Abstract

Background

The American Heart Association introduced the Life's Simple 7 (LS7) metrics to assess and promote cardiovascular health. We examined the association between the LS7 metrics and noncardiovascular disease.

Methods and Results

We studied 6506 men and women aged between 45 and 84 years, enrolled in the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Median follow‐up time was 10.2 years. Each component of the LS7 metrics (smoking, body mass index, physical activity, diet, total cholesterol, blood pressure, and blood glucose) was assigned points, 0 indicates “poor” category; 1, “intermediate,” and 2, “ideal.” The LS7 score, ranged from 0 to 14, was created from the points and categorized as optimal (11–14), average (9–10), and inadequate (0–8). Hazard ratios and event rates per 1000 person‐years were calculated for outcomes based on self‐reported hospitalizations with the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, diagnoses of cancer, chronic kidney disease, pneumonia, deep venous thromboembolism/pulmonary embolism, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dementia, and hip fracture. Analyses were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and education. Overall, noncardiovascular disease event rates were lower with increasing LS7 scores. With the inadequate LS7 score as reference, an optimal score was associated with a decreased risk for noncardiovascular disease events. The hazard ratio for cancer was, 0.80 (0.64–0.98); chronic kidney disease, 0.38 (0.27–0.54); pneumonia, 0.57 (0.40–0.80); deep venous thromboembolism/pulmonary embolism, 0.52 (0.33–0.82), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 0.51 (0.31–0.83).

Conclusions

The American Heart Association's LS7 score identified individuals who were vulnerable to multiple chronic nonvascular conditions. These results suggest that improving cardiovascular health will also reduce the burden of cancer and other chronic diseases.

Keywords: epidemiology, Life's Simple 7, prevention, risk factor

Subject Categories: Race and Ethnicity, Lifestyle, Exercise, Diet and Nutrition, Obesity

Introduction

In the United States (US), the burden of noncardiovascular diseases (non‐CVDs) such as cancers and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is substantial.1 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, non‐CVDs were responsible for over 1 500 000 deaths combined in 2011.2 Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the US behind cardiovascular diseases (CVDs),2 and the age‐standardized prevalence of COPD in some US states is as high as 9%.3

The American Heart Association's (AHA's) 2020 impact goal is to improve the cardiovascular health (CVH) of all Americans by 20% by 2020, while reducing deaths from CVD and stroke by 20%.4 Implicit in this goal is improvement for all Americans including underserved racial groups and across the age spectrum. To achieve this goal, a new concept, ideal CVH, was introduced as a means to assess, monitor, and promote CVH and wellness.4 Ideal CVH is defined as the presence of 4 ideal health behaviors (nonsmoking, body mass index [BMI] <25 kg/m2, physical activity at goal levels, and diet consistent with recommended guidelines) and 3 ideal health factors (untreated total cholesterol <200 mg/dL, blood pressure (BP) <120/80 mm Hg, and fasting blood glucose <100 mg/dL). These 7 health behaviors and factors have been termed Life's Simple 7 (LS7) metrics.4 The inverse relationship between ideal CVH and CVD incidence is well documented.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 However, research exploring the association between ideal CVH and non‐CVDs has just begun.15, 16, 17, 18, 19

Our aim in this study was to examine the association between the AHA's LS7 metrics and non‐CVDs among participants of the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), an ethnically diverse study population. We hypothesized that participants with optimal LS7 scores would be less likely to develop non‐CVDs.

Methods

Study Population

MESA is a multicenter, prospective cohort study that started in 2000. Individuals between the ages of 45 and 84 years, free of clinical CVD at baseline, were recruited to investigate the prevalence, correlates, and progression of subclinical CVD. Details of the study design have been previously described.20 The sample size was 6814 participants of whom 38% of participants were white, 28% Black, 23% Hispanic, and 11% Chinese‐American. Recruitment from 6 field centers (Baltimore, MD; Chicago, IL; Forsyth County, NC; Los Angeles, CA; New York, NY; and St Paul, MN) occurred between July 2000 and September 2002. Informed consent was obtained from study participants and the study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the 6 field centers. The present study included 6506 MESA participants. Our exclusion criteria were incomplete baseline data on education, income, or the LS7 metrics (n=308). Data collection was between 2000 and 2015 while analysis was conducted in 2015.

Measurement of LS7 Metrics

Between 2000 and 2002, baseline levels of LS7 metrics (smoking, BMI, physical activity, diet, BP, total cholesterol, and blood glucose) were measured and categorized into ideal, intermediate, and poor according to the AHA criteria4 (Table S1) with modifications in MESA as previously reported.21 Smoking status was assessed using questionnaires developed by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III, the National Health Interview Survey, and Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC). Participants were classified as current smokers, former smokers if they quit within the past 12 months, or never smokers if they quit more than 12 months ago. BMI was calculated from height and weight measurements. Physical activity was measured using a detailed questionnaire adapted from the Cross‐Cultural Activity Participation Study.22 The questionnaire identifies the time and frequency spent in activities during a typical week in the previous month using 28 questions including household chores, lawn/yard/garden/farm, care of children/adults, transportation, walking (not at work), dancing and sport activities, conditioning activities, leisure activities, and occupational and volunteer activities. Minutes of walking, conditioning, and leisure activities were also included as exercise, and the minutes of moderate and vigorous exercise were calculated from the questionnaire. Diet assessment was performed using a validated 120‐item food frequency questionnaire modified from the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study instrument.23, 24 Diet was defined according to AHA criteria using 5 components of healthy diet (high intake of fruits and vegetables, fish, whole grains, low intake of sodium and sugar‐sweetened beverages).4 For BP, 3 measurements were taken after participants had rested for 5 minutes. The average of the last 2 measurements was recorded and used for analysis. Total cholesterol and blood glucose levels were obtained from fasting blood samples.

We used a previously defined scoring system21 where points were assigned to each category of the LS7 metrics and summed: ideal=2 points, intermediate=1 point, and poor=0 point, for a total score ranging from 0 to 14 points.25 Study participants who scored 0 to 8 points were classified as inadequate, those who scored 9 or 10 points were classified as average, and participants who scored 11 to 14 points were classified as optimal.21 Table S1 presents the proportion of MESA participants who fall into each category of the metrics.

Non‐CVD Outcomes

Participants of MESA were followed up every 9 to 12 months for a median of 10.2 years (mean=9.5 years, interquartile range 9.7–10.7 years) and self‐reported any hospitalizations that had occurred since the last follow‐up. Upon report of a hospitalization, medical records were requested. The protocols and criteria for verification and diagnosis of non‐CVD events have been previously reported.20 Non‐CVD diagnoses were extracted from inpatient records using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD‐9). For this study, we included ICD‐9 codes related to the following categories: any malignant neoplasm, chronic kidney disease (CKD) and indicators of end‐stage kidney disease, pneumonia, deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE), COPD, dementia, and hip fracture. A complete list of the codes used is presented in Table S2. Coronary heart disease (CHD) and CVD events were adjudicated by the MESA mortality and morbidity review committee.

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics of study participants such as sex, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (education and income) were reported by the LS7 score. Categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentages while continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). Comparison between the characteristics of participants and the LS7 score were tested using chi‐square tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. The event rate per 1000 person‐years for each non‐CVD diagnosis was calculated. In a multivariable‐adjusted model, we calculated the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for each non‐CVD diagnosis analyzed separately by the categories of the LS7 score (inadequate LS7 score served as reference) and the HR (95% CI) of the aggregate measure of the first occurrence of any of the non‐CVD diagnoses. Covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. We constructed Kaplan–Meier curves for non‐CVD‐free survival. Two separate sensitivity analyses were performed where participants with any nonfatal CHD event or nonfatal CVD event at or before the time of the non‐CVD diagnosis were excluded from the study sample. These accounted for the potential identification bias of a comorbid illness during admission for CHD or CVD. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) with the exception of the Kaplan–Meier curves, which were constructed using Stata 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

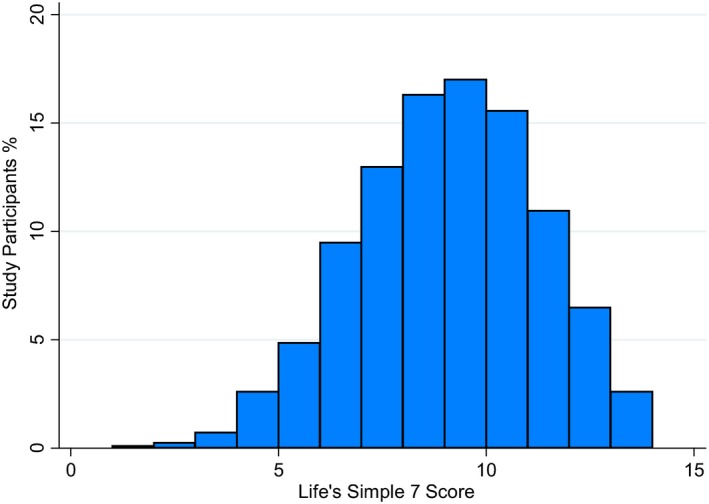

Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Among the 6506 study participants, 20.1% had optimal LS7 scores, 32.6% had average scores, and 47.3% had inadequate scores. The distribution of the LS7 score is presented in Figure 1. Participants with optimal scores were more likely to be Caucasian or have more than a college education while those with inadequate scores were more likely to be on medication for hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, or diabetes mellitus (Table 1). Approximately 0.1% of participants met the ideal criteria for all 7 components of the LS7 metrics.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants by Life's Simple 7 Score

| Characteristics | All Participants (N=6506) | Inadequate (0–8) (n=3080) | Average (9–10) (n=2120) | Optimal (11–14) (n=1306) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 62.0 (10.2) | 62.7 (9.8) | 62.0 (10.5) | 60.3 (10.5) | <0.001a |

| Sex | |||||

| Women | 3432 (52.8%) | 1615 (52.4%) | 1118 (52.7%) | 699 (53.5%) | 0.80 |

| Men | 3074 (47.2%) | 1465 (47.6%) | 1002 (47.3%) | 607 (46.5%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001a | ||||

| Caucasian | 2539 (39.0%) | 979 (31.8%) | 908 (42.8%) | 652 (49.9%) | |

| Chinese | 795 (12.2%) | 216 (7.00%) | 318 (15.0%) | 261 (20.0%) | |

| Black | 1716 (26.4%) | 1043 (33.9%) | 474 (22.4%) | 199 (15.2%) | |

| Hispanic | 1456 (22.4%) | 842 (27.3%) | 420 (19.8%) | 194 (14.9%) | |

| Education | <0.001a | ||||

| <High school education | 1157 (17.8%) | 691 (22.4%) | 341 (16.1%) | 125 (9.6%) | |

| High school education | 1166 (17.9%) | 660 (21.4%) | 350 (16.5%) | 156 (11.9%) | |

| Some college education | 1852 (28.5%) | 993 (30.3%) | 595 (28.1%) | 324 (24.8%) | |

| College education | 1142 (17.6%) | 413 (13.4%) | 411 (19.4%) | 318 (24.4%) | |

| >College education | 1189 (18.3%) | 383 (12.4%) | 423 (20.0%) | 383 (29.3%) | |

| Income | <0.001a | ||||

| <$40 000 | 3292 (50.6%) | 1808 (58.7%) | 995 (46.9%) | 489 (37.4%) | |

| ≥$40 000 | 3214 (49.4%) | 1272 (41.3%) | 1125 (53.1%) | 817 (62.6%) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28 (5) | 31 (5) | 27 (5) | 24 (3) | |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 126.2 (21) | 134 (21) | 123.9 (20) | 111.3 (15) | <0.001a |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 72 (10) | 74 (10) | 71 (10) | 66.9 (8) | <0.001a |

| Antihypertensive therapy | 2113 (32%) | 1470 (48%) | 549 (26%) | 94 (7%) | <0.001a |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 194 (36) | 200 (39) | 193 (33) | 183 (28) | <0.001a |

| Antihypercholesterolemia therapy | 1050 (16%) | 704 (23%) | 273 (13%) | 73 (6%) | <0.001a |

| Diabetes mellitus | 756 (12%) | 598 (19%) | 134 (6%) | 24 (2%) | <0.001a |

| Antidiabetic therapy | 622 (10%) | 549 (18%) | 60 (3%) | 13 (1%) | <0.001a |

| Total number of medications | 3.2 (2.9) | 3.8 (3.0) | 2.9 (2.7) | 2.5 (2.6) | <0.001a |

| No health insurance | 581 (9%) | 288 (9%) | 175 (8%) | 118 (9%) | 0.39 |

BMI indicates body mass index; BP, blood pressure; SD, standard deviation. Mean and SD were reported for BMI, BP, total cholesterol and total number of medications.

Statistical significance (P<0.05).

Figure 1.

Distribution of the Life's Simple 7 (LS7) score. The LS7 score ranged from 0 to 14 and was classified into inadequate (0–8), average (9–10), and optimal (11–14) based on points assigned to each category of the LS7 metrics.

Cancer

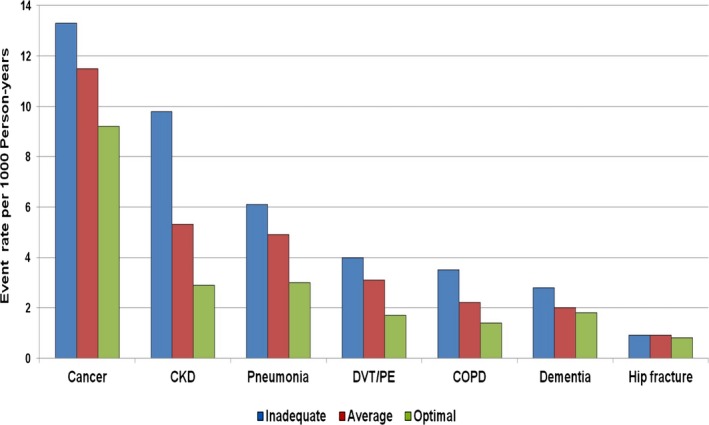

Cancer diagnosis codes (Table S2) were observed in 764 (11.7%) participants. The event rate of cancer per 1000 person‐years by LS7 score was 9.2, 11.5, and 13.3 for optimal, average, and inadequate scores, respectively (Figure 2). Those with inadequate LS7 scores accounted for 51.4% of cancer cases. Unadjusted and adjusted HRs are presented in Table 2. In multivariable‐adjusted models, with the inadequate scores serving as reference, participants with optimal scores had a 20% lower risk for developing cancer, and while not statistically significant, those with average scores had a 10% lower risk.

Figure 2.

Event rate per 1000 person‐years of study participants with noncardiovascular disease by Life's Simple 7 (LS7) score. The LS7 score ranged from 0 to 14 and was classified into inadequate (0–8), average (9–10), and optimal (11–14) based on points assigned to each category of the LS7 metrics. CKD indicates chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DVT/PE, deep venous thromboembolism/pulmonary embolism.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and Multivariable Adjusted HRs for Non‐Cardiovascular Diseases

| Non‐Cardiovascular Diseases | Unadjusted HR, 95% CI | Multivariable Adjusted HR, 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average (9–10) (n=2120) | Optimal (11–14) (n=1306) | Average (9–10) (n=2120) | Optimal (11–14) (n=1306) | |

| Cancer | 0.87 (0.74–1.01) | 0.69 (0.56–0.84) | 0.90 (0.77–1.06) | 0.80 (0.64–0.98) |

| CKD | 0.53 (0.43–0.66) | 0.29 (0.21–0.40) | 0.60 (0.48–0.74) | 0.38 (0.27–0.54) |

| Pneumonia | 0.79 (0.63–1.01) | 0.49 (0.35–0.69) | 0.82 (0.64–1.04) | 0.57 (0.40–0.80) |

| DVT/PE | 0.76 (0.56–1.02) | 0.42 (0.27–0.66) | 0.82 (0.60–1.11) | 0.52 (0.33–0.82) |

| COPD | 0.62 (0.44–0.87) | 0.41 (0.25–0.66) | 0.65 (0.46–0.92) | 0.51 (0.31–0.83) |

| Dementia | 0.69 (0.48–0.99) | 0.62 (0.40–0.96) | 0.67 (0.46–0.98) | 0.80 (0.50–1.27) |

| Hip fracture | 1.00 (0.57–1.76) | 0.83 (0.42–1.67) | 0.82 (0.46–1.45) | 0.71 (0.34–1.48) |

Multivariable model was adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and education. Inadequate score (0–8) served as reference. CKD indicates chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DVT/PE, deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism; HR, hazard ratio.

Chronic Kidney Disease

CKD was documented in 454 (7.0%) participants. The event rate of CKD was 2.9 cases per 1000 person‐years for optimal LS7 scores, 5.3 cases per 1000 person‐years for average scores, and 9.8 cases per 1000 person‐years for inadequate scores (Figure 2). The risk for developing CKD was 40% and 62% lower for those with average and optimal LS7 scores, respectively (Table 2). After excluding participants with estimated glomerular filtration rate ≤60 mL/min at baseline, HR was 0.49 (0.32–0.76) for participants with average scores and 0.29 (0.14–0.59) for those with optimal scores.

Pneumonia

Pneumonia was identified in 334 (5.1%) participants. The event rate was 6.1 cases per 1000 person‐years for participants with inadequate LS7 scores. Those with average scores had an event rate of 4.9 cases per 1000 person‐years (Figure 2) and the HR for developing pneumonia was 0.82 (0.64–1.04) (Table 2). Participants with optimal scores had a much lower event rate, 3.0 cases per 1000 person‐years, and a 43% lower risk for developing pneumonia.

DVT or PE

There were 215 (3.3%) cases of DVT or PE, with over half of the diagnoses made in participants with inadequate LS7 scores and 11% in participants with optimal scores. Event rates were 4.0, 3.1, and 1.7 per 1000 person‐years for participants with inadequate, average, and optimal scores, respectively (Figure 2). HRs for developing DVT or PE for participants with average and optimal scores were 0.82 (0.60–1.11) and 0.52 (0.33–0.82), respectively (Table 2).

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

COPD was identified in 174 (2.7%) participants. The majority of the diagnoses (61%) were in participants with inadequate scores. The event rate was ≈3 times higher in participants with inadequate scores compared with those with optimal scores, 3.5 cases versus 1.4 cases per 1000 person‐years (Figure 2). Participants with average and optimal scores had a 35% and 49% lower risk for developing COPD (Table 2). Similarly, the associations remained essentially unchanged after the exclusion of participants with a diagnosis of COPD at baseline. The HR was 0.60 (0.41–0.89) for participants with an average score and 0.48 (0.28–0.83) for those with optimal scores.

Dementia

Dementia was documented in 156 (2.4%) study participants. The event rates per 1000 person‐years were 1.8, 2.0, and 2.8 for the optimal, average, and inadequate LS7 scores, respectively (Figure 2). Participants with inadequate scores accounted for 55.8% of the diagnoses. For participants with optimal scores, the HR for developing dementia was 0.80 (0.50–1.27), while for those with average scores, the HR was 0.67 (0.46–0.98) (Table 2).

Hip Fractures

Hip fractures were observed in 61 (0.9%) study participants. Most of the cases (47.5%) were diagnosed in participants with inadequate LS7 scores while only 18% were in participants with optimal scores. The event rate for hip fractures was 0.9 cases per 1000 person‐years for both participants with inadequate and average scores. For those with optimal scores, the event rate was 0.8 per 1000 person‐years (Figure 2). Although not statistically significant, average and optimal scores were associated with a lower risk for developing hip fractures (HR 0.82 [0.46–1.45] and HR 0.71 [0.34–1.48], respectively (Table 2).

Sensitivity Analyses

In the stratified analyses presented in Table 3, the risk for developing non‐CVDs was lower irrespective of age, sex, and race/ethnicity for participants with optimal and average scores compared with those with inadequate scores. However, many of the associations were not statistically significant. In addition, there was little difference between the results before and after the exclusion of participants with an interim or concurrent nonfatal CHD event or nonfatal CVD event. Although some results were not statistically significant, the risk for developing non‐CVD events remained lower for those with average and optimal scores (Tables 4 and 5). As illustrated in Table 6, the ideal and intermediate categories of the health behaviors and factors of the LS7 metrics, particularly smoking, physical activity, BP, and blood glucose were associated with a lower risk of developing non‐CVDs, although some of the associations were not statistically significant. Event rates per 1000 person‐years by age, sex, and race/ethnicity are presented in Figures S1 through S12. Overall, optimal LS7 scores were associated with a lower risk and event rates of non‐CVDs.

Table 3.

Multivariable Adjusted HRs for Non‐Cardiovascular Diseases Stratified by Age, Sex, and Race/Ethnicity

| Characteristics | Cancer | CKD | Pneumonia | DVT/PE | COPD | Dementia | Hip Fracture | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted HR | Adjusted HR | Adjusted HR | Adjusted HR | Adjusted HR | Adjusted HR | Adjusted HR | ||||||||

| Average | Optimal | Average | Optimal | Average | Optimal | Average | Optimal | Average | Optimal | Average | Optimal | Average | Optimal | |

| Age, y | ||||||||||||||

| <65 | 0.83 (0.62–1.09) | 0.93 (0.67–1.28) | 0.47 (0.31–0.72) | 0.34 (0.19–0.63) | 0.70 (0.46–1.08) | 0.51 (0.29–0.92) | 0.79 (0.48–1.31) | 0.62 (0.31–1.21) | 0.76 (0.42–1.37) | 0.38 (0.15–0.98) | — | 0.39 (0.04–3.99) | 0.68 (0.19–2.40) | 0.49 (0.09–2.55) |

| ≥65 | 0.96 (0.78–1.17) | 0.71 (0.54–0.95) | 0.66 (0.51–0.85) | 0.39 (0.26–0.59) | 0.89 (0.66–1.20) | 0.58 (0.37–0.90) | 0.86 (0.57–1.27) | 0.47 (0.25–0.87) | 0.63 (0.41–0.98) | 0.58 (0.32–1.04) | 0.72 (0.49–1.05) | 0.82 (0.51–1.32) | 0.87 (0.45–1.66) | 0.81 (0.36–1.83) |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||

| Female | 0.93 (0.73–1.20) | 0.83 (0.60–1.15) | 0.53 (0.37–0.75) | 0.25 (0.14–0.46) | 0.76 (0.52–1.10) | 0.37 (0.20–0.70) | 0.62 (0.40–0.95) | 0.43 (0.23–0.82) | 0.49 (0.28–0.84) | 0.42 (0.19–0.92) | 0.52 (0.30–0.90) | 0.44 (0.19–1.00) | 0.74 (0.36–1.53) | 0.79 (0.33–1.90) |

| Male | 0.88 (0.71–1.09) | 0.74 (0.56–0.98) | 0.62 (0.47–0.83) | 0.45 (0.30–0.67) | 0.88 (0.64–1.21) | 0.71 (0.46–1.08) | 1.14 (0.74–1.76) | 0.63 (0.33–1.20) | 0.81 (0.51–1.27) | 0.57 (0.30–1.09) | 0.85 (0.51–1.41) | 1.13 (0.64–2.01) | 0.93 (0.36–2.41) | 0.55 (0.15–2.09) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||||

| White | 0.84 (0.66–1.07) | 0.89 (0.67–1.18) | 0.55 (0.39–0.78) | 0.37 (0.23–0.61) | 0.74 (0.52–1.05) | 0.57 (0.36–0.91) | 0.75 (0.48–1.18) | 0.63 (0.36–1.09) | 0.77 (0.47–1.26) | 0.64 (0.33–1.24) | 0.71 (0.42–1.22) | 0.81 (0.42–1.53) | 0.86 (0.44–1.68) | 0.70 (0.29–1.68) |

| Black | 0.91 (0.67–1.23) | 0.76 (0.47–1.22) | 0.53 (0.34–0.83) | 0.57 (0.29–1.09) | 1.06 (0.61–1.84) | 0.57 (0.20–1.60) | 0.86 (0.51–1.47) | 0.47 (0.17–1.31) | 0.39 (0.18–0.88) | 0.30 (0.07–1.27) | 0.70 (0.34–1.44) | 0.37 (0.09–1.60) | 1.50 (0.25–9.06) | — |

| Hispanic | 1.07 (0.73–1.58) | 0.39 (0.18–0.86) | 0.64 (0.41–0.99) | 0.30 (0.13–0.70) | 0.88 (0.53–1.46) | 0.57 (0.24–1.33) | 1.01 (0.48–2.11) | — | 0.73 (0.28–1.88) | 0.26 (0.03–1.99) | 0.47 (0.18–1.26) | 0.47 (0.11–2.02) | — | 0.55 (0.06–5.06) |

| Chinese American | 1.12 (0.59–2.14) | 0.82 (0.39–1.70) | 0.78 (0.40–1.53) | 0.21 (0.07–0.63) | 0.99 (0.43–2.27) | 0.67 (0.25–1.79) | 0.66 (0.16–2.67) | 0.22 (0.03–2.01) | 0.71 (0.26–1.89) | 0.61 (0.20–1.89) | 0.47 (0.10–2.18) | 1.52 (0.42–5.49) | — | — |

Multivariable model was adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and education. Inadequate score served as reference. — indicates insufficient data; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DVT/PE, deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism; HR, hazard ratio.

Table 4.

HRs for Non‐Cardiovascular Diseases After Exclusion of Participants With Interim or Concurrent Nonfatal Coronary Heart Disease Events

| Non‐Cardiovascular Diseases | Number of Participants Excluded | Average (9–10) | Optimal (11–14) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | 55 | 0.90 (0.76–1.07) | 0.82 (0.66–1.02) |

| CKD | 72 | 0.60 (0.47–0.76) | 0.37 (0.26–0.54) |

| Pneumonia | 54 | 0.87 (0.67–1.13) | 0.60 (0.41–0.87) |

| DVT/PE | 20 | 0.86 (0.63–1.19) | 0.59 (0.37–0.94) |

| COPD | 28 | 0.63 (0.43–0.93) | 0.52 (0.30–0.89) |

| Dementia | 12 | 0.62 (0.42–0.91) | 0.82 (0.51–1.32) |

| Hip fracture | 6 | 0.83 (0.45–1.53) | 0.80 (0.38–1.68) |

| Any non‐CVD event | 173 | 0.66 (0.59–0.74) | 0.55 (0.48–0.64) |

Hazard ratios (HRs) were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and education. Inadequate score (0–8) served as reference. CKD indicates chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DVT/PE, deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism.

Table 5.

HRs for Non‐Cardiovascular Diseases After Exclusion of Participants With Interim or Concurrent Nonfatal CVD

| Non‐Cardiovascular Diseases | Number of Participants Excluded | Inadequate (9–10) | Optimal (11–14) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | 78 | 0.90 (0.76–1.07) | 0.84 (0.68–1.05) |

| CKD | 91 | 0.60 (0.47–0.76) | 0.39 (0.27–0.56) |

| Pneumonia | 65 | 0.84 (0.64–1.10) | 0.61 (0.42–0.89) |

| DVT/PE | 29 | 0.87 (0.63–1.21) | 0.63 (0.40–1.00) |

| COPD | 32 | 0.66 (0.45–0.96) | 0.54 (0.31–0.92) |

| Dementia | 28 | 0.59 (0.39–0.90) | 0.88 (0.54–1.45) |

| Hip fracture | 10 | 0.80 (0.42–1.51) | 0.84 (0.39–1.79) |

| Any non‐CVD event | 243 | 0.67 (0.59–0.74) | 0.57 (0.49–0.66) |

Hazard ratios (HRs) were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and education. Inadequate score (0–8) served as reference. CKD indicates chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DVT/PE, deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism.

Table 6.

HRs for Noncardiovascular Diseases by Baseline Levels of Life's Simple 7 Metrics

| Cancer | CKD | Pneumonia | DVT/PE | COPD | Dementia | Hip Fracture | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | |||||||

| Poor | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Intermediate | 0.65 (0.32–1.33) | 0.49 (0.15–1.56) | 0.86 (0.37–2.00) | 0.60 (014–2.53) | 1.13 (0.51–2.49) | — | 2.00 (0.43–9.33) |

| Ideal | 0.63 (0.51–0.78) | 0.84 (0.62–1.56) | 0.50 (0.37–0.67) | 0.71 (0.48–1.06) | 0.22 (0.16–0.32) | 0.54 (0.32–0.92) | 0.35 (0.17–0.73) |

| Body mass index | |||||||

| Poor | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Intermediate | 0.85 (0.72–1.01) | 0.62 (0.50–0.77) | 0.69 (0.53–0.89) | 0.65 (0.48–0.88) | 1.00 (0.68–1.47) | 0.99 (0.66–1.49) | 1.18 (0.58–2.41) |

| Ideal | 0.88 (0.72–1.07) | 0.57 (0.44–0.74) | 0.69 (0.51–0.92) | 0.53 (0.36–0.78) | 1.38 (0.93–2.07) | 1.27 (0.82–1.97) | 1.64 (0.80–3.36) |

| Physical activity | |||||||

| Poor | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Intermediate | 0.77 (0.61–0.98) | 0.96 (0.73–1.26) | 0.79 (0.57–1.11) | 0.66 (0.43–1.02) | 0.56 (0.36–0.88) | 0.80 (0.48–1.32) | 0.94 (0.44–2.00) |

| Ideal | 0.82 (0.69–0.97) | 0.66 (0.53–0.82) | 0.71 (0.55–0.91) | 0.70 (0.52–0.95) | 0.45 (0.33–0.63) | 0.73 (0.50–1.07) | 0.65 (0.35–1.21) |

| Diet | |||||||

| Poor | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Intermediate | 0.88 (0.76–1.02) | 0.90 (0.75–1.09) | 1.07 (0.86–1.34) | 0.81 (0.61–1.07) | 0.80 (0.58–1.09) | 1.10 (0.56–1.65) | 0.96 (0.56–1.65) |

| Ideal | 0.89 (0.44–1.81) | 0.39 (0.10–1.58) | — | 0.98 (0.31–3.11) | 0.44 (0.06–3.21) | 1.03 (0.25–4.26) | 1.03 (0.14–7.73) |

| Total cholesterol | |||||||

| Poor | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Intermediate | 1.03 (0.81–1.30) | 1.04 (0.77–1.40) | 1.39 (0.94–2.04) | 0.90 (0.60–1.36) | 1.29 (0.77–2.16) | 1.49 (0.85–2.62) | 1.39 (0.57–3.38) |

| Ideal | 1.13 (0.90–1.42) | 1.05 (0.78–1.41) | 1.59 (1.09–2.33) | 0.99 (0.66–1.50) | 1.38 (0.83–2.31) | 1.32 (0.75–2.32) | 1.69 (0.69–4.11) |

| Blood pressure | |||||||

| Poor | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Intermediate | 0.90 (0.75–1.07) | 0.68 (0.55–0.85) | 0.72 (0.55–0.94) | 1.09 (0.79–1.51) | 1.06 (0.74–1.52) | 0.78 (0.53–1.14) | 0.97 (0.54–1.75) |

| Ideal | 0.92 (0.76–1.10) | 0.42 (0.32–0.56) | 0.68 (0.51–0.91) | 1.01 (0.71–1.44) | 0.90 (0.60–1.34) | 0.78 (0.50–1.22) | 0.69 (0.34–1.38) |

| Blood glucose | |||||||

| Poor | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Intermediate | 1.03 (0.79–1.35) | 0.53 (0.40–0.70) | 0.81 (0.56–1.18) | 0.72 (0.44–1.18) | 0.83 (0.49–1.40) | 0.81 (0.48–1.38) | 0.46 (0.16–1.33) |

| Ideal | 0.93 (0.74–1.18) | 0.36 (0.29–0.46) | 0.65 (0.47–0.89) | 0.72 (0.48–1.07) | 0.72 (0.47–1.12) | 0.70 (0.45–1.09) | 0.65 (0.30–1.41) |

Hazard ratios (HRs) were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, and income. — indicates extremely small HR; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DVT/PE, deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism.

Discussion

Summary of Findings

In this multiethnic prospective cohort study, participants who had average and optimal LS7 scores were less likely to develop non‐CVDs when compared with participants with inadequate scores. Overall, the risk for developing non‐CVDs were particularly lower for those with optimal scores. However, the HRs for dementia and hip fractures were not statistically significant. Moreover, similar associations were observed across age, sex, and race/ethnic subgroups.

Comparison With Previous Studies

The LS7 metrics were introduced as a means of assessing, monitoring, and promoting CVH at both the individual and population levels. Numerous studies have established that higher numbers of ideal LS7 metrics or higher LS7 scores are strongly associated with favorable outcomes.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Our results are comparable to the findings of prior studies that have shown an inverse relationship between higher LS7 scores and the incidence of non‐CVD.15, 16, 17, 18, 19 In the ARIC study, Rasmussen‐Torvik et al demonstrated that participants with 6 or 7 ideal metrics had a 51% lower risk of cancer compared with those with 0 to 2 ideal metrics.15

Studies including the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study demonstrated that participants with intermediate and high LS7 scores have a lower incidence of cognitive impairment when compared with participants with inadequate LS7 scores.17, 18, 19 Muntner et al in the REGARDS study reported a significantly lower risk of developing end‐stage renal disease with increasing numbers of ideal LS7 metrics. In the same cohort, Olson et al found a favorable prognosis for the risk of incident VTE among participants with ideal CVH status. In our study we found that optimal and average LS7 scores were associated with lower event rates for non‐CVD outcomes such as COPD, pneumonia, and hip fracture. However, some of our results were not statistically significant.

It has been established that some components of the LS7 metrics such as smoking are known risk factors for COPD, pneumonia, and hip fractures while physical inactivity and nutritional deficiencies contribute to the pathophysiology of hip fractures.26, 27, 28 It is also of interest that obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) may reduce the risk of hip fractures in women.29 Additionally, the prognosis of COPD is worsened by the presence of comorbid illnesses such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus.30 Although research showing the association between the LS7 metrics and the aforementioned non‐CVD outcomes is sparse, prior studies have demonstrated that having higher numbers of ideal LS7 metrics are associated with a lower risk of mortality from all causes.10, 31, 32, 33

Furthermore, our study highlights the association between each LS7 metric and non‐CVD events. For example, achieving the ideal category for smoking and physical activity was associated with a lower risk for developing most of the non‐CVDs measured. In contrast, participants in the ideal category for diet and total cholesterol were more likely to have some of the non‐CVDs such as dementia and hip fracture, although the associations were not statistically significant. Detailed analysis from pooled studies will be required to further clarify the impact of the individual LS7 metrics on non‐CVD outcomes.

Implications

Healthcare expenditures have been continuously increasing over the years. In 2013, ≈$3 trillion was spent on healthcare in the US, an increase of 3.6% from the previous year and an estimated $9000 per person.34 Most of these expenses go towards the management of preventable diseases.35 The LS7 metrics may provide an effective avenue for reducing healthcare expenditure. The strategy of the concept is primordial prevention where efforts are directed at preventing the development of risk factors in contrast to primary or secondary prevention where the focus is on the prevention of the first occurrence or recurrence of a disease.4, 36 In a study on the association of ideal CVH and long‐term healthcare cost, Willis et al found that having more ideal components of the LS7 metrics in middle age was associated with lower CVD and non‐CVD healthcare costs in later life.37

Strengths and Limitations

The major strengths of this study include the large population‐based sample, the diverse ethnicity of participants, the detailed and validated collection of data, and the sensitivity analyses performed. Our study also has limitations. The use of self‐administered questionnaires for data collection on smoking, diet, and physical may be subject to recall bias. Because MESA uses self‐reported hospitalization and ICD hospital codes for identifying new cases of non‐CVDs, interpretation of time‐to‐non‐CVD events should be time‐to‐diagnosis and not time‐to‐disease onset.38 The use of ICD hospital codes may have led to under‐ascertainment of non‐CVD events and sampling bias towards the inclusion of severe cases of non‐CVDs, while inadvertently excluding mild cases that were managed in an outpatient setting.38 Also, confirmation of non‐CVD diagnosis was administrative and so does not represent systematically adjudicated events.20 We made reference to event rates because non‐CVD events were not excluded at baseline. Nevertheless, the results of the sensitivity analyses showed small changes in HRs after the exclusion of participants with estimated glomerular filtration rates <60 mL/min and those with a diagnosis of COPD at baseline.

Conclusions

The present study shows that favorable CVH status is significantly associated with lower rates of non‐CVD events. Encouraging individuals to optimize their CVH will serve as a means to improve overall well‐being at both the individual and population levels and may also curtail healthcare expenditures.

Sources of Funding

MESA is supported by contracts N01‐HC‐95159, N01‐HC‐95160, N01‐HC‐95161, N01‐HC‐95162, N01‐HC‐95163, N01‐HC‐95164, N01‐HC‐95164, N01‐HC‐95165, N01‐HC‐95166, N01‐HC‐95167, N01‐HC‐95168, and N01‐HC‐95169 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by grants UL1‐RR‐024156 and UL1‐RR‐025005 from the National Center for Research Resources.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Table S1. Components of the LS7 Score

Table S2. ICD‐9 Codes of Non‐CVD Diagnosis of Interest

Figure S1. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of participants <65 years with non‐CVD by LS7 Score.

Figure S2. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of participants' ≥65 years with non‐CVD by LS7 Score.

Figure S3. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of women with non‐CVD by LS7 Score.

Figure S4. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of men with non‐CVD by LS7 Score.

Figure S5. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of White participants with non‐CVD by LS7 Score.

Figure S6. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of African‐American participants with non‐CVD by LS7 Score.

Figure S7. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of Hispanic participants with non‐CVD by LS7 Score.

Figure S8. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of Chinese‐American participants with non‐CVD by LS7 Score.

Figure S9. Kaplan–Meier curves for non‐CVD events and the aggregate outcome of any non‐CVD diagnosis.

Figure S10. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of study participants with any non‐CVD event by LS7 Score.

Figure S11. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of participants with income <$40 000 with non‐CVD by LS7 Score.

Figure S12. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of participants with income ≥$40 000 with non‐CVD by LS7 Score.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of MESA for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003954 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003954)

References

- 1. Murray CJ, Atkinson C, Bhalla K; U.S. Burden of Disease Collaborators . The state of US health, 1990–2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310:591–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hoyert DL, Xu J. Deaths: preliminary data for 2011. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;61:1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang X, Holt JB, Lu H, Wheaton AG, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, Croft JB. Multilevel regression and poststratification for small‐area estimation of population health outcomes: a case study of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevalence using the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179:1025–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lloyd‐Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van Horn L, Greenlund K, Daniels S, Nichol G, Tomaselli GF, Arnett DK, Fonarow GC, Ho PM, Lauer MS, Masoudi FA, Robertson RM, Roger V, Schwamm LH, Sorlie P, Yancy CW, Rosamond WD; American Heart Association Strategic Planning Task F, Statistics C . Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association's strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121:586–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stamler J, Stamler R, Neaton JD, Wentworth D, Daviglus ML, Garside D, Dyer AR, Liu K, Greenland P. Low risk‐factor profile and long‐term cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality and life expectancy: findings for 5 large cohorts of young adult and middle‐aged men and women. JAMA. 1999;282:2012–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stampfer MJ, Hu FB, Manson JE, Rimm EB, Willett WC. Primary prevention of coronary heart disease in women through diet and lifestyle. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chiuve SE, McCullough ML, Sacks FM, Rimm EB. Healthy lifestyle factors in the primary prevention of coronary heart disease among men benefits among users and nonusers of lipid‐lowering and antihypertensive medications. Circulation. 2006;114:160–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Folsom AR, Yatsuya H, Nettleton JA, Lutsey PL, Cushman M, Rosamond WD; Investigators AS . Community prevalence of ideal cardiovascular health, by the American Heart Association definition, and relationship with cardiovascular disease incidence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1690–1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dong C, Rundek T, Wright CB, Anwar Z, Elkind MS, Sacco RL. Ideal cardiovascular health predicts lower risks of myocardial infarction, stroke, and vascular death across whites, blacks, and hispanics: the Northern Manhattan Study. Circulation. 2012;125:2975–2984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, Hong Y. Ideal cardiovascular health and mortality from all causes and diseases of the circulatory system among adults in the United States. Circulation. 2012;125:987–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wu S, Huang Z, Yang X, Zhou Y, Wang A, Chen L, Zhao H, Ruan C, Wu Y, Xin A. Prevalence of ideal cardiovascular health and its relationship with the 4‐year cardiovascular events in a northern Chinese industrial city. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:487–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kulshreshtha A, Vaccarino V, Judd SE, Howard VJ, McClellan WM, Muntner P, Hong Y, Safford MM, Goyal A, Cushman M. Life's Simple 7 and risk of incident stroke: the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study. Stroke. 2013;44:1909–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miao C, Bao M, Xing A, Chen S, Wu Y, Cai J, Chen Y, Yang X. Cardiovascular health score and the risk of cardiovascular diseases. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Folsom AR, Shah AM, Lutsey PL, Roetker NS, Alonso A, Avery CL, Miedema MD, Konety S, Chang PP, Solomon SD. American Heart Association's Life's Simple 7: avoiding heart failure and preserving cardiac structure and function. Am J Med. 2015;128:970–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rasmussen‐Torvik LJ, Shay CM, Abramson JG, Friedrich CA, Nettleton JA, Prizment AE, Folsom AR. Ideal cardiovascular health is inversely associated with incident cancer: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Circulation. 2013;127:1270–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Muntner P, Judd SE, Gao L, Gutierrez OM, Rizk DV, McClellan W, Cushman M, Warnock DG. Cardiovascular risk factors in CKD associate with both ESRD and mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1159–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Crichton GE, Elias MF, Davey A, Alkerwi A. Cardiovascular health and cognitive function: the Maine‐Syracuse Longitudinal Study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thacker EL, Gillett SR, Wadley VG, Unverzagt FW, Judd SE, McClure LA, Howard VJ, Cushman M. The American Heart Association Life's Simple 7 and incident cognitive impairment: the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000635 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reis JP, Loria CM, Launer LJ, Sidney S, Liu K, Jacobs DR, Zhu N, Lloyd‐Jones DM, He K, Yaffe K. Cardiovascular health through young adulthood and cognitive functioning in midlife. Ann Neurol. 2013;73:170–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Roux AVD, Folsom AR, Greenland P, Jacobs DR Jr, Kronmal R, Liu K. Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Unger E, Diez‐Roux AV, Lloyd‐Jones DM, Mujahid MS, Nettleton JA, Bertoni A, Badon SE, Ning H, Allen NB. Association of neighborhood characteristics with cardiovascular health in the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:524–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ainsworth BE, Irwin ML, Addy CL, Whitt MC, Stolarczyk LM. Moderate physical activity patterns of minority women: the Cross‐Cultural Activity Participation Study. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 1999;8:805–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Block G, Woods M, Potosky A, Clifford C. Validation of a self‐administered diet history questionnaire using multiple diet records. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43:1327–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mayer‐Davis EJ, Vitolins MZ, Carmichael SL, Hemphill S, Tsaroucha G, Rushing J, Levin S. Validity and reproducibility of a food frequency interview in a multi‐cultural epidemiologic study. Ann Epidemiol. 1999;9:314–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lloyd‐Jones DM. Improving the cardiovascular health of the US population. JAMA. 2012;307:1314–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mannino DM, Buist AS. Global burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trends. Lancet. 2007;370:765–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pripp AH, Dahl OE. The population attributable risk of nutrition and lifestyle on hip fractures. Hip Int. 2015;25:277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Almirall J, Bolibar I, Balanzó X, Gonzalez C. Risk factors for community‐acquired pneumonia in adults: a population‐based case–control study. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Johansson H, Kanis JA, Odén A, McCloskey E, Chapurlat RD, Christiansen C, Cummings SR, Diez‐Perez A, Eisman JA, Fujiwara S. A meta‐analysis of the association of fracture risk and body mass index in women. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mannino DM, Thorn D, Swensen A, Holguin F. Prevalence and outcomes of diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:962–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim JY, Ko YJ, Rhee CW, Park BJ, Kim DH, Bae JM, Shin MH, Lee MS, Li ZM, Ahn YO. Cardiovascular health metrics and all‐cause and cardiovascular disease mortality among middle‐aged men in Korea: the Seoul male cohort study. J Prev Med Public Health. 2013;46:319–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu Y, Chi HJ, Cui LF, Yang XC, Wu YT, Huang Z, Zhao HY, Gao JS, Wu SL, Cai J. The ideal cardiovascular health metrics associated inversely with mortality from all causes and from cardiovascular diseases among adults in a Northern Chinese industrial city. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yang Q, Cogswell ME, Flanders WD, Hong Y, Zhang Z, Loustalot F, Gillespie C, Merritt R, Hu FB. Trends in cardiovascular health metrics and associations with all‐cause and CVD mortality among US adults. JAMA. 2012;307:1273–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services . 2015. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/. Accessed April 1, 2015.

- 35. Schroeder SA. Shattuck Lecture. We can do better–improving the health of the American people. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1221–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Strasser T. Reflections on cardiovascular diseases. Interdiscip Sci Rev. 1978;3:225–230. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Willis BL, DeFina LF, Bachmann JM, Franzini L, Shay CM, Gao A, Leonard D, Berry JD. Association of ideal cardiovascular health and long‐term healthcare costs. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49:678–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Handy CE, Desai CS, Dardari ZA, Al‐Mallah MH, Miedema MD, Ouyang P, Budoff MJ, Blumenthal RS, Nasir K, Blaha MJ. The association of coronary artery calcium with noncardiovascular disease: the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:568–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Components of the LS7 Score

Table S2. ICD‐9 Codes of Non‐CVD Diagnosis of Interest

Figure S1. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of participants <65 years with non‐CVD by LS7 Score.

Figure S2. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of participants' ≥65 years with non‐CVD by LS7 Score.

Figure S3. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of women with non‐CVD by LS7 Score.

Figure S4. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of men with non‐CVD by LS7 Score.

Figure S5. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of White participants with non‐CVD by LS7 Score.

Figure S6. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of African‐American participants with non‐CVD by LS7 Score.

Figure S7. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of Hispanic participants with non‐CVD by LS7 Score.

Figure S8. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of Chinese‐American participants with non‐CVD by LS7 Score.

Figure S9. Kaplan–Meier curves for non‐CVD events and the aggregate outcome of any non‐CVD diagnosis.

Figure S10. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of study participants with any non‐CVD event by LS7 Score.

Figure S11. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of participants with income <$40 000 with non‐CVD by LS7 Score.

Figure S12. Event rate per 1000 person‐years of participants with income ≥$40 000 with non‐CVD by LS7 Score.