Abstract

Mucopolysaccharidosis type VI or Maroteaux–Lamy syndrome is an autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disorder caused by deficiency of arylsulfatase B (ARS-B) enzyme activity. It results in mild to severe multi-organ system failure from accumulation of undigested glycosaminoglycans (GAGs); dermatan sulfate and chondroitin-4-sulfate. We have developed a single-step enzyme assay using a fluorescent substrate and dried blood spots to measure ARS-B activity to identify disease patients. This assay is robust, reproducible, specific and convenient to perform.

Abbreviations: 4-MU, 4-methylumbelliferone; 4-MUS, 4-methylumbelliferyl sulfate salt; ARS-B, arylsulfatase B; DBS, dried-blood spot; GAG, glycosaminoglycan; LSD, lysosomal storage disease; MPS VI, mucopolysaccharidosis type VI

Keywords: Dried blood spots, Mucopolysaccharidosis, Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome, Fluorometric enzyme assay

1. Introduction

Mucopolysaccharidosis type VI (MPS VI) is an autosomal recessive, hereditary lysosomal storage disorder (LSD) caused by a deficiency in arylsulfatase B (ARS-B; N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase) enzyme activity. This condition, also known as Maroteaux–Lamy syndrome, results in the progressive accumulation of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), especially dermatan and chondroitin sulfates in lysosomes that cause mild to severe symptoms including skeletal and joint deformities, enlarged spleen and liver, growth deceleration and death [1]. Swift and early confirmatory diagnosis is crucial to prevent serious irreversible damage, particularly since enzyme replacement therapy with galsulfase (Naglazyme) has shown significant retardation of symptoms [2], [3], [4], [5]. Existing methodology for diagnosis includes analysis of lysosomal GAGs in urine and enzyme activity measurements in blood leukocytes and fibroblast cultures, followed by mutational analysis [6], [7]. We have previously developed fluorometric microtiter plate-based bench top DBS assays for MPS I and II [8], [9]. These assays are robust, accurate and have a rapid turn-around time, thus reducing the time for diagnosis. Here we describe the development and validation of a similar fluorometric DBS assay to identify MPS VI.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents and solutions

Sodium acetate (anhydrous), lead acetate trihydrate, sodium hydroxide, glacial acetic acid, glycine, 4-methylumbelliferyl sulfate (4-MUS), 4-methylumbelliferone sodium salt (4-MU) and Corning 96-well-black, flat-bottom, microtiter plates were all obtained from Sigma Aldrich Corp. (St. Louis, MO). Molecular biology grade water was obtained from VWR International (Radnor, PA).

Stock buffer solution of 50 mmol/L sodium acetate was prepared and stored at 4 °C after adjusting pH to 5.0 with 2 M acetic acid solution. Substrate solution and extraction buffer were prepared using this stock solution. Briefly, 4-MUS was dissolved to 10 mmol/L in sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0), and stored at − 20 °C in 1 mL aliquots. Extraction buffer stock was prepared by dissolving lead acetate trihydrate in 50 mmol/L sodium acetate to a concentration of 15 mmol/L. This buffer stock was further diluted in water to a final concentration of 6 mmol/L lead acetate in 20 mmol/L sodium acetate for extracting the enzyme from the DBS. Stop buffer stock was prepared by dissolving glycine in water to a final concentration of 0.5 mol/L with pH adjusted to 10.3 using 1 M sodium hydroxide. This 0.5 mol/L glycine-sodium hydroxide stock was diluted in molecular biology grade water to a final concentration of 85 mmol/L, to provide the working stop buffer for terminating the enzyme reaction.

2.2. Blood spots and assay setup

De-identified dried blood spots (n = 78) obtained from the Duke Biochemical Genetics Laboratory (BGL) were used to establish the normal range for ARS-B enzyme activity. MPS VI patient DBS (n = 10), diagnosed through leukocyte enzyme assay and/or molecular sequencing, were de-identified and kindly provided by Greenwood Genetic Center (GGC) under their IRB protocol. These samples were used to establish the ARS-B enzyme activity range for affected patients.

Clinical assays were performed according to standard operation procedures developed at the Duke Biochemical Genetics Laboratory. Briefly, one 3.2 mm punch from a DBS card (3 μl of blood) was added to 200 μl of extraction buffer in a microfuge tube and incubated at room temperature (RT; 20–25 °C) for 2 h on a rocker. 40 μl aliquots of the DBS extract were transferred to four duplicate wells of the 96-well microtiter plate. 40 μl 4-MUS substrate solution was added to two duplicate reaction wells, while the remaining two wells served as duplicate sample blanks (no substrate). The plate was sealed with adhesive aluminum foil and incubated at 37 °C for 20 h along with the remaining 4-MUS solution in a tube. The reaction was subsequently terminated by adding 220 μl of stop buffer (85 mmol/L glycine-NaOH) to all wells. The remaining 4-MUS substrate was added to the duplicate blank wells to measure background fluorescence from the undigested substrate. The microplates were read using a benchtop fluorometer (Tecan, Austria) and the mean fluorescence of the duplicate blank wells was subtracted from that of the reaction wells to calculate the relative fluorescence units (RFU) for each sample. The RFU was then plotted against a freshly prepared 4MU standard curve and converted to enzyme activity units, expressed in pmol/punch*h, based on the standard curve.

2.3. Assay validation

A set of eight normal control DBS were assayed five times within one plate to determine the intra-day assay variability. Ten normal control spots were assayed individually on six different days to establish the inter-day assay variability. All spots were stored at − 20 °C between assays. Two different analysts tested the same set of ten DBS to determine operator variability as part of the validation process. In addition, DBS extracts were serially diluted (1:5, 1:10, 1:25, 1:50, 1:100 and 1:200) to establish the least detectable activity measurement (limit of detection). Stability of ARS-B enzyme activity in DBS under different storage conditions was also analyzed. A set of ten individual DBS were stored at − 20 °C, 4 °C and 22 °C (RT) for 7 days, 30 °C for 6 h and 37 °C for 2 h before measuring enzyme activity. Storage at 30 °C and 37 °C was intended to mimic short, high temperature transportation times as in a delivery truck or samples being held transiently during shipping and receiving in warm climate regions. Specificity of the ARS-B enzyme activity assay was determined by testing the DBS samples from patients with other known LSDs (MPS I, MPS II, MPS IVA, Gaucher, Fabry and Pompe).

3. Results and discussion

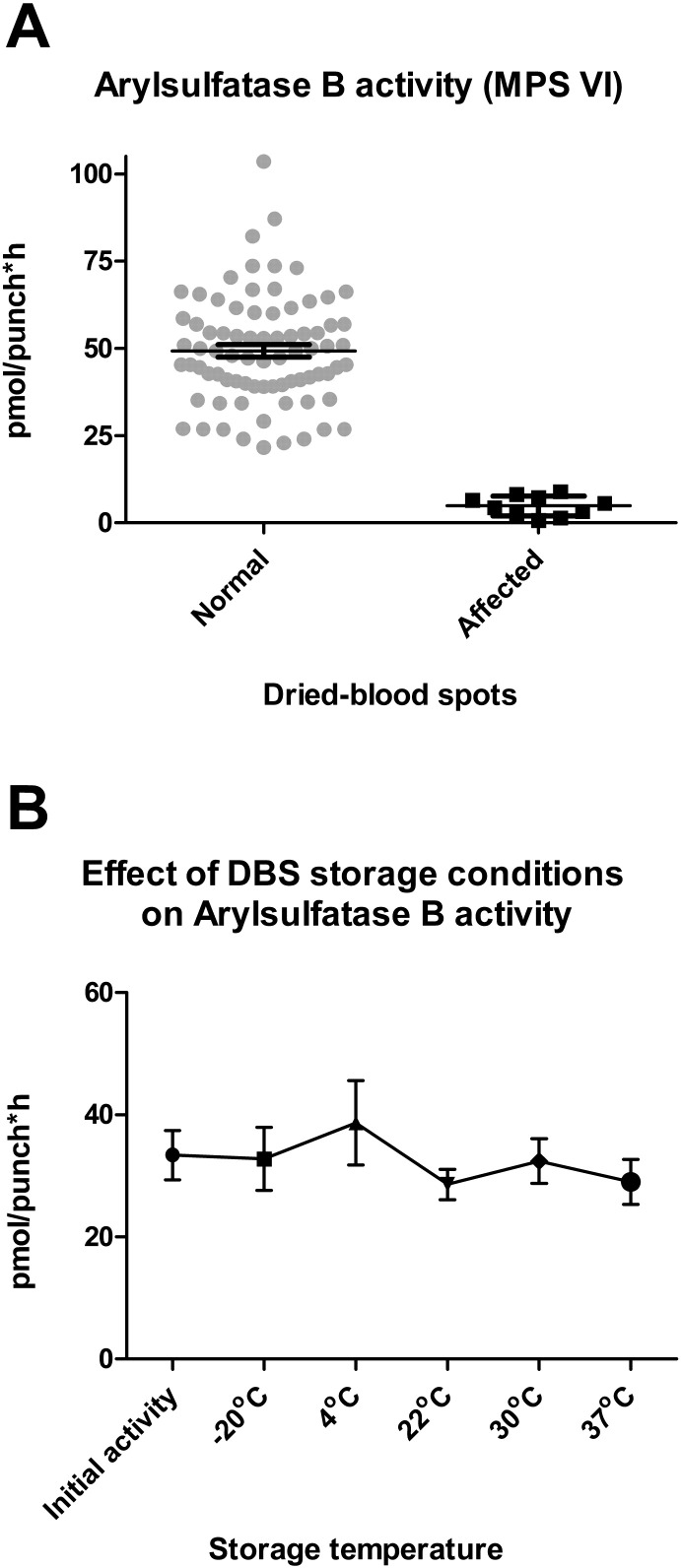

Fig. 1A shows the relative ARS-B enzyme activity in the DBS tested from normal and known MPS VI patients. The Duke-BGL control DBS (gray circles) showed an enzyme activity range of 21.6–103.6 pmol/punch*h. The calculated mean ± standard deviation values were 49.3 ± 15.6 pmol/punch*h. The MPS VI-affected DBS (black squares) showed enzyme activity ranging between 0.7–8.9 pmol/punch*h with a mean value of 4.8 ± 2.8 (mean ± std. dev.). The ARS-B deficient DBS activity levels were clearly separated and distinguishable from those of normal control spots (p < 0.0001, Tukey's t-test).

Fig. 1.

A) ARS-B enzyme activity comparison between normal control (circles) and MPS VI affected (squares) dried blood spots. Error bars show mean and SEM. B) Stability of ARS-B activity in dried-blood spots stored at different temperatures and durations (initial activity; − 20 °C, 4 °C & 22 °C for 7 days; 30 °C for 6 h; 37 °C for 2 h).

Stability experiments carried out to measure ARS-B activity over various lengths of times and temperatures using ten DBS samples ranged from 28.6–38.7 pmol/punch*hour and showed that the enzyme activity was relatively stable, with no significant difference under the various conditions tested (Fig. 1B). Storage at the higher temperatures (30 °C & 37 °C) for shorter durations was tested because DBS may often be exposed to such conditions during transportation, temporary storage and handling in certain situations.

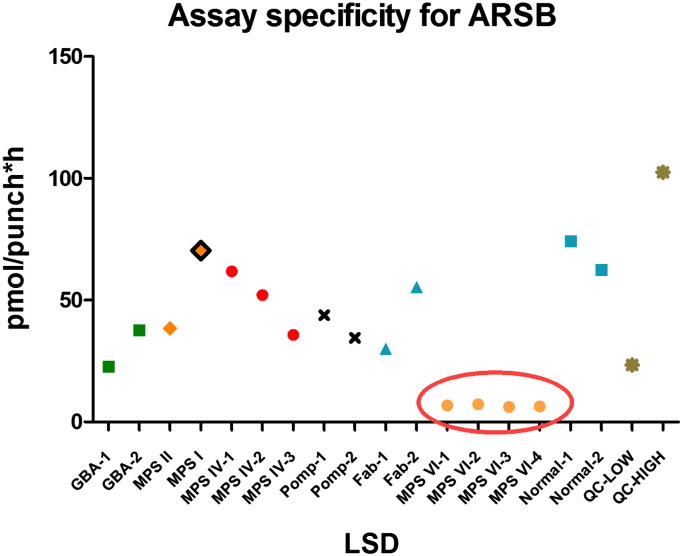

The inter-day (n = 10) and intra-day (n = 8) variations (%CV) of the fluorometric assay remained within acceptable limits (< 16.05% and < 13.88%, respectively), as was the operator variation (n = 10; CV < 14.75%), demonstrating the robustness and reproducibility of this new microplate assay. The assay was sensitive enough to detect enzymatic activity in normal control DBS extracts at 1:25 dilution (data not shown). This assay was also shown to be specific to MPS VI patients as DBS from patients with other LSDs (MPS I, MPS II, MPS IVA, Gaucher, Fabry and Pompe) showed ARS-B activities in the normal ranges (22.8–70.4 pmol/punch*h) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the ARS-B assay in DBS from affected MPS VI patients with those affected by other MPS showing the specificity of the assay for the target enzyme.

The use of minimally invasive DBS samples for diagnosis of MPS VI is advantageous due to the ease of sample procurement and shipping compared to the existing diagnostic methods that require cultured skin fibroblast cells or venous blood draw for leukocyte isolation [1]. DBSs can be conveniently shipped through the mail to distant clinical laboratories for testing since the enzyme activity is demonstrably stable under a range of storage conditions, including those that may be encountered in hot climates. These advantages make this DBS-based fluorescent microplate assay desirable as a screening tool to identify patients with MPS VI. It is, however, recommended to confirm the diagnosis using another method (enzyme activity in leukocytes or fibroblasts) or by molecular analysis, if possible.

4. Conclusions

We have developed and validated a new dried blood spot-based microplate assay using a fluorescent substrate for measuring arylsulfatase B activity to diagnose patients with MPS VI. This assay is robust, reproducible and more convenient than the existing, more labor-intensive assay techniques that require fibroblast cultures or blood leukocytes.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a sponsored research agreement with BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc. (No. 3938453). We wish to thank Dr. Tim Wood, Greenwood Genetic Center, for providing invaluable MPS VI patient DBS specimens.

References

- 1.Valayannopoulos V., Nicely H., Harmatz P., Turbeville S. Mucopolysaccharidosis VI. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2010;5:5. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giugliani R., Lampe C., Guffon N., Ketteridge D., Leao-Teles E., Wraith J.E., Jones S.A., Piscia-Nichols C., Lin P., Quartel A., Harmatz P. Natural history and galsulfase treatment in mucopolysaccharidosis VI (MPS VI, Maroteaux–Lamy syndrome)—10-year follow-up of patients who previously participated in an MPS VI survey study. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2014;9999:1–12. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noh H., Lee J.I. Current and potential therapeutic strategies for mucopolysaccharidoses. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2014;39:215–224. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muenzer J. Early initiation of enzyme replacement therapy for the mucopolysaccharidoses. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2014;111:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duffey T.A., Sadilek M., Scott C.R., Turecek F., Gelb M.H. Tandem mass spectrometry for the direct assay of lysosomal enzymes in dried blood spots: application to screening newborns for mucopolysaccharidosis VI (Maroteaux–Lamy syndrome) Anal. Chem. 2010;82:9587–9591. doi: 10.1021/ac102090v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chennamaneni N.K., Kumar A.B., Barcenas M., Spacil Z., Scott C.R., Turecek F., Gelb M.H. Improved reagents for newborn screening of mucopolysaccharidosis types I, II, and VI by tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2014;86:4508–4514. doi: 10.1021/ac5004135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Civallero G., Michelin K., de Mari J., Viapiana M., Burin M., Coelho J.C., Giugliani R. Twelve different enzyme assays on dried-blood filter paper samples for detection of patients with selected inherited lysosomal storage diseases. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2006;372:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tolun A.A., Graham C., Shi Q., Sista R.S., Wang T., Eckhardt A.E., Pamula V.K., Millington D.S., Bali D.S. A novel fluorometric enzyme analysis method for Hunter syndrome using dried blood spots. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012;105:519–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sista R.S., Wang T., Wu N., Graham C., Eckhardt A., Bali D., Millington D.S., Pamula V.K. Rapid assays for Gaucher and Hurler diseases in dried blood spots using digital microfluidics. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2013;109:218–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]