SUMMARY

It is well recognized that, GPCRs can activate Ras-regulated kinase pathways to produce lasting changes in neuronal function. Mechanisms by which GPCRs transduce these signals and their relevance to brain disorders are not well understood. Here we identified a major Ras regulator, neurofibromin 1 (NF1), as a direct effector of GPCR signaling via Gβγ subunits in the striatum. We found that binding of Gβγ to NF1 inhibited its ability to inactivate Ras. Deletion of NF1 in striatal neurons prevented the opioid receptor induced activation of Ras and eliminated its coupling to Akt-mTOR signaling pathway. By acting in the striatal medium spiny neurons of the direct pathway, NF1 regulates opioid induced changes in Ras activity thereby sensitizing mice to psychomotor and rewarding effects of morphine. These results delineate a novel mechanism of GPCR signaling to Ras pathways and establish a critical role of NF1 in opioid addiction.

INTRODUCTION

Neural circuits rely on the neurotransmitter signaling systems for processing information flow that ultimately drives behavioral reactions. As a central input nucleus of the basal ganglia system, the striatum is crucially involved in initiating and maintaining movement, formation of habits, valuation of reward and mediating the effects of addictive drugs [1, 2]. The striatum receives diverse and abundant neurotransmitter inputs from multiple brain regions, which converge on medium spiny projection neurons (MSN), a major cell type in the region. Many of these inputs mediate their effects by activating G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) abundantly expressed by MSNs [3]. GPCRs transduce their signals via a conserved mechanism dissociating heterotrimeric G proteins into Gα and Gβγ subunits, which in turn regulate downstream “effector” molecules [4]. It is thought that neurotransmitter-bound GPCRs activate distinct effectors that lead to unique physiological adaptations in MSNs and impose on behavior by producing lasting changes in the properties of striatal circuits [2]. However, the molecular and cellular mechanisms by which striatal GPCRs induce these changes are not well understood.

Several striatal GPCRs are capable of activating kinase pathways typically involved in cellular differentiation, growth, proliferation and survival (e.g. Akt, mTOR and MAPK) and this signaling is known to play a crucial role in regulating multiple aspects of striatal physiology including excitability, synaptic plasticity and spine architecture [5, 6]. Several “transactivation” mechanisms have been proposed to link GPCR activation with modulation of kinase pathways, and have illustrated important roles for Gβγ and Ras in this process [7–9]. The activity of Ras is controlled by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs), which stimulate the exchange of GDP for GTP, and by GTPase activating proteins (GAPs), which terminate the active state by stimulating GTP hydrolysis [10]. In the active GTP-bound state, Ras binds effectors (e.g., Raf and PI3K) to activate downstream signaling cascades (i.e. MAPK-ERK1/2 and Akt-mTOR). Both GEFs and GAPs are multidomain proteins and are subject to regulation by extracellular signals to allow for changes in Ras activity in response to changes in the environment [10]. Neurotransmitter controlled regulation of Ras activity is essential for neuronal physiology and its disruption underlies many neuropsychiatric conditions [5, 6].

Striatal function is substantially modulated by the opioid system [11, 12]. Striatal neurons express endogenous opioid peptides, endorphins, enkephalins and dynorphin, that exert their effects by acting on GPCRs μ-, δ- and κ-opioid receptors (MORs, DORs and KORs), respectively [13]. As the target for exogenous opiate morphine, MOR plays a central role in controlling reward behavior, nociception and development of dependence [11, 12]. Activation of MOR is known to indirectly affect striatal physiology, by disinhibiting dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area that send their projections to the ventral striatum, thereby increasing dopaminergic tone [11, 12]. Notably, MORs are also prominently expressed in MSNs [14, 15], and recent evidence indicates that direct action of MOR in the striatum plays a pivotal role in opioid-mediated reward behavior [16]. Activation of MOR by morphine and/or endogenous opioid peptides markedly affects neuronal physiology, inducing changes in synaptic plasticity, dendritic spine morphology and intrinsic excitability [17, 18]. Many of these long-term changes in physiology require signaling to Ras and its downstream kinase pathways [19]. Indeed, morphine markedly regulates multiple kinase pathways downstream from Ras, and this coupling is thought to contribute to the lasting nature of changes induced by exposure to opioids [20, 21]. However, the molecular mechanisms of Ras activation by opioid receptors in the striatal neurons and behavioral implications of this process remain obscure.

In this study we identified a novel mechanism for the Ras activation by GPCRs, operating in the striatal neurons. Specifically, we found that Gβγ subunits when released upon activation of MOR, bind and inhibit the activity of key Ras GAP protein neurofibromin (NF1) thereby leading to Ras activation. Elimination of NF1 completely prevented the ability of morphine to activate Ras and downstream Akt-mTOR/GSK3β signaling pathway in the striatum. Furthermore, mice with disruption of striatal NF1 showed blunted responses to rewarding but not analgesic properties of morphine. These results reveal critical role for NF1 in coupling neuronal GPCR signaling to Ras and suggest important implications of this process in the striatum for understanding drug addiction.

RESULTS

NF1 is a novel G protein effector regulated by μ-opioid receptor signaling

We hypothesized that the regulation of Ras by opioid receptors in the striatum may involve modulation of proteins, which directly control Ras activity. Among several known GEFs and GAPs regulating Ras activity, we found NF1 to be prominently expressed in the striatum. Fluorescence in situ hybridizations revealed high levels of NF1 to be present in most striatal neurons. Furthermore, all neurons containing μ-opioid receptor (MOR), also co-expressed NF1 (Supplementary Figure 1A,B).

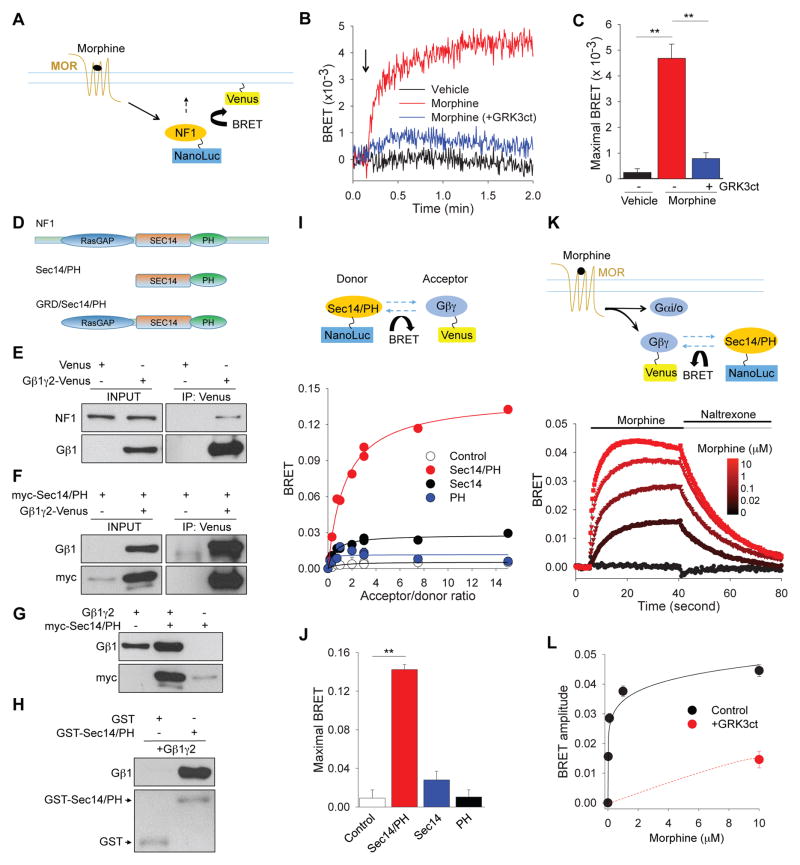

To begin probing potential involvement of NF1 in opioid signaling, we first examined whether NF1 is sensitive to changes in the activity of MOR. HEK293 cells expressing Venus-based plasma membrane reporter construct were transfected with MOR and luciferase-tagged NF1 and changes in bioluminescence energy transfer (BRET) were used to monitor changes in the proximity of NF1 to the plasma membrane (Figure 1A). The stimulation of cells with morphine resulted in a rapid increase in BRET signal (1/τ = 0.23 ± 0.05 s−1), suggesting NF1 recruitment to the plasma membrane (Figure 1B). Interestingly, a blockade of G protein βγ subunits with inhibitory peptide derived from GRK3, completely prevented NF1 translocation, suggesting that it is mediated by Gβγ (Figure 1B,C). Analysis of NF1 amino acid sequence revealed the presence of a bipartite module composed of a Sec14 homologous segment and a pleckstrin homology (PH)-like domain immediately adjacent to the RasGAP domain (Figure 1D). Since both PH and Sec14 domains have been shown to interact with Gβγ [22, 23], we next investigated the ability of NF1 to form complexes with Gβγ. First, we found that Gβγ and endogenous, full-length NF1 co-immunoprecipitated following Gβγ overexpression in HEK293T cells (Figure 1E). Second, the Sec14/PH module was sufficient for interaction with Gβγ in transfected cells (Figure 1F). Third, co-expression of Sec14/PH and Gβγincreased each other levels, suggesting that binding between these two proteins is mutually stabilizing (Figure 1G). Finally, we demonstrated that a GST-tagged recombinant Sec14/PH protein immobilized on beads could pull-down purified recombinant Gβγ, indicating that the binding between the Sec14/PH module and Gβγ is direct (Figure 1H). We further confirmed specificity of Gβγ-NF1 interaction by showing that a dominant negative construct (NF1-DN) comprising the minimal binding site (Sec14/PH) for Gβγ binding prevented association between Gβγ and full-length endogenous NF1 (Supplementary Figure 1C).

Figure 1. NF1 is a novel G protein effector downstream from MORs activation.

(A) Schematic of the assay design to study membrane recruitment of NF1 in response to MOR activation. Association of NanoLuc-tagged NF1 with membrane targeted Venus is expected to result in BRET signal. (B) Real time kinetics of BRET signal change upon NF1 plasma membrane recruitment. Arrow indicates time of morphine application. (C) Quantification of maximal amplitude of BRET signals from 3 independent experiments. **p<0.01, One-Way ANOVA post hoc Tukey’s test. (D) Schematic representation of NF1 domain composition and truncation mutants used in this study. (E) Co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous NF1 with over-expressed Gβ1γ2 complex in transfected HEK293T cells. (F) Co-immunoprecipitation of Sec14/PH module with Gβ1γ2 complex in transfected HEK293T cells. (G) Mutual stabilization of Sec14/PH module and Gβ1γ2 upon co-expression in HEK293T cells. (H) Direct interaction between purified recombinant Sec14/PH and Gβ1γ2 proteins studied in pull-down assays. (I) Upper, Schematic diagram of BRET strategy to study NF1-Gβγ interaction in living cells. Lower, Analysis of Gβγ binding to NF1 constructs by titrating ratios of interacting partners. (J) Quantification of maximal BRET ratios generated by various NF1 constructs from three independent experiments. **p<0.01, One-Way ANOVA post hoc Tukey’s test. (K) Upper: Schematic representation of the BRET assay monitoring interaction between Sec14/PH and Gβγ upon MORs activation and inactivation. Lower: Real-time kinetics of BRET signal in response to changes in MOR activity. (L) Quantification of the dose-response relationship of Gβγ-NF1 interaction from 3 independent experiments. Gβγ scavenger GRK3ct blunted the BRET response between Sec14/PH module and Gβγ. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S1.

In order to probe for Gβγ-Sec14/PH interaction in living cells, we measured BRET between Sec14/PH module and Gβγ (Figure 1I). Titration experiments revealed a hyperbolic increase in BRET signal that rapidly saturated with an increase in the acceptor/donor ratio (Figure 1I,J). In contrast, no significant increase in the BRET signal was observed when either Sec14 or PH domains were expressed independently. Since Sec14 and PH domains of NF1 are tightly integrated [24], we conclude that the Sec14/PH module of NF1 forms a novel molecular entity for the specific interaction with Gβγ.

Typically, Gβγ subunits are unable to interact with effector molecules (e.g. NF1) in their inactive state, due to occlusion of the effector-binding interface by the Gα subunits in the heterotrimer complex. Activation of GPCR by agonists promotes binding of GTP to α subunits, leading to dissociation of the heterotrimer and release of the Gβγ subunits. Upon termination of GPCR activation, Gα subunit hydrolyses GTP and then re-associates with Gβγ subunits. Therefore, we examined whether Gβγ-Sec14/PH interaction can be regulated by GPCR activity by measuring real time changes in the BRET signal upon MORs activation/deactivation (Figure 1K). Stimulation of MORs with increasing concentrations of morphine led to a progressive increase in amplitude of BRET response. Conversely, inactivation of MORs with the antagonist naltrexone rapidly quenched the signal (Figure 1K). Furthermore, the speed of the signal transfer between Gβγ and NF1 (1/τ = 0.67 ± 0.05 s−1) matched kinetics of G protein activation and NF1 membrane recruitment (Figure 1B). Dose-response studies revealed an EC50 value of 40 ± 10 nM for morphine induced BRET signal between Gβγ and NF1 pair (Figure 1L), which is in close agreement with EC50 of G protein activation by MOR studied by GTPγS binding [25]. Notably, the signal transfer was blocked by the Gβγ scavenger GRK3ct, indicating a specific nature of the binding (Figure 1L). A similar blockade was also seen with NF1 dominant negative construct (Supplementary Figure 1D–F). Finally, overexpression of NF1 in HEK293 cells did not abolish ERK phosphorylation upon activation of MOR, yet significantly diminished it (Supplementary Figure 1G,H), again indicating that NF1 is involved in transduction of MOR signals. In summary, these data indicate that Gβγ subunits bind specifically and directly to Sec14/PH module of NF1 and that this interaction is dynamically modulated by changes in the activity of MOR.

Gβγ inhibits NF1-mediated inactivation of Ras

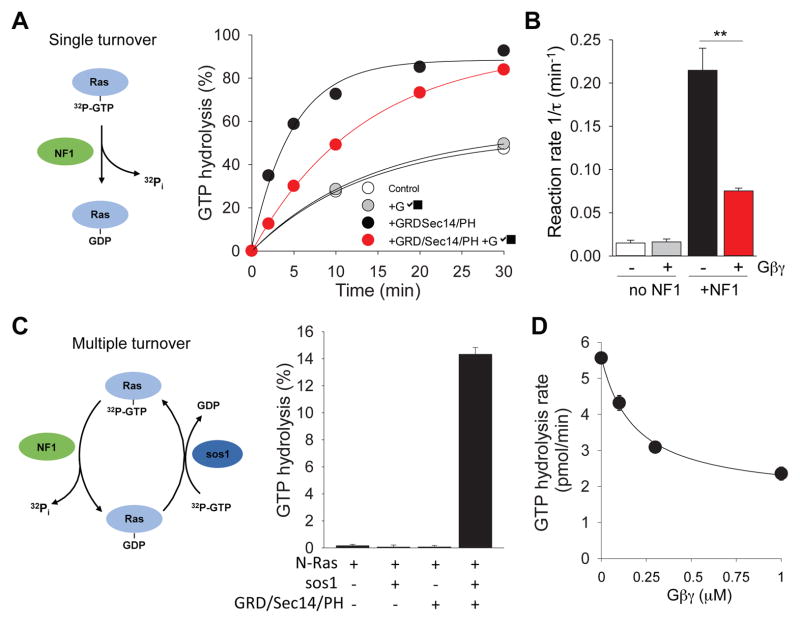

We next analyzed the functional consequences of Gβγ binding to NF1. As a GAP protein, NF1 utilizes its conserved GAP-related domain (GRD) to accelerate GTPase activity of Ras. Interestingly, the GRD module is located in the immediate vicinity of Sec14/PH module (Figure 1D). Thus, we studied the GAP activity of the GRD/Sec14/PH fragment towards Ras in the in vitro system with purified recombinant proteins in the presence or absence of Gβγ (Figure 2). Under single turnover conditions, the addition of the GRD/Sec14/PH module greatly accelerated GTP hydrolysis on Ras. The time constant of the reaction increased from 0.015 ± 0.003 min−1 to 0.215 ± 0.025 min−1 (Figure 2A,B). Gβγ significantly inhibited the NF1’s GAP activity but had no effect on the rate of basal GTP hydrolysis by Ras in the absence of NF1.

Figure 2. Gβγ inhibits GTPase accelerating protein (GAP) activity of NF1.

(A) Left, Diagram of single turnover principle of Ras GTP hydrolysis assay. Right, Effects of recombinant Gβγ on NF1 fragment (GRD/Sec14/PH)-stimulated GTPase activity of N-Ras. (B) Quantification of the effect of Gβγ on GTPase activity of NF1. (C) Left, Diagram of multiple turnover of Ras GTP hydrolysis assay principle. The assay involves both GAP (NF1) and GEF (sos1). Right, Both RasGEF and RasGAP are necessary for Ras GTP hydrolysis in the multiple turnover assay. (D) Gβγ inhibits Ras GTP hydrolysis rate in dose-dependent manner with IC50 for Gβγ of 0.187 ± 0.044 μM. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

To obtain further insight into the inhibitory action of Gβγ, we next performed an assay under multiple turnover conditions that more closely reflect the physiological setting. In this assay system we introduced GEF protein Sos1 for the Ras to undergo multiple activation/deactivation cycles (Figure 2C). Again, Gβγ markedly inhibited acceleration in steady-state Ras GTPase activity mediated by the GRD/Sec14/PH module causing approximately 2.5-fold inhibition (from 5.56 ± 0.13 pmol/min to 2.35 ± 0.17 pmol/min) (Figure 2D). This inhibitory effect was dose-dependent and showed saturation. Together, these results indicate that Gβγ binding to NF1 potently inhibits its GAP activity towards Ras.

NF1 is necessary for μ-opioid receptor coupling to Ras activation in striatal medium spiny neurons

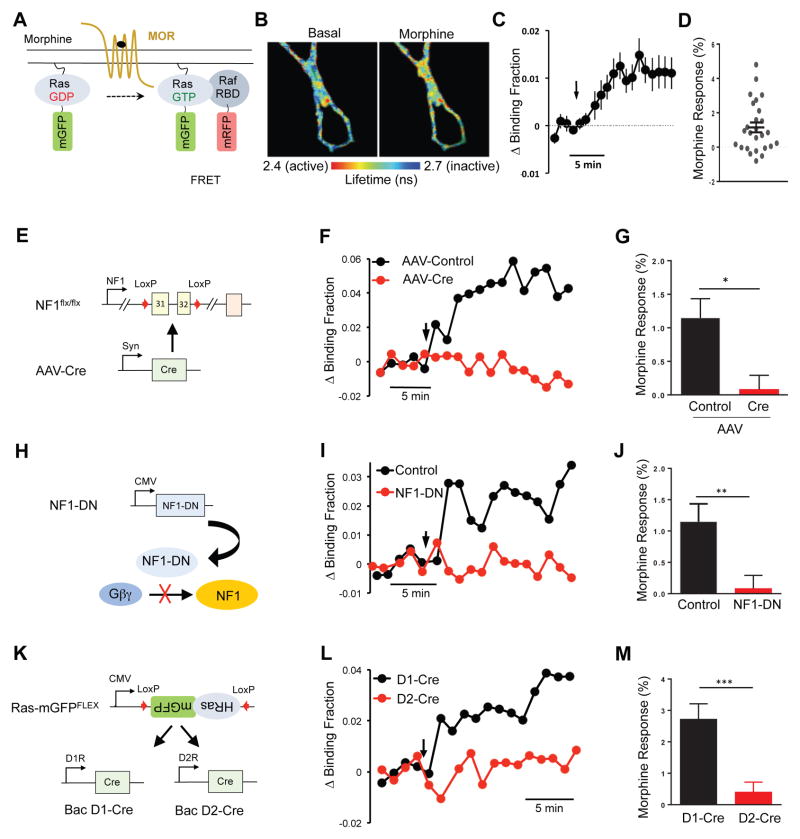

In order to study the role of NF1 in transmission of MOR signals in the native environment, we examined the contribution of NF1 to Ras activation by morphine in cultured striatal medium spiny neurons (MSNs). We monitored Ras activation by utilizing fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) - Forster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) approach (Figure 3A) that uses optical sensors to detect changes in Ras activity in real time. Application of morphine resulted in a readily detectable increase in the FLIM-FRET signal in cultured MSNs, indicative of Ras activation (Figure 3B). Ras activity rapidly increased and reached a steady-state plateau in ~5 minutes (Figure 3C). Consistent with the observation that MOR is not expressed in all striatal neurons (Supplementary Figure 1A,B), we found that morphine elicited a significant response in approximately half of neurons (11 out of 26 examined; Figure 3D). Using this system, we first analyzed consequences of NF1 ablation. Infection of cultured striatal neurons from conditional NF1flx/flx mice with AAV-Cre (Figure 3E) resulted in a substantial reduction of the NF1 protein expression level compared to cultures treated with the control AAV virus (Supplementary Figure 2A). Remarkably, we detected no significant Ras activation in response to morphine in cultures where NF1 was deleted by AAV-Cre treatment (Figure 3F,G). In contrast, treatment of MSNs with AAV-Cre did not significantly affect the response to BDNF stimulation (Supplementary Figure 2B–D), which is known to transduce the signal by activating Ras through GEF proteins. This indicates that deletion of NF1 specifically abolished coupling of MOR to Ras, while preserving the ability of Ras to be activated by receptor tyrosine kinases.

Figure 3. NF1 is essential for Ras activation by MORs in cultured striatal medium spiny neurons (MSNs).

(A) Schematic of Ras FLIM-FRET sensor. Increase in binding between mGFP-RasGTP and mRFP-Raf-RBD upon Ras activation is measured as a decrease in GFP fluorescence lifetime and quantified as change in binding fraction. (B) Representative fluorescence lifetime image of striatal MSNs before and 10 minutes after 10 μM morphine application. Warmer colors indicate decrease in lifetime, which corresponds to higher Ras activity. (C) Average time course of Ras activation (change in binding fraction) of MSNs in response to 10 μM morphine application (black arrow). Average includes neurons, which responded and those that showed no response to morphine. (D) Morphine induced Ras activation of individual MSNs. (E) Schematic of conditional Nf1 ablation strategy in cultured MSNs. Cultured MSNs from neonatal Nf1flx/flx mice were infected with AAV-Cre to induce Nf1 elimination. (F) Representative time course of Ras activation (change in binding fraction) in response to morphine application (black arrow) in WT (AAV-Control) and Nf1 cKO (AAV-Cre) MSNs. (G) Quantification of Ras response to morphine in control and Nf1 cKO (Cre) cultures. Unpaired t test *p=0.02, n=26, 15. (H) Schematic of strategy to prevent Gβγ binding to NF1 by expressing the minimal binding module of NF1 (NF1-DN). (I) Representative time-course of Ras activation (change in binding fraction) in response to morphine application (black arrow) in control and NF1-DN expressing MSNs. (J) Quantification of Ras response to morphine in control and NF1-DN expressing cultures. Unpaired t test **p=0.007, n=19, 18. (K) Schematic outlining strategy for expression of Ras sensor in D1R or D2R expressing MSNs. (L) Representative time course of Ras activation (change in binding fraction) in response to morphine application (black arrow) in D1R and D2R expressing MSNs. (M) Quantification of Ras response to morphine in D1R and D2R expressing MSNs. Unpaired t test **p=0.007, n=13,15. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S2.

To further test specificity of the observed effects, we used a dominant negative strategy to selectively disrupt Gβγ binding to NF1 (Figure 3H). Introduction of the dominant negative NF1 construct that prevents Gβγ binding to NF1 and disrupts signal transfer from the MOR to NF1 (Supplementary Figure 1C–F) blocked morphine-induced Ras activation (Figure 3I,J). This manipulation, once again, had no effect on Ras activation in response to BDNF application (Supplementary Figure 2E). These results suggest that activation of Ras in MSN neurons in response to morphine specifically requires Gβγ interaction with NF1.

We next addressed the cell-specificity of MOR coupling to Ras. Striatal MSNs form two molecularly distinct populations that project to different output regions and distinctly impact behavioral responses: D1 dopamine receptor expressing neurons of the direct pathway (dMSN) and D2 dopamine receptor expressing (D2R) neurons of the indirect pathway (iMSN) [2]. Consistent with its broad distribution in the striatum, NF1 was significantly co-expressed with both D1R and D2R (Supplementary Figure 2F). To assess MOR coupling to Ras in each of these populations we delivered an inverted Ras-sensor donor construct flanked with inverted loxP sites to cultured striatal neurons from D1-Cre or D2-Cre mice (Figure 3K). Using this strategy, Ras sensors are expressed only in cells containing Cre recombinase, allowing Ras activity to be monitored selectively in striatal neurons expressing either D1R or D2R. Application of morphine to striatal cultures from D1-Cre mice elicited robust FLIM-FRET signal changes indicating Ras activation (Figure 3L,M) from nearly all neurons examined (13 out of 15). In contrast, we detected no Ras activation induced by morphine application in cultures from D2-Cre mice. Importantly, responses to BDNF in both cultures were not significantly different from each other (Supplementary Figure 2G) indicating that the conditional imaging strategy can successfully report Ras activation in both MSN populations, if it occurs. Together, these results demonstrate an essential requirement of NF1 for coupling MORs to Ras activation in striatal dMSN neurons.

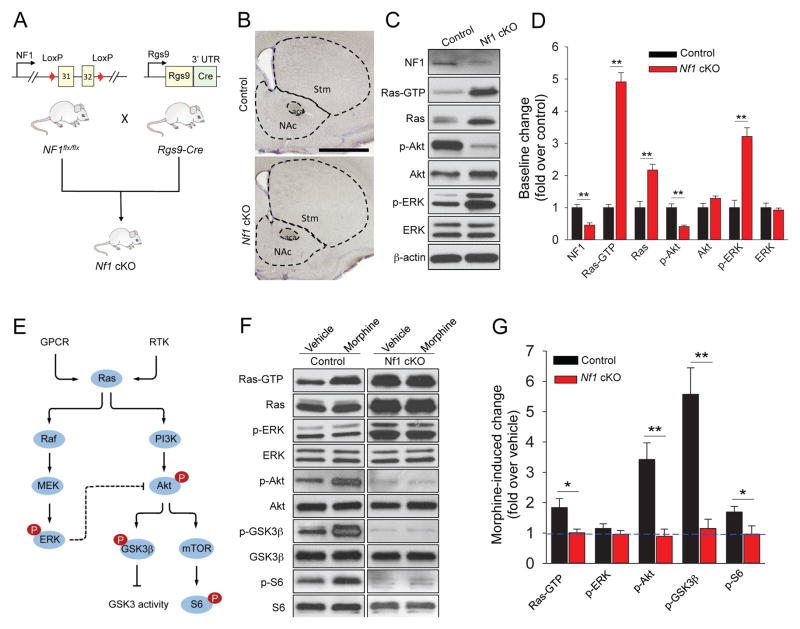

NF1 mediates opioid signaling to Ras-Akt-mTOR in the striatum

We next determined the in vivo relevance of NF1 for opioid mediated signaling in the striatum. Striatal specific inactivation of NF1 (Nf1 cKO) was achieved by crossing conditional Nf1flx/flx mice with the Rgs9-Cre driver line, which expresses Cre recombinase selectively in striatal neurons (Figure 4A). Morphological analysis revealed that Nf1 cKO mice had normal striatal architecture with no evidence of degenerative changes (Figure 4B). Immunoblotting analysis showed a readily detectible reduction in the levels of NF1 protein (Figure 4C,D). As expected from its function as Ras GAP, we detected an elevation in the levels of active Ras in the striatum of Nf1 cKO mice (Figure 4C,D), Consistent with these changes in the baseline activity of Ras, we found a significant elevation in phosphorylation of ERK, a downstream target of Ras (Figure 4C,D; Supplementary Figure S3A). Interestingly, we found the basal activation of Akt, another kinase regulated by Ras signaling to be reduced in Nf1 cKO striatum tissue (Figure 4C,D; Supplementary Figure S3A). While we did not investigate the mechanisms behind this adaptation, we think that it is likely related to known feedback inhibition by activated ERK [26].

Figure 4. Striatal NF1 is essential for morphine-induced Ras and its downstream signaling cascade activation.

(A) Generation of striatal specific Nf1 knockout mice (Nf1 cKO) by crossing conditional NF1flx/flx line with MSNs specific Rgs9-Cre line. (B) Representative images of Nissl-stained coronal brain sections from control and Nf1 cKO mice. Stm, striatum; NAc, nucleus accumbens; aca, anterior part of anterior commissure (Scale bar, 1 mm). We found average volumes of both dorsal striatum (16.4±0.8 mm3 in Nf1 cKO vs 17.2±0.3 mm3 in control littermates, n=4 mice) and nucleus accumbens (1.4±0.1 mm3 in Nf1 cKO vs 1.3±0.1 mm3 in control littermates, n=4 mice) to be unaffected by NF1 deletion. (C) Impact of NF1 elimination on baseline Ras activation and signaling to downstream kinase pathways in striatum. (D) Quantification of Western blot data with activities normalized to samples from control mice. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. **p<0.01, Student’s t-test. (E) Schematic representation of Ras-ERK and Ras-Akt signaling. Ras is activated in response to both GPCRs and receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), which in turn is able to activate both Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways. Activated Akt can further modulate GSK3 and mTOR activity. High level of ERK activity can result in decreased activity of Akt through crosstalk. (F) Morphine-induced activation of Ras and its downstream pathway in striatum studied by Western blotting. Mice were injected with 20 mg/kg morphine (s.c.) or saline and their NAc regions were dissected 60 minutes after for active Ras pull down as well as Western blot analysis. (G) Quantification of Western blot data with activities normalized to vehicle-treated control of the same genotype. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, n=3 mice per each treatment, Student’s t-test. See also Figure S3.

To study the role of NF1 in MOR-mediated signaling we focused on two separate signaling branches downstream from Ras: Raf-ERK and Akt-mTOR/GSK3β (Figure 4E). Administration of morphine (20 mg/kg for 1 hour) resulted in significant elevation of active Ras (Ras-GTP) in the striatum of control mice but not in Nf1 cKO mice (Figure 4F,G). Accordingly, morphine injections increased phosphorylation of Akt, GSK3β and mTOR in control mice but completely failed to do so in the absence of NF1 (Figure 4F,G). In agreement with previous reports [21], we did not detect significant ERK activation in response to morphine in either control or Nf1 cKO mice, suggesting that MOR-mediated activation of Ras in the striatum primarily signals via the Akt-mTOR/GSK3β pathway with NF1 playing a key role in this process. To test whether the lack of kinase pathway by morphine in Nf1 cKO mice could be explained by the signaling occlusion due to elevated basal levels of active Ras, we stereotaxically injected BDNF in the striatum. This treatment resulted in significant Ras activation as well as phosphorylation of AKT, ERK and S6 in both genotypes, indicating that elimination of NF1 does not completely prevent further regulation of Ras signaling pathways (Supplementary Figure S3B).

Ablation of NF1 in the striatum blunts behavioral responses to morphine

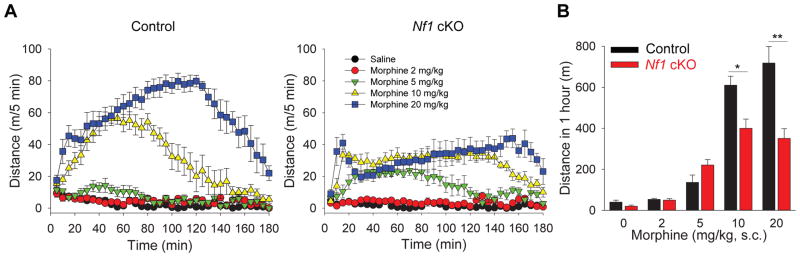

We next examined the effects of striatal NF1 ablation on opioid induced behaviors. Open field test revealed that Nf1 cKO mice had overall normal behavioral reactions including spontaneous locomotor activity, habituation, anxiety and motor coordination (Supplementary Figure 4A–C). Administration of morphine produced significantly lower psychomotor activation in Nf1 cKO mice (Figure 5A,B). Interestingly, the onset, duration and recovery of mice from psychomotor activation produced by morphine action were similar between genotypes yet the effect of morphine in Nf1 cKO mice plateaued, much below the level seen in control mice (Figure 5A,B). We found no effect of NF1 ablation on morphine analgesia or analgesic tolerance (Supplementary Figure 4D) despite demonstrated role of neurons where RGS9-Cre driver is active in these processes [27].

Figure 5. Striatal NF1 regulates psychomotor responses to morphine.

(A) The effect of morphine administration on locomotor activity in control (left) and Nf1 cKO (right) mice in the open field task. Mice received saline or increasing doses of morphine (2, 5, 10, 20 mg/kg, s.c.) and were immediately placed in the activity-recording chamber. (B) Quantification of cumulative distance traveled in open–field chamber during 20 to 80 min following vehicle or morphine treatment. NF1 ablation in striatum results in blunted morphine-induced psychomotor activation. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, Two-Way ANOVA post hoc Tukey’s test (n=8 mice per each group). See also Figure S4.

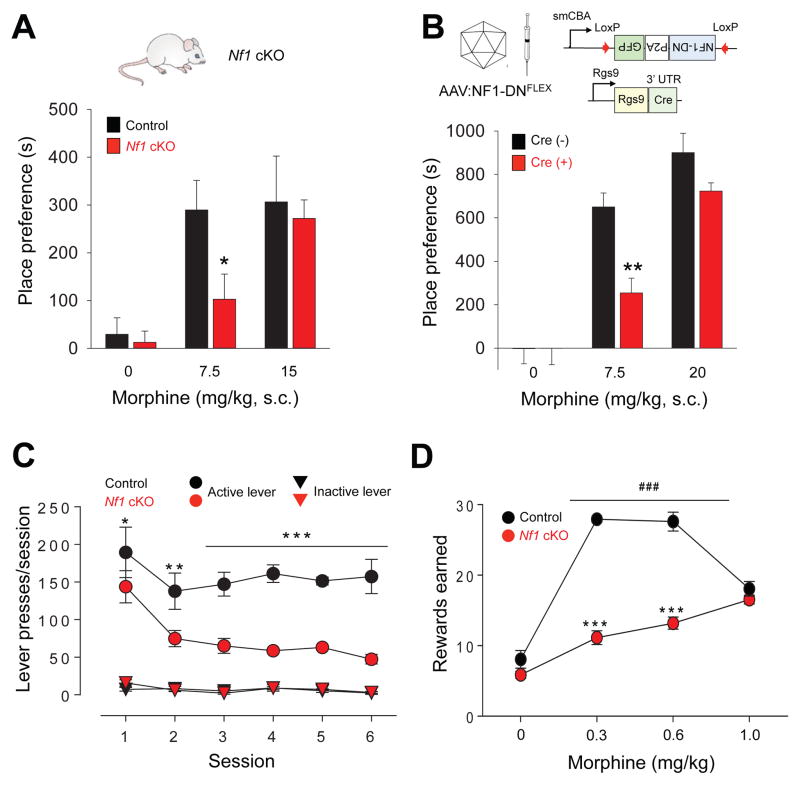

Because striatum plays a central role in mediating the reinforcing effects of opioids we next probed the contribution of striatal NF1 ablation in reward-related behaviors. In the conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm, injection of 7.5 mg/kg morphine caused a significant increase in time spent in the drug-paired side in both Nf1 cKO mice and their control littermates (Figure 6A). However, the effect was significantly less pronounced in mice lacking NF1. This difference between genotypes was eliminated at a higher dose of morphine (20 mg/kg) suggesting that lack of NF1 decreases sensitivity of morphine reward. We then assessed the selective contribution of MOR signaling via NF1 to the observed effect. This was achieved by injecting an AAV virus containing inverted sequence of NF1-DN dominant negative construct to prevent Gβγ binding to NF1 in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) of Rgs9-Cre mice limiting the effects to the striatal MSN neurons (Figure 6B). Again, antagonizing Gβγ-NF1 interaction diminished sensitivity of mice to place-preference inducing effects of morphine, phenocopying the effects of Nf1 ablation.

Figure 6. Disruption of MOR signaling via NF1 in the striatum decreases sensitivity to morphine reward.

(A) Effect of striatal specific deletion of NF1 (Nf1 cKO mice) on mouse performance in conditioned place preference (CPP) task. Mice were administered either saline (0 mg/kg morphine) or various concentrations of morphine as indicated. Place preference scores are calculated as the time difference during post-conditioning between drug-paired side versus saline-paired side. * p < 0.05 in comparison between genotypes Two-Way ANOVA post hoc Tukey’s test (n=6–10 each group). (B) Effect of disrupting Gβγ-NF1 interaction in the Nucleus Accumbens (NAc) on morphine CPP. Upper, Schematics of the conditional dominant negative construct (AAV-NF1-DNFLEX) and its viral delivery into NAc of Rgs9-Cre mice. Lower, Performance of mice in the CPP task. Mice were administered either saline or various concentrations of morphine as indicated. AAV- mediated expression of a dominant negative NF1 construct that prevents Gβγ-NF1 interaction decreases sensitivity of mice to rewarding effects of morphine. The same AAV-NF1-DNFLEX virus was injected into either Rgs9-Cre(+) mice or their control littermates Rgs9-Cre(−). CPP experiments were conducted as in A. ** p < 0.01 in comparison between genotypes Two-Way ANOVA post hoc Tukey’s test (n=5–6 each group). (C) Animal performance in morphine self-administration task. Lever presses per session are plotted. Active (0.3mg/kg/infusion) vs. Inactive levers showed significant (p<0.01 and p<0.0001) difference with both genotypes and within criteria. Genotype vs. Session (n=5 per group) Interaction p= 0.005, Genotype p<0.0001, Session p<0.0001. Data expressed as mean ± SEM *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 genotype comparison per session, two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test. (D) Dose-response dependence of drug taking in the self-administration task. Genotype vs. Dose (n=5 per group) Interaction p<0.0001, Genotype p<0.0001, Dose p<0.0001. Data is expressed by mean ± SEM ***p<0.001 genotype comparison, ###p<0.001 compared to Saline for both genotypes, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni test.

Next, we investigated reinforcing properties of morphine in a morphine self-administration paradigm, which models drug seeking and taking behavior. Initially, mice were trained in a two-lever operant task with food reward (Supplementary Figure 4E). While both genotypes learned the task to the set criteria, it had taken considerably longer for Nf1 cKO mice to establish similar level of lever pressing. Once response to food reinforcement was established, mice were assessed for lever pressing that resulted in morphine infusions (Figure 6C). Both genotypes readily self-administered morphine at a dose of 0.3 mg/kg/infusion; however Nf1 cKO mice exhibited a dramatically decreased number of active lever presses, with no change to inactive lever pressing (Figure 6C). This experiment demonstrates that Nf1 cKO mice have a lower sensitivity to reinforcing effects of morphine. Analysis of the dose-response relationship revealed that Nf1 cKO mice earned a lower number of morphine infusions compared to control littermates at the doses of 0.3 and 0.6 mg/kg/infusion (Figure 6D; Supplemental Figure 4F). Interestingly, while control mice responded with decreased morphine intake at a higher dose (1 mg/kg/session) and showed typical inverted U–shaped dependence, Nf1 cKO mice continued to press even more, earning a greater number of rewards (Figure 6D). Both genotypes showed similar extinction profile upon substitution of morphine with saline, further supporting the conclusion that differences in lever pressing behavior were related to differences in reinforcing effects of morphine rather than in habitual behaviors. Together, these observations indicate that NF1 is involved in setting the behavioral sensitivity of mice to the rewarding effects of morphine.

DISCUSSION

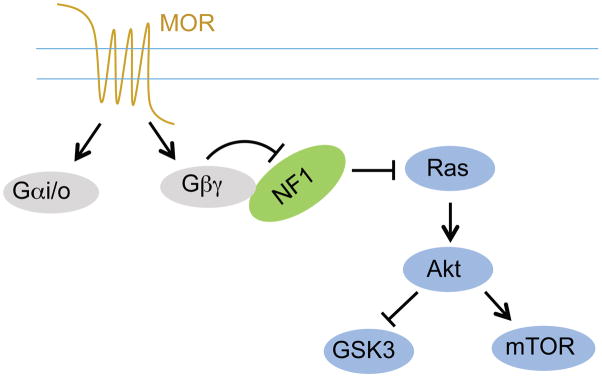

One of the main results of this study is the demonstration of a novel signaling mechanism for transmitting GPCRs activation to positive regulation of kinase signaling networks (Figure 7). On the basis of our findings, we propose that NF1 is a direct G protein effector. Inhibition of its Ras GAP activity by Gβγ subunits released upon activation of opioid receptors in striatal neurons resulted in activation of small GTPase Ras. Elimination of NF1 led to elevation of baseline Ras activity and abolished the ability of opioid receptors to regulate Ras activation. This deficit in signal propagation selectively affected responses mediated by the heterotrimeric G proteins and did not influence signaling via receptor tyrosine kinases that activate Ras directly.

Figure 7. Proposed model for the role of NF1 in mediating MOR signaling to Ras.

NF1 is a novel Gβγ effector downstream from MORs activation and is essential for MORs-induced Ras pathway activation in MSNs.

Activation of Ras by GPCRs has become an accepted paradigm in cellular signaling. A large number of mechanisms have been proposed to explain how GPCRs signal to Ras (see[28, 29] for review). Majority of the demonstrated mechanisms involve multiple steps and have been described for non-neuronal cell lines. Perhaps the most direct pathway occurs in epithelial cells and involves positive regulation of the Ras exchange factor Ras-GRF1 by Gβγ in a phosphorylation dependent manner [9], although there is evidence for Gβγ binding to several GEFs for small GTPases [22, 30] as well as some GAPs, e.g. p120Ras-GAP [31]. To the best of our knowledge, however, this work for the first time identified a mechanism for GPCR-mediated activation of Ras in native neuronal cells, making NF1 the first reported GAP for the small GTPases regulated by GPCR signaling. Remarkably, we found that this is the dominant signaling transfer mechanism in the striatal neurons, as the elimination of NF1 completely prevented coupling of opioid receptors to Ras despite multiple potential pathways described in non-neuronal cell types.

The role of NF1 in neuronal function is a subject of intense investigation, largely because mutations in NF1 cause neurofibromatosis, a disease with prominent neuropsychiatric manifestations that include learning and memory issues, social difficulties and delays in the acquisition of motor and idiopathic pain [32]. While there has been great progress linking cognitive deficits associated with NF1 deficiency to hippocampal function [33], the broad range of the neuropsychiatric features suggest that NF1 is involved in controlling neuronal functions in other brain regions as well. Among these, the involvement of striatal circuits has been suggested [34, 35]. The results of our study reveal that NF1 plays an essential role in the processing neurotransmitter signals in the striatal medium spiny neurons. Acting primarily in D1 receptor- expressing direct pathway neurons, NF1 plays an essential role in linking MOR to Ras activation. We found that this NF1 function was necessary for achieving full efficacy of behavioral responses to morphine establishing it as a key player in controlling opioid effects in the striatum. Interestingly, we find that NF1 plays a critical role in producing rewarding and motivational effects of morphine administration with no impact on morphine-mediated analgesia.

We think that effect of NF1 elimination on behavior and signaling in striatal neurons is unlikely to be limited to blockade of MOR signaling to Ras. Loss of NF1 also results in significant elevation of basal activation of Ras and downstream pERK pathway with concurrent inhibition of basal AKT-mTOR signaling. This effect is expected from the activity of NF1 as a Ras GAP and consistent with similar observations in other cells [36, 37]. Although these changes in baselines were substantial, they did not reach the saturation and stimulation of receptor tyrosine kinase receptors by BDNF led to further augmentation of Ras activation indicating that even if signaling occlusion occurs, is not complete. Nevertheless, these alterations in baselines of several signaling molecules may contribute to the changes in responses to morphine brought about by NF1 deletion. Furthermore, other second messenger cascades and receptor systems involved in shaping complex behavioral response to a drug may be affected and thus be also contributing to the observed phenotypes. Regardless of the exact contributions of baseline vs. receptor mediated signaling through Ras pathways, our findings clearly establish the key role of NF1 in the process.

Given that the endogenous opioid system plays a role in the actions of many abused drugs including alcohol [38], we think it is likely that the MOR-NF1-Ras pathway in the striatum may be involved in setting the incentive salience value of incoming signals and thus contributing to controlling addictive properties of drugs in general. In agreement with this idea, mutations in NF1 have recently been associated with predisposition to alcohol addiction and NF1 haploinsufficiency protected mice from developing dependence [39]. Furthermore, we found that NF1 ablation also diminished acquisition of lever pressing behavior when food was used as a reinforcer. Although this may be related to deficits in the instrumental learning, which striatum is involved in, we think that it is equally plausible that this may also suggest a role of NF1 in controlling endogenous opioid system, as it has been shown to play prominent role in regulating food reward [40]. Together, our observations introduce NF1 as a key regulator of opioid signaling and reward processing in the striatum.

Activation of Ras is one of the central hubs in cellular signaling which can engage a variety of the signaling pathways downstream. From this perspective it is interesting that, in striatal neurons, activation of Ras-regulated kinase pathways by MOR is functionally biased. In agreement with previous reports [21, 41, 42], we found that morphine did not increase ERK1/2 phosphorylation despite robust activation of Ras. Instead, regulation of the Akt signaling branch by morphine was clearly evident. At the same time, elimination of NF1 affected basal levels of both Akt-mTOR and ERK1/2 activation, suggesting that this bias likely originates at the level of the receptor. Indeed, MOR has been shown to be capable of activating ERK1/2 in striatal neurons when stimulated by a different opioid agonist fentanyl in a manner dependent on GRK3/β-arrestin [41]. This example serves to reinforce the ligand dependent nature of opioid receptor signaling that is becoming an increasingly accepted model of GPCR signaling [43, 44]. Nevertheless, from the perspective of G protein mediated transmission downstream from MOR, Ras signaling to Akt-mTOR/GSK3β seems to be the dominant pathway regulated by NF1. Another interesting observation is that, in striatal neurons, the homeostatic set point for the regulation of basal Akt-mTOR/GSK3β activity appears to differ from that seen in other cells. While the elimination of NF1 in astrocytes results in Akt-mTOR hyperactivation [45], we observed hypoactivity of Akt-mTOR signaling in striatal tissue lacking NF1. We think that this down-regulation of basal Akt signaling results from a negative feedback imposed by excessive ERK1/2 activity, which was reported to occur in human breast cancer cells [26, 46]. The exact molecular mechanisms of this ERK1/2-Akt signaling cross-talk are not well understood, and determining the role of NF1 in this process along with its implication for neuronal physiology appears to be an interesting direction for future studies.

The loss of the receptor mediated activation of Ras in the striatal neurons that we report in this study calls for revisiting the current paradigm that views upregulation of Ras signaling as a primary cause of neurofibromatosis [47, 48]. This rationale provides a theoretical basis for Ras inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for neurofibromatosis treatment. However, clinical trials using statins that reduce Ras activation have had mixed success in ameliorating neuropsychiatric symptoms of the disease [49, 50]. While our results confirm the well-documented increase in basal levels of active Ras associated with NF1 dysfunction, they additionally reveal that the signal-regulated Ras activation (e.g. through MOR activation) is abolished. Thus, insufficiency of signaling through Ras may contribute to some of the neuropsychiatric manifestations seen in type 1 neurofibromatosis. From this perspective, NF1-mediated opioid signaling to Ras in the striatum may prove helpful for understanding related aspects of the disease, such as goal directed learning difficulties as well as for exploring opioid receptors as possible therapeutic targets for neurofibromatosis. While our research primarily focused on examining the role of NF1 in the regulation of opioid receptor signaling specifically in the striatal neurons, we think that these observations could be broadly applicable to other cells and GPCRs where NF1 plays a dominant role in controlling basal Ras activation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer assay

A new version of NanoBRET was performed to visualize the interaction between the nanoluc-tagged energy donor and the Venus-tagged energy acceptor. NanoBRET assays were applied to examine NF1 membrane recruitment, the specific interaction between Sec14/PH and Gβγ, and the real time interaction between Sec4/PH and Gβγ upon GPCR activation/inactivation.

Ras GTP hydrolysis assay

Ras GTPase activity was examined in both single and multiple turnover Ras GTP hydrolysis assays using purified recombinant proteins. GTP hydrolysis was examined by measuring the generation of inorganic phosphate 32Pi released from hydrolyzed [γ-32P]GTP by activated charcoal assay.

Ras activity measured by two-photon fluorescence lifetime imaging assay

Cultured striatal neurons were transfected with the FLIM-FRET Ras sensors mEGFP-HRas and mRFP-RBD-mRFP and imaged under a two-photon microscope. Fluorescence lifetime images were acquired using time-correlated single photon counting and Ras activation was quantified as fraction of mEGFP-HRas bound to mRFP-RBD-mRFP through fitting the fluorescence decay curve.

Animals

Homozygous Nf1flx/flx mice were bred against heterozygous Rgs9-Cre mice to generate striatal specific NF1 conditional knockout (Nf1 cKO) mice. Mice of either sex were used.

Statistics

All data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Two sample comparisons were made using the Student’s t test. All comparisons relating test to control data from littermate animals were analyzed statistically using Two Way ANOVA.

Additional details are in Supplemental Experimental Procedures

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Ms. Natalia Martemyanova for producing and maintaining mice examined in this study and Maxwell Kassel for technical help with some of the experiments. This work was supported by NIH grants: DA036082 (KAM), MH080047 (RY), MH101954 (LAC), NS82244 (YL), NS073930 (BX), EY024280 (SEB) and Department of Defense CDMRP grant W81XWH-14-1-0074 (KAM).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.X. performed all biochemical experiments described in the paper, including protein-protein interaction assays, BRET studies, in vitro GAP assays, he also performed behavioral studies, analyzed data and wrote the paper; S.L.B and S.E.B have designed and generated recombinant AAV vectors. L.A.C. performed FLIM-FRET experiments in striatal neurons and analyzed the data; C.O. performed in situ hybridization experiments; B.S.M. conducted BRET, co-IP studies and experiments involving D1-Cre and D2-Cre cultured neurons; L.P.S. designed and executed hot-plate behavioral experiments; C.C.H. and B.X. performed morphological analysis of striatum and analyzed the data; Y.L. provided RGS9-Cre mouse strain; M.T.D. and R.G.S. designed and executed self administration experiments; M.D. performed viral injections and some CPP experiments; R.Y. designed FLIM-FRET experiments and analyzed the data; K.A.M. designed the study, analyzed data and wrote the paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Graybiel AM. The basal ganglia. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R509–511. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00593-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kreitzer AC, Malenka RC. Striatal plasticity and basal ganglia circuit function. Neuron. 2008;60:543–554. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie K, Martemyanov KA. Control of striatal signaling by g protein regulators. Front Neuroanat. 2011;5:49. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2011.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierce KL, Premont RT, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:639–650. doi: 10.1038/nrm908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fasano S, Brambilla R. Ras-ERK Signaling in Behavior: Old Questions and New Perspectives. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience. 2011;5:79. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2011.00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas GM, Huganir RL. MAPK cascade signalling and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:173–183. doi: 10.1038/nrn1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crespo P, Xu N, Simonds WF, Gutkind JS. Ras-dependent activation of MAP kinase pathway mediated by G-protein beta gamma subunits. Nature. 1994;369:418–420. doi: 10.1038/369418a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koch WJ, Hawes BE, Allen LF, Lefkowitz RJ. Direct evidence that Gi-coupled receptor stimulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase is mediated by G beta gamma activation of p21ras. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:12706–12710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mattingly RR, Macara IG. Phosphorylation-dependent activation of the Ras-GRF/CDC25Mm exchange factor by muscarinic receptors and G-protein beta gamma subunits. Nature. 1996;382:268–272. doi: 10.1038/382268a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bos JL, Rehmann H, Wittinghofer A. GEFs and GAPs: critical elements in the control of small G proteins. Cell. 2007;129:865–877. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Merrer J, Becker JA, Befort K, Kieffer BL. Reward processing by the opioid system in the brain. Physiological reviews. 2009;89:1379–1412. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00005.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nestler EJ. Molecular basis of long-term plasticity underlying addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:119–128. doi: 10.1038/35053570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Law PY, Wong YH, Loh HH. Molecular mechanisms and regulation of opioid receptor signaling. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;40:389–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mansour A, Fox CA, Burke S, Meng F, Thompson RC, Akil H, Watson SJ. Mu, delta, and kappa opioid receptor mRNA expression in the rat CNS: an in situ hybridization study. J Comp Neurol. 1994;350:412–438. doi: 10.1002/cne.903500307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oude Ophuis RJ, Boender AJ, van Rozen AJ, Adan RA. Cannabinoid, melanocortin and opioid receptor expression on DRD1 and DRD2 subpopulations in rat striatum. Front Neuroanat. 2014;8:14. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui Y, Ostlund SB, James AS, Park CS, Ge W, Roberts KW, Mittal N, Murphy NP, Cepeda C, Kieffer BL, et al. Targeted expression of mu-opioid receptors in a subset of striatal direct-pathway neurons restores opiate reward. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:254–261. doi: 10.1038/nn.3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robinson TE, Kolb B. Morphine alters the structure of neurons in the nucleus accumbens and neocortex of rats. Synapse. 1999;33:160–162. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199908)33:2<160::AID-SYN6>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Russo SJ, Dietz DM, Dumitriu D, Morrison JH, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ. The addicted synapse: mechanisms of synaptic and structural plasticity in nucleus accumbens. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ye X, Carew TJ. Small G protein signaling in neuronal plasticity and memory formation: the specific role of ras family proteins. Neuron. 2010;68:340–361. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazei-Robison MS, Koo JW, Friedman AK, Lansink CS, Robison AJ, Vinish M, Krishnan V, Kim S, Siuta MA, Galli A, et al. Role for mTOR signaling and neuronal activity in morphine-induced adaptations in ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons. Neuron. 2011;72:977–990. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muller DL, Unterwald EM. In vivo regulation of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) and protein kinase B (Akt) phosphorylation by acute and chronic morphine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:774–782. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.066548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inglese J, Koch WJ, Touhara K, Lefkowitz RJ. G beta gamma interactions with PH domains and Ras-MAPK signaling pathways. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:151–156. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)88992-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishida K, Kaziro Y, Satoh T. Association of the proto-oncogene product dbl with G protein betagamma subunits. FEBS Lett. 1999;459:186–190. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01244-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Angelo I, Welti S, Bonneau F, Scheffzek K. A novel bipartite phospholipid-binding module in the neurofibromatosis type 1 protein. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:174–179. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu H, Wang X, Partilla JS, Bishop-Mathis K, Benaderet TS, Dersch CM, Simpson DS, Prisinzano TE, Rothman RB. Differential effects of opioid agonists on G protein expression in CHO cells expressing cloned human opioid receptors. Brain research bulletin. 2008;77:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klos KS, Wyszomierski SL, Sun M, Tan M, Zhou X, Li P, Yang W, Yin G, Hittelman WN, Yu D. ErbB2 increases vascular endothelial growth factor protein synthesis via activation of mammalian target of rapamycin/p70S6K leading to increased angiogenesis and spontaneous metastasis of human breast cancer cells. Cancer research. 2006;66:2028–2037. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zachariou V, Georgescu D, Sanchez N, Rahman Z, DiLeone R, Berton O, Neve RL, Sim-Selley LJ, Selley DE, Gold SJ, et al. Essential role for RGS9 in opiate action. 2003;100:13656–13661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2232594100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gutkind JS. Regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling networks by G protein-coupled receptors. Sci STKE. 2000;2000:re1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2000.40.re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wetzker R, Bohmer FD. Transactivation joins multiple tracks to the ERK/MAPK cascade. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:651–657. doi: 10.1038/nrm1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niu J, Profirovic J, Pan H, Vaiskunaite R, Voyno-Yasenetskaya T. G Protein betagamma subunits stimulate p114RhoGEF, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for RhoA and Rac1: regulation of cell shape and reactive oxygen species production. Circ Res. 2003;93:848–856. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000097607.14733.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu N, Coso O, Mahadevan D, De Blasi A, Goldsmith PK, Simonds WF, Gutkind JS. The PH domain of Ras-GAP is sufficient for in vitro binding to beta gamma subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1996;16:51–59. doi: 10.1007/BF02578386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Creange A, Zeller J, Rostaing-Rigattieri S, Brugieres P, Degos JD, Revuz J, Wolkenstein P. Neurological complications of neurofibromatosis type 1 in adulthood. Brain: a journal of neurology. 1999;122(Pt 3):473–481. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Costa RM, Federov NB, Kogan JH, Murphy GG, Stern J, Ohno M, Kucherlapati R, Jacks T, Silva AJ. Mechanism for the learning deficits in a mouse model of neurofibromatosis type 1. Nature. 2002;415:526–530. doi: 10.1038/nature711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shilyansky C, Karlsgodt KH, Cummings DM, Sidiropoulou K, Hardt M, James AS, Ehninger D, Bearden CE, Poirazi P, Jentsch JD, et al. Neurofibromin regulates corticostriatal inhibitory networks during working memory performance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13141–13146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004829107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown JA, Xu J, Diggs-Andrews KA, Wozniak DF, Mach RH, Gutmann DH. PET imaging for attention deficit preclinical drug testing in neurofibromatosis-1 mice. Exp Neurol. 2011;232:333–338. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Basu TN, Gutmann DH, Fletcher JA, Glover TW, Collins FS, Downward J. Aberrant regulation of ras proteins in malignant tumour cells from type 1 neurofibromatosis patients. Nature. 1992;356:713–715. doi: 10.1038/356713a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bollag G, Clapp DW, Shih S, Adler F, Zhang YY, Thompson P, Lange BJ, Freedman MH, McCormick F, Jacks T, et al. Loss of NF1 results in activation of the Ras signaling pathway and leads to aberrant growth in haematopoietic cells. Nat Genet. 1996;12:144–148. doi: 10.1038/ng0296-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Froehlich JC, Li TK. Opioid involvement in alcohol drinking. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;739:156–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb19817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Repunte-Canonigo V, Herman MA, Kawamura T, Kranzler HR, Sherva R, Gelernter J, Farrer LA, Roberto M, Sanna PP. Nf1 regulates alcohol dependence-associated excessive drinking and gamma-aminobutyric acid release in the central amygdala in mice and is associated with alcohol dependence in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77:870–879. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nogueiras R, Romero-Pico A, Vazquez MJ, Novelle MG, Lopez M, Dieguez C. The opioid system and food intake: homeostatic and hedonic mechanisms. Obes Facts. 2012;5:196–207. doi: 10.1159/000338163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Macey TA, Lowe JD, Chavkin C. Mu opioid receptor activation of ERK1/2 is GRK3 and arrestin dependent in striatal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34515–34524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604278200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Urs NM, Daigle TL, Caron MG. A dopamine D1 receptor-dependent beta-arrestin signaling complex potentially regulates morphine-induced psychomotor activation but not reward in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:551–558. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kelly E. Efficacy and ligand bias at the mu-opioid receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;169:1430–1446. doi: 10.1111/bph.12222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Violin JD, Crombie AL, Soergel DG, Lark MW. Biased ligands at G-protein-coupled receptors: promise and progress. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2014;35:308–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banerjee S, Crouse NR, Emnett RJ, Gianino SM, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis-1 regulates mTOR-mediated astrocyte growth and glioma formation in a TSC/Rheb-independent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:15996–16001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019012108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turke AB, Song Y, Costa C, Cook R, Arteaga CL, Asara JM, Engelman JA. MEK inhibition leads to PI3K/AKT activation by relieving a negative feedback on ERBB receptors. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3228–3237. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ferner RE, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1): diagnosis and management. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;115:939–955. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52902-2.00053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shilyansky C, Lee YS, Silva AJ. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of learning disabilities: a focus on NF1. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2010;33:221–243. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Acosta MT, Kardel PG, Walsh KS, Rosenbaum KN, Gioia GA, Packer RJ. Lovastatin as treatment for neurocognitive deficits in neurofibromatosis type 1: phase I study. Pediatr Neurol. 2011;45:241–245. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van der Vaart T, Plasschaert E, Rietman AB, Renard M, Oostenbrink R, Vogels A, de Wit MC, Descheemaeker MJ, Vergouwe Y, Catsman-Berrevoets CE, et al. Simvastatin for cognitive deficits and behavioural problems in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1-SIMCODA): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:1076–1083. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.