Abstract

Objective

To ascertain demographic and clinical characteristics of maternal deaths from self-harm (accidental overdose or suicide) in order to identify opportunities for prevention.

Methods

We report a case series of pregnancy-associated deaths due to self-harm in the state of Colorado between 2004 and 2012. Self-harm deaths were identified from several sources, including death certificates. Birth and death certificates along with coroner, prenatal care and delivery hospitalization records were abstracted. Descriptive analyses were performed. For context, we describe demographic characteristics of women with a maternal death from self-harm and all women with live births in Colorado.

Results

Among the 211 total maternal deaths in Colorado over the study interval, 30% (n=63) resulted from self-harm. The pregnancy-associated death ratio from overdose was 5.0 (95% CI 3.4, 7.2) per 100,000 live births and from suicide 4.6 (95% CI 3.0, 6.6) per 100,000 live births. Detailed records were obtained for 94% (n=59) of women with deaths from self-harm. Deaths were equally distributed throughout the first postpartum year (mean 6.21 ± 3.3 months postpartum) with only 6 maternal deaths during pregnancy. Seventeen percent (n=10) had a known substance use disorder. Prior psychiatric diagnoses were documented in 54% (n=32) and prior suicide attempts in 10% (n=6). While half (n=27) of the women with deaths from self-harm were noted to be taking psycho-pharmacotherapy at conception, 48% of them discontinued the medications during pregnancy. Fifty women had toxicology testing available; pharmaceutical opioids were the most common drug identified (n=21).

Conclusion

Self-harm was the most common cause of pregnancy-associated mortality with most deaths occurring in the postpartum period. A four-pronged educational and program building effort to include women, providers, health care systems, and both governments and organizations at the community and national level may allow for a reduction in maternal deaths.

Introduction

Reduction of maternal mortality has become a priority in the United States and other nations.1,2 As a consequence of collaborative efforts between the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and others, common causes of pregnancy-related mortality such as hemorrhage, hypertension, venous thromboembolism, and infection, are now targeted with specific action plans and safety bundles delineating appropriate clinical care.2 In February 2016, the Council on Patient Safety in Women's Healthcare released a safety bundle for maternal mental health which summarizes screening strategies and suggested responses when disorders are identified.3

Despite these advances, there has been relatively little focus on maternal deaths resulting from self-harm, specifically those related to accidental overdose and suicide. This lack of focus on deaths from self-harm may be, in part, a result of barriers to screening and treatment for psychiatric disorders.4,5 The lack of recognition of deaths from self-harm as a significant contributor to maternal death may also be a result of the exclusion of accidental or incidental deaths occurring during pregnancy or in the first year postpartum from reporting to the CDC as pregnancy-related mortality.6 The first steps in prevention include gaining a better understanding the characteristics of women with a maternal death resulting from self-harm.

The objectives of this study were to define rates of maternal deaths from self-harm in Colorado, describe the demographic and clinical characteristics of women who died, and assess risk factors for these deaths to identify opportunities for prevention.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a case study of all women with pregnancy-associated deaths (death during pregnancy or within 1 year postpartum from any cause) from self-harm in Colorado from January 1, 2004 through December 31, 2012. Deaths due to suicide (regardless of cause, including suicide by poisoning) and drug overdoses (unintentional poisonings and poisonings of undetermined intent) were categorized broadly as deaths from “self-harm” for the purposes of this study, as it is often difficult for the coroner and Colorado Maternal Mortality Review Committee (a panel of experts including obstetrician–gynecologists, perinatologists, substance use disorder experts, injury prevention experts, psychiatrists and a coroner) to accurately classify these deaths by intent even after reviewing all available documentation.7,8 This approach was also supported by prior literature demonstrating an over-classification of overdoses as accidental rather than suicide.7 Cases of overdoses are not classified as suicide by a medical examiner or coroner unless there is clear evidence indicating an intention to take one's own life and deliberate means. Often this must be corroborated by other evidence of suicide such as a suicide note, known suicidal ideations, or a prior attempt.7 When cases of maternal death by accidental overdose are reviewed by mental and behavioral health experts on the Colorado Maternal Mortality Review Committee, it is often concluded that the death may have been intentional despite a documented manner of death of accidental. Thus, these outcomes were combined for the purposes of this study.

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was sought from both the Colorado Multiple IRB (as data were to be analyzed at the University of Colorado) and the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment IRB (as data were abstracted at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment). This project was deemed exempt by the Colorado Multiple IRB since all subjects were deceased and approved by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment IRB.

Process of Identifying Maternal Deaths in Colorado

Each year, Colorado maternal deaths are identified by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment from three sources: (1) International Classification of Disease (ICD) -10 “O” codes on the death certificate, indicating that the cause of death was related to or aggravated by pregnancy, childbirth or the puerperium; (2) selection of a pregnancy field on the Colorado death certificate (includes ‘pregnant at the time of death’, ‘not pregnant, but pregnant within 42 days of death’, and ‘not pregnant, but pregnant 43 days to 1 year before death’); and (3) matching of all state death certificates among females age 8-65 years to the reported name of the mother on all live birth and fetal death certificates during the same year as the death or the year prior.

After identifying possible cases of maternal death by these methods, Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment staff and members of the Colorado Maternal Mortality Review Committee excluded cases which did not meet the accepted definition of a pregnancy-associated death (death during pregnancy or within 1 year postpartum from any cause).9 The Maternal Mortality Review Committee categorized all pregnancy-associated deaths and did not limit our review to the CDC definition of pregnancy-related mortality which excludes deaths from accidental or incidental causes.6

Cases of maternal death from self-harm were identified from all maternal deaths in Colorado over the study time period. Deaths from self-harm were identified from death certificate documentation of a suicide or accident, with a secondary classification of overdose. Accidental overdoses included poisonings from illicit drugs and medications. If the manner of death was documented as unknown or natural on the death certificate, we relied on the determination of the Colorado Maternal Mortality Review Committee that the death was a result of overdose or suicide.

For identified maternal deaths from self-harm, three written contacts were made by Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment staff to obtain records from the coroner, primary prenatal care provider, and hospital of delivery and/or death. Records requested included: birth certificate, death certificate, labor and delivery records, prenatal and postpartum care medical records (including social work and psychiatric records, when available), autopsy report, toxicology testing, coroner's report, and law enforcement report (if applicable).

All available self-harm death records were reviewed by a medical professional trained in detailed data abstraction using a data abstraction instrument developed by the investigators. Data abstraction items included sociodemographics (race, ethnicity, maternal age, marital status, type of residence, insurance status, weeks of gestation or number of months postpartum at time of death), psychiatric history (documented psychiatric diagnosis, current psycho-pharmacotherapy, discussion about continuation of pharmacotherapy during pregnancy, prior suicide attempts, and current or prior substance use), social history (involvement of the father of the child, living situation, employment status), and clinical history (preterm delivery, adverse obstetrical events).

Drugs identified on toxicology testing at the time of death were categorized by drug class as opioids, alcohols, benzodiazepines, other sedatives or hypnotics, antidepressants, amphetamines, muscle relaxants, cannabinoids, acetaminophen, anesthetics, antipsychotics, barbiturates, or phencyclidine. Illegal drugs (cocaine, heroin, phencyclidine) were combined into an illicit drug category for further descriptive analysis. Of note, medicinal marijuana was legal in Colorado for a portion of the study period. Marijuana was not fully legalized for recreational use until after the study period. However, given the overlap with legalization of medicinal marijuana, cannabinoids were not included as illicit drugs. Prescription opioids (including methadone), benzodiazepines, sedatives/hypnotics, antidepressants and muscle relaxants were grouped as pharmaceutical medications.

All data were abstracted into a secure web-based Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) application.10

Data from live births were extracted from state birth certificate data by Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment staff. While maternal deaths and live births are not mutually exclusive, state-wide data on all live births over the study time period were collected to provide context for our detailed data abstraction including the frequency and percent of women in each category of residence (urban, rural, frontier, unknown), race, marital status, and insurance status.

Descriptive data (frequencies, percentages) for maternal deaths from self-harm were generated. Death ratios were calculated over the number of live births per year. Categorical demographic characteristics were summarized for women with a maternal death from drug overdose or suicide, and for all women with a live birth in Colorado over the same time period. All analyses were completed in SAS 9.4, and graphics were created in GraphPad Prism 6.0.

Results

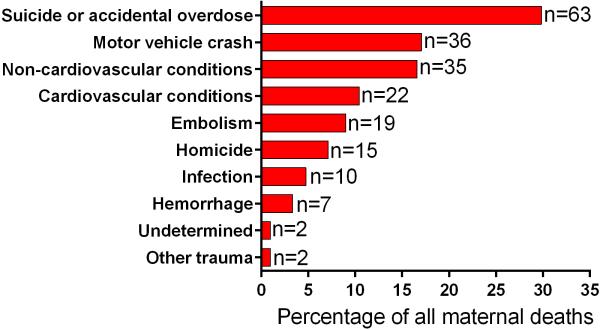

There were 211 maternal deaths in Colorado over the 9-year study period (January 1, 2004 through December 31, 2012), of which 63 (30%) were classified as maternal death by self-harm (accidental overdose or suicide). Self-harm was the leading cause of maternal death in Colorado (Figure 1). From 2004 to 2012, the overall pregnancy-associated mortality ratio was 34.4 (95% CI 29.9, 39.3) per 100,000 live births; the mortality ratio from accidental overdose was 5.0 (95% CI 3.4, 7.2) per 100,000 live births and from suicide was 4.6 (95% CI 3.0, 6.6) per 100,000 live births.

Figure 1.

Maternal deaths in Colorado from 2004-2012 (N=211) classified by cause. The x-axis delineates the percentage of maternal deaths in each category stated on the y-axis, with the frequency in each category provided at the end of each bar. Classifications are mutually exclusive.

Detailed medical records were obtained for 94% (n=59) of women who died of accidental overdoses (n=31) or suicide (n=28). The manner of death on the death certificate was accidental with a sub-classification of drug overdose in 26 cases. There were 5 additional cases for which the manner of death on the death certificate was unknown that were subsequently classified as accidental overdose by the Colorado Maternal Mortality Review Committee. In all of these cases, there was evidence of overdose by toxicology testing.

The manner of death was documented on the death certificate as suicide in 26 cases. Among the women with suicide documented as the manner of death, the most common means were further sub-classified as asphyxia by hanging (n=10), penetrating trauma (gunshot wound or stab wound, n=8), and intentional overdose (n=5). There were two cases in which suicide was not documented on the death certificate but the coroner and police report indicated that the death was the result of suicide; the Colorado Maternal Mortality Review Committee classified these as suicides and they were included in the study. No cases of infanticide were documented in association with maternal death from self-harm.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the maternal deaths due to accidental overdose and suicide are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Women with Maternal Deaths from Accidental Overdose or Suicide in Colorado from 2004-2012

| All Cases n=59 | Self-Harm Maternal Deaths (n=59) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic‡ | Accidental Overdose (n=31) | Suicide (n=28) | |

| Maternal age at death, mean ± SD | 27.6 ± 5.5 | 28.2 ± 5.70 | 26.9 ± 5.17 |

| Gravidity, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 11 (19.3) | 5 (16.1) | 6 (23.1) |

| 2 | 13 (22.8) | 7 (22.6) | 6 (23.1) |

| 3 | 13 (22.8) | 7 (22.6) | 6 (23.1) |

| 4 or more | 20 (35.1) | 12 (38.7) | 8 (30.8) |

| Marital status at time of death, n (%) | |||

| Married | 28 (47.5) | 13 (41.9) | 15 (53.6) |

| Single | 14 (23.7) | 9 (29.0) | 5 (17.9) |

| Divorced | 8 (13.6) | 3 (9.7) | 5 (17.9) |

| Separated | 1 (1.7) | 1 (3.2) | 0 ( 0.0) |

| Not married but living with partner | 7 (11.9) | 5 (16.1) | 2 (7.1) |

| Other | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.6) |

| Employment status at time of delivery, n (%) | |||

| Employed | 11 (18.6) | 4 (12.9) | 7 (25.0) |

| Unemployed | 38 (64.4) | 23 (74.2) | 15 (53.6) |

| Unknown | 10 (17.0) | 4 (12.9) | 6 (21.4) |

| Psychiatric diagnosis†, n(%) | |||

| Depression | 21 (35.6) | 11 (35.5) | 10 (35.7) |

| Anxiety | 14 (23.7) | 11 (35.5) | 3 (10.7) |

| Bipolar | 7 (11.9) | 5 (16.1) | 2 ( 7.1) |

| Schizophrenia | 3 (5.1) | 2 ( 6.5) | 1 ( 3.6) |

| Postpartum psychosis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 5 (8.5) | 3 ( 9.7) | 1 ( 3.6) |

| Documentation of involvement of the father of the pregnancy, n (%) | 41 (69.5) | 18 (58.1) | 23 (82.1) |

| Domesticviolence (DV),n (%) | |||

| Current DV reported in prenatal records | 3 (5.1) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (7.1) |

| History of DV | 11 (18.6) | 4 (12.9) | 7 (25.0) |

| Denies current or history of DV | 30 (50.9) | 18 (58.1) | 12 (42.9) |

| Unknown | 15 (25.4) | 8 (25.8) | 7 (25.0) |

Race, residence, and insurance status are reported in Table 2.

Some women had more than one recorded psychiatric diagnosis.

Toxicology results were available from 50 (84.7%) of the decedents: a single drug or medication was identified in 12 (24.0%), two drugs or medications were identified in 10 (20.0%), three or more drugs or medications were identified in 22 (44.0%). No drugs or medications were identified in toxicology testing from six decedents (12.0%). Pharmaceutical medications were most commonly identified, with 27 (54.0%) of the decedents with a positive toxicology test for a medication, and 14 (28.0%) with illicit drugs, including 10 with cocaine or cocaine metabolites and 4 with heroin (6-monoacetyl-morphine) or a heroin metabolite (morphine with known recent heroin use).

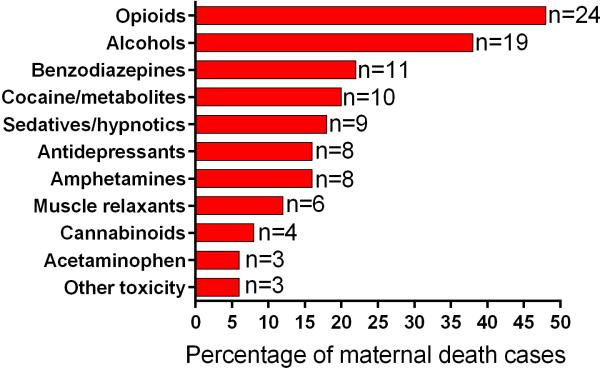

Among the 50 women with toxicology testing available, the most commonly detected class of drugs was opioids. In 21 (42.0%) cases pharmaceutical opioids were detected. In 3 cases, heroin or heroin metabolites were detected with no other opioids. In almost all cases of a pharmaceutical opioid overdose, there was documentation of a recent prescription for opioids, a known opioid use disorder, or empty opioid pill bottles found at the scene of the death. There was only one case in which the coroner's report documented that opioids were “bought on the street”; in all other cases, the women were thought to have been prescribed opioids. Classes of drugs detected on toxicology screening are reported in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Frequency of drugs and pharmaceuticals detected on toxicology testing during autopsy (n=50, toxicology testing not performed in n=9). Toxicology testing did not find any positive results for anesthetics, antipsychotics, barbiturates, or phencyclidine. Opioids include heroin and pharmaceutical opioids (including methadone). Frequencies in figure are not mutually exclusive.

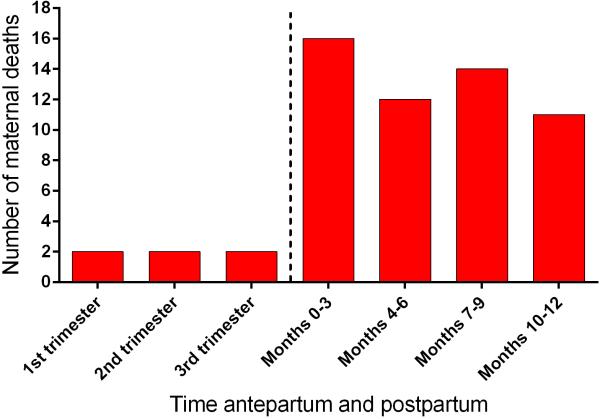

Deaths were equally distributed throughout the first postpartum year (mean 6.21 ± 3.3 months postpartum) with only 6 maternal deaths during pregnancy (Figure 3). The deaths during pregnancy occurred on average at 19.2 ± 11.6 weeks gestation, with the earliest occurring at approximately 5 weeks gestation and the latest occurring at 35 weeks gestation.

Figure 3.

Temporal distribution of maternal deaths from self-harm by trimester of pregnancy and number of months postpartum. Relatively few cases occurred during the pregnancy.

Eighty-one percent (n=48) of the 59 included women with maternal deaths from self-harm had prenatal records available for review by the study team. Three of the 59 women did not have prenatal care as documented at the time of delivery. The remaining 8 women in the case study may have had prenatal care, but we were unable to obtain antenatal records from the primary obstetrician despite three attempts. Among the women with prenatal records available, the mean gestational age at initiation of prenatal care was 13.2 ± 6.5 weeks gestation. Women with prenatal care had a mean of 7.9 (95% CI 6.6, 9.4) prenatal visits. Of the 46 women who had prenatal care and the opportunity to attend a postpartum visit (i.e. did not die while pregnant), 20 (43.5%) attended a postpartum visit.

Among the 59 maternal deaths from self-harm, 16.9% (n=10) had a substance use disorder documented in the prenatal medical record or during hospitalization for delivery or death; of whom 6 were either currently in substance use disorder treatment or had a documented history of substance use disorder treatment. In 10 (16.9%) cases, there was no documentation of screening for substance use disorder in the prenatal medical record. A urine toxicology screen was performed at a prenatal visit for only 8 (13.6%) of the women.

Prior psychiatric diagnoses (Table 1) were documented in the clinical records of 54.2% (n=32) and prior suicide attempts in 10.2% (n=6). Of the 6 women with documentation of prior suicide attempts, five completed suicide and 1 died of an accidental overdose. Thirteen women (22.0%) did not have a known psychiatric or substance use disorder.

Depression was the most common documented psychiatric diagnosis (Table 1). While approximately half (n=27) of the self-harm cases were documented to be taking psycho-pharmacotherapy at conception, 48% of them discontinued the medications as a result of the pregnancy. Self-discontinuation of the medication(s) occurred in 9 cases, and discontinuation at the recommendation of a physician occurred in 4 cases. In the majority of women, psycho-pharmacotherapy consisted of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Other notable prescribed therapies included: sleep aids, mood stabilizers, and other classes of antidepressants. SSRIs were the drug class most commonly discontinued during pregnancy; 10 of the 13 women who discontinued medications stopped taking an SSRI. Four of the 13 women who were documented to have stopped the medications during pregnancy had psychiatric medications on toxicology testing at the time of autopsy.

Social stressors were commonly documented in the medical records of women who died of self-harm including: unemployment (n=38, 64.4%), being single, divorced or separated (n=24, 40.7%), history of domestic violence (n=11, 18.6%), unstable living situations such as homelessness (n=3, 5.1%), and current domestic violence (n=3, 5.1%). Based on the medical record or coroner report, the father of the child was noted to be involved in the majority (n=41, 69.5%) of cases. Despite documentation of social stress in the majority of women, engagement with a social worker was only found in 21 (35.6%) cases either during the course of prenatal care or at the time of delivery.

Adverse obstetrical events [preterm delivery, preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction, 3rd or 4th degree laceration, stillbirth, neonatal intensive care unit (ICU) admission, or maternal ICU admission] occurred in 16 (27.1%) cases. There was a preterm (<37 weeks gestation) delivery rate of 10.2% (n=6) among the cases; all of these neonates were admitted to the neonatal ICU.

The demographic characteristics of women with a maternal death are summarized along with the characteristics of all women with live births in Colorado over the same time period in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Maternal Deaths in Colorado from Suicide or Drug Overdose Compared to Women with Live Births from 2004-2012

| Characteristic | Maternal Deaths from Suicide or Overdose (N=59) | Women with Live Births Over Same Time Period (N=614,154) |

|---|---|---|

| Residence, n (%) | ||

| Urban | 47 (79.7) | 539,793 (87.9) |

| Rural | 9 (15.3) | 61,175 (10.0) |

| Frontier | 2 (3.4) | 13,169 (2.1) |

| Unknown | 1 (1.7) | 17 (0.0) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 44 (74.6) | 368,782 (60.0) |

| Hispanic | 10 (17.0) | 169,344 (27.6) |

| Other | 4 (6.8) | 57,801 (9.4) |

| Married at delivery, n (%) | 21 (39.6) | 456,931 (74.4) |

| Insurance status†, n (%) | ||

| Medicaid | 34 (57.6) | 142,870 (35.2) |

| Private Insurance | 12 (20.3) | 213,321 (52.5) |

| Self-Pay/Uninsured | 3 (5.1) | 19,425 (4.8) |

| Other/Unknown | 10 (17.0) | 30,404 (7.5) |

Insurance status was not collected until 2007 on Colorado birth certificates (n=406,020).

Discussion

Self-harm (accidental overdose and suicide) was the leading cause of maternal death in Colorado from 2004 to 2012, with a mortality ratio of 9.6 per 100,000 live births. Almost 90% of the deaths from self-harm occurred in the postpartum period. In the majority of cases, substance use and psychiatric disorders were present. However, in 22% of women with maternal deaths neither of these risk factors were present. Depression was the most common psychiatric diagnosis. Almost half of women on psychiatric medications in early pregnancy discontinued them during pregnancy or postpartum either on their own or at the recommendation of a care provider. Pharmaceutical opioids were the most common substance identified on toxicology screening at the time of autopsy.

Colorado's maternal death ratio from suicide (4.6 per 100,000 live births) is higher than that reported based on national pregnancy mortality surveillance (1.6-4.5 suicides per 100,000 live births)11, and data from the National Violent Death Reporting System (2.0 suicides per 100,000 live births).12 Colorado's higher suicide ratio may be the result of the comprehensive case identification approach employed by this study. Alternatively, our rates of suicide in pregnancy and postpartum may reflect the high rates of suicide in the general Colorado population. Suicide was the most common cause of death in Coloradans age 10-44 years, with a rate of 19.7 per 100,000 population in 2012.13

The lack of ongoing treatment for psychiatric disorders observed in our case study is consistent with a recently published study from the United Kingdom demonstrating that perinatal women were more likely to carry a diagnosis of depression yet were half as likely to receive any active treatment than non-perinatal women.14 These findings contrast with the accumulating body of evidence supporting the safety of antidepressants such as serotonin specific reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy.15,16

Maternal deaths were infrequent during pregnancy, consistent with existing literature.17,18 Less than 50% of women with maternal deaths from self-harm attended a postpartum visit; thus, targeting postpartum visits alone for depression screening and management will be inadequate to reach women at risk. Rather, each point of contact with women at risk for self-harm should be considered an opportunity for intervention including: pre-conception visits, antenatal care, hospitalization for delivery, and postpartum visits for both the mother and the neonate. During pregnancy and postpartum, women at risk for self-harm may encounter various types of providers including social workers, nurses, and physicians (psychiatrists, addiction specialists, obstetricians, adult primary care providers, pediatricians, and emergency medicine physicians). Resources for providers for screening and referring women at risk for self-harm are readily available from multiple organizations such as the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (https://www.nichd.nih.gov/ncmhep/MMHM/Pages/index.aspx), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (http://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/SMA14-4878/SMA14-4878.pdf), and the Council on Patient Safety in Women's Health (http://www.safehealthcareforeverywoman.org).

Successful interventions for prevention of maternal self-harm will likely require a multi-tiered approach, with interventions based at the individual patient and provider level, as well as broader changes at the health care delivery system and community level. We provide examples of potential interventions at each of these four levels in Table 3. Our group has integrated perinatal mental health screening, assessment and treatment into prenatal clinics, similar to a recently published study by Avalos et al.19 Universal screening will be necessary to identify the 22% of women in our series who did not have any identifiable risk factors for self-harm. To this end, we hope to establish virtual and electronic access to mental health resources for physicians in rural communities without local psychiatric services, so that providers can screen women for mental health disorders, and then promptly refer for further assessment and treatment. We also now include substance use and psychiatric experts on our Maternal Mortality Review Committee.

Table 3.

Possible Points of Intervention for Women at Risk for Self-Harm

| Tier of Intervention | Examples of Possible Interventions |

|---|---|

| Individual Patients | • Pharmacotherapy for psychiatric conditions • Patient education about available resources |

| Providers | • Provider education and access to available mental health and substance use disorder treatment resources • Judicious prescribing of opioids • Screening, identification and referral of women at risk |

| Healthcare Delivery System | • Multidisciplinary care teams with expertise in substance use and mental health disorders • Improved access to psychiatric care with urgent availability • Universal screening policies as part of care delivery • Integrated care systems with obstetricians, primary care and pediatrics |

| Community/State/National | • Hotlines for women to call when in crisis • Outreach through patient navigation or nursing home visitation programs • Public education to reduce stigma associated with mental health disorders • Surveillance and quality improvement reviews of maternal self-harm incidents |

Strengths of this study include 9 years of data from multiple sources that were reviewed by the Colorado Maternal Mortality Review Committee. Detailed chart abstraction allowed for ascertainment of data that are not available by collecting diagnostic codes alone. Limitations of this study include a possible underestimation of psychiatric diagnoses, treatments, and medications, as well as substance use treatment, since psychiatric records may not always have been available through the hospital or prenatal care providers. Further, we could not make comparisons to other women with live births in Colorado over the same time period for prevalence of risk factors given the limited demographic data available on birth certificates.

Our findings suggest that initiatives to increase community awareness, screening and referral to treatment for mental health and substance use disorders in pregnancy, along with recognition of the need for ongoing care beyond the early postpartum period, will be critical in reducing pregnancy-associated deaths from self-harm.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kirk Bol and Lauren Bardin at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment for their assistance with obtaining birth certificate data for all live births over the study period as well as for identification of the cases of maternal death.

Supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant number R24 HS022143-01, and National Institutes of Health/National Center for Research Resources Colorado CTSI grant number UL1 TR001082. Dr. Binswanger was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R34DA035952. Dr. Metz was supported by the National Institute on Child Health and Human Development under Award Number 2K12HD001271-16. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the National Institutes of Health. In addition, the Colorado Maternal Mortality Review Committee received funding from the Association of Maternal and Child Health Programs (AMCHP) and Merck for Mothers to assist with the expansion of the committee and to allow for further exploration of suicide as a cause of maternal death in Colorado to identify possible points of intervention.

Footnotes

Presented as a poster at the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine 36th Annual Meeting, Atlanta, GA, February 1-6, 2015.

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Main EK, Menard MK. Maternal mortality: time for national action. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;122(4):735–736. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182a7dc8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'Alton ME, Main EK, Menard MK, Levy BS. The National Partnership for Maternal Safety. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;123(5):973–977. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Council on Patient Safety in Women's Healthcare [May 10, 2016];Maternal mental health: perinatal depression and anxiety. http://www.safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/secure/maternal-mental-health.php.

- 4.Kozhimannil KB, Adams AS, Soumerai SB, Busch AB, Huskamp HA. New Jersey's efforts to improve postpartum depression care did not change treatment patterns for women on medicaid. Health Aff. (Millwood) 2011;30(2):293–301. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flanagan T, Avalos LA. Perinatal Obstetric Office Depression Screening and Treatment: Implementation in a Health Care System. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016;127(5):911–915. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [April 29, 2016];Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. 2016 http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html.

- 7.Rockett IR, Smith GS, Caine ED, et al. Confronting death from drug self-intoxication (DDSI): prevention through a better definition. American journal of public health. 2014;104(12):e49–55. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanistreet D, Taylor S, Jeffrey V, Gabbay M. Accident or suicide? Predictors of Coroners' decisions in suicide and accident verdicts. Med. Sci. Law. 2001;41(2):111–115. doi: 10.1177/002580240104100205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berg C DI, Atrash H, Zane S, Bartlett L. Strategies to reduce pregnancy-related deaths: from identification and review to action. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace ME, Hoyert D, Williams S, et al. Pregnancy-associated homicide and suicide in 37 US states with enhanced pregnancy surveillance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.03.040. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palladino CL, Singh V, Campbell J, Flynn H, Gold KJ. Homicide and suicide during the perinatal period: findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;118(5):1056–1063. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823294da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment [April 29, 2016];Suicide in Colorado (2008-2012) 2014 https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/files/Suicide-in-Colorado-2008-2012.pdf.

- 14.Khalifeh H, Hunt IM, Appleby L, Howard LM. Suicide in perinatal and non-perinatal women in contact with psychiatric services: 15 year findings from a UK national inquiry. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(3):233–242. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huybrechts KF, Hernandez-Diaz S, Avorn J. Antidepressant use in pregnancy and the risk of cardiac defects. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(12):1168–1169. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1409203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huybrechts KF, Bateman BT, Palmsten K, et al. Antidepressant use late in pregnancy and risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Jama. 2015;313(21):2142–2151. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.5605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marzuk PM, Tardiff K, Leon AC, et al. Lower risk of suicide during pregnancy. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1997;154(1):122–123. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Appleby L. Suicide during pregnancy and in the first postnatal year. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 1991;302(6769):137–140. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6769.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Avalos LA, Raine-Bennett T, Chen H, et al. Improved perinatal depression screening, treatment and outcomes with a universal obstetric program. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(5):917–25. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]