Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common, chronic childhood skin disorder caused by complex genetic, immunological, and environmental interactions. It significantly impairs quality of life for both child and family. Treatment is complex and must be tailored to the individual taking into account personal, social, and emotional factors, as well as disease severity. This review covers the management of AD in children with topical treatments, focusing on: education and empowerment of patients and caregivers, avoidance of trigger factors, repair and maintenance of the skin barrier by correct use of emollients, control of inflammation with topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors, minimizing infection, and the use of bandages and body suits.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis, bandages, calcineurin inhibitors, compliance, education, emollients, empowerment, topical corticosteroids, topical therapy

Introduction

What was known?

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic childhood skin disorder and the treatment is complex

Topical treatment forms the mainstay of treatment for most of the patients.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common childhood skin disorder in developed countries, affecting 15%–20% of young children. It represents a complex interaction between susceptibility genes, immunological and neuroendocrine factors, skin barrier properties, and the environment. Most affected infants outgrow the condition by early childhood, but the course may be prolonged in those with early onset, severe, widespread disease, concomitant asthma or hay fever, and family history of AD. AD has a significant impact on well-being and quality of life for the whole family not just the patient. The itch of AD causes disturbed sleep, irritability, and psychological disturbance. There is no cure for AD, and hence the aims of management are control of inflammation, symptom improvement, and avoidance of complications. This review will focus on topical treatments for AD.

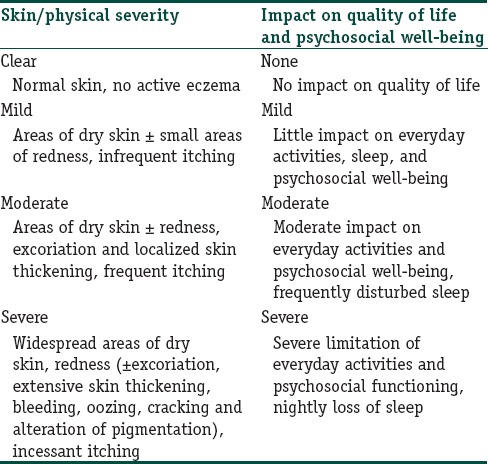

Assessment

Holistic assessment is essential to tailor treatment and monitor progress. A simple scheme is shown in Table 1,[1] but other scores include physician measures of severity such as SCORAD, EASI, and SASSAD[2] and patient measures such as Patient Orientated Eczema Measure.[3] Quality of life tools include CDLQI,[4] IDQOL,[5] and FDLQI.[6]

Table 1.

Holistic assessment, adapted from National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines[1]

Overview of Management

Treatment must be matched to disease severity, age of child, body site, climate, and lifestyle. Holistic management encompasses the following:

Education and empowerment of patients and caregivers

Avoidance of trigger factors

Repair and maintenance of skin barrier

Control of inflammation

Minimizing infection

Bandages and body suits.

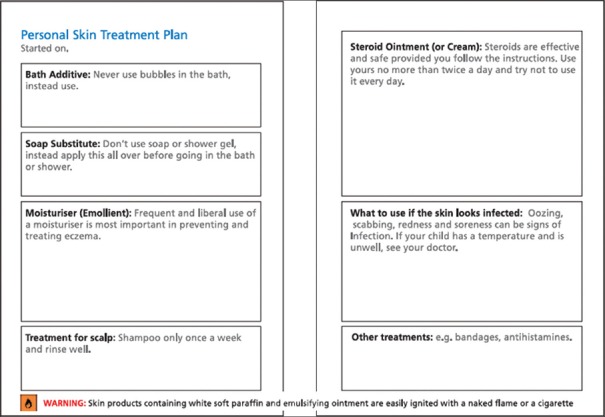

Education

There must be realistic expectations regarding outcomes: “control not cure.” Patients and carers should be taught to distinguish active eczema from dry skin and to recognize infection, as well as about maintenance of skin hydration, use of topical treatments, and avoiding triggers.[7] There is a lot to take in during a consultation: demonstration, teaching videos,[8] and written action plans [Figure 1] improve adherence. Psychological strategies to break the itch-scratch cycle may help. Nails should be kept short. Patients should be counseled about alternative remedies which may contain toxins.

Figure 1.

Template for written treatment plan

Trigger avoidance[7]

Many nonspecific factors can exacerbate AD: Infections, soaps, detergents, fragrances, rough or occlusive clothing, extremes of temperature, sweat, and psychosocial stress. There may be specific environmental allergens including house dust mite, and pets. These may be unavoidable, but exposure can be minimized. Specific additives in topical preparations can cause irritation or allergy.

Repair and maintenance of skin barrier

Bathing and washing[9]

A daily bath or shower removes scale, crust, irritants, and allergens and provides an opportunity to moisturize the skin. Water should be lukewarm, and 20 min immersion is adequate. Soaps, shampoos, and shower gels which lather should be avoided; they can irritate and dry the skin. Prepubertal children produce little sebum and require minimal shampoo. Bath oils may have a moisturizing effect, but evidence for efficacy is limited: Additives can irritate although lauromacrogols may have antipruritic properties. Neutral or low pH nonsoap cleansers that are hypoallergenic and fragrance free are available, but any moisturizer cream or lotion can be used as a soap substitute. It is easiest to apply the moisturizer before getting into the bath or shower, then massage it into the skin once in the water. Skin should be patted dry with a soft towel and emollient applied immediately. Bathroom surfaces can become dangerously slippery and should be rinsed thoroughly afterward with hot water.

Emollients are the main treatment for all grades of AD. The normally elastic and protective skin barrier is impaired in AD and emollients combat xerosis and transepidermal water loss. “Emollient” is used here as a blanket term covering lubricants (e.g., glycol, glyceryl stearate, and soy sterols) that soften the skin, occlusive agents (e.g., petrolatum, dimethicone, and mineral oil) that form a layer to retard evaporation of water, and humectants (e.g., urea, glycerol, and lactic acid) that attract and hold water.

Emollients are available in various formulations. Lotions are thin with a high water content and are useful for hairy areas and weeping eczema but ineffective for severe xerosis. Gels are similar to lotions, with high water content. Creams (emulsions of water and oil) are most popular: Easily rubbed in and do not leave a shine, but greasier than lotions and gels. Vegetable oils are popular in South Asia, for example, olive, almond, and mustard oil – the latter can be irritant. Some oils solidify in cold climates but soften at body temperature, for example, coconut oil. Ointments are thick and greasy and are suitable for very dry eczema; by contrast with lighter formulations, they lack preservatives which can sting. However, they are less cosmetically acceptable, can cause heat trapping and folliculitis, and can stain clothing and bedding. Additives which can cause irritation or allergy include preservatives such as parabens, keratolytics (urea), and antibiotics such as neomycin and antiseptics such as benzalkonium chloride and chlorhexidine. Added fragrance should be avoided. Concerns have been raised that sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), a surfactant found in many emollients (including aqueous cream), causes skin irritation, thinning of the stratum corneum, and increased transepidermal water loss, so SLS-containing emollients are used more as “wash-off” than “leave-on” emollients. Nonetheless, these compound preparations are useful and need not be discontinued unless the patient experiences a problem.

Patients should be encouraged to try different emollients, as well as being advised about the best type for their skin condition, climatic conditions, and lifestyle. Patients might use a gel- or cream-based emollient during the day and in hot weather, and an ointment at night time and in cold weather. The amount needed is often underestimated. Approximately 600 g/week is required for adults and 250 g/week for children with generalized eczema. Emollients should be applied as liberally and frequently as possible (up to 4 hourly), ideally when the skin is moist from a bath. They should be used all over and not just to the affected skin and smoothed onto the skin in the direction of the hair follicles to avoid folliculitis.

Control of inflammation

Patients must understand the difference between emollients to be applied frequently all over and anti-inflammatory agents to be used just on active eczema, not more than twice daily.

Topical corticosteroids[7,9,12,13,14]

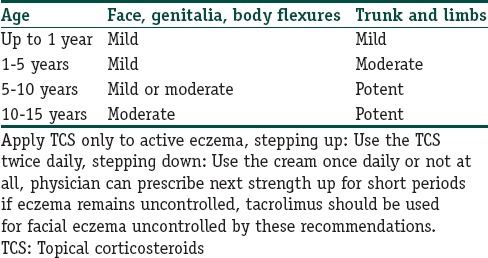

The evidence is well established for topical corticosteroids (TCS), which remain first-line anti-inflammatory therapy for active eczema despite their well-known adverse effects. Potential local adverse effects include infection, skin atrophy, telangiectasia, hypopigmentation, hypertrichosis, pustular eruptions, and eventually striae. The risk of these is higher for thinner skin (younger age, flexures, and face), high potency TCS, prolonged and continuous usage, and occlusion. Eyelids are particularly problematic because local absorption of TCS can cause cataract and glaucoma. Systemic absorption of TCS sufficient to cause adverse effects is rare but hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression, reduced linear growth in children, and reduced bone density in adults have been reported. Babies and children are at particular risk of absorption because of their high body surface area to weight ratio. Selecting the right TCS for a particular patient requires skill. First, available products differ in potency and formulation. Potency measured as vasoconstrictive effect is expressed in the UK as mild, moderate, potent, and very potent, and in the USA as class 1 (the most potent) to class 7 (least potent). Formulations vary as for emollients, see above, and also include mousse for scalp and steroid-impregnated tape for treating cracked palmoplantar skin and small localized areas of eczema. Second, the amount delivered is influenced by quantity and frequency of application and occlusion. Finally, patient factors must be considered, such as age, body site, and severity of eczema. Some patients are “steroid-happy” and will use excessive quantities, others are “steroid-phobic” and will use insufficient. Clearly, there are many more variables to consider than when prescribing oral medication.

Available guidelines on steroid usage advise different potencies according to severity, body site, and age. This is too complicated for many families, and the authors recommend a simple scheme using just two potencies [Table 2]. Patients and carers intuitively use more cream, more often, when and where the eczema is severe, and neglect to use it when and where the eczema is better. this seems to us a valid and pragmatic way of “stepping up and down.”

Table 2.

Simple scheme for choosing a topical corticosteroid

The “finger-tip unit” (FTU) is a useful concept in understanding quantities of TCS required. A line of cream, delivered from a standard 5 mm nozzle, from the distal interphalangeal joint to the tip of the index finger (1 FTU) equates to approximately 0.5 g and should cover an area equal to both palms. Absorption is better with moisturized skin. After a bath is ideal, but otherwise 20 min before or after applying emollient. Patients should be taught to apply the TCS to active, noninfected eczema, weaning down to emollient when the patch is controlled. With regards to frequency, TCS should be used once or twice daily. There is no evidence for higher efficacy with application more than twice daily. Patients who experience frequent, repeated outbreaks at the same body sites may benefit from the proactive application of TCS once to twice weekly at these locations even when the eczema is quiescent. This technique appears more effective than emollient alone in reducing rate of relapse and increasing time to first flare. Proactive once to twice weekly application of mid-potency TCS for up to 40 weeks has not shown any adverse event in clinical trials.

Combinations of TCS with antibiotics, antifungals, and antiseptics are popular. Disadvantages include overuse and resistance to antibiotics such as fusidic acid. Hypersensitivity can occur to such additives to preservatives and rarely to the steroid itself. The latter can be difficult to detect both clinically and on patch-testing because of the anti-inflammatory nature of TCS. False negative patch tests are common and an additional reading at 7–10 days is advised. About 90% of allergic contact dermatitis to TCS can be diagnosed by patch testing to tixocortol pivalate, budesonide, triamcinolone, and patient's own commercial steroid.

Topical calcineurin inhibitors[7,9,13,14,15,16]

TCIs are immunosuppressive agents which inhibit calcineurin in the skin, blocking early T-cell activation, and cytokine release. They are effective in reducing the inflammation of AD. In the UK, tacrolimus 0.03% ointment and pimecrolimus 1% cream are approved for use in children aged 2–15 years; tacrolimus 0.1% can be used >16 years.

TCIs are attractive alternatives to TCS because they do not cause atrophy, striae, or telangiectasia. They are particularly useful for areas where the skin is already thin such as face and flexures. Tacrolimus 0.1% is as effective as mid-potent TCS and more effective than mild TCS; tacrolimus 0.03% is less effective than betamethasone valerate 0.1%. Tacrolimus is more effective than pimecrolimus. However, TCIs may cause stinging, are relatively expensive, and have been suggested to increase cancer risk, based on the observation of increased malignancies in laboratory animals exposed to high doses of systemic calcineurin inhibitors and rare case reports of lymphoma and skin cancers in adult patients using TCIs. Patients using TCIs should therefore avoid additional risk factors for cancer such as excessive sun exposure. However, there is no significant systemic absorption and TCIs have been used in children for more than 15 years with no evidence of increased malignancy. TCIs may also be used proactively, once or twice weekly, to sites of repeated outbreaks of AD.

Other anti-inflammatory agents

The mast-cell stabilizing agent sodium cromoglycate showed greater improvement in SCORAD than vehicle alone[17] but is generally disappointing in practice. Other new topical agents include an extract of bacteria Rhodobacter sphaeroides, UR-1505, a small molecule with immune modulator properties,[18] and the thiol derivative N-acetylcysteine[19] but convincing evidence for efficacy in AD is so far lacking.

Minimizing infection[7,14]

Eczematous skin is prone to bacterial infections, particularly with staphylococcus and streptococcus, which may exacerbate or even drive AD. Topical treatment with antiseptics minimizes the risk of antibiotic resistance. Suitable agents include potassium permanganate solution, chlorhexidine, benzalkonium, mupirocin, and salt or bleach baths prepared by adding 120 ml (1/2 cup) of 6% household bleach to a full bathtub (40 gallons) of water. Persistent or recurrent staphylococcal infection may be due to nasal carriage by patient or family members which should be treated concurrently with nasal mupirocin[20] or chlorhexidine + neomycin cream. Significant infections require systemic antimicrobial therapy.

Atopic skin is also prone to viral infection, with herpes simplex and molluscum contagiosum, which can in turn exacerbate the eczema locally. Eczema herpeticum usually requires oral or intravenous treatment with acyclovir.

Although TCS and TCIs increase the risk of skin infection, they may paradoxically expedite resolution of infection by treating the eczematous environment in which microbes flourish. However, their use in infected skin should generally be avoided or covered with anti-infective agents.

Bandages and body-suits[9,11,21]

These may be used as an adjunct to standard topical treatments, especially emollients. They enhance penetration of topical agents, discourage scratching, and help to keep creams on the skin rather than on clothing, bedding, and furnishings. They may not be appropriate in a hot climate.

Lightweight tubular stretch bandages made of viscose or rayon with elastane, or silk, are readily available in a range of sizes to fit limbs and trunk at all ages. They can be tied or stitched to create leggings and sleeved vests, but manufacturers also produce ready-made garments from the same materials, without irritating seams and labels, which can be worn day and night, under clothing. Unlike pyjamas or commercial body-suits, they fit snugly to the body and limbs, retaining a constant environment next to the skin and minimizing irritation from temperature changes and friction. Although initially reluctant, most children with severe eczema find bandages and body-suits comforting. Bandage suits are usually changed twice daily to coincide with bathing and topical applications. They can be rolled back at other times to allow more cream to be applied. Some parents apply adhesive tape over the bandages at wrists and ankles to prevent children removing them. The most popular use of such bandages and body-suits is on top of standard treatment with emollient and TCS. This is sometimes known as “dry wrapping.”

“Wet wrap therapy” requires two layers: An inner layer which has been soaked in lukewarm water and wrung out, covered by a dry layer. Traditionally, this was used over a steroid + emollient cream applied all over, probably resulting in some systemic absorption of steroid. Wet wraps are now more commonly used over standard treatment with TCS applied to active eczema and emollient all over. Inevitably, the outer layer (and bedding) become wet, and the dressings dry out after a few hours although they can be refreshed using lukewarm water in an atomizer spray. Wet wrapping is sometimes helpful for an intractably itchy, insomniac child, but care must be taken to avoid chilling the child, exacerbating infection, and over-treating with steroid, since absorption is enhanced through moist occluded skin.

Paste bandages are impregnated with soothing agents such as zinc oxide and ichthammol. They can be applied to whole limbs or restricted to localized areas such as around joints, and can be left on for up to 24 h. They can be used over TCS. Dry bandages are needed on top since paste bandages are messy. Paste bandages must be applied with pleats to avoid constriction of the limbs as the bandage dries out and shrinks. As with wet wraps, hazards include infection and excessive penetration of TCS.

Conclusion

Management of AD is complex. The dermatologist must take into account geographical, climatic, cultural, lifestyle, and psychological factors. As with any chronic condition, expectations must be realistic. Education and empowerment of the patient and family are key.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

In the management of atopic dermatitis, treatment should be tailored to the individual

Disease severity, personal, social and emotional factors should be considered in deciding the treatment

Patient and family education forms an integral part of the management

Adequate education will help patients to use topical steroids in the right amount.

References

- 1.Atopic Eczema in Under 12s: Diagnosis and Management | Introduction | Guidance and Guidelines | NICE. [Last cited on 2016 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg57/chapter/introduction .

- 2.Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, Feldman SR, Hanifin JM, Simpson EL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charman CR, Venn AJ, Williams HC. The patient-oriented eczema measure: Development and initial validation of a new tool for measuring atopic eczema severity from the patients’ perspective. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1513–9. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.12.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olsen JR, Gallacher J, Finlay AY, Piguet V, Francis NA. Quality of life impact of childhood skin conditions measured using the children's dermatology life quality index (CDLQI): A meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2015;174:853–61. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basra MK, Gada V, Ungaro S, Finlay AY, Salek SM. Infants’ dermatitis quality of life index: A decade of experience of validation and clinical application. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:760–8. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basra MK, Edmunds O, Salek MS, Finlay AY. Measurement of family impact of skin disease: Further validation of the family dermatology life quality index (FDLQI) J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:813–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tollefson MM, Bruckner AL. Section on Dermatology. Atopic dermatitis: Skin-directed management. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e1735–44. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Information Video for Parents of Children with Eczema | Birmingham Children's Hospital. 2015. [Last cited on 2016 Feb 21]. Available from: http://www.bch.nhs.uk/story/information-video-parents-children-eczema .

- 9.Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, Krol A, Paller AS, Schwarzenberger K, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. [Last cited on 2016 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.pcds.org.uk/images/stories/pcdsbad-eczema.pdf .

- 11.Halpern DJ. A Practical Guide to Treating Eczema in Children. UK: Create Space Independent Publishing Platform; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Topical Steroids: National Eczema Society. [Last cited on 2016 Jan 24]. Available from: http://www.eczema.org/corticosteroids .

- 13.Schmitt J, von Kobyletzki L, Svensson A, Apfelbacher C. Efficacy and tolerability of proactive treatment with topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors for atopic eczema: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:415–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chong M, Fonacier L. Treatment of eczema: Corticosteroids and beyond. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s12016-015-8486-7. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sidbury R, Tom WL, Bergman JN, Cooper KD, Silverman RA, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Section 4. Prevention of disease flares and use of adjunctive therapies and approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1218–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCollum AD, Paik A, Eichenfield LF. The safety and efficacy of tacrolimus ointment in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:425–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stevens MT, Edwards AM. The effect of 4% sodium cromoglicate cutaneous emulsion compared to vehicle in atopic dermatitis in children – A meta-analysis of total SCORAD scores. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26:284–90. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2014.933766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Román J, de Arriba AF, Barrón S, Michelena P, Giral M, Merlos M, et al. UR-1505, a new salicylate, blocks T cell activation through nuclear factor of activated T cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:269–79. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.035212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakai K, Yoneda K, Murakami Y, Koura A, Maeda R, Tamai A, et al. Effects of topical N-acetylcysteine on skin hydration/transepidermal water loss in healthy volunteers and atopic dermatitis patients. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:450–1. doi: 10.5021/ad.2015.27.4.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sai N, Laurent C, Strale H, Denis O, Byl B. Efficacy of the decolonization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriers in clinical practice. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2015;4:56. doi: 10.1186/s13756-015-0096-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paste Bandages, Wraps and Therapeutic Garments: National Eczema Society. [Last cited on 2016 Jan 23]. Available from: http://www.eczema.org/products/107 .