (p <0.001) different for the 3 groups stratified by macular ganglion cell complex-focal loss volume (GCC-FLV).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier plot of visual field progression probability in perimetric glaucoma eyes, stratified according to baseline macular ganglion cell complex focal loss volume (GCC FLV) status.

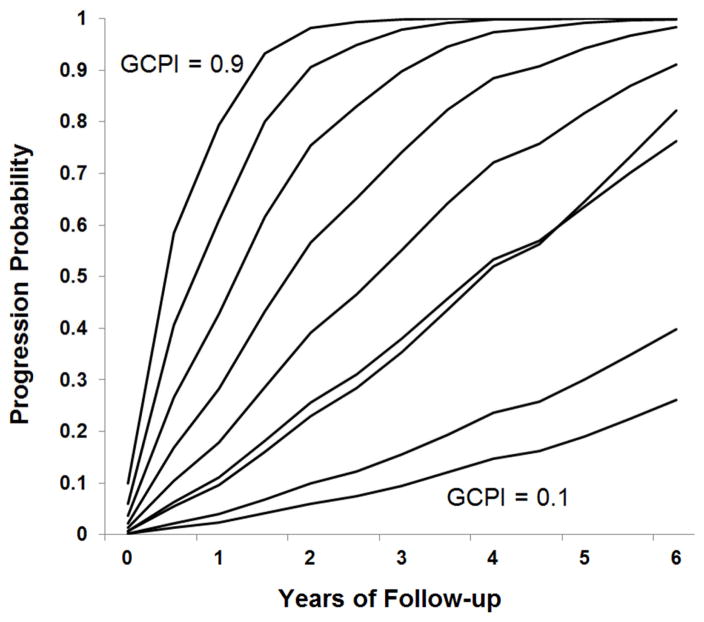

We created the Glaucoma Composite Progression Index (GCPI) by combining the available demographic, clinical, and FD-OCT continuous variables. First, baseline VF, CCT, and FD-OCT parameters with univariate Cox regression HRs at a significance level of p<0.1 were included (Table 2), along with demographic parameters that were different between progressors and non-progressors (Table 1). Next, these candidate covariates were run through an automatic stepwise selection/elimination process, where the p-value for elimination was set at 0.05. The final components that made up the GCPI included age, CCT and GCC-FLV. The components were added together with the optimized weight coefficients (Table 5), and then went through logistic transformation to produce the composite index with a value ranging from 0 to 1. The GPCI AUC of 0.653 performed better than any single variable, including GCC-FLV, which had an AUC of 0.632 (Table 3). The Cox model predicts that the risk of VF progression varies smoothly with GCPI value, with a predicted 6 year progression risk ranging from 0 to 1 for GCPI values from 0.1 to 0.9 (Figure 4).

Table 5.

Glaucoma Composite Progression Index Based on Multivariate Cox Regression Model

| Unit | Coefficient | Hazard Ratio | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 10 years older | 0.21 | 1.24 | 0.047 |

| Central Corneal Thickness | 20 μm thinner | 0.11 | 1.14 | 0.049 |

| GCC-FLV | 5% higher | 0.35 | 1.42 | 0.001 |

The AUC for the Glaucoma Composite Progression Index (GCPI) was 0.653, larger than the AUC for any of the individual variables.

Figure 4.

Probability of visual field progression in perimetric glaucoma eyes stratified according to the Glaucoma Composite Progression Index (GCPI) based on a Cox proportional hazard model = glaucoma composite progression index (range 0.1 to 0.9).

Quartile analysis (Table 6) confirmed that GCPI had significant predictive power for the risk of VF progression (p<0.001, likelihood ratio test) and the rate of VFI decline (p<0.001). Eyes in the lowest quartile had much lower progression risk than the higher three quartiles. The cutoff value of GCPI that maximized the accuracy of predicting progression with sensitivity at 60.2 and specificity at 65.5 was 0.23, which is at the 55% percentile of the study eyes. The speed of progression, as measured by VFI slope, could also be predicted by GCPI (Table 6, p<0.001). Eyes in the bottom quartile of GCPI showed no trend toward progression in the average, while eyes in the top quartile had average VFI progression rate more than twice that of the middle 2 quartiles.

Table 6.

Glaucoma Composite Progression Index Quartile and Risk of Visual Field Progression

| Quartile | GCPI Range | Actual Progression Proportion | VFI Slope* (per year) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0% – 25% | 0.08 – 0.18 | 15.7% | 0.04 ± 1.47 |

| 25% – 50% | 0.18 – 0.22 | 27.5% | −0.25 ± 1.45 |

| 50% – 75% | 0.22 – 0.28 | 37.7% | −0.22 ± 1.32 |

| 75% — 100% | 0.28 – 0.54 | 39.1% | −0.57 ± 1.42 |

Perimetric glaucoma eyes were divided into quartiles according to their Glaucoma Composite Progression Index values.

VFI slope was calculated from eyes with 6 or more visits (N=198)

Discussion

The therapeutic goal for any glaucoma patient is to stabilize the disease and prevent progression of optic nerve damage and visual field loss. The rate of progression over time provides the most definitive guide to treatment decisions. However, longitudinal information is not available for a newly diagnosed glaucoma patient. Therefore methods for using baseline data to stratify the risk of future progression would be most helpful in planning the monitoring frequency and treatment strategy in this situation. Based on the finding from a number of studies, 1–8 clinicians already use IOP and CCT in stratifying the risk and rate of progression. The severity and location of VF damage is also a well-established guide to glaucoma management, based on the logic that evidence of past damage predicts future progression. However, due to the variability of VF performance, a single VF test at the baseline may not be reliable guide. 27,28 Therefore objective tests to establish the severity of optic nerve damage may provide more reliable initial predictors of progression risk.

Measures of focal loss in the peripapillary NFL and macular GCC were the strongest OCT predictors of glaucoma progression in our study. A possible explanation is that focal defects are more reliable indicators of glaucoma damage than overall thinning. An overall thinning of the NFL or GCC could be due to normal population variation, magnification effects (NFL appear thinner in longer eyes), 29,30 myopic retinal degeneration, 31 or aging.32 A focal defect, however, would be highly unlikely in the absence of glaucoma or other specific diseases. In our univariate analysis, several GCC and NFL parameters that measured global average and inferior damage were significant predictors of VF progression. However, NFL-FLV and GCC-FLV were even better predictors as judged by AUC. Multivariable analysis showed that GCC-FLV, the parameter that measures focal loss in the macular ganglion cells, was the only OCT parameter needed in the optimized Glaucoma Composite Progression Index (GCPI) which also included age and the CCT. In clinical practice, it is reasonable to assume that most clinicians would not have the facility to compute the GCPI. However, clinicians could look at the GCC-FLV classification alone for the simplest strong predictor. Eyes with baseline GCC-FLV classification as borderline or abnormal have a hazard ratio of ~3 in our Cox model, and a doubling of VF progression rate to 60% over an average follow-up period of 4 years in our study population.

An interesting finding (Tables 2 and 3) is that GCC seems more robust than NFL in predicting progression. In particular, decreased inferior hemispheric GCC thickness average carried stronger relative risk than decreased inferior quadrant NFL thickness. One possible reason is that GCC is measured in the macular area that fall within the 24-2 VF, while the peripapillary NFL supplies the entire retina, some of which fall outside the VF testing area and therefore may not correlate as well. Another possible reason is that NFL is more susceptible to decentration error. The thickness of NFL is approximately inversely proportional to the radial distance from disc center.29 Therefore decentration error could bias the measurement of NFL thickness in a quadrant (i.e. a superiorly decentered sampling circle would artifactually increase the inferior NFL thickness and decrease the superior NFL thickness). The decentration-related error is relatively significant for a quadrantic measurement of NFL thickness because the sampling circle is relatively small (3.4 mm diameter). Furthermore, the center of the disc is difficult to establish accurately due to anatomic variations (shape variation, tilt, peripapilary atrophy, etc.) On the other hand, the GCC thickness varies slowly outside parafoveal region, and the GCC analytic area (6 mm circle) is relatively large compared to parafoveal area. Furthermore, the centration of the GCC scan is easily established relative to foveal fixation. Therefore hemispheric GCC thickness parameters are relatively robust to decentration error.

In a recent publication, we had analyzed the baseline OCT parameters that predicted development glaucomatous VF defects (converting to perimetric glaucoma) in the glaucoma suspects and pre-perimetric glaucoma cohort of the AIG Study.17 We found that GCC-FLV was also the most powerful predictor converting to perimetric glaucoma. More baseline OCT parameters, including NFL, GCC, and disc parameters, were significant predictors of conversion. And the AUC values were generally higher for predicting conversion, with the AUC of GCC-FLV at 0.753. This compares with an AUC of 0.632 for prediction progression with the same parameter in this paper. The comparison suggests that OCT assessment may be most powerful in the earliest stages of glaucoma.

Several prior studies have looked at ocular hypertensives or glaucoma suspects and the role of imaging at baseline to predict conversion to glaucoma. Abnormal baseline measurements using confocal scanning laser ophthalmoloscope (cSLO) scans33, scanning laser polarimetry34, and NFL thickness with OCT35 have all been shown to predict glaucomatous visual field change in ocular hypertensive glaucoma suspects. In a report analysing early data from the AIG Study with time-domain OCT, scanning laser polarimetry and cSLO, abnormal baseline ONH topography and thin inferior retinal NFL were reported to be predictive of VF progression in a smaller sample of glaucoma suspects and patients.36 These studies showed that NFL loss as measured by advanced imaging modalities could be used to predict future VF conversion.

The importance of the focal macular structural parameter in predicting visual field progression in our analysis suggests that macular damage may be more common and occur earlier than previously believed. It has recently been shown that macula GCC parameters measured with OCT can be used to measure the glaucomatous damage in the macula.37 Studies have also shown that FLV and GLV demonstrate a higher diagnostic accuracy than average GCC thickness.24,38 In a retrospective study, baseline macular GCC thickness of the inferior hemifield was shown to be predictive of VF progression in POAG39 . Interestingly, Sung et al. also proposed that in advanced glaucoma, changes in average macula thickness measured with spectral domain OCT may improve the ability to detect progression.40 This is also supported by recent literature that showed more than 50% of eyes with mild to moderate glaucoma have field loss within the central 3 degrees, when tested using the 10-2 central VF algorithm.41 However, it is a significant time burden to conduct routine 10-2 VF testing in addition to the standard 24-2 VF testing in the clinical practice of glaucoma. Macular GCC mapping (or other types of ganglion cell related mapping) by OCT is faster and may be a more practical way of evaluating glaucoma damage in the central regions.

Our multivariate Cox analysis showed age and CCT to be synergistic with GCC-FLV in predicting progression. Age is a well-known factor associated with both the higher prevalence of glaucoma1,8 as well as faster progression.3,4 CCT has been established as a significant risk factor for glaucoma in a population-base study42 and for glaucoma conversion in ocular hypertensives.8 Therefore it is not surprising that age and CCT are significant independent risk factors included in the GCPI in the current study. What is more interesting is that IOP and VF parameters were not found to be significant in the multivariate analysis. While a considerable body of evidence supports the role of IOP as a strong predictor of VF progression,2,6 this association may have been masked in our study by the use of pressure-lowering glaucoma eye drops. Due to ethical considerations, it was not possible to randomize treatment in the AIG study nor blind the treating physicians to IOP measurements. Therefore IOP values in both progressors and non-progressors groups were well controlled throughout the study. The lack of eyes with untreated high IOP took away the contrast necessary for the study to detect any IOP effect. Finally, since physicians were allowed to treat according to their clinical judgment and current practice in the study, different patterns of care depending on cornea thickness as well might also have had an impact on our results. VF parameters, on the other hand, offered a wide range of contrast in our study population. Furthermore, VF PSD was found to a significant univariate predictor of progression, as would be expected from past studies.3 The fact that all VF parameters dropped out in the multivariate analysis suggests that GCC-FLV was a more reliable measure of glaucoma damage, therefore VF parameters became redundant when these parameters were analyzed together.

In the present study, optic nerve rim area at baseline was not a statistically significant predictor of future field progression. Studies have not consistently shown a clear association between rim area and VF change.36,43,44 However, it has been suggested that optic disc topography analysis based on identification of Bruch’s membrane opening-minimum rim width showed good correlation with VF sensitivities, therefore supporting the role of this parameter as a strong predictor of VF change.45 The integration of new algorithms in disc topography analysis with OCT may improve the diagnostic abilities of this parameter.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that, in a large cohort of perimetric glaucoma patients followed for 1.5 to 6.5 years, FD-OCT measurements of peripapillary NFL and macular GCC are significant predictors of VF progression, in addition to known risk factors of age and CCT. GCC-FLV was the most significant predictive factor in multivariate Cox analysis. The Glaucoma Composite Prediction Index (GCPI) calculated from 3 most important risk factors - age, CCT, and GCC-FLV - increased the accuracy of predicting progression compared to any single factor. It has predictive value in terms of both risk of significant VF progression and rate of VFI change over time. These parameters may be useful in the baseline evaluation of glaucoma and initial determination of relative progression risk, which is relevant to the the planning of treatment intensity (i.e. setting target IOP) and follow-up frequency. However, the absolute predictive accuracy of these baseline factors are not high and there is room for further improvement in the development of novel predictive measurements. Baseline factors are indicators of disease severity. Greater disease severity could be due to faster disease progression, but could also be due to great disease duration. Therefore a baseline measurement alone can never be a very accurate predictor of progression, and longitudinal monitoring is always needed to establish the rate of disease progression. Furthermore, patient risk factors can change over time, and the risk assessment is likely to require continual updates and follow-on longitudinal analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support

Supported by NIH grants R01 EY013516, R01 EY023285 (Bethesda, MD),

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov information: Identifier: NCT01314326; Responsible party: David Huang, Oregon Health and Science University; Official title: Advanced Imaging for Glaucoma Study

Financial Disclosure

Dr. Huang and Dr. Tan have a significant financial interest in Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc (Dublin, CA). Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU, Portland, OR), Dr. Huang and Dr. Tan have a significant financial interest in Optovue, Inc. (Fremont, CA), a company that may have a commercial interest in the results of this research and technology. These potential conflicts of interest have been reviewed and managed by OHSU. Dr. Huang and Dr. Schuman receive royalties for an optical coherence tomography patent owned and licensed by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Cambridge, MA) and Massachusetts Eye & Ear Infirmary to Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc. Dr. Greenfield receives research support from Optovue, Inc., Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., and Heidelberg Engineering (Carlsbad, CA). Dr. Varma has received research grants, honoraria and/or travel support from Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Heidelberg Engineering, and Optovue, Inc. Dr. Chopra is a consultant to Allergan, Inc. Dr. Zhang, Dr. Francis and Dr. Dastiridou have no financial interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Quigley HA, Enger C, Katz J, et al. Risk factors for the development of glaucomatous visual field loss in ocular hypertension. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:644–649. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090170088028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration.The AGIS Investigators. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130(4):429–440. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00538-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leske MC, Heijl A, Hussein M, Bengtsson B, Hyman L, Komaroff E. Factors for glaucoma progression and the effect of treatment: the early manifest glaucoma trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121(1):48–56. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nouri-Mahdavi K, Hoffman D, Coleman AL, et al. Predictive factors for glaucomatous visual field progression in the Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(9):1627–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caprioli J, Coleman AL. Intraocular pressure fluctuation a risk factor for visual field progression at low intraocular pressures in the advanced glaucoma intervention study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(7):1123–1129. e1123. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medeiros FA, Sample PA, Zangwill LM, Bowd C, Aihara M, Weinreb RN. Corneal thickness as a risk factor for visual field loss in patients with preperimetric glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136(5):805–813. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00484-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medeiros FA, Sample PA, Weinreb RN. Corneal thickness measurements and frequency doubling technology perimetry abnormalities in ocular hypertensive eyes. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(10):1903–1908. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00734-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon MO, Beiser JA, Brandt JD, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: baseline factors that predict the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(6):714–720. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.6.714. discussion 829–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medeiros FA, Weinreb RN, Sample PA, et al. Validation of a predictive model to estimate the risk of conversion from ocular hypertension to glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(10):1351–1360. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.10.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasker MT, van den Enden A, Bakker D, Hoyng PF. Deterioration of visual fields in patients with glaucoma with and without optic disc hemorrhages. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115(10):1257–1262. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100160427006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Budenz DL, Anderson DR, Feuer WJ, et al. Detection and prognostic significance of optic disc hemorrhages during the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(12):2137–2143. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zangwill LM, Weinreb RN, Beiser JA, et al. Baseline topographic optic disc measurements are associated with the development of primary open-angle glaucoma: the Confocal Scanning Laser Ophthalmoscopy Ancillary Study to the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(9):1188–1197. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.9.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sung VC, Koppens JM, Vernon SA, et al. Longitudinal glaucoma screening for siblings of patients with primary open angle glaucoma: the Nottingham Family Glaucoma Screening Study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(1):59–63. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.072751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tielsch JM, Katz J, Sommer A, Quigley HA, Javitt JC. Family history and risk of primary open angle glaucoma. The Baltimore Eye Survey. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112(1):69–73. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090130079022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ernest PJ, Schouten JS, Beckers HJ, Hendrikse F, Prins MH, Webers CA. An evidence-based review of prognostic factors for glaucomatous visual field progression. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(3):512–519. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Read RM, Spaeth GL. The practical clinical appraisal of the optic disc in glaucoma: the natural history of cup progression and some specific disc-field correlations. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1974;78(2):OP255–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X, Loewen N, Tan O, et al. Predicting Development of Glaucomatous Visual Field Conversion Using Baseline Fourier-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 163:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mujat M, Chan R, Cense B, et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness map determined from optical coherence tomography images. Opt Express. 2005;13(23):9480–9491. doi: 10.1364/opex.13.009480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gabriele ML, Wollstein G, Ishikawa H, et al. Three dimensional optical coherence tomography imaging: advantages and advances. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010;29(6):556–579. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le PV, Zhang X, Francis BA, et al. Advanced imaging for glaucoma study: design, baseline characteristics, and inter-site comparison. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159(2):393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.11.010. e392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bengtsson B, Heijl A. A visual field index for calculation of glaucoma rate of progression. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145(2):343–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X, Iverson SM, Tan O, Huang D. Effect of Signal Intensity on Measurement of Ganglion Cell Complex and Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Scans in Fourier-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2015;4(5):7. doi: 10.1167/tvst.4.5.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan O, Li G, Lu AT, Varma R, Huang D. Mapping of macular substructures with optical coherence tomography for glaucoma diagnosis. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(6):949–956. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan O, Chopra V, Lu AT, et al. Detection of macular ganglion cell loss in glaucoma by Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(12):2305–2314. e2301–2302. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sehi M, Goharian I, Konduru R, et al. Retinal blood flow in glaucomatous eyes with single-hemifield damage. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(3):750–758. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42(1):121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song C, De Moraes CG, Forchheimer I, Prata TS, Ritch R, Liebmann JM. Risk calculation variability over time in ocular hypertensive subjects. J Glaucoma. 2014;23(1):1–4. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31825af795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chauhan BC, Garway-Heath DF, Goni FJ, et al. Practical recommendations for measuring rates of visual field change in glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92(4):569–573. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.135012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang D, Chopra V, Lu AT, Tan O, Francis B, Varma R. Does optic nerve head size variation affect circumpapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measurement by optical coherence tomography? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(8):4990–4997. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Savini G, Barboni P, Parisi V, Carbonelli M. The influence of axial length on retinal nerve fibre layer thickness and optic-disc size measurements by spectral-domain OCT. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(1):57–61. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2010.196782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akashi A, Kanamori A, Ueda K, Inoue Y, Yamada Y, Nakamura M. The Ability of SD-OCT to Differentiate Early Glaucoma With High Myopia From Highly Myopic Controls and Nonhighly Myopic Controls. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(11):6573–6580. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xinbo Zhang BF, Dastiridou Anna, et al. Longitudinal and Cross-Sectional Analyses of Age Effects on Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer and Ganglion Cell Complex Thickness by Fourier-Domain OCT. TVST. 2016 doi: 10.1167/tvst.5.2.1. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strouthidis NG, Gardiner SK, Owen VM, Zuniga C, Garway-Heath DF. Predicting progression to glaucoma in ocular hypertensive patients. J Glaucoma. 2010;19(5):304–309. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3181b6e5a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohammadi K, Bowd C, Weinreb RN, Medeiros FA, Sample PA, Zangwill LM. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measurements with scanning laser polarimetry predict glaucomatous visual field loss. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138(4):592–601. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lalezary M, Medeiros FA, Weinreb RN, et al. Baseline optical coherence tomography predicts the development of glaucomatous change in glaucoma suspects. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142(4):576–582. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sehi M, Bhardwaj N, Chung YS, Greenfield DS. Evaluation of baseline structural factors for predicting glaucomatous visual-field progression using optical coherence tomography, scanning laser polarimetry and confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy. Eye (Lond) 2012;26(12):1527–1535. doi: 10.1038/eye.2012.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hood DC, Raza AS, de Moraes CG, Liebmann JM, Ritch R. Glaucomatous damage of the macula. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2013;32:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim NR, Lee ES, Seong GJ, Kim JH, An HG, Kim CY. Structure-function relationship and diagnostic value of macular ganglion cell complex measurement using Fourier-domain OCT in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(9):4646–4651. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-5053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anraku A, Enomoto N, Takeyama A, Ito H, Tomita G. Baseline thickness of macular ganglion cell complex predicts progression of visual field loss. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;252(1):109–115. doi: 10.1007/s00417-013-2527-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sung KR, Sun JH, Na JH, Lee JY, Lee Y. Progression detection capability of macular thickness in advanced glaucomatous eyes. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(2):308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schiefer U, Papageorgiou E, Sample PA, et al. Spatial pattern of glaucomatous visual field loss obtained with regionally condensed stimulus arrangements. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(11):5685–5689. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-5067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Francis BA, Varma R, Chopra V, Lai MY, Shtir C, Azen SP. Intraocular pressure, central corneal thickness, and prevalence of open-angle glaucoma: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146(5):741–746. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suda K, Hangai M, Akagi T, et al. Comparison of Longitudinal Changes in Functional and Structural Measures for Evaluating Progression of Glaucomatous Optic Neuropathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(9):5477–5484. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-16704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leung CK, Liu S, Weinreb RN, et al. Evaluation of retinal nerve fiber layer progression in glaucoma a prospective analysis with neuroretinal rim and visual field progression. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(8):1551–1557. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muth DR, Hirneiss CW. Structure-Function Relationship Between Bruch's Membrane Opening-Based Optic Nerve Head Parameters and Visual Field Defects in Glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(5):3320–3328. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.