Abstract

Background:

Seborrheic keratosis (SK) is the most common benign epidermal tumor of the skin. Even though SK has been well characterized clinically, dermoscopically, and histopathologically, data regarding clinical dermoscopic and histopathological correlation of different types of SK are inadequate.

Aim:

We carried out this study to establish any correlation between the clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathological appearance of SK and its variants.

Methods:

This was a descriptive study. Patients with SK were evaluated with respect to age, sex, family history of similar lesions, site of lesions, and symptoms associated with the lesions. Dermoscopy was performed in all cases. Biopsies were taken from the lesions and assessed for histopathology.

Results:

The most common age group affected by SK was 31–50 years (42%). A female preponderance of 76% was seen. Majority of our patients had a positive family history (62%), though Sun exposure was not seen to be a major factor. The most common clinical variant was common SK (CSK) (46%). The most common dermoscopic findings seen in CSK were comedo-like (CL) openings, fissures and ridges (FR), and milia-like (ML) cysts. Dermatosis papulosa nigra and pedunculated SK had characteristic FR and CL openings on dermoscopy. Stucco keratoses showed network-like (NL) structures and sharp demarcation. CL opening on dermoscopy corresponded to papillomatosis and pigmentation, ML cysts corresponded to horn cysts, FR corresponded to papillomatosis, and NL structures corresponded to an increase in basal layer pigmentation.

Conclusions:

This study emphasizes the use of dermoscopy in improving the diagnostic accuracy of SK. The correlation between the various histological and dermoscopic features is described.

Keywords: Benign epidermal tumor, dermoscopy, histopathology, seborrheic keratosis

Introduction

What was known?

Studies done on correlation of the dermoscopy and histopathological findings have shown that the histopathological features mainly form the anatomic basis for the various dermoscopic features.

Seborrheic keratosis (SK) is the most common benign epidermal tumor of the skin and a frequent focus of patient concern because of its variable appearance.[1] The condition is more common in Caucasians and in the elderly. Males and females are equally affected.

The lesions of SK can occur at any site over the body, but are most frequent on the face and upper trunk. The lesions are usually asymptomatic, but may be itchy.[2] Although there are many clinical variants of the lesions, these lesions usually begin as well-circumscribed, dull, flat, tan, or brown patches. As they grow, they become more papular, taking on a waxy verrucous or “stuck-on” appearance.[1]

Even though SK is presently one of the most common cosmetic skin complaints, there is a lack of data relating to its clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathologic correlation. This study may provide useful information regarding the etiology and pathology of SK.

Methods

The study was conducted in the Dermatology Out-patients Department, Father Muller Medical College Hospital, Mangalore, from October 2013 to March 2015. Patients with clinical diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis, who were above 18 years and were willing to participate in the study, were included. A written informed consent was taken from all patients. Patients with SK were evaluated with respect to age, sex, age of onset, duration, family history of similar lesions, site of lesions, number of lesions, morphology, and symptoms associated with the lesions. Dermoscopic examination was performed in all cases in randomly chosen pigmented lesions. An incisional or punch biopsy was taken from the lesions and assessed for histopathology.

The data were analyzed by percentage, frequency, Chi-square test, predictability, sensitivity, specificity, and Fisher's exact test.

Results

A total of fifty patients were studied. It was seen that maximum number of patients were in the age group of 31–50 years (42%). Females (76%) outnumbered males (24%) in our study group. A positive family history was seen in 31 out of the fifty patients (62%). Most of the lesions were present in areas not exposed to Sunlight such as chest, back, abdomen, thighs, and legs (62%). Itching was seen only in 26% of the patients.

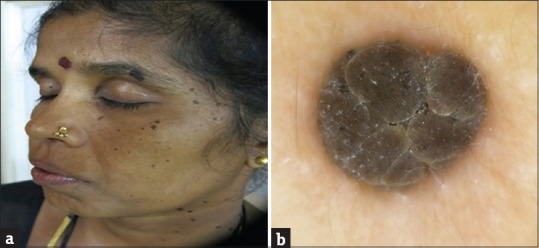

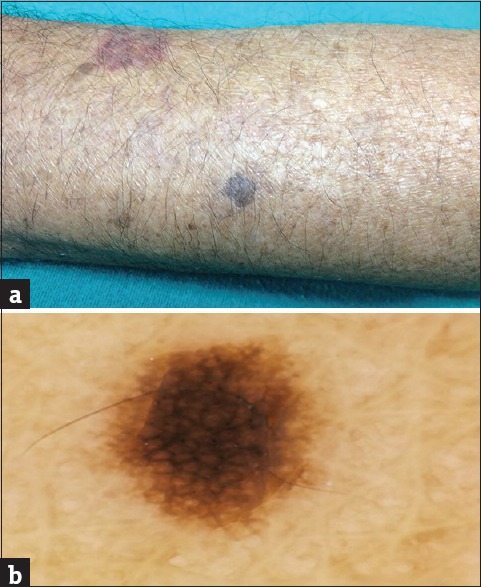

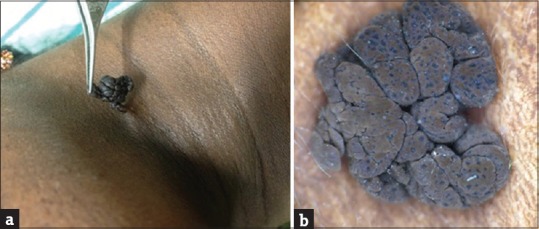

Our study showed the highest incidence of common SK (CSK) (46%) [Figure 1], followed by dermatosis papulosa nigra (DPN) (26%) [Figure 2a], followed by stucco keratoses (18%) [Figure 3a] and pedunculated variety (10%) [Figure 4a].

Figure 1.

Common seborrheic keratosis

Figure 2.

(a) Dermatosis papulosa nigra. (b) Dermoscopy showing fissures and ridges giving cerebriform appearance

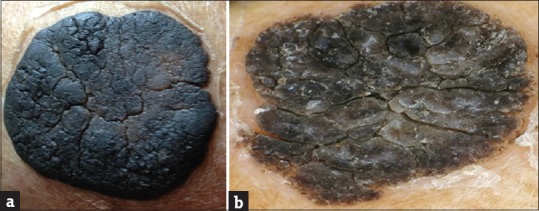

Figure 3.

(a) Stucco keratosis. (b) Dermoscopy showing network-like structures

Figure 4.

(a) Pedunculated seborrheic keratosis. (b) Dermoscopy showing comedo-like openings and fissures and ridges

The presence of comedo-like (CL) openings (68%) was the most common finding on dermoscopy followed by fissures and ridges (FR) (62%) and sharp demarcation (SD) (62%). Network-like (NL) structures were seen in 40% of the cases, milia-like (ML) cysts in 38% of the cases, moth-eaten (ME) border in 26% of the cases, and fingerprint (FP)-like structures in 6% of the cases. Hairpin (HP) blood vessels were not seen in any of our patients.

Pigmentation was the most common feature on histopathology being seen in 78% of the cases followed by papillomatosis in 68% of the cases, acanthosis in 56% of the cases, hyperkeratosis in 54% of the cases, and horn cyst formation in 44% of the cases.

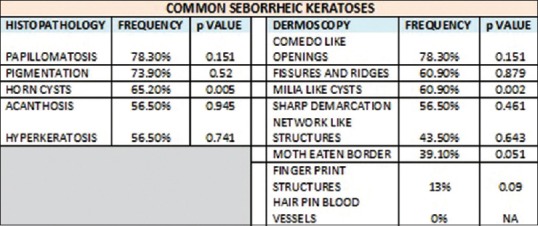

The most common histopathological feature seen in CSK was papillomatosis (78.30%), other features seen were pigmentation (73.90%), horn cysts (65.20%), acanthosis and hyperkeratosis (56.50%). The presence of horn cysts was statistically significant (P = 0.005). The most common dermoscopic findings seen in CSK were CL openings (78.3%), FR and ML cysts (60.9%), and other findings included SD (56.5%), NL structures (43.5%), ME border (39.1%), and FP-like structures (13%). Presence of ML cysts was statistically significant (P = 0.002).

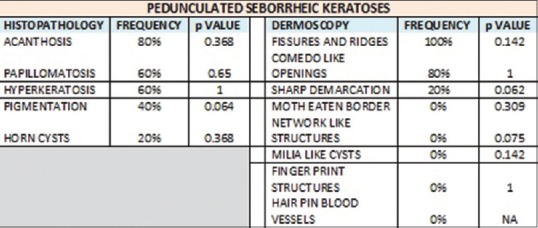

The most common histopathological features seen in DPN were papillomatosis and pigmentation (84.6%) followed by acanthosis and hyperkeratosis (53.8%). Horn cysts were seen only in 7.7% of the cases and its absence was statistically significant (P = 0.002). The most common dermoscopic features seen in DPN were FR and CL openings (92.3%) followed by SD in 69.2% of the cases [Figure 2b]. NL structures and ME borders were seen in only 7.7% of the cases. ML cysts were not seen in any of the cases. The presence of FR (P = 0.009) and CL openings (P = 0.039) was statistically significant and also was the absence of ML cysts (P = 0.001).

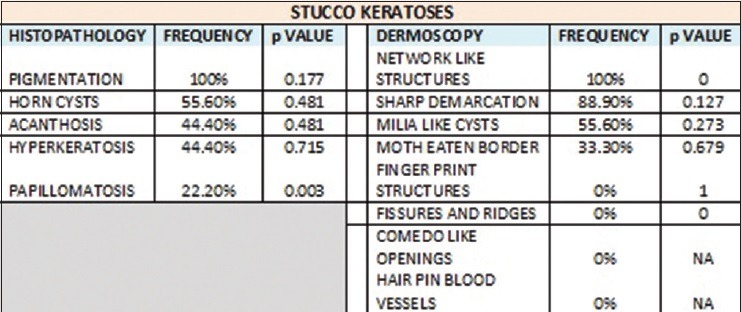

The most common histopathological feature seen in stucco keratoses was pigmentation, which was present in 100% of the cases followed by the presence of horn cysts (55.6%), acanthosis and hyperkeratosis (44.4%), and papillomatosis in 22.2% of the cases. The absence of papillomatosis was statistically significant (P = 0.003). The most common dermoscopic feature was NL structures (100%) followed by SD (88.9%), ML cysts were seen in 55.6% of the cases, and ME border was seen in 33.3% of the cases [Figure 3b]. FP structures, FR and CL openings were absent. Presence of NL structures was statistically significant (P = 0) and so was the absence of FR and CL openings (P = 0).

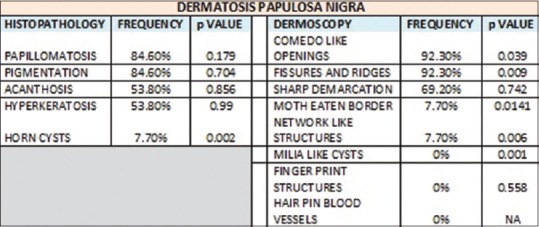

The most common histopathological feature seen in pedunculated SK was acanthosis (80%) followed by papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis (60%), pigmentation (40%), and horn cysts (20%). The most common feature seen on dermoscopy was FR (100%) followed by CL openings (80%), SD (20%), NL structures, ME borders, FP-like structures, ML cysts, and HP blood vessels were absent [Figure 4b].

CL opening on dermoscopy corresponded to papillomatosis (91.2%) (P = 0) and pigmentation (67.6%) (P = 0.01) and was statistically significant. Other features present were horn cysts in 32.40% of the cases, acanthosis in 64.70% of the cases, and hyperkeratosis in 55.90% of the cases. ML cysts on dermoscopy corresponded to horn cysts (100%) (P = 0) and was statistically significant. Other features seen in association with ML cysts were papillomatosis in 63.20% of the cases, pigmentation in 89.50% of the cases, acanthosis in 52.60% of the cases, and hyperkeratosis in 52.60% of the cases. FR on dermoscopy corresponded to papillomatosis (87.1%) (P = 0) and was statistically significant. Other features seen were horn cysts in 32.30% of the cases, pigmentation in 74.20% of the cases, acanthosis in 18% of the cases, and hyperkeratosis in 58.10% of the cases.

FP-like structures corresponded to papillomatosis (100%), horn cysts (100%), pigmentation (33.30%), acanthosis (100%), and hyperkeratosis (66.70%), but none of these were statistically significant.

ME border on dermoscopy corresponded to papillomatosis (76.90%), horn cysts (61.50%), pigmentation (84.60%), acanthosis (46.20%), and hyperkeratosis (38.50%), but none was statistically significant. NL structures corresponded to pigmentation (95%) (P = 0.033) and was statistically significant. Other features seen were papillomatosis (55%), horn cysts (60%), acanthosis (50%), and hyperkeratosis (40%). SD corresponded to pigmentation (80.6%), papillomatosis (64.50%), horn cysts (48.40%), acanthosis (54.80%), and hyperkeratosis (38.70%), but none was statistically significant.

Discussion

SK has been seen to occur in middle-aged individuals.[3] A study conducted in Australia by Yeatman et al. on 100 participants reported an increase in the prevalence of SK from 12% of 15–25 years old to 100% of those aged more than 50 years.[4] A Korean study by Kwon et al. has reported that 88.1% of the Korean males aged 40–70 years had at least one lesion.[5] The peak incidence of SK in our study was 31–50 years (42%).

Gender distribution of SK is balanced.[6] In some studies, a slight female preponderance of the DPN variant was seen.[3] A female preponderance of 76% seen in our study could be due to the fact that women usually seek dermatological advice due to the cosmetic concern more than men.

Many different factors from time to time have been implicated in the etiology of SK, but none is well understood. Genetics and Sun exposure have been implicated as the major causes.[7,8] Majority of our patients had a positive family history (62%), though Sun exposure was not seen to be a major factor in our study as 62% of our patients had lesions in covered areas such as chest, abdomen, back, thighs, and legs. This was in contrast to a study conducted on Korean males by Kwon et al. on 303 volunteers aged 40–70 years, which showed cumulative Sunlight exposure to be a contributing factor.[5]

Itching has been reported in a few cases of SK.[3] In our study, only 13 patients, i.e., 26% had itching, out of which two patients had severe agonizing pruritus.

Eruptive SK is known as a sign of internal malignancy, which is called the Leser–Trelat sign or seen with noncancerous conditions such as inflammatory dermatoses and drug reactions.[9,10] One of our patients, a 35-year-old women had developed multiple SK lesions over the abdomen, thighs, back, and arms in 3 months. She gave a history of esophageal carcinoma in her father. She was evaluated with relevant history, routine blood tests, and ultrasonography, but all were within normal limits.

Giant SK is very rare. We had a case of a giant SK measuring about 5 cm × 4 cm in size over the left breast [Figure 5a]. This on dermoscopy showed a parched paddy field appearance, which is a new finding [Figure 5b].

Figure 5.

(a) Giant seborrheic keratosis. (b) Dermoscopy showing fissures and ridges, sharp demarcation, and moth-eaten border

Multiple facial SK-like lesions in a young woman with epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EDV) have been reported.[11] We also had a similar case of EDV with SK-like lesions over arms and face.

A study conducted in South India by Rajesh et al. has reported the frequency of occurrence of various clinical types of SK, CSK being the most common (60%), followed by DPN (46.6%), pedunculated SK (21.2%), and stucco keratoses (2%).[3] Our study also showed the highest incidence of CSK (46%), followed by DPN (26%). We had a higher incidence of stucco keratoses (18%) compared to pedunculated variety (10%).

Dermoscopy

SKs are among the most common of the pigmented lesions. Dermatoscopy helps in the diagnosis of many pigmented skin lesions such as SK, pigmented basal cell carcinoma, hemangioma, blue nevus, atypical nevus, and cutaneous melanoma.[12] It is 10–27% more sensitive than the clinical criteria of ABCD (asymmetry, border regularity, color distribution, and diameter) in the early diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma.[13,14] Dermatoscopy of melanocytic lesions increases the presurgical accuracy rate of clinical diagnosis from 50% to 85%.[15,16] It was found that dermatoscopy raised the rate of diagnostic accuracy for pigmented BCC from 60% to 90%.[17]

The diagnosis of SK is mostly a clinical diagnosis, but in certain percentage of cases, differential diagnosis between SK and malignant melanoma is difficult.[12] The dermoscopic finding of the NL structures (46%) should not be confused with the typical pigment network as seen in melanocytic lesions.[18]

Dermoscopic findings of SK include ML cysts, CL openings, FR, ME borders, HP blood vessels, FP-like structures, and SD.[3]

Only few studies have been done on the dermoscopy of SK. Braun et al. in a study evaluated 203 pigmented SK and reviewed the dermoscopic criteria. The authors found a high prevalence of classic dermoscopic criteria such as CL openings (71%) and ML cysts (66%). The authors have suggested that in addition to these other dermoscopic criteria such as FR (61%), HP blood vessels (63%), SD (90%), and ME border (46%) would improve the diagnostic accuracy and reduce the misclassification into melanocytic lesions.[18]

Our study showed CL openings (68%) to be the most common finding on dermoscopy followed by FR (62%) and SD (62%). NL structures were seen in 40% of the cases, ML cysts in 38% of the cases, ME border in 26% of the cases, and FP-like structures in 6% of the cases. HP blood vessels were not seen in any of our patients. This finding is similar to a study done in South India and has been attributed to the brown-colored Asian skin through which the blood vessels cannot be seen.[3]

A study conducted by Rajesh et al. evaluated a total of 250 cases of SK for all the dermoscopic criteria in different clinical variants of SK. It was seen that CL openings (80%), FR (52%), and SD (82.6%) were the consistent findings on dermoscopy in CSK and the less common findings were ME borders (31.3%), ML cysts (24%), and NL structures (4%). DPN showed only three findings, CL openings (85.3%), FR (78.4%), and SD (17.2%). Pedunculated SK showed only two findings, FR in all lesions (100%) and CL openings (64.1%). Stucco keratoses demonstrated SD and NL structures in all cases (100%), ML cysts in two cases, and ME border in one case.[3]

We studied the various dermoscopic findings for each clinical type, and the presence or absence of these features could help in diagnosing each type of SK and hence, in deciding the treatment options.

Our study showed that the most common dermoscopic findings seen in CSK were the presence of CL openings (78.3%), FR (60.9%), ML cysts (60.9%), and the less common findings were SD (56.5%), NL structures (43.5%), ME border (39.1%), and FP structures (13%). Presence of ML cysts was statistically significant (P = 0.002). The most common dermoscopic features seen in DPN were FR and CL openings (92.3%) followed by SD in 69.2% of the cases. NL structures and ME borders were seen in only 7.7% of the cases. ML cysts were not seen in any of the cases. The presence of FR (P = 0.009) and CL openings (P = 0.039) was statistically significant and also was the absence of ML cysts (P = 0.001). The most common dermoscopic feature in stucco keratoses was NL structures (100%) followed by SD (88.9%), ML cysts were seen in 55.6% of the cases, and ME border in 33.3% of the cases. FP structures, FR and CL openings were absent. Presence of NL structures was statistically significant (P = 0) and so was the absence of FR and CL openings (P = 0). The most common dermoscopic feature seen in pedunculated SK was FR (100%) followed by CL openings (80%), and SD (20%).

Histopathology

The knowledge of the spectrum of histology of SK will help in understanding the dermoscopic features encountered. Each type of SK demonstrates varying degrees of acanthosis, pigmentation, horn cysts formation, hyperkeratosis, and papillomatosis, when viewed histologically.[19]

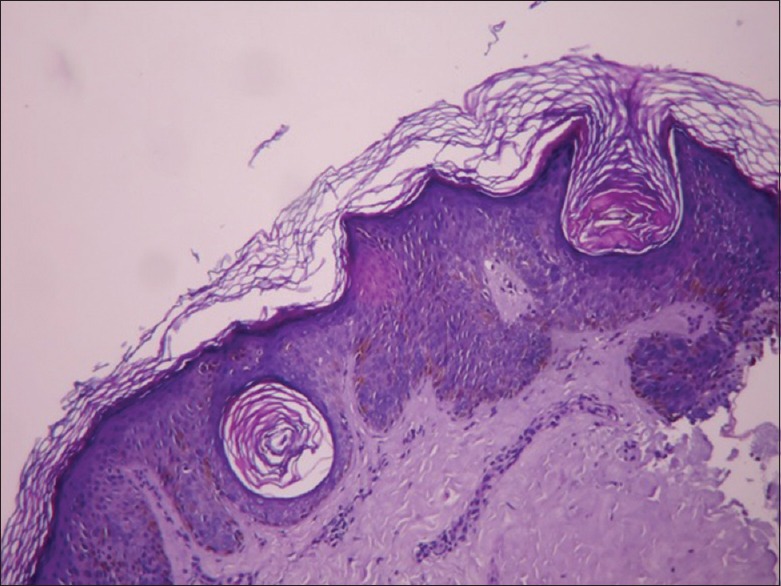

Our study also showed these to be the most common findings on histopathology with pigmentation (78%) being the most common followed by papillomatosis (68%), acanthosis (56%), hyperkeratosis (54%), and horn cyst formation (44%) [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, horn cysts, basal layer pigmentation

The histopathological features seen in CSK in our study were papillomatosis (78.30%), pigmentation (73.90%), horn cysts (65.20%), acanthosis and hyperkeratosis (56.50%). The presence of horn cysts was statistically significant (P = 0.005). The histopathological features seen in DPN were papillomatosis, pigmentation (84.6%), acanthosis and hyperkeratosis (53.8%). Horn cysts were seen only in 7.7% of the cases and its absence was statistically significant (P = 0.002). The histopathological features seen in stucco keratoses were pigmentation, which was present in 100% of the cases followed by the presence of horn cysts (55.6%), acanthosis and hyperkeratosis (44.4%), and papillomatosis in 22.2% of the cases. The absence of papillomatosis was statistically significant (P =0.003). The histopathological features seen in pedunculated SK were acanthosis (80%), followed by papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis (60%), pigmentation (40%), and horn cysts (20%), but none was statistically significant.

Studies done on correlation of the dermoscopy and histopathological findings have shown that the histopathological features mainly form the anatomic basis for the various dermoscopic features. The presence of papillomatosis which is the variation in epidermal height accounts for CL openings and FR, which are two typical dermoscopic findings in SK. The presence of ML cysts histologically corresponded with keratin-filled cysts, known as horn cysts.[19]

Our study also showed similar findings. CL opening on dermoscopy corresponded to papillomatosis (91.2%) (P = 0) and pigmentation (67.6%) (P = 0.01) and was statistically significant. ML cysts on dermoscopy corresponded to horn cysts (100%) (P = 0) and was statistically significant. FR on dermoscopy corresponded to papillomatosis (87.1%) (P = 0) and was statistically significant. NL structures corresponded to pigmentation (95%) (P = 0.03) and was statistically significant [Figures 7–10].

Figure 7.

Dermoscopic and histopathological features seen in common seborrheic keratosis

Figure 10.

Dermoscopic and histopathological features seen in pedunculated seborrheic keratosis

Figure 8.

Dermoscopic and histopathological features seen in dermatosis papulosa nigra

Figure 9.

Dermoscopic and histopathological features seen in stucco keratosis

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

Comedo like opening on dermoscopy corresponded to papillomatosis and pigmentation, Miia Like cysts corresponded to horn cysts, Fissure and Ridges corresponded to papillomatosis and Network like structures corresponded to pigmentation.

References

- 1.Perkins W, Quinn AG. Non-melanoma skin cancer and other epidermal skin tumours. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2010. pp. 521–48. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reiches AJ. Seborrheic keratoses; are they delayed hereditary nevi? AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1952;65:596–600. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1952.01530240088011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajesh G, Thappa DM, Jaisankar TJ, Chandrashekar L. Spectrum of seborrheic keratoses in South Indians: A clinical and dermoscopic study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:483–8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.82408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeatman JM, Kilkenny M, Marks R. The prevalence of seborrhoeic keratoses in an Australian population: Does exposure to sunlight play a part in their frequency? Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:411–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwon OS, Hwang EJ, Bae JH, Park HE, Lee JC, Youn JI, et al. Seborrheic keratosis in the Korean males: Causative role of sunlight. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2003;19:73–80. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0781.2003.00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang RZ, Zhu WY. Seborrheic keratoses in five elderly patients: An appearance of raindrops and streams. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:432–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.84754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas VD, Swanson NA, Lee KK. Benign epithelial tumours, hamartomas and hyperplasias. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell D, editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012. pp. 1319–36. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engel A, Johnson ML, Haynes SG. Health effects of sunlight exposure in the United States. Results from the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1971-1974. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:72–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams MG. Acanthomata appearing after eczema. Br J Dermatol. 1956;68:268–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1956.tb12815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dantzig PI. Sign of Leser-Trélat. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:700–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foong HB, Ibrahimi OA, Elpern DJ, Tyring S, Rady P, Carlson JA. Multiple facial seborrheic keratosis-like lesions in a young woman with epidermodysplasia verruciformis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:476–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Senel E. Dermatoscopy of non-melanocytic skin tumors. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:16–21. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.74966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piccolo D, Smolle J, Argenziano G, Wolf IH, Braun R, Cerroni L, et al. Teledermoscopy – Results of a multicentre study on 43 pigmented skin lesions. J Telemed Telecare. 2000;6:132–7. doi: 10.1258/1357633001935202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soyer HP, Kenet RO, Wolf IH, Kenet BJ, Cerroni L. Clinicopathological correlation of pigmented skin lesions using dermoscopy. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:22–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nilles M, Boedeker RH, Schill WB. Surface microscopy of naevi and melanomas – Clues to melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130:349–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb02932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soyer HP, Smolle J, Hödl S, Pachernegg H, Kerl H. Surface microscopy. A new approach to the diagnosis of cutaneous pigmented tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 1989;11:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demirtasoglu M, Ilknur T, Lebe B, Kusku E, Akarsu S, Ozkan S. Evaluation of dermoscopic and histopathologic features and their correlations in pigmented basal cell carcinomas. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:916–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun RP, Rabinovitz HS, Krischer J, Kreusch J, Oliviero M, Naldi L, et al. Dermoscopy of pigmented seborrheic keratosis: A morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1556–60. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.12.1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elgart GW. Seborrheic keratoses, solar lentigines, and lichenoid keratoses. Dermatoscopic features and correlation to histology and clinical signs. Dermatol Clin. 2001;19:347–57. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70272-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]