Highlights

-

•

Cerebellar herniation following a craniectomy to the posterior fossa is a rare complication.

-

•

Surgery was necessary to push the cerebellum back inside and plastic surgery to the bone was carried out.

-

•

Possible causes were discussed.

Keywords: Craniectomy, Posterior fossa, Cerebellar herniation, Neurosurgical complication, Case report

Abstract

This article presents a very rare late complication of surgery to the posterior fossa involving a craniectomy: cerebellar hemisphere herniation in the neck, through the craniectomy site. Here we also analyse the possible causes of such complication.

1. Introduction

In this article we report a case, which we had never encountered before, of a late complication relative to a posterior fossa craniectomy.

Having searched the main scientific databases (ISI Web, Scopus and Google scholar) we did not come across another report of this kind written in the last 20 years.

1.1. Presentation

A 40-year-old woman underwent a right side suboccipital craniectomy to remove in-toto a cerebellar angioblastoma (Fig. 1). As is often the case in this kind of surgery, the dura mater shrunk somewhat and could only be partially stretched out and stitched back up, so in order to close the remaining gap, a self-adhesive artificial substitute patch was used, which was made of synthetic and resorbable biomaterial. The Patient was discharged from hospital five days after surgery in great general health, without any neurological impairments; she had also undergone a post-operative CT scan that showed no oedema or haemorrhage in the site of surgery, nor the presence of any other type of problem. She had a check-up a week after being discharged and the stitches were removed. The wound had closed and her neurological conditions were excellent.

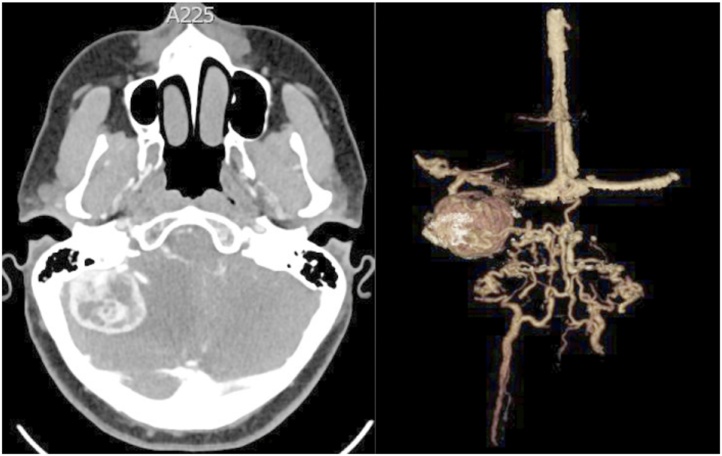

Fig. 1.

image of the angioblastoma before removal with the first surgery, which comprised the craniectomy procedure.

However, 4 weeks later, the patient was rushed to our hospital because, for the preceding 4 days, she had been suffering from pain in the nape of the neck, ataxia when walking, dysmetria of the right arm and paraesthesia of the right side of her face. Symptoms had appeared a few hours after the Patient, feeling well, had for the first time since the operation gone to the gym. In hospital an MRI scan was carried out and it showed a right cerebellar hemisphere herniation in the neck, which had come through the site of the craniectomy (Fig. 2). The patient was operated again to reduce the herniation. The former wound was reopened, the area of the parenchymal herniation and craniectomy was exposed: the bulging cerebellar parenchyma was covered by a very thin membrane, which was probably the very stretched synthetic dura mater substitute patch (which we have described before).

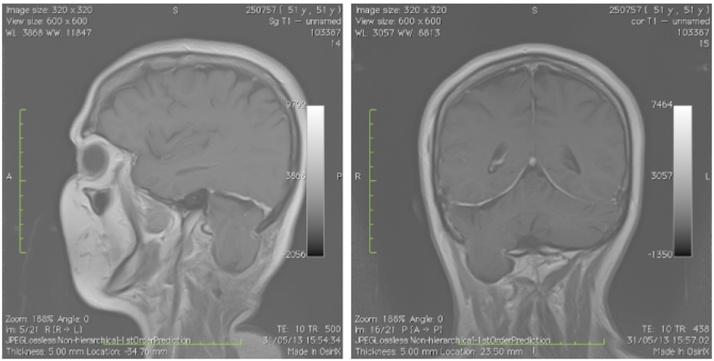

Fig. 2.

The MRI shows a large herniation of the right cerebellar hemisphere in the neck through the site of the craniectomy.

It was deemed necessary to widen by a small degree the area of cranium removed; then, without removing the aforementioned membrane, the chief surgeon with the palms of his hands placed a gentle but steady pressure on the bulging part of the cerebellum thus managing to slowly push it back into the posterior fossa of the cranium. A titanium plate was immediately used to replace the missing area of the cranium and fibrin glue was applied outside the plate to add volume. Barely a few hours after surgery, symptoms disappeared entirely. The MRI carried out the day after the new surgery confirmed the complete resolution of the herniation (Fig. 3). Subsequent MRI scans and clinical check-ups in the following months showed no abnormalities.

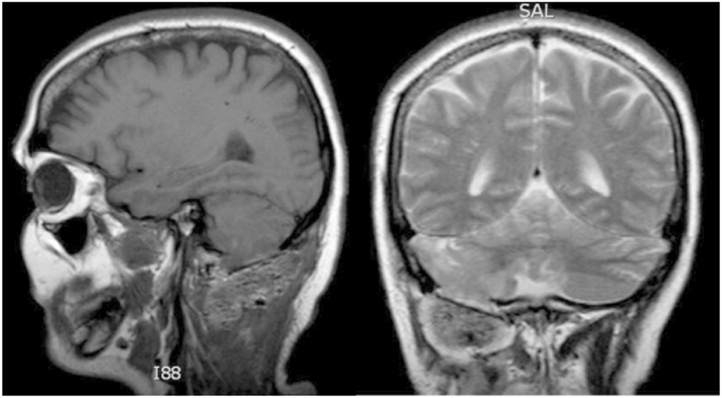

Fig. 3.

The MRI after the plastic surgery to the cranium shows the resolution of the herniation.

2. Discussion

Posterior fossa surgery traditionally implies use of a craniectomy, in other words: permanent bone removal, without any type of bone replacement; in the last few years however a growing number of surgeons prefer a craniotomy to a craniectomy even in the posterior fossa [1], [2], [3] .The most frequent complications of a craniectomy are pseudomeningoceles, CSF leaks and infections; in the Literature we were not able to find a case like ours of parenchyma herniation through the missing bone flap in the last 20 years.

We believe this complication to have been caused by a number of factors. There is a high probability that the physical training at the gym might have caused a marked increase in intracranial pressure, which in all likelihood triggered the herniation process. It is moreover possible that during the first operation the process of sealing the muscular layers might not have been carried out with the right amount of care and focus; in particular, the muscles that had been cut might not have been stitched back up with the right amount of tension so as to give appropriate support to the parenchyma below. The synthetic dura mater substitute patch certainly proved great at containing and in fact avoiding any liquor leaks, but it was wholly ineffective as a supporting structure for the parenchyma.

3. Conclusion

This extremely rare complication of a craniectomy of the posterior fossa confirms an already well known fact, that closing the operatory field is as important as all the other stages of a surgery and any type of inaccuracy in closing the opening created during the operation can have dire consequences for the overall result of the operation, this case furthermore proves that complications can occur even a long time after surgery when the body is put under physically stressful conditions.

Contributor Information

Riccardo Caruso, Email: riccardo.caruso@uniroma1.it.

Alessandro Pesce, Email: ale_pesce83@yahoo.it.

Emanuele Piccione, Email: epiccione@sirm.org.

Luigi Marrocco, Email: lumarrocco@gmail.com.

Venceslao Wierzbicki, Email: wenzel@alice.it.

References

- 1.Dubey A., Sung W.S., Shaya M., Patwardhan R., Willis B., Smith D., Nanda A. Complications of posterior cranial fossa surgery—an institutional experience of 500 patients. World Neurosurg. 2009;72(4):369–375. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hadanny A., Rozovski U., Nossek E., Shapira Y., Strauss I., Kanner A.A., Sitt R., Ram Z., Shahar T. Craniectomy versus craniotomy for posterior fossa metastases: complication profile. World Neurosurg. 2016;89(May):193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.01.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Legnani F.G., Saladino A., Casali C., Vetrano I.G., Varisco M., Mattei L., Prada F., Perin A., Mangraviti A., Solero C.L. Craniotomy vs. craniectomy for posterior fossa tumors: a prospective study to evaluate complications after surgery. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 2013;155(December (12)):2281–2286. doi: 10.1007/s00701-013-1882-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]