Abstract

Importance

Sepsis survivors face long-term sequelae which diminish health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and result in increased care needs in the primary care setting as medication, physiotherapy or mental health care.

Objective

To examine if a primary care-based intervention improves mental HRQoL

Design, Setting and Participants

A randomized clinical trial was conducted between February 2011 and December 2014. 291 patients ≥18 years who survived sepsis (including septic shock) were recruited from nine intensive care units (ICU) across Germany.

Intervention

Participants were randomized to usual care (n=143) or to a 12-month intervention (n=148). Usual care was provided by their primary care physician (PCP) and included periodic contacts, referrals to specialists and prescription of medication and/or other treatment. The intervention additionally included PCP and patient training, case management provided by trained nurses and clinical decision support for PCPs by consulting physicians.

Main outcome

The primary outcome was change in mental HRQoL between ICU discharge and six months post-ICU using the Mental Component Summary (MCS) of the Short-Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36; range 0-100; higher ratings indicating lower impairment, minimal clinically important difference five score points).

Results

The mean age of the 291 patients was 61.6 years (SD 14.4), 66.2% (n=192) were male, and 84.4% (n=244) required mechanical ventilation during their ICU stay (median 12 days, range 0-134). At six and 12 months post-ICU, 75.3% (n=219, 112 intervention, 107 control) and 69.4% (n=202, 107 intervention, 95 control) completed follow-up, respectively. Overall mortality was 13.7% at six months (40 deaths, 21 intervention, 19 control) and 18.2% at 12 months (53 deaths, 27 intervention, 26 control). Among intervention group patients, 104 (70.3%) received the intervention at high levels of integrity. There was neither a significant difference in change of MCS scores (intervention group baseline, mean=49.1, six months=52.9, change=3.79 score points (95%CI 1.05; 6.54) vs. control group baseline, mean =49.3, six months=51.0, change=1.64 score points (95%CI -1.22; 4.51) mean treatment effect=2.15 (95%CI -1.79; 6.09); p=0.28), nor in PCP care delivered between both groups.

Conclusions and relevance

Among sepsis survivors, a primary-care-focused team-based intervention did not improve mental HRQoL or impact PCP care compared with usual care.

Trial Registration

ISRCTN registry; http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN61744782

Introduction

Sepsis is a major health problem worldwide.1 In 2008, it has been estimated to occur in 2% of hospitalized patients in the United States and is expected to rise further in the future, with an even higher incidence in developing countries.2 The risk of dying from sepsis has decreased in recent decades due to earlier detection and more effective treatment.3 Although more patients survive sepsis and are increasingly discharged from hospital4, they often experience functional disability, cognitive impairment and psychiatric morbidity5,6, resulting in diminished health-related quality of life (HRQoL)7, increased healthcare costs8,9 and burden on patients and their families.7,10

Many sepsis survivors have multiple medical comorbidities that are typically managed in primary care. Yet, interventions for managing sepsis sequelae in primary care have not been developed.5,11 A systematic review of outpatient interventions for patients surviving critical illnesses showed heterogeneous and small effects on clinical outcomes such as depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms.12 Studies with post-ICU follow-ups of six months or more are rare.7

The purpose of this randomized clinical trial was to assess whether a primary care-based intervention13 would improve mental-health-related quality of life among survivors of sepsis compared with usual care.

Methods

Study design and population

A multicenter, non-blinded, two-arm randomized clinical trial was performed. The institutional review board of the Jena University Hospital approved the study protocol (file 3001/111). All patients and primary care physicians (PCPs) in the study provided written informed consent. Serious adverse events were reported to a data and safety monitoring board. Patients were recruited in nine ICU study centers across Germany between February 2011 and December 2013. Follow-up assessments were completed in December 2014. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were adult (≥18 years old) survivors of severe sepsis, (now defined as ‘sepsis’14) or septic shock, and fluent in the German language. Clinical diagnoses on sepsis were made by intensivists according to International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) codes (R65.1/R57.2) and ACCP/SCCM consensus criteria.15 Baseline interviews of patients were conducted by the study team within one month of ICU discharge. Key exclusion criteria was cognitive impairment, as determined by the Telephone Interview of Cognitive Status (TICS-M, score≤27).16 After determining patient eligibility, the study team invited each patient's PCP to participate in the trial.

Randomization was stratified by ICU study centers and performed using computer-generated random permutated blocks (block size range 2-6), provided by an independent center for clinical trials at the University of Leipzig.

Intervention

The intervention was based on the Chronic Care Model17. Its core components included case management focusing on pro-active patient symptom monitoring, clinical decision support for the PCP and training for both patients and their PCPs in evidence-based care. Three nurses with ICU experience were trained as outpatient case managers of sepsis survivors in an eight hour workshop. The training included information on sepsis sequelae, communication skills, telephone monitoring and behavioral activation of patients that included goal-setting (‘sepsis case manager manual’, Supplement). Each case manager worked with 38-65 patients, starting with a 60-minute face-to-face training on sepsis sequelae (‘sepsis help book’, Supplement) that took place a median of eight days after ICU discharge [Q1=2; Q3=20]. This was followed by monthly telephone contact for six months, then once every three months for the final six months. Case managers monitored patients' symptoms using validated screening tools (‘sepsis-monitoring-checklist’, Supplement) on critical illness polyneuropathy/myopathy, wasting, neurocognitive deficits, PTSD, depressive and pain symptoms, as well as patient self-management behaviors focusing on physical activity and individual self-management goals. Each case manager reported results to one of three assigned consulting physicians (medical doctors with background in primary and critical care), who supervised the case managers and provided clinical decision support to the PCPs using a structured written report which included the ‘sepsis-monitoring checklist’ (Supplement, eFigure 3). The reports were stratified by urgency using a traffic light scheme: red signified “immediate intervention recommended”, yellow “intervention should be considered” and green “acceptable clinical status.” An evidence-based sepsis aftercare training for the patients' PCPs was provided individual, in-person by the consulting physicians (‘sepsis PCP manual’, Supplement). Intervention delivery was considered to have high integrity if the training was delivered to both patients and PCPs and the patient was monitored five or more times.

Control group patients received care as usual from their PCPs without additional information or monitoring. Usual sepsis aftercare included periodic contacts, referrals to specialists and prescription of medication and therapeutic aids, at quantities comparable to those for other populations with multiple chronic conditions18. In Germany most primary care practices are privately operated by one or two PCPs with limited access to specialist care.19 There are no outpatient post-sepsis/ICU follow-up clinics or national treatment guidelines for sepsis aftercare in Germany.

Baseline data and outcomes

Baseline data were collected at in-person interviews with patients while they were still hospitalized. Further clinical data were obtained from their ICU records. Since the majority of patients remained hospitalized and incapacitated, baseline data collection of Activities of Daily Living (ADL), physical function and insomnia was not feasible.

The primary outcome was change in mental HRQoL between ICU discharge and six months post-ICU, as assessed by the Mental Component Summary score (MCS) of the Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36, range 0-100 with higher ratings indicating low impairment20(+). The SF-36 consists of eight sub-scores and is valid and reliable in both post-ICU21 and German primary care populations.22

Secondary outcomes at six months were derived from (1) the other SF-36 scales (range 0-100(+); (2) overall survival; (3) mental health outcomes including the Major Depression Inventory (MDI, range 0-50, high scores indicate high impairment(-)23), the Post-Traumatic Symptom Scale (PTSS-10, range 10-70(-)24), the TICS-M (range 0-50(-)16; (4) functional outcomes including ADL (range 0-11(+)25, the Extra Short Musculoskeletal Function Assessment regarding physical function and disability (XSMFA-F/B, range both 0-100(-)26, the Graded Chronic Pain Scale including a Disability Score and Pain Intensity (GCPS-DS/PI, range 0-100(-)27, the Neuropathy Symptom Score (NSS, range 0-10(-)28, the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST, range 0,-2(-)60) including the Body Mass Index (BMI)61 and the Regensburg Insomnia Scale (RIS, range 0-40(-).29

Process-related outcomes (5) included the Patient Assessment of Care for Chronic Conditions (PACIC, (0-10(+)30,31 and measures of medication adherence, the modified Morisky questionnaire (range 1-5(-)32 and the Short Form for Medication Use (KFM, range 0-12(-).33 In addition, process-related data from PCP documentation (6) were derived, including PCP contacts (no.), referrals to specialists (no.), level of nursing, inability to work (days), remedies and therapeutic aids (no.) and LOS in hospital and rehabilitation clinic (days). All 31 secondary outcomes pre-specified in the statistical analysis plan (SAP) (see Supplement) are reported in the Supplement (eTable 2-8).

In addition, we also included as secondary outcomes all of the above measured at 12 months post-ICU. Outcome assessment was conducted by non-blinded assessors by phone.

Initially, the MCS as well as the Physical Component Summary score (PCS) of the SF-36 were chosen for primary outcome to provide a multicomponent score reflecting HRQoL (as noted in the study protocol13 and the ISRCTN registration). However, based on review of the literature12 highlighting the importance of mental health outcomes in post-ICU care, the primary outcome was specified to the MCS.

Statistical analysis

The aim of the study was to detect a difference at six months of five points or more in mean MCS scores since this amount of change is thought to be clinically meaningful.22 A common standard deviation of 10 was assumed on the basis of a typical German population with acute and chronic diseases.34 At a two-sided significance levelα = 0.05, a total of 2×86=172 patients were required to detect the above mentioned effect with a power of 90%. Allowing for an additional ∼40% for drop-outs and mortality, an initial sample size of 287 was required. The confirmatory test for the primary outcome was Welch's t-test for independent groups which was run in the intention-to-treat population. The confirmatory analyses did not consider intra-practice clustering because n=155 (96.9%) of intervention practices and n=141 (95.1%) of control practices included only one patient. The effect clustering and missing values were explored by e.g. linear mixed models and imputations. Details on methods and results of exploratory sensitivity analyses are provided in the Supplement (eMethods). All secondary outcome analyses were exploratory and not adjusted for multiple tests. They were done using the t-test, Fisher's exact test and the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, as appropriate. Overall survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method with study groups compared using the log-rank test. A confirmatory and exploratory two-sided significance level of α=0.05 was applied, and effect size estimates with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were reported. All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 3.2.3).35

Results

Baseline Characteristics

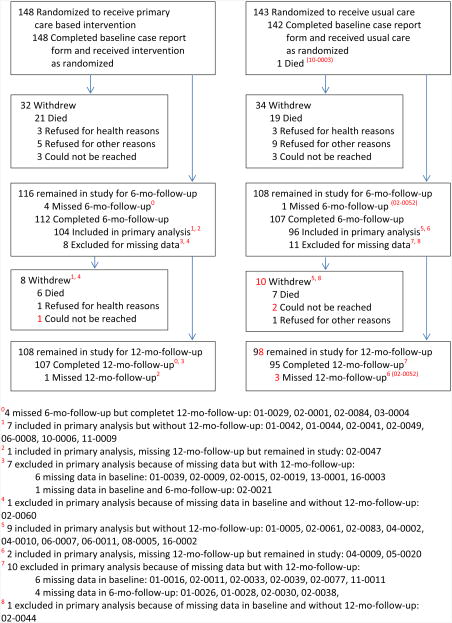

A total of 361 patients were eligible, of which 291 (80.6%) agreed to participate, with 148 patients randomized to the intervention and 143 patients to the control group (Figure 1). Overall, baseline characteristics were well balanced (Table 1). The mean age of the cohort was 61.6 years (standard deviation (SD) 14.4), 244 patients (84.4%) received mechanical ventilation, the median ICU LOS was 26 days [Q1=13, Q3=46]. Mental HRQoL was close to the normal population (mean MCS 49.0, SD 12.5), physical HRQoL was low (mean SF-36 (PCS) 25.3,SD 8.8). 24.2%. (68 of 281) had substantial depressive symptoms, 14.6% (41 of 281) reported substantial PTSD symptoms and 19.6% (54 of 276) indicated severe pain (Table 1). Among the entire cohort, 59.2% (164 of available 277) reported neuropathic symptoms.

Figure 1. CONSORT flow diagram of patient recruitment and retention rates during the study course.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

| Characteristics | All (n = 290) |

Intervention (n = 148) |

Control (n = 142) |

NA (i; c) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 61.6 (14.4) | 62.1 (14.1) | 61.2 (14.9) | 0; 0 |

|

| ||||

| Sex “Male”, No. (%) | 192 (66.2) | 105 (70.9) | 87 (61.3) | 0; 0 |

|

| ||||

| Family status “Married”, No. (%) | 148 (52.1) | 84 (57.9) | 64 (46.0) | 3; 3 |

|

| ||||

| Educational status “< High school”, No. (%) | 98 (34.0) | 54 (36.7) | 44 (31.1) | 1; 1 |

|

| ||||

| Care measures | ||||

| Recent surgical history, No. (%) | 2; 1 | |||

| Emergency | 106 (36.8) | 49 (33.6) | 57 (40.1) | |

|

| ||||

| Elective surgery | 62 (21.5) | 34 (23.3) | 28 (19.7) | |

|

| ||||

| No history | 73 (25.3) | 39 (26.7) | 34 (23.9) | |

|

| ||||

| Source of infection, No. (%) | 3; 5 | |||

| Community acquired | 102 (36.0) | 54 (37.2) | 48 (34.8) | |

|

| ||||

| Nosocomial (ICU or IMC) | 139 (49.1) | 70 (48.3) | 69 (50.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Nosocomial (general ward or nursing home) | 42 (14.8) | 21 (14.5) | 21 (15.2) | |

|

| ||||

| ICU length of stay days: median, mean (SD) [Q1;Q3] | 26, 34.4 (27.2) [4; 27] | 23, 31.5 (27.7) [4; 26] | 29, 35.2 (26.7) [5; 28] | 16; 11 |

|

| ||||

| Mech. ventilation, No. (%) | 244 (84.4) | 121 (82.3) | 123 (86.6) | 1; 1 |

|

| ||||

| if applicable, days: median, mean (SD) [Q1;Q3] | 12, 18.5 (19.2) [4; 27] | 10, 17.0 (17.5) [4; 26] | 14, 19.9 (20.7) [5; 28] | 5; 4 |

|

| ||||

| Renal replacement therapy, No. (%) | 82 (28.5) | 43 (29.3) | 39 (27.7) | 1; 2 |

|

| ||||

| if applicable, days: median, mean (SD)[Q1;Q3] | 8, 12.3 (13.2) [4; 15] | 7, 11.9 (13.7) [4; 14] | 8, 12.8 (12.8) [5; 16] | 5; 5 |

|

| ||||

| Clinical Measures | ||||

| Comorbidity: Charlson Indexa1, mean (SD) | 4.0 (2.9) | 4.0 (3.0) | 4.0 (2.9) | 1; 1 |

|

| ||||

| ICD-diagnoses, No., median, mean (SD) | 9, 10.1 (4.7) | 9, 9.6 (4.4) | 10, 10.6 (5.1) | 6; 7 |

|

| ||||

| BMIb12, mean (SD) | 27.3 (6.0) | 27.3 (6.0) | 27.3 (5.9) | 3; 9 |

|

| ||||

| Depression | 3; 6 | |||

| MDIc1, mean (SD) | 18.1 (10.0) | 18.4 (9.8) | 17.8 (10.1) | |

|

| ||||

| Depressive symptoms, No. (%) | 68 (24.2) | 36 (24.8) | 32 (23.5) | |

|

| ||||

| PTSD | 3; 6 | |||

| PTSS-10d1, mean (SD) | 23.6 (10.4) | 24.0 (11.0) | 23.2 (9.7) | |

|

| ||||

| Score >35, No. (%) | 41 (14.6) | 22 (15.2) | 19 (14.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Cognition: TICS-Mcg2, mean (SD) | 33.4 (3.6) | 33.7 (3.4) | 33.1 (3.9) | 1; 0 |

|

| ||||

| Neuropathic symptoms | 4; 9 | |||

| NSSe1 mean (SD) | 3.6 (3.2) | 3.6 (3.3) | 3.7 (3.1) | |

|

| ||||

| Score 3-10, No. (%) | 164 (59.2) | 83 (57.6) | 81 (60.9) | |

|

| ||||

| Pain | ||||

|

| ||||

| Intensity: GCPS PIf1 mean (SD) | 43.8 (24.4) | 43.7 (25.6) | 43.9 (23.1) | 5; 9 |

|

| ||||

| Disability: GCPS DSf2 mean (SD) | 36.2 (34.6) | 36.0 (34.5) | 36.4 (34.8) | 7; 12 |

|

| ||||

| Severe pain: GCPS cat. >1, No. (%) | 54 (19.6) | 26 (18.2) | 28 (21.0) | 5; 9 |

|

| ||||

| Quality-of-Life Measures | ||||

| HRQoL | 12; 15 | |||

| SF-36 MCS f2, mean (SD) | 49.0 (12.5) | 48.8 (12.5) | 49.2 (12.6) | |

|

| ||||

| SF-36 PCS f2, mean (SD) | 25.3 (8.8) | 25.9 (9.4) | 24.7 (8.0) | |

Abbreviations: BMI, Body Mass Index; GCPS DS, Graded Chronic Pain Scale Disability Score; GCPS PI, Graded Chronic Pain Scale Pain Intensity; HRQoL, Health Related Quality Of Life; ICU, intensive care unit; IMC, Intermediate Care; MDI, Major Depression Inventory; NA (i; c), Not Available (intervention; control); NSS, Neuropathic Symptom Score; PTSD, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder; PTSS, Post-Traumatic Symptom Scale; SF-36 MCS, Short Form (36) Health Survey Mental Component Score; SF-36 PCS, Short Form (36) Health Survey Physical Component Score; TICS-M, modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status; NA, not available; i, intervention; c, control

Anchors:

high score indicates high impairment,

high score indicates low impairment

Ranges:

The range of possible scores is 0-37,

The range of possible scores is 9-46,

The range of possible scores is 0-50,

The range of possible scores is 10-70,

The range of possible scores is 0-10,

The range of possible scores is 0-100

values only above 27 (inclusion criteria)

Follow up

All included 291 patients were cared for by 159 intervention PCPs and 148 control PCPs. Due to some patient-initiated PCP changes, the number of PCPs was slightly larger than the number of patients (details see Supplement, eMethods). Among the 307 assigned PCPs, N=294 (95.8%) were willing to participate. Loss to follow-up due to withdrawal or non-response totaled 31 patients (10.7%) at six months and an additional nine patients (3.1%) at 12 months post-ICU, and was evenly distributed across study groups, see Figure 1.

Intervention delivery

Of the 148 patients assigned to the intervention, 130 (87.8%) received patient training from case managers and 125 (84.5%) of their PCPs received training from a consulting physician. There was a mean gap of 62.38 days [Q1=36, Q3=99] between ICU discharge and PCP training, caused by the wide range of patient clinical courses. 104 (70.3%) patients in the intervention group received the planned intervention at high levels of intervention integrity (see Supplement, eFigure2). Incomplete intervention was usually due to death of the patient (n=24 (54%) of those with less than five monitoring calls). Reduction of motoric function (n=204, 27.1%) and pain intensity (n=201, 27.2%) were the post-sepsis symptoms most rated “red” (=“immediate intervention recommended”) in all 756 structured monitoring reports (see Supplement, eTables 10).

No adverse events related to the intervention were reported.

Primary outcome

There was no significant difference between both groups in the primary outcome: The mean change MCS score was 3.79 score points (95%CI, 1.05; 6.54) for the intervention and 1.64 score points (95%CI, 1.22; 4.51) for the control group, leading to a mean treatment effect of 2.15 (95%CI -1.79; 6.09); p=0.28; baseline, mean=49.1 intervention vs. 49.3 control; six months, mean=52.9 intervention vs. 51.0 control (all data related to n=200 patients (n=104 intervention, n=96 control) with both MCS scores available at baseline and six months; due to rounding, change scores presented may not add up precisely). These results were unchanged in several sensitivity analyses (Supplement, eTable 1).

Secondary outcomes

A total of 63 secondary outcomes were analyzed at both six and 12 months (including the 12-month MCS). A respective 28 (six month) and 30 (12 month) outcomes did not show significant differences (at an uncorrected α=0.05) between both groups, including physical HRQoL and mental health outcomes (Supplement, eTables 2-3). Overall mortality at six and 12 months post-ICU was n=40 (13.7%) and n=53 (18.2%), respectively (Supplement, eFigure1). If any, potential intervention effects were observed in measures of functional outcomes only: At the six months, sepsis survivors receiving the intervention had better physical functioning (XSFMA-F, mean (95%CI), 38.0 (32.5; 43.5) vs.46.9 (40.9; 52.9); p=0.04, difference (95%CI) -8.9 (-17.02;-0.78), less physical disability (XSFMA-B,, 42.5 (36.6; 48.4) vs. 52.4 (46.2; 58.7); p=0.03, difference (95%CI) -9.9 (-18,49;-1.31) and fewer ADL impairments, mean (95%CI), 8.6 (8.0; 9.1) vs. 7.6 (7.0; 8.2);p=0.03; difference (95%CI) 1.0 (0.16;1.84) than usual care. After adjusting for pre-specified baseline covariates, these potential effects were persistent. In addition, sepsis survivors receiving the intervention had potentially fewer sleep impairments at 12 months post-ICU than controls (RIS, mean (95%CI), 10.3 (9.2; 11.4) vs. 12.1 (10.8; 13.4); difference (95%CI) -1.8 (-3.5;-0.10).

Finally, the PCP documentation data at six and 12 months provided no evidence for group differences in PCP care (Supplement, eTable 8).

Discussion

Among sepsis survivors, a primary-care-based intervention, compared with usual care, did not improve mental HRQoL.

To our knowledge, this is the first large scale, randomized controlled clinical trial of an intervention to improve outcomes in sepsis survivors in primary care.

This sample of sepsis survivors had similar mean ages and rates of existing comorbidities as compared to other cohorts.36,37 The prevalence of depressive and PTSD symptoms was slightly below other critical illness survivor populations,38,39 whereas neuropathic symptoms and severe pain were more frequent.40,41 Physical function, as measured by the SF-36 PF, was substantially lower than in the German population (mean 85.71 (SD 22.1), n=2886)34, and also lower than in some comparable cohorts42,43 and intervention studies.44,45 Thus, patients may have been more sensitive to the intervention's focus on increasing motivation to be physically active.

Study patients were exposed to longer durations of mechanical ventilation and ICU LOS than reported in other studies.4 ICU LOS and duration of mechanical ventilation were shown to generally be longer in Europe than in the US, especially in sepsis survivors.46,47 In addition, extensive ICU LOS may have facilitated patient identification by the intensivists.

There was no evidence for a differential treatment effect on the study's primary outcome, post-sepsis MCS scores. This finding is similar to previous trials of care management interventions following critical illness12,44,45,48. The absence of an intervention effect on the primary and most secondary outcomes can be considered along the PICO frameworks:49

Population

The studied cohort experienced heterogeneous clinical multiple conditions. This primary-care based intervention may not have been sufficiently focused in order to address all their diverse medical and psychological needs.50 Future trials may evaluate interventions in different patient subgroups targeting specific post-sepsis sequelae. Larger samples should be included, in order to address smaller but potentially still clinically relevant effects of primary care interventions.

Intervention

The exploratory analyses indicated no intervention effects on mental health symptoms. These results may reflect lack of intervention intensity and specificity, or absence of clinically effective interventions. However, there is growing evidence that following critical illness, mental health outcomes can be improved through effective psychological interventions targeting specific syndromes.50,51

Controls

According to process data derived from control PCPs (Supplement, eTable 8), usual sepsis aftercare in Germany seems to be highly intensive. PCP training and consultation may have been insufficient to yield a meaningful improvement in the level of care. Observational research may provide more insights in existing usual sepsis aftercare in diverse health care systems.

Outcome

The wide range of post-sepsis sequelae may not be adequately reflected in a rather global outcome measure change such as the SF-36 MCS. Furthermore, cohort's baseline mental HRQoL was similar to healthy population norms in Germany, reflecting a limited potential for improvement in the MCS. Finally, the exclusion of patients with more severe cognitive dysfunction may have led to a ceiling effect compared to other trials. For future trials, more specific primary outcomes should be considered.

Up to years after the ICU discharge many patients seem to share their needs with a reliable medical professional52. Yet the PCP isn't involved systematically in post ICU care.53,54 This study may shed light on the PCP relevance, addressing major concerns recently identified as “barriers to practice.”55 These include checks on transition from ICU through to community reintegration, linkage and clinical decision support to primary care, inclusion of a case manager and educational information for patients and PCPs. Compared to the large scale PRaCTICAL trial on follow-up care in ICU-clinics45 this study defines a clear function for the PCP in sepsis aftercare. Follow-up care combining specialized ICU-clinics and integrated PCP may improve outcomes.

This study's exploratory findings suggest possible improvements of physical function and ADL impairments. Additional research is needed to confirm these results. Possible mechanisms of action for these findings may include increased patient motivation (despite of the presence of pain) to partake in physical activity due to regular case manager phone calls with goal-setting and basic behavioral activation. Increased PCP supportiveness in the intervention group may also have motivated patients to be more pro-active, possibly reflected by the increased rating in number of PACIC items (Supplement, eTable 9).

This study has strengths and limitations. It was possible to enroll a large number of patients in spite of the challenges of recruiting critically ill patients for research.56 Intervention integrity went as planned57 (Supplement, eFigure 2), including the acceptance of an external medical consultant by the patient's PCP. These findings are encouraging for further interventions in the primary care setting.

Loss to follow-up was balanced between the groups and low, in contrast to sample size calculations which allowed for 40% drop out. Baseline values were missing for some secondary outcomes due to patient's severely impaired clinical condition. A carry-over effect (from treatment to control) may have occurred for one PCP inducing a bias toward a null effect. Calling control patients to collect follow-up data may have led to an intervention effect possibly leading to underestimation of the intervention effects.58. In addition, non-blinded outcome assessments may also have biased the results.59 The intervention is not generalizable to all sepsis survivors seen in various outpatient settings.

Conclusions

Among survivors of sepsis or septic shock, the use of a primary-care-focused team-based intervention, compared with usual care, did not improve mental HrQoL and did not change PCP care. Further research is needed to determine if other approaches to primary care management may be more effective to improve mental HQoL in sepsis survivors.

Supplementary Material

eFigure 1: Secondary outcome analysis of overall survival

eFigure 2: Venn diagram on intervention delivery

eFigure 3: Network and functioning of intervention actors

eTable 1: Primary outcome confirmatory test and sensitivity analyses

eTable 2: Secondary outcomes analysis of all SF-36 scales

eTable 3: Secondary outcomes analysis of measures of mental health

eTable 4: Secondary outcomes analysis of functional measures

eTable 5: Secondary outcomes analysis of patient reported process-related measures

eTable 6: Baseline data (at ICU discharge) on secondary outcome measures

eTable 7: Clinical significance on secondary outcome scales

eTable 8: Secondary outcomes analysis of process-related measures derived from PCP

eTable 9: Item analysis of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care questionnaire (PACIC)

eTable 10a: Topics of all Monitoring calls stratified by clinical urgency

eTable 10b: Monitoring stratification on patient level

Key Points.

Question

Does a primary care-based management intervention improve mental health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in sepsis survivors?

Findings

A randomized clinical trial was performed with 291 patients for 12 month. The intervention did not improve mental HRQoL.

Meaning

Future research is needed to improve mental HRQL in sepsis survivors.

Acknowledgments

Sponsorship/Financial Support: The study was supported by the Center of Sepsis Control & Care (CSCC), funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) [grant 01 E0 1002) and the German Sepsis Society (GSS); Dr. Brunkhorst: Thuringian Ministry of Education, Science and Culture [grant PE 108- 2]; Thuringian Foundation for Technology, Innovation and Research (STIFT); Dr. Davydow: National Institutes of Health [grant KL2 TR000421]. Dr. Gensichen: The Primary Health Care Foundation, Jena/Frankfurt, Germany. The funding organizations are public institutions and had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, and analysis of the data; or preparation, review, approval of the manuscript and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr. Schmidt and Dr. Gensichen had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Schmidt, Ehlert, Brunkhorst, von Korff, Gensichen.

Acquisition of Data: Schmidt, Worrack, Mehlhorn, Gensichen.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Schmidt, Worrack, Ehlert, Pausch, Davydow, Wensing, Scherag, Mehlhorn, von Korff, Brunkhorst, Schneider, Gensichen.

Drafting of the manuscript: Schmidt, Davydow, Wensing, von Korff, Scherag, Gensichen.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Schmidt, Davydow, Pausch, Mehlhorn, von Korff, Brunkhorst, Freytag, Wensing, Scherag, Schneider, Gensichen.

Statistical analyses: Pausch, Scherag, Schmidt, Worrack, Schneider, Gensichen.

Obtained funding: Reinhart, Gensichen.

Study supervision: Schmidt, Gensichen, Ehlert, Brunkhorst, Wensing, von Korff.

Competing interest statement: All authors declare that they have no competing interest and therefore have nothing to declare.

SMOOTH-study group: The authors and Anne Bindara-Klippel, Carolin Fleischmann MD, Ursula Jakobi MD, Susan Kerth, Heike Kuhnsch, Friederike Mueller MD, Mercedes Schelle, Paul Thiel MD, Institute of General Practice and Family Medicine, Jena University Hospital; Mareike Baenfer, Sabine Gehrke-Beck MD, Christoph Heintze MD, Charité University Medicine Berlin, Andrea Geist, Torsten Schreiber MD, Zentralklinik Bad Berka;Christian Berhold MD, Marcel Corea MD, Adrian Freytag MD, Herwig Gerlach MD MBA, Rainer Kuehnemund MD, Josefa Lehmke MD, Peter Lehmkuhl MD, Lorenz Reil MD, Guenter Tiedemann MD, Susanne Toissaint MD, Siegfried Veit MD, Vivantes Clinics Berlin; Anton Goldmann MD, Michael Oppert MD, Didier Keh MD, Sybille Rademacher MD, Claudia Spies MD, Lars Toepfer MD, Charite University Medicine Berlin; Frank Klefisch MD, Paulinen Hospital Berlin; Ute Rohr MD, Hartmut Kern MD, DRK Clinics Berlin; Armin Sablotzki MD, St. Georgs Hospital Leipzig; Frank Oehmichen MD, Marcus Pohl MD, Bavaria Clinic Kreischa; Andreas Meier-Hellmann MD, Helios Clinic Erfurt; Farsin Hamzei MD, Moritz-Clinic Bad Klosterlausnitz; Christoph Engel MD, Institute for Medical Informatics, Statistics and Epidemiology, University of Leipzig; Michael Hartmann MBA MPH, Christiane Hartog MD, Jena University Hospital; Jürgen Graf MD, Clinic Stuttgart; Günter Ollenschlaeger MD PhD, ÄZQ Berlin; Gustav Schelling MD, University Clinic LMU Munich.

References

- 1.Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(21):2063. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1312359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall MJ, Williams SN, DeFrances CJ, Golosinskiy A. Inpatient care for septicemia or sepsis: a challenge for patients and hospitals. NCHS data brief. 2011(62):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwashyna TJ, Angus DC. Declining case fatality rates for severe sepsis: good data bring good news with ambiguous implications. JAMA. 2014;311(13):1295–1297. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Suzuki S, Pilcher D, Bellomo R. Mortality related to severe sepsis and septic shock among critically ill patients in Australia and New Zealand, 2000-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(13):1308–1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304(16):1787–1794. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davydow DS, Hough CL, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ. Symptoms of depression in survivors of severe sepsis: a prospective cohort study of older Americans. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(9):887–897. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winters BD, Eberlein M, Leung J, Needham DM, Pronovost PJ, Sevransky JE. Long-term mortality and quality of life in sepsis: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(5):1276–1283. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181d8cc1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodwin AJ, Rice DA, Simpson KN, Ford DW. Frequency, cost, and risk factors of readmissions among severe sepsis survivors. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(4):738–746. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prescott HC, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ. Readmission diagnoses after hospitalization for severe sepsis and other acute medical conditions. JAMA. 2015;313(10):1055–1057. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee H, Doig CJ, Ghali WA, Donaldson C, Johnson D, Manns B. Detailed cost analysis of care for survivors of severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(4):981–985. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000120053.98734.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGovern M, McGovern C, Parker R. Survivors of critical illness: victims of our success? Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61(593):714–715. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X612945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehlhorn J, Freytag A, Schmidt K, et al. Rehabilitation interventions for post intensive care syndrome. A systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(5):1263–1271. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt K, Thiel P, Mueller F, et al. Sepsis survivors monitoring and coordination in outpatient health care (SMOOTH): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15(1):283. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101(6):1644–1655. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Jager CA, Budge MM, Clarke R. Utility of TICS-M for the assessment of cognitive function in older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18(4):318–324. doi: 10.1002/gps.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner EH, Austin BT, von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van den Bussche H, Schön G, Kolonko T, et al. Patterns of ambulatory medical care utilization in elderly patients with special reference to chronic diseases and multimorbidity--results from a claims data based observational study in Germany. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-11-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zentralinstitut für die kassenärztliche Versorgung in Deutschland. [Accessed March 24, 2015];ZI-Praxis-Panel: Jahresbericht 2012 - Wirtschaftliche Situation und Rahmenbedingungen in der vertragsärztlichen Versorgung der Jahre 2008 bis 2010. https://www.zi-pp.de/pdf/ZiPP_Jahresbericht_2012.pdf.

- 20.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M. SF-36 Version 2 health survey: manual and interpretation guide. Lincoln: Quality Metric Incorporated; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chrispin PS, Scotton H, Rogers J, Lloyd D, Ridley SA. Short Form 36 in the intensive care unit: assessment of acceptability, reliability and validity of the questionnaire. Anaesthesia. 1997;52(1):15–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1997.015-az014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bullinger M. German translation and psychometric testing of the SF-36 Health Survey: preliminary results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(10):1359–1366. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00115-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuijpers P, Dekker J, Noteboom A, Smits N, Peen J. Sensitivity and specificity of the Major Depression Inventory in outpatients. BMC psychiatry. 2007;7:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoll C, Kapfhammer HP, Rothenhausler HB, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of a screening test to document traumatic experiences and to diagnose post-traumatic stress disorder in ARDS patients after intensive care treatment. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25(7):697–704. doi: 10.1007/s001340050932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fonda S, Herzog AR. HRS/AHEAD documentation report Documentation of physical functioning measured in the heath and retirement study and the asset and health dynamics among the oldest old study. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center University of Michigan; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wollmerstedt N, Kirschner S, Bohm D, Faller H, Konig A. Design and evaluation of the Extra Short Musculoskeletal Function Assessment Questionnaire XSMFA-D. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 2003;141(6):718–724. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-812406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain. 1992;50(2):133–149. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haslbeck M, Luft D, Neundörfer B, Stracke H, Hollenrieder V, Bierwirth R. Diabetische Neuropathie. Diabetologie. 2007;2(Suppl. 2):150–156. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cronlein T, Langguth B, Popp R, et al. Regensburg Insomnia Scale (RIS): a new short rating scale for the assessment of psychological symptoms and sleep in insomnia; study design: development and validation of a new short self-rating scale in a sample of 218 patients suffering from insomnia and 94 healthy controls. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:65. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-11-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosemann T, Laux G, Droesemeyer S, Gensichen J, Szecsenyi J. Evaluation of a culturally adapted German version of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC 5A) questionnaire in a sample of osteoarthritis patients. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13(5):806–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glasgow RE, Wagner EH, Schaefer J, Mahoney LD, Reid RJ, Greene SM. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) Med Care. 2005;43(5):436–444. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000160375.47920.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24(1):67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watzl H, Rist S, Höcker W, Miehle K. Entwicklung eines Fragebogens zum Medikamentenmiβbrauch bei Suchtpatienten. In: Heide N, Lieb H, editors. Sucht und Psychosomatik. Bonn: Fachverbandes Sucht e.V.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bullinger M, Kirchberger I. SF36 Fragebogen zum Gesundheitszustand Handanweisungen. Göttingen, Bern, Toronto, Seattle: Hogrefe Verlag für Psychologie; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 35.R Core Team. [Accessed May 21, 2015];R: A language and environment for statistical computing. http://www.r-project.org/

- 36.Karlsson S, Varpula M, Ruokonen E, et al. Incidence, treatment, and outcome of severe sepsis in ICU-treated adults in Finland: the Finnsepsis study. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(3):435–443. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0504-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hofhuis JG, Spronk PE, van Stel HF, Schrijvers AJ, Rommes JH, Bakker J. The impact of severe sepsis on health-related quality of life: a long-term follow-up study. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2008;107(6):1957–1964. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318187bbd8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davydow DS, Zatzick D, Hough CL, Katon WJ. A longitudinal investigation of posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms over the course of the year following medical-surgical intensive care unit admission. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(3):226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parker AM, Sricharoenchai T, Raparla S, Schneck KW, Bienvenu OJ, Needham DM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(5):1121–1129. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marx G, Zimmer A, Rothaug J, Mescha S, Reinhart K, Meissner W. Chronic pain after surviving sepsis. Crit Care. 2006;10(Suppl 1):421. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Griffiths J, Fortune G, Barber V, Young JD. The prevalence of post traumatic stress disorder in survivors of ICU treatment: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(9):1506–1518. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0730-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Battle CE, Davies G, Evans PA. Long term health-related quality of life in survivors of sepsis in South West Wales: an epidemiological study. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e116304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heyland DK, Hopman W, Coo H, Tranmer J, McColl MA. Long-term health-related quality of life in survivors of sepsis. Short Form 36: a valid and reliable measure of health-related quality of life. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(11):3599–3605. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200011000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elliott D, McKinley S, Alison J, et al. Health-related quality of life and physical recovery after a critical illness: a multi-centre randomised controlled trial of a home-based physical rehabilitation program. Crit Care. 2011;15(3):R142. doi: 10.1186/cc10265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cuthbertson BH, Rattray J, Campbell MK, et al. The PRaCTICaL study of nurse led, intensive care follow-up programmes for improving long term outcomes from critical illness: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;339:b3723. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Engel C, Brunkhorst FM, Bone HG, et al. Epidemiology of sepsis in Germany: results from a national prospective multicenter study. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(4):606–618. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0517-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levy MM, Artigas A, Phillips GS, et al. Outcomes of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign in intensive care units in the USA and Europe: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(12):919–924. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Douglas SL, Daly BJ, Kelley CG, O'Toole E, Montenegro H. Chronically critically ill patients: health-related quality of life and resource use after a disease management intervention. Am J Crit Care. 2007;16(5):447–457. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club. 1995;123(3):A12–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jackson JC, Ely EW, Morey MC, et al. Cognitive and physical rehabilitation of intensive care unit survivors: results of the RETURN randomized controlled pilot investigation. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(4):1088–1097. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182373115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jones C, Backman C, Capuzzo M, et al. Intensive care diaries reduce new onset post traumatic stress disorder following critical illness: a randomised, controlled trial. Crit Care. 2010;14(5):R168. doi: 10.1186/cc9260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Czerwonka AI, Herridge MS, Chan L, Chu LM, Matte A, Cameron JI. Changing support needs of survivors of complex critical illness and their family caregivers across the care continuum: a qualitative pilot study of Towards RECOVER. Journal of critical care. 2015;30(2):242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Der Schaaf M, Bakhshi-Raiez F, Van Der Steen M, Dongelmans DA, De Keizer NF. Recommendations for intensive care follow-up clinics; report from a survey and conference of Dutch intensive cares. Minerva Anestesiol. 2015;81(2):135–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Egerod I, Risom SS, Thomsen T, et al. ICU-recovery in Scandinavia: a comparative study of intensive care follow-up in Denmark, Norway and Sweden. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2013;29(2):103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elliott D, Davidson JE, Harvey MA, et al. Exploring the scope of post-intensive care syndrome therapy and care: engagement of non-critical care providers and survivors in a second stakeholders meeting. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(12):2518–2526. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Burns KE, Zubrinich C, Tan W, et al. Research recruitment practices and critically ill patients. A multicenter, cross-sectional study (the Consent Study) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(11):1212–1218. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201208-1537OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1(3):176–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCarney R, Warner J, Iliffe S, van Haselen R, Griffin M, Fisher P. The Hawthorne Effect: a randomised, controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Day SJ, Altman DG. Statistics notes: blinding in clinical trials and other studies. BMJ. 2000;321(7259):504. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7259.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Elia Marinos. The ‘MUST’ report Nutritional screening for adults: a multidisciplinary responsibility Development and use of the ‘Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool’ (MUST) for adults. British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (BAPEN); 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Garrouste-Orgeas Maité, et al. Body mass index. Intensive care medicine 30.3. 2004:437–443. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1: Secondary outcome analysis of overall survival

eFigure 2: Venn diagram on intervention delivery

eFigure 3: Network and functioning of intervention actors

eTable 1: Primary outcome confirmatory test and sensitivity analyses

eTable 2: Secondary outcomes analysis of all SF-36 scales

eTable 3: Secondary outcomes analysis of measures of mental health

eTable 4: Secondary outcomes analysis of functional measures

eTable 5: Secondary outcomes analysis of patient reported process-related measures

eTable 6: Baseline data (at ICU discharge) on secondary outcome measures

eTable 7: Clinical significance on secondary outcome scales

eTable 8: Secondary outcomes analysis of process-related measures derived from PCP

eTable 9: Item analysis of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care questionnaire (PACIC)

eTable 10a: Topics of all Monitoring calls stratified by clinical urgency

eTable 10b: Monitoring stratification on patient level