Abstract

Background

Altered pulmonary function is present early in the course of cystic fibrosis (CF), independent of documented infections or onset of pulmonary symptoms. New initiatives in clinical care are focusing on detection and characterization of pre-clinical disease. Thus, animal models are needed which recapitulate the pulmonary phenotype characteristic of early stage CF.

Methods

We investigated young CF mice to determine if they exhibit pulmonary pathophysiology consistent with the early CF lung phenotype. Lung histology and pulmonary mechanics were examined in 12–16 week old congenic C57bl/6 F508del and R117H CF mice using a forced oscillation technique (flexiVent).

Results

There were no significant differences in the resistance of the large airways. However, in both CF mouse models, prominent differences in the mechanical properties of the peripheral lung compartment were identified including decreased static lung compliance, increased elastance and increased tissue damping. CF mice also had distal airspace enlargement with significantly increased mean linear intercept distances.

Conclusions

An impaired ability to stretch and expand the peripheral lung compartment, as well as increased distances between gas exchange surfaces, were present in young CF mice carrying two independent Cftr mutations. This altered pulmonary histopathophysiology in the peripheral lung compartment, which develops in the absence of infection, is similar to the early lung phenotype of CF patients.

Keywords: Cystic fibrosis, lung mechanics, mouse models

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene. The CF pulmonary phenotype worsens over time; progressing from early, pre-symptomatic pathophysiologic changes in the lung and airways to overt disease with mucus obstruction and bronchiectasis. Progressive lung disease characterized by recurrent infections is the major cause of morbidity and mortality. However, growing evidence suggests that the CF pulmonary phenotype develops prior to, and partially independent of, the recurrent cycle of infection, inflammation and obstruction (1–5). Early manifestations of the CF pulmonary phenotype include increased airway resistance, evidence of gas trapping and diminished expiratory flow rates and volumes. These abnormalities have been reported in young patients with mild CF (6) and in clinically stable individuals without detectable infection (7–14). Using the single frequency forced oscillation technique, decreases in reactance (Xrs) and increases in resistance (Rrs) of the respiratory system in CF patients has been reported, although the magnitude of these differences was not consistent across studies (7, 15–17), likely due to variability of clinical status in these cohorts. Taken together, these findings indicate that a phenotype of altered pulmonary function is present early in the course of CF, independent of documented infections, or onset of pulmonary symptoms.

The advent of newborn screening has enabled clinical studies of lung function parameters in pre-symptomatic patients with CF, and has extended the time between diagnosis and onset of overt symptoms. This silent period provides a window of opportunity where therapeutic interventions may be most effective (18, 19). Thus, a recent focus has been on the early detection (18, 20–24) and treatment (25, 26) of pre-symptomatic CF patients. However, these efforts are challenged by the fact that there is an incomplete understanding of the underlying pathobiology of lung function in early CF. As clinical strategies shift from treatment of symptoms to prevention of progressive lung disease, animal models are needed which manifest the pulmonary pathology characteristic of the early CF phenotype. In the present work we demonstrate that two different mouse models of human CFTR mutations (F508del and R117H) exhibit significant histological and lung mechanical differences, which are localized to the peripheral lung compartment. CF mouse lungs exhibited a greater mean free distance between gas exchange surfaces and had an impaired ability to stretch and expand. These alterations in respiratory mechanics and lung structure were identified in the absence of infection, detectable airway mucus or inflammatory cell infiltration, and are similar to the early pulmonary phenotype described in CF patients (20, 27–29).

Materials and Methods

Mice

Two congenic CF mouse models were utilized: homozygous F508del Cftr mutation (Cftrtm1kth) (30), and homozygous R117H mutation (31). These mutations have been backcrossed >10 generations to the C57Bl/6J strain to make the strains congenic. Non-CF mice were wildtype (WT) littermates of the CF mice. All CF and non-CF mice used in the study were young adults (8–16 weeks old). Mice were allowed unrestricted access to chow (Harlan Teklad 7960; Harlan Teklad Global Diets, Madison, WI) and sterile water with an osmotic laxative, Colyte (Schwarz Pharma, Milwaukee, WI), and were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle at a mean ambient temperature of 22°C. WT mice (n=7; 4 males and 3 females) weighed 25.6±3.6g. F508del CF mice (n=6, 4 males and 2 females) weighed 22.4±2.7g (p<0.04 compared to WT mice), and R117H CF mice (n=6, 3 males and 3 females) weighed 19.1±2.4g (p<0.01 compared to WT mice). While the body weights of both CF groups were less than WT, there were no statistically significant differences in lung weight, height or width (Table 1).

Table 1.

| Body weight (g) | Lung weight (g) | Lung height (mm) | Lung width (mm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 25.6 ± 3.6 | 0.16 ± 0.04 | 10.6 ± 0.7 | 5.8 ± 0.5 |

|

|

||||

| F508del | 22.4 ± 2.7* | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 10.5 ± 0.7 | 5.7 ± 0.6 |

|

|

||||

| R117H | 19.1 ± 2.4* | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 10.2 ± 0.3 | 5.3 ± 0.5 |

|

|

||||

p<0.05 compared to WT

Screening for infectious organisms and specific pathogen testing

Sentinel mice from the colony were screened on a monthly basis via culture of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. During the course of this study, no active infections were detected in any of the sentinel animals housed alongside the experimental animals. In addition, all the experimental animals were tested using serum ELISA for Bordetella hinzii, which is the only known pathogen to be identified in this mouse colony. All experimental mice tested negative for any current or previous B. hinzii infection.

Respiratory mechanics

Forced oscillation measurements were obtained in intact, intubated, anesthetized mice. Following induction of anesthesia via intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (150 mg/kg) and xylazine (15 mg/kg), tracheotomy and cannulation (Becton Dickinson Angiocath, 20GA, trimmed to 20mm length) were performed. Animals were mechanically ventilated using a computer-controlled mechanical ventilator (flexiVent system, SCIREQ) at a rate of 150 breaths/minute with tidal volumes of 10mL/kg and positive end-expiratory pressure of 3 cmH2O. Lung mechanics measurements were made using automated maneuvers and analysis algorithms as described previously (32). Briefly, inspiratory capacity was measured by slow lung inflations to 30 cmH2O over 3s. Data obtained from single-frequency forced oscillation maneuvers were used to calculate overall respiratory system resistance (Rrs), compliance (Crs) and elastance (Ers), using operating software and assuming a single compartment model of the respiratory system. Respiratory input impedance was calculated from automated measurements made during a broadband low-frequency forced oscillation maneuver with a mixed frequency forcing function comprised of multiple prime frequencies ranging from 0.25 to 20Hz. Operating software fit a constant phase model to the respiratory input impedance to determine Newtonian resistance (Rn), tissue damping (G) and tissue elastance (H). Parameters from individual data sets were included in the final analysis, provided that the coefficient of determination assessing the fit of the model to the experimental data was ≥ 0.95. Pressure-volume curves were produced by stepped increases and subsequent decreases in airway pressure. At each step, a pause of 1s was conducted during which the plateau pressure and change in lung volume was measured. Static lung compliance (Cst) was calculated from the slope of each curve. The area (Hysteresis) of the pressure-volume curve and a shape parameter (K) describing the deflation limb of the pressure-volume loop were also calculated.

Histology

Separate groups of mice (WT (n=6); F508del (n=6); R117H (n=5)) were used for histologic determinations. Following CO2 euthanasia, a tracheotomy was performed and the lungs were pressure inflated to 30cmHg with 10% buffered formalin for 30 minutes. Lungs were then removed and fixed in 10% buffered formalin for ten days. Fixed specimens were embedded in paraffin, sectioned in 150μm increments at a thickness of 5μm, and mounted on glass slides. For assessment of airway luminal diameter, presence of inflammatory cells and distal airspace structure, one slide from each specimen was stained with hematoxylin/eosin (H&E). For visualization of mucosubstances, one slide from each specimen was stained with Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS). Slides were analyzed with bright field microscopy at 10× and 20× magnification. Airway luminal diameter was measured using a 1mm stage micrometer. A Mean Linear Intercept (MLI, Lm) calculation was used to quantitatively assess distal airspace enlargement. An indirect method was utilized, in which the software generated a test-line of known length across multiple 20× fields of view, to represent ~5% of the total lung area. The Lm was then determined by calculating the ratio of line endpoints within parenchyma, including airspaces and ductal spaces [P(A) + P(duct)], to points intersecting the septum [I(A)] across the known-length test line (d) (excluding nonparenchyma structures) (33), as indicated by the following formula (34):

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used for summarizing pulmonary function measurements, airway luminal diameters and MLI distances. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze the differences between group means using the statistical software package Stata 13.0. When significant differences were detected, a pairwise comparison of the means of each combination of groups was conducted assuming equal variances. We accounted for multiple comparisons using the Sidak procedure. Corrected p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Overall mechanics of the respiratory system

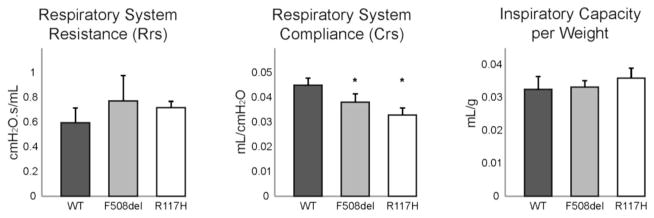

Lung mechanics were initially assessed using a single-frequency forced oscillation approach, which assumes a linear, first-order single compartment model of the respiratory system (Fig 1). Respiratory system compliance (Crs) was significantly reduced in both F508del (0.038±0.003 mL/cmH2O; p=0.003) and R117H (0.033±0.003 mL/cmH2O; p<0.001) compared to wild type (WT) controls (0.045±0.003 mL/cmH2O). Analogous increases in elastance (Ers) of the respiratory system were also identified in both F508del (p=0.010) and R117H (p<0.001). Resistance of the overall respiratory system tended to be higher (p=0.09) in both groups of CF mice when compared to WT mice (Fig 1). Inspiratory capacity normalized to body weight (Fig 1) was not different between CF and WT mice (p=0.15). These data quantify a CF lung phenotype, but were unable to localize the anatomic source of these differences.

Figure 1. Overall mechanics of the respiratory system are altered in CF mice.

Single compartment analysis of respiratory system mechanics using flexiVent forced oscillation technique in wild type mice (black bars, n=7), F508del (grey bars, n=6) and R117H (white bars, n=6) cystic fibrosis mice. Compliance of the respiratory system was significantly decreased in both CF mice as compared to WT control mice (*p<0.05). Overall resistance of the respiratory system tended to be greater in CF mice (p=0.09). Inspiratory capacity normalized to body weight was not different between groups.

Distinguishing central from peripheral lung compartments

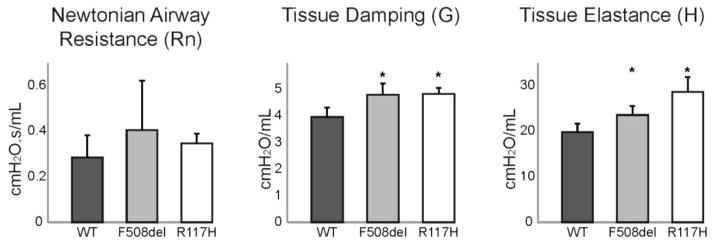

To further evaluate the observed changes in lung mechanics, broadband forced oscillations were used to discriminate central and peripheral lung mechanics (Fig 2). Using this constant phase model, Newtonian airway resistance (Rn) was not different between CF and WT mice (p=0.31). However, tissue damping (G) was increased in both F508del (4.80±0.43 cmH2O/mL; p=0.001) and R117H (4.84±0.22 cmH2O/mL; p=0.001) mice compared to WT (3.97±0.34 cmH2O/mL). Tissue elastance (H) was also increased in both F508del (23.6±1.9 cmH2O/mL; p=0.040) and R117H (28.6±3.3 cmH2O/mL; p<0.001) compared to WT (19.8±1.9 cmH2O/mL). Thus, the changes in respiratory system mechanics were not due to increases in resistance of the large conducting airways. Rather, the observed differences in the mechanical properties of the peripheral tissue compartment of CF mice reflected alterations in the small airways, lung parenchyma, or both.

Figure 2. Significant differences in the mechanical properties of the CF lung are localized to the peripheral tissue compartment and not the central airways.

Constant phase analysis was used to discriminate central and peripheral lung mechanics in wild type mice (black bars, n=7), F508del (grey bars, n=6) and R117H (white bars, n=6) cystic fibrosis mice. Newtonian airway resistance (central compartment) was similar between groups. Tissue damping (G) and tissue elastance (H) of the peripheral lung compartment were both significantly increased in both CF mice (*p<0.05).

Pressure-volume loops and static lung mechanics

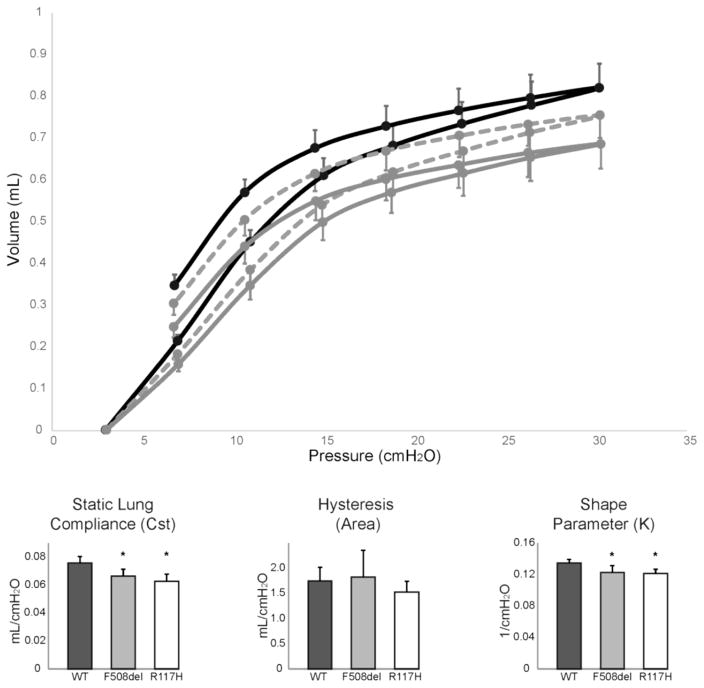

To specifically quantify the contribution of lung parenchyma to the observed CF pulmonary phenotype, quasi-static mechanical properties of the respiratory system were measured. Pressure-volume loops constructed from average data from WT and CF mice (Fig 3, top panel) indicate the intrinsic stiffness of the lung and chest wall is increased (lower static compliance under closed-chest conditions) in CF mice. Compared to WT mice (0.076±0.005 mL/cmH2O), static compliance (Cst) was significantly reduced in both F508del (0.066±0.005 mL/cmH2O; p=0.009) and R117H (0.063±0.005 mL/cmH2O; p=0.001) CF mice (Fig 3). The overall area of the pressure-volume loops was not significantly different (p=0.35; Fig 3), indicating that hysteresis was unchanged. However, differences in the shape of the pressure-volume loop, as quantified by a shape parameter (K, Fig 3), was significantly different in both F508del (0.123±0.008 1/cmH2O; p=0.011) and R117H (0.122±0.005 1/cmH2O; p=0.005) mice compared to WT (0.135±0.005 1/cmH2O).

Figure 3. Pressure-volume loops identify differences in lung mechanics.

Pressure-volume loops (top panel) generated by stepped inflation and deflation maneuvers in wild type mice (solid black line, n=7), F508del (dashed grey line, n=6) and R117H (solid grey line, n=6) cystic fibrosis mice. Static lung compliance (Cst) was significantly reduced in CF (grey and white bars) as compared to WT mice (black bars). The area between the inflation and deflation limbs of the pressure-volume loop was similar among all groups. Significant differences were present in the shape of the deflation limb of the pressure-volume loop as quantified by the shape parameter (K). *p<0.05

Lung histology

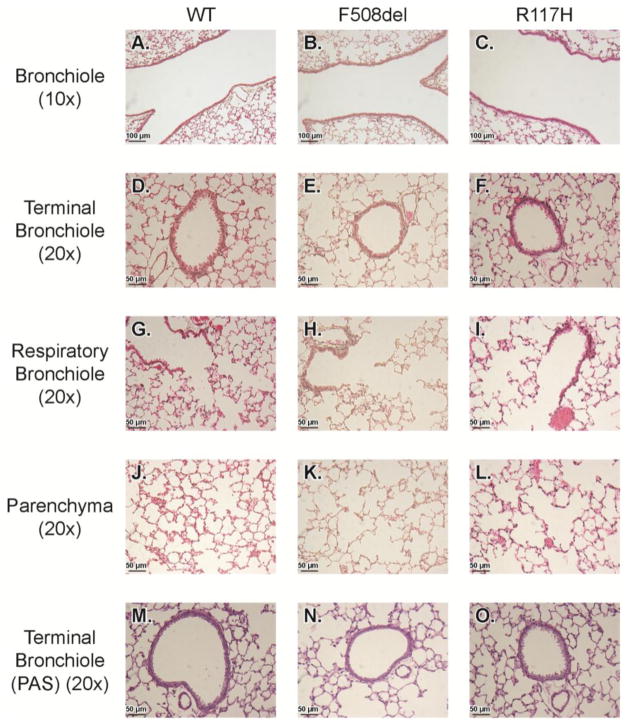

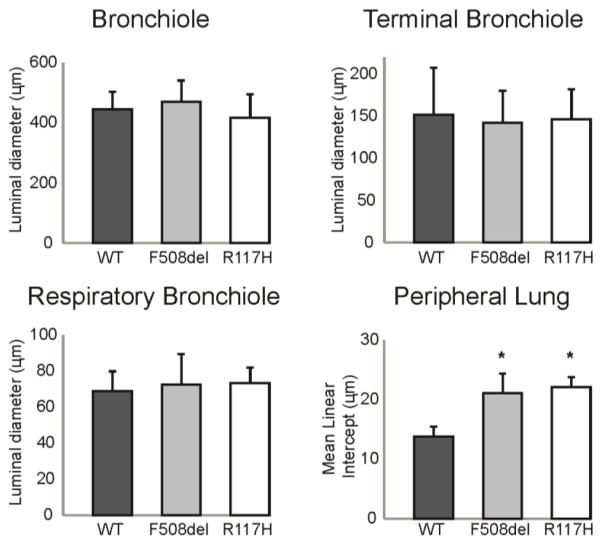

To further investigate the anatomical source of the changes indicated by the pulmonary mechanics measurements, a histological analysis of the large conducting airways (bronchioles and terminal bronchioles), small airways (respiratory bronchioles), and distal airspaces was performed (Fig 4). There were no differences in luminal diameters of the bronchioles (p=0.50), the terminal bronchioles (p=0.93) or the respiratory bronchioles (p=0.84) (Fig 5). Mucus (PAS stain) was not present in the airway lumens, and there was no inflammatory infiltration within the airway walls (Fig 4). However, there were structural changes in CF lung parenchyma. Both CF mouse models displayed a visible increase in airspace diameter (Fig 4) that was quantified using a mean linear intercept (MLI) calculation of distal airspace enlargement. MLI was significantly increased in F508del (21.1±3.3 μm; p<0.005), and R117H (22.1± 1.7 μm; p<0.005) compared to WT (13.8±1.7 μm) (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Histologic analysis of the airways and lung parenchyma.

Representative micrographs of WT, F508del, and R117H mice are displayed. Bronchioles were visualized at 10× (A–C), and all others were visualized at 20× (D–O). Slides were stained with H&E (A–L), and the terminal bronchioles were also stained with PAS to verify the absence or presence of any mucoid substance in the airway lumen (M–O).

Figure 5. Quantitative assessment of the airway luminal diameter and peripheral lung airspace structure.

Measurements of the luminal diameter of the bronchioles, terminal bronchioles, and respiratory bronchioles showed no difference in CF (grey bars, n=6; white bars, n=5) and WT (black bars, n=6) lung. The mean linear intercept was significantly increased in CF peripheral lung compared to WT. *p<0.05

In summary, compared to WT controls, there were overall differences in the mechanical properties of the respiratory system in two independent CF mouse models. These differences were localized to the peripheral lung compartment, which is comprised of the small airways and the lung parenchyma. Histological analyses confirmed enlargement of the distal airspaces consistent with the peripheral lung compartment as the anatomical source of the changes in pulmonary mechanics.

Discussion

The objective of the present study was to evaluate two independent CF mouse models to determine the extent to which they recapitulate the early CF lung phenotype in humans. Resistance of the large airways was unchanged in CF mice, however prominent differences in the mechanical properties of the peripheral lung compartment were identified. Histological analysis revealed distal airspace enlargement without significant differences in the luminal diameter of any of the bronchioles. These differences indicate the initial development of pathologic manifestations in the peripheral compartment, and were detected in the absence of mucus, overt inflammation, or infection in CF mice. Distal airway alterations such as those described here in both CF mouse models are consistent with the initial stages of the preclinical pulmonary phenotype in CF patients (20, 27–29). In particular, early in the course of CF, patients have abnormal increases in airway resistance and associated gas trapping (35, 36), which often occurs independent of lung infection or environmental factors (9, 10, 37). Using the forced oscillation technique, alterations in pulmonary mechanics have been observed as an early pulmonary change in CF patients (16). Airway resistance is also increased in young children with CF compared to healthy controls (12, 37). These differences were independent of infection and typically present early in the course of CF. Although infection will worsen these changes over time (1, 29), this baseline phenotype exists prior to the development of symptoms, as significant increases in the resistance of the small airways and evidence of gas trapping may occur even in patients with spirometry within normal limits (1, 4, 5).

Our study identified CF-specific changes in respiratory mechanics in F508del and R117H CF mice. Initial protocols employed dynamic measurements which model the respiratory system as a uniform single compartment. During single-frequency forced oscillations, CF mice had decreased dynamic compliance and increased dynamic elastance of the whole respiratory system, including the airways, lung parenchyma and chest wall. These data indicate that with the movement of gas during breathing, extra work will be required to exchange a volume of air to expand and deflate the lungs of CF mice. While these findings clearly identified differences in pulmonary mechanics between CF and non-CF mice, the anatomical source of these alterations cannot be determined using the single compartment approach.

A broadband forced oscillation technique was utilized to determine whether the observed differences in respiratory mechanics were due to the central (large airways) and/or peripheral (small airways and distal lung structures) lung compartments. The central airways, which are characterized by Newtonian airflow, had similar resistance measurements between CF and non-CF mice. Thus, the large airways are not the source of the decrease in dynamic lung compliance. In contrast, there were significant differences in peripheral lung mechanics, which could reflect differences in either the peripheral airways and/or peripheral tissues (38). In particular, CF mice had increased tissue damping and increased tissue elastance of the peripheral lung compartment. This indicates that in the lungs of CF mice, more energy is lost to frictional or other resistive forces and that more work will be required to expand the lungs.

To determine if the observed differences in CF peripheral lung mechanics were reflective of changes in the lung parenchyma, static measurements of lung mechanics were made. Although inspiratory capacity was similar between CF and non-CF mice, static lung compliance (Cst) was different between the groups. Static measures of compliance are not influenced by properties of the large airways, but rather reflect the peripheral lung tissue’s intrinsic tendency to inflate or deflate under a given pressure change. Thus, this finding identifies a difference in the CF lung parenchyma’s ability to stretch and expand. To further quantify the mechanical behavior of CF lungs under static conditions, quasi-static pressure-volume loops were measured. The area between the inflation and deflation limbs (hysteresis) was similar between the groups. However, significant differences in the shape of the deflation limb (K) were identified. Specifically, the slope of the pressure-volume curve during stepwise deflation was less in CF mice, indicating a smaller volume of air was expelled from CF lungs in response to a given decrease in pressure. Therefore, under normal conditions, an extended period of exhalation would be required for a given volume of air to exit CF lungs. These data confirm that CF-specific changes in the peripheral lung compartment contribute to the differences in the mechanical properties of the respiratory system between CF and non-CF mice.

Taken together, these data indicate that homozygous F508del and R117H CF mice have decreased dynamic compliance of their overall respiratory system. This is not due to changes in the resistance of the large airways. Rather, our findings indicate increased impedance of the distal airways and airspaces in CF mice, likely due to CF-specific changes in the small airways and/or alveolar spaces. The development of pathologic changes in the peripheral lung compartment might be associated with differences in lung architecture. To further evaluate this possibility, histological analysis of the CF mouse lung was used to confirm the anatomical source of the changes in pulmonary mechanics. Luminal diameter of the conducting airways (bronchioles and terminal bronchioles) and small airways (respiratory bronchioles) was measured, and the CF mice were not different from the non-CF mice. This was consistent with the pulmonary mechanics data that indicated no difference in the resistance of the central airways of the CF mouse. Measurements of anatomical structure of the distal airspaces identified increased mean linear intercept distances suggestive of a greater mean free distance between gas exchange surfaces within the three-dimensional acinar surface complex of the peripheral lung compartment. Increased mean linear intercept distances have been reported in children with CF, and were interpreted as being clinically indicative of over-inflation or gas trapping (39). In summary, CF mice exhibit physiologic and histologic evidence of pulmonary pathology consistent with features of the early CF pulmonary phenotype in humans (1, 4, 6, 7, 16, 37, 39).

The pulmonary mechanics phenotype described here was apparent in both CF mouse models, which were age-matched to non-CF control mice. As a result, the CF mice weighed less than the non-CF mice used in this study. While body weight is not a major contributor to lung function measurements, lung size is an important variable. Lung size and weight were measured and found to be similar in all 3 groups (Table 1), indicating that the differences in lung function measurements were not a direct result of differences in body weight. We elected not to weight-match the CF and non-CF mice, as this would have required using juvenile WT mice (~4 weeks of age) and would have introduced other confounding variables.

Respiratory mechanics have been previously evaluated in alternative mouse models of loss of Cftr (40–43). The findings of the present study are consistent with the previous reports, but extend the characterization of the pulmonary phenotype in CF mice in several important ways. Prior studies have suggested a change in lung architecture, but without a quantitative assessment of these differences (40, 43). Here, we used a mean linear intercept calculation to provide quantitative assessment of this phenotype in congenic C57Bl/6 F508del and R117H CF mice. The first report of altered pulmonary mechanics in CF mice utilized older F508del mice with varied genetic backgrounds (40). Subsequent studies detected increased resistance and elastance of the lungs of F508del CF mice (congenic on the FVB/N background), both at baseline and following methacholine challenge (42). These mice were of a similar age to those in the present study, however specific characterization of the contribution of central and peripheral lung compartments was not reported (42). Cohen, et al., used a forced oscillation technique to more completely evaluate pulmonary mechanics in CF mice, and reported findings similar to those described here including decreased compliance, increased tissue damping (G) and increased elastance (H) (41). However, these investigators used an alternative CF mouse model (null mutation) that was not congenic. Nevertheless, the fact that altered pulmonary mechanics described in the present study were also detected in alternative CF mouse models supports the conclusion that loss of Cftr results in changes in pulmonary mechanics. The present study extends that work by using young congenic C57BL/6 mice homozygous for two of the most common human CFTR mutations (F508del and R117H), and providing a characterization of both the pulmonary mechanics phenotype and alterations in lung architecture.

A limitation of the CF mouse as a model of the human CF pulmonary phenotype is that it does not naturally progress to more severe disease pathology, including bronchiectasis and mucus plugging of the conducting airways, which are among the most prevalent changes in patients with symptomatic CF (5). However, the CF pulmonary phenotype develops over time, and pathophysiologic changes in the lung and airways are present even in pre-symptomatic patients. The two described CF mouse models exhibit manifestations which are consistent with the early stage pulmonary phenotype present in pre-symptomatic CF patients. They offer the scientific community the opportunity to investigate the underlying effects of absent CFTR on lung physiology and mechanics in the absence of infection.

While the CF mouse is a useful model of the initial pulmonary phenotype, other CF animal models have been developed and used successfully to study the many manifestations of CF disease. For example, mice with airway specific overexpression of the epithelial Na(+) channel (ENaC) provide an alternative model to study mucus obstruction and chronic airway inflammation (44). Pig and ferret models, which have altered mucocilliary transport and develop spontaneous lung infections, have been developed to study the onset and progression of CF lung disease (45–47). However, the pulmonary phenotype in young CF mice identified and described here developed in the absence of detectable mucus obstruction and lung infection. This raises the possibility that these changes are initially attributable to the absence of functional Cftr. The development of infection in CF certainly hastens the progression of lung and airways disease (1, 29). However, our findings suggest that ongoing small airways disease and/or peripheral parenchymal changes may develop independently of infection or mucus plugging. Identifying the pathways responsible may lead to the identification of novel therapeutic targets or the development of disease modifying agents. Furthermore, there is a growing recognition that small airways disease, similar to that described here in the CF mouse, is present long before the overt manifestation of respiratory symptoms. Effective therapeutic agents for use during this period of silent progression of lung disease would be a major advance. The CF mouse offers the ability to begin the development and testing of such agents.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the Case Western Reserve University CF animal core for their work maintaining the mouse colony, and John Dunn for his assistance with figure preparation. In addition, we would like to thank Dr. Patricia Conrad, Director of the Light Microscopy Imaging Facility at Case Western Reserve University for her help with slide imaging. The Imaging Facility was made available through the Office of Research Infrastructure (NIH-ORIP Shared Instrumentation Grant S10RR031845).

Grant Support: This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RR-032425 Hodges and Drumm; CFF grants DRUMM15R0 and DRUMM15R1), a grant from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (R447-CR11 Drumm), and Award I01BX000873 from the Biomedical Laboratory Research & Development Service of the VA Office of Research and Development (Jacono).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kozlowska WJ, Bush A, Wade A, Aurora P, Carr SB, Castle RA, Hoo AF, Lum S, Price J, Ranganathan S, Saunders C, Stanojevic S, Stroobant J, Wallis C, Stocks J London Cystic Fibrosis C. Lung function from infancy to the preschool years after clinical diagnosis of cystic fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2008;178:42–49. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200710-1599OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linnane BM, Hall GL, Nolan G, Brennan S, Stick SM, Sly PD, Robertson CF, Robinson PJ, Franklin PJ, Turner SW, Ranganathan SC, Arest CF. Lung function in infants with cystic fibrosis diagnosed by newborn screening. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2008;178:1238–1244. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200804-551OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan TZ, Wagener JS, Bost T, Martinez J, Accurso FJ, Riches DW. Early pulmonary inflammation in infants with cystic fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1995;151:1075–1082. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/151.4.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoo AF, Thia LP, Nguyen TT, Bush A, Chudleigh J, Lum S, Ahmed D, Balfour Lynn I, Carr SB, Chavasse RJ, Costeloe KL, Price J, Shankar A, Wallis C, Wyatt HA, Wade A, Stocks J London Cystic Fibrosis C. Lung function is abnormal in 3-month-old infants with cystic fibrosis diagnosed by newborn screening. Thorax. 2012;67:874–881. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-201747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramsey BW, Banks-Schlegel S, Accurso FJ, Boucher RC, Cutting GR, Engelhardt JF, Guggino WB, Karp CL, Knowles MR, Kolls JK, LiPuma JJ, Lynch S, McCray PB, Jr, Rubenstein RC, Singh PK, Sorscher E, Welsh M. Future directions in early cystic fibrosis lung disease research: An nhlbi workshop report. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2012;185:887–892. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2068WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonnel AS, Song SM, Kesavarju K, Newaskar M, Paxton CJ, Bloch DA, Moss RB, Robinson TE. Quantitative air-trapping analysis in children with mild cystic fibrosis lung disease. Pediatric pulmonology. 2004;38:396–405. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brennan S, Hall GL, Horak F, Moeller A, Pitrez PM, Franzmann A, Turner S, de Klerk N, Franklin P, Winfield KR, Balding E, Stick SM, Sly PD. Correlation of forced oscillation technique in preschool children with cystic fibrosis with pulmonary inflammation. Thorax. 2005;60:159–163. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.026419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ren CL, Rosenfeld M, Mayer OH, Davis SD, Kloster M, Castile RG, Hiatt PW, Hart M, Johnson R, Jones P, Brumback LC, Kerby GS. Analysis of the associations between lung function and clinical features in preschool children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatric pulmonology. 2012;47:574–581. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marostica PJ, Weist AD, Eigen H, Angelicchio C, Christoph K, Savage J, Grant D, Tepper RS. Spirometry in 3- to 6-year-old children with cystic fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2002;166:67–71. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200111-056OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vilozni D, Bentur L, Efrati O, Minuskin T, Barak A, Szeinberg A, Blau H, Picard E, Kerem E, Yahav Y, Augarten A. Spirometry in early childhood in cystic fibrosis patients. Chest. 2007;131:356–361. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castile RG, Iram D, McCoy KS. Gas trapping in normal infants and in infants with cystic fibrosis. Pediatric pulmonology. 2004;37:461–469. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beydon N, Amsallem F, Bellet M, Boule M, Chaussain M, Denjean A, Matran R, Pin I, Alberti C, Gaultier C. Pulmonary function tests in preschool children with cystic fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2002;166:1099–1104. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200205-421OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen TT, Thia LP, Hoo AF, Bush A, Aurora P, Wade A, Chudleigh J, Lum S, Stocks J London Cystic Fibrosis C. Evolution of lung function during the first year of life in newborn screened cystic fibrosis infants. Thorax. 2014;69:910–917. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerby GS, Rosenfeld M, Ren CL, Mayer OH, Brumback L, Castile R, Hart MA, Hiatt P, Kloster M, Johnson R, Jones P, Davis SD. Lung function distinguishes preschool children with cf from healthy controls in a multi-center setting. Pediatric pulmonology. 2012;47:597–605. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lima AN, Faria AC, Lopes AJ, Jansen JM, Melo PL. Forced oscillations and respiratory system modeling in adults with cystic fibrosis. Biomedical engineering online. 2015;14:11. doi: 10.1186/s12938-015-0007-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gangell CL, Horak F, Jr, Patterson HJ, Sly PD, Stick SM, Hall GL. Respiratory impedance in children with cystic fibrosis using forced oscillations in clinic. The European respiratory journal. 2007;30:892–897. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00003407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nielsen KG, Pressler T, Klug B, Koch C, Bisgaard H. Serial lung function and responsiveness in cystic fibrosis during early childhood. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2004;169:1209–1216. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200303-347OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheikh SI, Long FR, Flucke R, Ryan-Wenger NA, Hayes D, Jr, McCoy KS. Changes in pulmonary function and controlled ventilation-high resolution ct of chest after antibiotic therapy in infants and young children with cystic fibrosis. Lung. 2015;193:421–428. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9706-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramsey KA, Ranganathan S, Park J, Skoric B, Adams AM, Simpson SJ, Robins-Browne RM, Franklin PJ, de Klerk NH, Sly PD, Stick SM, Hall GL, Arest CF. Early respiratory infection is associated with reduced spirometry in children with cystic fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2014;190:1111–1116. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201407-1277OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall GL, Logie KM, Parsons F, Schulzke SM, Nolan G, Murray C, Ranganathan S, Robinson P, Sly PD, Stick SM, Arest CF, Berry L, Garratt L, Massie J, Mott L, Poreddy S, Simpson S. Air trapping on chest ct is associated with worse ventilation distribution in infants with cystic fibrosis diagnosed following newborn screening. PloS one. 2011;6:e23932. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ribeiro MA, Silva MT, Ribeiro JD, Moreira MM, Almeida CC, Almeida-Junior AA, Ribeiro AF, Pereira MC, Hessel G, Paschoal IA. Volumetric capnography as a tool to detect early peripheric lung obstruction in cystic fibrosis patients. Jornal de pediatria. 2012;88:509–517. doi: 10.2223/JPED.2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogers GB, Hoffman LR, Johnson MW, Mayer-Hamblett N, Schwarze J, Carroll MP, Bruce KD. Using bacterial biomarkers to identify early indicators of cystic fibrosis pulmonary exacerbation onset. Expert review of molecular diagnostics. 2011;11:197–206. doi: 10.1586/erm.10.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linnane B, Robinson P, Ranganathan S, Stick S, Murray C. Role of high-resolution computed tomography in the detection of early cystic fibrosis lung disease. Paediatric respiratory reviews. 2008;9:168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2008.05.009. quiz 174–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ranganathan S, Linnane B, Nolan G, Gangell C, Hall G. Early detection of lung disease in children with cystic fibrosis using lung function. Paediatric respiratory reviews. 2008;9:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Douglas TA, Brennan S, Gard S, Berry L, Gangell C, Stick SM, Clements BS, Sly PD. Acquisition and eradication of p. Aeruginosa in young children with cystic fibrosis. The European respiratory journal. 2009;33:305–311. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00043108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Accurso FJ, Moss RB, Wilmott RW, Anbar RD, Schaberg AE, Durham TA, Ramsey BW Group T-IS. Denufosol tetrasodium in patients with cystic fibrosis and normal to mildly impaired lung function. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2011;183:627–634. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201008-1267OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sly PD, Brennan S, Gangell C, de Klerk N, Murray C, Mott L, Stick SM, Robinson PJ, Robertson CF, Ranganathan SC Australian Respiratory Early Surveillance Team for Cystic F. Lung disease at diagnosis in infants with cystic fibrosis detected by newborn screening. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2009;180:146–152. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200901-0069OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stick SM, Brennan S, Murray C, Douglas T, von Ungern-Sternberg BS, Garratt LW, Gangell CL, De Klerk N, Linnane B, Ranganathan S, Robinson P, Robertson C, Sly PD Australian Respiratory Early Surveillance Team for Cystic F. Bronchiectasis in infants and preschool children diagnosed with cystic fibrosis after newborn screening. The Journal of pediatrics. 2009;155:623–628. e621. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pillarisetti N, Williamson E, Linnane B, Skoric B, Robertson CF, Robinson P, Massie J, Hall GL, Sly P, Stick S, Ranganathan S Australian Respiratory Early Surveillance Team for Cystic F. Infection, inflammation, and lung function decline in infants with cystic fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2011;184:75–81. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1892OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeiher BG, Eichwald E, Zabner J, Smith JJ, Puga AP, McCray PB, Jr, Capecchi MR, Welsh MJ, Thomas KR. A mouse model for the delta f508 allele of cystic fibrosis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1995;96:2051–2064. doi: 10.1172/JCI118253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Heeckeren AM, Schluchter MD, Drumm ML, Davis PB. Role of cftr genotype in the response to chronic pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection in mice. American journal of physiology Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2004;287:L944–952. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00387.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGovern TK, Robichaud A, Fereydoonzad L, Schuessler TF, Martin JG. Evaluation of respiratory system mechanics in mice using the forced oscillation technique. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2013:e50172. doi: 10.3791/50172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu L, Cai BQ, Zhu YJ. Pathogenesis of cigarette smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and therapeutic effects of glucocorticoids and n-acetylcysteine in rats. Chinese medical journal. 2004;117:1611–1619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knudsen L, Weibel ER, Gundersen HJ, Weinstein FV, Ochs M. Assessment of air space size characteristics by intercept (chord) measurement: An accurate and efficient stereological approach. Journal of applied physiology. 2010;108:412–421. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01100.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrison AN, Regelmann WE, Zirbes JM, Milla CE. Longitudinal assessment of lung function from infancy to childhood in patients with cystic fibrosis. Pediatric pulmonology. 2009;44:330–339. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis SD, Fordham LA, Brody AS, Noah TL, Retsch-Bogart GZ, Qaqish BF, Yankaskas BC, Johnson RC, Leigh MW. Computed tomography reflects lower airway inflammation and tracks changes in early cystic fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2007;175:943–950. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-343OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aurora P, Bush A, Gustafsson P, Oliver C, Wallis C, Price J, Stroobant J, Carr S, Stocks J London Cystic Fibrosis C. Multiple-breath washout as a marker of lung disease in preschool children with cystic fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2005;171:249–256. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200407-895OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hantos Z, Daroczy B, Suki B, Nagy S, Fredberg JJ. Input impedance and peripheral inhomogeneity of dog lungs. Journal of applied physiology. 1992;72:168–178. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.1.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sobonya RE, Taussig LM. Quantitative aspects of lung pathology in cystic fibrosis. The American review of respiratory disease. 1986;134:290–295. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.2.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kent G, Iles R, Bear CE, Huan LJ, Griesenbach U, McKerlie C, Frndova H, Ackerley C, Gosselin D, Radzioch D, O’Brodovich H, Tsui LC, Buchwald M, Tanswell AK. Lung disease in mice with cystic fibrosis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1997;100:3060–3069. doi: 10.1172/JCI119861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen JC, Lundblad LK, Bates JH, Levitzky M, Larson JE. The “goldilocks effect” in cystic fibrosis: Identification of a lung phenotype in the cftr knockout and heterozygous mouse. BMC genetics. 2004;5:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bazett M, Haston CK. Airway hyperresponsiveness in fvb/n delta f508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator mice. Journal of cystic fibrosis : official journal of the European Cystic Fibrosis Society. 2014;13:378–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bonora M, Bernaudin JF, Guernier C, Brahimi-Horn MC. Ventilatory responses to hypercapnia and hypoxia in conscious cystic fibrosis knockout mice cftr. Pediatric research. 2004;55:738–746. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000117841.81730.2B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou Z, Duerr J, Johannesson B, Schubert SC, Treis D, Harm M, Graeber SY, Dalpke A, Schultz C, Mall MA. The enac-overexpressing mouse as a model of cystic fibrosis lung disease. Journal of cystic fibrosis : official journal of the European Cystic Fibrosis Society. 2011;10(Suppl 2):S172–182. doi: 10.1016/S1569-1993(11)60021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoegger MJ, Fischer AJ, McMenimen JD, Ostedgaard LS, Tucker AJ, Awadalla MA, Moninger TO, Michalski AS, Hoffman EA, Zabner J, Stoltz DA, Welsh MJ. Impaired mucus detachment disrupts mucociliary transport in a piglet model of cystic fibrosis. Science. 2014;345:818–822. doi: 10.1126/science.1255825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun X, Olivier AK, Liang B, Yi Y, Sui H, Evans TI, Zhang Y, Zhou W, Tyler SR, Fisher JT, Keiser NW, Liu X, Yan Z, Song Y, Goeken JA, Kinyon JM, Fligg D, Wang X, Xie W, Lynch TJ, Kaminsky PM, Stewart ZA, Pope RM, Frana T, Meyerholz DK, Parekh K, Engelhardt JF. Lung phenotype of juvenile and adult cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-knockout ferrets. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2014;50:502–512. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0261OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stoltz DA, Meyerholz DK, Pezzulo AA, Ramachandran S, Rogan MP, Davis GJ, Hanfland RA, Wohlford-Lenane C, Dohrn CL, Bartlett JA, Nelson GAt, Chang EH, Taft PJ, Ludwig PS, Estin M, Hornick EE, Launspach JL, Samuel M, Rokhlina T, Karp PH, Ostedgaard LS, Uc A, Starner TD, Horswill AR, Brogden KA, Prather RS, Richter SS, Shilyansky J, McCray PB, Jr, Zabner J, Welsh MJ. Cystic fibrosis pigs develop lung disease and exhibit defective bacterial eradication at birth. Science translational medicine. 2010;2:29ra31. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]