Abstract

Background

Order and amount of information influence patients’ risk perceptions, but most studies have evaluated patients’ reactions to written materials. The objective of this study was to examine the effect of four communication strategies, varying in their order and/or amount of information, on judgments related to an audible description of a new medication and among patients who varied in subjective numeracy.

Methods

We created five versions of a hypothetical scenario describing a new medication. The versions were composed to elucidate whether order and/or amount of the information describing benefits and adverse events influenced how subjects valued a new medication. After listening to a randomly assigned version, perceived medication value was measured by asking subjects to choose one of the following statements: the risks outweigh the benefits, the risks and benefits are equally balanced, or the benefits outweigh the risks.

Results

Of the 432 patients contacted, 389 participated in the study. Listening to a brief description of benefits followed by an extended description of adverse events resulted in a greater likelihood of perceiving that the medication’s benefits outweighed the risks compared to: 1) presenting the extended adverse events description before the benefits, 2) giving a greater amount of information related to benefits, and 3) sandwiching the adverse events between benefits. These associations were only observed among subjects with average or higher subjective numeracy.

Conclusion

If confirmed in future studies, our results suggest that, for patients with average or better subjective numeracy, perceived medication value is highest when a brief presentation of benefits is followed by an extended description of adverse events.

Effective communication about the potential risks and benefits of treatment is a legal and ethical imperative that is in keeping with patients’ preferences for full disclosure. Yet, patients are frequently inadequately informed about the medications they are currently taking (1). Although many concerns exist related to these communication processes, one of the most common problems faced by physicians is the sheer number of possible adverse events to disclose.

Studies have shown that decision makers are influenced by the number and type of items used to describe each option (2). For example, in a series of experiments based on the affect heuristic, Finucane et al. (3) demonstrated that varying the type of information provided about a specific technology results in predictable changes in judgments of risk and benefit: providing information describing benefits as high (with no added risk information) results in lower risk ratings; whereas, providing information describing risks as high (with no added benefit information) results in lower benefit ratings. These findings may apply to the magnitude or amount of risk and benefit information provided. Given that physicians almost always describe a larger number of adverse events than benefits, possible risks could be expected to have an inflated impact on patients’ decisions simply as a function of the amount of information presented (4). In addition, greater amounts of information can decrease the quality and effectiveness of decision making. Patients may have more difficulty understanding greater amounts of information (5) and added complexity increases the likelihood of deferring or refusing treatment (6). The influence of amount of information on patients’ judgment and choice may be especially evident among subjects with lower numeracy (the ability to understand and use probabilistic and mathematical concepts) (7-9).

The order in which information is presented may also influence subjects’ judgments. It has been well documented that subjects recall items more easily when they are presented first or last on a list compared to when they are presented in the middle (10-12). Although the literature on order effects has focused extensively on recall, studies also suggest an impact on judgment and preferences (13). The primacy effect results in subjects using the first presented piece of information more in subsequent judgments and choices, whereas the recency effect refers to the observation that people’s decisions tend to be influenced more strongly by information presented last (14). For example, consistent with a primacy effect, candidates listed first on election ballots tend to receive more votes (15, 16) and people prefer cars whose positive attributes are presented first (17). In contrast, audience members’ ratings for contestants are higher for those appearing towards the end of a performance indicative of a recency effect (18). Several factors may modify order effects. Nahari and Shakhar (19) found that respondents judge stories as more credible when reading content-rich detail first compared to last. Canic and Pachur (20) further demonstrated that primacy effects are more likely to occur with shorter sequences and in subjects with stronger preference for the status quo.

Although the majority of papers on this topic have been published outside of the medical domain, several studies related to health care have found evidence for both primacy and recency effects in students, clinicians, and online panel members (21-24). In an experimental study manipulating the order of risk and benefit information in a decision aid, women who read about the risks of a drug to prevent breast cancer last (i.e., after the benefits) had higher knowledge scores, were more worried about side effects, and judged benefits less favorably than women who received information about risks first (25), indicating a recency effect. In contrast, Bansback et al (23) found that subjects were more likely to choose options concordant with their values when presented with attributes most important to them first, consistent with a primacy effect (23).

Despite the fact that patients tend to receive information from their physicians in an spoken format, little is known about whether order effects affect patients’ judgments related to audible health-related information. Unnava et al (26) found that students’ attitudes toward a described product (book bag) were influenced by information presented at the beginning of the advertisement (i.e., consistent with a primacy effect) when delivered using audible, but not, visual information. Thus, the impact of order effects described in response to written materials may be different to audible information. A recent literature search did not uncover any experimental studies examining the impact of order or amount of spoken information in patients.

To determine best practices for describing medications associated with numerous adverse events, it is first necessary to understand the effects of alternative risk communication strategies on patients’ appraisals of proposed medications. To meet this objective, we performed a randomized experiment to examine the influence of specific strategies varying the order and amount of benefit and risk information on patients’ perceived value of a proposed new medication. We sought to approximate the setting in which patients typically hear about a new medication by: 1) recruiting patients for whom the scenario and medication were relevant, 2) using audible as opposed to written information, and 3) allowing subjects to choose from whom they would prefer to listen by selecting the picture of their preferred provider from among six options on a computer screen. In addition, we assessed the impact of specific communication strategies on a patient’s perceived medication value (PMV), a clinically meaningful dependent variable which reflects the trade-offs patients must make when evaluating new treatment options.

Because of the known influence of numeracy on risk perceptions as well as treatment preferences, we hypothesized that the effect of the risk communication strategies on PMV would vary across levels of a patient’s numeric aptitude (27, 28). We measured subjective numeracy (perceived numerical aptitude and preference for numbers) because of the resistance we have previously encountered to using objective numeracy measures (which require subjects to solve mathematical problems) in our patient population. Greater primacy effects are found among more versus less motivated individuals (i.e., individuals higher versus lower in need for cognition and those lower versus higher in need for closure (29, 30)). At the same time, higher versus lower subjective numeracy (and not objective numeracy) has been associated with greater motivation in numeric tasks. As a result, we expected that subjective numeracy would relate more than objective numeracy to the motivated use of numeric information and therefore to demonstrations of primacy effects (31).

Given studies demonstrating that the less numerate generally perceive more risk across a variety of medical and non-medical scenarios (32), we hypothesized that subjects with lower numeracy would perceive less value from a proposed new medication across risk communication strategies (H1). Because persons with lower numeracy are influenced more by changes in information presentation formats compared to those with greater aptitude, we further hypothesized that subjects with lower subjective numeracy would be more strongly influenced by amount of information and perceive even lower medication value with more information (as opposed to less information) compared to more numerate subjects (H2) (9, 32). Although H2 seems intuitively plausible when added information concerns adverse events, we suspected it to be true also for benefit information because of the more deleterious effects of greater amounts of information on the less numerate (6, 33). In addition, and as mentioned previously, evidence exists that those who are more motivated to process complex information (e.g., because they gain greater satisfaction from thinking and enjoy the process of deliberating) are more strongly influenced by initial information (i.e., primacy effects (29, 30)) than those who are less so. Motivation to process numbers, in particular, is linked with subjective numeracy (31). Thus, we further hypothesized that subjects with higher subjective numeracy would be more strongly influenced by the information received first (e.g., they would be more likely to perceive that benefits outweigh the risks when benefits are described first) compared to subjects with lower subjective numeracy (H3).

Methods

Subjects

English speaking persons with a diagnosed systemic inflammatory disease, under the care of a rheumatologist and who were taking at least one prescribed disease modifying drug, were recruited from outpatient rheumatology practices. A trained research assistant telephoned all patients who had given permission to their rheumatologist to forward their names and contact information to learn about the study. Consenting patients participated in a single face-to-face interview. Subjects were compensated $25.00 at the end of the interview.

Versions

We created five versions of a hypothetical scenario to examine the impact of four risk communication strategies: 1) changing the order in which the same adverse events and benefits are presented while holding the amount of information constant; 2) changing the amount of benefit information presented, while holding the amount of adverse event information and order constant; 3) changing the amount of adverse event information presented, while holding the amount of benefit information and order constant, and 4) presenting benefits both before and after hearing about the adverse events (i.e. sandwiching). The sandwiching strategy was included because it represents a strategy that may be used in clinical practice. Providers may introduce a treatment option by describing the benefits, followed by the adverse events. Benefits may then be reintroduced in order to end the description on a positive note.

Each version began with the same introduction, after which the content included a brief or extended amount of information describing benefits and adverse events (please see Appendix for content). The amount of information (number of words) was matched across benefits and adverse events within both the brief and extended descriptions. The brief benefits description (referred to as “benefits” throughout the manuscript) included improvements in pain, fatigue and energy level, and specified disease modifying properties. This section contained 169 words. The extended benefits description (referred to as “BENEFITS” throughout the manuscript) included 283 words and similar information with added details about pathophysiology and benefits regarding quality of sleep. The short adverse events description (referred to as “aes” throughout the manuscript) (171 words) included risk of headache, dyspepsia, infections, and theoretical risk of cancer. The extended adverse events description (referred to as “AES” throughout the manuscript) (283 words) listed the same adverse events, but with a greater amount of detail. To facilitate comparison between the brief and extended text, we have highlighted comparable sections using different formatting (see Appendix). The sandwiching strategy included the first half of the BENEFITS script followed by the AES script followed by the second half of the BENEFITS script. The order and amount of benefits and adverse events for each version of presentation is described in Table 1.

Table 1. Perceived Medication Values for Each Version.

| Version | Risks > Benefits | Risks = Benefits | Benefit > Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| benefits - AES (Version #1, n=77) |

22 (29%) | 21 (27%) | 34 (44%) |

| BENEFITS - AES (Version #2, n=77) |

22 (29%) | 38 (49%) | 17 (22%) |

| BENEFITS - aes (Version #3, n=79) |

21 (27%) | 27 (34%) | 31 (39%) |

| AES - benefits (Version #4, n=78) |

27 (35%) | 31 (40%) | 20 (26%) |

| benefits - AES - benefits (Version #5, n=78) | 29 (37%) | 28 (36%) | 21 (27%) |

Actors were audiotaped as they read each of the five scripts. In addition, because of the possible effects of treating physicians’ ethnicity and gender on patients’ risk perceptions, we asked each subject to choose from whom they would prefer to hear about a new medication by choosing one of six faces (three women and three men varying in ethnicity) of physicians displayed on a computer screen (images available upon request). Each subject was then randomly assigned to listen to one of the five versions, read by their chosen physician.

Measures

All data were collected by self-report. After listening to the description of the hypothetical new medication, PMV was measured by asking subjects to choose one of the following statements: the risks outweigh the benefits (risks > benefits), the risks and benefits are equally balanced (risks = benefits), or the benefits outweigh the risks (benefits > risks). This variable was chosen as the focus of the study because it reflects an important trade-off that patients face when considering new treatment options. We also collected data on patient demographic and clinical characteristics. Subjective numeracy was measured using the 8-item Subjective Numeracy Scale (34).

Analyses

To address the first strategy (changing the order in which the same adverse events and benefits are presented while holding the amount of information constant), we compared PMV response for those who listened to Versions #4 versus #1. To address the second (changing the amount of benefit information presented, while holding the amount of adverse event information and order constant), we compared Versions #2 versus #1. We examined the third strategy (changing the amount of adverse event information presented, while holding the amount of benefit information and order constant) by comparing Versions #3 versus #2. Lastly, we compared Version #5 versus Version #1 to examine the fourth strategy (presenting benefits both before and after hearing about the adverse events, i.e., sandwiching). These comparisons are listed in Table 1.

PMV, an ordinal measure, was modeled using proportional-odds logistic regression (35). The risks > benefits category was chosen to be the referent level. The model contained main effect terms for the subject’s chosen physician (to adjust for potential confounding effects), randomly assigned version, and subjective numeracy. A version-by-subjective numeracy interaction term was included to examine whether subjective numeracy modified the effect of the specified communication strategy on PMV. The 8-item subjective numeracy scale scores were standardized (mean=0 and SD=1) so that model coefficients for the physician and version terms could be interpreted as effects for a subject at the study-specific subjective numeracy mean, and a difference of 1 unit for standardized subjective numeracy would correspond to a study specific 1-SD subjective-numeracy difference. Model fitting and analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). This study was approved by the Yale Human Research Protection Program.

Results

Of the 432 patients contacted, 395 agreed to participate in the study. Of these, two were excluded because of a hearing impairment, one was excluded because of a language barrier, and three were excluded because of a computer malfunction. The mean (SD) age of the study sample (N= 389) was 55 (14), 75% were female, 76% identified themselves as being Caucasian, 22% as African American, 2% as Asian or Pacific Islander, and less than 1% as American Indian or Alaska Native. Eighteen percent identified themselves as being of Hispanic ethnicity. Thirty-nine percent were employed and 33% reported having very good or excellent health. The three most commonly reported systemic inflammatory diagnoses were rheumatoid arthritis (53%), systemic lupus (20%) and psoriatic arthritis (16%). The majority of subjects (82%) were currently taking an immunosuppressive medication. The mean (SD) subjective numeracy score, prior to standardization, was 30.6 (9.8) (maximum possible score = 48).

Table 1 shows the distribution of PMV responses for each version. The association between PMV and version, adjusted for physician choice, was statistically significant (Model 1, Table 2). Subjective numeracy (standardized) and the version-by-subjective-numeracy interaction term were both significantly associated with PMV (Models 1 and 2, respectively, Table 2).

Table 2. Significance of Associations for Version and Subjective Numeracy with Ordinal PMV.

| Model # | Effect | c* | Wald χ2 | df | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-a | Version | 0.562 | 8.22 | 4 | 0.08 |

| 0-b | Version | 0.616 | 9.43 | 4 | 0.05 |

| Chosen physician | 17.05 | 4 | 0.002 | ||

| 0-c | Subjective numeracy | 0.611 | 20.99 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| 1 | Version | 0.657 | 10.67 | 4 | 0.03 |

| Subjective numeracy | 20.94 | 1 | <0.0001 | ||

| Chosen physician | 15.43 | 4 | 0.004 | ||

| 2 | Version | 0.676 | 11.50 | 4 | 0.02 |

| Subjective numeracy | 19.01 | 1 | <0.0001 | ||

| Subjective numeracy*version | 13.16 | 4 | 0.01 | ||

| Chosen physician | 13.81 | 4 | 0.01 |

Models for 3-level ordinal outcome PMV are proportional-odds logit models. The “risks > benefits” category is the PMV reference level. Model 1: The main effect terms in the model are subject’s chosen physician (to control potential confounding effects), randomly assigned version, and subjective numeracy. Subjective numeracy as a continuous variable was associated with PMV (OR (95% CI) for Model 0-c = 0.64 (0.53, 0.78) and for Model 1 = 0.63 (0.52, 0.77). Model 2: A version-by-subjective numeracy interaction term was included to examine whether subjective numeracy modified the effect of the specified communication strategy on PMV.

c is the ‘concordance index’, a measure of association of predicted probabilities and observed responses, calculated as the area under the ROC curve.

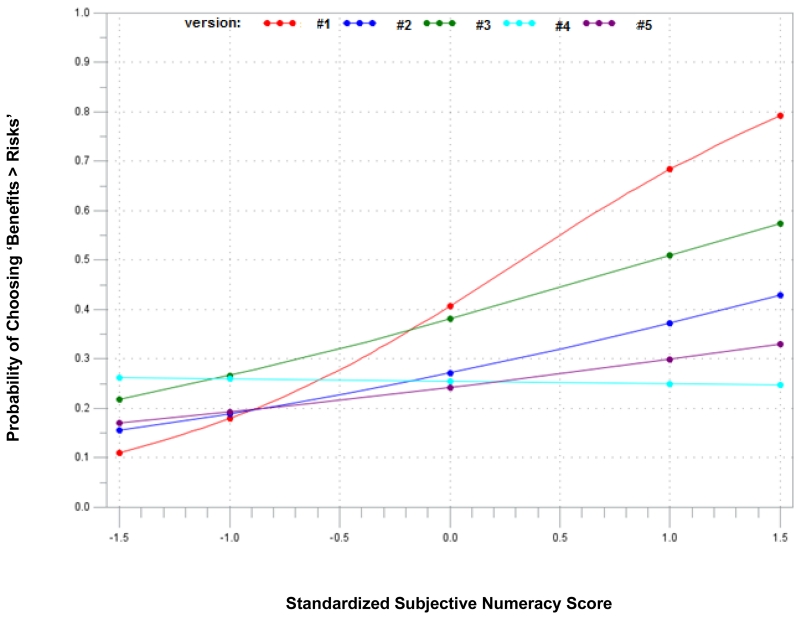

Figure 1 illustrates the modeled probability of choosing benefits > risks for each version versus some chosen levels of standardized subjective numeracy. With the exception of the AES-benefits version (#4), as subjective numeracy increases, the probability of perceiving that benefits outweigh risks also increases. These results support our first hypothesis (H1) that subjects with lower subjective numeracy would perceive less value from a proposed new medication than those with higher subjective numeracy.

Figure 1. Model-based Probability of Choosing ‘Benefits > Risks” versus Standardized Subjective Numeracy Score by Scenario.

Version=vs

Vs#1: benefits - AES

Vs#2: BENEFITS - AES

Vs#3: BENEFITS - aes

Vs#4: AES - benefits

Vs#5: benefits - AES – benefits

The associations between the strategies examined and PMV are presented in Table 3. Order had a significant influence on PMV with subjects listening to benefits before adverse events being more likely to choose benefits > risks compared to those hearing the adverse events first. This effect was only statistically significant among subjects with subjective numeracy scores at or above the study-specific mean and supports our third hypothesis (H3) that subjects with higher subjective numeracy would be more strongly influenced by the information received first.

Table 3. Associations between Risk Communication Strategies with PMV by Standardized Subjective Numeracy Scores.

| Strategy | Version Comparison | Crude / Adjusted* Odds Ratio** (95% CI) |

Crude / Adjusted OR by Standardized Subjective Numeracy Scores |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1.5 | −1.0 | 0 | 1.0 | 1.5 | |||

| Order | benefits-AES (sc #1) vs AE-benefits (sc #4) |

2.01 (1.10, 3.69) / 2.18 (1.18, 4.04) |

0.35 / 0.40 |

0.62 / 0.70 |

2.01 / 2.18 |

6.50 / 6.81 |

11.69 / 12.02 |

| Amount | |||||||

| • Benefits | benefits-AES (sc #1) vs BENEFITS-AES (sc #2) |

1.84 (1.00, 3.40) / 1.87 (1.00, 3.49) |

0.67 / 0.73 |

0.93 / 1.00 |

1.84 / 1.87 |

3.64 / 3.48 |

5.11 / 4.75 |

| • Adverse events | BENEFITS-AES (sc #2) vs BENEFITS-aes (sc #3) |

0.61 (0.34,1.09) / 0.58 (1.05, 0.32) |

0.66 / 0.66 |

0.64 / 0.63 |

0.61 / 0.58 |

0.57 / 0.53 |

0.56 / 0.51 |

| Sandwich | benefits-AES (sc #1) vs benefits-AES- benefits (sc #5) |

2.15 (1.17, 3.97) / 2.07 (1.11, 3.85) |

0.60 / 0.68 |

0.91 / 0.99 |

2.15 / 2.07 |

5.06 / 4.36 |

7.77 / 6.33 |

Adjusted for choice of physician

Proportional odds of perceiving higher benefit versus lower benefit; odds ratios greater than 1 indicate that subjects were more likely to indicate benefits>risks for the first than for the second scenario listed. Bold results indicate that 95% CI does not capture 1.00

Our second hypothesis (H2), that those lower in subjective numeracy would perceive even lower PMV with more information as opposed to less information, was not supported as amount of information had little effect on these individuals. Instead, more subjectively numerate subjects who heard less benefit information were more likely to perceive that benefits outweighed the risks compared to those hearing more information about benefits. The sandwiching strategy was also associated with a lower likelihood of choosing benefits > risks among subjects with subjective numeracy scores at or above the mean. Varying the amount of adverse events had no significant effect on PMV.

Discussion

In clinical practice, fear of drug toxicity is a frequent barrier to optimizing clinical outcomes in patients with chronic disease. Thus, it is important to understand how the strategies used by physicians to describe a suggested new medication influence patients’ judgment of the potential impact of treatment on both their short and long-term health. In this study, we found that presenting adverse event information before benefits (compared to benefits before adverse events) lowers the likelihood that subjects will perceive that the benefits outweigh the risks of a proposed new medication. This finding is consistent with the primacy effect, and suggests that ending on a positive note does not override the negative perceptions induced by beginning with a description of adverse events.

We also found that sandwiching adverse events between benefits and presenting a greater amount of information on benefits leads to a lower likelihood of choosing that benefits outweigh risks. These latter results are not consistent with the affect heuristic which predicts that a greater amount of information related to benefits will result in more positive evaluations (36), but are consistent with prior research demonstrating that decision makers seem to average attributes so that adding a good attribute (but less good than the others) can reduce the appeal of a choice option. For example, Hsee (33) found that subjects were willing to pay more for a set of dinner ware items (plates and bowls) in good condition compared to subjects evaluating a set with the same items plus additional cups and saucers of which some were in good condition and others were broken.

The less-is-more effect, i.e., potential deleterious effects of greater amounts of information, has been well documented in the literature. Less information can lead to greater comprehension and use of the material presented (5) and added complexity increases the likelihood of deferral (6). We had predicted that a less-is-more effect would occur to a greater extent in subjects with low numeracy, but found the opposite. The lack of effect of order and/or amount of information observed among the less numerate in this study suggests that patterns viewed primarily in studies utilizing written materials may not be generalizable to audible formats.

The main difference between the extended and brief benefit descriptions was the addition of improved sleep quality in the former. It is possible that specific types of benefits may have differential effects. For instance, patients may attend more to benefits that are important to them and become distracted by those that are not. If the participants in this study did not value improvement in sleep quality, the added information may have lowered their impressions of benefits. If true, these results would be consistent with studies that have found decision makers to be influenced by the number of attributes favoring each of their choice options (36). It is also possible that patients are most familiar with hearing relatively little detail about benefits and a longer list of potential adverse events when being told about new immunosuppressive medications, and that presenting them with unexpected detail may unintentionally lower their perceived benefit of the medication.

Varying the amount of adverse event information had no significant effect on PMV. However, a smaller proportion of participants stated that benefits outweigh risks in Version 2 with more extended AEs as compared to Version 3 with a briefer AE description. Given this trend, and the less-is more effect described in the preceding paragraph, it would be important in future studies to examine additional manipulations varying the amount of specific types of benefits and adverse events on patients’ judgments of risks and benefits.

The other notable finding in this study was that the effects of order and/or amount of information on PMV were observed only among subjects having average or higher than average subjective numeracy scores. Thus, our results do not inform methods to decrease risk aversion among those with lower subjective numeracy, which is unfortunate since these are the patients most likely to benefit from an improved understanding of the benefit to risk ratio of proposed new medications. These results are consistent with the literature demonstrating that subjects with lower numeracy are more strongly influenced by factors extraneous to the information presented (such as affect) (37), as well as prior research demonstrating that the influence of initial information is stronger among those with greater motivation to process complex information (29, 30). To the best of our knowledge, however, this is the first study involving patients to document the effect of subjective numeracy on primacy effects in a medical domain, and in response to audible information.

In keeping with studies demonstrating that persons with lower numeracy tend to be more risk averse (7, 8, 38), subjects with higher subjective numeracy were also more likely to judge the medication as having benefits that outweigh the risks compared to subjects with lower subjective numeracy across all versions, except when adverse events were presented first.

There are several important strengths to this study. To better represent risk communication in clinical practice, we assessed patients’ judgments after listening to information. This is in contrast to the majority of studies in which risk perceptions are measured in response to written materials. We also enabled patients to “choose” their preferred physician given the possible influence of physician gender and ethnicity on patients’ judgments. Lastly, the dependent variable PMV forces a trade-off between risks and benefits and thus more closely resembles the judgments that patients make compared to rating scales measuring perceived risk and benefit separately.

Limitations of the study include the use of a hypothetical scenario, which although it enabled us to use an experimental design, cannot exactly replicate communication between patients and their physicians. The study was performed in a single population and further research is required to study the effects of order and amount of risk benefit information in other populations and in other medical contexts. Because of the sample size required for a full design, we did not include all possible order and amount of information comparisons. As a result, we did not include a strategy with brief benefits followed by brief adverse events. The amount of adverse events presented after extended benefits did not influence PMV, thus we suspect that the amount of adverse events presented will not matter, but this speculation deserves further testing. It is possible that the amount of additional detail presented in the extended description of adverse events was not large enough to effectively test differences between amounts of information. Our manipulation included differences in both the amount and type of information included in the brief and extended descriptions of both benefits and adverse events. For example, in the extended benefits description fatigue is described as “patients feel less fatigued” and in the brief description as patients have “very little fatigue”. In the preceding example, relative terms are used in the extended description while absolute terms are used in the brief version. Although subtle, these differences may also have contributed to the differences found. In addition, studies have found that the richness in content can influence order effects, even after controlling for the length of the descriptions presented (19). Thus, although the text has high face validity in terms of the type of information actually communicated to patients, future research is needed to disentangle the effects of each of these factors on risk perceptions. Order effects are believed to be mediated partially by working memory (10). However, several studies have demonstrated that order can influence how information is evaluated and how preferences are constructed (16, 18, 23, 25, 39). Dependent variables in these studies have included subjects’ ratings as well as choices. We evaluated the impact of amount of information and order effects on patients’ evaluations of a proposed medication. Recall was not assessed and future studies are needed to determine whether the order effect observed in this study was mediated by differences in recall of specific risk- and/or benefit-related knowledge.

In summary, this study confirms previous findings that subjects with average or higher subjective numeracy are more likely to have favorable judgments related to new medications and suggests that the order and amount of audible information presented may influence the PMV among this subgroup of patients (order and amount of information had little effects on those lower in subjective numeracy). It also raises questions about what strategies could be used to mitigate risk aversion among less numerate and more skeptical patients. Compared to presenting a brief description of benefits followed by a more extended description of AEs (arguably the most used format in actual clinical practice), presenting adverse events first lowered the probability of perceiving that the benefits outweigh the risks. The assumption that a greater amount of information describing benefits would increase PMV was not supported in this study. If these results are replicated, they would support specific recommendations for communication of risk-benefit information, at least among those higher in subjective numeracy.

Acknowledgments

This clinical research study was made possible by a grant from the Arthritis Foundation. Research reported in this publication was also supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health, under Award Number AR060231-01 (Fraenkel). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Peters is supported by National Science Foundation Grants SES-1047757 and 1155924. The authors do not have any financial interests that would be considered a conflict of interest. Each of the co-authors listed has had a substantial role in the creation of this manuscript and the work reported herein.

Appendix

Each version started with the same introduction:

Hello, my name is Dr - and I know we have never met before – but for the next few minutes – try and pretend that I am your regular doctor. In this video I am going to be telling you about a new medication. Ok let’s start:

There is a medication that I would like to recommend for you. Before we get into details, it is important that you know that the medication is completely covered by your insurance. It is a small pill taken once a day and it does not interfere with any of your other medications. This medication works by targeting specific cells of the immune system that in your case are overactive and cause inflammation. It tends to start working quickly, so you may feel the benefits within 2 to 4 weeks. So let’s talk about the benefits of this medication:

To facilitate comparisons, comparable content are presented in the same font across brief and extended benefits. The description of sleep is unique to the extended benefits scenario (ALL CAPITALIZED). The same applies to the brief and extended adverse event descriptions.

Brief Benefits

First, it is very effective for relieving pain and fatigue. About half (or 50%) of the people taking this medication have mild to moderate pain every now and then and very little fatigue. And about one quarter (or 25%) will improve to the point where they are almost completely pain free and have as much energy as they did before they got sick. Because patients taking this medication have less pain and fatigue, they are able to be more active, work (either in or outside of the home) with less difficulty, and participate in more social and recreational activities outside of the house. What is really important is that this medication doesn’t just treat your symptoms. It is aimed at targeting the actual cause of your illness, and so it decreases the chance of flare ups and the progression of your disease. Because the medication controls the underlying disease it also decreases your risk of future complications that are caused by years of inflammation such as heart attacks.

Extended Benefits

First, it is very effective for relieving pain. About half (or 50%) of the people taking this medication will have their pain reduced to the point where they only have mild to moderate pain every now and then which doesn’t prevent them from doing the activities they want to do. And about one quarter (or 25%) of people will improve to the point where they are almost completely pain free. THIS MEDICATION CAN ALSO IMPROVE THE QUALITY OF YOUR SLEEP. THIS IS IMPORTANT BECAUSE PATIENTS WITH YOUR ILLNESS OFTEN HAVE TROUBLE SLEEPING. AND THEY HAVE DISRUPTED SLEEP PATTERNS WHEN MEASURED IN A SPECIALIZED SLEEP LABORATORY. MANY PATIENTS, EVEN THOSE WHO SLEEP WELL – OFTEN FEEL VERY FATIGUED OR TIRED. THE FATIGUE IS CAUSED BY AN INCREASED LEVEL OF SPECIFIC CHEMICALS IN YOUR BLOOD. THE MEDICATION DECREASES THE LEVELS OF THESE CHEMICALS AND THAT’S WHY PATIENTS FEEL LESS FATIGUED AND MORE ENERGETIC. Because patients feel better, they are able to be more active, work with less difficulty, (regardless of whether you work at home or outside of the home) and have an easier time enjoying social, leisure, and recreational activities outside of the house. What is really important is that this medication doesn’t just treat your symptoms. It is aimed at targeting the actual cause of your illness, and so it decreases the chance of flare ups and it decreases the progression of your disease. Controlling the underlying disease also decreases your risk of future complications. Patients who have illnesses that cause inflammation are at higher risk for heart disease. Taking this medication and controlling inflammation now, may lower your risk of having a heart attack in the future.

Brief Adverse Events

The medication is very well tolerated in almost all patients who take it – but there are some side effects that you need to be aware of. About 10% of people taking the medication have some stomach discomfort or headaches from the medication. Patients taking this medication are at increased risk of infections such as bronchitis. Bronchitis happens in about 10% to 15% of patients and can be easily treated with antibiotics. Pneumonia which happens more rarely – in about 3% of people – needs to be treated in the hospital with intravenous antibiotics. Sepsis is a very serious condition that can decrease blood flow to your heart, lungs and kidneys. It happens in about 1 in 1000 people taking this medication. Sepsis is always treated in the intensive care unit and can rarely be life threatening. When this medication came on the market doctors worried that it might weaken the immune system’s ability to recognize early cancer cells. While we are still not certain whether or not these drugs increase the risk of cancer, large studies have not shown any significant increased risk in adults taking this medication compared to adults taking other medications.

Extended Adverse Events

The medication is very well tolerated in almost all patients who take it – but there are some side effects that you need to be aware of. About 10% of people taking the medication have some stomach upset or a queasy feeling that comes and goes. About the same number of patients, about 10%, develop a headache and some dizziness or lightheadedness from the medication. If needed the headaches can be treated with Tylenol. Patients taking this medication are at increased risk of infections. About 10 to 15% of patients develop bronchitis. This is when you feel like you have a cold and have a cough and you may have a fever. This type of bronchitis gets better in about a week with antibiotics that you take by mouth. About 3% of people develop pneumonia that needs to be treated in a hospital with intravenous (or IV) antibiotics for about a week. People who have had pneumonia say that it takes a good 3 weeks to start feeling like yourself again. About 1 in 1,000 people develop a serious infection called “sepsis”. Sepsis can decrease blood flow to the kidneys, liver, and lungs and is always treated in the intensive care unit with intravenous (or IV) medications. In rare cases, sepsis can be life threatening. When this medication came on the market, doctors worried that it might increase the risk of cancer. One of the jobs of the immune system is to find early cancer cells and destroy them. Doctors worried that this medication might weaken the immune system’s ability to recognize these early cancer cells. While we are still not certain whether or not this medication increases the risk of cancer, several large studies done over the past 10 years, have not shown any increased risk of cancer in adults taking this medication.

References

- 1.Katz JN, Daltroy LH, Brennan TA, Liang MH. Informed consent and the prescription of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:1257–63. doi: 10.1002/art.1780351103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janis IL, Mann L. Decision-making. A psychological analysis of conflict, choice, and committment. The Free Press; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finucane M, Alhakami A, Slovic P, Johnson SM. The affect heuristic in judgments of risks and benefits. J Behav Dec Making. 2000;13:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Payne JP, Bettman JR, Johnson EJ. Contingencies in decision making. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters E, Dieckmann N, Dixon A, Hibbard JH, Mertz CK. Less is more in presenting quality information to consumers. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64:169–90. doi: 10.1177/10775587070640020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhar R. The effect of decision strategy on deciding to defer choice. J Behav Dec Making. 1996;9:265–81. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters E, Hibbard J, Slovic P, Dieckmann N. Numeracy skill and the communication, comprehension, and use of risk-benefit information. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:741–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reyna VF, Nelson WL, Han PK, Dieckmann NF. How numeracy influences risk comprehension and medical decision making. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:943–73. doi: 10.1037/a0017327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Angott AM, Ubel PA. The benefits of discussing adjuvant therapies one at a time instead of all at once. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;129:79–87. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1193-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li C. Primacy effect or recency effect? A long-term memory test of Super Bowl commercials. J Cons Behav. 2010;9:32–44. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Postman L, Phillips LW. Short-term temporal changes in free recall. Quart J Exp Psychol. 1965;17:132–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart DD, Stewart CB, Tyson C, Vinci G, Fioti T. Serial position effects and the picture-superiority effect in the group recall of unshared information. Group Dyn-Theory Res. 2004;8:166–81. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hogarth RM, Einhorn HJ. Order effects in belief updating: The belief-adjustment model. Cogn Psychol. 1992;24:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lichtenstein M, Srull TK. Conceptual and methodological issues in examining the relationship between consumer memory and judgment. In: Alwitt LF, Mitchell AA, editors. Psychological processes and advertising effects: Theory, research, and application. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1985. pp. 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen E, Simonovits G, Krosnick JA, Pasek J. The impact of candidate name order on election outcomes in North Dakota. Electoral Studies. 2014;35:115–22. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller JM, Krosnick JA. The impact of candidate name order on election outcomes. Public Opin Quart. 1998;62:291–330. [Google Scholar]

- 17.González Vallejo C, Cheng J, Phillips N, et al. Early positive information impacts final evaluations: No deliberation-without-attention effect and a test of a dynamic judgment model. J Behav Dec Making. 2014;27:209–25. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruine de Bruin W. Save the last dance for me: Unwanted serial position effects in jury evaluations. Acta Psychologica. 2005;118:245–60. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nahari G, Ben-Shakhar G. Primacy effect in credibility judgements: The vulnerability of verbal cues to biased interpretations. Applied Cogn Psychol. 2013;27:247–55. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canic E, Pachur T. Serial-position effects in preference construction: A sensitivity analysis of the pairwise-competition model. Front Psychol. 2014;5 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chapman GB, Bergus GR, Elstein AS. Order of information affects clinical judgment. J Behav Dec Making. 1996;9:201–11. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curley SP, Young MJ, Kingry MJ, Yates JF. Primacy effects in clinical judgments of contingency. Med Decis Making. 1988;8:216–22. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8800800310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bansback N, Li LC, Lynd L, Bryan S. Exploiting order effects to improve the quality of decisions. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kostopoulou O, Russo JE, Keenan G, Delaney BC, Douiri A. Information distortion in physicians’ diagnostic judgments. Med Decis Making. 2012;32:831–9. doi: 10.1177/0272989X12447241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ubel PA, Smith DM, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, et al. Testing whether decision aids introduce cognitive biases: Results of a randomized trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80:158–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Unnava HR, Burnkrant RE, Erevelles S. Effects of presentation order and communication modality on recall and attitude. J Consumer Res. 1994;21:481–90. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fraenkel L, Cunningham M, Peters E. Subjective numeracy and preference to stay with the status quo. Med Decis Making. 2015;35:6–11. doi: 10.1177/0272989X14532531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peters E, Västfjäll D, Slovic P, Mertz CK, Mazzocco K, Dickert S. Numeracy and decision making. Psychol Sci. 2006;17:407–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cacioppo JT, Petty RE, Feinstein JA, Blair W, Jarvis G. Dispositional differences in cognitive motivation: The life and times of individuals varying in need for cognition. Psychol Bull. 1996;119:197–253. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kruglanski AW, Webster DM. Motivated closing of the mind: “Seizing” and “freezing”. Psychol Rev. 1996;103:263–83. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.103.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peters E, Bjalkebring P. Multiple numeric competencies: When a number is not just a number. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015;108:802–22. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peters E. Beyond comprehension: The role of numeracy in judgments and decisions. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2012;21:31–5. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsee CK. Less is better: When low-value options are valued more highly than high-value options. J Behav Dec Making. 1998;11:107–21. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fagerlin A, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Ubel PA, Jankovic A, Derry HA, Smith DM. Measuring numeracy without a math test: Development of the Subjective Numeracy Scale (SNS) Med Decis Making. 2007;27:672–80. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07304449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agresti A. 2 ed. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2010. Analysis of Ordinal Categorical Data. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hibbard JH, Slovic P, Peters E, Finucane ML. Strategies for reporting health plan performance information to consumers: Evidence from controlled studies. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:291–313. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peters E, Dieckmann NF, Vastfjall D, Mertz CK, Slovic P, Hibbard JH. Bringing meaning to numbers: The impact of evaluative categories on decisions. J Exp Psychol Appl. 2009;15:213–27. doi: 10.1037/a0016978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pachur T, Galesic M. Strategy selection in risky choice: The impact of numeracy, affect, and cross-cultural differences. J Behav Dec Making. 2013;26:260–71. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mantonakis A, Rodero P, Lesschaeve I, Hastie R. Order in choice: Effects of serial position on preferences. Psychol Sci. 2009;20:1309–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]