Abstract

Objectives

The relationship between cancer and thrombosis was first recognized by the French internist Armand Trousseau in 1865. Trousseau's syndrome is a spectrum of symptoms that result from recurrent thromboembolism associated with cancer or malignancy-related hypercoagulability. In this study, we investigated whether demographics, clinical features, or laboratory findings were able to predict recurrent stroke episodes in patients with Trousseau's syndrome.

Methods

In total, 178 adult patients were enrolled in this retrospective cross-sectional study. All patients had been admitted to the emergency room of our hospital between January 2011 and September 2014 and were diagnosed with acute ischemic stroke. Patients were divided into two groups: patients with malignancy (Trousseau's syndrome), and patients without malignancy.

Results

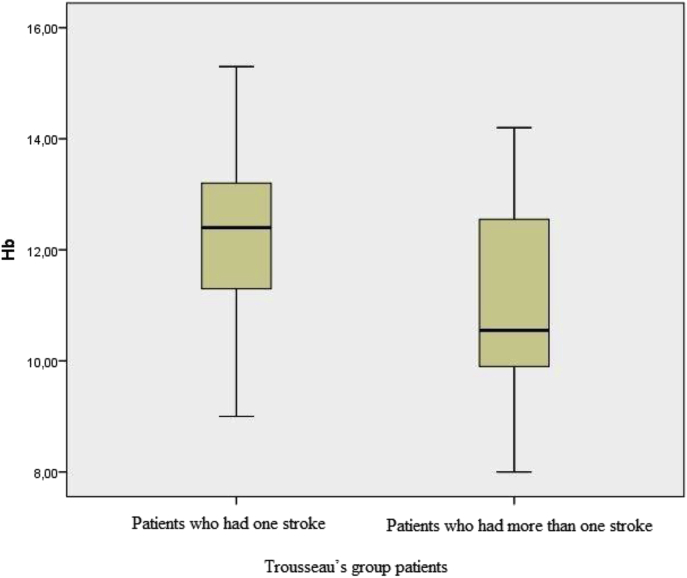

There were several significant differences between the laboratory results of the two patient groups. For patients with Trousseau's, the hemoglobin levels for those with one stroke was 12.29 ± 1.81, while those in patients who had experienced more than one stroke was 10.94 ± 2.14 (p = 0.004).

Conclusions

Trousseau's syndrome is a cancer-associated coagulopathy associated with high morbidity and mortality rates. In this study, anemia was associated with increased stroke recurrence in patients with malignancy (Trousseau's syndrome).

Keywords: Anemia, Ischemic stroke, Malignancy, Trousseau's syndrome

1. Introduction

Among the neurological diseases, cerebrovascular diseases are the most common in developed countries. Stroke is the most common cause of death in these countries, and neoplastic diseases (cancer and hematologic tumors) are the second most common cause. However, stroke is a rare complication of cancer therapy, and does not occur as often as metastasis or neurotoxicity.1, 2

A retrospective autopsy study of a large cohort of cancer patients performed by Graus et al showed that 15% of cancer patients have evidence of cerebrovascular disease, and about half of these patients have clinical symptoms of stroke.3

In this study, we retrospectively analyzed the demographic, clinical, and laboratory data of cancer and cancer-free patients that presented with acute ischemic stroke in the emergency department.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study population

A retrospective cross-sectional study including 178 adult patients was carried out after taking approval from institutional ethics committee. We retrospectively investigated patients who were admitted to our emergency department (ED) with ischemic stroke between January 1st, 2011 and July 15th, 2014. Medical history and physical examination data were obtained from all patients who were diagnosed with acute ischemic stroke. Acute ischemic stroke diagnoses were confirmed by further imaging tests of the brain, including computed tomography (CT) and diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DW-MRI).

The ischemic stroke patients were divided into two groups: group 1; patients with active cancer (Trousseau's) and group 2; those without. Active cancer was defined as a confirmed malignancy, which was either treated or untreated in the six months before stroke.4 Demographic characteristics and clinical data were collected and evaluated. These two groups were then divided into subgroups: those who had had one stroke (groups 1A and 2A) and those who had more than one (groups 1B and 2B). Patients who were diagnosed with transient ischemia or who had no evidence of either acute or chronic infarction after neuroimaging were excluded from the study. Patients with primary brain cancer and patients who had intracranial metastases were also excluded since these patients were thought to have different underlying stroke mechanisms.

2.2. Statistical analysis

All data was analyzed using SPSS software (version 15.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The chi-square test was used to compare stroke risk factors and subtypes between cancer patients who had experienced one ischemic stroke and those who had experienced more than one. A student's t-test was used to compare biomarkers between the two groups. P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Among the 200 adult patients referred to the ED with stroke, we identified 178 patients who were diagnosed as acute ischemic stroke. Nine patients with transient ischemia, eight patients with primary brain cancer and five patients who had intracranial metastases were excluded from the study. The active cancer group (group 1) included 91 patients (60 male, 31 female), and the stroke without cancer group (group 2) included 87 (56 male, 31 female). The mean age was 65.18 ± 11.98 among those with cancer and 62.80 ± 12.23 among those without; this difference was not significant (p = 0.193). Among the patients with active cancer, 24 had previously experienced a stroke whereas in the group without cancer, 15 had previously experienced a stroke. The demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of ischemic stroke patients with malignancy (group 1) versus those with no malignancy (group 2).

| Group 1 (n = 91) | Group 2 (n = 87) | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65.18 ± 11.98 | 62.80 ± 1 2.23 | 0.193 |

| Gender (Female/Male) | 31/60 | 31/56 | 0.828 |

| Smoking | 64 | 52 | |

| Drinking | 44 | 21 | |

| Previous stroke history | 24 | 15 | |

| Hypertension | 50 | 59 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 27 | 36 | |

| CAD | 40 | 32 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 18 | 4 | |

| COPD | 11 | 7 | |

| CHF | 9 | 1 | |

| Liver Cirrhosis | 5 | – | |

| CRF | 3 | 1 |

Group 1, the ischemic stroke patients with malignancy (trousseau group); Group 2, the ischemic stroke patients with no malignancy; CAD, coronary arterial disease; COPD, chronical obstructive pulmonary disease; CHF, chronical heart failure; CRF, chronical renal failure.

Student's t-test.

Laboratory tests, including blood urine nitrogen, creatinine, aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, hematocrit, D-dimer, C-reactive protein, hemoglobin, and platelet counts, were obtained for all patients, and significant differences were found between groups for all parameters (p < 0.05). The patients' laboratory values are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Laboratory values of ischemic stroke patients with malignancy (group 1) and those patients with no malignancy (group 2) at the time of presentation.

| Parameters | Group 1 (n = 91) | Group 2 (n = 87) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| BUN (mg/dl) | 25.19 ± 14.29 | 18.05 ± 7.01 | <0.001 |

| Cre (mg/dl) | 1.02 ± 0.47 | 0.90 ± 0.30 | 0.034 |

| AST (U/L) | (13–584) | (9–88) | 0.004 |

| ALT (U/L) | (6–236) | (6–71) | 0.001 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 36.24 ± 5.84 | 41.20 ± 5.20 | <0.001 |

| D.dimer (ug FEU/ml) | (0.10–11.55) | (0.10–8.70) | <0.001 |

| CRP (mg/dl) | (0.10–27.60) | (0.10–14.40) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 11.93 ± 1.98 | 13.61 ± 1.92 | <0.001 |

| Platelets (×103μL) | 262.58 ± 107.45 | 233.25 ± 66.35 | <0.001 |

Group 1, the ischemic stroke patients with malignancy (trousseau group); Group 2, the ischemic stroke patients with no malignancy. BUN, blood urine nitrogene; Cre, creatinine; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase; CRP, c-reactive protein.

Student's t-test.

Patients with active cancer were divided into two subgroups based on the number of strokes experienced after malignancy diagnosis: only one stroke (n = 67; group 1A) or more than one (n = 24; group 1B) were. Hemoglobin and hematocrit levels were significantly greater among patients who had only one stroke: hemoglobin, 12.29 ± 1.81 vs. 10.94 ± 2.00 (p = 0.004, Fig. 1) and hematocrit, 37.15 ± 5.34 vs. 33.70 ± 6.51 (p = 0.012). Laboratory values for the two subgroups are shown in Table 3.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of hemoglobin levels (median (interquartile range)) between Trousseau's group patients who had one stroke (group 1A) and those patients who had more than one stroke (group 1B) at the time of presentation.

Table 3.

Laboratory values of trousseau group patients who had one stroke (group 1A) and those patients who had more than one stroke (group 1B) at the time of presentation.

| Parameters | Group 1A (n = 67) | Group 1B (n = 24) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| BUN (mg/dl) | 25.43 ± 14.46 | 24.50 ± 14.08 | 0.785 |

| Cre (mg/dl) | 1.04 ± 0.49 | 0.98 ± 0.41 | 0.564 |

| AST (U/L) | (14–584) | (13–78) | 0.346 |

| ALT (U/L) | (7–236) | (6–145) | 0.732 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 37.15 ± 5.34 | 33.70 ± 6.51 | 0.012 |

| D-dimer (ug FEU/ml) | (0.10–8.10) | (0.30–8.70) | 0.445 |

| CRP (mg/dl) | (0.10–27.60) | (0.20–26.80) | 0.534 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 12.29 ± 1.81 | 10.94 ± 2.14 | 0.004 |

| Platelets (×103 μL) | 255.92 ± 96.70 | 281.17 ± 133.66 | 0.326 |

Group 1A, consisted of trousseau group patients who had one stroke; Group 2B, consisted of trousseau group patients who had more than one stroke. BUN, blood urine nitrogene; Cre, creatinine; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase; CRP, c-reactive protein.

Chi-square test.

Among patients without cancer, laboratory values did not differ between those who had experienced only one stroke (n = 72; group 2A) and those who had multiple strokes (n = 15; group 2B) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Laboratory values of cancer-free patients who suffered their first stroke (group 2A) and those patients who suffered recurrent stroke (group 2B) at the time of presentation.

| Parameters | Group 2A (n = 72) | Group 2B (n = 15) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| BUN (mg/dl) | 17.85 ± 6.84 | 19.06 ± 7.97 | 0.545 |

| Cre (mg/dl) | 0.90 ± 0.32 | 0.87 ± 0.15 | 0.706 |

| AST (U/L) | 23.10 ± 10.74 | 23.20 ± 6.04 | 0.972 |

| ALT (U/L) | 21.79 ± 11.75 | 22.40 ± 9.37 | 0.851 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 41.69 ± 5.16 | 38.89 ± 4.90 | 0.058 |

| D.dimer (ug FEU/ml) | (0.10–11.55) | (0.10–14.40) | 0.649 |

| CRP (mg/dl) | (0.30–1.60) | (0.20–3.90) | 0.874 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 13.77 ± 1.87 | 12.83 ± 2.00 | 0.084 |

| Platelets (×103 μL) | 230.05 ± 64.38 | 249.73 ± 75.41 | 0.299 |

Group 2A, consisted of ischemic stroke patients who had one stroke; Group 2B, consisted of ischemic stroke patients who had more than one stroke. BUN, blood urine nitrogene; Cre, creatinine; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase; CRP, c-reactive protein.

Chi-square test.

Among patients with cancer, 21 patients were diagnosed with prostate cancer, 14 with lung cancer, 11 with gastric cancer, and nine with skin cancer (Table 5).

Table 5.

Types of cancer in ischemic stroke patients with malignancy (Traussea's group).

| Cancer type | Patient numbers and percentages (n = 91) (%) |

|---|---|

| Prostate cancer | 21 (23.08%) |

| Lung cancer | 14 (15.38%) |

| Skin cancer | 9 (9.89%) |

| Gastric cancer | 11 (12.09%) |

| Colon cancer | 6 (6.59%) |

| Lymphoma | 4 (4.39%) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 5 (5.49%) |

| Breast cancer | 5 (5.49%) |

| Renal cancer | 5 (5.49%) |

| Cervix cancer | 3 (3.31%) |

| Pancreatic cancer | 3 (3.31%) |

| Others | 5 (5.49%) |

4. Discussion

Kim et al5 reported that d-dimer, pro-BNP, and fibrinogen levels were higher in ischemic stroke patients with cancer compared to those without. Consistent with the literature,5 d-dimer levels in the present study were significantly higher in cancer patients. These results imply a relationship between cancer and inflammation, thrombus formation, and coagulopathy, which could explain the increased frequency of ischemic stroke in cancer patients compared with non-cancer patients.5

Kim et al found that among stroke patients with cancer, 33 (21.2%) had gastric cancer, 25 (16%) had lung cancer, 22 (14.1%) had colon cancer, 20 (12.8%) had hepatobiliary cancer, and 84 (53.8%) had metastases.4 In the present study, 21 patients were diagnosed with prostate cancer (23.08%), 14 with lung cancer (15.38%), 11 with gastric cancer (12.09%), and 9 with skin cancer (9.89%).

C-reactive protein is an acute peptide related to inflammation and the progression of hemangioendothelioma, and increases during systemic inflammation and atherosclerotic disease.6 Previous studies showed that leukocyte count and levels of fibrinogen and C-reactive protein (CRP) may serve as markers of inflammatory activity. Inflammatory activity increases the risk for vascular events and worsens prognosis after a stroke.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 In the present study, CRP levels were 0.10–27.60 Unit (U) acute ischemic stroke patients with malignancy (Trousseau's syndrome), and 0.10–14.40 U in stroke patients with no malignancy, a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001).

Among the hematopoietic growth factors, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) are frequently used in oncology due to their ability to correct chemotherapy-induced bone marrow suppression and anemia; however, administration of ESAs to patients with cancer is associated with increased risks for venous thromboembolism, higher mortality,16, 17 and even tumor progression.18 In the present study, hemoglobin levels were 11.93 ± 1.98 in stroke patients with malignancy (Trousseau's syndrome), and 13.61 ± 1.92 in stroke patients without, also a significant difference (p < 0.001). Thus, in patients with malignancies, stroke is strongly associated with anemia. In our study, among the subgroups, hemoglobin levels were 12.29 ± 1.81 for the patients who had experienced only one stroke, and 10.94 ± 2.14 for the patients who had experienced multiple strokes, and again, these values were significantly different (p = 0.004). This data suggests that there is a strong correlation between increased number of strokes and degree of anemia.

Smoking is a common risk factor in both ischemic stroke and cancer, and is also the cause of most ischemic strokes in cancer patients.2, 11 Most reports have found that hypertension and smoking are the most common causes of ischemic stroke in cancer patients,11, 12, 13, 14, 15 and these results correlate well with our findings. In our study, there was a higher incidence of both smoking and hypertension among Trousseau's patients (n = 64, 70.32%; n = 50, 54.94%, respectively).

5. Limitations

One limitation of this presented cross-sectional, retrospective analysis is that the sample is small and the other is that the study design limits the degree of change in anemia which may have led to recurrence of ischemic stroke in patients with Trousseau's syndrome. This issue in limitation should be considered in case-control studies with larger sample size.

6. Conclusions

In this preliminary study, we observed that repeated episodes of stroke in patients with Trousseau's syndrome seem to occur more frequently in the presence of anemia. Therefore, we suggest that restoration of hemoglobin levels may help prevent recurrent stroke in patients with Trousseau's syndrome.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of The Emergency Medicine Association of Turkey

References

- 1.Donati M.B. Thrombosis and cancer: trousseau syndrome revisited. Best Practice&Research Clin Haematol. 2009;22:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clouston P.D., DeAngelis L.M., Posner J.B. The spectrum of neurological disease in patients with systemic cancer. Ann Neurol. 2006;31:268–273. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graus F., Rogers L.R., Posner J.B. Cerebrovascular complications in patients with cancer. Med Baltim. 1985;64:16–35. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwarzbach C.J., Schaefer A., Ebert A. Stroke and cancer: the importance of cancer-associated hypercoagulation as a possible stroke etiology. Stroke. 2012;43:3029–3034. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.658625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim K., Lee J.H. Risk factors and biomarkers of ischemic stroke in cancer patients. J Stroke. 2014;16:91–96. doi: 10.5853/jos.2014.16.2.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pasceri V., Willerson J.T., Yeh E.T. Direct proinflammatory effect of C-reactive protein on human endothelial cells. Circulation. 2000;102:2165–2168. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.18.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gillum R.F., Mussolino M.E., Makuc D.M. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and coronary heartdisease: the NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48:353–361. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00156-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chamorro A., Vila N., Ascaso C. Early prediction of stroke severity. Role of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Stroke. 1995;26:573–576. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.4.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balestrino M., Partinico D., Finocchi C. White blood cell count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate correlate without come in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 1998;7:139–144. doi: 10.1016/s1052-3057(98)80141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eikelboom J.W., Hankey G.J., Baker R.I. C-reactive protein in ischemic stroke and its etiologic subtypes. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;12:74–81. doi: 10.1053/jscd.2003.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muir K.W., Weir C.J., Alwan W. C-reactive protein and outcome after ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1999;30:981–985. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.5.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turaj W., Slowik A., Dziedzic T. Increased plasma fibrinogen predicts one-year mortality in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J NeurolSci. 2006;246:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bots M.L., Elwood P.C., Salonen J.T. Level of fibrinogen and risk of fatal and nonfatal stroke. EUROSTROKE: a collaborative study among research centers in Europe. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56:14–18. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.suppl_1.i14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothwell P.M., Howard S.C., Power D.A. Fibrinogen concentration and risk of ischemic stroke and acute coronary events in 5113 patients with transient ischemic attack and minor ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2004;35:2300–2305. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000141701.36371.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alvarez-Perez F.J., Castelo-Branco M., Alvarez-Sabin J. Usefulness of measurement of fibrinogen, D-dimer, D-dimer/fibrinogen ratio, C reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate to assess the pathophysiology and mechanism of ischaemic stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:986–992. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.230870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett C.L., Silver S.M., Djulbegovic B. Venous thromboembolism and mortality associated with recombinant erythropoietin and darbepoetin administration for the treatment of cancer-associated anemia. JAMA. 2008;299:914–924. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.8.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bohlius J., Wilson J., Seidenfeld J. Recombinant human erythropoietins and cancer patients: updated meta-analysis of 57 studies including 9353 patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:708–714. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aapro M., Jelkmann W., Constantinescu S.N. Effects of erythropoietin receptors and erythropoiesis stimulating agents on disease progression in cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1249–1258. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]