Abstract

This study examined patterns of: (1) observed racial socialization messages in dyadic discussions between 111 African American mothers and adolescents (M age = 15.50) and (2) mothers’ positive emotions displayed during the discussion. Mothers displayed more advocacy on behalf of their adolescents in response to discrimination by a White teacher than to discrimination by a White salesperson. Mothers displayed consistent emotional support of adolescents’ problem solving across both dilemmas but lower warmth in response to the salesperson dilemma. Findings illustrate evidence of the transactional nature of racial socialization when presented with adolescents’ racial dilemmas. The role of adolescent gender in mothers’ observed racial socialization responses is also discussed. A framework for a process-oriented approach to racial socialization is presented.

Keywords: racial socialization, parent-adolescent communication, adolescence, parenting

Racial socialization, defined as “parental practices that communicate messages about race or ethnicity to children” is a critical aspect of parenting African American children (Hughes & Chen, 1999, p.468; Lesane-Brown, 2006). Extensive theoretical advancement that articulated the dimensions of racial socialization have occurred over the past 30 years (Bowman & Howard, 1985; Lesane-Brown, 2005; Peters & Massey, 1983; Sanders Thompson, 1994; Stevenson, Cameron, Herrero-Taylor, & Davis, 2002; Thornton, Chatters, Taylor, & Allen, 1990). Moreover, several instruments have been developed that assess the degree to which African American parents convey specific content about racial issues to children (e.g., cultural socialization, preparation for bias, cultural mistrust). However, there is a paucity of research that captures the process of racial socialization. The research described in this article blends theory from communication studies with existing racial socialization theory to describe mothers’ observed behavior in response to adolescent racial dilemmas. We will focus on parental strategies for conveying messages rather than the content itself and detail the emotional and ecological context of parent-adolescent communication about race.

Racial Socialization as a Process: A Relational Communication Approach

Hughes and Chen (1999) stated that racial socialization is not only dyadic (bidirectional), it consists of intentional and spontaneous communication by parents to children. Parents often have specific ideas or messages they wish to communicate on this topic. Children also raise questions about race with their families based on events they observe and experiences they have. Applying observational methods to parent-adolescent conversations about racial issues can illuminate the ways the relationship shapes the racial socialization process (Coard, Pasamonte, & Smith, 2009; Frabutt, Walker, & MacKinnon-Lewis, 2002; Johnson, 2005). Observing and analyzing actual conversations about racial issues also provides an opportunity for new constructs and processes to be identified that go beyond current knowledge gleaned from data based on questionnaires, interviews, and focus groups (Johnson, 2005).

We use elements of Relational Communication Theory (RCT) to frame racial socialization as a family process (Rogers, 2006). RCT is a family communication theory that argues that communication between family members is a dynamic process co-created by family members. RCT acknowledges that family communication consists of the (1) explicit content of the communication and (2) the relational context of the communication. The relational history can imbue the content with meaning in specific ways that vary across families. Moreover, RCT also acknowledges that family members can have different perspectives on the same communication content. Specifically, there is the intended message and the received message between family members, both of which comprise the relational meaning of the communication according to RCT. Moreover, the bidirectional exchange between family members represents the mutual creation of the meaning of communication among family members (Rogers, 2006), which meshes well with theoretical assertions that racial socialization is bidirectional.

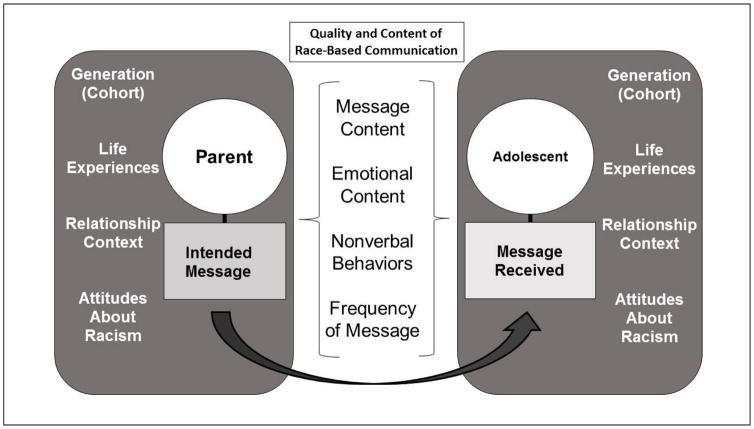

Relying upon Hughes et al., (2006) theory of racial-ethnic socialization and Relational Communication Theory (2006), we propose a process-based model to explain family communication processes involved in content about racial issues. In Figure 1, we provide a conceptual model of parent-adolescent communication about race. The model considers the nature of relationship and the communication between adolescents and their parents as the context for racial socialization. Communication about racial issues consists of the actual content of the message, the parents’ intended message, and the message received by the adolescent. The nonverbal behaviors that accompany a message and the emotional tone of a discussion about racial issues (e.g., warm, conflictual) can affect whether and how adolescents receive the message content. Generational differences between the adolescent’s and the parent’s life experiences regarding race (Brown & Lesane-Brown, 2006) can also affect the content of the discussion. Moreover, contemporaneous events in the lives of African American families that have overt or covert racial undertones can trigger discussions between parents and children (Juang & Soyed, 2014).

Figure 1.

Racial socialization as a process: A conceptual model.

Observational Research Measuring Racial Socialization

A small number of studies have used an array of observational methods with African American families to capture racial socialization, and video-recorded methods are rare. Caughy and colleagues (2002) introduced the Africentric HOME Inventory, an observational tool designed to assess the number of cultural artifacts in African American households and is considered a measure of cultural socialization. Johnson (2005) video recorded African American parents and school-aged children discussing her Racial Stories Task (RST; Johnson, 1996). The RST involves presenting a series of vignettes about racial dilemmas for African American school-aged children and instructing parents and children to discuss how to respond to them. Her coding system provides instruction on how to code parents’ content-based responses to the dilemmas as well as attention to the broader processes embedded in those responses. The Parent-Child Race Related Observational Measure (PC-ROM; Coard & Wallace, 2001) involves 3 interrelated tasks designed to assess delivery of racial socialization content for African American parents and young children (ages 3–8). It involves videotaping and transcribing parents’ responses to each task and can be used in clinical and research contexts.

Both the Racial Stories Task I and II and the PC-ROM involve extensive documentation and analysis of parents’ and children’s responses to racial dilemmas that give a rich detailed portraits of the process of racial socialization for African American youth of different ages. A full review of both measures is beyond the scope of this article. However, they both capture the idea that racial socialization is a process, and that the wide array of race-based experiences African American children and their families encounter can trigger a wide array of responses not easily captured by self-report measures.

Parents’ Responses to Children’s Experiences with Racial Discrimination

In this article, we describe three types of parental communication strategies that we observed with respect to how African American parents execute racial socialization with their adolescent children. Other observational methods emphasize assessment of the frequency and qualitative content (e.g., preparation for bias, racial pride) of racial socialization discussions at the granular level. We focus more specifically on the processes in terms of presence of certain parenting strategies delivered in racial socialization discussions and the degree to which parents vary the use of specific strategies when addressing different racial dilemmas their children experience. These are parental suggestions for addressing racial dilemmas, parental advocacy on behalf of their children, and parent emotional supportiveness of children who are responding to racial dilemmas.

Parental suggestions to children for addressing discrimination

We define parental suggestions as any statements parents make to children designed to help children respond to racial discrimination. Most existing studies focus more on the content that parents share. Parental suggestions on how to respond and manage discrimination include but are not limited to messages teaching children about black history, the importance of getting an education, the importance of racial pride, confirmation of the existence of racial bias in society, embracement of mainstream values, or teaching children not to trust other racial-ethnic groups (Stevenson et al., 2002). Parental suggestions also encompass sharing strategies for children to implement behaviorally and for managing emotions in response to a racially stressful situation (e.g., staying in control of one’s emotions (Thomson & Blackmon, 2015). Johnson (2005) describes a similar set of constructs that capture the type of strategies or suggestions deploy. Our conceptualization focuses more on the frequency of any type strategies rather than a particular type. Previous research has shown that parents vary in the content of their racial socialization messages (e.g., parental suggestions) shared with children or adolescents, but it has generally not examined in detail whether there is variation in response to specific racially stressful situations to which their children are exposed (Johnson, 2005). Some racially stressful events may trigger more suggestions from parents, whereas other events may elicit comparably fewer suggestions.

Parental advocacy in response to children’s discriminatory experiences

Parental advocacy is defined as statements parents make about how they, as parents, would address racially stressful dilemmas their children face. There is an extensive literature addressing research and policy regarding parents’ advocacy on behalf of children with disabilities, giftedness, and in special education (Duquette, Orders, Fullarton, & Robertson-Grewal, 2011; Trainor, 2010). Only a few studies address parental advocacy in response to potential racial discrimination. One qualitative study focused on the experiences of parents of gifted African American youth ages 9 to 16 revealed that in advocating for appropriate educational accommodations for their children often meant addressing individual incidents of racial discrimination by teachers and a general institutional resistance to acknowledging their children’s academic talents (Huff, Houskamp, Stanton, & Tavegia, 2005). Holman’s (2012) recent interview-based qualitative study of 22 middle-class African American mothers (children ages 13–18) noted that mothers often implemented advocacy on their children’s behalf in response to racial discriminatory incidents their children shared with them. Incidents described often included school settings and incidents with the police. Mothers advocated on their children’s behalf via requests for meetings with teachers and school administrators and also, changing the child’s school if the original school was deemed racially hostile for their child.

As these studies reveal, it is plausible to assume that a substantial number of African American parents engage in some form of advocacy in response to children’s experience with racial discrimination. To date, the concept has not emerged as a racial socialization strategy in the literature. Further research is needed to articulate the degree to which parents use parental advocacy in response to children’s discrimination experiences and how advocacy varies by the types of incidents children experience.

Positive Emotions in the Context of Racial Socialization

The role of parental positive emotions has received limited attention in the racial socialization research literature to date. However, previous research has indicated that parental positive emotions do matter in disentangling the impact of specific racial socialization messages on youth (Cooper & McLoyd, 2011; Elmore & Gaylord-Harden, 2012; Frabutt et al., 2002; Rogers, 2006). Parental warmth is an affective component of the parent-child relationship and is the context in which racial socialization occurs. Parental supportiveness is defined as the degree to which parents exhibit direct support of their children’s efforts to address their experiences with racial discrimination. Consistent with a process-oriented perspective on racial socialization, we assume that parents with positive relationships with their children should also be exhibit higher support of their children’s efforts to address racial discrimination. Our study is distinct from previous investigations considering parental emotion because we consider both global maternal warmth and supportiveness in response to children’s efforts to respond to racial dilemmas as separate constructs.

Racial socialization and adolescent gender

Research investigating gender differences in racial socialization patterns has yielded conflicting findings, with a small number of studies detecting gender differences in content delivered and in relationships to developmental outcomes (Brown, Linver, Evans, & DeGennaro, 2009; Caughy, Nettles, & Lima, 2011; Smalls & Cooper, 2012; Varner & Mandara, 2013). In studies that have detected gender differences, research has demonstrated that, regardless of child age, African American parents deliver more messages to boys about preparation for bias and about the realities of racial barriers in society than to girls (Bowman & Howard, 1985; McHale et al., 2006; Thomas & Speight, 1999). Across child age, parents of girls have been found to deliver more messages designed to promote cultural socialization or to promote racial/cultural pride than parents of boys (Lesane-Brown, Brown, Tanner-Smith, & Bruce, 2010; McHale et al., 2006). In one study, African American parents of first graders who were the least likely discuss any racial issues were much more likely to be the parents of sons than the parents of daughters (Caughy et al., 2011).

In light of the small number of studies that have examined gender differences in racial socialization processes specifically, we offer some speculations about linkages between maternal suggestions and advocacy and child gender. It is possible that mothers display varying degrees of parental advocacy and suggestions to sons and daughters. African American boys are targeted by specific forms of racial discrimination more often (Greene, Way, & Pahl, 2006; Smith-Bynum, Lambert, English, & Ialongo, 2014). As a result, mothers of sons may give more suggestions for addressing racial dilemmas than mothers of daughters. Similarly, they may give more advocacy statements because they believe sons need more parental intervention in addressing the racial dilemmas than mothers of daughters. Alternatively, the gender intensification hypotheses posits that mothers may exhibit more advocacy and suggestions to daughters than to sons as a reflection of efforts to promote more independence and autonomy in sons (Hill & Lynch, 1983; Holmbeck, Paikoff, & Brooks-Gunn, 1995).

The Present Study

Given that racial socialization is bi-directional and at times, spontaneous, (Hughes, Rodriguez, et al., 2006), we believed observing mothers and adolescents engaged in the active process of racial socialization would yield useful information about: (a) how parents actually convey these messages to children and (b) how they model problem-solving, and (c) whether different racial dilemmas would elicit differential responses from parents. Moreover, it would simultaneously capture information about the relationship context of parent-adolescent communication about race in a process-oriented manner. Including 2 vignettes permitted examination of African American youths’ experiences with racial discrimination in two common arenas: schools and public spaces (Chavous, Rivas-Drake, Smalls, Griffin, & Cogburn, 2008; Fisher, Wallace, & Fenton, 2000).

Extant research indicates that African American youth experience racial discrimination in schools and public spaces on a regular basis (Greene et al., 2006; Seaton, Caldwell, Sellers, & Jackson, 2008; Seaton & Douglass, 2014). The first vignette, The Teacher, described an academically talented African American adolescent enrolled in a predominantly White school who received an unfair grade by a White teacher. The second vignette, The Mall, described a situation in which an African American adolescent is treated rudely by a White salesperson after trying on an expensive garment in a department store located in an affluent White suburb. In this research, we seek to examine whether mothers differ in their deployment of racial socialization strategies when their children experience different types of discrimination.

We pursued 3 research questions focused on racial socialization processes exhibited by African American mothers in response to the The Teacher and The Mall.

Do mothers’ observed racial socialization (e.g., suggestions, advocacy) differ in response to specific racial dilemmas presented in each vignette?

Does gender moderate the relation between mothers’ observed racial socialization behaviors (e.g., suggestions, advocacy) and vignette content?

Do mothers observed positive emotions (e.g., warmth, supportiveness) differ in response to their adolescents’ racial dilemmas?

Method

Sample

Data were collected from 111 African American mother-adolescent dyads residing in the Washington, DC metropolitan area between 2010 and 2011. All participants spoke English. Mothers ranged in age from 29 to 64 (M age = 44.18). The sample’s median education level is associate’s degree. The median household income is $60,000 to $69,000. Annual household income ranged from less than $5,000 to $100,000 or greater per year. Approximately one-third (28%) of the sample had incomes of $100,000 or greater. Approximately 95% of the sample identified as African American, followed by 3% for Afro-Caribbean, 1.5% for Biracial/Multiracial. Married mothers comprised 38% of the sample, followed by 31% who had not married, 22% who were divorced, 4.5% separated, and 3% who were widowed. Two mothers did not report their marital status. Of those mothers who were not married, 6 reported cohabiting with a romantic partner.

A total of 94% of the female caregivers in our studies were the biological mothers of the participating adolescents. Four adoptive mothers (3%), two stepmothers (1.5%) and 1 aunt (1%) participated in the study. Most mothers (78%) were employed. Adolescents ranged in age from 14 to 17 (M age = 15.50). Girls comprised 55% of the sample. One adolescent did not report a gender. Ninety percent of the sample was African American, 3% was Afro-Caribbean, 4.5% was Biracial/Multiracial, and 1 (.7) endorsed Black South American.

Three cases had to be eliminated from the analyses. One family was eliminated because the child did not meet the age criterion. One interview was terminated before it was completed due to concerns about respondents’ understanding of informed consent. A third case was removed as the family repeated the study twice. Only their initial data were used in the present study.

Measures

Observed racial socialization communication

The Racial Socialization Observational Task and Coding System (Smith-Bynum, 2008, Smith-Bynum & Usher, 2004; Smith-Bynum, Usher, Callands, & Burton, 2005) used in the present study was developed to assess the dynamic aspects of the racial socialization process between parents and adolescents (Hughes & Chen, 1999; Hughes, Rodriguez, et al., 2006). Trained staff presented parents and adolescents with a set of audiotaped vignettes that describe an adolescent addressing racial discrimination followed by instructions to parents and adolescents to discuss how they would respond to the scenario. As such, the task focuses more on preparation for bias as described by Hughes and Chen (1999) with specific emphasis on how to reason through and respond to perceived racial bias in interpersonal situations. Piloted with samples involving both mother-adolescent and father-adolescent dyads (Smith-Bynum & Usher, 2004), the task is designed to elicit conversations about addressing racial discrimination that approximate actual conversations between parents and adolescents about potential racial discrimination. Three parent socialization responses to vignettes emerged: (1) parent suggestions to adolescents for addressing the dilemma; (2) parent as advocate; (3) parent supportiveness of the adolescent’s efforts to solve the problem.

The Racial Socialization Observational Task and Coding System (Smith-Bynum, M. (2008, Smith-Bynum & Usher, 2004; Smith-Bynum, Usher, Callands, & Burton, 2005) was used to assess conversations between mothers and adolescents about potential racial discrimination. Designed to elicit processes embedded in racial socialization as outlined by Hughes and Chen (1999), the task involves two 5-minute discussions between parents and children about how to address dilemmas presented in two vignettes each family listened to on a digital device. At the end of the discussion, mothers and adolescents were given the following instruction: “Pretend as if the situation happened to you and your family. How would you respond if the situation happened to you and your family?”

Two of the vignettes with White adults involved events occurring in school and one in a shopping mall. The vignettes were intended to elicit discussions about how African American parents and adolescents would interpret and respond to racial dilemmas common to African Americans youth (Spencer, 1985). The first vignette, entitled The Teacher, involved a talented student receiving an unfair grade on an assignment from a White teacher (Johnson, 2001). The second vignette, entitled The Mall, involved an African American adolescent experiencing rude treatment from a White salesperson (Fisher, Wallace, & Fenton, 2000). Both vignettes were also matched on gender with that of the adolescent participant. The vignettes were presented in a counterbalanced order and each 5-minute discussion was videotaped. A full description of the development of the measure is available from the first author.

Maternal suggestions for addressing discrimination

This behavior addressed mothers’ suggestions or directions to the adolescent about how to handle the situation. Mothers made suggestions that included behaviors adolescents should execute (Johnson, 2001; Smith-Bynum & Usher, 2004; Smith-Bynum, Usher, Callands, & Burton, 2005) to address the situation (e.g., “Call me on your cell phone”; “Ask the teacher to explain the grade to you.”) and suggestions for managing emotions (e.g., “Try to stay calm.). Raters counted the number of suggestions mothers made within each 30-second interval across the full length of each vignette discussion. The 30-second timeframe increased the reliability of the coding (C. S. Tamis-LeMonda, personal communication, May 12, 2012). This number constituted the frequency in which mothers made suggestions in regard to each vignette. The frequency of suggestions from both vignette discussions were summed for the analyses.

Mother as advocate

This behavioral code consisted of strategies in which mothers described the ways they take an active role in helping the adolescent cope with the situations described in the vignette, both of which involve the adolescent’s interaction with a White adult. Raters counted the number of individual ways a parent discussed serving as an advocate for the adolescent for each 30-second interval. Examples of advocacy in this context include but are not limited to the parent requesting a meeting with the White adult involved in the vignette, the parent asking to speak with a manager or school principal, or the parent contacting the media to report an incident of racial discrimination. The distinctive feature of this behavior is the parent’s behavior in response to the situation on behalf of their child. The statements about parental advocacy were counted within each 30-second interval. The number of comments across all of the 30-second intervals were added together to index the extent of parental advocacy within each discussion. We used sum scores for both The Teacher and The Mall vignettes.

Maternal supportiveness of adolescent responses

It is a measure of maternal emotion measured by the Racial Socialization Observational Task and Coding System (Smith-Bynum & Usher, 2004; Smith-Bynum, Usher, Callands, & Burton, 2005). It is defined as the extent to which the parent expresses direct support of the adolescent’s ideas or makes statements designed to elicit the adolescent’s ideas about how to cope with the situation in each vignette (e.g., “That’s a great idea! I never would have thought of that”). Mothers might also nod or give other nonverbal indicators of support or agreement with the adolescent’s efforts to solve the problem (e.g., smiling, enthusiasm, interest, pleasant facial expression). Mothers rated as unsupportive disparaged the adolescents and/or their ideas (e.g., “That [idea] is just stupid.”). They might also disagree with or put down the adolescent’s strategy in absence of an effort to teach or expand upon the adolescent’s original strategy or solution. Nonverbal indicators of a lack of support or active contempt for the adolescent’s ideas were also considered unsupportive. Examples of nonverbal indicators included frowns, scowls, rolling eyes, folded arms, and defensive body posture. Raters also attended to parents’ tone of voice and facial expressions (e.g., aggressive or condescending tone, sarcasm). Mothers were rated on a 5-point scale from “1” for Very Unsupportive to “5” for Very Supportive for each 30-second interval across each vignette. The mean score across all intervals was calculated for each vignette to index the average degree of maternal supportiveness for each.

Maternal warmth

Maternal warmth was measured by the warmth code in the African American Families Macro-coding Manual (Smetana & Abernathy, 1998), a coding system of behavioral interaction in families that was adapted for use with African American families. African American coders were instructed to rate mothers on the degree of verbal and nonverbal expressions of warmth. Verbal expressions include a family member’s statements of love, care, consideration for the other family member. It also included family members’ expression of interest in another member. Nonverbal expressions of warmth consisted of a family members’ eye contact, mutual laughter, nodding, smiling, leaning towards the family member, gazing, sitting close to another member. It also consisted of “touching” a family member “affectionately, playfully, or nurturantly” (p. 10). Raters scored mothers’ warmth within each 30-second interval of both vignette discussions on a 5-point scale with higher scores indicating higher warmth (1 = Absence of Warmth, 2 = Low Warmth, 3 = Somewhat Warm, 4= Fairly Warm, and 5 = Very Warm). The ratings for each interval were averaged separately for each vignette.

The response options for scores 1 and 2 reflect modifications to the original 5-point scale. Smetana and Abernathy (1998) originally labeled 1 as “Very Cold” and 2 as “Fairly Cold.” During the calibration phase, raters observed that a cold emotional tone did not seem to reflect the emotional tone of the families interviewed for the study who were low on warmth. Raters often observed that when less warmth was present, negative emotion was also present (e.g., anger, hostility). To avoid contaminating ratings of low warmth with other emotions, a score of “2” was changed from representing “Cold” to “Low Warmth.” We also added the phrase, “or rather, expresses it [warmth] infrequently” to the description of Low Warmth. A score of “1” was changed from “Very Cold” to “Absence of Warmth.” The words “moderate degree” were added to the description for a rating of “3,” characterized as “Somewhat Warm.” These revisions enhanced the clarity of the codes. This procedure has demonstrated reliability with inter-rater reliability scores of .80 to .95 in a sample of middle-class African American families (Smetana, Abernethy, & Harris, 2000).

Procedure

Data collection

Research staff placed advertisements in a free daily newspaper and other free monthly publications aimed specifically at parents that are widely available throughout the metropolitan area. The advertisements were constructed in a way to appeal to African American mothers and other female caregivers. This included the use of an attractive photograph of an African American family as well as a project logo. In most cases, the advertisements also alerted potential participants about a Facebook page for the project that contained a Frequently Asked Questions page and information about the research team and the first author. Potential participants were then instructed to call or email the project office for a formal telephone screening and also, to schedule a time for the interview. During the initial telephone contact, a research staff person explained the details of the informed consent process as well as provided specific details about items on the study questionnaire deemed sensitive (e.g., drug use, truancy, stealing, sexual behavior) to reduce the potential for discomfort on the part of the family and potential coercion of the adolescent to enroll in the study.

Data were collected by trained research team comprised primarily of African American undergraduates (86%). Two interviewers collected data in each family’s homes and each team had at least 1 African American member. After greeting the family, the interviewers completed the informed process. One interviewer reviewed the informed consent process with mothers. To reduce the potential for coercion, a second interviewer reviewed the informed assent process with the adolescent in a room separate from the mother.

After informed consent and assent were obtained, the interviewer assigned to the mother administered a battery of self-report questionnaires on an array of topics (e.g., parenting, parent-child relationship quality, racial socialization, discrimination experiences, racial identity, psychological functioning). The second interviewer administered self-report measures to adolescents on similar topics. One interviewer explained the Racial Socialization Observational Task to the mother-adolescent dyads while the second interviewer managed the equipment involved in the task. Both interviewers stepped outside the room while the two discussions about the vignettes occurred. The presentation of the questionnaire portion and the observational task were counterbalanced. Moreover, the interviewers also counterbalanced the presentation of each of the vignettes in the observational task. After the data were collected, the interviewers paid family received $50.00 for participating. The entire process, which included informed consent, equipment set-up, task execution, questionnaire completion, payment, and debriefing took approximately 2 hours.

Data coding

A team of 4 African American coders completed extensive training in coding the video segments. The team spent approximately 15 hours a week in training over a 4-month period. During the first month, the team calibrated the ratings for each variable. When disagreements occurred, the team viewed the video clips as a group and discussed the discrepancies. The first author clarified the codes for the team by explaining how concepts in the codebook should be applied. As noted, raters raised concerns about some aspects of the warmth behavioral code. The team identified an initial group of specific videos of families with warmth levels were somewhere below the midpoint and viewed the tapes as a group. Discussions about the videos yielded a consensus that the original labels assigned to lower levels of warmth did not adequately capture the emotions being displayed by the families. The team identified new labels for the lower scores.

The families were instructed to discuss both vignette for 5 minutes each. Coders were instructed to code each behavior in 30-second intervals. As noted, emotion codes (warmth, maternal supportiveness) were coded on a 5-point Likert-type scale within each interval. Coders counted the number of racial socialization comments (parental advocacy, parental suggestions) within each interval.

Forty percent of the videos of discussions about The Teacher vignette received a rating by a second coder. Intra-class correlations (ICC) were used to assess reliability between two raters’ coding of variables assessed within the teacher vignette: parent suggestions, support, advocacy, and warmth, and teen warmth. Using SPSS, a two-way mixed effect model with absolute agreement was used for all ICC analyses (Field, 2009; Shieh, 2012; Shrout & Fleiss, 1979). The ICC was high for parental suggestions, ICC = .84, p < .001, 95% CI [.65, .92], parental advocacy ICC = .92, p < .001, 95% CI [.83, .96], parental supportiveness ICC = .97, p < .001, 95% CI [.94, .99]. ICC was adequate for parental warmth ICC = .70, p < .01, 95% CI [.36, .86].

Results

Univariate and bivariate statistics were performed on all variables. Means and standard deviations for study variables are presented in Table 1. As can be seen in Table 1, mothers’ averaged about 3 comments about their own parental advocacy across the two vignettes. On average, mothers made 7 suggestions to their adolescents about how to cope with the situations in the vignettes. Out of a potential range of 1 to 5, mothers were slightly below the midpoint in terms of warmth for both vignettes. Maternal suggestions to adolescents for responses to the dilemmas in the vignette were positively correlated with maternal supportiveness for The Teacher (r = .31, p ≤ .001) and The Mall (r = .38, p ≤ .01). Maternal suggestions were positively correlated with maternal warmth on for The Mall vignette but not for The Teacher. Within The Teacher, maternal supportiveness was strongly correlated with maternal warmth (r = .78, p ≤ .01). A similar pattern was detected between these variables for The Mall (r = .81, p ≤ .001).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables by Vignette Content

| The Teacher | The Mall | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | |

| Maternal Advocacy | 4.06 (3.11) | 0 – 14 | 1.23 | 0–8 |

| Maternal Suggestions | 3.45 (3.47) | 0–18 | 3.93 (3.30) | 0–16 |

| Maternal Supportiveness | 3.18 (.24) | 2.66–4.00 | 3.17 (.21) | 2.43–3.78 |

| Maternal Warmth | 2.90 (.59) | 1.10–5.00 | 2.89 (.59) | 1.10–5.00 |

Note. Maternal Advocacy = Mothers as Advocate. Maternal Suggestions = Mothers’ suggestions for addressing. Maternal Supportiveness = Mothers’ supportiveness of adolescent addressing discrimination.

Stability of mothers’ behaviors and emotions

Prior to addressing the formal research questions, we examined the stability of mothers’ observed racial socialization and positive emotions stable across the two discussions, we conducted correlations with the study variables across vignettes. Positive correlations were detected in observed racial socialization behaviors and positive emotions across vignettes. The number of suggestions offered during The Teacher was positively correlated with the number suggestions offered during The Mall (r = .36, p ≤ .001). However, mothers’ advocacy behaviors were not correlated across the two discussions about the vignettes. In terms of emotions displayed, maternal supportiveness (r = .74, p ≤ .0) and maternal warmth (r = .73, p ≤ .001) were both strongly and positively correlated across both vignettes.

Some behaviors also yielded significant correlations with other variables across vignettes. Mothers’ supportiveness during The Teacher showed a small positive correlation to their suggestions to their children during The Mall discussion (r = .30, p ≤ .01). Mothers’ warmth during The Teacher was also moderately positively correlated with their supportiveness during discussions about The Mall (r = .63, p ≤ .01). It was also positively correlated with the number of suggestions they made to their children albeit to a smaller degree (r = .22, p ≤ .05).

Model 1: Mothers’ racial socialization behaviors by vignette and gender

Next, we examined how mothers responded to the vignettes. We conducted a repeated measures ANOVA to answer the second research question. The first question examined whether mothers differed in the degree of observed racial socialization behaviors (e.g., suggestions, advocacy) in response to The Teacher and The Mall. The second research question examined whether gender moderates the relation between the two observed racial socialization and vignette content. The within-group factors in each analytic model consisted of racial socialization behavior and vignette content. Adolescent gender was included as a between-group factor.

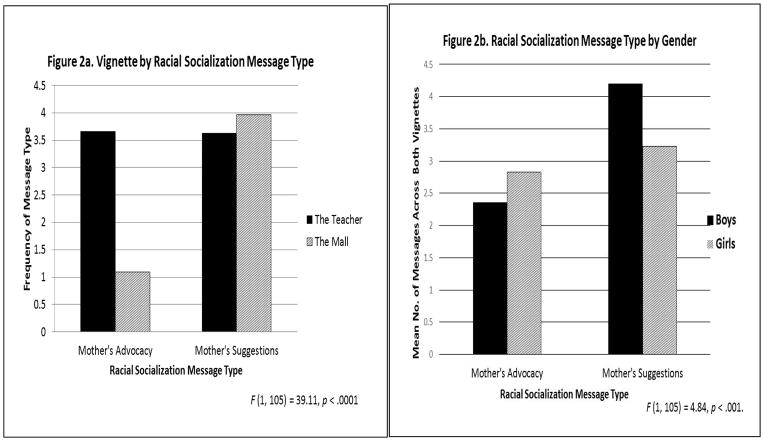

In Model 1, The Mauchly’s W test for nonequivalences of variance was significant. Therefore, F values from the Greenhouse-Geisser test are provided. The results indicated that there were main effects for racial socialization behavior, F (1, 105) = 11.42, p < .001, η = .10 and vignette content, F (1, 105) = 24.61, p < .001, η = .19. Mothers gave more total racial socialization statements in response to The Teacher vignette (M = 3.76) than to The Mall vignette (M = 2.54). Also, mothers made more suggestions (M = 3.74) than statements about how they would advocate on behalf of their child (M = 2.59). There was no main effect for gender, however.

Results from Model 1 also yielded 2 interactions. First, we detected a vignette X racial socialization measure interaction, F (1, 105) = 39.11, p < .0001, η = .27. The interaction indicated that mothers provided a similar number of suggestions across the two vignettes. However, they made fewer statements describing how they would advocate on behalf of their children in response to the dilemma presented in The Mall vignette as compared to The Teacher vignette (See Figure 2a). This pattern suggests that mothers observed less need to intervene in The Mall as compared to The Teacher. The second interaction occurred between racial socialization behavior and adolescent gender, F (1, 105) = 4.84, p < .001. The results indicated that mothers delivered more messages about advocacy to girls as compared to boys. In contrast, mothers gave suggestions about how to cope to boys than to girls. The effect size for this pattern was quite small, η = .04. These results are displayed graphically in Figure 2b.

Figure 2.

Graphic depiction of interactions from Model 1. Figure 2a displays the interaction of Vignette X Racial Socialization Message Type. Figure 2b displays the interaction of Racial Socialization Message Type X Gender.

Note. Mother’s Advocacy = Mother’s as advocate. Mother’s Suggestions = Mother’s Suggestion for addressing discrimination.

Model 2: Mothers’ positive emotions by vignette

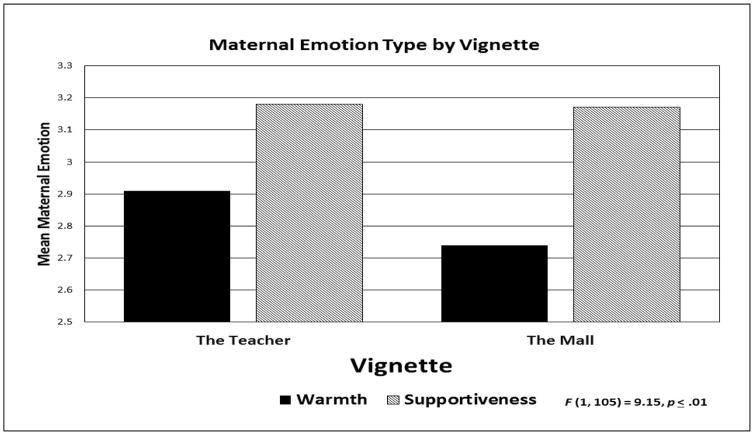

The third research question addressed how mothers’ positive emotions varied across the 2 vignettes and whether gender served as a moderator of mothers’ responses. A repeated measures ANOVA examined the impact of mothers’ observed positive emotions during the discussions (warmth, supportiveness) in combination with vignette type and adolescent gender. As with Model 1, the Mauchly’s W test for nonequivalences of variance was significant. As a result, F values for the Greenhouse-Geisser test are provided here as well. The results yielded a main effect for maternal positive emotions, F (1, 105) = 54.72, p < .0001, η = .34, and vignette, F (1, 105) = 7.19, p < .01, η = .06. Of the two indicators of maternal positive emotions observed, post-hoc analyses indicated that mothers displayed higher levels of supportiveness of adolescents’ efforts to address the dilemma relative to general warmth across both vignettes. A main effect for vignette indicated that The Teacher vignette (M = 3.04) elicited a slightly stronger emotional response from mothers overall than The Mall vignette (M = 2.96). A small maternal emotion X vignette interaction also emerged, F (1, 105) = 9.15, p ≤ .01, η = .08. The interaction revealed that maternal supportiveness in response to adolescents’ efforts to solve the problem was consistent across vignettes. However, mothers’ general warmth was lower in discussions about The Mall than in The Teacher.

Discussion

We sought to capture the processes by which African American mothers execute racial socialization behaviors and the positive emotions expressed in discussions about racial bias using observational methods. For this study, we focused on the frequency of two types of racial socialization communication that African American mothers made in response to racial discrimination from White American adults: suggestions about how to handle racial discrimination and statements about their advocacy with White adults on behalf of their adolescent children. Results were consistent with a process-oriented conceptualization of racial socialization. Specifically, mothers’ racial socialization responses appear to be driven by the specific experiences with racial dilemmas their adolescents encounter (Hughes et al., 2006; Rogers, 2006).

Study results revealed further evidence of a process-oriented racial socialization in several ways. African American mothers delivered more total racial socialization statements in response to The Teacher than to The Mall. Mothers also varied in the degree to which they exhibited advocacy and observed warmth expressed across the 2 vignettes. Lastly, a small interaction of racial socialization message type by adolescent gender difference indicated mothers of sons and mothers of daughters responded differently with respect to the number of suggestions to their children about how to cope with the dilemmas as compared to the number of advocacy efforts mothers described in their discussions.

We found that mothers modified their racial socialization responses to racial discrimination presented in The Teacher and The Mall. While mothers’ positive emotions (supportiveness, warmth) were highly stable across both vignettes, they generated a higher number of total suggestions for adolescents to implement in response to the vignettes than statements describing their parental advocacy in response to the two scenarios (The Teacher, The Mall). Moreover, mothers responded with statements about advocacy at a higher rate on average in response to The Teacher vignette in comparison to The Mall. These results also indicate that mothers were able to maintain a consistent degree of emotional support towards their adolescents’ efforts to address racial dilemmas while also customizing their racial socialization responses to the type of racial discrimination to each vignettes.

Additionally, mothers’ positive emotions exhibited towards their adolescents may also reflect the nature of the events in the vignettes. Though mothers in our study were consistently supportive of youth’s efforts to solve the dilemmas across both vignettes, mothers’ general warmth dropped off slightly during discussions about The Mall. The reasons for the difference in levels of maternal warmth are unclear. While no racial epithets were included in The Mall vignette, the hostile treatment by the salesperson was designed to be overtly negative. Anecdotally, we observed that mothers may have displayed lower levels of warmth because they also were managing their own negative emotional reactions to the negative event described in The Mall (Peters & Massey, 1983). Examination of mothers’ negative emotions was beyond the scope of our study. We plan to consider the management and expression of positive and negative emotions by African American families coping with racial dilemmas in future research.

The teacher’s behavior towards the protagonist in The Teacher was more ambiguous. This ambiguity appeared to elicit more elaborated and nuanced racial socialization responses from mothers due to their concerns about long-term interactions with a teacher who may be racially biased (Holman, 2012). These more elaborated responses may reflect mothers’ efforts maximize chances for fair treatment by the teacher. However, even though mothers may have been disturbed by the events in The Mall, they may have responded less intensively with advocacy responses if they believed the situation could be resolved by simply instructing their child to exit the situation. We did not count how often mothers instructed their adolescents to exit the situation in this study, but some mothers did instruct their adolescents to leave the store in this sample.

Our study results also yielded one small gender difference in mothers’ statements referencing suggestions for addressing racial bias and their advocacy for their children in situations. Specifically, mothers of sons made more statements consisting of suggestions across both situations than they did about advocacy. The reverse was true for mothers of daughters. The findings demonstrated limited evidence of the gender intensification hypotheses but in a slightly different way than expected (Hill & Lynch, 1983; Holmbeck, Paikoff, & Brooks-Gunn, 1995). Mothers of sons delivered more suggestions and fewer advocacy statements than mothers of daughters. This suggests that mothers of sons promote more autonomy in addressing some racial dilemmas than mothers of daughters, but only to a small degree.

Methods may also explain the small effect detected here. For instance, instructions to the families did not request that the dyads address the adolescent’s gender in their discussions. It is possible that gender dynamics may have been more pronounced if the instructions had asked the dyads to address adolescent gender specifically. We also tested only 2 scenarios. It is possible that mothers’ responses may be more or less pronounced in different situations (Thomas & Blackmon, 2015. Moreover, we only examined mothers in the present study. Fathers might engage suggestions and advocacy in different ways in response to their adolescents’ racial dilemmas.

Limitations

In addition to the limitations already noted about gender, other study limitations must be acknowledged. The sample size in this study is somewhat small. Researchers should note the variation in the effect sizes and place more weight on the larger effect sizes detected. These results should be replicated with a larger sample and in other parts of the U.S. We also tested only 2 scenarios focused on racial discrimination. Other scenarios involving racial discrimination might elicit a different combination of maternal responses.

Conclusions and Directions for Future Research

This study is one of the first studies of its kind to highlight the transactional nature of racial socialization in families of African American adolescents via observational methods. Use of observational methods in racial socialization research is still rare as illustrated by the low number of published studies employing these tools. While use of videos-based observational methods is increasing, development and validation of these measures is a lengthy, intricate process. However, our experience indicates that the more complex observational methods are worth the effort because of the increased insights they can provide researchers about the racial socialization process. Carving out a place for such an approach in the existing racial socialization literature is an enormous challenge as the observed racial socialization constructs do not always fit neatly into existing theoretical models. We propose that existing theory be expanded to account for new information yielded by measurement of observed processes embedded in delivery of racial socialization to reflect the findings reported here, and those reported by other investigators (Coard & Wallace, 2001; Johnson, 2005).

Consistent with a process orientation towards racial socialization, we further propose that parental suggestions and advocacy are at least two of the vehicles by which specific content involving racial socialization is deployed. While our measurement of these constructs is distinct in definition and operationalization, they share similarities with constructs identified by other investigators working with younger African American children (Coard & Wallace, 2001; Holman, 2012; Johnson, 2005), lending veracity to the notion that racial socialization is a process.

The field has already begun moving towards integrating racial socialization with general aspects of the parent-child relationship, and other parenting behaviors in understanding the role of parenting in African American child development (Cooper & McLoyd, 2011; Frabutt et al., 2002; Smalls, 2009). We argue that parental supportiveness of children’s efforts to address racial discrimination is a newly identified, meaningful aspect of the racial socialization process. Researchers should measure parental supportiveness in understanding the messages adolescents receive and whether they are able to use the coping strategies that parents provide (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999). Observational methods should be utilized more frequently in racial socialization research to help determine the best combination of parenting processes that help African American youth thrive.

Racial discrimination experiences are dehumanizing, stressful encounters that African American families must manage on a daily basis (Clark et al., 1999; Peter & Massey, 1985; Seaton et al., 2008). Moreover, current events magnify the reality that effective racial socialization can literally be the difference between life and death for some African American youth (Bassett, 2015). Mothers in this study had to manage their own emotions while guiding their adolescents through racially stressful dilemmas. They had to decide when to step in and assist and what suggestions to give their adolescents, even if hearing about the situations was highly distressing and upsetting. This is an enormously burdensome parenting task that requires delicate maneuvering and care to execute well (Bynum et al., 2008). Observational methods are well-suited to illuminating how African American parents should implement advocacy and suggestions and the circumstances in which they can be deployed for the greatest positive effect. This information can also move the field towards providing clear guidance to parents and clinicians regarding the best ways to deploy racial socialization effectively in today’s challenging times.

Figure 3.

Graphic depiction of interaction of maternal positive emotions by vignette content.

Note. Warmth = Mother’s warmth. Supportiveness = Mother’s supportiveness of adolescent responses to discrimination.

Acknowledgments

The National Institute of Mental Health (1R21MH083986-01A1) and the Purdue Research Foundation funded this research. This research was presented at the 2014 conference of the American Psychological Association. We would also like to thank Tony Johnson and Indy Parks & Recreation, City of Indianapolis, Indiana for assistance with data collection in the early stages of this research. We also wish to thank Elaine Anderson, Velma McBride Murry, and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this article. We would like to thank the numerous research assistants involved in this research. Lastly, we are grateful to the families who participated in this research.

Contributor Information

Mia A. Smith-Bynum, University of Maryland, College Park

Riana E. Anderson, Yale University School of Medicine

BreAnna L. Davis, University of Maryland, College Park

Marisa G. Franco, University of Maryland, College Park

Devin English, The George Washington University.

References

- Bassett MT. #BlackLivesMatter — A challenge to the medical and health communities. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372:1085–1087. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman PJ, Howard C. Race-related socialization, motivation, and academic achievement: A study of black youth in three-generation families. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1985;24:134–141. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60438-6. dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0002-7138(09)60438-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TL, Linver MR, Evans M, DeGennaro D. African-American parents’ racial and ethnic socialization and adolescent academic grades: Teasing out the role of gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:214–227. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9362-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TN, Lesane-Brown CL. Race socialization messages across historical time. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2006;69:201–213. doi: 10.1177/019027250606900205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bynum MS, Burton ET, Best C. Racism experiences and psychological functioning in African American college freshmen: Is racial socialization a buffer? Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:64–71. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caughy MO, Randolph SM, O’Campo PJ. The Africentric Home Environment Inventory: An observational measure of the racial socialization features of the home environment for African American preschool children. Journal of Black Psychology. 2002;28:37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Caughy MO, Nettles SM, Lima J. Profiles of racial socialization among African American parents: Correlates, context, and outcome. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2011;20:491–502. doi: 10.1007/s10826-010-9416-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavous TM, Rivas-Drake D, Smalls C, Griffin T, Cogburn C. Gender matters, too: The influences of school racial discrimination and racial identity on academic engagement outcomes among African American adolescents. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:637–654. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist. 1999;54:805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066X.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coard S, Pasamonte K, Smith T. Communicating about race: the Parent-child Race-related Observational Measure. Poster presentation at the American Psychological Association; Toronto, Canada. 2009. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- Coard SI, Wallace SA. The Parent-Child Race Related Observational Measure (PC-ROM) Department of Human Development and Family Studies. University of North Carolina-Greensboro; Greensboro, North Carolina: 2001. Unpublished manual. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper SM, McLoyd VC. Racial barrier socialization and the well-being of African American adolescents: The moderating role of mother–adolescent relationship quality. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:895–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duquette C, Orders S, Fullarton S, Robertson-Grewal K. Fighting for their rights: Advocacy experiences of parents of children identified with intellectual giftedness. Journal for the Education of the Gifted. 2011;34:488–512. doi: 10.1177/016235321103400306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore CA, Gaylord-Harden NK. The influence of supportive parenting and racial socialization messages on African American youth behavioral outcomes. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2012;22:63–75. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9653-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Field AP. Discovering statistics using SPSS. London, England: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Wallace SA, Fenton RE. Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29:679–695. doi: dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1026455906512. [Google Scholar]

- Frabutt JM, Walker AM, MacKinnon-Lewis C. Racial socialization messages and the quality of mother/child interactions in African American families. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2002;22:200–217. doi: 10.1177/0272431602022002004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:218–236. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JP, Lynch ME. Girls at puberty. New York: Springer; 1983. The intensification of gender-related role expectations during early adolescence; pp. 201–228. [Google Scholar]

- Holman AR. Doctoral dissertation. 2012. Gendered racial socialization in Black families: Mothers’ beliefs, approaches, and advocacy. Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3555722) [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN, Paikoff RL, Brooks-Gunn J. Handbook of parenting, Vol. 1: Children and parenting. Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1995. Parenting adolescents; pp. 91–118. [Google Scholar]

- Huff RE, Houskamp BM, Stanton M, Tavegia B. The experiences of parents of gifted African American children: A phenomenological study. Roeper Review. 2005;27:215–221. doi: 10.1080/02783190509554321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Bachman MA, Ruble DN, Fuligni AJ. Tuned in or tuned out: Parents’ and children’s interpretation of parental racial/ethnic socialization practices. In: Balter L, Tamis-LeMonda CS, editors. Child psychology: A handbook of contemporary issues. 2. New York, NY US: Psychology Press; 2006. pp. 591–610. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Chen L. The nature of parent’s race-related communications to children: A developmental perspective. In: Balter L, Tamis-LeMonda CS, editors. Child psychology: A handbook of contemporary issues. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press; 1999. pp. 467–490. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Hagelskamp C, Way N, Foust MD. The role of mothers’ and adolescents’ perceptions of ethnic-racial socialization in shaping ethnic-racial identity among early adolescent boys and girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:605–626. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9399-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DJ. The Racial Stories Task: Situational racial coping of black children. Pape presented at the meeting of the International Society for the Study of Behavioral Development; Quebec City, Quebec, Canada. 1996. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DJ. Parental characteristics, racial stress, and racial socialization processes as predictors of racial coping in middle childhood. In: Neal-Barnett AM, Contreras JM, Kerns KA, editors. Forging links: African American children clinical developmental perspectives. Portsmouth, NH: Greenwood Publishing Group; 2001. pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DJ. The ecology of children’s racial coping: Family, school, and community influences. In: Weisner TS, editor. Discovering successful pathways in children’s development: Mixed methods in the study of childhood and family life. Chicago, IL US: University of Chicago Press; 2005. pp. 87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Juang L, Soyed M. Sharing stories of discrimination with parents. Journal of Adolescence. 2014;37:303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesane-Brown CL. The Comprehensive Race Socialization Inventory. Journal of Black Studies. 2005;36:163–190. doi: 10.1177/0021934704273457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lesane-Brown CL. A review of race socialization within Black families. Developmental Review. 2006;26:400–426. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2006.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lesane-Brown CL, Brown TN, Tanner-Smith EE, Bruce MA. Negotiating boundaries and bonds: Frequency of young children’s socialization to their ethnic/racial heritage. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2010;41:457–464. doi: 10.1177/0022022109359688. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC, Kim JY, Burton LM, Davis KD, Dotterer AM, Swanson DP. Mothers’ and fathers’ racial socialization in African American families: Implications for youth. Child Development. 2006;77:1387–1402. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy MC, Richeson JA, Shelton JN, Rheinschmidt ML, Bergsieker HB. Cognitive costs of contemporary prejudice. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. 2012;16:560–571. doi: 10.1177/1368430212468170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters MF, Massey G. Mundane extreme environmental stress in family stress theories. Marriage & Family Review. 1983;6:193–218. doi: 10.1300/J002v06n01_10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers LE. Relational communication theory: An interactional family theory. In: Braithwaite DO, Baxter LA, editors. Engaging theories in family communication: Multiple perspectives. London, UK: Sage; 2006. Applie iPad Kindle version. from Amazon.com. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders Thompson VL. Socialization to race and its relationship to racial identification among African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology. 1994;20:175–188. [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Caldwell CH, Sellers RM, Jackson JS. The prevalence of perceived discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1288–1297. doi: 10.1037/a0012747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Douglass S. School diversity and racial discrimination among African-American adolescents. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2014;20:156–165. doi: 10.1037/a0035322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh G. A comparison of two indices for the intraclass correlation coefficient. Behavioral Research. 2012;44:1212–1223. doi: 10.3758/s13428-012-0188-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:420–429. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalls C. African American adolescent engagement in the classroom and beyond: The roles of mother’s racial socialization and democratic-involved parenting. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:204–213. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalls C, Cooper SM. Racial group regard, barrier socialization, and african american adolescents’ engagement: Patterns and processes by gender. Journal of Adolescence. 2012;35:887–897. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Abernethey A. African American Families Macro-Coding Manual. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester; 1998. Unpublished manual. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Abernethy A, Harris A. Adolescent–parent interactions in middle-class African American families: Longitudinal change and contextual variations. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:458–474. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.14.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Bynum M, Usher K. “Really, he had a racist teacher”: African American parent-adolescent conversations about racial discrimination. Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence; Baltimore, MD. 2004. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Bynum M, Usher KK, Callands TA, Burton ET. An observational measure of African American parent-adolescent communication about racial discrimination. Paper presented at the biennial conference of the Society for Research on Child Development; Atlanta, GA. 2005. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Bynum M. Observing racial socialization in action: A construct validity study with African American families. Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence; Chicago, IL. 2008. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Bynum MA, Lambert SF, English D, Ialongo NS. Associations between trajectories of perceived racial discrimination and psychological symptoms among African American adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 2014;26:1059–1065. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB. Black children’s race awareness, racial attitudes, and self-concept: A reinterpretation. Annual Progress in Child Psychiatry & Child Development. 1985;25:433–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1984.tb00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC, Cameron R, Herrero-Taylor T, Davis GY. Development of the Teenager Experience of Racial Socialization Scale: Correlates of race-related socialization frequency from the perspective of Black youth. Journal of Black Psychology. 2002;28:84–106. doi: 10.1177/0095798402028002002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AJ, Blackmon SKM. The Influence of the Trayvon Martin Shooting on Racial Socialization practices of African American parents. Journal of Black Psychology. 2015;41:75–89. doi: 10.1177/0095798414563610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AJ, Speight SL. Racial identity and racial socialization attitudes of African American parents. Journal of Black Psychology. 1999;25:152–170. doi: 10.1177/0095798499025002002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton MC, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Allen WR. Sociodemographic and environmental correlates of racial socialization by Black parents. Child Development. 1990;61:401–409. doi: 10.2307/1131101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trainor AA. Diverse approaches to parent advocacy during special education home–school interactions: Identification and use of cultural and social capital. Remedial and Special Education. 2010;31:34–47. doi: 10.1177/0741932508324401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Varner F, Mandara J. Discrimination concerns and expectations as explanations for gendered socialization in African American families. Child Development. 2013;84:875–890. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]