Abstract

Some studies have suggested chemopreventive and therapeutic effects of quercetin (Q) on carcinogenesis. The aim of this review was to evaluate the association between Q and ovarian cancer risk among human researches and induced sensitivity to some types of chemotherapeutic drugs and antiproliferative effects of this flavonoid in the animals and cell lines studies. Data for this systematic review were achieved through searches of the MEDLINE (PubMed), Google Scholar, Science Direct, Scopus, Cochrane, SID, and Magiran databases for studies published up to May 2015. Relevant studies were reviewed based on Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Review and Meta analysis guidelines. From the total number of 220 papers obtained at the initial search, 13 publications including 1 prospective, 2 case -control, 1 animal, and 9 in vitro human and animal cancer cell lines studies were eligible. Despite findings in laboratory settings, results from the epidemiological studies commented that the potentially protective effects of Q not be able to significantly decrease ovarian cancer risk at levels commonly consumed (1.01–31.7 mg/day) in a typical diet. However, animal and in vitro studies suggest that Q exerts anticancer effects via inhibiting tumor growth, and angiogenesis, interrupt the cell cycle, and induce apoptosis. It is highlighted the need for more studies to be conducted.

Keywords: Ovarian cancer, quercetin, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Among women ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer death all over the world in 2013.[1] This cancer accounted for 4% of women cancer cases[2] that does not answer to chemotherapy protocol and surgery as well.[3]

Several factors including increasing age, null parity, early menarche, late menopause, and family history are known as ovarian cancer risk factors,[2] while pregnancy and breastfeeding decrease this risk.[2] Beside mentioned factors, diet has an important role in increasing or decreasing risks of some malignancy.[4,5,6,7] Consistent evidence indicated that ovarian cancer has an inverse association with higher intakes of fruits and vegetables, whereas higher consumption of total fat and meat is widely associated with increased risk.[8] Moreover, some evidence was shown potential anticancer properties of flavonoids, protective chemicals in plant foods, such as antioxidant, anti-estrogenic, antiproliferative, and anti-inflammatory.[8,9] Among flavonoids, quercetin (Q) is the most common flavonoid in nature[10] with a wide variety of biological activities[11] that mostly present in leafy vegetables, apples, onions, broccoli, tea, and berries.[12] Q as a cancer chemotherapeutic agent may arrest the cell cycle by affecting on some enzymes in this pathway such as inhibiting 1-phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase (PI kinase) activity and decreasing inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) concentration.[3] In addition, it can disrupt cell growth by interfering with act of DNA topoisomerase II.[13,14] Moreover, Q induces apoptosis of cancer cells and inhibits cell growth[14] and prevents or delays chemotherapy-resistance.[15] As high estrogen levels can be related to estrogen-dependent cancers like ovarian cancer, it was shown that Q can reduce the risk of these cancers by estrogen biosynthesis inhibition.[16]

Despite findings of animal and in vitro studies that showed the protective effect of Q on ovarian cancer cells,[1,2,3] human studies mentioned that Q may not be able to significantly decrease ovarian cancer risk.[8,9,17] Therefore, we conducted a systematic review to evaluate the scientific evidence of an association between Q and ovarian cancer risk among human researches and induced sensitivity to some types of chemotherapeutic drugs and antiproliferative effects of this flavonoid in the animals and cell lines.

METHODS

This systematic review methodology was performed based on the Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis statement recommendation.[4]

Data sources and searches

Data for this Systematic review were achieved through searches of the MEDLINE (PubMed), Google Scholar, Science Direct, Scopus, Cochrane, SID, and Magiran databases for studies published up to May 2015. All studies on the association between Q and ovarian cancer were included using the search terms (“Flavonoids” [Mesh] OR “Quercetin” [Mesh]) AND “Ovarian Neoplasms” [Mesh] as key words. No language, duration, region, and type of study restriction were applied.

Study selection criteria

All of the studies examining the association between Q as an exposure and ovarian cancer risk among human and sensitivity to the some types of chemotherapeutic drugs and anti-proliferative effects of this flavonoid in animals and cell lines researches as outcomes were included in this systematic review.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) No report on the Q intake or supplementation, (2) no report on the ovarian cancer risk or treatment, (3) no report on effect of Q on the ovarian cell lines growth or proliferation or drug resistance, and (4) no report on the association between the Q and ovarian cancer.

Study selection

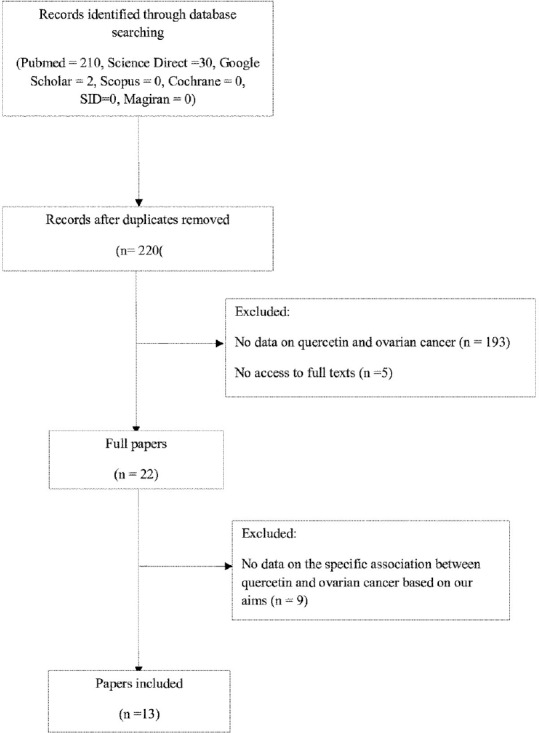

We could find 220 papers. Two investigators reviewed titles, abstracts, and full text. Further, for any pertinent survey, we screened the references of all included studies. Title and abstract of these studies were screened and 198 papers that did not report any information on the exposure or outcome of interest excluded. When full texts were screened, nine studies that did not mention the specific effect of Q on ovarian cancer was excluded. Finally, we included 13 papers in our systematic review to evaluate the association between Q consumption and ovarian cancer.

The level of agreement between investigators reached 90% according to Delphi process.

Detailed processes of the study selection were illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A flow chart of study selection

Data extraction

The extracted data from included papers were the first author's last name, publication year, study sample size, participants’ age, study period, dietary assessment, event followed, dose of treatment, and observed effects.

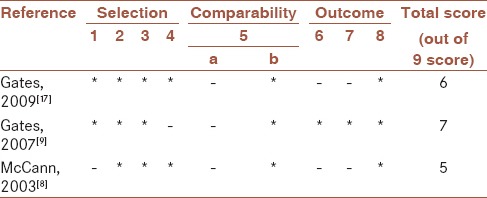

Quality assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used in order to judge about the quality of the included human studies on three broad perspectives: The selection of study groups, comparability of the groups, and ascertainment of either the exposure or outcome of interest. Summary scores of 0–2, 3–4, 5, and above it were rated as low, moderate, and high quality, respectively. Table 1 includes information about study-specific quality scores.

Table 1.

Quality assessment of the studies

RESULTS

Study characteristics

Characteristics of the selected articles were shown in Tables 2–4. The study design types were as follows: 1 prospective, 2 case–control, 1 animal, and 9 in vitro cell lines studies. The calculated quality scores of human studies ranged from 5 to 7. Therefore, three human studies ranged as high-quality studies.

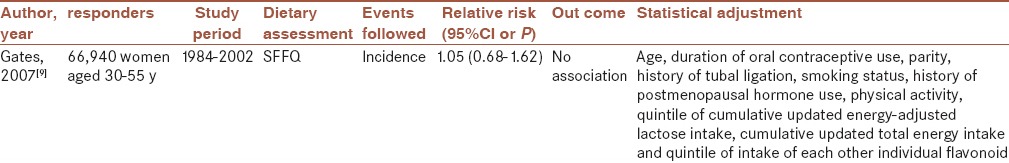

Table 2.

Characteristics of prospective studies about quercetin cancer risk

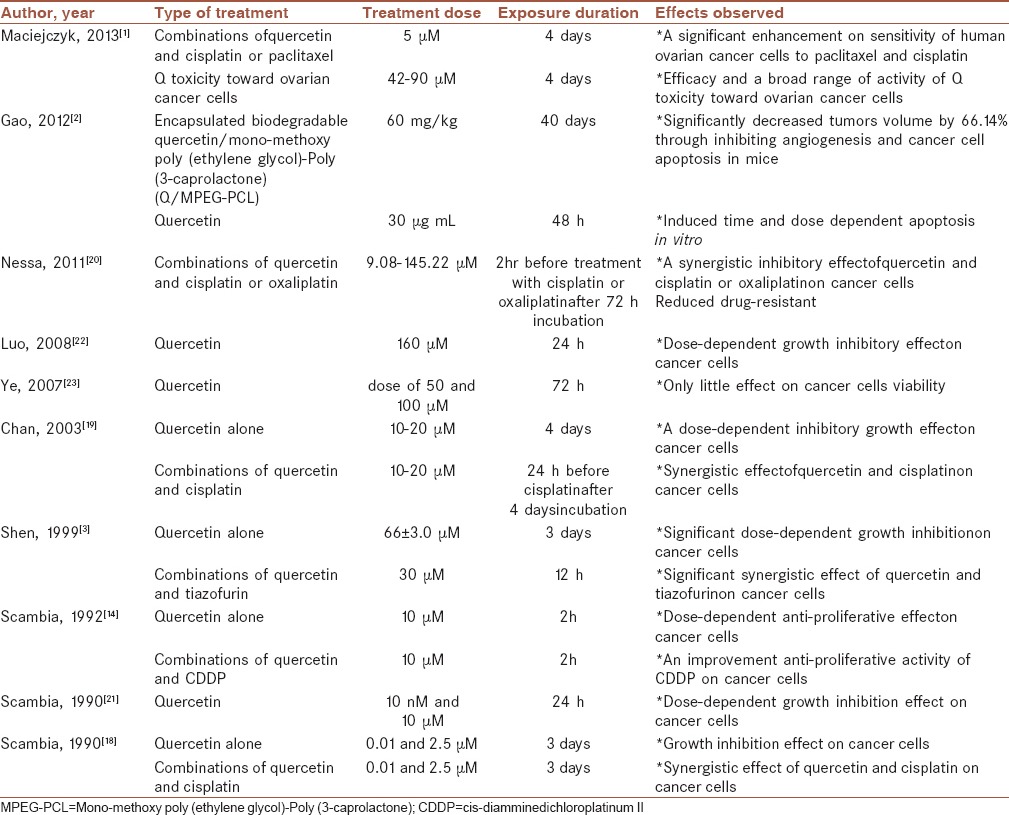

Table 4.

Characteristics of in vitro studies about quercetin cancer risk

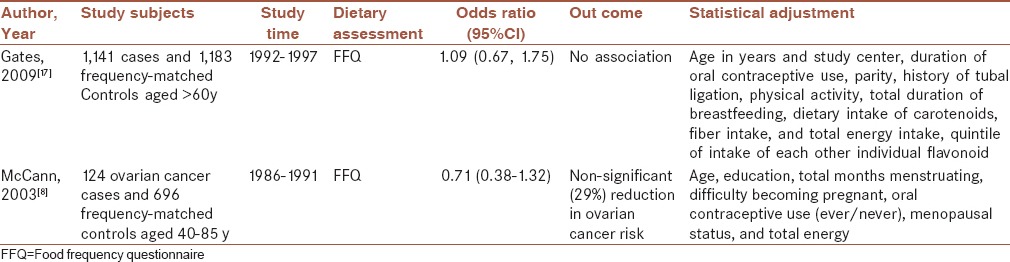

Table 3.

Characteristics of cross-sectional studies about quercetin cancer risk

Furthermore, although the mean score quality for all human articles considered was high, considering the risk of bias across studies such as publication bias, performance bias, reporting bias, and potential conflicts of interest are important. Therefore, more clinical trials and prospective cohort human studies with adequate sample size in developed and developing countries are needed.

Quercetin intake and ovarian cancer: Human studies

Gates et al. prospective study evaluated dietary Q intake and incidence of epithelial ovarian cancer. This study was performed on women aged 30–55 year that followed up 18 years. Semi-quantitative food frequency (SFFQ) was used for the assessment of Q dietary intake every 4 years. This study was shown no association between Q and incidence of ovarian cancer when the highest quintile was compared with the lowest quintile of Q intake even after multiple variable adjustment.[9]

Moreover, population-based case–control study conducted on ovarian cancer cases revealed that no significant relation between dietary Q intake and ovarian cancer risk when Q consumed to the lowest amount compared with the higher amount. As regards, onion consumption, as a major source of Q, was not assessed in this survey, this null association may be related to this limitation.[17]

These results were consistent with other study examining the relation between Q consumption and ovarian cancer risk. This case–control study performed on women included 124 incident, primary, histologically confirmed cases of ovarian cancer. Diet history of 2 years before the interview was asked with SFFQ.[8]

Quercetin intake and ovarian cancer: Animal studies

In contrast, in one animal studies intravenous administration of Q/MPEG-PCL micelles, water soluble forms of Q, could significantly decrease tumors volume by 66.14% through inhibiting angiogenesis and cancer cell apoptosis in mice.[2]

Quercetin intake and ovarian cancer: In vitro studies

Findings from one study that tested the synergistic effects of tiazofurin, as an anticancer drug, and Q against human carcinoma cells demonstrated that Q could have a significant dose-dependent growth inhibition on ovarian cancer cells. In addition, it could have a significant synergistic growth inhibition in a combination of tiazofurin followed 12 h later by Q on these cells.[3]

Another study was found the same effect of Q alone and in combination with cis-diamminedichloroplatinum II (CDDP), a chemotherapeutic agent, on sample cells obtained from four patients (29–65 years) with advanced ovarian cancer. Colony counting after treating cells with Q showed a growth inhibition ranging between 50 and 77%. Analyzing the simultaneous treatment with Q and CDDP by isobole method demonstrated Q could improve anti-proliferative activity of CDDP in all cases.[14]

Moreover, Scambia et al. reported that Q not only had a growth inhibition effect, but also had a synergistic effect on cisplatin in treating human ovarian cancer cell lines. These significant findings were approved by counting cells with the use of hemocytometer device.[18]

The same effect has been shown in another research when Q was added 24 h before cisplatin administration.[19]

In another study according to the IC50 values, Q concentration required for 50% cell kill, showed that administration of Q before treatment with cisplatin or oxaliplatin produced a synergistic inhibitory effect on human ovarian cancer cell growth and could reduce drug-resistant.[20]

Similar results obtained according to a report regarding the association between Q and sensitivity of some types of human ovarian cancer cells to paclitaxel and cisplatin as chemotherapeutic drugs.[1]

In this regard, finding from several studies suggested the positive association between the dose-dependent inhibitory effect of Q on human ovarian cancer cells proliferation.[21,22]

Further, although Q-induced time and dose-dependent apoptosis in human ovarian cancer cells with 56.3% reduction in cell viability,[2] another study showed only little effect on cell viability after treating cells with various concentrations of Q.[23]

DISCUSSION

Cancers’ rates continue to raise health and economic concerns around the globe and prevention interventions are necessary. Focusing on promoting healthier eating could be an effective way of reducing malignancy. This systematic review will provide information about the association between Q and ovarian cancer risk among human researches and induced sensitivity to some types of chemotherapeutic drugs and anti-proliferative effects of this flavonoid in the animals and cell lines.

According to our systematic review, evidence from in vitro studies[1,2,3] suggested that Q could inhibit tumor growth and angiogenesis, interrupt the cell cycle and induce apoptosis.[9] Despite findings in laboratory settings, results from the epidemiological studies[8,9,17] commented that the potentially protective effects of Q might not be able to significantly decrease ovarian cancer risk at commonly consumed levels in (1.01–31.7 mg/day) a typical diet.[12]

Protective effects of Q on cancer can be inserted through several important biological mechanisms.

The protective effects of quercetin on enzymes

Up-regulation of inositol monophosphate (PI) signal transduction pathway activity converting PI to secondary messengers, IP3 and diacylglycerol, is involved in malignancy. They were markedly elevated in various cancer cells, and these changes were linked with transformation and progression of neoplastic disease. As the Q is a cell cycle blocker that inhibits PI kinase in cancer cells, it may explain the anti-proliferative and cytotoxic action of Q in human ovarian cancer cells.[3]

The incidence of ovarian cancer might be due to the estrogen-rich environment surrounding the ovaries and the proliferative effect of estrogen on ovarian epithelial cells.[16] Studies have shown that Q could inhibit aromatase activity, a key enzyme in estrogen biosynthesis, and decrease estrogen concentration around the ovaries and via this pathway preventive effect of Q on cancer could be exerted.[16]

Furthermore, overproduction of protein kinase C1 (PKC1) has been associated to cancers[24] and the growth inhibitory effects of Q may be mediated by inhibition of PKC production.[11]

The effects of quercetin on receptors

Type II estrogen binding sites may be related to the control of cell growth. Since these receptors are occupied by an endogenous flavonoid-like ligand with growth inhibitory activity, it is possible that Q act as an antagonist for these sites and exerts an anti-proliferative effect on ovarian cancer cells.[21]

The effects of quercetin on gene expression

Q can lower the resistance to some drugs via decreasing expression of a nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) gene, as this resistance to drugs is associated with abnormal activation of NF-κB.[20]

The effects of quercetin on proteins production

Exposure to hyperthermia, elevated temperatures (from 42 ± 45°C), can produce apoptosis. In addition, one major aspect of heat exposure is the rapid and exclusive synthesis of highly conserved heat-shock proteins (HSPs). It has been demonstrated that tumor cells express elevated levels of HSP-70, which causes resistance to thermal stress. Therefore, agents that are able to inhibit HSP-70 production, like Q, could synergize the killing effect of HT.[11]

Moreover, Q could induce growth inhibitory activity in ovarian cancer cells by modulation of transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) production.[25] The TGFβ family is known to regulate cell proliferation and differentiation.[26]

The effects of quercetin on inflammation

It is clear that the tumor-promoting inflammatory environment is one of the major cancer hallmarks.[27] Q is able to inhibit macrophage proliferation and activation, tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1b protein expression and secretion and in this way, it can down-regulate the inflammatory response.[10]

The antioxidant effects of quercetin

The antioxidant and pro-oxidant effects of Q depend on the concentration of intracellular reduced glutathione (GSH). In an oxidative stress, in the presence of peroxidases, Q reacts with H2O2 to form a Q-quinone (QQ) that has a pro-oxidant effect. Its high reactivity toward protein thiols and DNA can cause cell damage and cytotoxicity. QQ also reacts with GSH to form relatively stable protein-oxidized Q adducts such as 6-glutathionyl-Q (6-GSQ) and 8-GSQ. The reversibility of this reaction allows the continuous breakdown of GSQ into GSH and QQ. In the high concentrations of GSH, QQ reacts with GSH to form GSQ again and QQ cannot cause its cytotoxic effects.[28]

Bioavailability and absorption of quercetin

Bioavailability and absorption kinetics of Q are widely different between sources. A major reason for this difference is the type of glycoside.[29] Q is thought to be poorly absorbed because the naturally occurring glycosides’ sugar moieties elevate the molecules’ hydrophilicity.[30] The Q glycosides enter the colon and are hydrolyzed to the aglycone by enterobacteria.[30] Therefore, the hydrolysis of the glycoside to the aglycone increases the absorption of Q.[10] Thus, the carbohydrate moiety is important in the bioavailability, absorption, and plasma levels of Q in the human body.[29]

In contrast, another study mentioned that the absorption of Q glycosides is inhibited by the absence of Na+, which is needed for active Na+ /glucose co-transport. This active transport offers a possible explanation for the high absorption of Q from onions.[31]

However, included studies in this review had some limitations. Lack of association among human studies may be related to using of single FFQ and misclassification of Q intake values for specific questionnaire because of the omission of important Q sources or inaccuracies in its calculations in these researches.[9] In addition, Q levels commonly consumed (1.01–31.7 mg/day) in a normal diet are noticeably lower than that used as a supplement or drug in laboratory settings.[12] However, the retrospective and self-reported nature of the data collection increased the risk of bias in these studies.

Moreover, in vitro studies do not reflect all the aspect of in vivo application of a treatment as most in vitro models consider single cell types, metabolic pathway, or enzyme involvement. Another disadvantage of in vitro studies is that only acute or immediate effects can be measured, while effects that may appear after chronic exposure to the Q.

In addition, beside the study heterogeneity in the outcomes reported and populations investigated that precluded synthesis of the data, we should consider the risk of bias of systematic review including publication, time lag, location, citation, language, and outcome reporting biases.[14]

Hence, well-designed cohort and randomized clinical trial studies are needed to further evaluate these associations.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we found the no significant association between Q and anticancer effects among epidemiological findings. However, animal and in vitro studies suggest that Q exerts these effects via inhibit tumor growth, angiogenesis, interrupt the cell cycle, and induce apoptosis. It is highlighted the need for more studies to be conducted.

Financial support and sponsorship

We express our thankfulness to the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTION

AP, RR, NR, RGh and MM conceptualized and designed the study and drafted the manuscript.

AP, RR, NR, RGh, MP and MM contributed in conducting the study, revising the draft, approval of the final version of the manuscript, and agreed for all aspects of the work.

MM is the guarantor of this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maciejczyk A, Surowiak P. Quercetin inhibits proliferation and increases sensitivity of ovarian cancer cells to cisplatin and paclitaxel. Ginekol Pol. 2013;84:590–5. doi: 10.17772/gp/1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao X, Wang B, Wei X, Men K, Zheng F, Zhou Y, et al. Anticancer effect and mechanism of polymer micelle-encapsulated quercetin on ovarian cancer. Nanoscale. 2012;4:7021–30. doi: 10.1039/c2nr32181e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen F, Herenyiova M, Weber G. Synergistic down-regulation of signal transduction and cytotoxicity by tiazofurin and quercetin in human ovarian carcinoma cells. Life Sci. 1999;64:1869–76. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farsinejad-Marj M, Talebi S, Ghiyasvand R, Miraghajani M. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of breast cancer in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Arch Iran Med. 2015;18:786–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Golpour S, Rafie N, Safavi SM, Miraghajani M. Dietary isoflavones and gastric cancer: A brief review of current studies. J Res Med Sci. 2015;20:893–900. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.170627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jolfaie NR, Mirzaie S, Ghiasvand R, Askari G, Miraghajani M. The effect of glutamine intake on complications of colorectal and colon cancer treatment: A systematic review. J Res Med Sci. 2015;20:910–8. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.170634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rafie N, Golpour Hamedani S, Ghiasvand R, Miraghajani M. Kefir and cancer: A systematic review of literatures. Arch Iran Med. 2015;18:852–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCann SE, Freudenheim JL, Marshall JR, Graham S. Risk of human ovarian cancer is related to dietary intake of selected nutrients, phytochemicals and food groups. J Nutr. 2003;133:1937–42. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.6.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gates MA, Tworoger SS, Hecht JL, De Vivo I, Rosner B, Hankinson SE. A prospective study of dietary flavonoid intake and incidence of epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:2225–32. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Comalada M, Camuesco D, Sierra S, Ballester I, Xaus J, Gálvez J, et al. In vivo quercitrin anti-inflammatory effect involves release of quercetin, which inhibits inflammation through down-regulation of the NF-kappaB pathway. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:584–92. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piantelli M, Tatone D, Castrilli G, Savini F, Maggiano N, Larocca LM, et al. Quercetin and tamoxifen sensitize human melanoma cells to hyperthermia. Melanoma Res. 2001;11:469–76. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L, Lee IM, Zhang SM, Blumberg JB, Buring JE, Sesso HD. Dietary intake of selected flavonols, flavones, and flavonoid-rich foods and risk of cancer in middle-aged and older women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:905–12. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cantero G, Campanella C, Mateos S, Cortés F. Topoisomerase II inhibition and high yield of endoreduplication induced by the flavonoids luteolin and quercetin. Mutagenesis. 2006;21:321–5. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gel033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scambia G, Ranelletti FO, Benedetti Panici P, Piantelli M, Bonanno G, De Vincenzo R, et al. Inhibitory effect of quercetin on primary ovarian and endometrial cancers and synergistic activity with cis-diamminedichloroplatinum (II) Gynecol Oncol. 1992;45:13–9. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(92)90484-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen SS, Michael A, Butler-Manuel SA. Advances in the treatment of ovarian cancer: A potential role of antiinflammatory phytochemicals. Discov Med. 2012;13:7–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu DF, Yang LJ, Wang F, Zhang GL. Inhibitory effect of luteolin on estrogen biosynthesis in human ovarian granulosa cells by suppression of aromatase (CYP19) J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:8411–8. doi: 10.1021/jf3022817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gates MA, Vitonis AF, Tworoger SS, Rosner B, Titus-Ernstoff L, Hankinson SE, et al. Flavonoid intake and ovarian cancer risk in a population-based case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1918–25. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scambia G, Ranelletti FO, Benedetti Panici P, Bonanno G, De Vincenzo R, Piantelli M, et al. Synergistic antiproliferative activity of quercetin and cisplatin on ovarian cancer cell growth. Anticancer Drugs. 1990;1:45–8. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199010000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan MM, Fong D, Soprano KJ, Holmes WF, Heverling H. Inhibition of growth and sensitization to cisplatin-mediated killing of ovarian cancer cells by polyphenolic chemopreventive agents. J Cell Physiol. 2003;194:63–70. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nessa MU, Beale P, Chan C, Yu JQ, Huq F. Synergism from combinations of cisplatin and oxaliplatin with quercetin and thymoquinone in human ovarian tumour models. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:3789–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scambia G, Ranelletti FO, Panici PB, Piantelli M, Bonanno G, De Vincenzo R, et al. Inhibitory effect of quercetin on OVCA 433 cells and presence of type II oestrogen binding sites in primary ovarian tumours and cultured cells. Br J Cancer. 1990;62:942–6. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1990.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo H, Jiang BH, King SM, Chen YC. Inhibition of cell growth and VEGF expression in ovarian cancer cells by flavonoids. Nutr Cancer. 2008;60:800–9. doi: 10.1080/01635580802100851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ye B, Aponte M, Dai Y, Li L, Ho MC, Vitonis A, et al. Ginkgo biloba and ovarian cancer prevention: Epidemiological and biological evidence. Cancer Lett. 2007;251:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray NR, Kalari KR, Fields AP. Protein kinase C. expression and oncogenic signaling mechanisms in cancer? J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:879–87. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scambia G, Panici PB, Ranelletti FO, Ferrandina G, De Vincenzo R, Piantelli M, et al. Quercetin enhances transforming growth factor beta 1 secretion by human ovarian cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 1994;57:211–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910570214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Francis-Thickpenny KM, Richardson DM, van Ee CC, Love DR, Winship IM, Baguley BC, et al. Analysis of the TGF beta functional pathway in epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:687–91. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raposo TP, Beirão BC, Pang LY, Queiroga FL, Argyle DJ. Inflammation and cancer: Till death tears them apart. Vet J. 2015;205:161–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gibellini L, Pinti M, Nasi M, Montagna JP, De Biasi S, Roat E, et al. Quercetin and cancer chemoprevention. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2011. 2011 doi: 10.1093/ecam/neq053. 591356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hollman PC, van Trijp JM, Buysman MN, van der Gaag MS, Mengelers MJ, de Vries JH, et al. Relative bioavailability of the antioxidant flavonoid quercetin from various foods in man. FEBS Lett. 1997;418:152–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bentz A. A Review of quercetin: Chemistry, antioxidant properties, and bioavailability. J Young Investig. 2009;4:34–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hollman PC, de Vries JH, van Leeuwen SD, Mengelers MJ, Katan MB. Absorption of dietary quercetin glycosides and quercetin in healthy ileostomy volunteers. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;62:1276–82. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.6.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]