Introduction

The 2013-2016 West African Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak has been the largest in history with 28,616 cases and 11,310 deaths in the highest transmission countries of Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia.1 Reports of uveitis have emerged in EVD survivors.2-3 Herein we discuss clinical features, multimodality imaging, and long-term management of aggressive, sight-threatening panuveitis, in an EVD survivor, providing insight into the pathogenesis of this condition.

Case Report

Acute Ebola virus disease and early post-Ebola syndrome

A 43-year-old physician developed EVD in Kenema, Sierra Leone. After 40 days of hospitalization at Emory University, he was discharged with serum and urine testing negative by quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assay for EBOV RNA.4 One month after discharge, he experienced blurred vision, sacroilitis, enthesitis, and word-finding difficulties. Ophthalmic evaluation showed visual acuities of 20/15 in both eyes and multiple peripheral chorioretinal scars with hypopigmented haloes bilaterally, consistent with inactive chorioretinitis requiring no intervention (Supplemental Figure 1).

Acute hypertensive anterior uveitis

Fourteen weeks after EVD diagnosis, the patient presented with acute, left hypertensive anterior uveitis with visual acuity of 20/20 and intraocular pressure (IOP) of 44 mmHg in the left eye.2 Treatment was initiated with topical prednisolone acetate 1% (Pred Forte 1%) 4 times daily, brimonidine 0.2% and dorzolamide 2%/timolol 0.5%, and acetazolamide. Serologies for syphilis, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus-1 and -2, and Toxoplasma gondii. HLA-B27 was negative.

Left anterior chamber paracentesis yielded aqueous humor positive for EBOV by qRT-PCR with a cycling threshold of 18.7 and a positive EBOV culture. Pre- and 24-hours post-procedure, conjunctival swab and tear film tested negative for EBOV RNA.2

Anterior scleritis, and intermediate uveitis

On day 5 of the acute ocular illness, left visual acuity declined to 20/60 and the IOP was 15 mmHg. Diffuse anterior scleritis and intermediate uveitis prompted addition of oral prednisone 80 mg, with the topical Pred Forte 1% every 2 hours, timolol 0.5%, and atropine 1% (Supplemental Figure 2).

Left visual acuity declined to 20/150 at day 6 of illness, and examination revealed grade 2+ AC cell, a 0.5 mm hypopyon, and grade 1-2+ vitreous haze. OCT scan showed mild left retinal thickening (Supplemental Figure 2).

Despite symptomatic improvement, left visual acuity worsened to 20/250 at day 9, and IOP declined to 6 mmHg. Corneal edema followed hypotony, with grade 2+ AC cell and grade 3+ vitreous haze (Supplemental Figure 2). Difluprednate 0.05% every 2 hours was initiated.

Optic neuropathy, and panuveitis

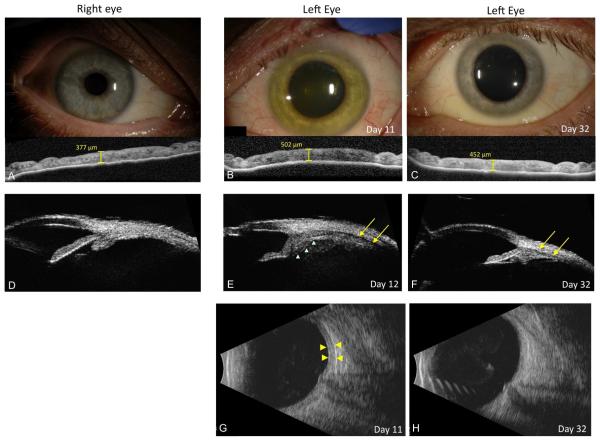

Left visual acuity deteriorated to 20/500 and IOP decreased to 2 mmHg at day 10. A left relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) developed, indicating optic neuropathy. Iris heterochromia developed at day 11, with a change from blue to green (Figure 1). Left anterior segment OCT (AS-OCT) revealed iris stromal thickening (502 μm) when compared to the right (376 μ m). Ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) showed ciliary body edema. A dense grade 3+ vitreous haze persisted, prompting B-scan ultrasound, which revealed shallow peripheral, choroidal effusions and optic nerve head edema (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Anterior segment photographs and digital imaging.

(A) Slit lamp photograph of right eye with corresponding anterior segment OCT at baseline shows iris thickness of 377 μm. (B) Slit lamp photograph and anterior segment OCT at day 11 show a green iris color with iris thickening at 502 μm. (C) By day 32, slit lamp photograph shows reversal of iris color to original blue color and corresponding decrease in iris edema to 452 μm. (D) Ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) show normal ciliary body anatomy of the right eye. (E) UBM of left eye shows ciliary body swelling (green triangles) and supraciliary/choroidal effusion (yellow areas) consistent with progressive panuveitis, choroiditis and evolving hypotony at day 12. (F) Repeat UBM shows decreased ciliary body swelling and resolution of supraciliary/choroidal effusion (yellow arrows) by day 32. (G) B-scan ultrasound shows choroidal thickening at day 11 and repeat at day 32. (H) shows resolution of choroidal thickening.

Antiviral therapy with favipiravir

Due to clinical worsening, a 21-day course of oral favipiravir (T-705, Toyoma Chemical, Japan) was initiated. After two loading doses of 2000 mg, favipiravir was administered 1200 mg twice daily. Three days after starting favipiravir (day 18 of illness), visual acuity had declined to finger counting at 2 feet and IOP was 3 mmHg. A periocular triaminolone acetonide injection (40 mg/1 ml) was administered in the Emory University Hospital Serious Communicable Diseases Unit (SCDU). A post-procedure conjunctival swab tested negative for EBOV RNA.

One day after the injection, left visual acuity was hand motions, but IOP increased to 9 mmHg. The patient was discharged on a course of favipiravir, and oral prednisone was tapered, decreasing by 10 mg/day every two weeks. Topical difluprednate 0.05% and atropine 1% were continued.

Long-term follow-up

Forty-five days after initial onset of acute ocular illness, the patient completed favipiravir and remained on oral prednisone 15 mg daily and topical difluprednate 0.05%. Visual acuity had improved to 20/15 with resolution of RAPD and IOP of 10 mmHg. Slit lamp examination showed resolved corneal edema, endothelial pigment without KP, and trace AC pigment. Posterior segment examination showed grade 0.5+ vitreous haze. The iris thickness had decreased to 452 μm by day 32, with resolution of heterochromia (Figure 1)

At one-year follow-up, left visual acuity returned to 20/20 with IOP of 11 mmHg. After 18 months, visual acuity had declined to 20/60 with development of diffuse posterior capsular cataract. Anterior uveitis was observed with diffuse stellate KP, 1+ AC cell and stable posterior segment. Repeat AC paracentesis tested negative for Ebola virus by qRT-PCR. PCR testing was also negative for CMV, HSV, and VZV DNA. Topical prednisolone acetate taper was given over four weeks with resolution of anterior uveitis.

Discussion

The clinical and multimodal imaging features of this aggressive spectrum of ophthalmic pathology highlight the mechanisms of inflammation and infection, which improved following the administration of corticosteroids and antiviral medication.

Iris heterochromia coincided with iris and ciliary body edema by AS-OCT and UBM; this was suggestive of heavy leukocyte infiltration and/or massive protein exudation related to an extreme inflammatory response associated with active EBOV replication. Immediate improvement of IOP and recovery of ciliary body anatomy following the corticosteroid injection supported the key role of appropriately timed anti-inflammatory therapy.

Although the precise role of favipiravir – a pyrazinecarboxamide derivative that inhibits viral RNA replicase5 – was unclear, our patient’s disease process worsened initially on topical and systemic corticosteroid. Following the initiation of favipiravir, a periocular corticosteroid injection was administered because of concerns for recalcitrant hypotony, ciliary body shutdown, and irreversible vision loss. The patient’s clinical improvement paralleled the anatomic reduction in iris thickening by AS-OCT.

In summary, diagnostic ophthalmic imaging highlighted the anatomic and pathologic changes that occurred during our patient’s sight-threatening panuveitis. The imaging findings suggested severe reactive inflammation in the presence of EBOV viral replication, emphasizing the need for consideration of management strategies that target infectious and inflammatory processes in post-Ebola uveitis. Potential for uveitis recurrence mandates long-term monitoring.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Baseline fundus photography and digital imaging. (A) Fundus photograph of the right eye shows clear media and a retinal opacity temporal to the optic nerve (green arrow) (B) A corresponding fluorescein angiogram image shows hyperfluorescence with staining of the retinal lesion temporal (arrow) and three small lesions nasal to the nerve. (C) Fundus photograph of the inferotemporal retina shows a hyperpigmented scar with a hypopigmented halo. (D) Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) shows retinal architectural change (green arrows) nasal the optic nerve and a fluorescein angiogram shows the location of OCT cross-section. (E) Slightly inferiorly located OCT shows outer and inner retinal architectural changes corresponding to retinal lesions.

Supplemental Figure 2. External photography, fundus photography and digital imaging. (A) Slit lamp photograph shows diffuse anterior scleritis as the anterior chamber inflammation worsened. (B) A layered hypopyon uveitis developed subsequently. (C) Corneal edema with iris heterochromia was eventually observed as the uveitis progressed. (D) Fundus photograph of the left eye at baseline shows clear media. (E) Severe vitreous inflammation developed as the patient’s disease progressed with obscuration of the optic nerve and blood vessels, eventually leading to nearly complete obscuration of the optic nerve (F). (G) A spectral domain OCT of the left eye shows normal foveal contour at baseline. (H) Macular edema developed and worsened until OCT could not longer be visualized due to vitreous inflammation (I).

Acknowledgments

Financial Support

This project was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award Number UL1TR000454 (Atlanta Clinical and Translational Science Institute), an unrestricted departmental grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc. (New York, NY) and by NIH/NEI core grant P30-EY06360 (Department of Ophthalmology, Emory University School of Medicine), an Alcon Research Institute Young Investigator Grant (Dr. Yeh), a Heed Ophthalmic Fellowship Foundation Grant, Cleveland, OH (Dr. Shantha), and a fellowship grant from the Australian Research Council (FT130101648, to Dr. Smith). Favipiravir was provided by the Department of Defense Joint Project Manager Medical Countermeasure Systems.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Meeting Presentations

American Academy of Ophthalmology Annual Meeting, “Ophthalmic manifestations of Ebola virus disease”, AAO Symposium “Ebola and the Eye: A Story of Survivors”, November 15, 2015, Las Vegas, NV

American Society of Retina Specialists Annual Meeting, “Clinical Features and Multimodality Diagnostic Imaging in Ebola Virus-Associated Panuveitis: Insights into Pathogenesis”, July 12, 2015, Vienna, Austria

American Society of Retina Specialists Annual Meeting, “Panuveitis associated with Ebola Virus Disease: Clinical Management”, July 12, 2015, Vienna, Austria

ARVO Keynote Series Closing Session: “Ebola and the Eye: A Story of Discovery and Uncertainty”, May 7, 2015, Denver, Colorado

References

- 1.Ebola situation report - 10 June 2016. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2016. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/208883/1/ebolasitrep_10Jun2016_eng.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varkey JB, Shantha JG, Crozier I, et al. Persistence of Ebola Virus in Ocular Fluid during Convalescence. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;372(25):2423–2427. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattia JG, Vandy MJ, Chang JC, et al. Early clinical sequelae of Ebola virus disease in Sierra Leone: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet. Infectious diseases. 2015 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00489-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kraft CS, Hewlett AL, Koepsell S, et al. The Use of TKM-100802 and Convalescent Plasma in 2 Patients With Ebola Virus Disease in the United States. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2015;61(4):496–502. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oestereich L, Ludtke A, Wurr S, Rieger T, Munoz-Fontela C, Gunther S. Successful treatment of advanced Ebola virus infection with T-705 (favipiravir) in a small animal model. Antiviral research. 2014;105:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Baseline fundus photography and digital imaging. (A) Fundus photograph of the right eye shows clear media and a retinal opacity temporal to the optic nerve (green arrow) (B) A corresponding fluorescein angiogram image shows hyperfluorescence with staining of the retinal lesion temporal (arrow) and three small lesions nasal to the nerve. (C) Fundus photograph of the inferotemporal retina shows a hyperpigmented scar with a hypopigmented halo. (D) Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) shows retinal architectural change (green arrows) nasal the optic nerve and a fluorescein angiogram shows the location of OCT cross-section. (E) Slightly inferiorly located OCT shows outer and inner retinal architectural changes corresponding to retinal lesions.

Supplemental Figure 2. External photography, fundus photography and digital imaging. (A) Slit lamp photograph shows diffuse anterior scleritis as the anterior chamber inflammation worsened. (B) A layered hypopyon uveitis developed subsequently. (C) Corneal edema with iris heterochromia was eventually observed as the uveitis progressed. (D) Fundus photograph of the left eye at baseline shows clear media. (E) Severe vitreous inflammation developed as the patient’s disease progressed with obscuration of the optic nerve and blood vessels, eventually leading to nearly complete obscuration of the optic nerve (F). (G) A spectral domain OCT of the left eye shows normal foveal contour at baseline. (H) Macular edema developed and worsened until OCT could not longer be visualized due to vitreous inflammation (I).