Abstract

Orchid species are critically dependent on mycorrhizal fungi for completion of their life cycle, particularly during the early stages of their development when nutritional resources are scarce. As such, orchid mycorrhizal fungi play an important role in the population dynamics, abundance, and spatial distribution of orchid species. However, less is known about the ecology and distribution of orchid mycorrhizal fungi. In this study, we used 454 amplicon pyrosequencing to investigate ecological and geographic variation in mycorrhizal associations in fourteen species of the orchid genus Dactylorhiza. More specifically, we tested the hypothesis that variation in orchid mycorrhizal communities resulted primarily from differences in habitat conditions where the species were growing. The results showed that all investigated Dactylorhiza species associated with a large number of fungal OTUs, the majority belonging to the Tulasnellaceae, Ceratobasidiaceae and Sebacinales. Mycorrhizal specificity was low, but significant variation in mycorrhizal community composition was observed between species inhabiting different ecological habitats. Although several fungi had a broad geographic distribution, Species Indicator Analysis revealed some fungi that were characteristic for specific habitats. Overall, these results indicate that orchid mycorrhizal fungi may have a broad geographic distribution, but that their occurrence is bounded by specific habitat conditions.

Since the early discoveries that orchid seeds require a fungus to germinate1,2, it has become more and more clear that orchid mycorrhizal fungi are determining factors that not only drive the local abundance and dynamics of individual orchid populations, but also impact on coexistence and the regional distribution of orchid species3. Changes in the composition, richness or abundance of orchid mycorrhizal fungi can therefore be expected to have profound effects on orchid fitness and as a result on orchid distribution4,5 and community composition6. However, little is known about the specific factors that affect the distribution and occurrence of orchid mycorrhizal fungi in natural environments3. Recent studies on various types of mycorrhizal fungi have shown that apart from chance events and dispersal limitation7,8, variation in mycorrhizal communities can also result from differences in local environmental conditions7,9, often leading to correlated changes in mycorrhizal and plant communities across environmental gradients or distinct habitats10.

At present, there are relatively few empirical data on the factors driving variation in orchid mycorrhizal community composition across strong environmental gradients. Recent studies have shown that orchid mycorrhizal communities can vary substantially between species within sites6,11. In a similar way, mycorrhizal communities have been shown to vary between sites within species12,13. In this case, variation in mycorrhizal communities was significantly driven by variation in environmental conditions, which suggests that local growth conditions can impact on fungal communities. Further evidence for local environmental conditions affecting orchid mycorrhizal communities comes from comparisons of mycorrhizal communities across different habitats within a single orchid species. For example, it was recently shown that individuals from grassland populations of Neottia ovata associated with significantly different fungal communities than individuals from forest populations14. Similarly, pronounced differences in mycorrhizal communities were reported between dune slack and forest populations of Epipactis species. Overall, these results indicate that differences in habitat conditions can affect the occurrence of particular orchid mycorrhizal fungi and therefore impact on plant-fungus interactions in orchids15.

In this study, we investigated differences in mycorrhizal communities among 14 species of the orchid genus Dactylorhiza. The genus Dactylorhiza consists of a large group of species that are widely distributed across the boreal and temperate zones of Europe, Asia, North America and Northern parts of Africa. Species of the genus Dactylorhiza occupy a wide range of habitats with contrasting soil conditions, including acid peat bogs, wet alkaline grasslands, dry meadows and forests16,17,18. Previous research has shown that mycorrhizal specificity in the genus is low and that most Dactylorhiza species commonly associate with a wide range of fungi of the Tulasnellaceae19,20,21,22. However, members of the Ceratobasidiaceae may also be sporadically observed19,23. Compared to other European orchid genera, Dactylorhiza is unusual in that it contains a large number of species with varying ploidy levels, including diploids, triploids, autotetraploids and a vast number of allotetraploid species18,24,25. The latter comprise groups of species whose origin stemmed from independent hybridization events occurring in various parts of Europe and the Mediterranean Basin. Because previous research has shown that orchid mycorrhizal communities may be significantly affected by ploidy level26, differences in ploidy level should be taken into account when investigating variation in mycorrhizal communities in orchids. Moreover, given that allopolyploid species carry the genomes of two different diploid progenitors, it is not unreasonable to assume that differences in ploidy level not only affect mycorrhizal associations, but that genome composition impacts on the mycorrhizal communities associating with orchid species as well.

To determine the relative importance of ploidy level and habitat conditions in determining mycorrhizal communities, we sampled fourteen Dactylorhiza species that were characterized by different ploidy levels and occupied distinct habitats, including Mediterranean grasslands and forests (D. sambucina, D. romana, D. insularis and D. markusii), peat bogs (D. sphagnicola, D. maculata), wetlands (D. fuchsii, D. majalis, D. viridis, D. elata), coastal habitats (D. praetermissa, D. incarnata) and alpine-boreal habitats (D. alpestris and D. lapponica). More specifically, we asked whether:

orchid species from different habitats associated with different mycorrhizal communities;

there were specific fungal OTUs that were significantly associated with a particular habitat type;

differences in ploidy level or genome composition had a significant impact on mycorrhizal communities.

Results

Fungal identity

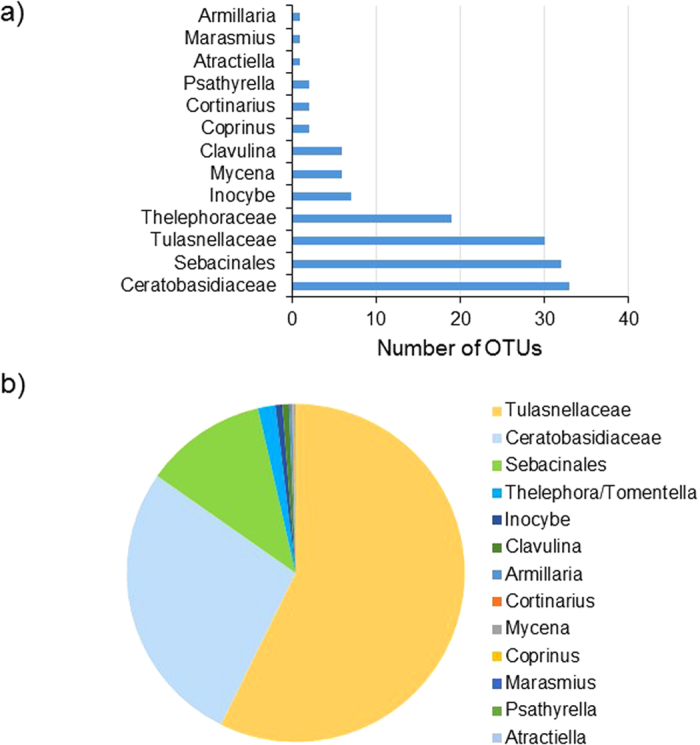

After exclusion of global singletons and doubletons, a total of 522 OTUs (94511 sequences) were retrieved, of which 115 (65754 sequences – 68.3% of all sequences) were considered as putative species of orchid mycorrhizal fungi (Table S1). Most orchid mycorrhizal fungi were related to members of the Tulasnellaceae (30 OTUs – 38402 sequences), Ceratobasidiaceae (33 OTUs – 18408 sequences) and Sebacinales (32 OTUs – 7835 sequences) (Fig. 1a,b). Besides a large number of ectomycorrhizal fungi related to Thelephora/Tomentella (19 OTUs) was also found, but the number of sequences (1106 sequences – 1.16% of the total number of sequences) was much lower (Fig. 2a,b). Additionally, some members of the fungal genera Armillaria (1 OTU), Atractiella (1 OTU), Clavulina (6 OTUs), Coprinus (2 OTUs), Cortinarius (2 OTUs) Inocybe (7 OTUs), Marasmius (1 OTU), Mycena (6 OTUs), and Psathyrella (2 OTUs) were sporadically observed (Fig. 1a), but in all cases the number of sequences was low (Fig. 1b). Because the mycorrhizal status of these fungi is doubtful, they were not considered in all subsequent analyses.

Figure 1. Diversity of putative orchid mycorrhizal fungi detected in the roots of fourteen Dactylorhiza species sampled in 35 populations across Europe.

(a) The number of OTUs belonging to different orchid families/genera. (b) Pie chart displaying the frequency distribution of sequences belonging to the different families/genera.

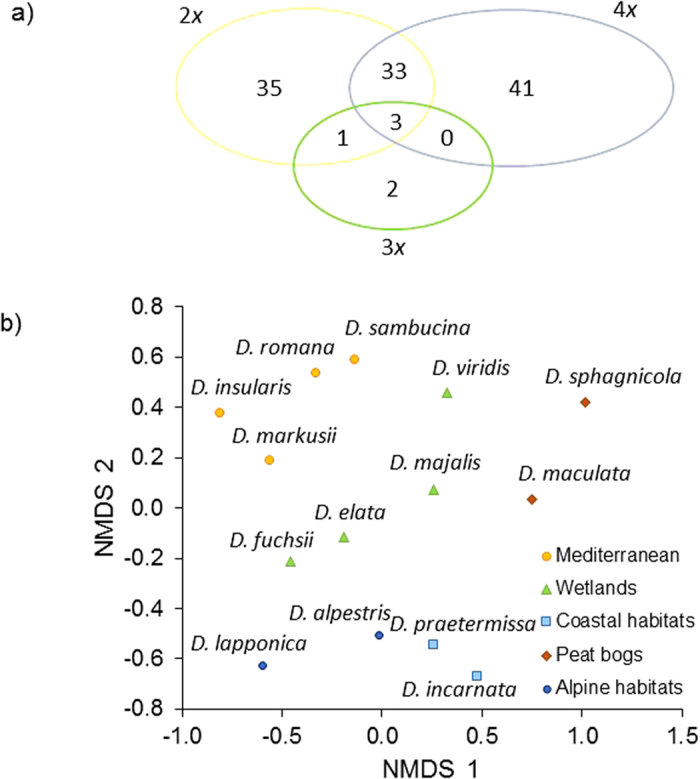

Figure 2. Partitioning of mycorrhizal communities detected in fourteen different Dactylorhiza species sampled in 35 populations across Europe.

(a) Venn diagram showing the number of OTUs that are shared between diploid (2x), triploid (3x) and tetraploid (4x) Dactylorhiza species. (b) Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plot of mycorrhizal fungi. Each point denotes a different Dactylorhiza species. Different colors denote the habitats from which the species were sampled.

Phylogenetic analyses of the Tulasnellaceae OTUs showed that they belonged to three well-supported clades (Fig. S1). Clades A and B have been previously shown to be mycorrhizal in orchids27, but the distantly related clade C appears to consist of a range of Tulasnella sequences that have only rarely been retrieved from orchids. All Ceratobasidiaceae OTUs belonged to a well-supported clade of closely related OTUs (Fig. S2), in which no strong subdivision was present. As to the Sebacinales, two major clades (Clade A and B) could be discerned corresponding to the two major groups with different ecological characteristics identified before28,29 (Fig. S3). In total, 9 OTUs (4350 sequences) were assigned to clade A and 23 OTUs (2592 sequences) were assigned to clade B (Fig. S3). However, only one OTU (OTU1) of clade A had a high sequence number and this OTU was exclusively retrieved in the alpine-boreal species D. lapponica and D. alpestris. Within the Thelephoraceae (Fig. S4), OTUs were found to be part of a well-supported clade, which included several Tomentella and Thelephora representatives. No further subdivision could be made.

Fungal diversity and association patterns

All Dactylorhiza species associated with a large number of orchid mycorrhizal fungi, most often members of the Tulasnellaceae and Ceratobasidiaceae, although members of the Thelephoraceae and Sebacinales were also frequently recovered. The total number of OTUs per orchid species varied between 6 (D. insularis) and 34 (D. fuchsii) (average: 17 OTUs per species). However, the majority of fungi was found in only one or two orchid species, indicating large turnover in mycorrhizal communities between the studied orchid species. Only one OTU (OTU4), which belonged to the Tulasnellaceae, occurred in more than half of the sampled orchid species. Two OTUs were found in half of the sampled species, one of which (OTU3) belonged to the Tulasnellaceae, while the other (OTU60) belonged to the Ceratobasidaceae. Four OTUs were detected in six Dactylorhiza species, three (OTU9, OTU10 and OTU18) of which belonged to the Tulasnellaceae and one (OTU11) to the Ceratobasidiaceae.

Within individual populations, a large number of mycorrhizal fungi was detected, confirming previous results that species of the genus Dactylorhiza show low specificity towards mycorrhizal fungi22. On average, nine different (range: 2–22) mycorrhizal OTUs were found in a population. Members of the Tulasnellaceae were detected in almost every population, but the number of OTUs was low in D. viridis, which mainly associated with members of the Ceratobasidiaceae. Members of the Ceratobasidiaceae were absent in populations of D. insularis. Sebacinales fungi were absent in populations of the Mediterranean species D. markusii and D. insularis, which primarily associated with Tulasnella and Thelephora OTUs. Finally, no fungi of the Thelephoraceae were observed in populations of D. maculata and D. viridis (Fig. S5).

Of the 115 detected OTUs that were considered orchid mycorrhizal, 77 OTUs were found in tetraploid species, 72 OTUs in diploid species and 6 OTUs in the triploid species (Fig. 2a). Three of these orchid mycorrhizal OTUs were shared between diploid, triploid and tetraploid species. Diploid and tetraploid species shared a total of 38 OTUs (Fig. 2a). The NMDS plot showed no clear differences between diploid and polyploid Dactylorhiza species, which was confirmed by the permanova analysis (pseudo-F = 1.158; P = 0.28) (Fig. S6). However, when plotting the habitat from which orchid species were sampled on the NMDS plot, clear differences between species from different habitats became apparent (Fig. 2b). These results were confirmed by the permanova analysis, which showed significant differences (pseudo-F = 2.58; P = 0.001) in mycorrhizal communities between species from different habitats. Species from Mediterranean habitats were clearly separated from the other groups at the upper part of the plot. Species sampled from peat bogs (D. maculata and D. sphagnicola) were located at the right-hand part of the plot, whereas species from wetlands were located somewhere intermediate between these two. Species from alpine-boreal habitats clustered together at the left hand site of the plot, whereas species from coastal habitats clustered together at the lower right hand side of the plot.

The modularity analysis showed that the network of interactions was significantly modular (Mobs = 0.4737, Mrandom = 0.4461 ± 0.0084, P < 0.001) and that six modules were identified (Fig. 3). The largest module consisted of four species and contained the four sampled species typically occurring in Mediterranean habitats (D. markusii, D. insularis, D. romana and D. sambucina) (Fig. 3). D. praetermissa and D. incarnata formed another module and represent species that were mainly sampled in coastal habitats. The module of D. maculata, D. sphagnicola and D. viridis showed less links to other modules. Finally, D. alpestris formed a module that consisted of a single species (Fig. 3). Broadly speaking, these modules can also be brought back to the habitats from which the orchids were sampled, but not to their ploidy level.

Figure 3. Matrix representation of the studied orchid mycorrhizal network encompassing fourteen Dactylorhiza species (rows) and putative orchid mycorrhizal operational taxonomic units (OTUs) (columns).

Different colors represent different modules. Red cells are species links gluing the six modules together into a coherent network, and non-red cells are links within modules.

Finally, Species Indicator Analysis identified three OTUs that were significantly associated with peat bogs (OTU5, OTU25 and OTU420), one OTU that significantly associated with alpine boreal habitats (OTU1) and two that associated with wetlands and Mediterranean habitats (OTU4 and OTU60). No OTUs were identified that significantly associated with a particular ploidy level.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the mycorrhizal communities associating with a large number of species of the orchid genus Dactylorhiza. Consistent with previous research, our results showed that species of the genus Dactylorhiza associated with a large suite of mycorrhizal fungi21,22. These results also confirm recent and more general observations that showed a high diversity of fungi associating with orchids in comparison with other mycorrhizal systems (arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, ectomycorrhizal fungi)30. The most abundant fungi were typical rhizoctonia fungi from the families Tulasnellaceae, Ceratobasidiaceae and Sebacinales. Members of the Tulasnellaceae and Ceratobasidiaceae have been repeatedly shown to associate with terrestrial temperate orchids from Europe27,31,32. Our results further confirm previous analyses that have shown that members of the Tulasnellaceae are the prime symbionts in Dactylorhiza20,21,22,23. The number of Tulasnella OTUs per species that was detected in an earlier study on Tulasnella diversity in five Dactylorhiza species22 was comparable with the numbers reported here for the same set of species (average: 6.4 ± 1.5 and 7.8 ± 3.4, respectively), despite fewer populations and individuals studied per species in the current study. At least seven Tulasnella OTUs (70%) showed strong genetic resemblance to previously detected OTUs, indicating that, we have picked up the majority of strains that were found associating with Dactylorhiza before. Besides, a considerable percentage of sequences belonged to OTUs of Sebacinales, most often members of clade B, although some representatives of clade A were also identified. Sebacinales of clade A are mainly ectomycorrhizal fungi that associate with trees and mycoheterotrophic orchids, whereas Sebacinales of clade B have been shown to be mycorrhizal fungi in Ericaceae, green orchids and liverworts28,29. However, recent research on the green orchid Neottia ovata has shown that Sebacinales of group A can be observed associating with green orchids as well13,33. Interestingly, Sebacinales of clade A were only retrieved from D. alpestris, D. lapponica and D. fuchsii, but not in the other species, suggesting that these fungi may be limited to particular habitats.

Besides these rhizoctonia fungi, we found a large number of ectomycorrhizal fungi of the Thelephoraceae. These fungi have previously been shown to associate with orchids that typically occur in forests. For example, the major fungi associating with the mycoheterotrophic Corallorhiza odonthorhiza were Tomentella fungi34. In the forest orchids Cephalanthera damasonium and C. longifolia several members of the Thelephoraceae, including Tomentella and Pseudotomentella, were found in germinating seeds35 (Bidartondo & Read 2008). Members of the Thelephoraceae were also detected in the forest orchid Neottia ovata13,33. However, recent investigations of a large number of terrestrial orchids in Mediterranean grasslands showed that associations with ectomycorrhizal fungi are not restricted to woodland orchids and that grassland orchids may also commonly associate with members of the Thelephoraceae36. Our results are clearly in line with these observations and suggest that these fungi may play a role in the life cycle of grassland orchids as well.

Although the precise factors driving local variation in fungal community structure and plant-fungal interactions remain largely unclear, there is mounting evidence that variation in local environmental conditions can generate pronounced differences in mycorrhizal communities9,10. Our results seem to confirm this as species from similar habitats clearly clustered together in the NMDS plot, whereas the occurrence of significant modularity indicates little overlap in mycorrhizal communities between species from different habitats. Recent research in the orchid genus Epipactis has shown similar habitat-dependent variation in mycorrhizal communities15. The co-occurring, but distantly related species E. neerlandica and E. palustris had much more fungi in common with each other than with E. helleborine that occurred in forests and from which E. neerlandica has been derived15. On the other hand, these findings are in contrast with a similar large-scale study on Orchis31,32, where no modularity was observed. However, in Orchis there was much less variation in habitats since most Orchis species typically occur in dry, nutrient-poor grasslands or forest edges with high pH.

The possibility that our results were partly the result of geographic proximities cannot be fully ruled out. However, the four species from the D. sambucina group that were studied here, were sampled across distances that were much larger than the ones separating wetland habitats, suggesting geographic proximity probably had a smaller impact on mycorrhizal communities. The closely related D. alpestris and D. lapponica clustered together in the NMDS plot and typically occur in boreal-alpine environments, but were sampled at sites that were more than 1500 km apart (alkaline seepages in the French Alps (D. alpestris) and boggy woods in Sweden (D. lapponica)). Individuals of D. sphagnicola and D. maculata were mainly sampled in strongly acidic peat bogs. Our results further showed that some of the retrieved fungi may be habitat generalists and have large geographic distribution ranges, since they were isolated from Dactylorhiza species from different habitat types and at fairly large distances from each other, whereas others may be habitat specialists. Indicator Species Analysis showed that at least three different fungi were significantly associated with peat bogs. Two Tulasnella fungi were also characteristic for Mediterranean habitats.

Apart from differences in habitat conditions, variation in mycorrhizal communities can also be shaped by differences in ploidy level26. Polyploids, for example, have been shown to be less dependent on mycorrhizal fungi, which play a substantial role in plant nutrient acquisition and coping with abiotic stress, than diploids, because they generally show a higher tolerance to nutrient stress, drought, cold, or salinity37. However, we found no significant differences in mycorrhizal community composition between diploid, triploid and tetraploid species and no fungal OTUs were identified that were characteristic for a particular ploidy level. Diploid and tetraploid species shared a large number of mycorrhizal fungi and the NMDS showed that there was no overall significant difference in fungal community composition between diploid, triploid and tetraploid species. These results contrast with findings of Těšitelová et al.26, who showed that diploid and tetraploid individuals sampled from different populations shared very few OTUs. Our results further indicated that variation in mycorrhizal communities was also not clearly related to the genomic composition of the orchids (see also Fig. S6). Although species of the D. sambucina group clearly separated from the other groups at the upper part of the plot, for the other species the distinction was less clear. Allotetraploids of D. fuchsii by D. incarnata origins were located somewhere intermediate between the two parental genomes, but the dispersion of allotetraploids along the axis perpendicular to the separation of D. fuchsii and D. incarnata was fairly large. Mycorrhizal communities of allotetraploids with D. maculata rather than D. fuchsii origins (D. sphagnicola and D. elata) were also not clearly related to each other, mainly due to the unclear position of D. elata, although D. maculata and D. sphagnicola tended to depart in the same direction.

Overall, our results showed that all sampled Dactylorhiza species associated with a large number of mycorrhizal OTUs encompassing multiple fungal genera, confirming previous research that mycorrhizal specificity in European terrestrial orchids tends to be low. Moreover, they also showed that ploidy level had no major impact on mycorrhizal communities in the sampled Dactylorhiza species. However, there was a clear and significant relationship between the habitats from which the orchid species were sampled and mycorrhizal community composition, suggesting that variation in mycorrhizal associations in orchid species is to some extent controlled by local environmental conditions.

Methods

Study species

The genus Dactylorhiza consists of a large group of species that are widely distributed across the boreal and temperate zones of Europe, Asia, North America and Northern parts of Africa and that occupy a wide range of habitats, including peat bogs, wet grasslands, dry meadows and forests16,17,18. Its taxonomical status is quite complex due to high morphological variation of many taxa and the numerous intra- and inter-genus hybrids18. Most Dactylorhiza species are summergreen with the leafy shoots appearing in early spring and mostly lasting until late summer – beginning of autumn. Observational studies have indicated that germination most likely takes place in late summer – beginning of autumn less than 3 months after seeds have been shed38. In agreement with Gymnadenia and Pseudorchis, but in contrast to the majority of other tuberous terrestrial orchids in Europe, the tubers are lobed or palmately divided. All species investigated so far have been shown to be dependent on mycorrhizal fungi20,21,22,23. Mycorrhizal colonization is mainly observed in the slender roots and sometimes in the extremities of the finger-like extensions of the tuber19,38.

The polyploid members of Dactylorhiza studied here have relatively recent origins and their relationships to diploid members of the genus have been elucidated by means of molecular data17,18,39,40. The two diploid species D. fuchsii and D. incarnata have been involved in the formation of most of the polyploid species. To facilitate comparison with polyploid members of the genus, their genomes are annotated with the letters F and I, respectively. The autotetraploid D. maculata is related to D. fuchsii, but must have originated from a diploid parental species somewhat divergent from the latter39,41 and its genome may be described as FM. The allotetraploid species D. alpestris, D. lapponica, D. majalis and D. praetermissa all have origins from parents similar to present day D. fuchsii and D. incarnata, and their genome compostions may thus be given as FFII17,18. The two allotetraploids D. sphagnicola and D. elata include one genome similar to that of present-day D. maculata39,42, and are best described by the genome formula FMFMII, but it should be observed that D. sphagnicola is probably considerably younger than D. elata18,43. The three diploids D. markusii, D. romana, and D. sambucina and the triploid D. insularis are more closely related to each other than to any other member of the genus40,44 and may be described by an S genome. Finally, the diploid D. viridis is probably sister to the rest of the genus45 and is best described by the genome composition VV.

Sampling

Sampling took place in May-June of 2010, 2011 and 2012. A total of 38 sites distributed across six European countries (Belgium, France, Italy, Portugal, Sweden and the United Kingdom) were sampled (Fig. S6; Table S2). At each site, root samples were collected, yielding a total of 114 sampled individuals from one to three populations of the 14 selected species. To minimize damage to the populations, three samples per population were taken. The sampled populations occupied a wide range of habitats on both acidic and alkaline soils, including Mediterranean grasslands and forests (D. sambucina, D. romana, D. insularis and D. markusii), peat bogs (D. sphagnicola, D. maculata), wetlands (D. fuchsii, D. majalis, D. viridis, D. elata), coastal habitats (D. praetermissa, D. incarnata) and alpine-boreal habitats (D. alpestris and D. lapponica).

Molecular assessment of the mycorrhizal fungi

All roots were surface sterilized (30 s submergence in 1% sodium hypochlorite, followed by three 30 s rinse steps in sterile distilled water) and microscopically checked for mycorrhizal colonization. Subsequently, DNA was extracted from 0.5 g mycorrhizal root fragments using the UltraClean Plant DNA Isolation Kit as described by the manufacturer (Mo Bio Laboratories Inc., Solana Beach, CA, USA). Amplicon libraries were created using the primers ITS1OF-C (AACTCGGCCATTTAGAGGAAGT)/ITS1OF-T (AACTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGT) and ITS4OF (5′-GTTACTAGGGGAATCCTTGTT-3′)46. All individuals per species were assigned unique MID (Multiplex Identifier) barcode sequences according to the guidelines for 454 GS-FLX+ Titanium Lib-L sequencing. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification was performed in duplicate in a 25 μl reaction volume containing 0.15 mM of each dNTP, 0.5 μM of each primer, 1 U Titanium Taq DNA polymerase, 1X Titanium Taq PCR buffer (Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA, USA), and 10 μl of DNA extract. PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation of 2 min at 94 °C followed by 30 cycles of 45 s at 94 °C, 45 s at 60 °C, and 45 s at 72 °C. After resolving the amplicons by agarose gel electrophoresis, amplicons within the appropriate size range (700 to 1000 bp) were cut from the gel and purified using the Qiaquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Hamburg, Germany). Purified dsDNA amplicons were quantified using the Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen) and pooled in equimolar quantities of 1.00E + 10 molecules per sample, resulting in two amplicon libraries designed with consideration to the recommendations of Lindahl et al.47, each representing one of the two PCR replicates. The quality of the amplicon libraries was assessed using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 and high sensitivity DNA chip (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany). Each amplicon library was loaded onto 1/8th of a 454 Pico Titer Plate (PTP). Pyrosequencing was performed using the Roche GS FLX+ instrument and Titanium chemistry using flow pattern B and software version 2.9 according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany).

Data analysis

Fungal diversity and community composition

Sequences obtained from the 454 pyrosequencing run were assigned to the appropriate sample based on both barcode and primer sequences, allowing zero discrepancies, and were subsequently trimmed from the barcodes and primers using CUTADAPT 1.048. As GS-FLX+ instrument flow pattern B minimizes the necessity for post-run denoising, sequences were trimmed based on a minimum Phred score of 30 (base call accuracy of 99.9%) averaged over a 50 bp moving window and sequences with ambiguous base calls or homopolymers longer than 8 nucleotides were rejected, as were chimeric sequences detected by the UCHIME chimera detection program (de novo algorithm)49. Sequences which passed all quality control procedures were used as the basis for all further analyses. Sequence lengths were set to 350 nucleotides. For further analysis, sequence data obtained for both PCR replicates were combined for each sample.

Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) were determined using UPARSE50, wherein sequences exceeding 97% sequence homology were clustered into the same OTU. OTUs representing only one or two sequences in the whole dataset (global singletons or doubletons) were removed from further analysis as it has been shown that this improves the accuracy of diversity estimates51. The remaining OTUs were assigned taxonomic identities to the highest taxonomic rank possible/family level based on manual screening of the top 10 BLAST52 results of representative sequences (as indicated by UPARSE) using GenBank53, including uncultured/environmental entries. Although there are reference sequence databases available (e.g. UNITE), preliminary analyses indicated that sequences corresponding to known orchid mycorrhizal sequences were only marginally represented. Finally, OTUs were manually screened for possible orchid-associating mycorrhizal families based on the data provided in Table 12.1 in Dearnaley et al.54. Only OTUs that were detected on orchid roots and had a high BLAST identity (>90%) to known orchid-associating mycorrhizal families were retained for further analysis.

Phylogenetic analyses

Separate phylogenetic analyses were performed with the OTUs that were assigned to Tulasnellaceae, Ceratobasidiaceae and Sebacinales. ITS sequence data of representatives of these groups and appropriate outgroups were downloaded from GenBank. Alignments were build using the MAFFT v.6.814b alignment tool55 implemented in Geneious Pro v5.5.6 (Biomatters, New Zealand). The GTR + I + G substitution model was selected to best fit for all four datasets using jModetest 2.1.556 under the Akaike Information Criterion. Phylogenetic analyses were performed under the Maximum Likelihood optimality criterion with RAxML v8.057. Clade support was estimated by non-parametric bootstrap analyses on 500 pseudo-replicate data sets.

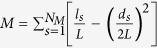

Ploidy, habitat and mycorrhizal communities

Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) was used to visualize differences in mycorrhizal communities across species. To test the hypothesis that fungal community composition differed between diploid and polyploid (triploid and tetraploid) species or between habitats, we used multivariate permutational analysis of variance using the adonis function of the vegan package58 in R. We also tested the hypothesis that the network of interactions between Dactylorhiza species and associating mycorrhizal fungi was significantly modular and that the identified modules can be brought back to differences in ploidy levels or habitats from which the species were sampled. To this end, we used the simulated annealing algorithm developed by Guimerà & Amaral59. The algorithm was specifically designed to identify modules whose nodes have the majority of their links inside their own module and provides an index of modularity  , where NM is the number of modules, L represents the number of links in the network, ls is the number of links between nodes in module s, and ds is the sum of the number of links of the nodes in module s. M values vary between 0 and −1/NM and measure the extent to which species have more links than expected if linkage is random. To determine the significance of the observed modularity index, 999 random networks with the same species degree distribution as the original network were constructed and the observed modularity index was compared with indices from random networks59. Finally, we used Species Indicator Analysis to investigate whether some mycorrhizal fungi were significantly associated with a particular habitat type. We used the multipatt function in the R package indicspecies to define indicator species of both individual habitats and combinations of habitats60.

, where NM is the number of modules, L represents the number of links in the network, ls is the number of links between nodes in module s, and ds is the sum of the number of links of the nodes in module s. M values vary between 0 and −1/NM and measure the extent to which species have more links than expected if linkage is random. To determine the significance of the observed modularity index, 999 random networks with the same species degree distribution as the original network were constructed and the observed modularity index was compared with indices from random networks59. Finally, we used Species Indicator Analysis to investigate whether some mycorrhizal fungi were significantly associated with a particular habitat type. We used the multipatt function in the R package indicspecies to define indicator species of both individual habitats and combinations of habitats60.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Jacquemyn, H. et al. Habitat-driven variation in mycorrhizal communities in the terrestrial orchid genus Dactylorhiza. Sci. Rep. 6, 37182; doi: 10.1038/srep37182 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Bruno Cachapa Bailarote and Agnieszka Deja for help with field work and molecular analyses and the reviewers and Editor for helpful comments. This research was supported by the European Research Council (ERC starting grant 260601 – MYCASOR awarded to HJ).

Footnotes

Author Contributions H.J. designed the research; H.J., D.T., R.B. and M.H. collected the data; M.W. and B.L. performed the molecular analyses; H.J., M.W. and V.S.F.T.M. analyzed the data; HJ wrote the first draft of the manuscript; all authors reviewed and approved the final draft.

References

- Bernard N. Recherches experimentales sur les orchidées. Revue Gén. Bot. 16, 405–451 (1904). [Google Scholar]

- Burgeff H. Samenkeimung der Orchideen (Gustaf Fisher, Jena, 1936). [Google Scholar]

- McCormick M. K. & Jacquemyn H. What constrains the distribution of orchid populations? New Phytol. 202, 392–400 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemyn H. et al. A spatially explicit analysis of seedling recruitment in the terrestrial orchid Orchis purpurea. New Phytol. 176, 448–459 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waud M., Wiegand T., Brys R., Lievens B. & Jacquemyn H. Nonrandom seedling establishment corresponds with distance dependent decline in mycorrhizal abundance in two terrestrial orchids. New Phytol. 211, 255–264 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemyn H. et al. Co-existing orchid species have distinct mycorrhizal communities and display strong spatial segregation. New Phytol. 202, 616–627 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peay K. G., Bidartondo M. I. & Arnold A. E. Not every fungus is everywhere: scaling to the biogeography of fungal-plant interactions across roots, shoots and ecosystems. New Phytol. 185, 878–882 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norros V., Penttila R., Suominin M. & Ovaskainen O. Dispersal may limit the occurrence of specialist wood decay fungi already at small spatial scales. Oikos 121, 961–974 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Toljander J. F., Eberhardt U., Toljander Y. K., Paul L. R. & Taylor A. F. S. Species composition of an ectomycorrhizal fungal community along a local nutrient gradient in a boreal forest. New Phytol. 170, 873–883 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peay K. G. et al. Lack of host specificity leads to independent assortment of dipterocarps and ectomycorrhizal fungi across a soil fertility gradient. Ecol. Lett. 18, 807–816 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waud M., Busschaert P., Lievens B. & Jacquemyn H. Specificity and localised distribution of mycorrhizal fungi in the soil may contribute to co-existence of orchid species. Fungal Ecol. 20, 155–165 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Pandey M., Sharma J., Taylor D. L. & Yadon V. L. A. narrowly endemic photosynthetic orchid is non-specific in its mycorrhizal associations. Mol. Ecol. 22, 2341–2354 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemyn H., Waud M., Merckx V. S. F. T., Lievens B. & Brys R. Mycorrhizal diversity, seed germination and long-term changes in population size across nine populations of the terrestrial orchid Neottia ovata. Mol. Ecol. 24, 3269–3280 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oja J., Kohout P., Tedersoo L., Kull T. & Kõljalg U. Temporal patterns of orchid mycorrhizal fungi in meadows and forests as revealed by 454 pyrosequencing. New Phytol. 205, 1608–1618 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemyn H., Waud M., Lievens B. & Brys R. Differences in mycorrhizal communities between Epipactis palustris, E. helleborine and its presumed sister species E. neerlandica Ann. Bot. 118, 105–114 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delforge P. Orchids of Europe, North Africa and the Middle East (A&C Black, London, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- Devos N., Raspé O., Oh S. H., Tyteca D. & Jacquemart A.-L. The evolution of Dactylorhiza (Orchidaceae) allotetraploid complex: Insights from nrDNA sequences and cpDNA PCR-RFLP data. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 38, 767–778 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillon Y. et al. Evolution and temporal diversification of western European polyploidy species complexes in Dactylorhiza (Orchidaceae). Taxon 56, 1185–1208 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen H. N. Terrestrial orchids: from seed to mycotrophic plant (Cambridge University Press, New York, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen K. A., Taylor D. L., Kjoller R., Rasmussen H. N. & Rosendahl S. Identification of mycorrhizal fungi from single pelotons of Dactylorhiza majalis (Orchidaceae) using single-strand conformation polymorphism and mitochondrial ribosomal large subunit DNA sequences. Mol. Ecol. 10, 2089–2093 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailarote B. C., Lievens B. & Jacquemyn H. Does mycorrhizal specificity affect orchid decline and rarity? Am. J. Bot. 99, 1655–1665 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemyn H., Deja A., De hert K., Cachapa Bailarote B. & Lievens B. Variation in mycorrhizal associations with Tulasnelloid fungi among populations of five Dactylorhiza species. PLoS One 7, e42212 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shefferson R. P., Kull T. & Tali K. Mycorrhizal interactions of orchids colonizing Estonian mine tailings hills. Am. J. Bot. 95, 156–164 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averyanov L. V. In Orchid Biology: Reviews and Perspectives, vol. V. (ed. Arditti J. ) Ch. 5, 159–206 (Timber Press, 1990). [Google Scholar]

- Hedrén M. Systematics of the Dactylorhiza euxina/incarnata/maculata polyploid complex (Orchidaceae) in Turkey: evidence from allozyme data. Plant Syst. Evol. 229, 23–44 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Těšitelová T. et al. Ploidy-specific symbiotic interactions: divergence of mycorrhizal fungi between cytotypes of the Gymnadenia conopsea group (Orchidaceae). New Phytol. 199, 1022–1033 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girlanda M. et al. Photosynthetic Mediterranean meadow orchid feature partial mycoheterotrophy and specific mycorrhizal associations. Am. J. Bot. 98, 1148–1163 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selosse M. A. et al. Sebacinales are common mycorrhizal associates. New Phytol. 174, 864–878 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiß M. et al. Sebacinales everywhere: previously overlooked ubiquitous fungal endophytes. PLoS One 6, e16793 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Heijden M. G. A., Martin F. M., Selosse M.-A. & Sanders I. R. Mycorrhizal ecology and evolution: the past, the present, and the future. New Phytol. 205, 1406–1423 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemyn H., Honnay O., Cammue B. P. A., Brys R. & Lievens B. Low specificity and nested subset structure characterize mycorrhizal associations in five closely related species of the genus Orchis. Mol. Ecol. 19, 4086–4095 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemyn H. et al. Analysis of network architecture reveals phylogenetic constraints on mycorrhizal specificity in the genus Orchis (Orchidaceae). New Phytol. 192, 518–528 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Těšitelová T. et al. Two widespread green Neottia species (Orchidaceae) show mycorrhizal preference for Sebacinales in various habitats and ontogenetic stages. Mol. Ecol. 24, 1122–1134 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick M. K. et al. Abundance and distribution of Corallorhiza odontorhiza reflects variations in climate and ectomycorrhizae. Ecol. Monogr. 79, 619–635 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Bidartondo M. I. & Read D. J. Fungal specificity bottlenecks during orchid germination and development. Mol. Ecol. 17, 3707–3716 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemyn H., Brys R., Waud M., Busschaert P. & Lievens B. Mycorrhizal networks and coexistence in species-rich orchid communities. New Phytol. 206, 1127–1134 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Laere K. et al. Influence of ploidy level on morphology, growth and drought susceptibility in Spathiphyllum wallisii. Acta Physiol. Plant. 33, 1149–1156 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Dijk E., Willems J. H. & Van Andel J. Nutrient responses as a key factor to the ecology of orchid species. Acta Bot. Neerl. 46, 339–363 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Hedrén M., Fay M. & Chase M. W. Amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLP) reveal details of polyploid evolution in Dactylorhiza (Orchidaceae). Am. J. Bot. 88, 1868–1880 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos N., Tyteca D., Raspé O., Wesselingh R. A. & Jacquemart A.-L. Patterns of chloroplast diversity among western European Dactylorhiza species (Orchidaceae). Plant Syst. Evol. 243, 85–97 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Devos N., Oh S.-H., Raspé O., Jacquemart A.-L. & Manos P. S. Nuclear ribosomal DNA sequence variation and evolution of spotted marsh-orchids (Dactylorhiza maculata group). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 36, 568–580 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrén M. Plastid DNA variation in the Dactylorhiza incarnata/maculata polyploid complex and the origin of allotetraploid D. sphagnicola (Orchidaceae). Mol. Ecol. 12, 2669–2680 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrén M. Plastid DNA haplotype variation in Dactylorhiza incarnata (Orchidaceae): evidence for multiple independent colonization events into Scandinavia. Nord. J. Bot. 27, 69–80 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen H. Æ. Systematics and evolution of the Dactylorhiza romana/sambucina polyploid complex (Orchidaceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 152, 405–434 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Devos N., Raspé O., Jacquemart A.-L. & Tyteca D. On the monophyly of Dactylorhiza Necker ex Nevski (Orchidaceae): is Coeloglossum viride (L.) Hartman a Dactylorhiza? Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 152, 261–269 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D. L. & McCormick M. K. Internal transcribed spacer primers and sequences for improved characterization of basidiomycetous orchid mycorrhizas. New Phytol. 177, 1020–1033 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl B. D. et al. Fungal community analysis by high‐throughput sequencing of amplified markers–a user’s guide. New Phytol. 199, 288–299 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet Journal 17, 10–12 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C., Haas B. J., Clemente J. C., Quince C. & Knight R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27, 2194–2200 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10, 996 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihrmark K. et al. New primers to amplify the fungal ITS2 region – evaluation by 454-sequencing of artificial and natural communities. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 82, 666–677 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Gish G. W., Miller W., Myers E. W. & Lipman D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson D. A., Karsch-Mizrachi I., Lipman D. J., Ostell J. & Wheeler D. L. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 25–30 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearnaley J. W. D., Martos F. & Selosse M. A. In Fungal Associations 2nd edn (ed. Hock B. ) Ch. 12, 207–230 (Springer-Verlag, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Misawa K., Kuma K. & Miyata T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3059–3066 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darriba D., Taboada G. L., Doallo R. & Posada D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods 9, 772 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1313–1313 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen J. et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.3-1 (2015).

- Guimerà R. & Amaral L. A. N. Functional cartography of complex metabolic networks. Nature 433, 895–900 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Cáceres M., Legendre P. & Moretti M. Improving indicator species analysis by combining groups of sites. Oikos 119, 1674–1684 (2010). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.