Abstract

Objectives

Preoperative testing for carotid endarterectomy (CEA) often includes blood typing and antibody screen (T&S). In our institutional experience, however, transfusion for CEA is rare. We assessed transfusion rate and risk factors in a national clinical database to identify a cohort of patients in whom T&S can safely be avoided with the potential for substantial cost savings.

Methods

Using the NSQIP database, transfusion events and timing were established for all elective CEAs in 2012–13. Comorbidities and other characteristics were compared for patients receiving intra- or postoperative transfusion and those that did not. After random assignment of the total data to either a training or validation set, a prediction model for transfusion risk was created and subsequently validated.

Results

Of 16,043 patients undergoing CEA in 2012–13, 276 received at least one transfusion prior to discharge (1.7%). 42% of transfusions occurred on the day of surgery. Preoperative hematocrit < 30% (Odds ration OR: 57.4; 95% confidence interval CI: 29.6–111.1), history of congestive heart failure (OR: 2.8; 95%CI: 1.1 – 7.1), dependent functional status (OR: 2.7; 95%CI: 1.5–5.1), coagulopathy (OR: 2.5; 95%CI: 1.7–3.6), creatinine ≥ 1.2 mg/dl (OR: 2.3; 95%CI: 1.6–3.3) preoperative dyspnea (OR: 2.0; 95%CI: 1.4–3.1) and female gender (OR: 1.6; 95%CI: 1.1–2.3) predicted transfusion. A risk prediction model based on these data produced a C-statistic of 0.85; application of this model to the validation set demonstrated a C-statistic of 0.81. 93% of patients in the validation set received a score of 6 or less corresponding to an individual predicted transfusion risk of 5% or less. Omitting a T&S in these patients would generate a substantial annual cost saving for NSQIP hospitals.

Conclusions

While T&S is commonly performed for patients undergoing CEA, transfusion following CEA is rare and well predicted by a transfusion risk score. Avoidance of T&S in this low-risk population provides a substantial cost-saving opportunity without compromise of patient care.

INTRODUCTION

Most arterial procedures in vascular surgery fall into the category of ‘high risk’ surgery. Independent of patient-associated factors, the modified Johns Hopkins surgical criteria assign risk based on invasiveness, potential for blood loss and need for perioperative invasive monitoring in an intensive care unit (ICU).1 It is customary for these patients to undergo thorough preoperative testing such as determination of blood type and red blood cell antibody screen (type and screen, T&S). Often a crossmatch is also performed in anticipation of acute blood loss and subsequent reduced oxygen delivery to tissues. Patients with preexisting cardiovascular disease are at increased risk from adverse effects of acute anemia.2 Carotid endarterectomy (CEA), however, does not belong to this ‘high-risk’ group. It lacks the required potential for blood loss > 1500 mL as well as need of invasive ICU monitoring. Despite the apparent moderate cardiac risk profile demonstrated in multiple randomized trials involving CEA3–5, comprehensive preoperative laboratory testing including T&S and even crossmatching are usually undertaken. This approach is frequently demanded by institutional committees despite the absence of strong recommendations in favor of this practice by the relevant specialty societies.6,7 Our institution follows the same approach, as do many others (e.g. Massachusetts General Hospital, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both Boston, MA; Maine Medical Center, Portland, ME; personal communication). This practice is possibly overly cautious and certainly expensive. Based on institutional and thus rather limited data on 126 patients, Couture et al. suggested that preoperative T&S can be avoided in CEA without undue risk to patients.8 In an effort to identify those patients at greatest risk for transfusion, we utilized a prospectively collected, national clinical database to identify the incidence of intra- or postoperative transfusion and compare those patients receiving transfusion to those who did not. We then aimed to develop a point-based risk prediction model to identify a patient population, in which T&S can safely be avoided, thus creating an opportunity for substantial cost savings.

METHODS

Data Source/Patients

This retrospective case-control study was performed using the NSQIP Participant User File (PUF), a national, prospectively collected clinical database including 435 institutions as of 2013. Additional data from the Carotid Endarterectomy Targeted PUF was utilized, though this received cases from a minority of centers (N=83). All patients undergoing elective carotid endarterectomy without concurrent additional procedures were identified using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 35301. Data collection details, definitions and protocols are outlined in the NSQIP User Guide.9 The NSQIP data are audited annually with year on year improvement in data reliability and accuracy.10 Specifically, the 2012–2013 NSQIP was chosen as the data source related to a change in data capture from prior iterations that allowed for identification and quantification of blood transfusion both in and out of the operating room. Baseline patient demographics, comorbidities, operative details and postoperative course were extracted from the database. This study contained de-identified data without any protected health information and as such was exempt from institutional review board approval or need for obtaining informed consent.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the need for intraoperative or postoperative red blood cell transfusion as captured by the NSQIP. Number of days from operation to transfusion were also recorded with transfusions occurring after discharge excluded from consideration. Neither indication for transfusion nor level of hemoglobin or hematocrit at the time of transfusion are available in the database. The number of red blood cell units transfused is not available in the NSQIP database. Secondary outcome measures included the cost associated with performance of ABO-Rh blood typing and screening for serum antibodies.

Select NSQIP Definitions

Variables defined here are those collected by the NSQIP whose definitions are not apparent based on their description. For a full list of available variables and their definitions please refer to the aforementioned general and targeted NSQIP manuals. In the NSQIP context, bleeding disorder is defined as “any condition that places the patient at risk for excessive bleeding requiring hospitalization due to a deficiency of blood clotting elements (e.g., vitamin K deficiency, hemophilias, thrombocytopenia, chronic anticoagulation therapy that has not been discontinued prior to surgery)”.9 Importantly, this does not include patients on chronic aspirin therapy. Preoperative open wound refers to patients with a documented preoperative “breach in the integrity of the skin or separation of skin edges including open surgical wounds, with or without cellulitis or purulent exudate”.9 Preoperative dyspnea is characterized as “difficult, painful or labored breathing” and is intended by the NSQIP to “capture the usual or typical level of dyspnea (patient’s baseline), within the 30-days prior to surgery” as a reflection of a chronic disease state. Physiologic high risk is defined as patients with one or more of the following conditions: New York Heart Association congestive heart failure class III/IV, left ventricular ejection fraction less than 30%, unstable angina and/or myocardial infarction within 30 days preoperatively. Anatomic high risk is defined as patients with one or more of these characteristics: recurrent stenosis following prior CEA or carotid artery stenting, prior radical neck dissection, contralateral laryngeal nerve injury/palsy, anatomic lesion located at cervical vertebrae 2 or higher.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0.0.1 for Macintosh (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). A risk score for intraoperative or postoperative transfusion on the index admission was developed using available preoperative patient comorbidities, use of medications and other characteristics (partial list available in table I, see NSQIP manual for complete list). Half of the cohort were randomly assigned to the model training set while half were assigned to the validation set.11 Multivariable binary logistic regression was performed using the training set to determine independent predictors of red blood cell transfusion. Variables were entered into the model if found to have a p value less than 0.10 on bivariate analysis of the training set for comparison of those receiving blood transfusion and those that did not. Bivariate analysis was carried out with chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and two-tailed independent samples t-test for continuous variables. Cases with missing data for a particular parameter were eliminated from consideration for the purposes of bivariate analysis. For the purposes of regression modeling, cases with missing data had the missing parameter set to the reference group for that parameter. This maximizes sample size while producing estimates that are biased toward the null hypothesis.12,13 Backward stepwise elimination was used to determine final independent predictors with variables eliminated for p-value greater than 0.05. Model discrimination was assessed using the c-statistic with a c-statistic of 1.0 denoting perfect discrimination and a c-statistic of 0.5 representing discrimination equivalent to random chance. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was used to assess model calibration. A Brier score was calculated to assess model accuracy with a score of 0 representing perfect accuracy and a score of 1 representing poor model accuracy.

Table 1.

Preoperative patient characteristics and comorbidities. Only 1.7% of patients received at least one unit of RBC transfusion. Patients receiving a transfusion differed significantly from patients who did not in many examined aspects. Most notably, transfused patients showed significantly higher rates of preoperative dyspnea, bleeding disorder, anemia and elevated creatinine levels. They also had higher rates of functional dependency and ASA classification. Use of any antiplatelet agent was not associated with increased bleeding risk.

| All | Missing Data | No Pre-Discharge Transfusion | Pre-Discharge Transfusion | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 16043 (% of present data) | N (% of total) | N = 15767; 98.2% | N = 276; 1.7% | ||

| Age [years; mean ± SD] | 71.2 ± 9.3 | 0 (0) | 71.2 ± 9.3 | 73.4 ± 9.1 | <.001 |

| Female | 6425 (40) | 0 (0) | 6274 (40) | 151 (55) | <.001 |

| Race | 793 (5) | <.001 | |||

| – White | 14217 (89) | 13996 (89) | 221 (80) | ||

| – Black | 681 (4) | 657 (4) | 24 (9) | ||

| – Asian | 277 (2) | 261 (2) | 16 (6) | ||

| – Other | 75 (1) | 73 (1) | 2 (1) | ||

| Asymptomatic Neurologic Symptom Status* | 4064 (66) | 9898 (62) | 4017 (66) | 47 (60) | 0.231 |

| Physiologic High Risk* | 254 (4) | 9848 (61) | 246 (4) | 8 (10) | 0.015 |

| Anatomic High Risk* | 698 (11) | 9842 (61) | 684 (11) | 14 (18) | 0.07 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 143 (1) | 0 (0) | 133 (1) | 10 (4) | <.001 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 4839 (30) | 0 (0) | 4739 (30) | 100 (36) | 0.028 |

| Smoker | 4535 (28) | 0 (0) | 4457 (28) | 78 (28) | 0.996 |

| Dependent Functional Status | 417 (3) | 66 (0) | 386 (3) | 31 (11) | <.001 |

| Dyspnea | 2420 (15) | 0 (0) | 2344 (15) | 76 (28) | <.001 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 1808 (11) | 0 (0) | 1756 (11) | 52 (19) | <.001 |

| Hemodialysis Dependence | 153 (1) | 0 (0) | 141 (1) | 12 (4) | <.001 |

| Preoperative Open Wound | 149 (1) | 0 (0) | 137 (1) | 12 (4) | <.001 |

| Chronic Steroid Use | 481 (3) | 0 (0) | 466 (3) | 15 (5) | 0.03 |

| Bleeding Disorder | 3275 (20) | 0 (0) | 3169 (20) | 106 (38) | <.001 |

| Preoperative Transfusion > 4 units | 28 (0) | 0 (0) | 23 (0) | 5 (2) | <.001 |

| ASA Class | 0 (0) | <.001 | |||

| – I | 20 (0) | 20 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| – II | 1019 (6) | 1011 (6) | 8 (3) | ||

| – III | 12575 (78) | 12405 (79) | 170 (62) | ||

| – IV | 2418 (15) | 2320 (15) | 98 (36) | ||

| – V | 2 (0) | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| – None | 9 (0) | 9 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Preoperative Antiplatelet Agent* | 5649 (35) | 9797 (61) | 5577 (90) | 72 (90) | 0.848 |

| Preoperative Statin* | 5014 (80) | 9792 (61) | 4953 (80) | 61 (80) | 0.479 |

| Preoperative Beta Blocker* | 3474 (56) | 9819 (61) | 3425 (56) | 49 (62) | 0.305 |

| BMI > 30 kg/m2 | 5374 (34) | 71 (0) | 5317 (34) | 57 (21) | <.001 |

| Hematocrit [mean ±SD] | 39.7 ± 4.7 | 595 (4) | 39.8 ± 4.6 | 33.0 ± 5.2 | <.001 |

| Hematocrit < 30 | 399 (3) | 595 (4) | 309 (2) | 90 (33) | <.001 |

| Serum Creatinine > 1.2 g/dL | 3930 (25) | 592 (4) | 3806 (25) | 124 (46) | <.001 |

- denotes variable included only for patients from the vascular targeted NSQIP module

The beta coefficients from the predictive model in the training set were used to assign points for the transfusion risk score.12,14 Point assignment was carried out by application of an algorithm based on the beta coefficients for each risk factor as described by the Framingham Heart Study investigators.14 The points associated with each risk factor in the model were then added to create an aggregate risk score. The predictive ability of the model generated by the scoring system was assessed via c-statistic, Hosmer-Lemeshow and Brier score as described above. The score based model derived from the training set was then applied to the validation set to assess the performance of the model on novel cases in the manner described above.

Excluded Variables/Subset Analysis

Due to missing data for a large proportion of patients (87% or greater missing), the following variables were excluded from model consideration: myocardial infarction within six months prior to surgery, prior cardiac surgery, prior percutaneous cardiac intervention, recent angina, history of peripheral revascularization or amputation, history of transient ischemic attack, history of cerebrovascular accident with/without neurologic deficit, paraplegia quadriplegia and highest level of resident surgeon.

Variables available only for those cases in the vascular targeted NSQIP module were also eliminated from model consideration as only approximately 39% (N = 6287/16043) of the cohort had available data for these parameters. Anatomic/physiologic high risk, preoperative beta blockade, preoperative statin and preoperative anti-platelet were thus omitted on the basis of missing data (61% missing). However, all vascular targeted cases were evaluated as a subset to evaluate independent predictors of transfusion which would include these variables which were missing for the general cohort. The multivariable binary logistic regression model was created in the same manner as described above.

RESULTS

We identified 16,043 patients undergoing primary elective CEA without a concurrent additional procedure in the 2012–2013 NSQIP database; of these 6,287 (39%) had vascular targeted NSQIP data available. The vast majority of patients did not receive a RBC transfusion; 1.7% of patients (N = 276), however, were transfused at least one unit of RBC before discharge. Preoperative characteristics and laboratory values are presented in Table I. Parameters that are only available from the vascular targeted NSQIP data set are marked (e.g. neurologic symptom status, use of anti-platelet agents, etc.). A number of differences existed between those that received transfusion and those that did not. Patients receiving transfusion were more likely to have preoperative dyspnea (28% vs. 15% in control group, P < 0.001), bleeding disorder (38% vs. 20%, P < 0.001), hematocrit level less than 30% (33% vs. 2%, P < 0.001) and serum creatinine greater than 1.2 mg/dl (46% vs. 25%, P < 0.001) among other differences. Their overall more morbid preoperative state is further supported by higher rates of dependent functional status (11% vs. 3%, P < 0.001) as well as higher ASA classification (3.33 vs. 3.08, P < 0.001). Interestingly, they had a lower body mass index (BMI, 26.7 kg/m2 vs. 28.5 kg/m2, P < 0.001). The operating surgeon was designated as a vascular surgeon in 92% of cases (N=14736) with no difference in surgeon specialty noted between those requiring transfusion and those that did not (P = 0.988).

The NSQIP database allowed for identification of the time-point of transfusion (Table II). Only 42% of transfusions happened on the day of the operation, while the majority happened in the postoperative period as far out as postoperative day 4.

Table 2.

Timing of transfusion for entire cohort. A total of 276 patients were transfused, which is 1.7% of the entire cohort. 42% of these patients were transfused on the day of the operation. Lack of deep granularity of the data prevent from determining the exact time-point of transfusion, i.e. intraoperative versus early postoperative. The majority of patients (58%) were transfused postoperatively beginning on postoperative day 1 and extending beyond postoperative day 4.

| Postoperative Day of Transfusion | Number of Patients Transfused N (%) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 115 (42) |

| 1 | 109 (40) |

| 2 | 39 (14) |

| 3 | 11 (4) |

| 4+ | 1 (1) |

| Unknown Date | 1 (1) |

The model derivation set (N = 8,039) and validation sets (N = 8,004) were compared in Table III.

Table 3.

Comparison of model and validation set. The prediction model is created using the development data set. The total data set was split via random assignment to either the development or validation data set. The groups are generally similar.

| All | Missing Data | Development Set | Validation Set | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 16043 (% of present data) | N (% of total) | N = 8039; 50.1% | N = 8004; 49.9% | ||

| Age [years; mean ± SD] | 71.2 ± 9.3 | 0 (0) | |||

| Female | 6425 (40) | 0 (0) | 3194 (20) | 3231 (20) | 0.411 |

| Race | 793 (5) | 0.605 | |||

| – White | 14217 (89) | 7098 (88) | 7119 (94) | ||

| – Black | 681 (4) | 354 (4) | 327 (4) | ||

| – Asian | 277 (2) | 146 (2) | 131 (2) | ||

| – Other | 75 (1) | 28 (0) | 37 (0) | ||

| Asymptomatic Neurologic Symptom Status* | 4064 (66) | 9898 (62) | 2024 (66) | 2040 (67) | 0.518 |

| Physiologic High Risk* | 254 (4) | 9848 (61) | 124 (4) | 130 (4) | 0.654 |

| Anatomic High Risk* | 698 (11) | 9842 (61) | 333 (11) | 365 (12) | 0.148 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 143 (1) | 0 (0) | 78 (55) | 65 (46) | 0.314 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 4839 (30) | 0 (0) | 2331 (29) | 2508 (31) | 0.001 |

| Smoker | 4535 (28) | 0 (0) | 2296 (29) | 2239 (28) | 0.41 |

| Dependent Functional Status | 417 (3) | 66 (0) | 206 (3) | 211 (3) | 0.804 |

| Dyspnea | 2420 (15) | 0 (0) | 1228 (15) | 1192 (15) | 0.508 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 1808 (11) | 0 (0) | 917 (11) | 891 (11) | 0.583 |

| Hemodialysis Dependence | 153 (1) | 0 (0) | 79 (1) | 74 (1) | 0.745 |

| Preoperative Open Wound | 149 (1) | 0 (0) | 81 (1) | 68 (1) | 0.323 |

| Chronic Steroid Use | 481 (3) | 0 (0) | 251 (3) | 230 (3) | 0.379 |

| Bleeding Disorder | 3275 (20) | 0 (0) | 1625 (20) | 1650 (21) | 0.531 |

| Preoperative > Transfusion 4 units | 28 (0) | 0 (0) | 16 (0) | 12 (0) | 0.571 |

| ASA Class | 0 (0) | 0.779 | |||

| – I | 20 (0) | 10 (0) | 10 (0) | ||

| – II | 1019 (6) | 516 (6) | 503 (6) | ||

| – III | 12575 (78) | 6309 (79) | 6266 (78) | ||

| – IV | 2418 (15) | 1200 (15) | 1218 (15) | ||

| – V | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0) | ||

| – None | 9 (0) | 4 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Preoperative Antiplatelet Agent* | 5649 (35) | 9797 (61) | 2825 (90) | 2824 (91) | 0.389 |

| Preoperative Statin* | 5014 (80) | 9792 (61) | 2507 (80) | 2507 (80) | 0.612 |

| Preoperative Beta Blocker* | 3474 (34) | 9819 (61) | 1718 (55) | 1756 (57) | 0.16 |

| BMI > 30 kg/m2 | 5374 (34) | 71 (0) | 2693 (33) | 2681 (33) | 0.987 |

| Hematocrit [mean ± SD] | 39.7 ± 4.7 | 595 (4) | 39.7 ± 4.7 | 39.7 ± 4.7 | 0.97 |

| Hematocrit < 30 | 399 (3) | 595 (4) | 209 (3) | 190 (3) | 0.389 |

| Serum Creatinine > 1.2 g/dL | 3930 (25) | 592 (4) | 1900 (25) | 2030 (26) | 0.007 |

Independent predictors of transfusion requirement for the model derivation set are shown in Table IV. Anemia, specifically hematocrit level less than 30%, was identified as the strongest predictor (OR: 57.1; 95%CI: 29.5–110.7) followed by history of congestive heart failure (OR: 2.8; 95%CI: 1.1–7.1), dependent functional status (OR: 2.7; 95%CI: 1.5–5.0), preoperative coagulopathy (OR: 2.5; 95%CI 1.7–3.6) and preoperative creatinine elevation > 1.2 mg/dl (OR: 2.3; 95%CI: 1.6–3.3). It thus appears that a transfusion event is less likely to be triggered by an intra-operative hemorrhage as it is by pre-existing anemia. Interestingly obesity with a BMI > 30 kg/m2 (OR: 0.5; 95%CI: 0.3–0.7) was protective.

Table 4.

Independent predictors of transfusion. Multivariable logistic regression analysis identified several parameters. The strongest predictor was severe anemia with hematocrit level below 30% followed by congestive heart failure, dependent function status, preoperative coagulopathy and creatinine elevation > 1.2 mg/dl. Intriguingly, BMI > 30 kg/m2 was protective. These data were the basis for the development of a risk prediction model with a c-statistic for discrimination of 0.81. Model score points are shown for each predictor.

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Model Score | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI > 30 kg/m2 | 0.46 | 0.29 – 0.70 | −2 |

| Dependent Functional Status | 2.7 | 1.5 – 5.0 | 2 |

| Female | 1.6 | 1.1 – 2.4 | 1 |

| Hematocrit Level | |||

| < 30 % | 57.1 | 29.5 – 110.7 | 8 |

| 30–40 % | 5.7 | 3.1 – 10.3 | 4 |

| 40+ % | reference | – | 0 |

| History of Congestive Heart Failure | 2.8 | 1.1 – 7.1 | 2 |

| Preoperative Coagulopathy | 2.5 | 1.7 – 3.6 | 2 |

| Preoperative Creatinine > 1.2 mg/dl | 2.3 | 1.6 – 3.3 | 2 |

| Preoperative Dyspnea | 2 | 1.3 – 3.0 | 1 |

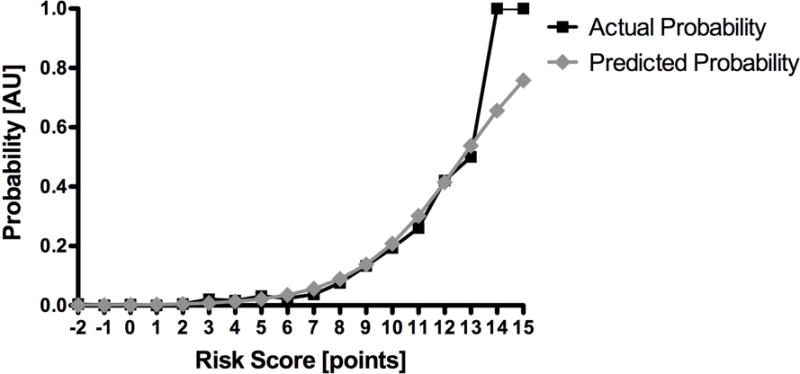

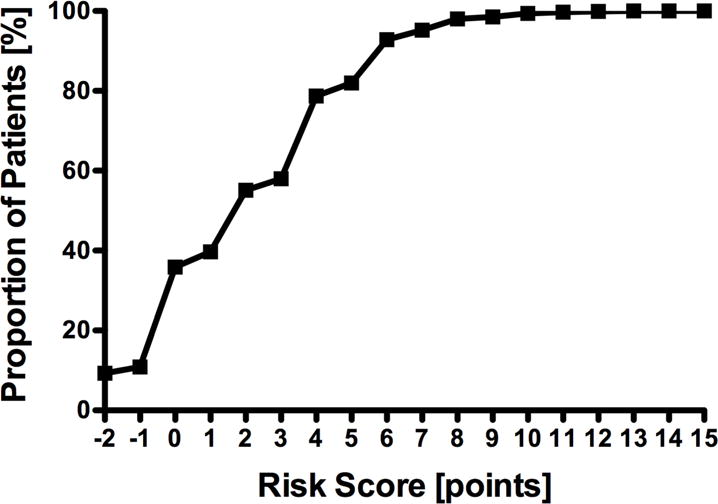

A risk score was generated based on the model with points given according to the values shown in Table IV. Although not statistically significant, there is a less precise fit at higher points of the risk score, possibly due to the few patients at risk to generate the model. Logistic regression utilizing the risk score for the training set showed a c-statistic of 0.85, a non-significant Hosmer-Lemeshow test result (P = 0.14) and a Brier score of 0.02. When applied to the validation set the model demonstrated a c-statistic of 0.81 and a Brier score of 0.02. Agreement between the predicted probability of transfusion generated by the risk score and the actual probability of transfusion in the validation set is shown in Figure 1. Table V demonstrates the actual and predicted risk of transfusion per point of assigned risk score. The cumulative proportion of patients in the validation set by risk score is demonstrated in Figure 2 with 93% of patients having a risk score of 6 or less, corresponding to an individual predicted transfusion risk of 5% or less.

Figure 1.

Accuracy of risk score model. There is a high degree of agreement between the predicted probability of transfusion generated by the risk score and the actual probability of transfusion in the validation set. There is, however, a less precise fit at higher points of the risk score, especially for 14 and 15 points, which is not statistically significant. This is likely due to few patients at risk at these points.

Table 5.

Actual and predicted risk of transfusion by risk score. Using the independent predictors of transfusion and their corresponding risk score points as shown in table 4, actual and predicted event rates are displayed for each point on the risk score from −2 to 15.

| Score | Acutal Risk | Predicted Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Points | % | % |

| −2 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| −1 | 0 | 0.11 |

| 0 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| 1 | 0 | 0.3 |

| 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 3 | 2.1 | 0.8 |

| 4 | 1.6 | 1.3 |

| 5 | 3.1 | 2.2 |

| 6 | 2.4 | 3.5 |

| 7 | 3.7 | 5.6 |

| 8 | 7.6 | 8.9 |

| 9 | 13.3 | 13.8 |

| 10 | 19.4 | 20.8 |

| 11 | 26.1 | 30.1 |

| 12 | 42.1 | 41.5 |

| 13 | 50 | 53.8 |

| 14 | 100 | 65.6 |

| 15 | 100 | 75.8 |

Figure 2.

Cumulative proportion of patients. Patients in the validation set are displayed according to their risk score. 93% of patients have a risk score of 6 or less, corresponding to an individual predicted transfusion risk of 5%.

The subset of cases from the vascular targeted NSQIP module numbered 6287 of which 1.3% (N = 80) required transfusion. Independent predictors of transfusion for the vascular targeted NSQIP subset included dependent functional status (OR: 3.46, 95%CI: 1.58–7.59), presence of dyspnea (OR: 2.29, 95%CI: 1.62–4.50), bleeding disorder such as vitamin K deficiency, hemophilias, thrombocytopenia or chronic anticoagulation therapy that has not been discontinued prior to surgery (OR: 2.89, 95%CI: 1.78–4.71), obesity (OR: .31, 95%CI: .16–.60), hematocrit level less than 30% with reference hematocrit greater than or equal to 40 (OR: 62.1, 95%CI: 28.27–136.41) and hematocrit between 30 and 40 (OR: 5.1, 95%CI: 2.5–10.5). Of note, symptom status, use of anti-platelet agents or anatomic high risk did not have an influence on transfusion rates.

DISCUSSION

The present study found its origin in an everyday situation in our institution’s preoperative area: a procedure for CEA was delayed because the preoperative type and screen had not been sent during the preoperative anesthesia evaluation as required per institutional guidelines. This raised the question of whether a T&S was actually indicated at all, since anecdotally transfusion during or after CEA is exceedingly rare. The present study aims to identify the true incidence of perioperative transfusion as well as identify those at increased risk for transfusion in an effort to determine a low risk group, for whom T&S can safely be avoided.

We found that transfusion overall is a rare event for patients undergoing primary CEA (1.7%; N = 276/16,043). Despite this rare event rate institutional guidelines often require the preparation of a T&S preoperatively. Saxena et al. describe their efforts to ensure timely completion of required T&S for elective surgery.6 In this effort they categorize CEA with other vascular procedures such as infrainguinal bypass grafting and abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (AAA). There is, however, sufficient evidence to suggest that CEA does not belong in the “high risk” category of surgical procedures like AAA. CEA ranks as moderate risk in the modified Johns Hopkins surgical criteria due to degree of invasiveness and chance for blood loss.1 Furthermore the cardiac risk imposed by CEA is in the moderate range, i.e. myocardial risk between 1–5%, as several large studies have demonstrated: ACAS at 1.9%, NASCET at 1.5% and most recently CREST at 2.3%.3–5 It has been shown that moderate risk procedures do not require a T&S to be preformed safely. Van Klei at al. studied the need for preoperative T&S and its potential omission in 1482 patients undergoing moderate risk procedures such as cholecystectomy and hysterectomy.15 Setting the individual transfusion risk at 5%, they could show that 50% of preoperative T&S in this patient population could safely be avoided. We found a higher degree of avoidable T&S in the studied population (93% of T&S avoided with the threshold for T&S set at a 5% transfusion rate, Fig. 2). This apparent difference could be due to the distinct cohorts that we analyzed as well as quite different transfusion rates of 19% (van Klei) vs 1.7% in the present study. Ghirardo et al. replicated these results in 3,424 patient undergoing moderate risk general surgery procedures and again found little evidence to support mandatory preoperative T&S in light of 0.32% overall RBC transfusion rate.16 Finally, Dexter et al. confirmed the threshold of 5% predicted individual transfusion risk as appropriate to trigger preoperative T&S.17 Beyond institutional requirements another reason that T&S are oftentimes ordered is that surgeons tend to over-utilize laboratory testing, possibly for medico-legal reasons or in the case of vascular surgeons, due to habituation to high risk procedures.18

One could argue that this 5% threshold to trigger a preoperative T&S is arbitrarily set but the literature supports its clinical value of being cost-effective and safe.15–18 Another argument is that the threshold of 5% predicted individual transfusion risk is inappropriately high, especially in light of an overall actual transfusion rate of 1.7% in the whole population. Subsets of this population stratified by risk, however, have very different transfusion rates. For the individual patient the event rate is either 0% or 100% transfusion. The 5% predicted individual risk refers to the a priori risk based on the score. The majority of patients has a predicted risk below 5%, and indeed patients with a score of 6 or less in the validation set are very rarely transfused, (1.0%, N = 75/7,355, Figure 1). Should the predicted risk exceed 5%, the patients are accordingly more likely transfused. This “high risk” group with a score ≥ 7 has an actual transfusion rate of 8.1% (63/511 patients of the validation set).

We found that the majority of RBC transfusions (58%) occurred on postoperative day one or later. These transfusions were not triggered by acute, intraoperative hemorrhage but presumably by set transfusion thresholds. The CEA seems to be the time-point when someone checked the hematocrit level and subsequently transfused the patient. The fact that a preoperative hematocrit level below 30% is the strongest predictor for transfusion supports that notion. This practice is not necessarily benign. During the last two decades several studies have called into question the prevalent practice of allogeneic RBC transfusion for a liberal hemoglobin (Hgb) threshold (Hgb < 10 g/dL) in favor of a restrictive threshold (Hgb < 7 g/dL). Adams and Lundy proposed the ‘10/30 rule’, i.e. transfusion if hemoglobin level < 10 g/dL or hematocrit < 30%, as early as 1942 to treat the reduced oxygen delivery in situations of hemorrhage and anemia.19 Several landmark papers, however, delivered very strong evidence that a restrictive transfusion strategy is associated with fewer RBC transfusions and improved in-hospital mortality.20–22

We used our data to develop a risk prediction model that could guide further preoperative T&S for patients undergoing CEA. The proposed model showed that 93% of all preoperative T&S can be avoided using the individual predicted transfusion risk of 5% as a threshold (Figure 2).17 This offers substantial cost saving potential while maintaining patient safety at current standards; a major benefit in the current healthcare climate of limited resources. Based on our institutional cost of $350 for a standard T&S, the potential savings could amount to more than $5.2M in the studied NSQIP population.

One can argue that omitting preoperative T&S puts patients at risk in emergent intraoperative situations. This is a very rare event: 0.7% of patients were transfused on the day of the operation, and even less intraoperatively. The use of O-negative blood allows for rapid patient stabilization while a T&S and crossmatch is performed within 30–60 minutes. O-negative blood is screened for the presence of the most significant non-ABO antibodies. The prevalence of irregular erythrocyte antibody ranges between 1.9% and 2.5% in the general population, the risk of transfusion-related adverse reactions is equally low. Rapid administration of O-negative blood acceptably addresses any hemodynamic instability in an emergency situation with evidence that no patient has died from a transfusion complication and the rate of seroconversion in Rh-negative patients is low.16

The findings of this study must be interpreted in the context of its retrospective case-control study design. While the use of a large database studies offers increased sample size and standardized data collection, this is gained at the expense of granular clinical detail. Specifically, the NSQIP fails to capture the precise clinical circumstances related to transfusion administration such as patient symptoms, vital signs, intraoperative blood loss or hemoglobin/hematocrit levels. Further, missing data within the NSQIP and the minority of patients included in the vascular targeted module precluded the consideration of certain parameters in our multivariable model. Yet, subset analysis of the vascular targeted cases failed to demonstrate an association between either symptom status or antiplatelet usage and transfusion. However, despite these limitations, our study does identify patient characteristics associated with transfusion administration, which may be considered by the surgeon in addition to the clinical parameters noted above to augment clinical decision making. These findings may now be subjected to further testing with either future NSQIP data or other clinical data sets.

CONCLUSION

Transfusion in patients undergoing CEA is a rare event in the NSQIP population calling into question the need for the common practice of obtaining a preoperative T&S. A novel risk score can reliably predict transfusion. Using this model a low-risk population is identified, in whom preoperative T&S can safely be omitted while providing a substantial cost saving opportunity without compromise of patient care.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This study was presented at the 43rd Annual Symposium of the Society for Clinical Vascular Surgery (SCVS) in Miami, FL (March 29 – April 02, 2015).

References

- 1.Donati A. A new and feasible model for predicting operative risk. Br J Anaesth. 2004 Sep 1;93(3):393–399. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carson JL, Duff A, Poses RM, Berlin JA, Spence RK, Trout R, et al. Effect of anaemia and cardiovascular disease on surgical mortality and morbidity. The Lancet. 1996 Oct;348(9034):1055–1060. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)04330-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hobson RW, Weiss DG, Fields WS, Goldstone J, Moore WS, Towne JB, et al. Efficacy of carotid endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid stenosis. The Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993 Jan 28;328(4):221–227. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301283280401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1991 Aug 15;325(7):445–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108153250701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brott TG, Hobson RW, Howard G, Roubin GS, Clark WM, Brooks W, et al. Stenting versus endarterectomy for treatment of carotid-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 1;363(1):11–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saxena S, Nelson JM, Osby M, Shah M, Kempf R, Shulman IA. Ensuring timely completion of type and screen testing and the verification of ABO/Rh status for elective surgical patients. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007 Apr;131(4):576–581. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-576-ETCOTA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Blood Management. Practice guidelines for perioperative blood management: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Blood Management. Anesthesiology. 2015 Feb;122(2):241–275. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Couture DE, Ellegala DB, Dumont AS, Mintz PD, Kassell NF. Blood use in cerebrovascular neurosurgery. Stroke. 2002 Apr;33(4):994–997. doi: 10.1161/hs0402.105296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. 2013 Oct;:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shiloach M, Frencher SK, Steeger JE, Rowell KS, Bartzokis K, Tomeh MG, et al. Toward robust information: data quality and inter-rater reliability in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2010 Jan;210(1):6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz MH. Multivariable Analysis: A Practical Guide for Clinicians and Public Health Researchers. 3rd. Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iannuzzi JC, Young KC, Kim MJ, Gillespie DL, Monson JRT, Fleming FJ. Prediction of postdischarge venous thromboembolism using a risk assessment model. J Vasc Surg. 2013 Oct;58(4):1014–1020.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iannuzzi JC, Chandra A, Kelly KN, Rickles AS, Monson JR, Fleming FJ. Risk score for unplanned vascular readmissions. J Vasc Surg. 2014 May;59(5):1340–7.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.11.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sullivan LM, Massaro JM, D’Agostino RB., Sr Tutorial in biostatistics: presentation of multivariate data for clinical use: the Framingham Study risk score functions. Stat Med. 2004;23:1631–1660. doi: 10.1002/sim.1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Klei WA, Moons KG, Leyssius AT, Knape JT, Rutten CL, Grobbee DE. A reduction in type and screen: preoperative prediction of RBC transfusions in surgery procedures with intermediate transfusion risks. Br J Anaesth. 2001 Aug;87(2):250–257. doi: 10.1093/bja/87.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghirardo SF, Mohan I, Gomensoro A, Chorost MI. Routine Preoperative Typing and Screening: A Safeguard or a Misuse of Resources. JSLS. 2010;14(3):395–398. doi: 10.4293/108680810X12924466007241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dexter F, Ledolter J, Davis E, Witkowski TA, Herman JH, Epstein RH. Systematic Criteria for Type and Screen Based on Procedure’s Probability of Erythrocyte Transfusion. Anesthesiology. 2012 Apr;116(4):768–778. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31824a88f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hadler R, Liu R. When Should a Type and Screen not be Ordered Preoperatively. J Anesthe Clinic Res. 2013;4:272. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carson JL, Carless PA, Hebert PC. Transfusion thresholds and other strategies for guiding allogeneic red blood cell transfusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD002042. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002042.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hébert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. N Engl J Med. 1999 Feb 11;340(6):409–417. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carson JL, Terrin ML, Noveck H, Sanders DW, Chaitman BR, Rhoads GG, et al. Liberal or restrictive transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011 Dec 29;365(26):2453–2462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Villanueva C, Colomo A, Bosch A, Concepción M, Hernandez-Gea V, Aracil C, et al. Transfusion Strategies for Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jan 3;368(1):11–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]