Abstract

Familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy (FAP) is a systemic amyloidosis mainly caused by amyloidogenic transthyretin (ATTR). This incurable disease causes death ∼10 years after onset. Although it has been widely accepted that conformational change of the monomeric form of transthyretin (TTR) is very important for amyloid formation and deposition in the organs, no effective therapy targeting this step is available. In this study, we generated a mouse monoclonal antibody, T24, that recognized the cryptic epitope of conformationally changed TTR. T24 inhibited TTR accumulation in FAP model rats, which expressed human ATTR V30M in various tissues and exhibited non-fibrillar deposits of ATTR in the gastrointestinal tracts. Additionally, humanized T24 (RT24) inhibited TTR fibrillation and promoted macrophage phagocytosis of aggregated TTR. This antibody did not recognize normal serum TTR functioning properly in the blood. These results demonstrate that RT24 would be an effective novel therapeutic antibody for FAP.

Keywords: amyloid, antibody, antibody engineering, drug design, fibril, FAP, transthyretin

Introduction

Amyloidosis is a group of diseases causing functional disorders because of deposits of fibrillated protein in various tissues and includes Alzheimer's and prion disease (1). Familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy (FAP)4 is an autosomal dominant hereditary amyloidosis that primarily occurs as a result of mutation of the transthyretin (TTR) gene (2). FAP is caused by the accumulation of TTR amyloid around the heart, kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, eyes, and peripheral nerves (2). This disease generally appears during middle age and exhibits dysfunction in the affected areas. FAP causes death ∼10 years after onset (2). Thus far, more than 130 mutations have been reported in the TTR gene (3). Val-30 mutated to Met (V30M) TTR is the most common mutation (4). Patients with amyloidogenic TTR (ATTR) V30M FAP have mainly been reported in Portugal, Sweden, and Japan (4).

Native TTR behaves as a tetramer comprising four identical subunits, each of which contains 127 amino acid residues and has a molecular mass of 14 kDa (5). Each monomer contains eight β-strands, which are formed by antiparallel four-strand β-sheets (5). This protein binds to the retinol-binding protein and thyroxine in the blood (5). TTR is primarily produced in the liver and choroid plexus. Although blood levels can be as high as 0.25 g/liter, its half-life is only 2 days (2, 4, 5). Dissociation of the tetramer into monomers and conformational change of the monomers are very important steps for TTR fibrillization (Fig. 1) (6, 7). It is suggested that the rate-limiting step may account for dissociation into monomers (8). However, all toxic species of TTR have not been identified, and therapeutic approaches for FAP targeting various species of TTR have yet to be established (3).

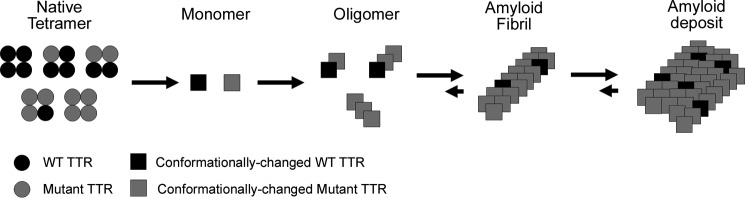

FIGURE 1.

Pathway of TTR fibrillization. Native TTR behaves as a tetramer in the blood. The blood of heterologous patients with both WT TTR and TTR mutant proteins contains five tetramer patterns. If the TTR mutants are included in a tetramer, the tetramer easily dissociates into monomers compared with the WT TTR tetramer. It is considered that TTR monomers cause conformational change, the fibrillization step gradually progresses via oligomer state, and then TTR amyloids deposit in the various organs such as peripheral nerves. Dissociation into monomers and conformational change of the monomers are very crucial steps for TTR fibrillization.

Liver transplantation (LT) is the most common treatment for FAP. By disconnecting the supply of mutant TTR from the liver, LT suppresses the progression of symptoms (2). Although pathology progression delay is observed after LT, deposits of TTR to organs, including the eyes and heart, may still progress; there have been many reports of progression of symptoms to these organs (9, 10). Recently, “TTR stabilizers” have been approved as therapeutic drugs (3). These drugs kinetically stabilize TTR and are expected to inhibit the dissociation of tetramers into monomers of TTR. Tafamidis was approved in the European Union and Japan (11), and clinical trials of diflunisal have been conducted worldwide (3). These TTR stabilizers delay peripheral neuropathy but cannot completely suppress pathology progression. To completely suppress pathology progression, it is necessary to suppress TTR fibrillization and also to remove the amyloid deposits. Several therapeutic drugs, such as siRNA, which target the wild type (WT) TTR RNA (12), are currently undergoing clinical development, but their effect on TTR deposits in organs is unclear.

It is known that during TTR fibrillization, new epitopes (cryptic epitopes) are exposed on the molecular surface with a conformational change of TTR (13). It has been reported that by immunizing FAP model mice with a mutant TTR that has exposed cryptic epitopes, antibodies that recognize the cryptic epitopes of TTR are generated, and these antibodies can reduce the deposition of TTR amyloids (14, 15). Likewise, Gustavsson et al. (16) reported that when they prepared 10 anti-peptide sera (antisera) of TTR, only antisera against the TTR(115–124) region strongly reacted with the amyloids in FAP patients and did not react to serum TTR or normal (non-FAP) pancreas. Furthermore, analysis of the steric structures surrounding TTR114 has been reported to show that they are located in the intermolecular interaction interface when in the tetramer state (17). From these reports, we consider the TTR(115–124) region to be a “cryptic epitope” that is hidden from the protein surface when in the tetramer form and is exposed on the surface when it changes into the monomer form. Bergström et al. (18) generated rabbit polyclonal antibodies against residues 115–124 of the human TTR, a cryptic epitope. When these antibodies were administered to FAP model rats (19), TTR deposits in the intestinal tract were significantly reduced (20). The above suggests that the antibody recognizes the cryptic epitope of TTR, interacts with conformationally changed TTR and TTR amyloid, may inhibit fibrillization, and remove the TTR amyloids. Therefore, the antibody that recognizes the cryptic epitope of TTR may have the potential to become a novel therapeutic drug for FAP.

In this study, with the aim of developing a new therapeutic drug for FAP, we report on the novel monoclonal antibody T24, which recognizes the residues 115–124 (cryptic epitope) of TTR, and we introduce the biological activities and efficacies of T24 and humanized T24 (RT24) antibodies.

Results

T24 Recognized 118-122 Region of Human TTR

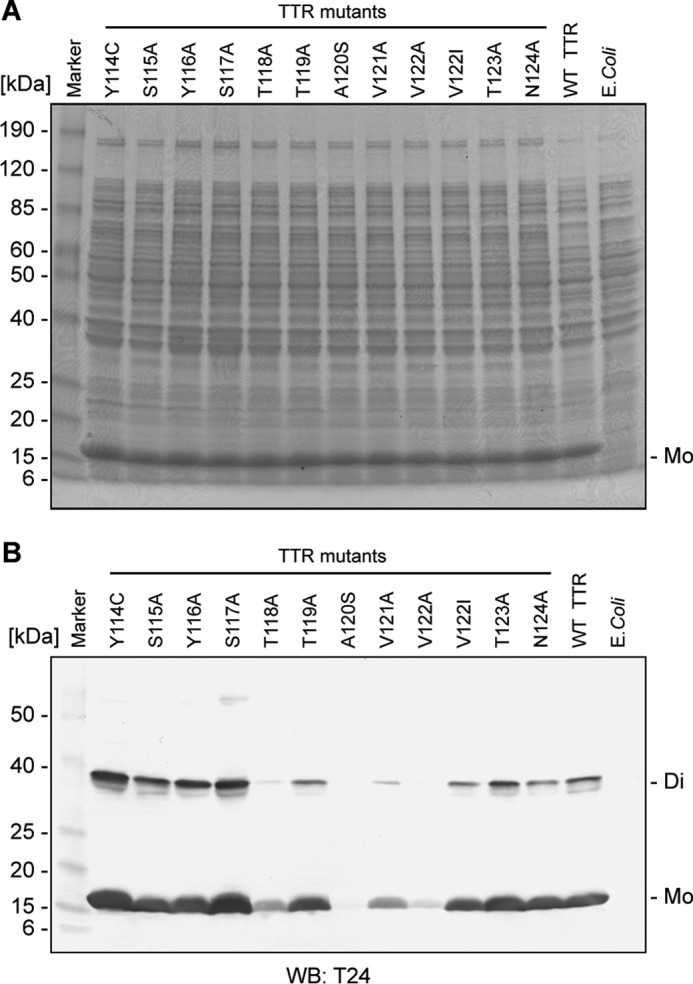

The antigen binding activity of the antibodies of the obtained hybridomas was evaluated by ELISA, and an excellent binding activity to the TTR(115–124) peptides was found in hybridoma clone T24. To completely analyze the epitope of the T24 antibody, the reactivity analysis of T24 was performed using the alanine substitution variant of the TTR(115–124) region. Coomassie Brilliant Blue stain analysis and Western blotting analysis, using T24 antibody, alanine substitution mutants from residues 114 to 124 (except for Y114C, A120S, and V122I, which were mutations reported in patients) of the human TTR expressed in Escherichia coli and the supernatants from disrupted cell pellets when applied to SDS-PAGE are shown in Fig. 2, A and B (Western blotting analysis), respectively. Reactivity of T24 antibody was reduced or eliminated in the TTR mutant from residues 118 to 122; therefore, the epitope of T24 was thought to be TTR(118–122).

FIGURE 2.

T24 recognized the TTR residue in the 118–122 region. A, SDS-PAGE analysis of recombinant TTR mutants. E. coli strain M15 was transfected with the recombinant TTR mutant from residue 114 to 124 expression vectors and cultured. After IPTG induction of recombinant TTR expression, the cell fraction was electrophoresed under reducing conditions on 8–16% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and the gel was stained by Coomassie Brilliant Blue. B, reactivity of T24 against recombinant TTR mutants. The solubilized cell suspension was subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting (WB) analysis using T24 antibody. E. coli, M15 without TTR expression vector, Di, TTR dimer; Mo, TTR monomer.

T24 Specifically Recognized TTR Amyloid in FAP Patients

To clarify the binding specificity of T24, we analyzed binding reactivity to human blood and amyloids in FAP patients using ELISA, Western blotting, and immunohistological staining.

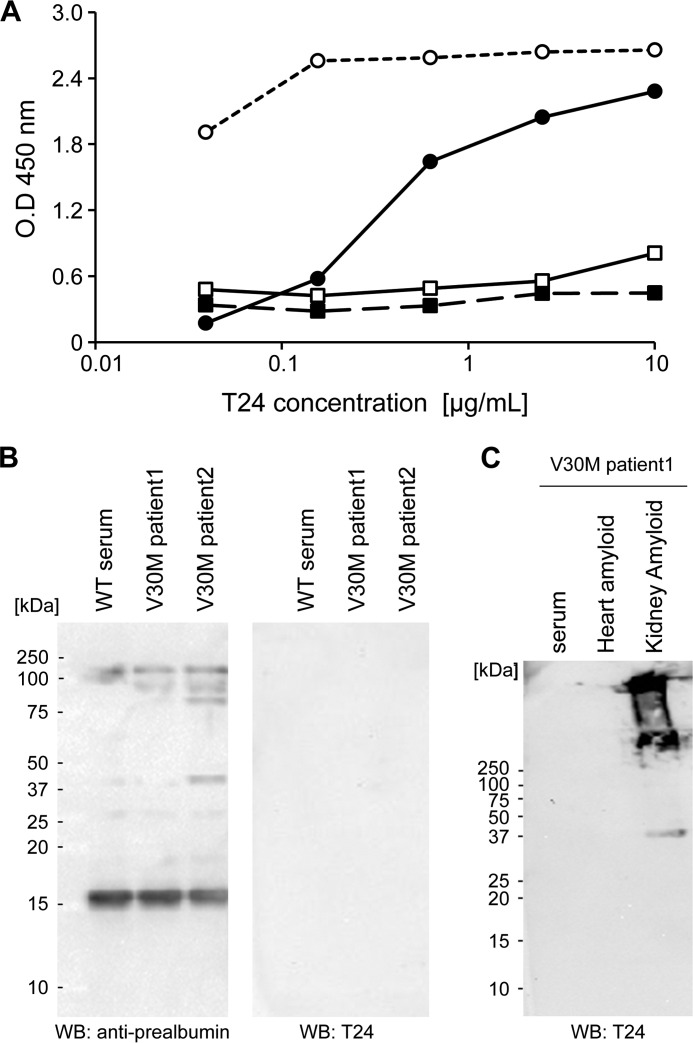

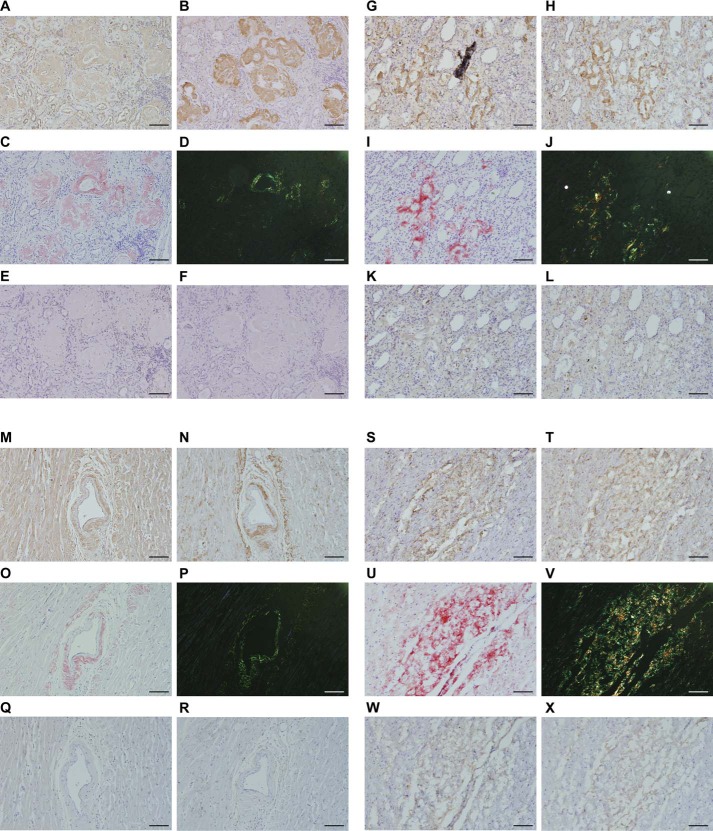

In ELISA, T24 specifically reacted with the TTR(115–124) peptide and acid-treated WT TTR fibrils from the human serum (Fig. 3A). Conversely, this antibody did not react with the human serum from healthy volunteers or V30M TTR FAP patients. In Western blotting, the anti-prealbumin antibody reacted with the TTR monomer and some of the proteins in the human serum, but T24 did not react with the human serum from healthy volunteers or V30M TTR FAP patients (Fig. 3B). Additionally, we performed Western blotting to reveal the T24 specificity against TTR amyloids extracted from the kidney and heart of FAP patients. T24 specifically recognized TTR amyloids from the kidney (Fig. 3C). In immunohistochemical staining using paraffin and frozen sections, T24 specifically reacted with amyloids in the heart (Fig. 4, A and G) and amyloids in the kidney (Fig. 4, M and S) from FAP V30M TTR patients. These areas showed high consistency with positive areas of anti-prealbumin antibody (Fig. 4, B, H, N, and T), Congo red stain (Fig. 4, C, I, O, and U), and Congo red polarized light (Fig. 4, D, J, P, and V). There were no specific immunoreactivities using the isotype control (Fig. 4, E, K, Q, and W) and secondary antibody alone (Fig. 4, F, L, R, and X).

FIGURE 3.

T24 antibody specifically reacted with TTR amyloid, but not serum TTR, from FAP patients. A, T24 reactivity was assessed by ELISA. Human serum-derived WT-TTR fibril by acidic treatment (black circle), BSA-conjugated TTR peptide (white circle), serum from a healthy volunteer (black square), and serum from a V30M FAP patient (white square) were immobilized on an immunoplate, and the reactivity of T24 against each antigen was analyzed by ELISA. B and C, reactivity of T24 was assessed by Western blotting (WB). B, serum from a healthy volunteer or V30M FAP patient was applied to SDS-PAGE under non-reducing conditions and then analyzed by Western blotting with polyclonal anti-prealbumin or T24 antibody. C, serum or extracted amyloids from the heart and kidney from a V30M FAP patient were applied to SDS-PAGE, and then analyzed by Western blotting with T24 antibody.

FIGURE 4.

T24 antibody recognized TTR amyloids in the kidney and heart from FAP patients. T24 reactivity was evaluated by immunohistochemical analysis. Paraffin sections (A–F and M–R) or frozen sections (G–L and S–X) of the kidney glomerulus tissue (A–L) or the heart tissue (M–X) from a V30M FAP patient (67-year-old man) were prepared. After Congo red and hematoxylin staining (C, I, O, and U), the presence of apple-green birefringence under polarized light confirmed the presence of amyloid deposits (D, J, P, and V). For immunohistochemical staining, paraffin-embedded and frozen slides were treated with periodic acid, followed by immunostaining using T24 antibody (A, G, M, and S), anti-prealbumin antibody (B, H, N, and T), isotype control (E, K, Q, and W), or no primary antibody (secondary antibody only) (F, L, R, and X). Areas that are stained brown are deposits of TTR amyloids. Bars, 200 μm.

RT24 Antibody Showed Reactivity Similar to T24

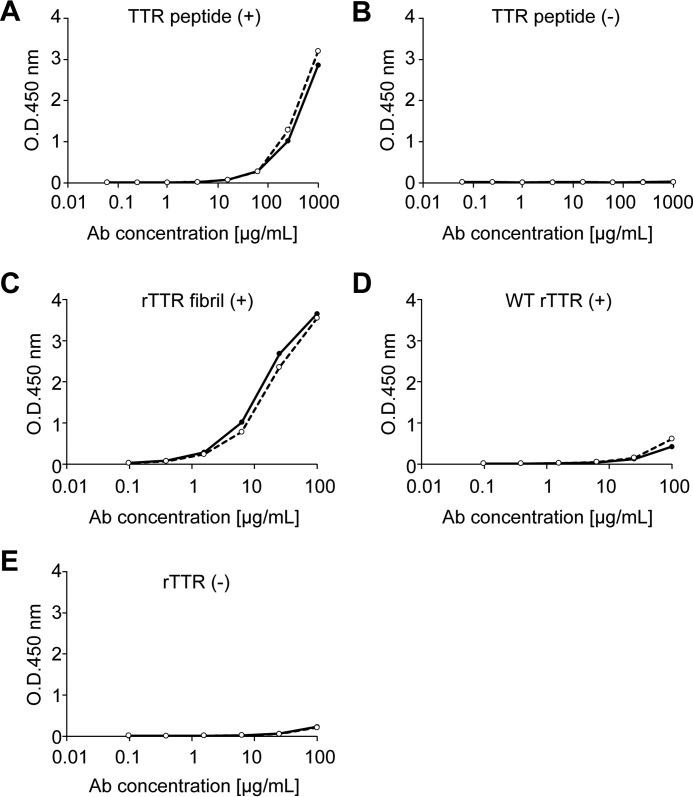

Next, we performed the humanization of T24 murine antibody. The V region gene of T24 was isolated by T24-producing hybridoma, and T24 was humanized by CDR grafting as described under “Experimental Procedures.” To clarify the binding specificity of RT24, we analyzed binding reactivity using ELISA. According to ELISA, RT24 specifically recognized the immunized antigen (TTR(115–124) peptide) (Fig. 5A) and the TTR fibril formed by acidic treatment (Fig. 5C), similar to that with chimera T24 antibody (CT24). A very weak reaction against WT TTR (Fig. 5D) and no response in the absence of the peptide or recombinant TTR (Fig. 5, B and E) were observed. It was found that RT24 and T24 have the same binding activity.

FIGURE 5.

RT24 antibody showed reactivity similar to T24. Reactivity of RT24 was assessed by ELISA. A and B, biotin-conjugated TTR(115–124) peptide (A) or no peptide (B) immobilized to the streptavidin-coated plate. C–E, V30M TTR fibril formed by acidic treatment (C), purified recombinant WT TTR (D), and no TTR (E) immobilized to the nickel-chelate plate. The reactivity of CT24 (solid line) or RT24 (broken line) against each antigen was analyzed by ELISA.

RT24 Specifically Interacted with Recombinant TTR-derived Fibrils but Not WT TTR Tetramer

We analyzed whether RT24 recognizes various TTR fibrils, which has been reported in patients, using recombinant TTR-derived fibrils. Consequently, it was found that RT24 recognized various TTR fibrils, which were reported in patients but not purified native (non-aggregated) WT TTR (Fig. 6B).

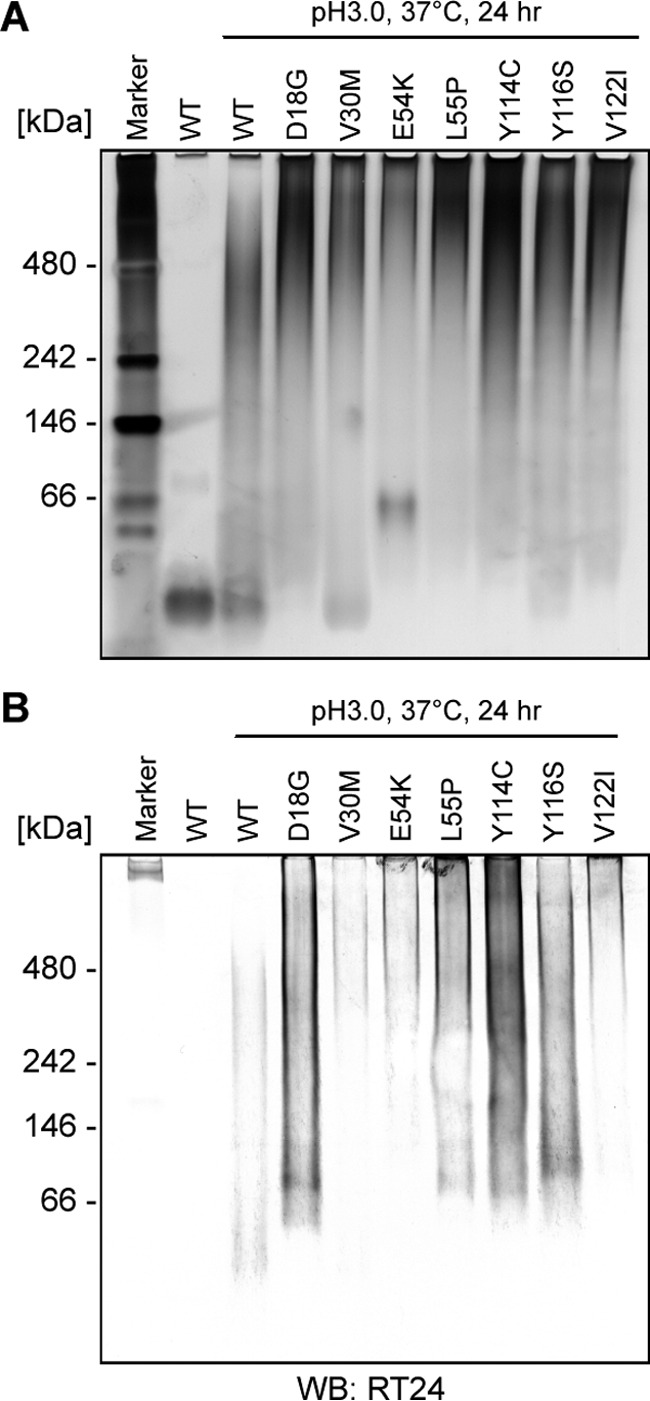

FIGURE 6.

RT24 specifically interacted with the TTR fibrils that have been reported in patients. Native-PAGE analysis using TTR fibrils that have been reported in patients. Purified recombinant WT TTR or purified recombinant WT/mutant TTR fibrils treated at pH 3.0 were applied onto 4% native-polyacrylamide gel, and the gel was stained by silver staining (A), followed by Western blotting (WB) using RT24 antibody (B).

RT24 Specifically Interacted with Conformationally Changed TTR but Not with the TTR Tetramer in Liquid Phase

To clarify the binding specificity of liquid-phase system, we analyzed binding activity using the SPR method. RT24 specifically interacted with the WT TTR fibril and V30M TTR fibril formed by acidic treatment, and no interactions were observed with recombinant WT TTR and V30M TTR (Fig. 7). Isotype controls had no interaction. It was found that RT24 specifically recognized conformationally changed TTR in the liquid phase.

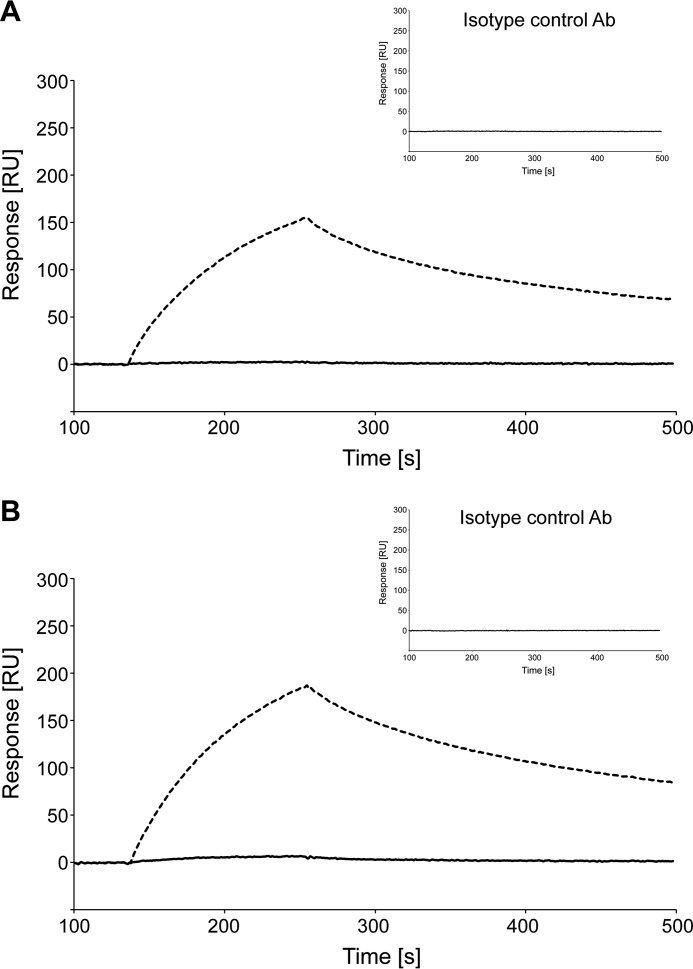

FIGURE 7.

RT24 recognizes the TTR fibril but not the TTR tetramer in a liquid-phase system. RT24 specificity in a liquid-phase system was analyzed by SPR analysis. A, purified recombinant WT TTR (solid line) and WT TTR fibril treated at pH 3.0 (broken line) were immobilized on a sensor chip. RT24 and isotype control (inset) were injected during the association phase for 2 min. The dissociation phase was performed over a period of 60 min. B, purified recombinant V30M TTR (solid line) and V30M TTR fibril treated at pH 3.0 (broken line) were immobilized on a sensor chip. Subsequent operations were performed in the same manner as A. Ab, antibody.

RT24 Inhibited V30M TTR Fibrillization

A fibrillization inhibition assay was performed to evaluate whether RT24 inhibits V30M TTR fibrillization. We found that RT24 significantly inhibited V30M TTR fibrillization in an antibody concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 8) and that IC50 of RT24 is ∼150 nm. However, SPR analysis shows that the dissociation constant (KD) of RT24 is 300–420 nm (data not shown), so this result for the evaluation of RT24's activity is reasonable.

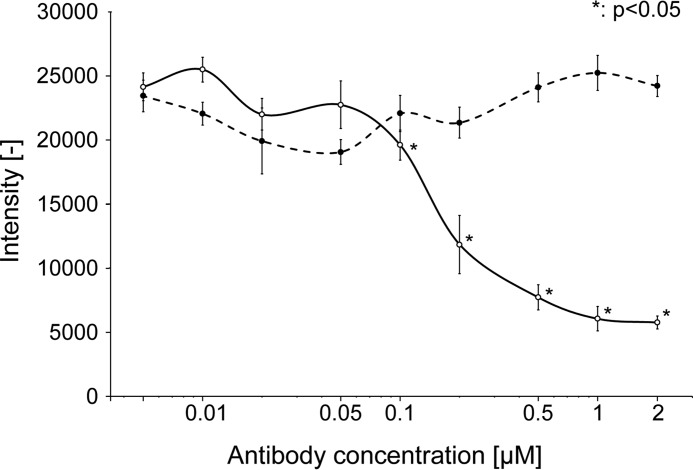

FIGURE 8.

RT24 inhibits V30M TTR fibrillization. Fibrillization inhibition assay was performed. RT24 (solid line) or isotype control antibody (broken line) were mixed with recombinant purified V30M TTR protein in PBS containing 0.1% sodium deoxycholate and incubated at 37 °C for 3 days (n = 3). The fibrillization level was measured by thioflavinT assay. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. Student's t test was used for evaluation. A p value less than 0.05 (*) was considered statistically significant.

RT24 Promoted Macrophage Phagocytosis of the TTR Fibril

The macrophage phagocytic ability test was performed to investigate whether RT24 antibody promotes the ability of macrophage to phagocytose the TTR fibril. This test mimics the process wherein macrophages remove TTRs deposited in the tissues of TTR patients. RT24 specifically promoted phagocytosis of the TTR fibril (Fig. 9A). No phagocytic activity changes were observed against native (non-aggregated) TTR (Fig. 9B). Thus, RT24 promotes the phagocytic activity of macrophages toward the TTR fibril.

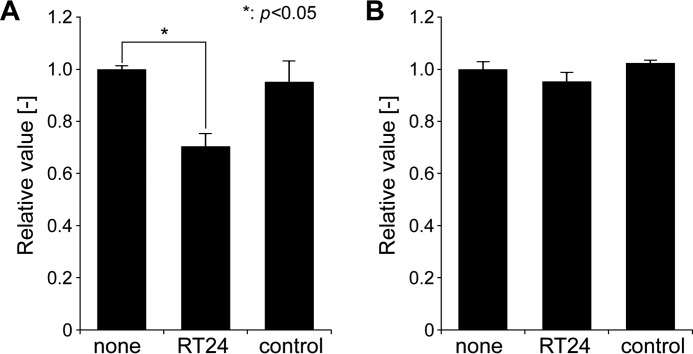

FIGURE 9.

RT24 promotes macrophage phagocytosis against aggregated TTR. A macrophage phagocytic ability test was performed to investigate the clearance via antibodies against misfolded TTR. Aggregated TTR were generated from native V30M TTR by incubating for 24 h at 37 °C under acidic conditions (pH 4.0). Aggregated TTR (A) or native TTR (B) or were co-cultured with iPS-MLs in medium containing antibodies (RT24, isotype control, or none, n = 3). After incubation for 2 days, reduction of TTR in the medium was evaluated by ELISA using anti-prealbumin antibody. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. Student's t test was used for evaluation. A p value less than 0.05 (*) was considered statistically significant.

T24 Inhibited TTR Deposits in FAP Model Rats

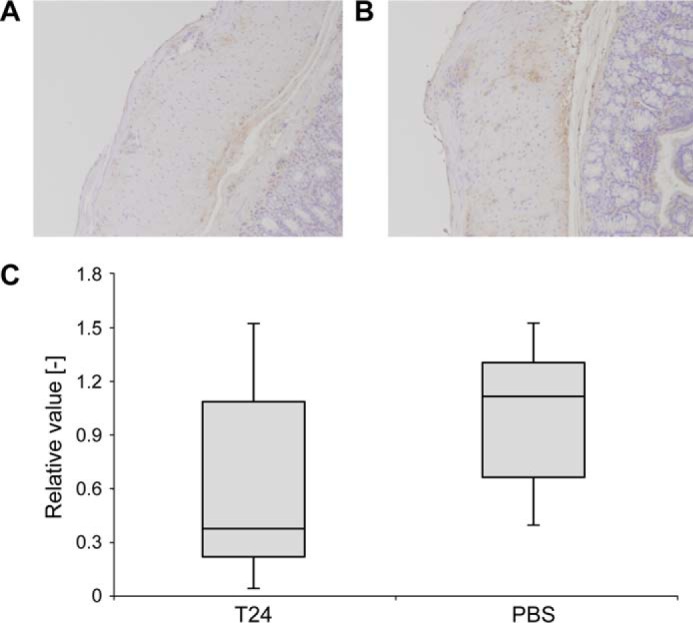

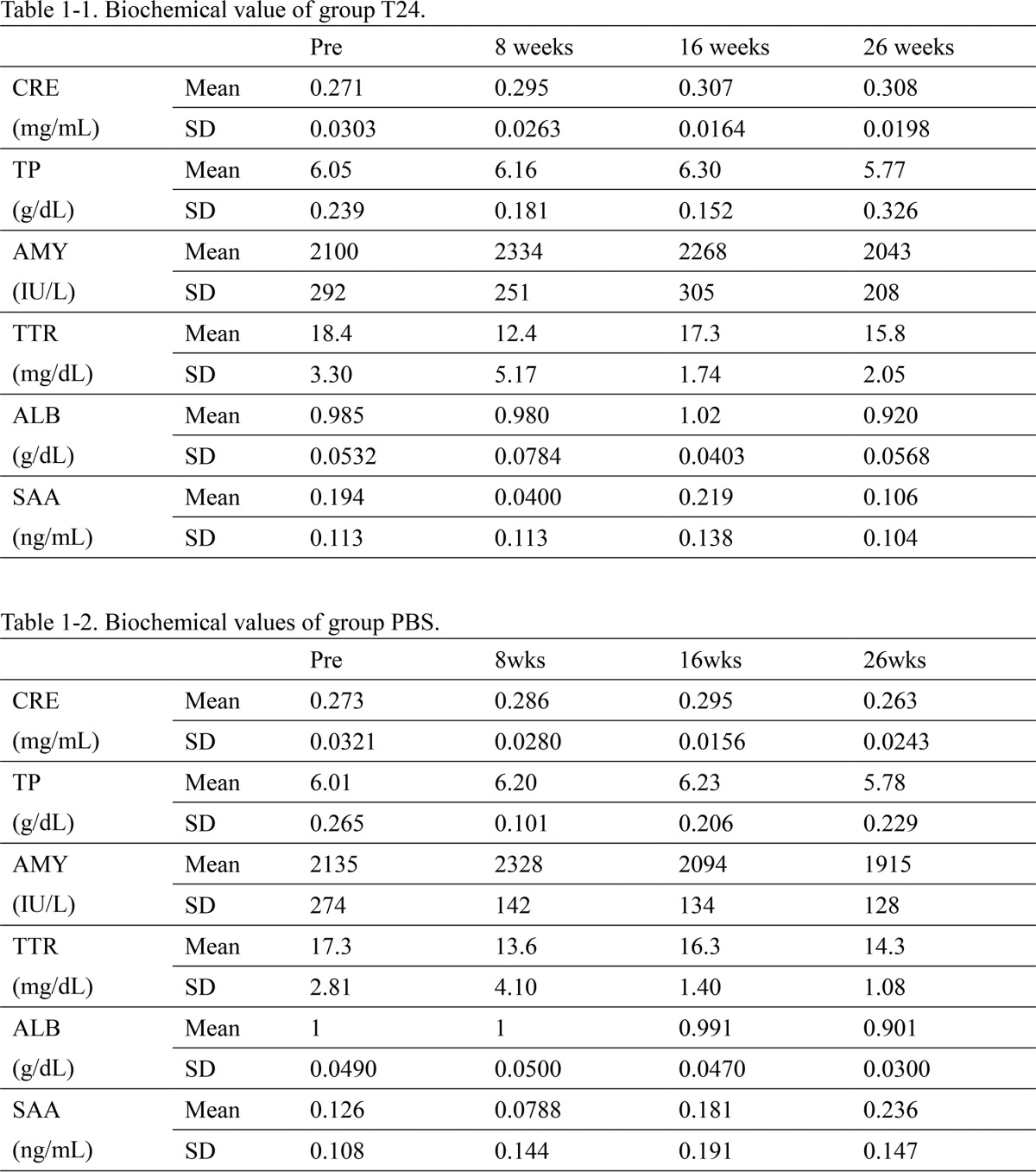

Using FAP model rats, we performed an efficacy evaluation test to test whether T24 suppresses the deposition of TTR amyloid. Comparing the stained images after administration of T24 or PBS, the group administered with T24 (T24 group, Fig. 10A) showed greater reduction of TTR-positive areas than that administered PBS (PBS group, Fig. 10B). Semi-quantitatively, the T24 group tended to have a greater reduction in the amount of TTR deposits than in the PBS group (Fig. 10C). Sera were collected once a week, and analysis of blood biochemistry was performed. No abnormal values were observed. Long-term administration of T24 did not affect renal, liver, or pancreatic function (Table 1).

FIGURE 10.

T24 inhibits TTR deposition in FAP model rats. Using FAP model rats, we performed efficacy evaluation to test whether T24 suppresses the deposition of TTR amyloid. TTR Tg rats received intravenous administration of T24 or PBS once a week for 26 weeks. Paraffin sections of rat colons were stained using anti-prealbumin antibody; the amount of TTR deposits in the muscle layer of the large intestine was detected and compared between the groups (group T24, n = 8, and group PBS, n = 7). A and B, representative images of paraffin sections of group T24 (A) or PBS (B). Stained areas in brown indicate deposits of TTR fibril in the muscle layer. C, stained areas were quantitated as the amount of TTR accumulation for each individual. The average value of the group PBS was regarded as “1,” and the distribution of the relative value was displayed by a boxplot.

TABLE 1.

Biochemical value of groups T24 and PBS

During the efficacy study, blood was collected once a week; blood levels of creatinine (CRE indicates kidney function), total protein (TP indicates liver function), amylase (AMY indicates pancreatic function), TTR, albumin and serum amyloid A were analyzed. The data showed average value between individuals. SAA is serum amyloid A and ALB is albumin.

Discussion

On the basis of the concept that an antibody that specifically recognizes the cryptic epitope of TTR could be a novel therapeutic drug of FAP, we generated monoclonal antibody T24, which recognized residues 118–122 of the human TTR. This antibody recognizes various TTR species from conformationally changed monomers to fibrils. Humanized antibody, RT24, also has the same specificity with T24.

These antibodies have the following characteristics. First, RT24 inhibited V30M TTR fibrillization in an antibody concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 8). This activity is very important for preventing TTR from being deposited in the tissue. Second, RT24's activity promotes the phagocytic capacity against the TTR fibril (Fig. 9). This activity is thought to be effective in removing TTR amyloids deposited in various tissues. Third, T24 specifically recognized TTR amyloids extracted from patients and did not react with the serum from FAP patients (Fig. 3). This specificity is expected to be effective in the serum and cause few side effects. Finally, T24 tended to reduce TTR deposits in FAP model rats (Fig. 10). For the efficacy study, we performed long-term administration (6 months) of the T24 antibody, which is assumed to have less immunogenicity, instead of RT24. During the administration period, the increase in anti-T24 antibodies and abnormal biochemical values were not observed (Table 1 and data not shown). Therefore, the long-term administration of T24 is assumed to be safe. In this study, a difference in TTR deposits in the muscle layer of the large intestine was observed between the groups that were administered T24 and PBS; however, it was not statistically significant (Fig. 10C). This result may be due to individual differences in the amount of TTR deposits in FAP model rats. Although TTR deposits increase until 3–9 months, there are large differences between individuals (data not shown). The effects of T24 may be masked by these individual differences.

TTR antibodies generated using the same concept have been reported by Goldsteins et al. (13) and Phay et al. (21). Goldsteins et al. (13) generated mAb39-44 and mAb56-61 antibodies that reacted with TTR, which caused conformational changes, and these antibodies also recognized the V30M TTR amyloid. However, these antibodies did not inhibit TTR fibrillization, and Goldsteins et al. (13) only mentioned the possibility of utilizing these antibodies for diagnosis. Phay et al. (21) generated mouse monoclonal antibody 2T5C9, which specifically recognized TTR amyloids from FAP patients by ELISA and immunohistochemical analysis. However, the biological activities of this antibody were not reported, and Phay et al. (21) only mentioned the possibility of utilizing this antibody for diagnosis. Therefore, no antibody has been reported that specifically recognizes conformationally changed TTR but does not recognize normal serum TTR functioning properly in the blood, that shows biological activities in vitro and in vivo, and that is suitable for administration to humans.

Antibodies against amyloidosis have been actively developed. In particular, knowledge regarding the treatment of Alzheimer's disease is beginning to expand (22). In Alzheimer's disease, it has been reported that removing the amyloid β (Aβ) fibrils deposited in the brain does not lead to an improvement in the clinical condition. Therefore, it has been suggested that Aβ oligomers and not Aβ fibrils are the pathogenic molecules (23). For treatment, we need to target all Aβ intermediates from the conformationally changed monomer to the Aβ fibril (22). In TTR amyloidosis, although the expression of ATTR was inhibited by LT, TTR deposition progressed, and there were many cases of the disease being exacerbated (9, 10). Even if both diseases are recognized as amyloidosis, the effects of Alzheimer's disease and TTR amyloidosis on the organs may be different. For the treatment of FAP, we may need to both inhibit TTR fibrillation and remove amyloid deposits. Thus, RT24, which targets conformationally changed TTR via fibrils and TTR amyloids, is expected to not only inhibit deposition of mutated TTR but also remove amyloid deposits (Fig. 10); therefore, this antibody has the potential to be a novel therapeutic drug for FAP.

RT24 recognized various recombinant TTR (D18G, E54K, L55P, Y114C, Y116S, and V122I) amyloids that have been reported in patients (Fig. 6). This result suggests that RT24 may work effectively against patients with mutations other than V30M ATTR. Because this antibody reacted with conformationally changed WT TTR (Fig. 6B), administration of RT24 may be effective for senile systemic amyloidosis, which is caused by the deposition of WT TTR amyloids and associated with aging (10). With regard to the TTR depositions in the heart, T24 did not detect TTR amyloids extracted from hearts obtained from FAP patients (Fig. 3C); however, specific T24 immunoreactivities were observed in the heart amyloids from a FAP V30M TTR patient using immunohistochemical staining of heart sections (Fig. 4, M and S). For this reason, it is assumed that T24 may also recognize TTR deposits in heart tissue. Therefore, it is expected that RT24 works effectively against patients with various TTR mutations, and this new approach has the potential to be adapted for treatment of senile systemic amyloidosis.

Another interesting finding in this study was that we established fibrillization inhibition assay under neutral conditions. Until now, fibrillization inhibition assays have generally been performed in the screening stage of antibody drugs for the treatment of amyloidosis. With respect to the V30M TTR fibrillization assay, there are some examples that have been applied to small molecules (24), but no examples have been applied to antibodies. This is probably because acidic conditions are required to fibrillize V30M TTR in a short time, and this process denatures antibodies. We treated V30M TTR by adding sodium deoxycholate to PBS and observed V30M TTR fibrillization in a short time under neutral conditions, without denaturation of antibodies. We previously confirmed that V30M TTR fibril formation kinetically continues in the presence of PBS containing sodium deoxycholate (data not shown). Therefore, using the V30M TTR fibrillization assay, the activity of antibodies could be evaluated (Fig. 8). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to perform fibrillization inhibition assay under neutral conditions.

Various approaches have been taken in the research and development of treatments for FAP, and several therapeutic drugs are expected to be approved in the near future. Among them, antibody therapy has a unique mechanism and high specificity and could meet the medical needs as a novel therapeutic treatment with excellent safety and efficacy. We hope that RT24 may be used as an antibody therapy for FAP in the future.

Experimental Procedures

Human Samples, Animals, Peptide, Plasmids, and Antibody

All studies with human samples were conducted in accordance with the current version of the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethical committee of Kumamoto University approved this study. Animals were maintained in a specific pathogen-free environment at the Center for Animal Resources and Development, Kumamoto University. Animals were handled according to Kumamoto University's animal care policy. Peptides in which cysteine was added at the amino-terminal region of the human TTR(115–124) peptide were prepared by chemical synthesis (Sigma). KLH or BSA was conjugated with cysteine residue using an Immuject® Immunogen EDC kit with mcKLH and BSA (Thermo). WT TTR DNA was cloned by PCR using human liver Marathon-Ready cDNA (Clontech) as a template. The cloned TTR DNA fragment was introduced into pQE-30 (Qiagen) to construct a WT human TTR expression vector. The human TTR mutant (D18G, V30M, E54K, L55P, Y114C, S115A, Y116A, Y116S, S117A, Y118A, T119A, A120S, V121A, V122A, V122I, T123A, and N124A) expression vectors were prepared by site-directed mutagenesis using the above-mentioned WT human TTR expression vector as a template. Anti-hepatitis B surface antigen monoclonal antibody was used as an isotype control (negative control).

Preparation of Recombinant Mutant TTRs

WT TTR and TTR mutant proteins were expressed by E. coli and purified using a previously described method (25). E. coli strain M15 was transfected with each expression vector of WT TTR or variant TTRs, such as D18G, V30M, E54K, L55P, Y114C, Y116S, or V122I. Subsequently, each E. coli clone was cultured with 20 ml of Luria-Bertani medium/ampicillin (50 μg/ml)/kanamycin (25 μg/ml) at 37 °C. When A600 was 0.5, IPTG was added at a final concentration of 10 mm, and the culture was incubated overnight. The cells were collected from the culture by centrifugation and resuspended in Buffer A (50 mm phosphate buffer (PB) + 0.3 m NaCl + 10 mm imidazole + 20 mm 2-mercaptoethanol). The suspension was sonicated for 15 min and then centrifuged to collect supernatant. The supernatant was subjected to His tag purification with nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen) and the eluent fraction containing the recombinant TTRs was dialyzed against 20 mm NaHCO3. The recombinant TTRs after dialysis were purified by gel filtration with Superdex 75 (GE Healthcare) using 10 mm PB (pH 7.5), and a fraction of tetrameric TTR was used as purified recombinant TTRs.

Generation of Monoclonal Antibodies

TTR knock-out mice (26) were immunized with a 1:1 emulsification of KLH-conjugated TTR peptide and Freund's complete adjuvant (Difco). Over 2 weeks after the first immunization, these mice were immunized with a 1:1 emulsification of KLH-conjugated TTR peptide and Freund's incomplete adjuvant (Difco). Antibody titer was confirmed by ELISA. After a sufficient increase in antibody titer was confirmed, the spleen cells were collected from the mouse and fused with mouse myeloma cells P3U1 using the PEG method (27). At days 7–11 after the inoculation in HAT medium, the binding activity to TTR(115–124) peptide was screened via ELISA using the hybridoma supernatants.

Epitope Analysis

E. coli strain M15 was transfected with each recombinant TTR mutant (Y114C, S115A, Y116A, S117A, Y118A, T119A, A120S, V121A, V122A, V122I, T123A, or N124A) expression vector individually and cultured in 20 ml of Luria-Bertani medium/ampicillin (50 μg/ml)/kanamycin (25 μg/ml) at 37 °C. When A600 was 0.5, IPTG was added at a final concentration of 10 mm, and the culture was incubated overnight. The cultured cell suspension was centrifuged, and the precipitate fraction was resolubilized with Bugbuster (Merck). The resolubilized cell fraction was electrophoresed under reducing conditions on 8–16% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore). The membrane was soaked in 2% skimmed milk/PBST (PBST, PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20) and shaken at room temperature for 1 h to block the membrane. T24 antibody was diluted with 2% skimmed milk/PBST at a concentration of 1 μg/ml, and the membrane was soaked in 10 ml of this antibody solution and shaken at room temperature for 1 h. The membrane was washed with PBST and soaked in HRP-labeled anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (American Qualex International) solution, which was previously diluted 5000-fold with 2% skimmed milk/PBST and shaken at room temperature for 1 h. After washing with PBST, color development was conducted with Ez West Blue (ATTO).

Antibody Reactivity against Patient's Serum and Extracted TTR Amyloid

BSA-conjugated TTR peptides (2 μg/ml), the sera obtained from either a healthy volunteer or a V30M FAP patient or 4 μg/ml human serum-derived WT-TTR fibril treated at pH 3.0 were immoblized on a Maxisorp plate (Nunc) at room temperature. Plates were blocked with PBS containing 1% BSA (1% BSA/PBS). After the plates were coated, they were incubated with T24 antibodies in 1% BSA/PBS at 37 °C for 1 h. The plates were washed in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST). Bound T24 was detected with anti-mouse IgG (H+L)/HRP (Zymed Laboratories Inc.) using the standard method. In addition, analysis of the reactivity of T24 and polyclonal rabbit anti-human prealbumin (TTR) (Dako) was performed by Western blotting against the healthy patient's serum and extracted TTR amyloid from the FAP patient's kidney and heart.

Congo Red and Immunohistochemical Staining

Paraffin-embedded 4-μm-thick sections and frozen 10-μm-thick sections of the kidney and heart from the FAP patient were subjected to Congo red and immunohistochemical staining. After Congo red and hematoxylin staining, the presence of apple-green birefringence under polarized light confirmed the presence of amyloid deposits. For immunohistochemical staining, paraffin-embedded sections were prepared and deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in graded alcohols. Both paraffin-embedded and frozen slides were treated with periodic acid for 10 min at room temperature, after which they were incubated in 5% normal serum for 1 h at room temperature in a moist chamber. Ten micrograms/ml T24 or isotype control was used as the primary antibody and incubated with sections at 4 °C overnight. The secondary antibody was an HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibody (Dako) diluted 1:100 in buffer. The dilution buffer used was 0.5% BSA/PBS. Reactivity was visualized via the DAB Liquid System (Dako), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Humanization of the T24 Antibody

cDNA encoding the murine IgVH and VL were isolated by real time PCR from T24-producing hybridoma. First, to produce CT24, the VH region of T24 was joined with the human IgG heavy-chain constant region gene and ligated to the SalI site of the pCAGGS/mdhfr plasmid (28), and the VL region of T24 was joined with the human IgG light-chain constant region gene and ligated to the SalI site of the pCAGGS plasmid (28). The humanization of T24 was performed using the CDR-grafting method, adding the knowledge from our previous antibody humanization studies and those of other authors (29, 30). To produce RT24, the designed VH and VL regions for RT24 were joined with the human immunoglobulin constant region gene, as described above. Freestyle 293-F cells (Invitrogen) were transfected with RT24 and CT24 expression plasmids using Neofection (ASTEC Co., Ltd.), and the culture was shaken at 125 rpm at 37 °C under environmental conditions of 8% CO2 to express these antibodies. Five days later, transiently expressed culture supernatants were harvested, and then antibodies were purified from the supernatants using protein A chromatography and dialyzed against PBS.

Specificity of the RT24 Antibody

Specificity of the RT24 antibody was assessed by ELISA and SPR using a BIAcore 2000 instrument (GE Healthcare). To prepare the WT and V30M TTR fibril form, purified recombinant WT and V30M TTR protein was adjusted to 3 mg/ml with sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), mixed with an equal volume of fibrillization buffer (0.2 m acetate buffer containing 0.1 m NaCl (pH 3.0)), and incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. After the reaction, fibrillization was confirmed by thioflavinT assay (31). ThioflavinT assay was performed by diluting TTR with 50 mm glycine/NaOH buffer (pH 9.5) so that the final concentrations of thioflavinT and TTR were 20 μm and 15 μg/ml, respectively, and by measuring the fluorescence intensity with spectrofluorometer FP-6500 (Jasco) (excitation wavelength, 450/442 nm; emission wavelength, 482/489 nm). For ELISA, biotin-conjugated TTR(115–124) peptide was diluted to 50 nm with PBS and immobilized to a Nunc Immobilizer Streptavidin Plate (Nunc). Purified recombinant WT (2 μg/ml), V30M TTR fibril, and no proteins were immobilized to the Nunc Immobilizer Nickel-Chelate Plate (Nunc). Plates were blocked with 1% BSA/PBS. After coating, the plates were incubated with RT24 or CT24 antibodies in 1% BSA/PBS at 37 °C for 1 h. The plates were washed five times with PBST. Bound antibodies were detected with anti-human Fc/HRP (Rockland) according to standard procedures. For SPR analysis, WT TTR, V30M TTR, WT TTR fibril, or V30M TTR fibril were immobilized in 10 mm sodium acetate (pH 6.0), at 1000 response units on a CM5 sensor chip (GE Healthcare) using an amine coupling kit (GE Healthcare). RT24 (10 μg/ml) or isotype control was injected during the association phase for 2 min (20 μl/min), with HBS-EP as the running buffer. The dissociation phase, initiated by the passage of HBS-EP alone, was performed over a period of 60 min. Sensor chip surfaces were regenerated by a 30-s injection of 10 mm glycine/NaOH (pH 9.0).

RT24 Reactivity against Recombinant TTR-derived Fibrils

Purified recombinant TTRs (WT, D18G, V30M, E54K, L55P, Y114C, Y116S, and V122I) proteins were incubated for 16 h at 37 °C and pH 3.0. These samples were defined as TTR fibrils. Native-PAGE was performed for 1.5 μg of each TTR fibril, followed by silver staining. Next, the TTR fibrils were analyzed by Western blotting with the RT24 antibody.

Inhibition Assay of V30M TTR Fibrillization

RT24 antibody or isotype control was mixed with purified recombinant V30M TTR protein in PBS containing 0.1% sodium deoxycholate and incubated at 37 °C for 3 days. The molar ratio of V30M TTR and the antibodies was 10:0.01 to 10:2 μm. Fluorescence intensity was measured by thioflavinT assay with PHERAstar (BMG Labtech) (excitation wavelength, 440 nm; emission wavelength, 480 nm) to evaluate the degree of TTR fibrillization.

Macrophage Phagocytosis Assay

The establishment and characterization of the iPS cell-derived myeloid/macrophage line (iPS-ML) have been previously reported (32). Aggregated TTR was generated from native V30M TTR by incubating for 24 h at 37 °C under acidic conditions (pH 4.0). To investigate the clearance of antibodies against misfolded TTR, mitomycin C-treated iPS-MLs (1 × 105 cells/well) with TTRs (800 nm) were co-cultured in 200 μl of serum-free medium (Opti-MEM) supplemented with 100 ng/ml GM-CSF and 50 ng/ml M-CSF in 96-well plates. In addition, RT24 antibody (10 μl/ml) was added to the plates. After incubation for 2 days, TTR levels in each culture supernatant were measured by ELISA. Briefly, 96-well plates were coated with each culture supernatant in carbonate buffer overnight at 4 °C. The plates were blocked with coating buffer containing 0.5% gelatin for 1 h at room temperature. To detect TTRs, rabbit polyclonal anti-prealbumin and goat anti-rabbit IgG antibodies conjugated with HRP (Dako) were used for 1 h at room temperature as the primary and secondary antibodies, respectively. After incubation with SureBlueTM TMB microwell peroxidase substrate (KPL), absorbance was detected at 450 nm.

Efficacy Estimation of T24 Antibody in FAP Model Rats

Tg rats possessing a human ATTR V30M gene (ATTR V30M Tg rats) were generated as described previously (19). Each 3-month-old Tg rat received caudal intravenous injections of 10 mg/kg T24 and blood examinations every week. After 6 months, blood and tissues were collected for analysis. For quantitation of TTR deposition, paraffin-embedded 4-μm-thick sections of rat colons were stained as described. The sections were examined under a light microscopy, and the entire field of the rat colon was digitized using an Olympus DP71 camera and DP-BSW-V3.1 software at ×100 magnification. Briefly, individual images of the section were captured and then merged to produce an image of the whole colon section. The degree of amyloid deposition was determined by computer measurement of TTR-positive areas via the public domain ImageJ program developed by the National Institutes of Health and available at rsb.info.nih.gov, as described previously (33). The analysis of blood biochemistry was performed by the central clinical laboratory at Kumamoto University.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± S.D. Student's t test was used evaluating statistical significance. p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Author Contributions

A. H. and M. T. generated antibody, designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments shown in Figs. 2 and 5–8, and wrote most of the paper. Y. S. and J. G. designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments shown in Figs. 3, 4, and 10 and wrote the paper. D. I. performed the experiment shown in Fig. 7. G. S., H. M., and S. S. designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments shown in Fig. 9. A. H. and H. H. designed the antibody humanization. M. U. and T. I. conducted experiments and designed research studies. T. N., K. S., H. J., and Y. A. conducted experiments, designed research studies, and wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tomoyo Takeo and Masayo Oohori for their technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by the Adaptable and Seamless Technology Transfer Program through Target-driven R&D, Japan Science and Technology Agency, (AS2311336G), grants from the Surveys and Research on Specific Disease, the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan, Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan: (A) 24249036 and (B) 15H04841, and Challenging Exploratory Research 15K15195 (to Y. A.) and 15K15006 (to H. J.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- FAP

- familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy

- ATTR

- amyloidogenic transthyretin

- IPTG

- isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside

- TTR

- transthyretin

- RT24

- humanized T24

- LT

- liver transplantation

- CT24

- chimera T24 antibody

- Aβ

- amyloid β

- SPR

- surface plasmon resonance

- KLH

- keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- ML

- macrophage line

- CDR

- complementarity determining region

- Tg

- transgenic.

References

- 1. Glenner G. G. (1980) Amyloid deposits and amyloidosis: the β-fibrilloses (second of two parts). N. Engl. J. Med. 302, 1333–1343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Araki S., and Ando Y. (2010) Transthyretin-related familial amyloidotic polyneuropath–Progress in Kumamoto, Japan (1967–2010). Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 86, 694–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ueda M., and Ando Y. (2014) Recent advances in transthyretin amyloidosis therapy. Transl. Neurodegener. 3, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ando Y., Nakamura M., and Araki S. (2005) Transthyretin-related familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. Arch. Neurol. 62, 1057–1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hou X., Aguilar M. I., and Small D. H. (2007) Transthyretin and familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. Recent progress in understanding the molecular mechanism of neurodegeneration. FEBS J. 274, 1637–1650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jiang X., Smith C. S., Petrassi H. M., Hammarström P., White J. T., Sacchettini J. C., and Kelly J. W. (2001) An engineered transthyretin monomer that is nonamyloidogenic, unless it is partially denatured. Biochemistry 40, 11442–11452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Foss T. R., Kelker M. S., Wiseman R. L., Wilson I. A., and Kelly J. W. (2005) Kinetic stabilization of the native state by protein engineering: implications for inhibition of transthyretin amyloidogenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 347, 841–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hurshman A. R., White J. T., Powers E. T., and Kelly J. W. (2004) Transthyretin aggregation under partially denaturing conditions is a downhill polymerization. Biochemistry 43, 7365–7381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ando Y., Ando E., Tanaka Y., Yamashita T., Tashima K., Suga M., Uchino M., Negi A., and Ando M. (1996) De novo amyloid synthesis in ocular tissue in familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy after liver transplantation. Transplantation 62, 1037–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Falk R. H., and Dubrey S. W. (2010) Amyloid heart disease. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 52, 347–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Said G., Grippon S., and Kirkpatrick P. (2012) Tafamidis. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11, 185–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Coelho T., Adams D., Silva A., Lozeron P., Hawkins P. N., Mant T., Perez J., Chiesa J., Warrington S., Tranter E., Munisamy M., Falzone R., Harrop J., Cehelsky J., Bettencourt B. R., et al. (2013) Safety and efficacy of RNAi therapy for transthyretin amyloidosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 819–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goldsteins G., Persson H., Andersson K., Olofsson A., Dacklin I., Edvinsson A., Saraiva M. J., and Lundgren E. (1999) Exposure of cryptic epitopes on transthyretin only in amyloid and in amyloidogenic mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 3108–3113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kohno K., Palha J. A., Miyakawa K., Saraiva M. J., Ito S., Mabuchi T., Blaner W. S., Iijima H., Tsukahara S., Episkopou V., Gottesman M. E., Shimada K., Takahashi K., Yamamura K., and Maeda S. (1997) Analysis of amyloid deposition in a transgenic mouse model of homozygous familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. Am. J. Pathol. 150, 1497–1508 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Terazaki H., Ando Y., Fernandes R., Yamamura K., Maeda S., and Saraiva M. J. (2006) Immunization in familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy: counteracting deposition by immunization with a Y78F TTR mutant. Lab. Invest. 86, 23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gustavsson A., Engström U., and Westermark P. (1994) Mechanisms of transthyretin amyloidogenesis. Antigenic mapping of transthyretin purified from plasma and amyloid fibrils and within in situ tissue localizations. Am. J. Pathol. 144, 1301–1311 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eneqvist T., Olofsson A., Ando Y., Miyakawa T., Katsuragi S., Jass J., Lundgren E., and Sauer-Eriksson A. E. (2002) Disulfide-bond formation in the transthyretin mutant Y114C prevents amyloid fibril formation in vivo and in vitro. Biochemistry 41, 13143–13151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bergström J., Engström U., Yamashita T., Ando Y., and Westermark P. (2006) Surface exposed epitopes and structural heterogeneity of in vivo formed transthyretin amyloid fibrils. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 348, 532–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ueda M., Ando Y., Hakamata Y., Nakamura M., Yamashita T., Obayashi K., Himeno S., Inoue S., Sato Y., Kaneko T., Takamune N., Misumi S., Shoji S., Uchino M., and Kobayashi E. (2007) A transgenic rat with the human ATTR V30M: a novel tool for analyses of ATTR metabolisms. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 352, 299–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Su Y., Jono H., Torikai M., Hosoi A., Soejima K., Guo J., Tasaki M., Misumi Y., Ueda M., Shinriki S., Shono M., Obayashi K., Nakashima T., Sugawara K., and Ando Y. (2012) Antibody therapy for familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. Amyloid 19, 45–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Phay M., Blinder V., Macy S., Greene M. J., Wooliver D. C., Liu W., Planas A., Walsh D. M., Connors L. H., Primmer S. R., Planque S. A., Paul S., and O'Nuallain B. (2014) Transthyretin aggregate-specific antibodies recognize cryptic epitopes on patient-derived amyloid fibrils. Rejuvenation Res. 17, 97–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wisniewski T., and Goñi F. (2015) Immunotherapeutic approaches for Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 85, 1162–1176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lannfelt L., Relkin N. R., and Siemers E. R. (2014) Amyloid-β-directed immunotherapy for Alzheimer's disease. J. Intern. Med. 275, 284–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arsequell G., and Planas A. (2012) Methods to evaluate the inhibition of TTR fibrillogenesis induced by small ligands. Curr. Med. Chem. 19, 2343–2355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Matsubara K., Mizuguchi M., and Kawano K. (2003) Expression of a synthetic gene encoding human transthyretin in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr. Purif. 30, 55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Episkopou V., Maeda S., Nishiguchi S., Shimada K., Gaitanaris G. A., Gottesman M. E., and Robertson E. J. (1993) Disruption of the transthyretin gene results in mice with depressed levels of plasma retinol and thyroid hormone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 2375–2379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Köhler G., and Milstein C. (1975) Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature 256, 495–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yonemura H., Imamura T., Soejima K., Nakahara Y., Morikawa W., Ushio Y., Kamachi Y., Nakatake H., Sugawara K., Nakagaki T., and Nozaki C. (2004) Preparation of recombinant α-thrombin: high-level expression of recombinant human prethrombin-2 and its activation by recombinant ecarin. J. Biochem. 135, 577–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Foote J., and Winter G. (1992) Antibody framework residues affecting the conformation of the hypervariable loops. J. Mol. Biol. 224, 487–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Winter G., and Milstein C. (1991) Man-made antibodies. Nature 349, 293–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Khurana R., Coleman C., Ionescu-Zanetti C., Carter S. A., Krishna V., Grover R. K., Roy R., and Singh S. (2005) Mechanism of thioflavin T binding to amyloid fibrils. J. Struct. Biol. 151, 229–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Haruta M., Tomita Y., Yuno A., Matsumura K., Ikeda T., Takamatsu K., Haga E., Koba C., Nishimura Y., and Senju S. (2013) TAP-deficient human iPS cell-derived myeloid cell lines as unlimited cell source for dendritic cell-like antigen-presenting cells. Gene Ther. 20, 504–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ueda M., Ando Y., Nakamura M., Yamashita T., Himeno S., Kim J., Sun X., Saito S., Tateishi T., Bergström J., and Uchino M. (2006) FK506 inhibits murine AA amyloidosis: possible involvement of T cells in amyloidogenesis. J. Rheumatol. 33, 2260–2270 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]