Abstract

Understanding the social evolution leading to insect eusociality requires, among other, a detailed insight into endocrine regulatory mechanisms that have been co-opted from solitary ancestors to play new roles in the complex life histories of eusocial species. Bumblebees represent well-suited models of a relatively primitive social organization standing on the mid-way to highly advanced eusociality and their queens undergo both, a solitary and a social phase, separated by winter diapause. In the present paper, we characterize the gene expression levels of major endocrine regulatory pathways across tissues, sexes, and life-stages of the buff-tailed bumblebee, Bombus terrestris, with special emphasis on critical stages of the queen's transition from solitary to social life. We focused on fundamental genes of three pathways: (1) Forkhead box protein O and insulin/insulin-like signaling, (2) Juvenile hormone (JH) signaling, and (3) Adipokinetic hormone signaling. Virgin queens were distinguished by higher expression of forkhead box protein O and downregulated insulin-like peptides and JH signaling, indicated by low expression of methyl farnesoate epoxidase (MFE) and transcription factor Krüppel homolog 1 (Kr-h1). Diapausing queens showed the expected downregulation of JH signaling in terms of low MFE and vitellogenin (Vg) expressions, but an unexpectedly high expression of Kr-h1. By contrast, reproducing queens revealed an upregulation of MFE and Vg together with insulin signaling. Surprisingly, the insulin growth factor 1 (IGF-1) turned out to be a queen-specific hormone. Workers exhibited an expression pattern of MFE and Vg similar to that of reproducing queens. Males were characterized by high Kr-h1 expression and low Vg level. The tissue comparison unveiled an unexpected resemblance between the fat body and hypopharyngeal glands across all investigated genes, sexes, and life stages.

Keywords: social insects, social evolution, diapause, reproduction, caste differentiation, hormones, endocrine glands

Introduction

The evolution of cooperation, altruism and eusociality is one of the outstanding problems in science (Pennisi, 2005). A huge body of work has been dedicated to the theoretical foundations of eusociality, starting with the classical works of Hamilton (1963). In recent years, genomic studies have helped to address more proximate questions of social evolution (e.g., Toth et al., 2007; Simola et al., 2013; Woodard et al., 2014; Kapheim et al., 2015). However, relatively little is known about the physiology underlying the transitions from the solitary to social life style (Robinson et al., 2005; Woodard et al., 2011), and studies on highly eusocial insects are in some respect of limited value because they represent a highly derived state. In contrast, bumblebees are suitable models in this respect due to their relatively primitive social organization (Amsalem et al., 2015a; Sadd et al., 2015). Within their short lifespan, delimited by the annual life cycle of the colonies in temperate climates, bumblebee queens undergo several dramatic shifts in life style and physiology, starting with a solitary pre-hibernation phase, through solitary diapause and nest founding to the social and reproductive phase as mother queens (e.g., Goulson, 2010). In insects, such transitions are accompanied by significant, hormonally regulated changes in fertility and metabolism (Arrese and Soulages, 2010). Juvenile hormone (JH) is the major regulator of insect development and reproduction (e.g., Riddiford, 2012; Jindra et al., 2013). The metabolism is controlled by two types of neuropeptides and their signaling pathways (Antonova et al., 2012). The first group belongs to the functional homologs of the vertebrate insulin. Insulin-like peptides and insulin/insulin-like growth factors (ILPs/IGFs) make up together a complex signaling network (IIS), which is tightly interconnected with JH signaling (reviewed in e.g., Antonova et al., 2012; Badisco et al., 2013). The second group comprises functionally well described energy mobilizing factors of the adipokinetic hormone family (AKHs), functionally equivalent to the mammalian glucagon (Kim and Rulifson, 2004). Relatively little is known on the integration of these signaling pathways in bumblebees, and especially in the dynamically changing physiology of bumblebee queens, when compared to some models of solitary insects or the socially highly derived European honey bee, Apis mellifera.

We selected the methyl farnesoate epoxidase gene (MFE) as an indicator of JH production, since the expression levels of this gene, coding for the enzyme that catalyzes the final step of JH III biosynthesis, are known to be correlated with JH titers, e.g., in honeybee workers (Bomtorin et al., 2014). MFE was also identified in a number of other insect species (Daimon and Shinoda, 2013), in which, unlike in honeybees, JH preserved its ancestral gonadotropic function reported also in bumblebees (Shpigler et al., 2014, 2016). Further relevant markers studied in both honeybees and bumblebees are the transcription factor Krüppel homolog 1 (Kr-h1) and the yolk protein vitellogenin (Vg). Kr-h1 is the first down-stream transcription factor responding to the activation of JH-specific receptors in developing insects (Jindra et al., 2013). Shpigler et al. (2010, 2014) showed that the ovarian development as well as Vg and Kr-h1 expression are JH-dependent in B. terrestris workers and that Kr-h1 expression is inhibited by the queen's presence. However, Vg's impact on social interactions seems to be much stronger than on the workers' reproductive status and in that case Vg is not regulated by JH signaling (Amsalem et al., 2014).

The investigation of IIS in insects is presently undergoing enormous progress (for a review see Vafopoulou, 2014). ILPs/IGFs and their specific insulin receptors (InRs) are structural, genetic and functional homologs of mammalian insulins and their receptors. In insects, IIS is involved in the regulation of all main physiological processes, including metabolic aspects of reproduction and diapause. Hence, IIS interacts with other principal signaling pathways, i.e., (1) Target of Rapamycin (TOR), a nutrient sensing responder, (2) JH, the main regulator of development and reproduction, and (3) Forkhead box protein O (FOXO), a transcription factor involved in stress tolerance, diapause, longevity and growth (Vafopoulou, 2014). In consequence, IIS participates in the regulation of insect polyphenism and caste differentiation of eusocial species (e.g., Koyama et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2015). For instance, nutrient sensing triggers IIS activation which induces elevation of JH titers necessary for queen development in honeybee larvae (Mutti et al., 2011). However, honeybees have developed idiosyncrasies that set them apart of the general pattern in insects. JH and vitellogenin (Vg) are negatively correlated in honeybees (Guidugli et al., 2005a) whereas in all other insects studied to date, the inverse pattern was observed (Wyatt and Davey, 1996).

Insect AKHs are peptidic neurohormones, structurally and functionally characterized in a number of solitary insects (Gäde, 2009). Their binding to specific G-protein coupled receptors (AKHRs) activates the mobilization of lipid, carbohydrate and/or proline stores (Gäde and Auerswald, 2003; Van der Horst, 2003). The role of AKH in social Hymenoptera is not well understood. In honeybees, AKH was in some studies either not detected (e.g., Veenstra et al., 2012) or only at low quantities in one subspecies, but not another (Lorenz et al., 1999; Woodring et al., 2003). Also, honeybees seem to not or hardly respond to AKH (Lorenz et al., 1999; Woodring et al., 2003). Similarly, workers of B. terrestris and B. hortorum did not react to AKH injections (Lorenz et al., 2001), but all investigated bumblebee species contained AKH (Lorenz et al., 2001), and AKH genes are conserved across Hymenoptera (Veenstra et al., 2012). A recent study suggested that IIS and AKHR are possibly co-regulated via JH signaling by means of a putative JH receptor (ultraspiracle, USP) and vitellogenin in honeybee workers (Wang et al., 2012).

Reproductive diapause regulation is thought to be conserved (Sim and Denlinger, 2013), although some taxa are likely to have discrete mechanisms. In bumblebees, the presence of queen diapause has been proposed to be a prerequisite for the evolution of sociality by co-option of the diapause-regulating gene network for new roles in caste differentiation (Hunt and Amdam, 2005; Hunt et al., 2007). Several studies have investigated the genetics underlying diapause in bumblebees (Kim et al., 2006, 2008; Colgan et al., 2011), including a very recent study communicating a genome-wide transcriptome comparison targeting the fat body of diapausing Bombus terrestris queens (Amsalem et al., 2015b). The latter study, concurrent with our own investigations, highlighted the functional association of the genes highly expressed in the queen's fat body with nutrient storage and stress resistance, as well as a different role of JH and Vg in diapausing bumblebee queens when compared to dipteran models. This further prompted our interest in a detailed dissection of a more complex set of endocrine markers related to the major transitions in the life of a bumblebee queen.

In the present study, we used qRT-PCR to characterize the expression levels of the following key genes of three major endocrine regulatory pathways in nine tissues, covering virgin, diapausing, and reproducing queens, as well as workers and males in the buff-tailed bumblebee, B. terrestris: (1) JH signaling —methyl farnesoate epoxidase (MFE), Krüppel homolog 1 (Kr-h1) and vitellogenin (Vg); (2) Insulin signaling/FOXO pathways—insulin growth factor 1 (IGF-1), locust insulin-related peptide like (LIRP-like), insulin-like peptide receptor 1 (InR-1), insulin-like peptide receptor 2 (InR-2), and forkhead box protein O (FOXO); (3) AKH signaling—hypertrehalosaemic prohormone-like (AKH) and gonadotropin-releasing hormone II receptor-like (AKHR ortholog gene). Expression profiles were characterized in brains, including corpora allata (CA) and corpora cardiaca (CC), labial glands, hypopharyngeal glands, gonads, flight muscles, the alimentary canal (crop, ventriculus, rectum), and fat bodies.

Materials and methods

Bumblebee rearing and collection

Colonies of B. terrestris terrestris (buff-tailed bumblebee) were kept at 28°C and a relative humidity of 60% in the laboratories of the Agricultural Research, Ltd., Troubsko, Czech Republic. We sampled five different phenotypes (ten individuals each): (1) Virgin queens collected 7 days after emergence; (2) Diapausing queens—mated queens kept at 4–7°C and sampled after 3 months, i.e., in the middle of hibernation; (3) Reproducing queens—collected from developing colonies with 10 to 15 workers, before the switch point, i.e., before the queen started to produce eggs that develop into haploid males (Duchateau and Velthuis, 1988); (4) Workers—9 days old workers sampled before the switch point and (5) Males—7 days old males, i.e., sexually mature and at the peak of marking pheromone production (Šobotník et al., 2008). The respective castes and queen life stages originated from nests of the same lineage of B. terrestris terrestris. Immediately after collection, individuals were frozen in crushed dry ice and stored at −80°C until dissections took place. This study complies with the current laws in the Czech Republic; no ethical approval was required for this study on laboratory-bred insects.

Tissue samples preparation

Individuals were dissected under a stereomicroscope on sterilized glass Petri dishes placed on crushed ice and in sterile, ice-cold RNAase-free Ringer solution. In order to map the organ-specific expression profile of investigated genes, we dissected nine different tissues from each individual: (1) brain—brain including both paired glands corpora cardiaca (CC) and corpora allata (CA); (2) hypopharyngeal and (3) labial glands—paired tissues from the head capsule; (4) flight muscles; (5) crop; (6) ventriculus; (7) rectum; (8) gonads (ovaries or testes); and (9) abdominal fat body—peripheral fat body attached to epidermis (see Supplementary Figure 1). Two samples of each tissue were pooled as one replicate, i.e., altogether five biological replicates per tissue of each B. terrestris phenotype were analyzed. Whereas the ovaries in virgins and diapausing queens were shrunk and transparent, ovary development of workers corresponded to stages I–II of oogenesis process (Duchateau and Velthuis, 1989). Immediately after dissection, all tissues were transferred to microcentrifuge tubes with 200 μL of TRI Reagent® (Sigma-Aldrich) on crushed ice and then stored at −80°C until RNA isolation.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

We extracted total RNA using TRI Reagent® (Sigma-Aldrich) following the manufacturer's protocol. RNA isolates were treated with RQ1 RNase-Free DNase (Promega) to remove traces of contaminant DNA. The cDNA template was prepared using the SuperScript® III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen by Life Technologies) on 400 ng of the corresponding total RNA with random hexamers. Primer pairs efficiency was tested using cDNA mixtures of all biological samples serially diluted into five concentrations and subsequently constructed standard curves (for selected primer pairs sequences and their respective efficiency values see Supplementary Table S1). Prior to qRT-PCR, cDNAs of all samples and the calibrator cDNA (i.e., the mixture of aliquots from all samples) were diluted ten-fold.

qRT-PCR analysis

We performed qRT-PCR using a LightCycler 480 qRT-PCR System (Roche) with SYBR green fluorescent labels and 200 nM of each primer. The PCR program was as follows: Initial denaturation for 15 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 55°C and 30 s at 72°C. The final extension was at 72°C for 2 min. A final melt-curve step was included post-PCR (ramping from 55°C to 95°C at 0.1°C steps every 5 s) to confirm the absence of any non-specific amplification. All biological samples were examined in two technical replicates. In order to allow comparison of all tested samples, calibrator cDNA was applied to a master-mix of specific genes on each plate. To obtain relative expression values for each target gene, generated Cp values were calibrated and normalized using the geometric mean of phospholipase A2 (PLA2) and elongation factor eEF-1 α (EF1) (Pfaffl, 2001). We selected housekeeping genes based on previous studies (Hornáková et al., 2010; Verlinden et al., 2013) and on the evaluation of PLA2, EF1 and arginine kinase using qRT-PCR across all biological samples using NormFinder (Andersen et al., 2004), in which PLA2 and EF1 were found to be the best combination for our experimental setup.

Sequence analyses

Insulin-like peptide sequences were analyzed using programs available at the Biology workbench server (http://workbench.sdsc.edu). Pairwise protein sequence alignment was performed using the EMBOSS Stretcher tool (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/psa/emboss_stretcher/).

Data processing and statistics

Results were plotted using the Prism graphic program (GraphPad Software, version 5.0, San Diego, CA, USA). The bars represent the mean of measurements ± SEM (n = 3–5). In order to process data with normal distribution, the results were log-transformed and then evaluated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison post-hoc test (p < 0.05). We corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg-method implemented in R. We generated heatmaps in R 3.2.3 using R package “gplots” (R. Development Core Team, 2015; Warnes et al., 2015). The matrix of log-transformed mean values of each gene's expression per specific phenotype and tissue was used for heatmap constructions.

Results and discussion

JH signaling

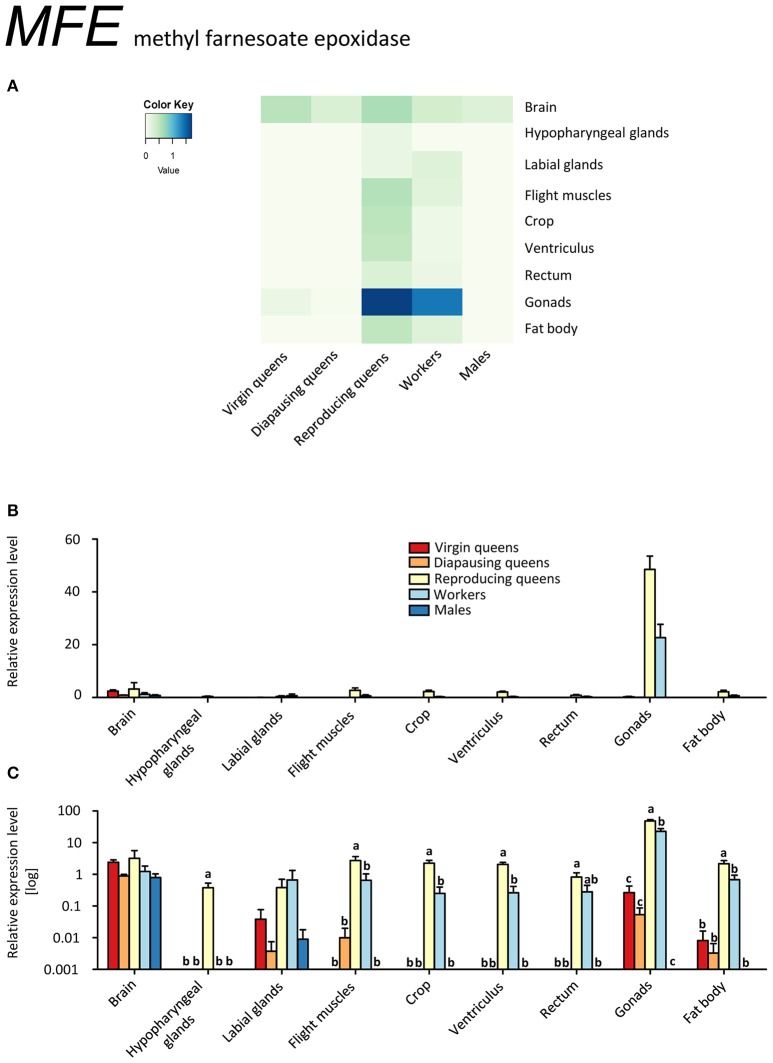

The highest transcript levels of methyl farnesoate epoxidase (MFE) were found in ovaries of workers and reproducing queens (Figures 1A–C, Supplementary Table S2). This is striking, since JH synthesis usually takes place in the corpora allata (CA) (e.g., Jindra et al., 2013) and occurs in the gonads in only a few species (reviewed in De Loof et al., 2013). Yet, since the alternative JH production sites are only poorly investigated so far, it is possible that the production of at least some JH in the ovaries may be more widespread than previously considered (De Loof et al., 2013). Even though a high JH synthesis is not automatically synonymous with elevated JH titers (Bloch et al., 2000), our results support the previously proposed conservation of the gonadotropic role of JH in bumblebees (Bloch et al., 2000; Shpigler et al., 2014, 2016; Amsalem et al., 2015b).

Figure 1.

qRT-PCR analysis of tissue-specific relative expression levels of methyl farnesoate epoxidase (MFE) across castes of B. terrestris. MFE is crucial in synthetizing juvenile hormone (JH). It is heavily upregulated in gonads of workers and reproducing queen. It is also found in brains of all samples (see main text). Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3–5) of normalized and rescaled expression levels. (A) Heatmap: Log-scale. Bar graphs: Relative transcript levels in linear scale (B) and log-transformed scale (C). Significantly different expression levels are indicated by different letters (p < 0.05).

The ability of reproducing queens and workers to produce JH in ovaries does not imply the presence of the whole JH biosynthesis pathway in this tissue. Strictly speaking, our results only indicate a high conversion rate of methyl farnesoate to JH in ovaries. A similar process, namely the conversion of JH acid to JH by juvenile hormone acid methyltransferase (JHAMT), was described in imaginal discs of post-wandering larvae of the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta (Sparagana et al., 1985). Potentially, CA release not only JH but also methyl farnesoate into the hemolymph that is then converted into JH by MFE in the ovaries. Therefore, our finding of high MFE expression in ovaries of bumblebee females may explain the reported discrepancy between low JH biosynthesis rates in CA but high JH titers and developed ovaries (Bloch et al., 2000). Allatectomized workers had greatly reduced JH titers in the hemolymph compared to controls (Shpigler et al., 2014), which could be explained by a lack of substrate for MFE under this scenario. The role of JH in the ovaries might be also to act locally in order to enhance vitellogenin uptake, as has been described for Dysdercus koenigii (Venugopal and Kumar, 2000) and Solenopsis invicta (Vargo and Laurel, 1994), without being secreted to the hemolymph.

Eight out of ten workers had developed ovaries in various stages; likely they were preparing to compete with the queen for male parentage (Duchateau and Velthuis, 1988). Their expression profile for MFE closely resembled that of fertile queens, consistent with the report by Harrison et al. (2015) who suggested that reproductive workers generally become more queen-like. This pattern, however, was not observed for the other genes under investigation. In general, our findings contrast with the situation in the honeybee (Bomtorin et al., 2014; Niu et al., 2014), in which almost no expression of MFE and relatively low expression of the direct upstream enzyme JHAMT were detected in ovaries (Bellés et al., 2005). This conspicuous difference is interpreted as an uncoupling of JH from the gonadotropic functions in the highly eusocial honeybees (Hartfelder and Emlen, 2012).

Gonads of virgin and diapausing queens had only low transcript levels, and males showed no expression outside the brain tissue (Figures 1A–C, Supplementary Table S2). MFE expression was relatively low in the brains of all samples. In hypopharyngeal glands, expression was absent except for low values in reproducing queens. Workers and reproducing queens showed low MFE expression values also in the remaining tissues, whereas virgin and diapausing queens showed spurious or no expression.

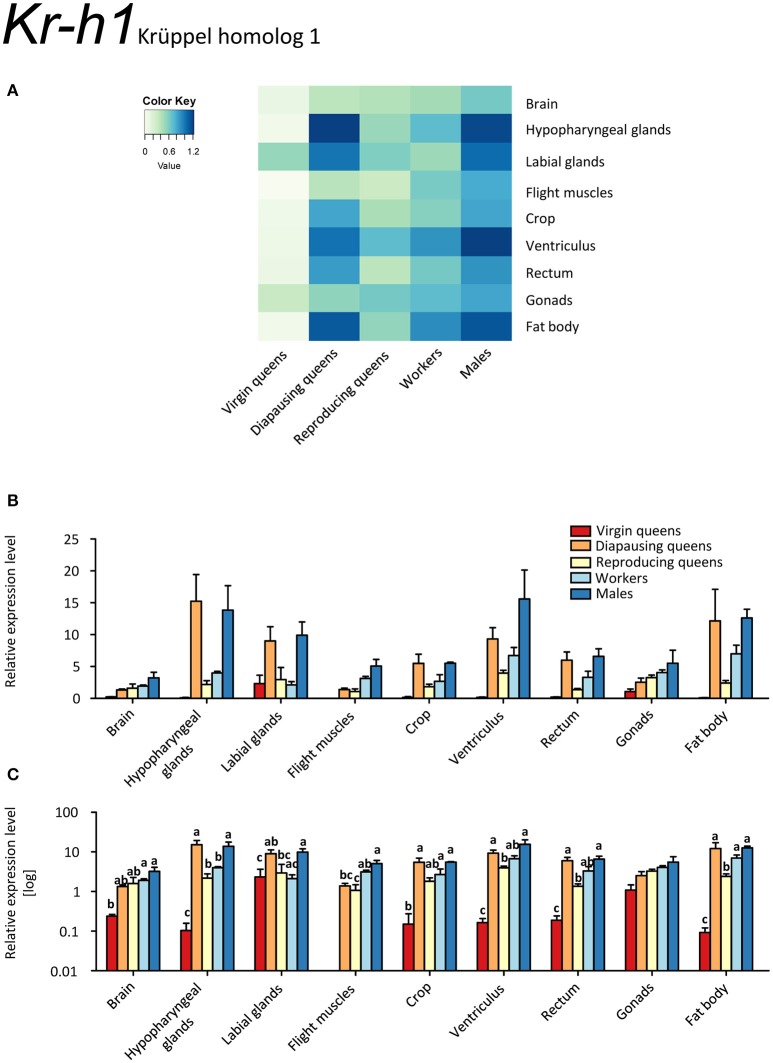

Our results indicate only low expression of Kr-h1 in virgin queens, except for slightly elevated values in the labial glands, and even lower expression in ovaries (Figures 2A–C, Supplementary Table S2). This is in stark contrast with the other females showing considerably higher expression levels, and to males who had the highest expression values in all tissues but labial glands. Reproducing queens were somewhat intermediary between the very low levels in virgins and the rather high levels in diapausing queens. Across all samples, particularly high expression occurred in labial and hypopharyngeal glands, ventriculus, and fat body.

Figure 2.

qRT-PCR analysis of tissue-specific relative expression levels of Krüppel homolog 1 (Kr-h1) across castes of B. terrestris. Kr-h1 is a transcription factor downstream of juvenile hormone receptors. It is downregulated in virgin queens, and upregulated in males and diapausing queens (see main text). Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3–5) of normalized and rescaled expression levels. (A) Heatmap: Log-scale. Bar graphs: Relative transcript levels in linear scale (B) and log-transformed scale (C). Significantly different expression levels are indicated by different letters (p < 0.05).

Among the studied queen life stages, the highest Kr-h1 expression was recorded in most tissues of diapausing queens, except for flight muscles and ovaries (Figures 2A–C, Supplementary Table S2). Conversely, virgins and reproducing females had low expression of Kr-h1. This expression pattern contrasts sharply with that of the two other markers of JH signaling, MFE and Vg (Figures 1A–C, 3A–C, respectively). This finding is also contradictory to the only available comparative data on females of the red firebug, Pyrrhocoris apterus (Bajgar et al., 2013), where Kr-h1 levels were low in diapausing females and increased immediately in response to external application of JH mimics. On the other hand, a recent work revealed that mating can trigger Kr-h1 upregulation in the gut of Drosophila melanogaster females together with gut tissue remodeling for increased lipid metabolism (Reiff et al., 2015). Thus, one may speculate whether Kr-h1 brings about tissue reconstruction in queens after mating during the course of diapause. Nevertheless, at the present state of knowledge, we are still far from a satisfactory explanation for why Kr-h1's expression pattern is incongruent with other JH signaling markers.

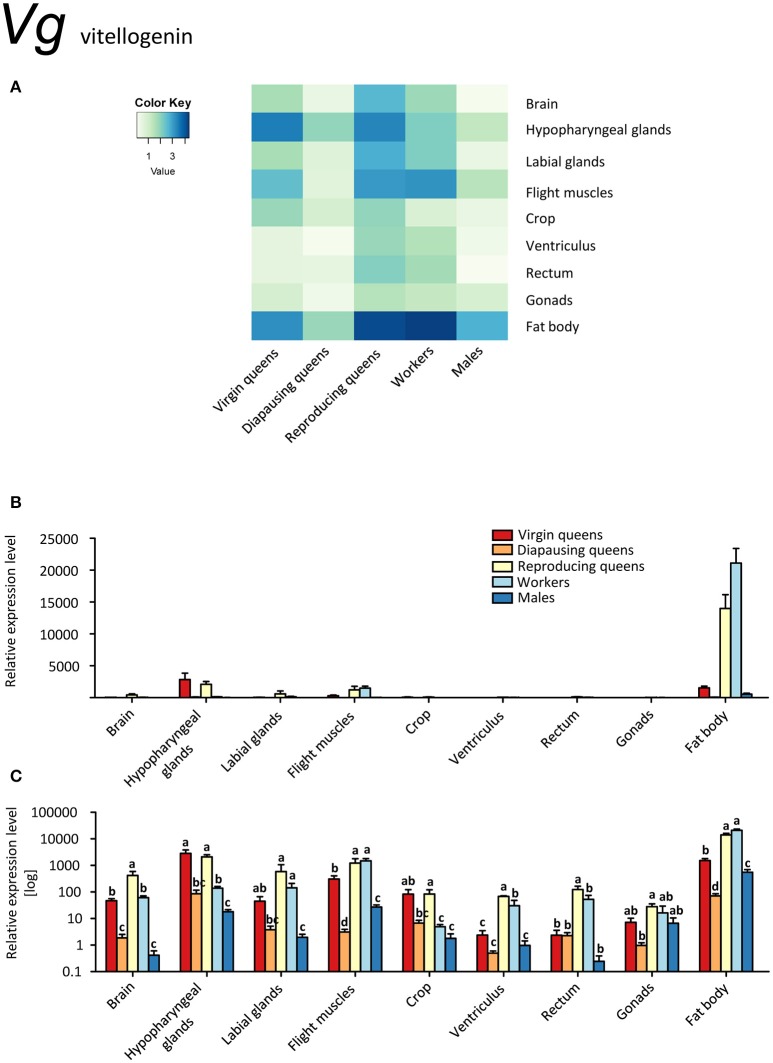

Figure 3.

qRT-PCR analysis of tissue-specific relative expression levels of vitellogenin (Vg) across castes of B. terrestris. Vg is a yolk protein with multiple functions in immunity and behavioral regulation. It is highly upregulated in fat body of all castes, and generally lowest in males and diapausing queens (see main text). Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3–5) of normalized and rescaled expression levels. (A) Heatmap: Log-scale. Bar graphs: Relative transcript levels in linear scale (B) and log-transformed scale (C). Significantly different expression levels are indicated by different letters (p < 0.05).

Vitellogenins, large phosphoglycolipoproteins, have been attributed a plethora of functions. They are best known for their role as yolk precursors in oviparous animals (Valle, 1993). Additionally, they also act as carriers for hormones, vitamins, metals, and others (reviewed in Sappington and Raikhel, 1998). Vg shows antimicrobial properties and is involved in immunity (Amdam et al., 2004; Sun and Zhang, 2015), it has anti-oxidative (Havukainen et al., 2013; Sun and Zhang, 2015), and potentially anti-inflammatory properties (Havukainen et al., 2013; Salmela et al., 2016). Further, expression of Vg genes correlates with castes and behavior in some ants (Wurm et al., 2011; Corona et al., 2013) and might be involved in caste determination in ants (Libbrecht et al., 2013) and honeybees (Barchuk et al., 2002). Thus, Vg clearly has many more functions than being a yolk precursor only. Moreover, as in other hymenopterans, three Vg-like genes with as yet unknown function are present in several bumblebee species, including B. terrestris (Harrison et al., 2015), suggesting that these gene duplications allowed new functions to evolve (Morandin et al., 2014). Among them the reproducing female specific gene marked “Vg1” (Morandin et al., 2014; Harrison et al., 2015) is the gene variant studied in this work.

Vg was expressed in all studied tissues (Figures 3A–C). Reproducing queens showed the highest, whereas diapausing queens and males the lowest expression levels. As expected, the strongest expression occurred in the fat bodies, particularly in reproducing queens and workers (up to 38 times more transcripts than in virgins and males; Figures 3B,C).

Our data on MFE and Vg expressions (Figures 1A–C, 3A–C) are in line with the gonadotropic function of JH signaling that leads to increased vitellogenin synthesis in reproducing females (Amsalem et al., 2014; Shpigler et al., 2014). Their low expression levels during diapause are characteristic for a reproductive arrest in hibernating insects (e.g., Goodman and Cusson, 2012). Our findings contrast with the data of Amsalem et al. (2015b) who found no differences in Vg expression in fat bodies of mated, diapausing queens, and post diapause foundresses. Potentially, these differences stem from the time of sampling, i.e., before (Amsalem et al., 2015b) and after the emergence of workers (the present study). Amsalem et al. (2015b) suggested this discrepancy with most insects might be a sign of derived functions of vitellogenin in social insects. This view is partially supported by our observations in other tissues.

Besides fat body tissues, also brains, both glands and flight muscles manifested a considerable upregulation. While in the fat body Vg likely serves the canonical storage and yolk protein role, its ubiquitous expression in virtually all tissues, including brain, suggests additional functions. Interestingly, higher Vg expression was found in brains and hypopharyngeal glands of reproducing queens compared to workers with vitellogenic ovaries (i.e., 7 and 15 times in brains and hypopharyngeal glands, respectively; Figures 3A–C, Supplementary Table S2). These are the only tissues with Vg upregulated in comparison with workers. Since Vg expression in the brains of some insects is linked to caste- or reproduction-related behavior and physiology (Corona et al., 2007; Roy-Zokan et al., 2015), it appears likely that this finding could be linked to a queen-specific role of Vg.

In most insects, JH and Vg are positively correlated, but there are also cases where Vg became uncoupled or even interacts negatively with JH (Amsalem et al., 2014 and references therein). Here, we confirm that Vg correlates with egg-laying in bumblebee queens (Amsalem et al., 2014; Harrison et al., 2015). Our results are largely in agreement with data on whole body extracts (Harrison et al., 2015) and head extracts (Amsalem et al., 2014), reporting higher Vg expression in the heads of reproducing queens than in virgins and sterile or fertile workers. The observed differences between tissues in our study demonstrate the value of detailed investigations. For instance, we found Vg transcripts in varying abundances in the brain, labial glands, and the highest expression in hypopharyngeal glands, all situated within the head capsule. Vg protein has been detected in honeybee nurse head fat body and likely in glia cells (Seehuus et al., 2007; Münch et al., 2015). Reports of Vg transcripts in honeybee brain might be due to contamination with head adipocytes (Münch et al., 2015), but could as well signal genuine, probably also age-dependent, though rather low transcription levels. The function of Vg in glia cells or the brain in general remains unknown; it has been speculated that they might suppress inflammatory processes (Münch et al., 2015).

The fat body is regarded as the main location of Vg synthesis (e.g., Arrese and Soulages, 2010). Also in the present study, transcript levels were ca. 7 times higher in the fat body than in tissues with the next highest expression (hypopharyngeal glands, labial glands, flight muscles).

We show that Vg transcripts are also found in male and female gonads. Vitellogenesis in ovaries is not unusual in other insects (reviewed in Valle, 1993), and honeybee queens do express Vg in their ovaries as well (Guidugli et al., 2005b). Guidugli et al. (2005b) could not detect Vg expression in worker ovaries; however, it would seem they investigated only sterile workers, and we expect the fertile workers to express Vg in ovaries. Seehuus et al. (2007) confirmed the presence of Vg proteins in worker ovaries, but did not study their origin.

In insects, Vg is not common in males, but not exceptionally rare (reviewed in Valle, 1993); in social insects it occurs for instance in males of termites (Weil et al., 2009), stingless bees (Dallacqua et al., 2007), honeybees (Colonello-Frattini et al., 2010), and two species of bumblebees (Li et al., 2010; Harrison et al., 2015).

Unlike in honeybees, where Vg mRNA levels in abdomens, fat body and male accessory glands were only moderate in 1-day-old drones and then declined (Piulachs et al., 2003; Corona et al., 2007; Colonello-Frattini et al., 2010), we found very high transcript levels of Vg in fat bodies of mature males. Additionally, Vg was expressed in hypopharyngeal glands, flight muscles, and gonads. This supports once again the expected pleiotropic function of Vg. Colonello-Frattini et al. (2010) interpret the finding of Vg in male gonads as a “cross-sexual transfer” from traits evolved in female castes. Piulachs et al. (2003) argue that it is not a partial development of female traits, because it is also found in diplo-diploid species, and suggest that in Hymenoptera at least, it is related to sociality. Currently, there are not enough studies on non-social Hymenoptera to verify this hypothesis.

Cephalic labial glands are well known as the synthesis site of sex (marking) pheromones in bumblebee males (Žáček et al., 2013). Their role in females, where they are drastically reduced, remains elusive.

Unlike in honeybees, hypopharyngeal glands are developed in all bumblebee castes and in both sexes. Similar to honeybees, these glands produce a BtRJPL (B. terrestris royal jelly protein-like) protein, an ortholog of honeybee major royal jelly proteins (Kupke et al., 2012). Although these proteins are orthologs, the exact physiological function in bumblebees remains poorly understood (Albert et al., 2014). Likely, the ancestral role of major royal jelly proteins was pre-digestive food modification, comparable to saliva (Kupke et al., 2012), and the nutritive function in honeybees is derived. Similarly, the hypopharyngeal glands secretion contains digestive enzymes such as amylase and invertase (Pereboom, 2000). Nevertheless, the bumblebee hypopharyngeal glands might also serve as storage for Vg, analogous to the fat body, as was suggested for honeybees by Amdam and Omholt (2002).

Head fat body tissue was clearly visible in our dissections and firmly attached to the chitinous elements in the head. While we cannot rule out that some adipocytes might have been sticking to brains or labial glands during the dissections (compare Münch et al., 2015), this would not explain the high expression levels in hypopharyngeal glands. In general, the ubiquitous occurrence of Vg in a variety of different tissues suggests that it might serve as regulator of immune functions, including anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative defense, as reported for honeybees (Amdam et al., 2004; Havukainen et al., 2013).

Insulin signaling

A search for putative homologs of known insect genes of IIS in the B. terrestris genome using BLAST (Madden, 2003) unveiled two pairs of insulin peptides and receptors (see Supplementary Table S1). These were insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and locust insulin-related peptide-like (LIRP) as the predicted ligands, and insulin-like peptide receptors InR-1 and InR-2. The sequence analysis of the two B. terrestris insulin peptides revealed high identity with the IGF-1 and LIRP from Apis florea. Similarily, their sequences matched with the respective homologs of human IGF-1 and Locusta migratoria LIRP (see Supplementary Figure 2). Therefore, we use the terms “IGF-1” and “LIRP”, respectively, for these two peptides.

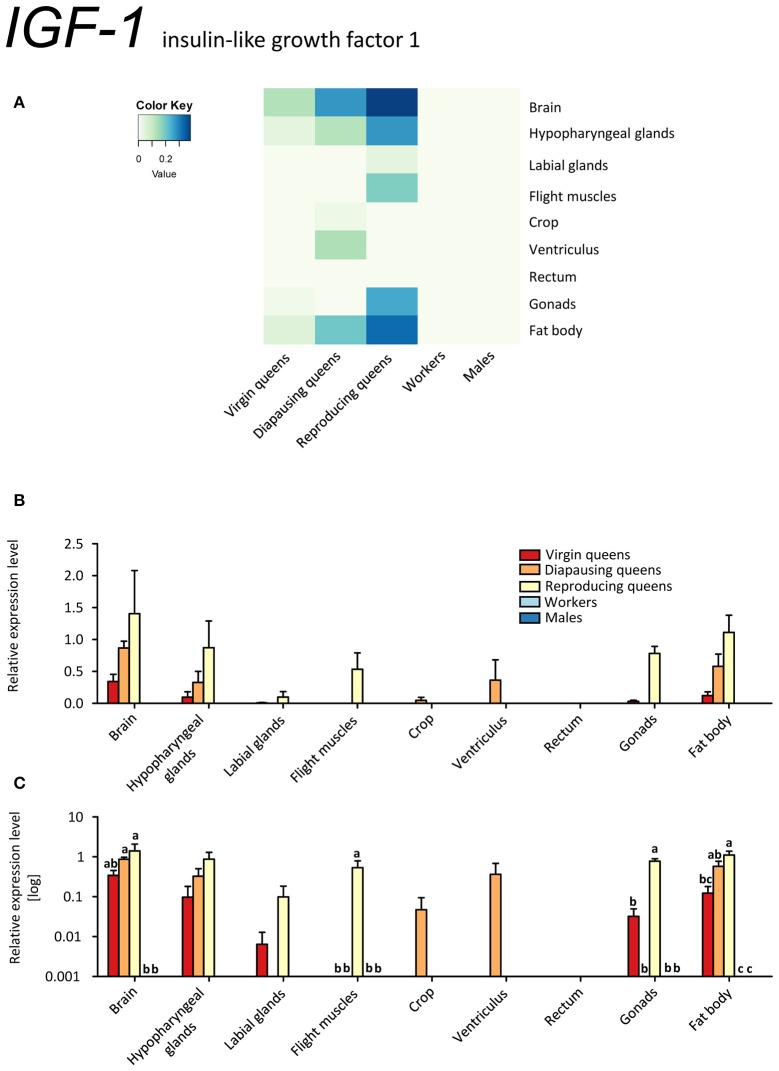

IGF-1 was expressed exclusively in queens (Figures 4A–C). In virgins, only spurious expression was detected in brain, hypopharyngeal glands, fat body, and ovaries. Higher expression values were observed in diapausing queens, where the ventriculus also contained IGF-1 transcripts. The highest expression occurred in brain, hypopharyngeal glands and fat body tissues of reproducing queens (~2 to 3 times higher than in diapausing queens and 4 to 10 times higher than in virgins; Figures 4A–C, Supplementary Table S2). Here, IGF-1 was present in all investigated tissues except for the digestive tract.

Figure 4.

qRT-PCR analysis of tissue-specific relative expression levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) across castes of B. terrestris. IGF-1 is part of the IIS signaling involved in reproduction and diapause. It is queen-specific (i.e., absent in workers and males) and lowest in virgin queens (see main text). Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3–5) of normalized and rescaled expression levels. (A) Heatmap: Log-scale. Bar graphs: Relative transcript levels in (B) linear scale; and (C) log-transformed scale. Significantly different expression levels are indicated by different letters (p < 0.05).

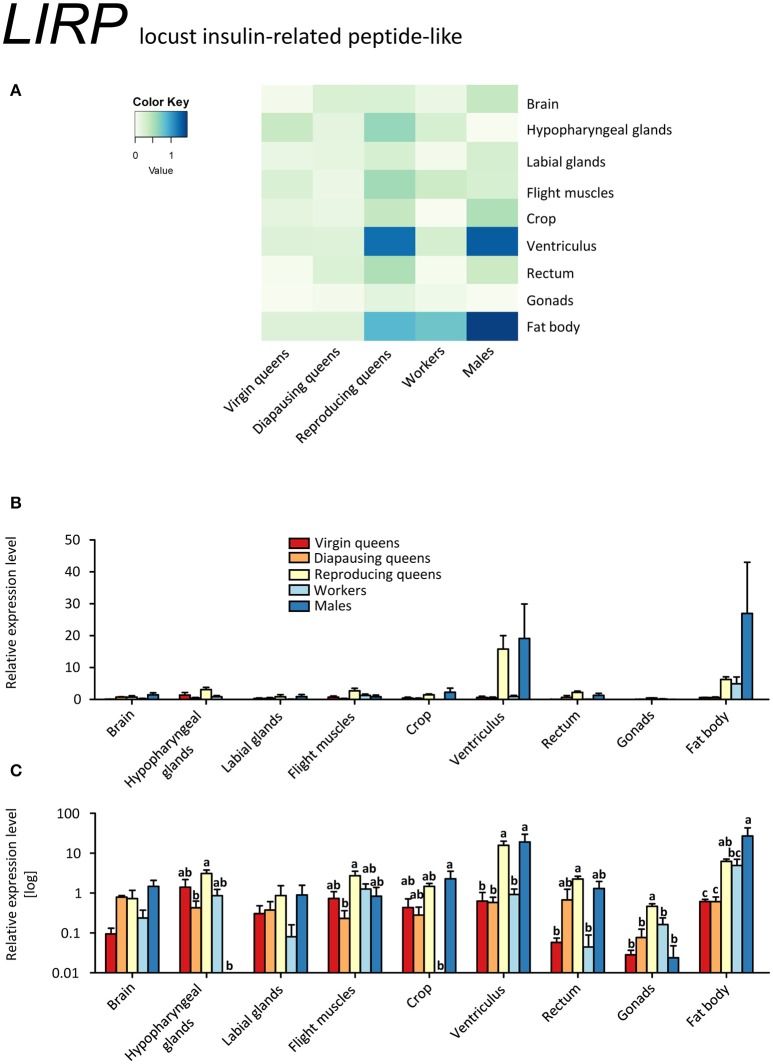

In contrast to IGF-1, LIRP was expressed in virtually all samples, except for males' hypopharyngeal glands and workers' crop (Figures 5A–C, Supplementary Table S2). This is consistent with the findings in desert locusts, Schistocerca gregaria (Badisco et al., 2008). The highest expression levels occurred in the ventriculus and fat body of reproducing queens and males. Reproducing queens had often higher expressions than virgins or diapausing queens (Figures 5A–C, Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 5.

qRT-PCR analysis of tissue-specific relative expression levels of locust insulin-related peptide-like 1 (LIRP) across castes of B. terrestris. LIRP is part of the insulin signaling involved in reproduction and diapause. It is most abundant in fat body and ventriculus of males and reproducing queens (see main text). Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3–5) of normalized and rescaled expression levels. (A) Heatmap: Log-scale. Bar graphs: Relative transcript levels in linear scale (B) and log-transformed scale (C). Significantly different expression levels are indicated by different letters (p < 0.05).

Since transcripts of both B. terrestris insulin-related peptides are the most abundant in reproducing queens, the IIS in bumblebees is apparently correlated with upregulated JH signaling and high nutritional and reproductive status, as is also reported for solitary insects (Badisco et al., 2013). This is supported by increased IGF-1 expression in reproducing queens, which correlates with the pattern of Vg in the same tissues, especially in brain and hypopharyngeal glands, flight muscles and fat body (compare Figures 3A–C, 4A–C). However, IGF-1 transcripts are absent in workers with developing ovaries showing an upregulated JH signaling (Vg and MFE expression). We hypothesize that suppressed IGF-1 expression in workers is linked to the developmental arrest in vitellogenic ovaries in queen-right colonies.

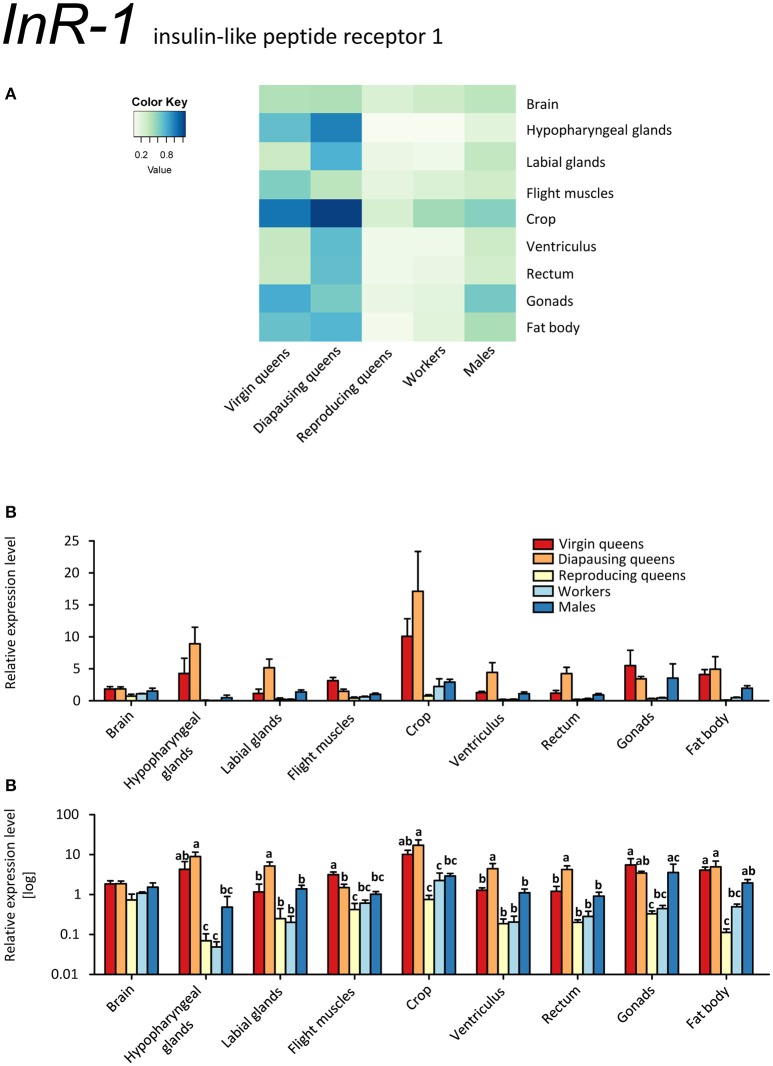

InR-1 transcripts were detected in all samples. By far the highest expression occurred in tissues of virgin and diapausing queens (Figures 6A–C). By contrast, reproducing queens showed the lowest expression values (for all tissues except cephalic glands; see Figures 6A–C). The InR-1 expression pattern in queens is inverse to the expression of its putative ligands IGF-1 and LIRP (compare Figures 4A–C, 5A–C, and 6A–C). Unexpectedly high expression occurs in the crop in all stages but the reproducing queens. Males' testes also showed InR-1 transcript levels as elevated as in males' crop.

Figure 6.

qRT-PCR analysis of tissue-specific relative expression levels of insulin-like peptide receptor 1 (InR-1) across castes of B. terrestris. InR-1 is a receptor involved in insulin signaling. It is upregulated in virgin and diapausing queens, especially in crop and hypopharyngeal glands (see main text). Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3–5) of normalized and rescaled expression levels. (A) Heatmap: Log-scale. Bar graphs: Relative transcript levels in linear scale (B) and log-transformed scale (C). Significantly different expression levels are indicated by different letters (p < 0.05).

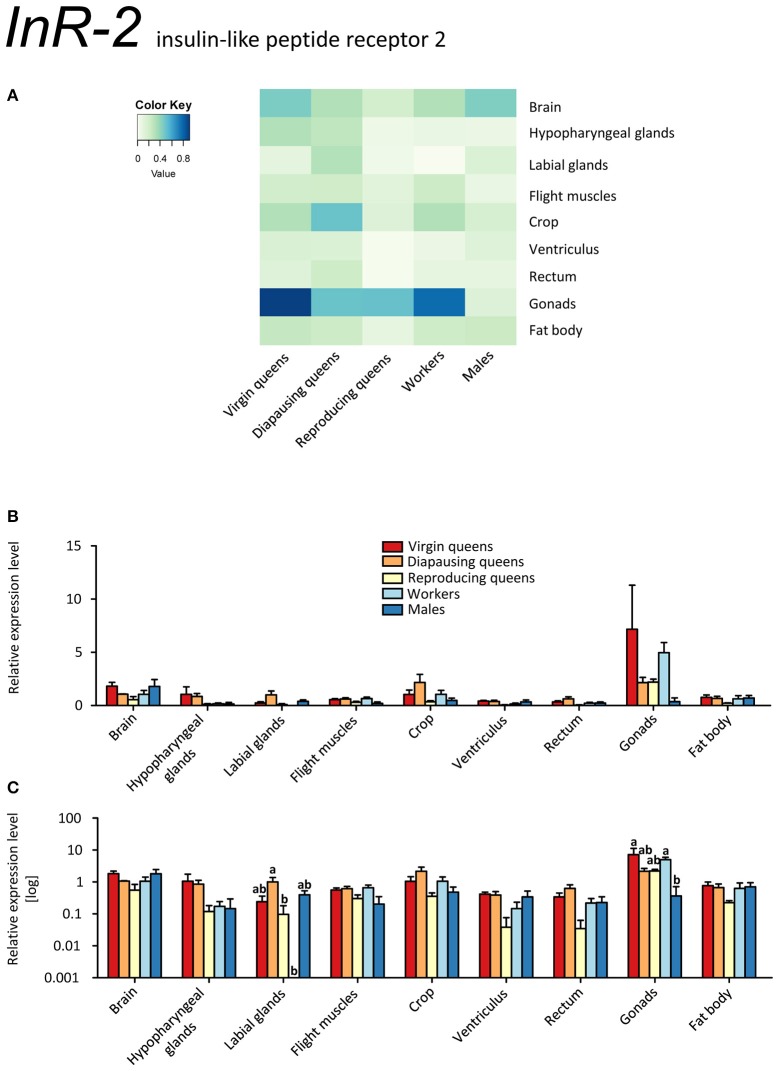

InR-2 was expressed ubiquitously, but at low levels, in all stages, except for workers' labial glands (no transcript detected) (Figures 7A–C, Supplementary Table S2). The highest expression occurred in the ovaries of all females. The high expression levels in the gonads might point at a role in reproduction, because IIS controls synthesis of JHs and ecdysteroids, i.e., the main regulators of insect reproductive physiology (reviewed in Antonova et al., 2012; Badisco et al., 2013). Yet, it is clear that InR-2 plays not a single role, given the widespread expression across almost all tissues. If InR-2 is indeed involved in reproduction, the elevated expression in workers' gonads would suggest once again that some workers were prepared to reproduce during the competition phase (Duchateau and Velthuis, 1988).

Figure 7.

qRT-PCR analysis of tissue-specific relative expression levels of insulin-like peptide receptor 2 (InR-2) across castes of B. terrestris. InR-2 is a receptor involved in insulin signaling. It is upregulated in gonads (see main text). Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3–5) of normalized and rescaled expression levels. (A) Heatmap: Log-scale. Bar graphs: Relative transcript levels in linear scale (B) and log-transformed scale (C). Significantly different expression levels are indicated by different letters (p < 0.05).

Expressions of InRs were studied in two other hymenopterans, A. mellifera and the fire ant Solenopsis invicta (Ament et al., 2008; de Azevedo and Hartfelder, 2008; Lu and Pietrantonio, 2011). Similar to the InR-1 findings shown in the present study, InRs' transcripts were more abundant in virgin queens of S. invicta compared to workers (Lu and Pietrantonio, 2011). In A. mellifera, IIS genes were upregulated in foragers vs. nurses, whereas the expression of AmAKH and AmAKHR did not differ significantly (Ament et al., 2008; de Azevedo and Hartfelder, 2008). However, these reports focused on honeybee phenotypes with regard to age polyethism and thus are difficult to compare with our worker sampling.

Most insects express one insulin receptor which is likely to bind the insulin-like peptides and insulin growth factors (Okamoto et al., 2009). For instance, the insulin receptor identified in Drosophila (dInR) binds the insulin-like peptides dILP1-5 as well as the insulin growth factor-like peptide dILP6 (Brogiolo et al., 2001; Okamoto et al., 2009). Thus, we can anticipate that also InR-1 and InR-2 are activated by either IGF-1 or LIRP.

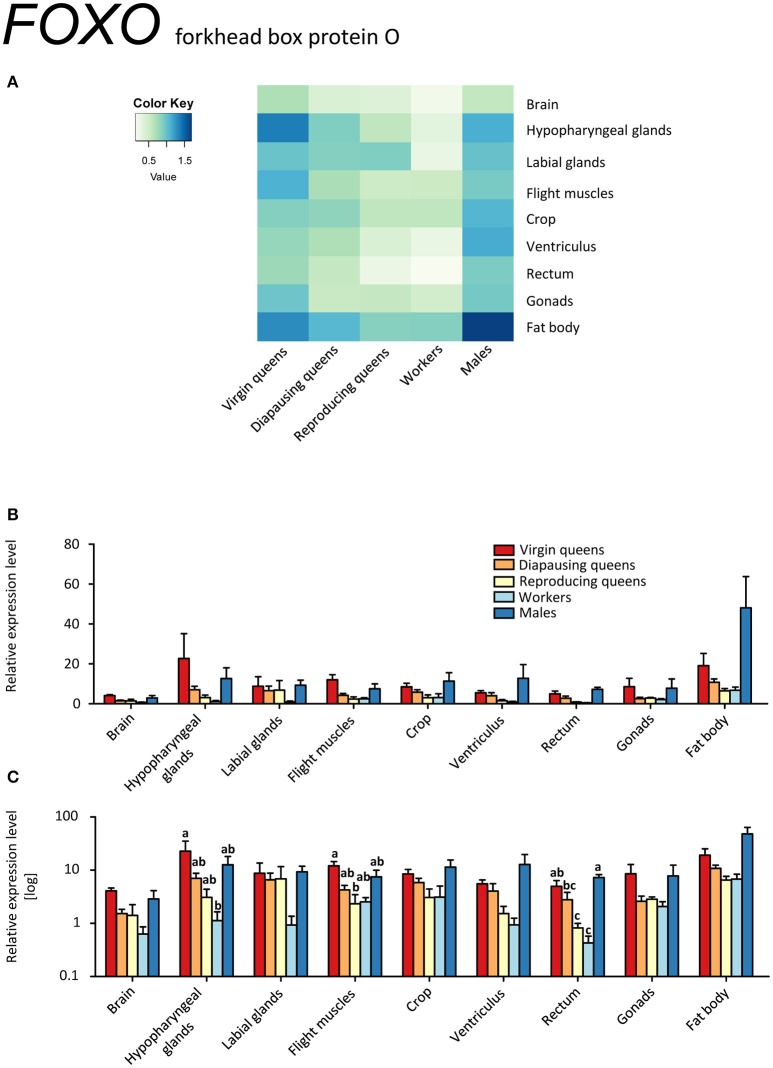

Interestingly, we found opposite expression levels of insulin-like peptides and their respective receptors. Whereas the genes coding for both ligands (IGF-1, LIRP) had high expression, InR-1 showed the lowest expression (reproducing queens). Conversely, low IGF-1 and LIRP transcript levels occurred when InR-1 was upregulated in the same tissue (virgins, compare Figures 4A–C and 6A–C). It was previously shown that “both in Drosophila and mammals, insulin receptor (InR) represses its own synthesis by a feedback mechanism directed by the transcription factor dFOXO/FOXO1” (Puig and Tjian, 2005). Specifically, in Drosophila, dFOXO directly activates dInR transcription, and its action can be modulated by nutritional status. This is consistent with our records in virgins as FOXO and InR-1 transcriptions were upregulated simultaneously, whereas IGF-1 and LIRP showed very low expression across investigated tissues (Figures 4A–C, 5A–C, 6A–C, and 8A–C).

Figure 8.

qRT-PCR analysis of tissue-specific relative expression levels of forkhead box protein O (FOXO) across castes of B. terrestris. FOXO is a transcription factor involved in stress tolerance, diapause, longevity, and growth. FOXO transcription is lower in workers and reproducing queens than in other castes (see main text). Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3–5) of normalized and rescaled expression levels. (A) Heatmap: Log-scale. Bar graphs: Relative transcript levels in linear scale (B) and log-transformed scale (C). Significantly different expression levels are indicated by different letters (p < 0.05).

It is tempting to propose that the extremely high expression of InR-1 in all tissues of virgins and diapausing queens compared to all other samples is related to their high food (energy) intake prior to diapause by virgins and its consequent preservation by diapausing queens (Badisco et al., 2013). By contrast, reproducing queens have relatively low level of InR-1 transcripts, indicating that they are not storing nutrients but rather spending them.

The FOXO transcription factor is situated downstream of IIS and JH signaling, and is considered to be the main regulator of insect diapause which includes, among others, cell cycle arrest and fat accumulation in early diapause stage (reviewed in Sim and Denlinger, 2013). Besides diapause, FOXO controls stress tolerance, longevity, and growth in insects (reviewed in Vafopoulou, 2014). In our model, FOXO was expressed in all investigated tissues (Figures 8A–C). Elevated expression occurred across tissues of males and virgins, especially in fat body and hypopharyngeal glands. We hypothesize that higher FOXO expression in virgins' tissues correlates with its regulatory role in energy reserve accumulation during the prehibernation stage, as is also suggested by high InR-1 levels.

AKH/AKHR signaling

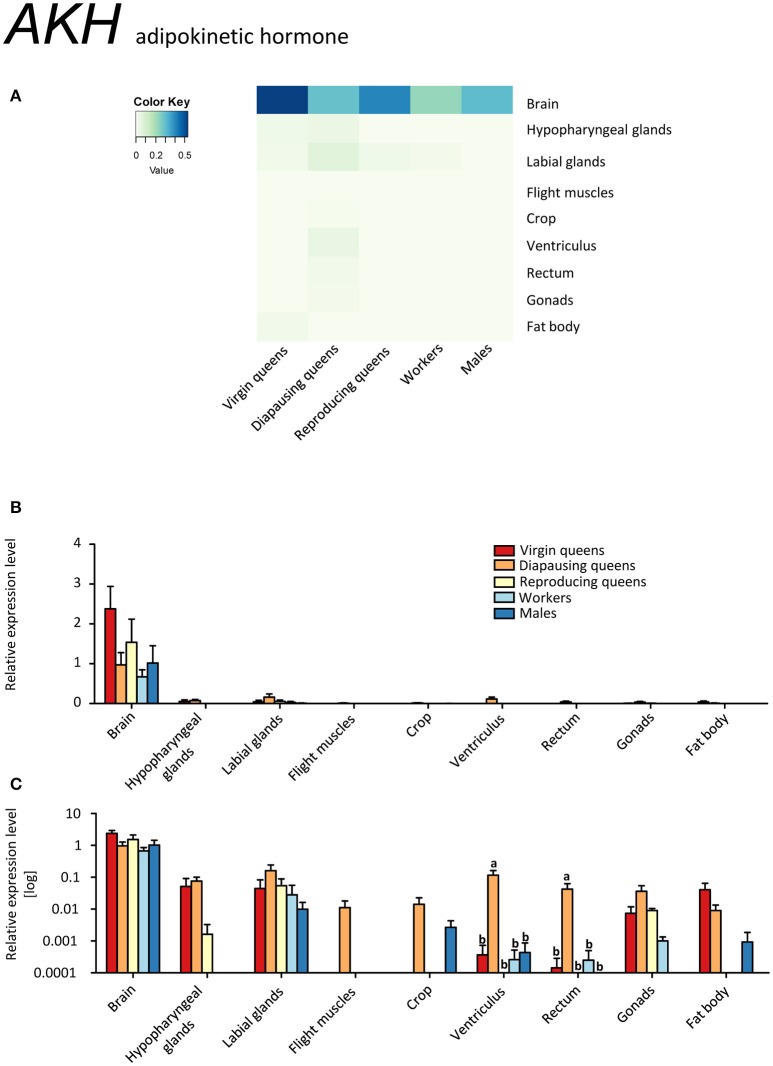

AKH was expressed in brain samples, which included also CC and CA, of all investigated specimens (Figures 9A–C, Supplementary Table S2). Unexpectedly, a minor expression was also detected in other tissues. AKH expression outside of CC was previously reported in fat bodies of A. mellifera workers (Wang et al., 2012) and brain tissues (i.e., without CC-CA) of the red firebug, P. apterus, where the translated neuropeptide was also localized and quantified (Kodrík et al., 2015). However, the significance of these observations is not clear yet.

Figure 9.

qRT-PCR analysis of tissue-specific relative expression levels of adipokinetic hormone (AKH) across castes of B. terrestris. AKH is involved in the mobilization of lipid, carbohydrates and/or proline stores. AKH is mainly expressed in brain-CC-CA samples, but minor expression occurred also in other tissues (see main text). Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3–5) of normalized and rescaled expression levels. (A) Heatmap: Log-scale. Bar graphs: Relative transcript levels in linear scale (B) and log-transformed scale (C). Significantly different expression levels are indicated by different letters (p < 0.05).

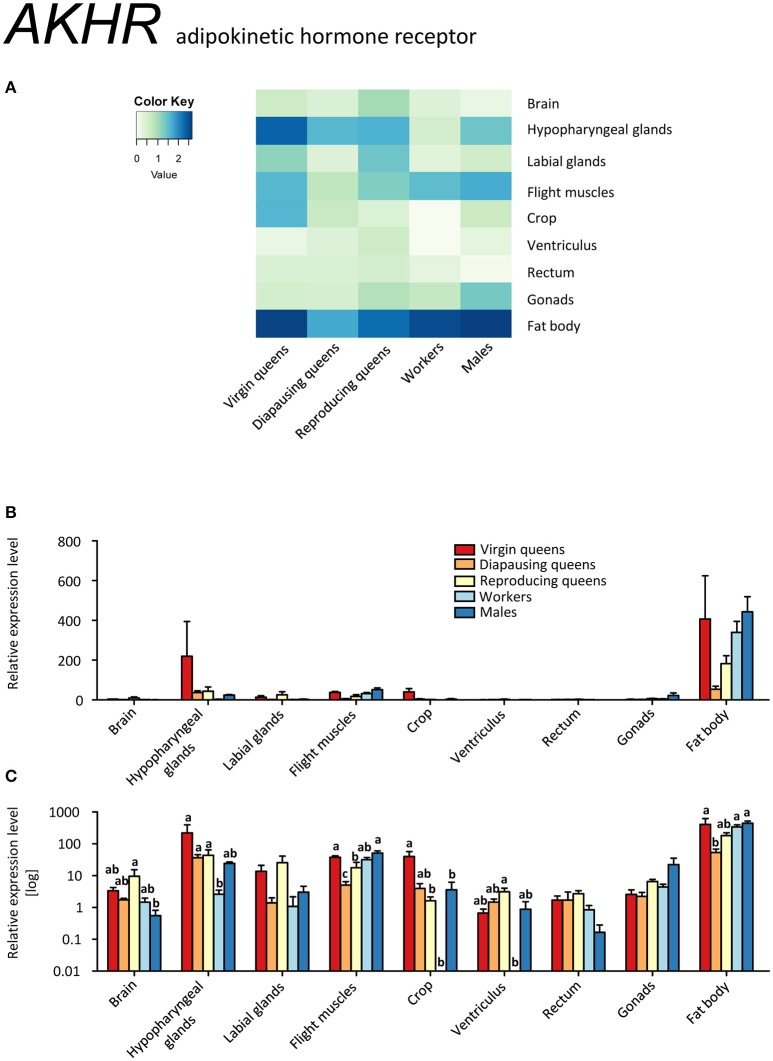

AKHR was ubiquitously expressed across all samples (Figures 10A–C, Supplementary Table S2). Its highest expression was observed in the fat body and flight muscles, as expected for a receptor involved in the release of carbohydrates and lipids upon high energy demand (Gäde and Auerswald, 2003; Gäde, 2009). Motionless, diapausing queens had the lowest levels, in agreement with their low energy demand. Surprisingly high expression levels of AKHR were recorded in hypopharyngeal glands, especially in virgin queens. As for other genes, AKHR expression in hypopharyngeal glands paralleled that of fat bodies. Whereas the presence of hypopharyngeal glands across bumblebee sexes and castes, as well as the synthesis of royal jelly-like protein within its cells, were reported recently (Albert et al., 2014), the overall significance of the glands remains unresolved. It was proposed that the original role of major royal jelly proteins was pre-digestive food modification, comparable to saliva (Kupke et al., 2012), and that the nutritive function seen in honeybees is derived. Similarly, the hypopharyngeal glands secretion contains digestive enzymes such as amylase and invertase (Pereboom, 2000). These reports together with our findings point to common mechanisms of endocrine regulation for food uptake and digestion as well as nutrient storage and release. Since AKH is actively involved in the control of digestive processes (Bodláková et al., 2016 and references therein), we propose that the high AKHR expression in hypopharyngeal glands is related to the regulation of digestive enzymes via AKH signaling.

Figure 10.

qRT-PCR analysis of tissue-specific relative expression levels of adipokinetic hormone receptor (AKHR) across castes of B. terrestris. AKHR is involved in the regulation of energy storage. It is mainly expressed in fat body and hypopharyngeal glands (see main text). Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3–5) of normalized and rescaled expression levels. (A) Heatmap: Log-scale. Bar graphs: relative transcript levels in linear scale (B) and log-transformed scale (C). Significantly different expression levels are indicated by different letters (p < 0.05).

Glycogen from skeletal muscles is considered to be one of the primary energy substrates for the initiation of insect flight (Beenakkers et al., 1984) due to AKH's capacity to activate glycogen phosphorylase (Gäde and Auerswald, 2003; Van der Horst, 2003). Indeed, the elevated expression of AKHR in the flight muscles of all active fliers (i.e., virgins, workers, and males; Figures 10A–C) supports this assumption.

Queen's life cycle vs. AKH/AKHR signaling

Diapausing queens revealed the lowest AKHR expression, except for the digestive tract (Figures 10A–C, Supplementary Table S2). Moreover, the expression of AKH in the brain stays high over the course of the queen's life, and is higher than in workers and males. Studies on the regulation of AKH and AKHR gene expression in different phenotypes or in response to changes in the environment are limited to aphid models so far (Jedličková et al., 2015). The possible involvement of AKH/AKHR signaling in energy storage mobilization during diapause emerged with records of high sensitivity of diapausing P. apterus females to AKH application when compared to non-diapausing conspecifics (Socha and Kodrík, 1999). Here, we documented that AKH signaling in diapausing B. terrestris queens is downregulated via reduced AKHR expression. However, since the AKH of diapausing queens is expressed at similar levels in virgins and reproducing females, we cannot exclude that the significant depletion of glycogen during the course of hibernation reported by Amsalem et al. (2015b) may be attributed to the AKH/AKHR signaling.

Conclusions

The virgin stage is characterized by the search for food and energy accumulation via upregulated FOXO, downregulated IIS and JH signaling and relatively high AKH/AKHR signaling. AKH expression is significantly higher than in other active fliers, i.e., workers and males, in line with the highest need for energy mobilization in virgin queens for active search of food prior to mating and hibernation. The Kr-h1 expression pattern is opposite to that of Vg not only in virgins, but also in all other investigated phenotypes. Hence, it is unlikely that this transcription factor is directly involved in reproduction of bumblebees. The morphogenetic factor Kr-h1 is known to be engaged, among others, in cell division, taking place especially in ovaries of reproducing queens and workers and testes of males, and tissue remodeling in mated females, possibly present also in mated diapausing queens. Therefore, we hypothesize that the striking downregulation of Kr-h1 expression in virgins might be connected to the absence of these processes.

Diapausing queens showed the expected downregulation of JH signaling, i.e., low MFE and Vg expression. Kr-h1 occurred at surprisingly high abundances. We suggest that this may be due to tissue reconstruction in mated queens prior to upcoming reproduction. Queen-specific IGF-1 signaling is active in diapausing females as well. Thus, together with AKH/AKHR, IIS could be involved in co-regulation of energy turnover from the fat body storage during hibernation.

Reproductive status is unequivocally defined by upregulated JH signaling (MFE and Vg) and IIS, highlighted by suppressed InR genes probably due to highest values of IGF-1 and LIRP. Specifically, IGF-1 was found to be a queen-specific insulin-like hormone. Thus, we propose it to play an essential role in the completion of egg development.

Workers showed the same regulation pattern of MFE and Vg as reproducing queens. By contrast, since LIRP is downregulated and IGF-1 expression is even absent, the IIS is the most visible difference between workers and reproducing queens of B. terrestris. We hypothesize that arrested ovary development in workers could be connected to suppressed IGF-1 expression, likely caused by the presence of the reproducing queen in the colony.

Males showed high values of Kr-h1 and relatively low Vg expression. As in workers, IIS is mediated by both investigated InRs and one ligand, LIRP, but not by IGF-1.

When comparing the expression patterns of all studied genes in tissues dissected from all castes, we found striking similarities between the fat body and hypopharyngeal glands. Therefore, we suggest that hypopharyngeal glands, an organ presumably intervening in digestion immediately after food intake, are subjected to similar hormonal control mechanisms as the ultimate storage organ, the fat body.

Author contributions

PJ, RH, and IV designed the study; PJ, UE, and AV acquired and analyzed data. PJ and UE drafted the manuscript, and all authors revised it, approved the final version, and agree to be accountable for the content of the work.

Conflict of interest statement

PJ, UE, RH, and IV declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. AV is an employee of Agricultural Research, Ltd., Troubsko, Czechia, a company that, among other activities, produces bumblebee colonies for pollination purposes. The reviewer DD declared a shared affiliation, though no other collaboration, with several of the authors PJ, UE, RH, IV to the handling Editor, who ensured that the process nevertheless met the standards of a fair and objective review.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the Czech Science Foundation (#14-04291S), Ministry of Education of the Czech Republic (#LD15102) and IOCB, CAS, Prague (RVO: 61388963). UE acknowledges funding by an IOCB postdoctoral fellowship.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AKH

adipokinetic hormone

- AKHR

AKH receptor

- CA

corpora allata

- CC

corpora cardiac

- Cp

crossing point

- EF1

elongation factor eEF-1 α

- FOXO

forkhead box protein O

- IGF-1

insulin growth factor 1

- IIS

insulin/insulin-like growth factor signaling

- ILP

insulin-like peptide

- InR

insulin-like receptor

- InR-1

insulin-like peptide receptor 1

- InR-2

insulin-like peptide receptor 2

- JH

juvenile hormone

- JHAMT

juvenile hormone acid methyltransferase

- Kr-h1

Krüppel homolog 1

- LIRP

locust insulin-related peptide

- MFE

methyl farnesoate epoxidase

- PLA2

phospholipase A2

- TOR

target of rapamycin

- Vg

vitellogenin.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fphys.2016.00574/full#supplementary-material

qRT-PCR primers and efficiencies used in this study.

ANOVA results for the ten genes investigated in this study.

Example of tissue samples used in the present study. The organs originated from a B. terrestris worker and represent: (A) Brain; (B) Hypopharyngeal glands; (C) Labial glands; (D) Flight muscles; (E) Gut: Crop (C), Ventriculus (V) and Rectum (R); (F) Gonads (Ovaries); and (G) Fat body.

The sequence analysis of insulin like peptide precursors. (A) The alignment of Bombus terrestris IGF-1 (XP_012166281.1) and LIRP (XP_003400778.1) with related sequences of Apis mellifera (ILP-1: XP_016769293.1; ILP-2:NP_001171374.1 - incomplete sequence with RefSeq status: PROVISIONAL) and Apis florea (IGF-1: XP_012338912.1; LIRP: XP_003690101.1). The human insulin growth factor (Homo sapiens IGF-1a: NP_000609.1) and Locusta migratoria LIRP (P15131.2) are included as original references. Conserved residues are boxed in black, identical sequences in dark gray, and similar sequences in light gray. (B) The percent sequence identities of all the aligned peptides are presented.

References

- Albert S., Spaethe J., Grübel K., Rössler W. (2014). Royal jelly-like protein localization reveals differences in hypopharyngeal glands buildup and conserved expression pattern in brains of bumblebees and honeybees. Biol. Open 3, 281–288. 10.1242/bio.20147211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amdam G. V., Omholt S. W. (2002). The regulatory anatomy of honeybee lifespan. J. Theor. Biol. 216, 209–228. 10.1006/jtbi.2002.2545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amdam G. V., Simões Z. L., Hagen A., Norberg K., Schrøder K., Mikkelsen Ø., et al. (2004). Hormonal control of the yolk precursor vitellogenin regulates immune function and longevity in honeybees. Exp. Gerontol. 39, 767–773. 10.1016/j.exger.2004.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ament S. A., Corona M., Pollock H. S., Robinson G. E. (2008). Insulin signaling is involved in the regulation of worker division of labor in honey bee colonies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 4226–4231. 10.1073/pnas.0800630105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsalem E., Galbraith D. A., Cnaani J., Teal P. E., Grozinger C. M. (2015b). Conservation and modification of genetic and physiological toolkits underpinning diapause in bumble bee queens. Mol. Ecol. 24, 5596–5615. 10.1111/mec.13410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsalem E., Grozinger C. M., Padilla M., Hefetz A. (2015a). The physiological and genomic bases of bumble bee social behaviour, in Advances in Insect Physiology, eds Amro Z., Clement F. K.(London: Academic Press; ), 37–93. [Google Scholar]

- Amsalem E., Malka O., Grozinger C., Hefetz A. (2014). Exploring the role of juvenile hormone and vitellogenin in reproduction and social behavior in bumble bees. BMC Evol. Biol. 14:45. 10.1186/1471-2148-14-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen C. L., Jensen J. L., Øntoft T. F. (2004). Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: a model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res. 64, 5245–5250. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonova Y., Arik A. J., Moore W., Riehle M. A., Brown M. R. (2012). Insulin-like peptides: structure, signaling, and function, in Insect Endocrinology, ed Gilbert L. I.(San Diego, CA: Academic Press; ), 63–92. [Google Scholar]

- Arrese E. L., Soulages J. L. (2010). Insect fat body: energy, metabolism, and regulation. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 55, 207–225. 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badisco L., Claeys I., Van Hiel M., Clynen E., Huybrechts J., Vandersmissen T., et al. (2008). Purification and characterization of an insulin-related peptide in the desert locust, Schistocerca gregaria: immunolocalization, cDNA cloning, transcript profiling and interaction with neuroparsin. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 40, 137–150. 10.1677/JME-07-0161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badisco L., Van Wielendaele P., Vanden Broeck J. (2013). Eat to reproduce: a key role for the insulin signaling pathway in adult insects. Front. Physiol. 4:202. 10.3389/fphys.2013.00202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajgar A., Jindra M., Dolezel D. (2013). Autonomous regulation of the insect gut by circadian genes acting downstream of juvenile hormone signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 4416–4421. 10.1073/pnas.1217060110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barchuk A. R., Bitondi M. M., Simões Z. L. (2002). Effects of juvenile hormone and ecdysone on the timing of vitellogenin appearance in hemolymph of queen and worker pupae of Apis mellifera. J. Insect Sci. 2:1. 10.1672/1536-2442(2002)002[0001:mfmicc]2.0.co;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beenakkers A. M. T., Van der Horst D. J., Van Marrewijk W. J. A. (1984). Insect flight muscle metabolism. Insect Biochem. 14, 243–260. 10.1016/0020-1790(84)90057-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bellés X., Martín D., Piulachs M.-D. (2005). The mevalonate pathway and the synthesis of juvenile hormone in insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 50, 181–199. 10.1146/annurev.ento.50.071803.130356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch G., Borst D. W., Huang Z., Robinson G. E., Cnaani J., Hefetz A. (2000). Juvenile hormone titers, juvenile hormone biosynthesis, ovarian development and social environment in Bombus terrestris. J. Insect Physiol. 46, 47–57. 10.1016/S0022-1910(99)00101-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodláková K., Jedlička P., Kodrík D. (2016). Adipokinetic hormones control amylase activity in the cockroach (Periplaneta americana) gut. Insect Sci.. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1111/1744-7917.12314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomtorin A. D., Mackert A., Rosa G. C., Moda L. M., Martins J. R., Bitondi M. M., et al. (2014). Juvenile hormone biosynthesis gene expression in the corpora allata of honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) female castes. PLoS ONE 9:e86923. 10.1371/journal.pone.0086923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogiolo W., Stocker H., Ikeya T., Rintelen F., Fernandez R., Hafen E. (2001). An evolutionarily conserved function of the Drosophila insulin receptor and insulin-like peptides in growth control. Curr. Biol. 11, 213–221. 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00068-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgan T. J., Carolan J. C., Bridgett S. J., Sumner S., Blaxter M. L., Brown M. J. (2011). Polyphenism in social insects: insights from a transcriptome-wide analysis of gene expression in the life stages of the key pollinator, Bombus terrestris. BMC Genom. 12:623. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonello-Frattini N. A., Guidugli-Lazzarini K. R., Simões Z. L., Hartfelder K. (2010). Mars is close to venus – Female reproductive proteins are expressed in the fat body and reproductive tract of honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) drones. J. Insect Physiol. 56, 1638–1644. 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2010.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona M., Libbrecht R., Wurm Y., Riba-Grognuz O., Studer R. A., Keller L. (2013). Vitellogenin underwent subfunctionalization to acquire caste and behavioral specific expression in the harvester ant Pogonomyrmex barbatus. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003730. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona M., Velarde R. A., Remolina S., Moran-Lauter A., Wang Y., Hughes K. A., et al. (2007). Vitellogenin, juvenile hormone, insulin signaling, and queen honey bee longevity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 7128–7133. 10.1073/pnas.0701909104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daimon T., Shinoda T. (2013). Function, diversity, and application of insect juvenile hormone epoxidases (CYP15). Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 60, 82–91. 10.1002/bab.1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallacqua R. P., Simões Z. L. P., Bitondi M. M. G. (2007). Vitellogenin gene expression in stingless bee workers differing in egg-laying behavior. Insectes Soc. 54, 70–76. 10.1007/s00040-007-0913-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Azevedo S. V., Hartfelder K. (2008). The insulin signaling pathway in honey bee (Apis mellifera) caste development — differential expression of insulin-like peptides and insulin receptors in queen and worker larvae. J. Insect Physiol. 54, 1064–1071. 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2008.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Loof A., Boerjan B., Ernst U. R., Schoofs L. (2013). The mode of action of juvenile hormone and ecdysone: towards an epi-endocrinological paradigm? Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 188, 35–45. 10.1016/j.ygcen.2013.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchateau M. J., Velthuis H. H. W. (1988). Development and reproductive strategies in Bombus terrestris colonies. Behaviour 107, 186–207. 10.1163/156853988X00340 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duchateau M. J., Velthuis H. H. W. (1989). Ovarian development and egg laying in workers of Bombus terrestris. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 51, 199–213. 10.1111/j.1570-7458.1989.tb01231.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gäde G. (2009). Peptides of the adipokinetic hormone/red pigment-concentrating hormone family. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1163, 125–136. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03625.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gäde G., Auerswald L. (2003). Mode of action of neuropeptides from the adipokinetic hormone family. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 132, 10–20. 10.1016/S0016-6480(03)00159-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman W. G., Cusson M. (2012). The juvenile hormones, in Insect Endocrinology, ed Gilbert L. I.(Elsevier; ), 310–365. [Google Scholar]

- Goulson D. (2010). Bumblebees: Behaviour, Ecology, and Conservation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guidugli K. R., Nascimento A. M., Amdam G. V., Barchuk A. R., Omholt S., Simões Z. L. P., et al. (2005a). Vitellogenin regulates hormonal dynamics in the worker caste of a eusocial insect. FEBS Lett. 579, 4961–4965. 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidugli K. R., Piulachs M.-D., Bellés X., Lourenço A. P., Simões Z. L. P. (2005b). Vitellogenin expression in queen ovaries and in larvae of both sexes of Apis mellifera. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 59, 211–218. 10.1002/arch.20061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton W. D. (1963). The evolution of altruistic behavior. Am. Nat. 97, 354–356. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison M. C., Hammond R. L., Mallon E. B. (2015). Reproductive workers show queenlike gene expression in an intermediately eusocial insect, the buff-tailed bumble bee Bombus terrestris. Mol. Ecol. 24, 3043–3063. 10.1111/mec.13215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartfelder K., Emlen D. J. (2012). Endocrine control of insect polyphenism, in Insect Endocrinology, ed Gilbert L. I.(San Diego, CA: Academic Press; ), 464–522. [Google Scholar]

- Havukainen H., Münch D., Baumann A., Zhong S., Halskau Ø., Krogsgaard M., et al. (2013). Vitellogenin recognizes cell damage through membrane binding and shields living cells from reactive oxygen species. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 28369–28381. 10.1074/jbc.M113.465021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornáková D., Matoušková P., Kindl J., Valterová I., Pichová I. (2010). Selection of reference genes for real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis in tissues from Bombus terrestris and Bombus lucorum of different ages. Anal. Biochem. 397, 118–120. 10.1016/j.ab.2009.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt J. H., Amdam G. V. (2005). Bivoltinism as an antecedent to eusociality in the paper wasp genus Polistes. Science 308, 264–267. 10.1126/science.1109724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt J. H., Kensinger B. J., Kossuth J. A., Henshaw M. T., Norberg K., Wolschin F., et al. (2007). A diapause pathway underlies the gyne phenotype in Polistes wasps, revealing an evolutionary route to caste-containing insect societies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 14020–14025. 10.1073/pnas.0705660104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedličková V., Jedlička P., Lee H.-J. (2015). Characterization and expression analysis of adipokinetic hormone and its receptor in eusocial aphid Pseudoregma bambucicola. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 223, 38–46. 10.1016/j.ygcen.2015.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jindra M., Palli S. R., Riddiford L. M. (2013). The juvenile hormone signaling pathway in insect development. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 58, 181–204. 10.1146/annurev-ento-120811-153700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapheim K. M., Pan H., Li C., Salzberg S. L., Puiu D., Magoc T., et al. (2015). Genomic signatures of evolutionary transitions from solitary to group living. Science 348, 1139–1143. 10.1126/science.aaa4788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B.-G., Shim J.-K., Kim D.-W., Kwon Y. J., Lee K.-Y. (2008). Tissue-specific variation of heat shock protein gene expression in relation to diapause in the bumblebee Bombus terrestris. Entomol. Res. 38, 10–16. 10.1111/j.1748-5967.2008.00142.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. K., Rulifson E. J. (2004). Conserved mechanisms of glucose sensing and regulation by Drosophila corpora cardiaca cells. Nature 431, 316–320. 10.1038/nature02897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.-J., Hwang J.-S., Yoon H.-J., Yun E.-Y., Lee S. B., Ahn M.-Y., et al. (2006). Expressed sequence tag analysis of the diapausing queen of the bumblebee Bombus ignitus. Entomol. Res. 36, 191–195. 10.1111/j.1748-5967.2006.00033.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kodrík D., Stašková T., Jedličková V., Weyda F., Závodská R., Pflegerová J. (2015). Molecular characterization, tissue distribution, and ultrastructural localization of adipokinetic hormones in the CNS of the firebug Pyrrhocoris apterus (Heteroptera, Insecta). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 210, 1–11. 10.1016/j.ygcen.2014.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama T., Mendes C. C., Mirth C. K. (2013). Mechanisms regulating nutrition-dependent developmental plasticity through organ-specific effects in insects. Front. Physiol. 4:263. 10.3389/fphys.2013.00263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupke J., Spaethe J., Mueller M. J., Rössler W., Albert Š. (2012). Molecular and biochemical characterization of the major royal jelly protein in bumblebees suggest a non-nutritive function. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 42, 647–654. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2012.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Huang J., Cai W., Zhao Z., Peng W., Wu J. (2010). The vitellogenin of the bumblebee, Bombus hypocrita: studies on structural analysis of the cDNA and expression of the mRNA. J. Comp. Physiol. B 180, 161–170. 10.1007/s00360-009-0434-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libbrecht R., Corona M., Wende F., Azevedo D. O., Serrão J. E., Keller L. (2013). Interplay between insulin signaling, juvenile hormone, and vitellogenin regulates maternal effects on polyphenism in ants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 11050–11055. 10.1073/pnas.1221781110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz M. W., Kellner R., Völkl W., Hoffmann K. H., Woodring J. (2001). A comparative study on hypertrehalosaemic hormones in the Hymenoptera: sequence determination, physiological actions and biological significance. J. Insect Physiol. 47, 563–571. 10.1016/S0022-1910(00)00133-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz M. W., Kellner R., Woodring J., Hoffmann K. H., Gäde G. (1999). Hypertrehalosaemic peptides in the honeybee (Apis mellifera): purification, identification and function. J. Insect Physiol. 45, 647–653. 10.1016/S0022-1910(98)00158-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H. L., Pietrantonio P. V. (2011). Insect insulin receptors: insights from sequence and caste expression analyses of two cloned hymenopteran insulin receptor cDNAs from the fire ant. Insect Mol. Biol. 20, 637–649. 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2011.01094.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden T. (2003). The BLAST sequence analysis tool, in National Center for Biotechnology Information (Bethesda, MD: ). [Google Scholar]

- Morandin C., Havukainen H., Kulmuni J., Dhaygude K., Trontti K., Helanterä H. (2014). Not only for egg yolk – functional and evolutionary insights from expression, selection, and structural analyses of Formica ant vitellogenins. Mol. Biol. Evol. 31, 2181–2193. 10.1093/molbev/msu171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münch D., Ihle K. E., Salmela H., Amdam G. V. (2015). Vitellogenin in the honey bee brain: atypical localization of a reproductive protein that promotes longevity. Exp. Gerontol. 71, 103–108. 10.1016/j.exger.2015.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutti N. S., Dolezal A. G., Wolschin F., Mutti J. S., Gill K. S., Amdam G. V. (2011). IRS and TOR nutrient-signaling pathways act via juvenile hormone to influence honey bee caste fate. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 3977–3984. 10.1242/jeb.061499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu D., Zheng H., Corona M., Lu Y., Chen X., Cao L., et al. (2014). Transcriptome comparison between inactivated and activated ovaries of the honey bee Apis mellifera L. Insect Mol. Biol. 23, 668–681. 10.1111/imb.12114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto N., Yamanaka N., Yagi Y., Nishida Y., Kataoka H., O'Connor M. B., et al. (2009). A fat body-derived IGF-like peptide regulates postfeeding growth in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 17, 885–891. 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennisi E. (2005). How did cooperative behavior evolve? Science 309:93. 10.1126/science.309.5731.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereboom J. J. M. (2000). The composition of larval food and the significance of exocrine secretions in the bumblebee Bombus terrestris. Insectes Soc. 47, 11–20. 10.1007/s000400050003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl M. W. (2001). A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:e45. 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2011.0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piulachs M. D., Guidugli K. R., Barchuk A. R., Cruz J., Simões Z. L., Bellés X. (2003). The vitellogenin of the honey bee, Apis mellifera: structural analysis of the cDNA and expression studies. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 33, 459–465. 10.1016/S0965-1748(03)00021-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig O., Tjian R. (2005). Transcriptional feedback control of insulin receptor by dFOXO/FOXO1. Genes Dev. 19, 2435–2446. 10.1101/gad.1340505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R. Development Core Team (2015). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Available online at: http://www.R-project.org [Google Scholar]

- Reiff T., Jacobson J., Cognigni P., Antonello Z., Ballesta E., Tan K. J., et al. (2015). Endocrine remodelling of the adult intestine sustains reproduction in Drosophila. eLife 4:e06930. 10.7554/eLife.06930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddiford L. M. (2012). How does juvenile hormone control insect metamorphosis and reproduction? Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 179, 477–484. 10.1016/j.ygcen.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson G. E., Grozinger C. M., Whitfield C. W. (2005). Sociogenomics: social life in molecular terms. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 257–270. 10.1038/nrg1575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Zokan E. M., Cunningham C. B., Hebb L. E., McKinney E. C., Moore A. J. (2015). Vitellogenin and vitellogenin receptor gene expression is associated with male and female parenting in a subsocial insect. Proc. R. Soc. B 282:20150787. 10.1098/rspb.2015.0787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadd B. M., Barribeau S. M., Bloch G., de Graaf D. C., Dearden P., Elsik C. G., et al. (2015). The genomes of two key bumblebee species with primitive eusocial organization. Genome Biol. 16, 1–32. 10.1186/s13059-015-0623-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmela H., Stark T., Stucki D., Fuchs S., Freitak D., Dey A., et al. (2016). Ancient duplications have led to functional divergence of vitellogenin-like genes potentially involved in inflammation and oxidative stress in honey bees. Genome Biol. Evol. 8, 495–506. 10.1093/gbe/evw014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sappington T. W., Raikhel A. S. (1998). Molecular characteristics of insect vitellogenins and vitellogenin receptors. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 28, 277–300. 10.1016/S0965-1748(97)00110-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seehuus S.-C., Norberg K., Krekling T., Fondrk K., Amdam G. V. (2007). Immunogold localization of vitellogenin in the ovaries, hypopharyngeal glands and head fat bodies of honeybee workers, Apis mellifera. J. Insect Sci. 7, 1–14. 10.1673/031.007.5201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpigler H. Y., Siegel A. J., Huang Z. Y., Bloch G. (2016). No effect of juvenile hormone on task performance in a bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) supports an evolutionary link between endocrine signaling and social complexity. Horm. Behav. 85, 67–75. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2016.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpigler H., Amsalem E., Huang Z. Y., Cohen M., Siegel A. J., Hefetz A., et al. (2014). Gonadotropic and physiological functions of juvenile hormone in bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) workers. PLoS ONE 9:e100650. 10.1371/journal.pone.0100650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpigler H., Patch H. M., Cohen M., Fan Y., Grozinger C. M., Bloch G. (2010). The transcription factor Krüppel homolog 1 is linked to hormone mediated social organization in bees. BMC Evol. Biol. 10:120. 10.1186/1471-2148-10-120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim C., Denlinger D. L. (2013). Insulin signaling and the regulation of insect diapause. Front. Physiol. 4:189. 10.3389/fphys.2013.00189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simola D. F., Wissler L., Donahue G., Waterhouse R. M., Helmkampf M., Roux J., et al. (2013). Social insect genomes exhibit dramatic evolution in gene composition and regulation while preserving regulatory features linked to sociality. Genome Res. 23, 1235–1247. 10.1101/gr.155408.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šobotník J., Kalinová B., Cahlíková L., Weyda F., Ptáček V., Valterová I. (2008). Age-dependent changes in structure and function of the male labial gland in Bombus terrestris. J. Insect Physiol. 54, 204–214. 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2007.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socha R., Kodrík D. (1999). Differences in adipokinetic response of Pyrrhocoris apterus (Heteroptera) in relation to wing dimorphism and diapause. Physiol. Entomol. 24, 278–284. 10.1046/j.1365-3032.1999.00143.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sparagana S. P., Bhaskaran G., Barrera P. (1985). Juvenile hormone acid methyltransferase activity in imaginal discs of Manduca sexta prepupae. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2, 191–202. 10.1002/arch.940020207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C., Zhang S. (2015). Immune-relevant and antioxidant activities of vitellogenin and yolk proteins in fish. Nutrients 7, 8818–8829. 10.3390/nu7105432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth A. L., Varala K., Newman T. C., Miguez F. E., Hutchison S. K., Willoughby D. A., et al. (2007). Wasp gene expression supports an evolutionary link between maternal behavior and eusociality. Science 318, 441–444. 10.1126/science.1146647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vafopoulou X. (2014). The coming of age of insulin-signaling in insects. Front. Physiol. 5:216. 10.3389/fphys.2014.00216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valle D. (1993). Vitellogenesis in insects and other groups: a review. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 88, 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Horst D. J.. (2003). Insect adipokinetic hormones: release and integration of flight energy metabolism. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 136, 217–226. 10.1016/S1096-4959(03)00151-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargo E. L., Laurel M. (1994). Studies on the mode of action of a queen primer pheromone of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. J. Insect Physiol. 40, 601–610. 10.1016/0022-1910(94)90147-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra J. A., Rodriguez L., Weaver R. J. (2012). Allatotropin, leucokinin and AKH in honey bees and other Hymenoptera. Peptides 35, 122–130. 10.1016/j.peptides.2012.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal K. J., Kumar D. (2000). Role of juvenile hormone in the synthesis and sequestration of vitellogenins in the red cotton stainer, Dysdercus koenigii (Heteroptera: Pyrrhocoridae). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharrmacol. 127, 153–163. 10.1016/S0742-8413(00)0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verlinden H., Lismont E., Bil M., Urlacher E., Mercer A., Vanden Broeck J., et al. (2013). Characterisation of a functional allatotropin receptor in the bumblebee, Bombus terrestris (Hymenoptera, Apidae). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 193, 193–200. 10.1016/j.ygcen.2013.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Brent C. S., Fennern E., Amdam G. V. (2012). Gustatory perception and fat body energy metabolism are jointly affected by vitellogenin and juvenile hormone in honey bees. PLoS Genet. 8:e1002779. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnes G. R., Bolker B., Bonebakker L., Gentleman R., Liaw W. H. A., Lumley T. (2015). gplots: Various R Programming Tools for Plotting Data. Available online at: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package = gplots

- Weil T., Korb J., Rehli M. (2009). Comparison of queen-specific gene expression in related lower termite species. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 1841–1850. 10.1093/molbev/msp095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodard S. H., Bloch G. M., Band M. R., Robinson G. E. (2014). Molecular heterochrony and the evolution of sociality in bumblebees (Bombus terrestris). Proc. R. Soc. B 281:20132419. 10.1098/rspb.2013.2419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodard S. H., Fischman B. J., Venkat A., Hudson M. E., Varala K., Cameron S. A., et al. (2011). Genes involved in convergent evolution of eusociality in bees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 7472–7477. 10.1073/pnas.1103457108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodring J., Hoffmann K. H., Lorenz M. W. (2003). Identification and function of the hypotrehalosaemic hormone (Mas-AKH) in workers, drones and queens of Apis mellifera ligustica and A. m. carnica. J. Apicult. Res. 42, 4–8. 10.1080/00218839.2003.11101078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]