Abstract

Benzothiazole, a microbial secondary metabolite, has been demonstrated to possess fumigant activity against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, Ditylenchus destructor and Bradysia odoriphaga. However, to facilitate the development of novel microbial pesticides, the mode of action of benzothiazole needs to be elucidated. Here, we employed iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomics analysis to investigate the effects of benzothiazole on the proteomic expression of B. odoriphaga. In response to benzothiazole, 92 of 863 identified proteins in B. odoriphaga exhibited altered levels of expression, among which 14 proteins were related to the action mechanism of benzothiazole, 11 proteins were involved in stress responses, and 67 proteins were associated with the adaptation of B. odoriphaga to benzothiazole. Further bioinformatics analysis indicated that the reduction in energy metabolism, inhibition of the detoxification process and interference with DNA and RNA synthesis were potentially associated with the mode of action of benzothiazole. The myosin heavy chain, succinyl-CoA synthetase and Ca+-transporting ATPase proteins may be related to the stress response. Increased expression of proteins involved in carbohydrate metabolism, energy production and conversion pathways was responsible for the adaptive response of B. odoriphaga. The results of this study provide novel insight into the molecular mechanisms of benzothiazole at a large-scale translation level and will facilitate the elucidation of the mechanism of action of benzothiazole.

Chinese chive (Allium tuberosum Rottler) is a hardy perennial herbaceous vegetable of high economic value in several regions of southeastern and eastern Asia1,2. A major factor restricting Chinese chive production is the chive maggot, Bradysia odoriphaga (Diptera: Sciaridae)3,4. The larvae feed on the roots and bulbs of chives, making it difficult to control them using common strategies, and cause more than 50% of production losses in the absence of insecticidal protection3. One of the most prevalent management practices for controlling B. odoriphaga is the application of synthetic insecticides (such as organophosphates, carbamates, and neonicotinoids) in China and elsewhere5. However, the control efficacy is unsatisfactory because of the dilution effects of soil and water on pesticides and the overlapping generations of B. odoriphaga6. This challenge has led to the excessive application of chemical insecticides, which has resulted in the development of insecticide resistance in B. odoriphaga and high residue levels being left on marketed Chinese chives4. Reducing the application of these insecticides will require the development of novel effective insecticides as an alternative to conventional ones.

Benzothiazole is one component of the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) derived from microbial secondary metabolites7,8. This compound has been demonstrated to be a fumigant that can be used in the control of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum9, Ditylenchus destructor10, and Tribolium castaneum11. In our previous study, we found that benzothiaz ole exhibited fumigation toxicity to all stages of B. odoriphaga12, decreased the fecundity of female adults, and prolonged the developmental time of B. odoriphaga13, thus indicating its potential as a fumigant for the control of this pest. Moreover, the respiratory rate of B. odoriphaga was significantly increased in the beginning of benzothiazole treatment, and as the fumigation time was extended, the respiratory rate was significantly reduced12. These results indicate that benzothiazole is not a respiratory inhibitor. In addition, benzothiazole can cause a significant reduction in food consumption and can decrease nutrient accumulation in B. odoriphaga larvae by disrupting the activity of digestive enzymes14. Most studies of benzothiazole as a broad-spectrum fumigant against pests have focused on the determination of its biological activity. However, the molecular mechanism of action of benzothiazole remains poorly understood, and understanding this mechanism will be helpful for the development of new pesticides and the control of these pests in the future.

In recent years, proteomics analysis has emerged as a powerful method for studying changes in protein expression profiles at the cellular level in response to various stresses15,16,17,18,19. This approach has been widely used to identify the modes of action of some drugs and in target discovery20,21,22. A wide range of studies has been conducted utilizing iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomic technology23,24,25,26,27 because of its high proteome coverage, high sensitivity and labeling efficiency. For instance, Pang et al. demonstrated that the mechanism of action of pyrimorph in Phytophthora capsici involves the inhibition of cell wall biosynthesis using iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomics24. Thus, the use of proteomics approaches is useful for elucidating the mode of action of novel pesticides.

In the present study, we utilized an iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomic approach to analyze proteomic changes in B. odoriphaga in response to benzothiazole. Our goals were to identify proteins that are differentially expressed in B. odoriphaga following treatment with benzothiazole. An analysis of these proteins provides important insights into the mechanism of action of benzothiazole.

Results

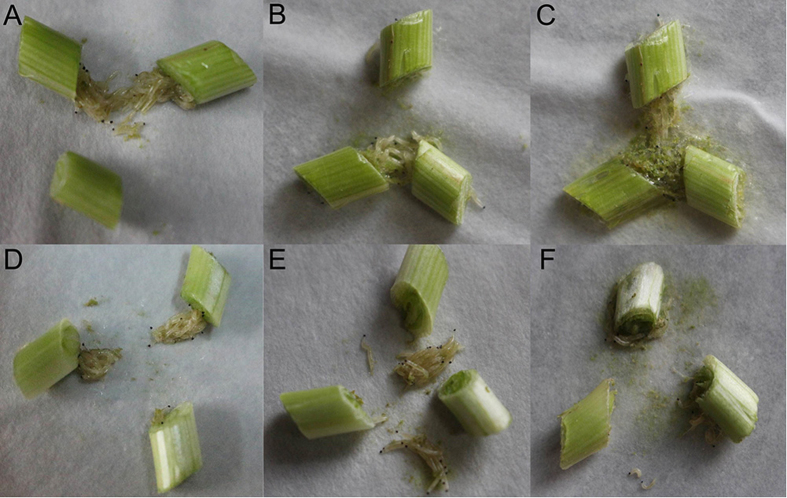

Motility and ingestion of B. odoriphaga

As shown in Fig. 1, the effects of benzothiazole on the motility and ingestion of B. odoriphaga were observed at 0 h, 6 h and 24 h after treatment. At the beginning of fumigation (0 h), larvae gathered near the Chinese chive rhizomes and ingested the rhizomes both in the distilled water (Fig. 1A) and the benzothiazole (Fig. 1D) treatments. Following distilled water and benzothiazole treatment for 6 h, the larvae drilled into and ingested the fresh Chinese chive rhizomes in the distilled water treatment (Fig. 1B). However, in the benzothiazole treatment, the larvae gathered around the rhizomes but exhibited almost no ingestion or activity (Fig. 1E). Following distilled water treatment for 24 h, the larvae drilled into and ingested the rhizomes, surrounded by the secretion of silk thread and food debris (Fig. 1C). After benzothiazole treatment for 24 h, the surviving larvae had adapted and recovered their ingestion and movement (Fig. 1F).

Figure 1.

The motility and ingestion of B. odoriphaga after treatment with distilled water for 0 h (A), 6 h (B) and 24 h (C) and with the LC30 of benzothiazole for 0 h (D), 6 h (E) and 24 h (F).

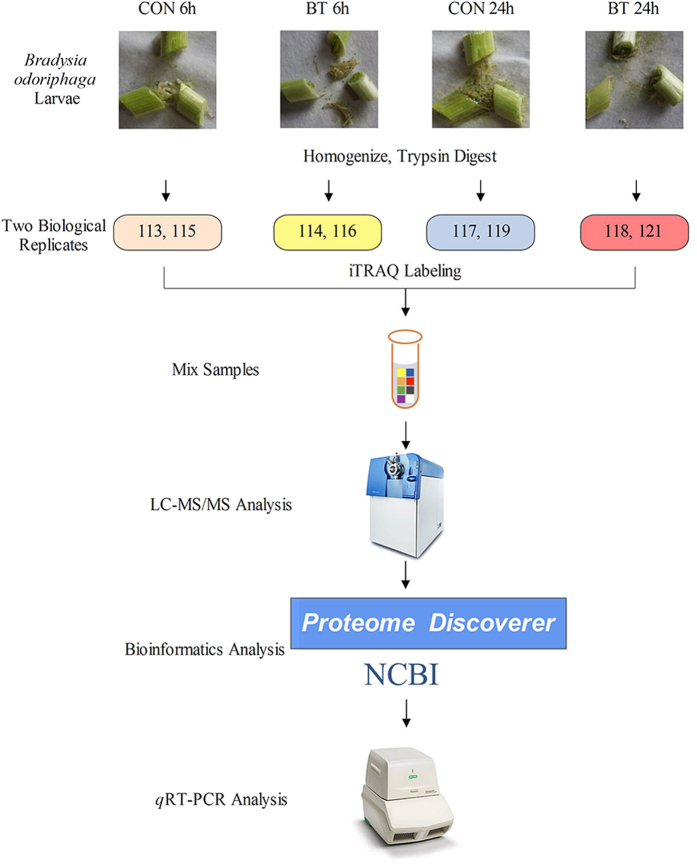

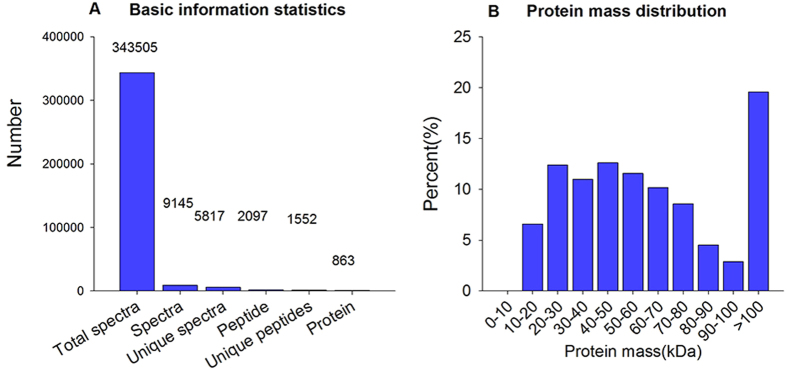

Overview of the quantitative proteomics analysis

Figure 2 shows the workflow of iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomic analysis and some proteins that were verified by qRT-PCR in this study. A total of 863 proteins were identified on the basis of 9,145 highly confident spectra, of which 1,552 peptides were unique (Fig. 3A). In terms of protein mass distribution, good coverage was obtained for a wide range for proteins larger than 10 kDa (Fig. 3B).

Figure 2. Experimental design and schematic diagram of the workflow of this study.

CON: control, BT: benzothiazole.

Figure 3.

(A) Spectra, peptides and proteins identified from iTRAQ proteomics by searching against the Nematocera database. (B) Molecular weight distribution of the proteins that were identified from the iTRAQ analysis of B. odoriphaga.

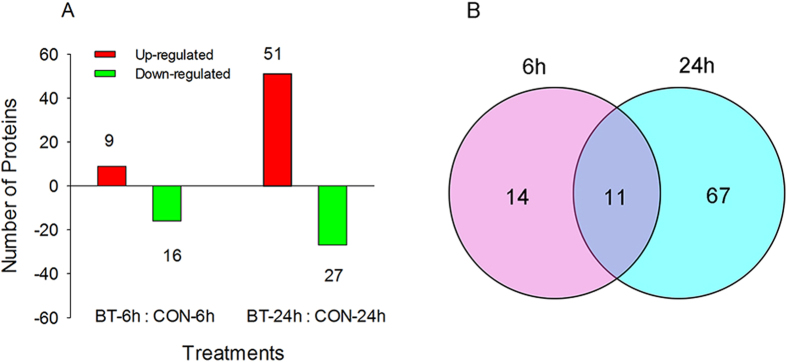

Using a threshold of a 1.2-fold change in abundance (±) and a p-value less than 0.05 (compared to the distilled water-treated larvae), 92 unique proteins were found to have significantly changed in abundance when B. odoriphaga larvae were treated with benzothiazole for 6 h and 24 h (Tables 1, 2, 3, , , , ). Of these unique proteins, the abundance of 25 (9 up-regulated and 16 down-regulated) was changed significantly after 6 h, and the abundance of 78 (51 up-regulated and 27 down-regulated) was changed significantly after 24 h (Fig. 4A). Among these proteins with altered abundance, 11 were shared between 6 h and 24 h, whereas the more responsive proteins were unique to the different treatment times (Fig. 4B).

Table 1. Differentially expressed proteins identified by the iTRAQ analysis of B. odoriphaga that are related to the action mechanism of benzothiazole.

| No. | Accession ID | Description | Unique Peptide | Scorea | Coverage (%)b | Fold change (Mean ± SD)c BT/CONd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrate transport and metabolism | ||||||

| 1 | gi|563354894 | triose-phosphate isomerase [Mayetiola destructor] | 1 | 305 | 11.3 | 0.726 ± 0.368 |

| Cytoskeleton | ||||||

| 2 | gi|167862461 | actin-2 [Culex quinquefasciatus] | 1 | 5218 | 38.8 | 1.201 ± 0.216 |

| 3 | gi|197260680 | calponin/transgelin [Simulium vittatum] | 1 | 289 | 7.4 | 1.152 ± 0.119 |

| Energy production and conversion | ||||||

| 4 | gi|157113604 | vacuolar ATP synthase subunit H [Aedes aegypti] | 1 | 140 | 7.4 | 0.765 ± 0.252 |

| General function prediction only | ||||||

| 5 | gi|545920623 | putative transporter abc superfamily [Corethrella appendiculata] | 2 | 47 | 2.1 | 0.853 ± 0.117 |

| 6 | gi|157110428 | developmentally regulated GTP-binding protein 1 [Aedes aegypti] | 2 | 117 | 6.3 | 0.694 ± 0.017 |

| Inorganic ion transport and metabolism | ||||||

| 7 | gi|157127037 | superoxide dismutase [Aedes aegypti] | 1 | 94 | 6.5 | 0.807 ± 0.002 |

| Lipid transport and metabolism | ||||||

| 8 | gi|545918281 | putative peroxisomal 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase [Corethrella appendiculata] | 3 | 183 | 4.4 | 0.869 ± 0.103 |

| Nucleotide transport and metabolism | ||||||

| 9 | gi|157103945 | dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase [Aedes aegypti] | 1 | 92 | 1.2 | 0.860 ± 0.046 |

| 10 | gi|94468478 | nucleoside diphosphate kinase [Aedes aegypti] | 1 | 99 | 17.3 | 0.786 ± 0.020 |

| Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones | ||||||

| 11 | gi|157131967 | prohibitin [Aedes aegypti] | 5 | 350 | 14.1 | 0.906 ± 0.128 |

| Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis | ||||||

| 12 | gi|94468404 | 40 S ribosomal protein S4 [Aedes aegypti] | 1 | 140 | 7.3 | 0.826 ± 0.030 |

| Uncharacterized | ||||||

| 13 | gi|545917000 | putative oligosaccharyltransferase gamma subunit [Corethrella appendiculata] | 2 | 124 | 7.3 | 0.895 ± 0.100 |

| 14 | gi|157361547 | 40 S ribosomal S30 protein-like protein [Phlebotomus papatasi] | 2 | 249 | 8.5 | 0.830 ± 0.035 |

Table 2. Differentially expressed proteins identified by the iTRAQ analysis of B. odoriphaga that are related to the stress response to benzothiazole.

| No. | Accession ID | Description | Unique Peptide | Score | Coverage (%) | Fold change (Mean ± SD) BT/CON |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 h | 24 h | ||||||

| Cytoskeleton | |||||||

| 15 | gi|167881575 | myosin heavy chain [Culex quinquefasciatus] | 2 | 6019 | 18.3 | 1.291 ± 0.062 | 1.825 ± 0.261 |

| Energy production and conversion | |||||||

| 16 | gi|563354922 | succinyl-CoA synthetase alpha [Mayetiola destructor] | 6 | 441 | 23.6 | 0.864 ± 0.180 | 1.439 ± 0.042 |

| General function prediction only | |||||||

| 17 | gi|524935491 | putative polyadenylate-binding protein rrm superfamily [Anopheles aquasalis] | 2 | 159 | 8.8 | 1.372 ± 0.107 | 3.031 ± 0.029 |

| Inorganic ion transport and metabolism | |||||||

| 18 | gi|158295513 | Calcium-transporting ATPase sarcoplasmic [Anopheles sinensis] | 2 | 2062 | 16 | 1.314 ± 0.035 | 3.379 ± 0.291 |

| Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones | |||||||

| 19 | gi|167880127 | 26 S protease regulatory subunit 6 A [Culex quinquefasciatus] | 5 | 239 | 18.2 | 0.698 ± 0.183 | 1.261 ± 0.010 |

| 20 | gi|167875398 | mitochondrial chaperone BCS1 [Culex quinquefasciatus] | 1 | 191 | 2.8 | 1.173 ± 0.115 | 0.559 ± 0.000 |

| 21 | gi|34867976 | N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor [Aedes aegypti] | 3 | 93 | 4.9 | 0.807 ± 0.141 | 0.685 ± 0.025 |

| Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism | |||||||

| 22 | gi|338841083 | cytochrome P450 9J28, partial [Aedes aegypti] | 1 | 55 | 2.1 | 0.830 ± 0.017 | 0.730 ± 0.092 |

| Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis | |||||||

| 23 | gi|545921305 | putative S3aE ribosomal protein [Corethrella appendiculata] | 2 | 105 | 10.1 | 1.292 ± 0.144 | 2.662 ± 0.804 |

| 24 | gi|524935628 | putative elongation factor 1-beta2 [Anopheles aquasalis] | 1 | 276 | 4 | 1.137 ± 0.103 | 1.968 ± 0.025 |

| Uncharacterized | |||||||

| 25 | gi|157135572 | profilin [Aedes aegypti] | 2 | 178 | 15.9 | 1.140 ± 0.181 | 2.278 ± 0.827 |

Table 3. Differentially expressed proteins identified by the iTRAQ analysis of B. odoriphaga that are related to the adaption response to benzothiazole.

| No. | Accession ID | Description | Unique Peptide | Score | Coverage (%) | Fold change (Mean ± SD) BT/CON |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino acid transport and metabolism | ||||||

| 26 | gi|54289246 | pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase, partial [Aedes aegypti] | 2 | 213 | 4.5 | 1.802 ± 0.147 |

| 27 | gi|284159519 | arginine kinase, partial [Coquillettidia perturbans] | 2 | 908 | 18.1 | 1.783 ± 0.105 |

| 28 | gi|157129677 | serine hydroxymethyltransferase [Aedes aegypti] | 1 | 78 | 2.9 | 1.350 ± 0.112 |

| 29 | gi|524934116 | putative aminopeptidase [Anopheles aquasalis] | 2 | 172 | 4.2 | 0.524 ± 0.052 |

| 30 | gi|545916496 | putative alanine aminotransferase [Corethrella appendiculata] | 2 | 39 | 3.1 | 0.854 ± 0.173 |

| Carbohydrate transport and metabolism | ||||||

| 31 | gi|157674465 | putative enolase [Lutzomyia longipalpis] | 2 | 1218 | 18.7 | 1.379 ± 0.096 |

| 32 | gi|545917538 | putative transaldolase, partial [Corethrella appendiculata] | 1 | 208 | 6.3 | 1.314 ± 0.233 |

| 33 | gi|563354904 | pyruvate kinase [Mayetiola destructor] | 8 | 928 | 17 | 1.201 ± 0.130 |

| 34 | gi|405132161 | glycogen phosphorylase [Belgica antarctica] | 3 | 248 | 5.5 | 0.841 ± 0.066 |

| Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis | ||||||

| 35 | gi|58376929 | Glucosamine–fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase [Anopheles gambiae] | 1 | 165 | 3.7 | 0.853 ± 0.146 |

| Cytoskeleton | ||||||

| 36 | gi|31210041 | Actin-related protein 3 [Drosophila melanogaster] | 4 | 284 | 12.9 | 0.749 ± 0.112 |

| Energy production and conversion | ||||||

| 37 | gi|313482947 | putative IgE binding protein, partial [Culicoides nubeculosus] | 1 | 318 | 23.8 | 1.569 ± 0.607 |

| 38 | gi|158300600 | Probable citrate synthase 1, mitochondrial [Aedes aegypti] | 2 | 430 | 14.8 | 1.548 ± 0.185 |

| 39 | gi|157132308 | ATP synthase beta subunit [Aedes aegypti] | 13 | 2473 | 36.9 | 1.529 ± 0.064 |

| 40 | gi|563354932 | malate dehydrogenase 1 [Mayetiola destrauctor] | 6 | 200 | 16.9 | 1.519 ± 0.266 |

| 41 | gi|157123846 | pyruvate carboxylase [Aedes aegypti] | 9 | 233 | 7.5 | 1.310 ± 0.063 |

| 42 | gi|545919823 | putative methylmalonate semialdehyde dehydrogenase [Corethrella appendiculata] | 2 | 139 | 7.1 | 1.241 ± 0.135 |

| 43 | gi|108878452 | ATP synthase subunit beta vacuolar [Aedes aegypti] | 10 | 570 | 28.6 | 1.231 ± 0.083 |

| General function prediction only | ||||||

| 44 | gi|56684613 | ADP ribosylation factor 79 F [Aedes aegypti] | 4 | 548 | 31.3 | 1.363 ± 0.192 |

| 45 | gi|545920491 | putative g protein [Corethrella appendiculata] | 5 | 234 | 13.2 | 1.355 ± 0.202 |

| 46 | gi|157136642 | ras-related protein Rab-7 [Aedes aegypti] | 3 | 130 | 15.4 | 1.184 ± 0.247 |

| 47 | gi|545918333 | putative gtpase ran/tc4/gsp1 nuclear protein [Corethrella appendiculata] | 5 | 328 | 28.5 | 1.156 ± 0.203 |

| Inorganic ion transport and metabolism | ||||||

| 48 | gi|14906173 | putative 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate synthetase, partial [Aedes aegypti] | 1 | 44 | 4.2 | 1.592 ± 0.011 |

| 49 | gi|157131369 | Na+/K+ ATPase alpha subunit [Aedes aegypti] | 10 | 619 | 19.8 | 1.505 ± 0.226 |

| Intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport | ||||||

| 50 | gi|545918815 | putative signal peptidase i [Corethrella appendiculata] | 3 | 233 | 18.9 | 0.729 ± 0.086 |

| Lipid transport and metabolism | ||||||

| 51 | gi|524934245 | putative microtubule associated complex [Anopheles aquasalis] | 3 | 110 | 13.2 | 1.262 ± 0.078 |

| 52 | gi|167874883 | 3-oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] reductase [Culex quinquefasciatus] | 1 | 104 | 4.7 | 1.271 ± 0.318 |

| Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones | ||||||

| 53 | gi|545920109 | putative 60 kda heat shock protein mitochondrial [Corethrella appendiculata] | 1 | 239 | 7.4 | 2.184 ± 0.233 |

| 54 | gi|108868487 | Small ubiquitin-related modifier 3 [Aedes aegypti] | 1 | 208 | 12.6 | 1.994 ± 0.868 |

| 55 | gi|157122974 | prohibitin [Aedes aegypti] | 5 | 144 | 18.4 | 1.976 ± 0.065 |

| 56 | gi|545916790 | putative atp-dependent lon protease, partial [Corethrella appendiculata] | 5 | 129 | 5.9 | 1.425 ± 0.366 |

| 57 | gi|2738077 | heat shock protein 60 [Culicoides variipennis] | 3 | 557 | 13.1 | 1.415 ± 0.105 |

| 58 | gi|157106603 | 26 S protease regulatory subunit S10b [Aedes aegypti] | 5 | 273 | 13.2 | 1.393 ± 0.136 |

| 59 | gi|89212800 | heat shock cognate 70 [Rhynchosciara americana] | 13 | 1725 | 39 | 1.200 ± 0.040 |

| 60 | gi|157131453 | 26 S protease regulatory subunit [Aedes aegypti] | 1 | 121 | 14.2 | 0.863 ± 0.151 |

| 61 | gi|108870669 | Rab GDP-dissociation inhibitor [Aedes aegypti] | 5 | 130 | 11.3 | 0.905 ± 0.103 |

| Replication, recombination and repair | ||||||

| 62 | gi|167865143 | ebna2 binding protein P100 [Culex quinquefasciatus] | 2 | 96 | 2.6 | 0.806 ± 0.016 |

| Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism | ||||||

| 63 | gi|157115283 | fatty acid synthase [Aedes aegypti] | 2 | 295 | 1.9 | 1.835 ± 0.480 |

| 64 | gi|584594454 | cytochrome P450 6FV2 [Chironomus kiiensis] | 1 | 114 | 4.6 | 0.748 ± 0.190 |

| Signal transduction mechanisms | ||||||

| 65 | gi|58396588 | 14-3-3 protein epsilon [Drosophila melanogaster] | 6 | 1263 | 22.7 | 0.754 ± 0.050 |

| 66 | gi|94468532 | myosin light chain [Aedes aegypti] | 3 | 107 | 19.7 | 0.822 ± 0.023 |

| Transcription | ||||||

| 67 | gi|58378742 | Nascent polypeptide-associated complex subunit alpha [Drosophila melanogaster] | 3 | 358 | 18 | 1.402 ± 0.156 |

| Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis | ||||||

| 68 | gi|170030017 | 40 S ribosomal protein S23 [Culex quinquefasciatus] | 2 | 338 | 15.4 | 1.681 ± 0.129 |

| 69 | gi|568255436 | hypothetical protein AND_004054 [Anopheles darlingi] | 2 | 91 | 3.4 | 1.668 ± 0.091 |

| 70 | gi|329669248 | 60 S acidic ribosomal protein P1 [Simulium guianense] | 1 | 781 | 14.5 | 1.649 ± 0.204 |

| 71 | gi|29839631 | 60 S ribosomal protein L23 [Aedes aegypti] | 4 | 538 | 31.4 | 1.584 ± 0.416 |

| 72 | gi|157674443 | 60 S acidic ribosomal protein P0-like protein [Lutzomyia longipalpis] | 1 | 635 | 22.4 | 1.535 ± 0.103 |

| 73 | gi|58392254 | 60 S ribosomal protein L12 [Mus musculus] | 3 | 160 | 18.2 | 1.433 ± 0.129 |

| 74 | gi|545920235 | putative elongation factor 2, partial [Corethrella appendiculata] | 2 | 623 | 12.8 | 1.155 ± 0.186 |

| 75 | gi|56809869 | ribosomal protein S9 [Aedes albopictus] | 6 | 189 | 23.1 | 0.697 ± 0.145 |

| 76 | gi|545920339 | putative ribosomal protein l32 [Corethrella appendiculata] | 3 | 436 | 16.4 | 0.739 ± 0.179 |

| 77 | gi|56199506 | ribosomal protein L27A, partial [Culicoides sonorensis] | 2 | 398 | 13.2 | 0.777 ± 0.046 |

| 78 | gi|401715292 | 60 s ribosomal protein L15, partial [Nyssomyia intermedia] | 2 | 200 | 20.9 | 0.789 ± 0.287 |

| 79 | gi|157361525 | 40 S ribosomal protein S15-like protein [Phlebotomus papatasi] | 3 | 299 | 23.1 | 0.806 ± 0.095 |

| 80 | gi|545920337 | putative 60 s acidic ribosomal protein p0 [Corethrella appendiculata] | 1 | 576 | 21.3 | 0.823 ± 0.240 |

| 81 | gi|269146822 | 60 s ribosomal protein L10, partial [Simulium nigrimanum] | 2 | 179 | 11.4 | 0.879 ± 0.091 |

| Uncharacterized | ||||||

| 82 | gi|157131827 | tropomyosin invertebrate [Aedes aegypti] | 1 | 176 | 25.2 | 4.289 ± 2.567 |

| 83 | gi|157127892 | paramyosin, long form [Aedes aegypti] | 1 | 146 | 3.9 | 3.158 ± 0.843 |

| 84 | gi|74920601 | ADP, ATP carrier protein 2 [Anopheles gambiae] | 1 | 628 | 24.3 | 2.057 ± 0.155 |

| 85 | gi|108884438 | AAEL000311-PA [Aedes aegypti] | 1 | 174 | 1.7 | 1.474 ± 0.411 |

| 86 | gi|407379599 | gamma-glutamylcystein synthase [Chironomus riparius] | 1 | 79 | 2.4 | 1.378 ± 0.166 |

| 87 | gi|167872478 | mitochondrial processing peptidase beta subunit [Culex quinquefasciatus] | 2 | 57 | 2.6 | 1.346 ± 0.305 |

| 88 | gi|404553129 | prophenoloxidase 6, partial [Anopheles sinensis] | 2 | 60 | 7.5 | 0.695 ± 0.052 |

| 89 | gi|157109554 | titin [Aedes aegypti] | 1 | 354 | 2.4 | 0.736 ± 0.095 |

| 90 | gi|157117953 | glutamate cysteine ligase [Aedes aegypti] | 1 | 112 | 2.3 | 0.805 ± 0.250 |

| 91 | gi|158295341 | AGAP006103-PC [Anopheles gambiae] | 1 | 202 | 7.5 | 0.850 ± 0.150 |

| 92 | gi|108884446 | AAEL000339-PA [Aedes aegypti] | 1 | 135 | 2.1 | 0.876 ± 0.155 |

Figure 4.

(A) The number of up- and down-regulated proteins of B. odoriphaga after treatment with benzothiazole for 6 and 24 h. BT: benzothiazole; CON: control. (B) Venn diagram showing the overlap between the differentially expressed proteins of B. odoriphaga at 6 and 24 h after benzothiazole treatment.

Proteins related to the mode of action of benzothiazole

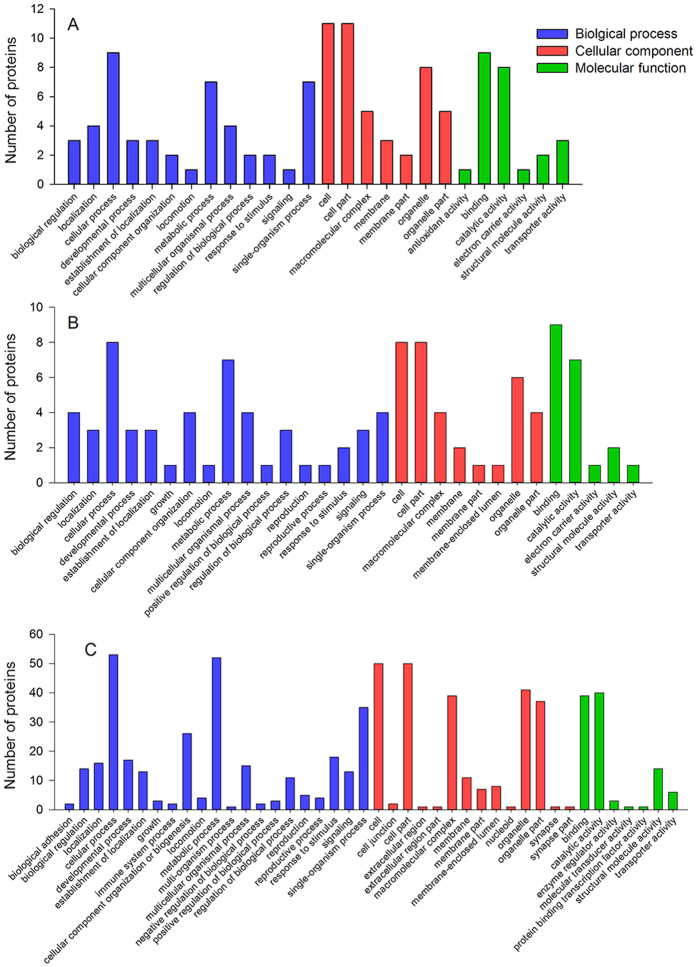

Proteins that were differently expressed under benzothiazole treatment at 6 h but not at 24 h were considered to be related to the mode of action of benzothiazole on B. odoriphaga. In total, 14 proteins were differentially expressed, of which 2 were up-regulated and 12 were down-regulated (Table 1). GO enrichment analysis was used to categorize these proteins into biological processes, cellular components and molecular functions. The results are presented in Fig. 5A. The categories affected by benzothiazole mainly involved metabolic process, cellular process, single-organism process, binding, catalytic activity, and transporter activity. A COG analysis classified these 14 proteins into 10 functional groups, including a range of metabolic pathways, such as carbohydrate metabolism, lipid metabolism, nucleotide metabolism and inorganic ion metabolism, and cytoskeleton, energy production and conversion, and general function predictions (Table 1).

Figure 5. Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the differentially expressed proteins.

The proteins are grouped into three GO terms: biological process, cellular component, and molecular function. (A) Proteins related to the action mechanism; (B) proteins related to the stress response; (C) proteins related to the adaption response.

Proteins related to the stress response of B. odoriphaga to benzothiazole

The B. odoriphaga proteins that were significantly changed by the benzothiazole treatment at 6 and 24 h were related to the stress response. Eleven differentially expressed proteins were identified, of which 6 were up-regulated, 2 were down-regulated and 3 were up- or down-regulated at different times (Table 2). GO analysis was conducted to categorize these proteins, and the most-assigned classifications included metabolic process, cellular process, single-organism process, binding, catalytic activity, and structural molecule activity (Fig. 5B). COG classification showed that most proteins were involved in “posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones”, “translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis”, energy production and conversion, and cytoskeleton (Table 2).

Proteins related to the adaptation response of B. odoriphaga to benzothiazole

Proteins that were significantly affected by the benzothiazole treatment at 24 h but not at 6 h were considered to be related to the adaptation response of B. odoriphaga to benzothiazole. A total of 67 significantly affected proteins (43 up-regulated and 24 down-regulated) were identified (Table 3). These proteins were assigned to GO categories. The main enrichment categories were cellular and metabolic processes, cell and cell part, organelle, binding, and catalytic activity (Fig. 5C). The COG analysis categorized these 67 proteins into 16 functional groups, and the most frequently detected functional categories were amino acid transport and metabolism, carbohydrate transport and metabolism, energy production and conversion, “posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones”, “translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis”, general function prediction and signal transduction mechanisms (Table 3).

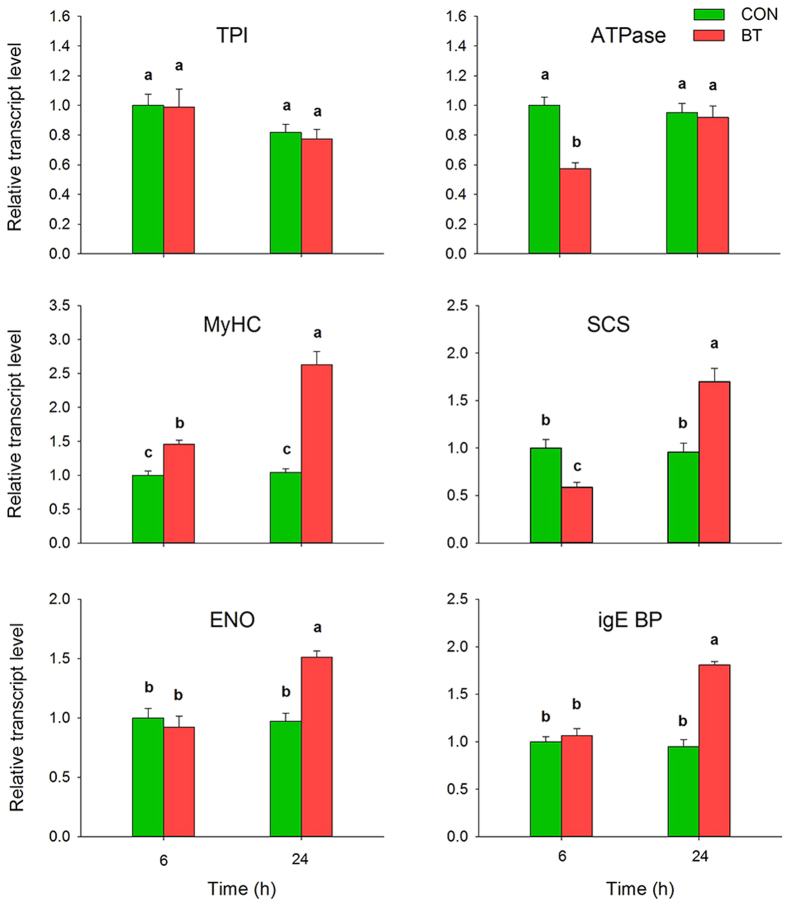

qRT-PCR analysis of differentially expressed proteins

To determine whether gene expression is correlated between mRNA and protein levels, the following six proteins that are mainly involved in the categories of action mechanism, stress mechanism and adaption mechanism were selected for qRT-PCR analysis: triose-phosphate isomerase (TPI), vacuolar ATP synthase subunit H (V-ATPase), myosin heavy chain (MyHC), succinyl-CoA synthetase alpha (SCS), putative enolase (ENO) and putative IgE binding protein (epsilon BP). The expression levels of all selected genes encoding these proteins, with the exception of TPI, matched well with the iTRAQ results (Fig. 6). According to the qRT-PCR results, these genes had similar mRNA and protein expression patterns with similar or slightly different overall quantitative proteomics results.

Figure 6. mRNA expression level analysis (qRT-PCR) of 6 proteins of B. odoriphaga after 6 and 24 h of benzothiazole treatment.

The relative expression level was normalized to an internal standard, ribosomal protein S3 (RPS3). Bars represent mean ± SE (n = 6). Different lower-case letters above the bars indicate significant differences at P < 0.05. TPI: triose-phosphate isomerase; V-ATPase: vacuolar ATP synthase subunit H; MyHC: myosin heavy chain; SCS: succinyl-CoA synthetase; ENO: enolase; epsilon BP: IgE binding protein.

Discussion

In this study, an iTRAQ-based proteomics approach was used to quantitatively describe changes in the protein profile of B. odoriphaga that occur in response to the microbial secondary metabolite benzothiazole. The iTRAQ-coupled LC-MS/MS analysis identified 863 proteins, of which 92 showed altered expression. Motility observations showed that B. odoriphaga larvae were poisoned after 6 h of benzothiazole and recovered after treatment for 24 h. To understand how protein expression responded to benzothiazole, the differentially expressed proteins were divided into three categories: those related to the action mechanism, to the stress mechanism and to the adaption mechanism.

Among the 14 proteins that exhibited altered expression upon benzothiazole treatment, most were involved in energy production and carbohydrate and nucleotide metabolism, including triose-phosphate isomerase (TPI), vacuolar ATP synthase subunit H (V-ATPase), putative peroxisomal 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase (KAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD), and nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDPK).

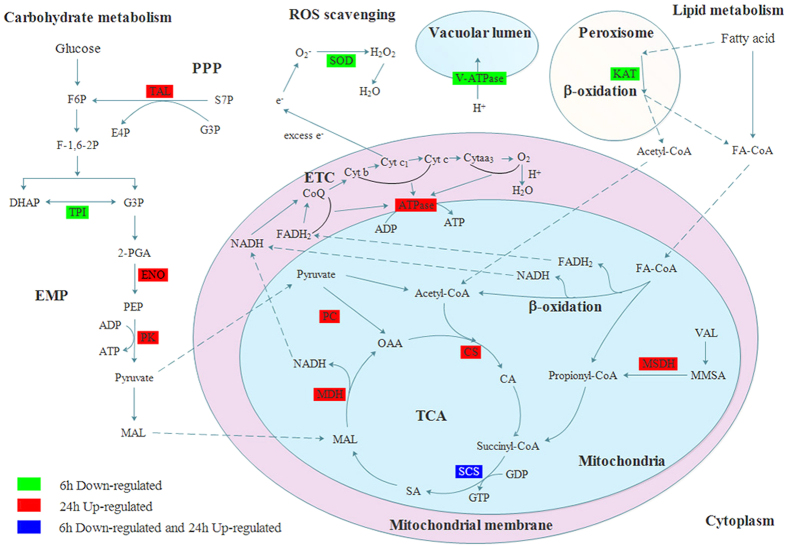

Triose-phosphate isomerase (TPI) is a key enzyme of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis and plays a vital role in the development and metabolism of organisms28. TPI catalyzes the interconversion of dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (G3P) (Fig. 7). G3P can be further processed to pyruvate, permitting the generation of NADH and ATP. Thus, TPI enables these three-carbon compounds to be processed via glycolytic metabolism. No ATP would be produced in the glycolytic pathway without this reaction29. The reduced level of TPI detected here indicates that benzothiazole inhibits energy production by affecting glycolytic processes.

Figure 7. A summary of some of the biological pathways affected by benzothiazole in B. odoriphaga.

Green boxes represent proteins that were only down-regulated at 6 h after benzothiazole treatment, red boxes represent proteins that were only up-regulated at 24 h after benzothiazole treatment, and blue boxes indicate proteins that were down-regulated at 6 h and up-regulated at 24 h after benzothiazole treatment. EMP: glycolytic pathway; PPP: pentose phosphate pathway; TCA: tricarboxylic acid cycle; ETC: electron transfer chain; F6P: fructose 6-phosphate; F-1,6-2 P: fructose-1,6-diphosphate; TAL: putative transaldolase; S7P: sedoheptulose-7-phosphate; G3P: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; E4P: erythrose-4-phosphate; TPI: triose-phosphate isomerase; DHAP: dihydroxyacetone phosphate; 2-PGA: 2-phosphoglycerate; ENO: putative enolase; PEP: phosphoenolpyruvate; PK: pyruvate kinase; MAL: malate; PC: pyruvate carboxylase; OAA: oxaloacetic acid; CS: citrate synthase 1; CA: citric acid; SCS: succinyl-CoA synthetase alpha; SA: succinic acid; MDH: malate dehydrogenase; VAL: valine; MMSA: methylmalonate semialdehyde; MSDH: methylmalonate semialdehyde dehydrogenase; FA-CoA: acyl-coenzyme A; KAT: peroxisomal 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase; ATPase: ATP synthase beta subunit; V-ATPase: vacuolar ATP synthase subunit H; SOD: superoxide dismutase.

In addition, vacuolar ATP synthase subunit H (V-ATPase) is a universal and vital component of eukaryotic organisms because it is the major proton pump of vacuolar membranes (Fig. 7). V-ATPase is a multi-subunit enzyme that comprises a membrane sector and a cytosolic catalytic sector and plays a major role in providing energy for several secondary uptake cellular processes30. The decreased expression of vacuolar ATP synthase subunit H suggests that benzothiazole inhibits the energy production and cellular uptake processes of B. odoriphaga. This provides further evidence that benzothiazole treatment can inhibit the energy production of B. odoriphaga. This is consistent with our observations that the larvae were barely able to crawl or ingest at 6 h after benzothiazole treatment (Fig. 2E).

The putative enzyme peroxisomal 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase (KAT) catalyzes the final step of fatty acid β-oxidation in the peroxisome (Fig. 7), which involves the thiolytic cleavage of 3-ketoacyl-CoA to acetyl-CoA (C2) and acyl-CoA (Cn−2)31,32. Acetyl-CoA is a central molecule derived from glucose, fatty acid, and amino acid catabolism and is involved in many metabolic pathways and transformations33. In addition, acetyl-CoA is preferentially directed into the mitochondria for the synthesis of ketone bodies and ATP34. Down-regulation of peroxisomal 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase inhibits the generation of acetyl-CoA and decreases the synthesis of ATP. The down-regulation of this set of proteins suggests that the mechanism of action of benzothiazole is related to the inhibition of energy production in B. odoriphaga.

Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) is the initial and rate-limiting enzyme in the pyrimidine catabolic pathway, in which thymine and uracil are converted into β-alanine or β-aminoisobutyrate using the cofactors NADH or NADPH35,36. β-alanine is involved in many metabolic pathways and neurotransmitter functions37. DPD down-regulation leads to the disruption of normal pyrimidine metabolism. Additionally, DPD is a crucial enzyme for the growth and survival of the parasite under a glucose-limited environment36. Our previous study showed that the carbohydrate content of B. odoriphaga declines after benzothiazole treatment for 6 h14. In this case, DPD may play a key role in larval survival. However, the present study found that the expression of DPD was down-regulated, which suggested that the survival of B. odoriphaga was inhibited by benzothiazole through its effect on DPD expression.

Nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDPK) is a ubiquitous enzyme that catalyzes the final phosphorylation of nucleoside diphosphates. This reaction uses NTP as a phosphate donor to provide sufficient nucleosides for DNA and RNA replication38,39. Moreover, NDPK is involved in several signal transduction pathways and has been described as a housekeeping enzyme that maintains a balanced pool of intracellular nucleotides40. The reduced level of NDPK suggested that benzothiazole disturbed the balance of nucleotide metabolic processes and interfered with the synthesis of DNA and RNA in B. odoriphaga.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is widely distributed in living organisms and catalyzes the conversion of superoxide radicals to molecular oxygen and hydrogen peroxide41,42. Thus, SOD is a critical enzyme for protecting the cell against oxygen damage (Fig. 7). The observed decrease in SOD expression implies that benzothiazole treatment might influence superoxide radical scavenging and interfere with the protection mechanism in B. odoriphaga. Moreover, the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes play key roles in the metabolism of pharmaceutical drugs and the detoxification of xenobiotics43. In the present study, CYP expression was found to be decreased in the benzothiazole treatment group (Table 2), which suggested that the detoxification process is inhibited by benzothiazole. Additionally, our previous study showed that benzothiazole decreases the activity of glutathione S-transferase (GST)14, which also plays a critical role in detoxification pathways. Hence, the inhibition of the defense mechanism may be related to the mode of action of benzothiazole.

Cytoskeletal proteins are involved in many vital metabolic processes, such as cellular polarity, cell elongation, division, endocytosis and vesicular trafficking44,45. In our present study, the expression of two cytoskeleton-related proteins, actin-2 and calponin/transgelin, were up-regulated after exposure to benzothiazole. These results are in agreement with a number of previous studies, which demonstrated that spirotetramat, sarin, hydrogen peroxide and ethanol treatment increases actin synthesis46,47,48. These results indicate that actin plays an important role in the response to external stimuli and participates in innate immunity49. The increased expression of cytoskeleton components can reinforce the cell’s physical barrier to prevent further exposure to the stimuli and consequent injury.

The expression of 11 proteins was altered by benzothiazole treatment at both 6 and 24 h. These proteins were related to the stress response, and their possible functions are described below:

Succinyl-CoA synthetase alpha (SCS) plays a key role in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) and ketone metabolism, and SCS is the only mitochondrial enzyme that is capable of generating ATP via substrate-level phosphorylation in the absence of oxygen50. In the present study, the expression of SCS decreased at 6 h and increased at 24 h after exposure to benzothiazole. The metabolism of the larvae was inhibited by benzothiazole at 6 h, and after autoimmunity, the metabolic process was recovered and adapted to benzothiazole at 24 h. This finding is consistent with our motility observations (Fig. 2E and F), which indicated that the energy production of B. odoriphaga was decreased at 6 h and recovered at 24 h after exposure to benzothiazole.

Putative S3aE ribosomal protein (RPS3aE) is involved in many cellular processes, such as cell growth, protein synthesis and apoptosis51. In addition, some studies have suggested that RPS3a can alleviate copper stress in Argopecten purpuratus52. Soybean RPS3a has been associated with disease resistance and flooding tolerance53. A recent study suggests that RPS3aE might improve salt tolerance in three heterologous organisms54. In the present study, RPS3aE was up-regulated both at 6 and 24 h. Thus, RPS3aE is a multifunctional protein that plays extra-ribosomal roles in the stress response to benzothiazole.

Additionally, there were increases in proteins related to the stress response to benzothiazole. These up-regulated proteins included myosin heavy chain (MyHC), the functional myosin motor molecule, which demonstrates isoform plasticity in response to disease states55; putative polyadenylate-binding protein rrm superfamily (PABP), an enzyme involved in mRNA metabolism, which plays a key role in the stabilization of mRNA and promotes the initiation of translation56; calcium-transporting ATPase sarcoplasmic reticulum type, a membrane protein that performs the vital role of transporting Ca2+ up to the limiting electrochemical gradient from the cytoplasm into the sarcoplasmic reticulum57; putative elongation factor 1-beta2, a major translational factor and an important multifunctional protein58; and profilin, an actin monomer-sequestering protein that regulates actin dynamics at plasma membranes59. This range of changes suggested that B. odoriphaga mobilized the stress response mechanism to withstand ambient pressure and help it to adapt to benzothiazole.

The analysis focused on 67 proteins that exhibited different patterns of expression in response to benzothiazole only at 24 h. Many of these proteins were involved in metabolic processes, including carbohydrate metabolism, energy metabolism, amino acid metabolism, lipid metabolism and inorganic ion metabolism.

Among the proteins related to carbohydrate metabolism, many were involved in glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP). Putative enolase (ENO) is a key enzyme that catalyzes the ATP-generated conversion of 2-phospho-D-glycerate (2-PGA) to phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) in the glycolytic pathway60. Putative transaldolase (TAL) is a nearly ubiquitous enzyme involved in the PPP, which catalyzes the transfer of a three-carbon unit (dihydroxyacetone) from donor compounds to aldehyde acceptor compounds. Furthermore, TAL also plays a crucial role in the central metabolic pathway that provides redox cofactors such as NADPH and building blocks for the biosynthesis of nucleotides and nucleic acids61. Pyruvate kinase (PK) is a rate-limiting enzyme that catalyzes the final step of glycolysis, which converts phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and ADP to ATP and pyruvate, and plays a key role in controlling glycolytic flux62. These proteins were up-regulated, suggesting that the surviving larvae enhanced their carbohydrate metabolism to promote the adaptation response to benzothiazole.

In total, 7 proteins involved in energy metabolism had changed levels of expression. All of these proteins underwent increased expression, including the putative IgE binding protein (epsilon BP), a galactoside-specific lectin containing a carbohydrate recognition domain63. Probable citrate synthase 1 (CS) is localized in the mitochondrial matrix and catalyzes the condensation of acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate to form citrate and CoA, the first step of the Krebs cycle64. ATP synthase beta subunit (ATPase) catalyzes the rate-limiting step of ATP production in eukaryotic cells65. Malate dehydrogenase 1 (MDH) is an enzyme in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) that catalyzes the interconversion of malate (MAL) and oxaloacetic acid (OAA) using the coenzyme NAD+/NADH66. Moreover, MDH is responsible for the exchange of reducing equivalents between metabolic processes in distinct cell compartments67. Pyruvate carboxylase (PC) is a multifunctional, biotin-containing enzyme that catalyzes the MgATP- and bicarbonate-dependent carboxylation of pyruvate to form oxaloacetate (OAA). OAA is the key intermediate in the TCA pathway; therefore, this reaction is an important anaplerotic process in central metabolism68,69. Putative methylmalonate semialdehyde dehydrogenase (MSDH) is a mitochondrial enzyme that catalyzes the NAD-dependent oxidation of methylmalonate semialdehyde (MMSA) to propionyl-CoA through acylation and deacylation steps70. ATP synthase subunit beta vacuolar is a proton-translocating enzyme that plays a key role in providing energy for many secondary uptake cellular processes30. The up-regulation of such a wide range of energy metabolism-related proteins indicates that benzothiazole inhibits energy production in B. odoriphaga. Thus, more energy must be synthesized to adapt to treatment with this compound.

Many other proteins with altered expression were also identified, including those involved in amino acid metabolism, lipid metabolism and inorganic ion metabolism. These included pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase (P5CS), a rate-limiting enzyme in proline biosynthesis, which catalyzes the coupled phosphorylation and reduction-conversion of glutamate to pyrroline-5-carboxylate (P5C)71. Arginine kinase (AK) is an important enzyme for maintaining energy balance and is associated with ATP regeneration, energy transport and muscle contraction in invertebrates72. Serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT) catalyzes the interconversion of L-serine and glycine with the transfer of one-carbon units to and from tetrahydrofolate73. Putative 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate synthetase (PAPSS) catalyzes the synthesis of 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) from ATP and inorganic sulfate74. Na+/K+ ATPase alpha subunit is an energy-transducing ion pump75. Putative microtubule-associated complex regulates the dynamic structure of microtubules76. The enzyme 3-oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] reductase (OAR) is involved in the reductive step of fatty acid biosynthesis using NADPH as a cofactor77. These proteins are up-regulated, suggesting that many amino acids, lipids and inorganic ion-related enzymes enhance larval metabolism to defend against and adapt to benzothiazole treatment.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our data revealed a comprehensive global protein response of B. odoriphaga upon treatment with benzothiazole. A detailed analysis of the proteins with altered expression suggested that the response of B. odoriphaga varies with exposure time. These proteins are divided into categories related to the action mechanism, stress mechanism and adaption mechanism. The reduction in energy metabolism, inhibition of detoxification processes and interference with DNA and RNA synthesis were potentially associated with the mode of action of benzothiazole. In addition, myosin heavy chain (MyHC), succinyl-CoA synthetase (SCS), polyA-binding protein and Ca+-transporting ATPase may be involved in the stress response to benzothiazole. The up-regulated expression of proteins related to carbohydrate metabolism, energy production and conversion pathways, amino acid metabolism, lipid metabolism and inorganic ion metabolism were responsible for the adaption to benzothiazole. Further studies are needed to identify the direct binding target of benzothiazole and to clearly elucidate the action mechanism of this microbial secondary metabolite.

Materials and Methods

Insect culture and benzothiazole treatment

A laboratory colony of B. odoriphaga was collected from a Chinese chive greenhouse in Liaocheng, Shandong Province, China (36°02′N, 115°30′E) in 2013. The insects were reared on fresh chive rhizomes (1 cm in length) and placed in Petri dishes, which were maintained at 25 ± 1 °C under 70 ± 5% RH and a photoperiod of 14:10 h (L:D).

Newly emerged fourth-instar larvae of B. odoriphaga were fumigated with the LC30 of benzothiazole (this was determined in our previous investigation to be 0.4729 μL/L14). After 6 and 24 h of continuous fumigation at 25 °C, the motility and ingestion of B. odoriphaga were observed and recorded for the control and benzothiazole treatment groups. In addition, surviving larvae in the benzothiazole and control treatments were collected, washed with double distilled water and stored at −80 °C. Five replications were used per benzothiazole and control treatment, and the biological replicates were performed three times.

Protein extraction

Total proteins from each sample (n = 50 larvae/treatment, mixed from 5 replications) were pulverized thoroughly in liquid nitrogen and extracted with lysis buffer (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 40 mM Tris-HCl, 4% CHAPS, 1 mM PMSF, 2 mM EDTA, and 10 mM DTT; pH 8.5). The suspension was sonicated at 200 W for 15 min and then centrifuged at 30,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube, 10 mM DTT was then added, and the tube was incubated at 56 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, 55 mM iodoacetamide (IAM) was added, and the tube was incubated for 45 min in the dark. The protein was precipitated with chilled acetone for 2 h at −20 °C. After centrifugation at 30,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C, the precipitated protein was suspended in 0.5 M tetraethylammonium bromide (TEAB) buffer. The protein concentration was determined using the Bradford dye-binding assay78, and 100 μg of protein was taken from each sample and digested with trypsin overnight at 37 °C before being dried under vacuum.

iTRAQ labeling and strong cation exchange (SCX) fractionation

After trypsin digestion and desiccation, the peptides were labeled with 8-plex iTRAQ reagent (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The samples obtained from larvae challenged with distilled water for 6 h were labeled iTRAQ-113 and −115 (CON-6h1 and CON-6h2, two biological replicates). The samples obtained from larvae challenged with benzothiazole for 6 h were labeled iTRAQ-114 and −116 (BT-6h1 and BT-6h2). The samples obtained from larvae challenged with distilled water for 24 h were labeled iTRAQ-117 and −119 (CON-24h1 and CON-24h2). The samples obtained from larvae challenged with benzothiazole for 24 h were labeled iTRAQ-118 and −121 (BT-24h1 and BT-24h2). The peptides labeled with isobaric tags were incubated for 2 h at room temperature and then pooled and dried by vacuum centrifugation.

The dried peptide mixtures were dissolved in 4 mL of buffer A (25 mM NaH2PO4 in 25% ACN, pH 2.7). After centrifugation, the supernatant was loaded onto a 4.6 × 250 mm Ultremex SCX column containing 5-μm particles (Phenomenex). Elution was performed using a linear binary gradient at a flow rate of 1 mL/min with a gradient of buffer A for 10 min, 5–60% buffer B (25 mM NaH2PO4, 1 M KCl in 25% ACN, pH 2.7) for 27 min, and 60–100% buffer B for 1 min. The system was then maintained at 100% buffer B for 1 min before equilibrating with buffer A for 10 min prior to the next injection. Elution was monitored by measuring the UV absorbance at 214 nm, and fractions were collected at 1 min intervals. The eluted peptides were pooled into 20 fractions, desalted with a Strata X C18 column (Phenomenex) and dried under vacuum.

LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis based on Triple TOF 5600

All fractions were resuspended in buffer A [0.1% formic acid (FA), 5% CAN] and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min. The average final peptide concentration was approximately 0.5 μg/μL. Then, 10 μL of supernatant was loaded onto a 2-cm C18 trap column attached to an LC-20AD nanoHPLC (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) using the autosampler, and the peptides were eluted onto an analytical C18 column (inner diameter of 75 μm) that was packed in-house. The samples were loaded at 8 μL/min for 4 min, after which a 35 min gradient was run at 300 nL/min starting from 2–35% buffer B (95% ACN, 0.1% FA), followed by a 5 min linear gradient to 60%, then by a 2 min linear gradient to 80%, and maintenance in 80% buffer B for 4 min, followed by a final return to 5% buffer B in 1 min. Data acquisition was performed using a TripleTOF 5600 system (AB SCIEX, Concord, ON, Canada) fitted with a Nanospray III source (AB SCIEX) and a pulled quartz tip as the emitter (New Objectives, Woburn, MA, USA). Data were acquired using an ion-spray voltage of 2.5 kV, a curtain gas of 30 psi, a nebulizer gas of 15 psi, and an interface heater temperature of 150 °C.

Proteomic data analysis

The raw MS/MS data were converted to mgf files and merged into a dataset using Proteome Discoverer 1.2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Protein identification was performed using the Mascot search engine (Matrix Science, London, UK; version 2.3.02) against the NCBI Nematocera database (125804 sequences). For protein identification, a mass tolerance of 0.05 Da was permitted for intact peptide masses and 0.1 Da was permitted for fragmented ions, with allowance for one missed cleavage in the trypsin digests. Settings included Gln → pyro-Glu (N-term Q), Oxidation (M), and iTRAQ8plex (Y) as the potential variable modifications, and Carbamidomethyl (C), iTRAQ8plex (N-term), and iTRAQ8plex (K) were used as the fixed modifications. The charge states of the peptides were set to +2 and +3, and the monoisotopic mass was used. To reduce the probability of false peptide identification, only peptides at the 95% confidence interval (assessed by a Mascot probability analysis as greater than “identity”) were counted as identified. In addition, each confident protein identification involved at least one unique peptide. For protein quantitation, it was required that a protein be represented by at least two unique spectra. The quantitative protein ratios were weighted and normalized to the median ratio in Mascot. A protein was considered statistically significant only if there was a fold change of >1.20 or <0.83 in at least one biological replicate (p < 0.05) and if the expression trend was consistent in the rest of the biological replicates.

The identified proteins were categorized according to their Gene Ontology (GO) annotation (http://www.geneontology.org/). The Cluster of Orthologous Groups of proteins (COG) analysis was also conducted (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG/). The metabolic pathway analysis of the proteins was conducted according to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway Database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg).

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the frozen samples of benzothiazole-treated and control larvae using the TransZol Up Kit (Transgen, Beijing, China). For each sample, approximately 1.0 μg of total RNA was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis using the TransScript All-in-One First-Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix for qPCR Kit (Transgen). Gene-specific primers were designed using Primer Software Version 5.0 (Premier Biosoft International, CA, USA). The sequences of the F and R primers used are shown in Table S1. qRT-PCR was performed using a Bio-Rad CFX Connect Real-Time System (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) in a total volume of 20 μL volume with 1.0 μL of cDNA, 1.0 μL of each primer, 10 μL of Tip Green qPCR SuperMix (Transgen) and 7.0 μL of double distilled water. The cycling conditions were 30 s at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of amplification (95 °C for 5 s, 58 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 10 s). Three technical replicates and two biological replicates were conducted for all experiments. For the normalization of gene expression, ribosomal protein S3 (RPS3) gene was used as an internal standard, and the formula 2−∆∆Ct was used to determine the relative expression. The data were statistically analyzed using the Student-Newman-Keuls test (SPSS v. 13.0 for Windows) (P < 0.05).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Zhao, Y. et al. Proteomic profile of the Bradysia odoriphaga in response to the microbial secondary metabolite benzothiazole. Sci. Rep. 6, 37730; doi: 10.1038/srep37730 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest from the Ministry of Agriculture of China (201303027) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31572040 and 31501651). We would like to thank Dr. Fengshan Yang (Heilongjiang University, Harbin, China) for his guidance and assistance in data analysis.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Y.Z., F.L. and W.M. designed the research. Y.Z., K.C. and Y.W. performed the experiments. Y.Z., C.X. and Q.W. analyzed the data. Y.Z., Z.Z. and W.M. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Zhang H., Mallik A. & Zeng R. S. Control of Panama disease of banana by rotating and intercropping with Chinese chive (Allium tuberosum Rottler): role of plant volatiles. Journal of chemical ecology 39, 243–252 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imahori Y. et al. Physiological and quality responses of Chinese chive leaves to low oxygen atmosphere. Postharvest Biology and Technology 31, 295–303 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Chen S., Moens M., Han R. & Clercq P. Efficacy of entomopathogenic nematodes (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae) against the chive gnat, Bradysia odoriphaga. Journal of Pest Science 86, 551–561 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Li W. et al. Effects of Temperature on the Age-Stage, Two-Sex Life Table of Bradysia odoriphaga (Diptera: Sciaridae). J Econ Entomol 108, 126–134 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P. et al. Life table study of the effects of sublethal concentrations of thiamethoxam on Bradysia odoriphaga Yang and Zhang. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology 111, 31–37 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P. et al. Dissipation dynamics of clothianidin and its efficacy to control Bradysia odoriphaga Yang and Zhang in Chinese chive ecosystems. Pest Manag Sci (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert R. M. & A. D. K. Jr. Identification of some volatile constituents of Aspergillus clavatus. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 30, 786–790 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Gallois A., Gross B., Langlois D., Spinnler H.-E. & Brunerie P. Influence of culture conditions on production of flavour compounds by 29 ligninolytic Basidiomycetes. Mycological Research 94, 494–504 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Fernando W. G. D., Ramarathnam R., Krishnamoorthy A. S. & Savchuk S. C. Identification and use of potential bacterial organic antifungal volatiles in biocontrol. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 37, 955–964 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. W., Ji J., Wang C., Mu W. & Liu F. Evaluation and identification of the potential nematicidal volatiles produced by bacillus subtilis. Acta Phytopathologica sinica 39, 304–309 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Yang X., Li X., Mu W. & Liu F. Antifungal, Insecticidal and Herbicidal Properties of Volatile Components from Paenibacillus polymyxa Strain BMP-11. Agricultural Sciences in China 10, 728–736 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. et al. Biological activity of benzothiazole against Bradysia odoriphaga (Diptera: Sciaridae) at different developmental stages. Acta Entomologica Sinica 57, 45–51 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. et al. Sublethal concentration of benzothiazole adversely affect development, reproduction and longevity of Bradysia odoriphaga (Diptera: Sciaridae). Phytoparasitica 44, 115–124 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. et al. Effects of the microbial secondary metabolite benzothiazole on the nutritional physiology and enzyme activities of Bradysia odoriphaga (Diptera: Sciaridae). Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology 129, 49–55 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q. S. et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis reveals that antioxidation mechanisms contribute to cold tolerance in plantain (Musa paradisiaca L.; ABB Group) seedlings. Molecular & cellular proteomics: MCP 11, 1853–1869 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos M. F., Soares A. M., Correia A. C. & Esteves A. C. Proteins in ecotoxicology - how, why and why not? Proteomics 10, 873–887 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei X. et al. Proteomic analysis of zoxamide-induced changes in Phytophthora cactorum. Pestic Biochem Physiol 113, 31–39 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. et al. Quantitative Proteomics Reveals Membrane Protein-Mediated Hypersaline Sensitivity and Adaptation in Halophilic Nocardiopsis xinjiangensis. Journal of proteome research 15, 68–85 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Qin F., Liu W. & Wang X. Differential proteomics profiling of the ova between healthy and Rice stripe virus-infected female insects of Laodelphax striatellus. Scientific reports 6, 27216 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau J.-M. et al. Drug induced proteome changes in Candida albicans: Comparison of the effect of β(1,3) glucan synthase inhibitors and two triazoles, fluconazole and itraconazole. Proreomics 3, 325–336 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bantscheff M. et al. Quantitative chemical proteomics reveals mechanisms of action of clinical ABL kinase inhibitors. Nature biotechnology 25, 1035–1044 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M. A., Silva J. C., Geromanos S. J. & Townsend C. A. Quantitative proteomic analysis of drug-induced changes in mycobacteria. Journal of proteome research 5, 54–63 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao J. et al. iTRAQ-Based Quantitative Proteomic Analysis of the Antimicrobial Mechanism of Peptide F1 against Escherichia coli. J Agric Food Chem 63, 7190–7197 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang Z. et al. Proteomic profile of the plant-pathogenic oomycete Phytophthora capsici in response to the fungicide pyrimorph. Proteomics 15, 2972–2982 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan H., Xu Y., Du C. & Wu X. Phloem sap proteome studied by iTRAQ provides integrated insight into salinity response mechanisms in cucumber plants. Journal of proteomics 125, 54–67 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. et al. Jinggangmycin increases fecundity of the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens (Stal) via fatty acid synthase gene expression. Journal of proteomics 130, 140–149 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X. J. et al. iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomic analysis reveals potential factors associated with the enhancement of phenazine-1-carboxamide production in Pseudomonas chlororaphis P3. Scientific reports 6, 27393 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles J. R. Enzyme Catalysis - Not Different, Just Better. Nature 350, 121–124 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J. et al. Molecular identification, immunolocalization, and characterization of Clonorchis sinensis triosephosphate isomerase. Parasitology research 114, 3117–3124 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcel B. M., Aslund L., Pettersson U. & Andersson B. Trypanosoma cruzi: a putative vacuolar ATP synthase subunit and a CAAX prenyl protease-encoding gene, as examples of gene identification in genome projects. Experimental parasitology 95, 176–186 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham I. A. Seed storage oil mobilization. Annual review of plant biology 59, 115–142 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidaleo M. et al. A role for the peroxisomal 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase B enzyme in the control of PPARalpha-mediated upregulation of SREBP-2 target genes in the liver. Biochimie 93, 876–891 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivoruchko A., Zhang Y., Siewers V., Chen Y. & Nielsen J. Microbial acetyl-CoA metabolism and metabolic engineering. Metabolic engineering 28, 28–42 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L. & Tu B. P. Acetyl-CoA and the regulation of metabolism: mechanisms and consequences. Current opinion in cell biology 33, 125–131 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z. H., Zhang R. & Diasio R. B. Purification and Characterization of Dihydropyrimidine Dehydrogenase from Human Liver. Journal of biological chemistry 267, 17102–17109 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumel-Alterzon S., Weber C., Guillen N. & Ankri S. Identification of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase as a virulence factor essential for the survival of Entamoeba histolytica in glucose-poor environments. Cellular microbiology 15, 130–144 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macphee S., Weaver I. N. & Weaver D. F. An Evaluation of Interindividual Responses to the Orally Administered Neurotransmitter beta-Alanine. Journal of amino acids 2013, 429847 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonin P. et al. Catalytic mechanism of nucleoside diphosphate kinase investigated using nucleotide analogues, viscosity effects, and X-ray crystallography. Biochemistry 38, 7265–7272 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwood P. V. & Wieland T. Nucleoside diphosphate kinase as protein histidine kinase. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s archives of pharmacology 388, 153–160 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard M. A., Ray N. B., Olcott M. C., Hendricks S. P. & Mathews C. K. Metabolic Functions of Microbial Nucleoside Diphosphate Kinases. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes 32, 259–267 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. J., Shin D. S., Getzoff E. D. & Tainer J. A. The structural biochemistry of the superoxide dismutases. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1804, 245–262 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng Y. et al. Superoxide dismutases and superoxide reductases. Chemical reviews 114, 3854–3918 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuarters A. B., Wolf M. W., Hunt A. P. & Lehnert N. 1958-2014: after 56 years of research, cytochrome p450 reactivity is finally explained. Angewandte Chemie 53, 4750–4752 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra M., Huang J. & Balasubramanian M. K. The yeast actin cytoskeleton. FEMS microbiology reviews 38, 213–227 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. et al. Comprehensive maternal serum proteomics identifies the cytoskeletal proteins as non-invasive biomarkers in prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart defects. Scientific reports 6, 19248 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courgeon A. M. et al. Effect of hydrogen peroxide on cytoskeletal proteins of Drosophila cells: comparison with heat shock and other stresses. Experimental cell research 204, 30–37 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damodaran T. V., Mecklai A. A. & Abou-Donia M. B. Sarin Causes Altered Time Course of mRNA Expression of Alpha Tubulin in the Central Nervous System of Rats. Neurochemical Research 27, 177–181 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi J. et al. Proteomics-based identification and analysis proteins associated with spirotetramat tolerance in Aphis gossypii Glover. Pestic Biochem Physiol 119, 74–80 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vierstraete E. et al. A proteomic approach for the analysis of instantly released wound and immune proteins in Drosophila melanogaster hemolymph. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101, 470–475 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips D., Aponte A. M., French S. A., Chess D. J. & Balaban R. S. Succinyl-CoA synthetase is a phosphate target for the activation of mitochondrial metabolism. Biochemistry 48, 7140–7149 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim K. H. et al. RPS3a over-expressed in HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma enhances the HBx-induced NF-kappaB signaling via its novel chaperoning function. PloS one 6, e22258 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapata M., Tanguy A., David E., Moraga D. & Riquelme C. Transcriptomic response of Argopecten purpuratus post-larvae to copper exposure under experimental conditions. Gene 442, 37–46 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen V. T. et al. Mapping of Quantitative Trait Loci Associated with Resistance to and Flooding Tolerance in Soybean. Crop Science 52, 2481 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Liang X. et al. A ribosomal protein AgRPS3aE from halophilic Aspergillus glaucus confers salt tolerance in heterologous organisms. International journal of molecular sciences 16, 3058–3070 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korte F. S., Herron T. J., Rovetto M. J. & McDonald K. S. Power output is linearly related to MyHC content in rat skinned myocytes and isolated working hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289, 801–812 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollig F. et al. Affinity purification of ARE-binding proteins identifies poly(A)-binding protein 1 as a potential substrate in MK2-induced mRNA stabilization. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 301, 665–670 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen T. L., Olesen C., Jensen A. M., Moller J. V. & Nissen P. Crystals of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-ATPase. Journal of biotechnology 124, 704–716 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejiri S. Moonlighting functions of polypeptide elongation factor 1: from actin bundling to zinc finger protein R1-associated nuclear localization. Bioscience, biotechnology, and biochemistry 66, 1–21 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jockusch B. M., Murk K. & Rothkegel M. The profile of Profilins. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 159, 131–149 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y. et al. Alpha-enolase as a potential cancer prognostic marker promotes cell growth, migration, and invasion in glioma. Molecular Cancer 13, 1–24 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samland A. K. & Sprenger G. A. Transaldolase: from biochemistry to human disease. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 41, 1482–1494 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P., Li Z., Fu R., Wu H. & Li Z. Pyruvate kinase M2 facilitates colon cancer cell migration via the modulation of STAT3 signalling. Cellular signalling 26, 1853–1862 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigeri L. G. & Liu F. T. Surface expression of functional IgE binding protein, an endogenous lectin, on mast cells and macrophages lectin, on mast cells and macrophages. Journal of immunology 148, 861–867 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas T. P. et al. Evaluation of citrate synthase activity in brain of rats submitted to an animal model of mania induced by ouabain. Molecular and cellular biochemistry 341, 245–249 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo J. M. Control of the ATP synthase beta subunit expression by RNA-binding proteins TIA-1, TIAR, and HuR. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 348, 703–711 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menckhoff L., Mielke-Ehret N., Buck F., Vuletic M. & Luthje S. Plasma membrane-associated malate dehydrogenase of maize (Zea mays L.) roots: native versus recombinant protein. Journal of proteomics 80, 66–77 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E. Y. et al. Acetylation of malate dehydrogenase 1 promotes adipogenic differentiation via activating its enzymatic activity. Journal of lipid research 53, 1864–1876 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lietzan A. D. & St Maurice M. Insights into the carboxyltransferase reaction of pyruvate carboxylase from the structures of bound product and intermediate analogs. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 441, 377–382 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jitrapakdee S. et al. Structure, mechanism and regulation of pyruvate carboxylase. The Biochemical journal 413, 369–387 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talfournier F., Stines-Chaumeil C. & Branlant G. Methylmalonate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase from Bacillus subtilis: substrate specificity and coenzyme A binding. The Journal of biological chemistry 286, 21971–21981 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L. et al. Isolation and characterization of a Delta1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase (NtP5CS) from Nitraria tangutorum Bobr. and functional comparison with its Arabidopsis homologue. Molecular biology reports 41, 563–572 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si Y. X. et al. Folding studies of arginine kinase from Euphausia superba using denaturants. Applied biochemistry and biotechnology 172, 3888–3901 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelaccio S. et al. Conformational transitions driven by pyridoxal-5′-phosphate uptake in the psychrophilic serine hydroxymethyltransferase from Psychromonas ingrahamii. Proteins 82, 2831–2841 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejima K. et al. Essential roles of 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate synthase in embryonic and larval development of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. The Journal of biological chemistry 281, 11431–11440 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z. & Askari A. Na+/K+-ATPase as a signal transducer. European Journal of Biochemistry 269, 2434–2439 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsvetkov P. O., Barbier P., Breuzard G., Peyrot V. & Devred F. Microtubule-associated proteins and tubulin interaction by isothermal titration calorimetry. Methods in cell biology 115, 283–302 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Ning F., Li X. & Teng M. Structural insights into cofactor recognition of yeast mitochondria 3-oxoacyl-ACP reductase OAR1. IUBMB life 65, 154–162 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72, 248–254 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.