Abstract

Background:

Designing the effective and early interventions can prevent progression of prediabetes to diabetes. Few studies have shown the effect of flaxseed on glycemic control. This study aimed to assess the effect of flaxseed powder on insulin resistance (IR) indices and blood pressure in prediabetic individuals.

Materials and Methods:

In a randomized clinical trial, 99 prediabetic individuals were randomly divided into three groups: two groups received 40 g (FG40) and 20 g (FG20) flaxseed powder daily for 12 weeks and the third group was the control (CG). Before and after the intervention, anthropometric measurements, blood pressure, fasting serum glucose (FSG), insulin, homeostasis model assessment IR index (HOMA-IR), beta-cell function, and insulin sensitivity were measured.

Results:

FSG significantly declined overall in all groups compared to the baseline (P = 0.002 in CG and FG20 groups and P = 0.001 in FG40). In contrast, mean of the changes in FSG was not significantly different between groups. Insulin concentration did not change significantly within and between the investigated groups. Although HOMA-IR reduced in FG20 (P = 0.033), the mean of changes was not significant between the three groups. Mean of beta-cell function increased in CG and FG40 groups compared to the baseline (P = 0.044 and P = 0.018, respectively), but mean of its changes did not show any difference between the three groups. The mean of changes in IR indices was not significant between the three groups. FG40 group had significantly lowered systolic blood pressure after the intervention (P = 0.005).

Conclusion:

Daily intake of flaxseed powder lowered blood pressure in prediabetes but did not improve glycemic and IR indices.

Keywords: Blood pressure, flaxseed, glucose, insulin resistance, prediabetes, randomized trial

INTRODUCTION

Prediabetes is a condition described by impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance[1] is characterized by elevated glycemic variables but not reaching diagnostic criteria of diabetes.[2] Although long-term complications associated with diabetes are well-known, researchers today have found that long-term damage, especially to the cardiovascular system, starts early in the prediabetes period.[3,4] Effective and early interventions including lifestyle modification and medication prevent or delay the onset of diabetes.[5]

The current studies indicate that 70% of prediabetic individuals develop diabetes.[6] It has been estimated that 79 million American people over the age of 20 years old suffer from prediabetes in 2010.[7] Tehran lipid and glucose study has reported that one-third of adult population in Tehran suffer from diabetes and glucose tolerance disorders.[8]

It has been reported that antioxidants reduce inflammation, insulin resistance (IR), and prevent diabetes progression.[9] Furthermore, studies have shown that diets rich in omega-3 fatty acids improve insulin sensitivity (IS) and glycemic control.[10] Flaxseed is a well-known seed due to its excellent source of lignan and n-3 fatty acid. Its lignan, secoisolariciresinol diglucoside, is an active ingredient, with antioxidant effect.[4,11] Flaxseed as a functional food[12] could increase fiber content, antioxidants, and omega-3 and, thus, be an effective intervention in prediabetes.[13] Dietary phytoestrogens (isoflavones and lignans) decrease risk of chronic diseases such as diabetes through influencing the regulation of inflammatory pathways.[14]

Few studies have demonstrated the positive role of flaxseed supplementation in improving inflammation, glycemic status, and oxidative stress among diabetic patients.[15] In a study on insulin resistant patients, flaxseed had a significantly positive impact on glycemic control and IS;[9] however, the sample size was not sufficient. Based on our findings, a limited number of conducted studies on people with prediabetes have reported contradictory results in terms of their consumption dosage.[16] The concentration on the development of secure and effective ways for preventing prediabetes progression to diabetes could reduce the costs imposed on the health sector. This clinical trial aimed to determine effect of flaxseed powder on IR indices and blood pressure in patients with prediabetes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and participants

This was a randomized controlled clinical trial and it was conducted in 2013 in Shiraz, Iran. Based on previous data,[9] to detect a change in mean homeostasis model assessment IR (HOMA-IR) of 1 standard deviation (SD) and to have a power of 80%, and 10% dropout rate, the calculated sample size was 33 in each group. In this trial, 99 prediabetic men and women were randomly selected from prediabetic patients screening project, all recruited via phone call, from Cardiovascular Research Center of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. Participants were considered eligible if they met the following criteria: (a) The body mass index (BMI) of 25–34.9 kg/m2, (b) fasting blood sugar of 100–125 mg/dl, (c) not use of insulin and other glucose lowering medications or herbal supplements, antioxidants, or omega-3 for at least 3 months before the study, and (d) willingness to participate. Exclusion criteria include (a) an inability or unwillingness to participate, (b) diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, (c) use of flaxseed, flaxseed oil, or omega-3, insulin or hypoglycemic medications, and dugs containing estrogen or progesterone, and (d) pregnancy or breastfeeding.

On the first visit, the study protocol and objectives were fully explained to all participants before they were given an informed written consent to sign. After a 2-week run in period, participants were randomly allocated to three groups who received 20 g flaxseed (FG20) and 40 g flaxseed (FG40) as intervention groups and a control group (CG) by random table. For 12 weeks, intervention groups took 40 g and 20 g flaxseed and the CG received no intervention until the end of the study. Flaxseed were milled and prepared by researchers, packed in 40 g and 20 g packets. All participants were scheduled to visit clinic every 2 weeks to obtain new flaxseed, and their adherence was evaluated. They received verbal and written training to keep the milled seed in the refrigerator and take it along with their meal in yogurt, milk, juice, or water. They were also asked to replace it with the same amount of carbohydrate and fat in their diet. While on the study, participants were instructed to maintain their habitual diets and levels of physical activity. They were tracked to follow the intervention protocol through phone call, once a week and in the face-to-face visits. Participants were asked to return any unused flaxseeds and adherence was assessed by counting them.

Measurements

General and demographic information questionnaires were filled out by the participants at the beginning of the study. Anthropometric parameters (height and weight) were measured at the accuracy of 0.1 kg by a BC-418MA device (Tanita Company, Tokyo, Japan). Height was measured by a tape at the accuracy of 0.1 cm in the standing posture by the wall without any shoes. BMI was calculated by dividing weight (kg) by square height (m2). Blood pressure was measured with a digital system (BC 08; Beurer, Ulm, Germany) whereas the participants were seated for >10 min. The average of duplicate measurements was considered for blood pressure. All measurements were done between 8 and 10 AM whereas the participants were fasting and not allowed to smoke.

After fasting for 12 h, blood samples were collected at the baseline and the end of intervention. Fasting venous blood samples were collected in 10 ml ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid-treated vacutainers for insulin and fasting glucose analysis. After centrifugation at 2600 ×g for 10 min, samples were liquated and stored at −80°C until batch analysis.

Concentration of fasting serum glucose (FSG) was tested by colorimetric enzymatic kit made by Pars Azmoon, Iran, and concentration of plasma insulin was calculated by Diametra kit of ELISA. IR was measured by HOMA-IR index and beta-cell function and IS were measured by HOMA calculator version 2.2.2 software, Oxford University, Oxford, United Kingdom.

Data analysis

SPSS 16 software (IBM Company, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data analysis. Data normalization was evaluated using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Data are expressed as means (±SD) change for each end point period. To compare means in the three groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used, and once a significant change was identified by ANOVA, Tukey test was performed to determine which groups differ. Furthermore, for comparing means in each group before and after the study, paired t-test was utilized. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all tests.

Ethical considerations

This protocol was approved by the Research Council and Ethic Committee, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, and registered in International Registration Center of Iranian Clinical Trials (www.irct.ir) under code of IRCT2013051313308N1 as a clinical trial. All participants provide signed informed consents.

RESULTS

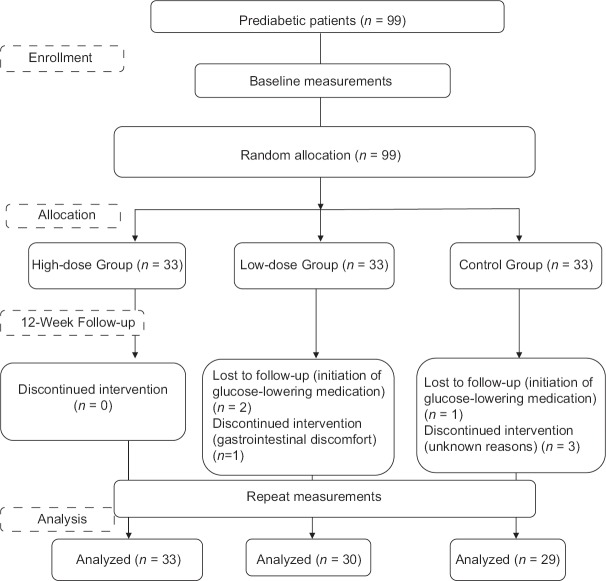

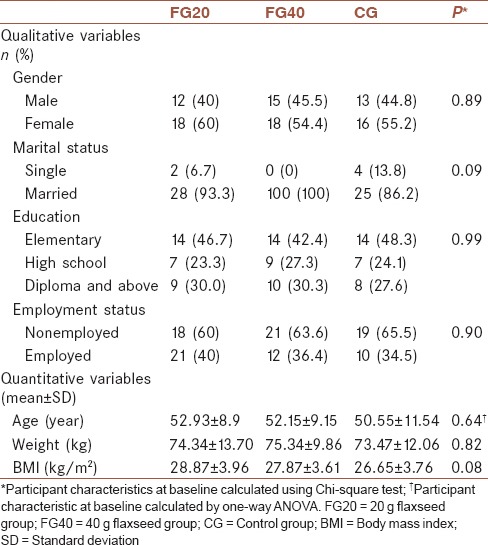

Ninety-two participants completed the study [Figure 1], and overall compliance by the participants was estimated as 93%. The baseline data were compared in three groups [Table 1]. There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of qualitative and quantitative variables at the baseline.

Figure 1.

Framework of trial

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of individuals in the three groups

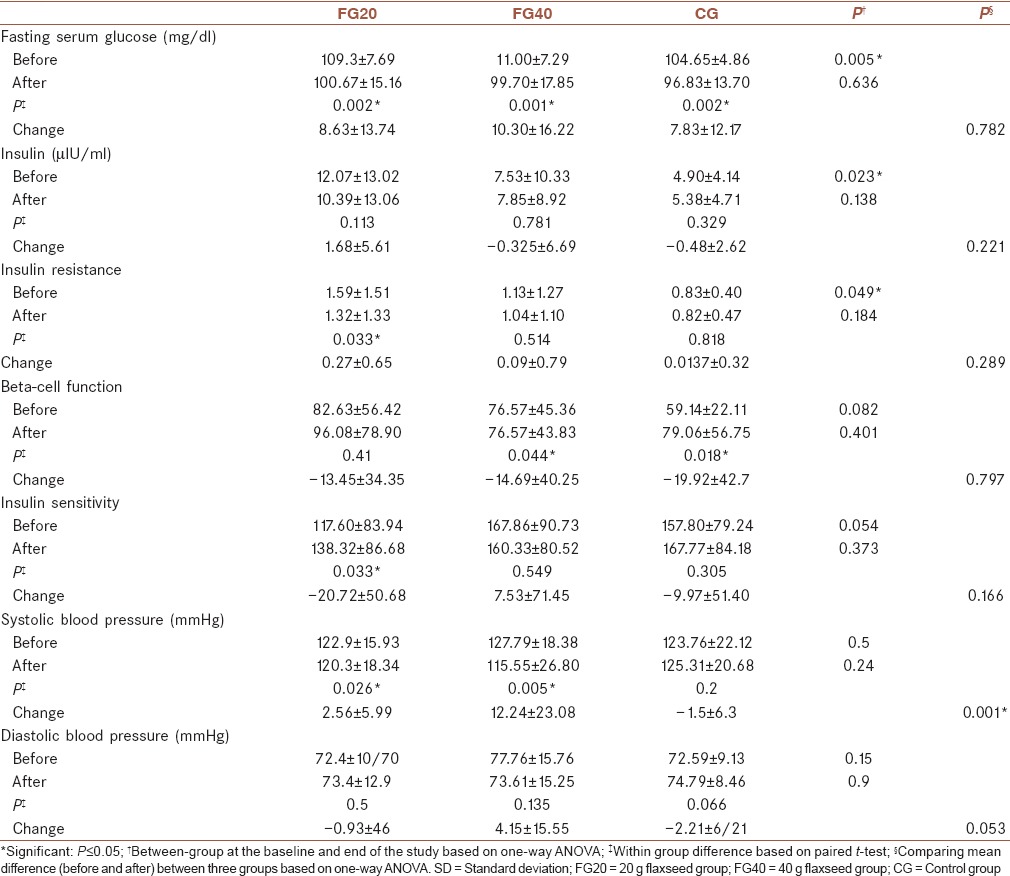

Comparisons of mean of glycemic and IR indices and blood pressure are shown in Table 2. As shown, FSG significantly declined overall in the three groups (P = 0.002 in CG and FG20 groups and P = 0.001 in FG40) compared to the baseline. In contrast, mean of the changes in FSG was not significant different between the three groups. Insulin concentration did not change significantly within the investigated groups compared to the baseline and also between the studied groups. Although it was showed a significant reduction in HOMA-IR (P = 0.033) in FG20, this difference was not significant between the three groups. Beta-cell function in all the groups increased compared to the baseline, which was significant only in CG and FG40 groups (P = 0.044 and P = 0.018, respectively). Mean of changes in beta-cell function did not show any significant difference between the three groups. Comparison of IS before and after the intervention showed a significant increase in IS only in FG20 group (P = 0.033). This difference was not significant in other groups before and after the intervention and also between the three groups.

Table 2.

Comparison of mean of glycemic, insulin resistance indices and blood pressure within and between three groups

Comparisons of mean of blood pressures are also shown in Table 2. FG40 group had significantly lowered systolic blood pressure at the end of the intervention (P = 0.005) than did FG20 group (P = 0.026) and CG group (P = 0.02) and compared to the baseline values.

DISCUSSION

The present research showed that 12-week supplementation of 20 g or 40 g flaxseed powder has not significantly reduced FSG, insulin concentration, HOMA-IR, beta-cell function, and IS but can reduce blood pressure in prediabetic individuals.

Benefits of flaxseed on glycemic control in prediabetes have not been well studied. To the best of our knowledge, very few studies have examined the effect of flaxseed on glycemic control in prediabetic people.[16,9] Other randomized clinical trials have reported flaxseed's influence on glycemic control in people who have type 2 diabetes[11,15] or are healthy[17,18] or in dyslipidemic people.[19,20,21]

A study conducted by Taylor et al. on individuals with well-controlled diabetes was consistent with the findings of the present study and showed that taking milled flaxseed and flaxseed oil supplement had no effect on glycemic control.[11] Further, in the studies where omega-3 supplementation was given to diabetic people, no effect of omega-3 on glycemic control was observed.[22] In Barre's study, flaxseed oil supplementation had no effect on glycemic control in diabetic patients.[23] Despite lack of change in fasting blood glucose and insulin concentration after supplementation with flaxseed, Pan et al. reported improvement in long-term glycemic control in diabetic patients.[15]

Different results may be due to different sample sizes,[9] different flaxseed doses,[9,16] differences in administration methods of flaxseed to people (baking in bread, milling, lignan extracted from flaxseed),[9,15,16] disease status of participants (type 2 diabetes, prediabetes, or hypercholesterolemia),[15,16,19] or lack of CG and different types of design.[9,16] Some studies, despite reduction in IR, are consistent with the present results due to the lack of changes in insulin levels.[9,15,24]

Although flaxseed supplementation appears to be ineffective for glycemic control in diabetic patients, in patients with prediabetes, despite the limited number of studies, a significantly positive effect of flaxseed on glycemic control has been found.[9,16] In a study published in 2013 by Hutchins et al., low dose (13 g/day) of flaxseed was shown to have a positive impact on fasting blood glucose in prediabetic individuals; however, flaxseed consumption showed no decline in long-term blood glucose levels.[16] Examining probable long-term impact of flaxseed on glycemic control requires further studies. In a study by Rhee and Brunt, obese patients with IR received 40 g milled flaxseed for 12 weeks and finally IR showed a significant decrease after the study.[9]

Studies by Hutchins et al. and Rhee and Brunt on people with prediabetes have demonstrated reduced HOMA-IR and IR after consuming flaxseed[9,16] as similar to the outcome of this study in FG20 group. It seems that flaxseed supplement at the early stages of diabetes has a positive impact on reducing IR; however, this intervention is ineffective at the diagnosis stage of diabetes. Effect of flaxseed on reduced IR can be predicted through two mechanisms: First, antioxidant impact of the fiber existing in flaxseed and second, effect of omega-3 content of this seed.

In the present trial, flaxseed consumption in FG40 group had significantly lowered systolic blood pressure at the end of the study than did FG20 group and CG group and compared to the baseline, but Stuglin and Prasad published inconsistent results with the findings of the present study and flaxseed consumption did not lower blood pressure in healthy humans.[25] On the other hand, Paschos et al. showed a significant reduction in blood pressure of hyperlipidemic men which is consistent with our results.[20]

In this study, since people with prediabetic did not use hypoglycemic medications, using these drugs was not a confounding factor. This issue was one of the strengths of this work.

However, the limitations of the study must be taken into consideration. Giving no placebo to CG is one of the limitations. Moreover, the changes observed in overweight and obese participants cannot necessarily be extrapolated to all prediabetic individuals. In sum, based on the findings of this study, flaxseed has no effects on glycemic control in patients with prediabetes and its recommendation as a dietary component for prediabetic patients requires further studies. Studying probable effect of flaxseed on long-term glycemic control as well as isolating lignan from flaxseed to separately observe effect of lignans and omega-3 in individuals with prediabetes should be continued in future studies. It is also suggested to measure indicators such as alpha linolenic acid (ALA) percentage, hemoglobin A1c, and inflammatory factors in future works.

CONCLUSION

Daily intake of flaxseed powder lowered blood pressure in prediabetes but did not improve glycemic and IR indices.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

AJ and HMKh contributed in the conception of the work, conducting the study, revising the draft, approval of the final version of the manuscript, and agreed for all aspects of the work AN contributed in the conception of the work, drafting and revising the draft, approval of the final version of the manuscript, and agreed for all aspects of the work. AD and MHE contributed in the conception of the work, analyzing data, revising the draft, approval of the final version of the manuscript, and agreed for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by the Head of International Campus of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences and also cooperation of Cardiovascular Research Center of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. We would like to thank all participants and the research assistants who participated in this project for their effort.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nathan DM, Davidson MB, DeFronzo RA, Heine RJ, Henry RR, Pratley R, et al. Impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance: Implications for care. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:753–9. doi: 10.2337/dc07-9920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tabák AG, Herder C, Rathmann W, Brunner EJ, Kivimäki M. Prediabetes: A high-risk state for diabetes development. Lancet. 2012;379:2279–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60283-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milman S, Crandall JP. Mechanisms of vascular complications in prediabetes. Med Clin North Am. 2011;95:309–25, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan A, Demark-Wahnefried W, Ye X, Yu Z, Li H, Qi Q, et al. Effects of a flaxseed-derived lignan supplement on C-reactive protein, IL-6 and retinol-binding protein 4 in type 2 diabetic patients. Br J Nutr. 2009;101:1145–9. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508061527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang P, Engelgau MM, Valdez R, Benjamin SM, Cadwell B, Narayan KM. Costs of screening for pre-diabetes among US adults: A comparison of different screening strategies. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2536–42. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.9.2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tudor-Locke C, Schuna JM., Jr Steps to preventing type 2 diabetes: Exercise, walk more, or sit less? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2012;3:142. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2012.00142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States, 2011. United states: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hadaegh F, Bozorgmanesh MR, Ghasemi A, Harati H, Saadat N, Azizi F. High prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes and abnormal glucose tolerance in the Iranian urban population: Tehran lipid and glucose study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:176. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rhee Y, Brunt A. Flaxseed supplementation improved insulin resistance in obese glucose intolerant people: A randomized crossover design. Nutr J. 2011;10:44. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-10-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nettleton JA, Katz R. N-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in type 2 diabetes: A review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:428–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor CG, Noto AD, Stringer DM, Froese S, Malcolmson L. Dietary milled flaxseed and flaxseed oil improve N-3 fatty acid status and do not affect glycemic control in individuals with well-controlled type 2 diabetes. J Am Coll Nutr. 2010;29:72–80. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2010.10719819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazza G, Biliaderis C. Functional properties of flax seed mucilage. J Food Sci. 2006;54:1302–5. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mozaffari-Khosravi H, Javidi A, Nadjarzade A, Dehghani A, Eftekhari M. The effect of consumptionof two various dose of flaxseed on anthropometric indices and oxidative stress in overweight and obese prediabetic individuals: A randomized controlled trial. TB; 2016;14:68–78. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhathena SJ, Velasquez MT. Beneficial role of dietary phytoestrogens in obesity and diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:1191–201. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.6.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan A, Sun J, Chen Y, Ye X, Li H, Yu Z, et al. Effects of a flaxseed-derived lignan supplement in type 2 diabetic patients: A randomized, double-blind, cross-over trial. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutchins AM, Brown BD, Cunnane SC, Domitrovich SG, Adams ER, Bobowiec CE. Daily flaxseed consumption improves glycemic control in obese men and women with pre-diabetes: A randomized study. Nutr Res. 2013;33:367–75. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hallund J, Ravn-Haren G, Bügel S, Tholstrup T, Tetens I. A lignan complex isolated from flaxseed does not affect plasma lipid concentrations or antioxidant capacity in healthy postmenopausal women. J Nutr. 2006;136:112–6. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dodin S, Cunnane SC, Mâsse B, Lemay A, Jacques H, Asselin G, et al. Flaxseed on cardiovascular disease markers in healthy menopausal women: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrition. 2008;24:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bloedon LT, Balikai S, Chittams J, Cunnane SC, Berlin JA, Rader DJ, et al. Flaxseed and cardiovascular risk factors: Results from a double blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008;27:65–74. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2008.10719676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paschos GK, Magkos F, Panagiotakos DB, Votteas V, Zampelas A. Dietary supplementation with flaxseed oil lowers blood pressure in dyslipidaemic patients. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;61:1201–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang W, Wang X, Liu Y, Tian H, Flickinger B, Empie MW, et al. Dietary flaxseed lignan extract lowers plasma cholesterol and glucose concentrations in hypercholesterolaemic subjects. Br J Nutr. 2008;99:1301–9. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507871649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rastmanesh R, Javidi A, Taleban FA, Kimaigar M, Mehrabi Y. Effects of fish oil on cytokines, glycemic control, blood pressure, and serum lipids in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Obes Weight Loss Ther. 2013;3:197. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barre DE, Mizier-Barre KA, Griscti O, Hafez K. High dose flaxseed oil supplementation may affect fasting blood serum glucose management in human type 2 diabetics. J Oleo Sci. 2008;57:269–73. doi: 10.5650/jos.57.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bloedon LT, Szapary PO. Flaxseed and cardiovascular risk. Nutr Rev. 2004;62:18–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stuglin C, Prasad K. Effect of flaxseed consumption on blood pressure, serum lipids, hemopoietic system and liver and kidney enzymes in healthy humans. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2005;10:23–7. doi: 10.1177/107424840501000103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]