Abstract

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is the most rapidly growing form of liver disease and if left untreated can result in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, ultimately resulting in liver cirrhosis and failure. Biliverdin reductase A (BVRA) is a multifunctioning protein primarily responsible for the reduction of biliverdin to bilirubin. Also, BVRA functions as a kinase and transcription factor, regulating several cellular functions. We report here that liver BVRA protects against hepatic steatosis by inhibiting glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) by enhancing serine 9 phosphorylation, which inhibits its activity. We show that GSK3β phosphorylates serine 73 (Ser(P)73) of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα), which in turn increased ubiquitination and protein turnover, as well as decreased activity. Interestingly, liver-specific BVRA KO mice had increased GSK3β activity and Ser(P)73 of PPARα, which resulted in decreased PPARα protein and activity. Furthermore, the liver-specific BVRA KO mice exhibited increased plasma glucose and insulin levels and decreased glycogen storage, which may be due to the manifestation of hepatic steatosis observed in the mice. These findings reveal a novel BVRA-GSKβ-PPARα axis that regulates hepatic lipid metabolism and may provide unique targets for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Keywords: glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3), heme oxygenase, liver metabolism, nuclear receptor, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)

Introduction

Obesity is a worldwide epidemic that may be due to either genetic factors or by overeating and a sedentary lifestyle. During adipose tissue expansion, the number of adipocytes increase, as well as plasma glucose and fatty acid levels. During times of fasting, adipocytes release more fatty acids by lipolysis, which are shuffled to the liver and either produced into sugars from gluconeogenesis or stored as lipids (1). Long term obesity causes an overload of lipids in the liver, and fatty acid peroxidation, causing increased reactive oxygenase species and infiltration of immune cells. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)3 is characterized by hepatic fat accumulation that, when coupled with another “hit,” such as increased oxidative stress, inflammation, or insulin resistance, can lead to the progression of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (2). However, hepatic steatosis may only represent the initial phase of several distinct injurious pathways rather than a true hit. Given this possibility, the initial “two-hit” theory for explaining the progression from NAFLD to NASH is now being modified to a “multiple parallel hits” hypothesis (3). In the multiple-hit model, the first hit is insulin resistance and associated metabolic disturbances, such as alterations in adipose tissue lipolysis increasing the efflux of free fatty acids from adipose to liver. The increase in free fatty acid delivery to the liver leads to hepatic steatosis, which causes the liver to be vulnerable to any hit that may follow, including increased oxidative stress and inflammation, thereby leading to hepatocyte injury and progression to NASH, liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and ultimately liver failure. Factors that regulate insulin sensitivity, as well as reduce oxidative stress, minimize the capacity of immune signaling during hepatic lipid accumulation and prevent liver injury. We recently showed that induction of the heme oxygenase system and production of the antioxidant, bilirubin, reduced hepatic steatosis and lowered blood glucose (4).

The catabolism of heme from heme oxygenase produces biliverdin, which is reduced to bilirubin by biliverdin reductase (BVR), which exists as two isozymes: BVRA and BVRB (5). BVRB is the fetal isoform responsible for the production of bilirubin IXβ from biliverdin IXβ (6) and is only produced during the first 20 weeks after gestation. BVRB is expressed in adult tissues, but little is known about its function after fetal production of biliverdin IXβ has discontinued. The BVRA isoform is also expressed in adult tissues and is responsible for reducing biliverdin IXα to bilirubin IXα. In addition to functioning as a biliverdin reductase, BVRA can also function as a kinase and transcription factor and modulate insulin receptor signaling (5, 7). Despite the multiple functions of BVRA and bilirubin their roles, in protecting the liver from hepatic steatosis have yet to be established. We recently showed that BVRA-derived bilirubin IXα binds directly to the nuclear receptor transcription factor PPARα to reduce adiposity and blood glucose (8). This is the first known ligand function reported for bilirubin. Importantly, PPARα expression (4, 9, 10) and bilirubin levels are decreased in the obese (4, 9–11). The main function of PPARα is to reduce hepatic steatosis through the burning of fatty acids via the regulation of genes involved in the β-oxidation pathway. The activation of PPARα has been demonstrated to play a significant role in the attenuation of hepatic steatosis (14–16). PPARα is a phosphoprotein; however, the regulation of the protein by phosphorylation by specific kinases and phosphatases are largely unknown (17). However, PPARγ, which induces fat storage in adipocytes and liver, has been shown to be regulated by kinases (18) and at least one phosphatase (19). Indeed, PPARγ induces hepatic steatosis (20). The mediation of lipid and glycogen storage in the liver is a delicate balance of kinase and phosphatase signaling during fasting and refeeding, as well as in lipid overload in fatty liver development. One of the major kinases involved in the progression of fatty liver is glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), which inhibits glycogen storage by the inhibition of glycogen synthase 2 via phosphorylation of the protein (21, 22). GSK3β activation plays a significant role in hepatic lipid accumulation and lipoapoptosis (23, 24). Regulation of GSK3β activity primarily occurs through phosphorylation at serine 9 of the protein, and increased phosphorylation of GSK3β at this residue decreases kinase activity.

In this study, we show in vitro and in vivo that hepatic BVRA can preserve PPARα activity by increasing the phosphorylation of serine 9 in GSK3β. Furthermore, we show that GSK3β can increase phosphorylation of serine 73 in PPARα, which causes rapid protein turnover and decreased overall PPARα activity. Our data show a relationship between BVRA, GSK3β, and PPARα in the regulation of hepatic lipid metabolism and opens new avenues for therapeutic targeting.

Results

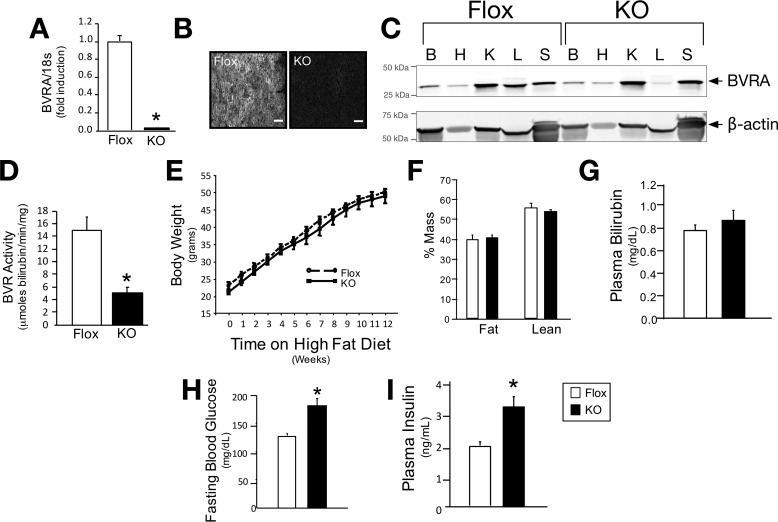

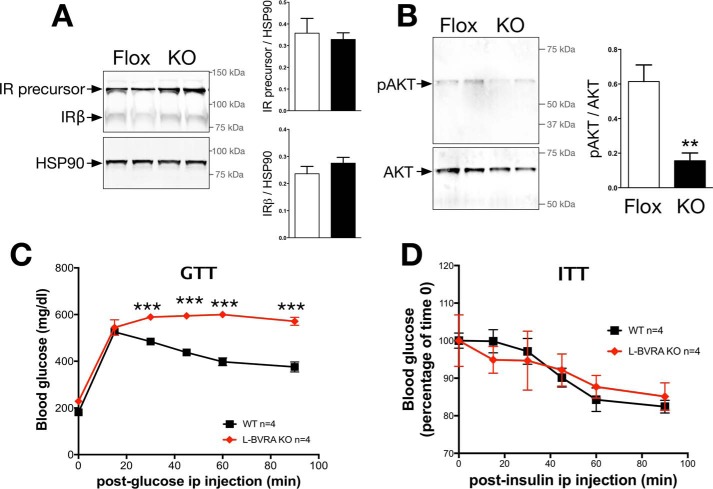

Liver-specific Deletion of BVRA Reduces Hepatic Insulin Signaling

BVRA is an important protein regulating insulin signaling (5, 7, 25) and directly binds to and enhances phosphorylation of AKT (5) and ERK (26). The capacity of BVRA to regulate insulin signaling suggests a role in the management of diabetes; however, BVRA, to date, has not been studied in whole animals. We generated floxed BVRA mice and after crossing them to Alb-cre (B6.Cg-Tg(Alb-cre)21Mgn/J) mice, LBVRA-KO mice were developed (described in detail under “Experimental Procedures”). LBVRA-KO mice display decreased levels of BVRA mRNA and protein (Fig. 1, A–C), as well as significantly (p < 0.05) less BVR activity in the liver (Fig. 1D). After LBVRA-KO mice were placed on a high fat diet, no differences in body weight, body composition, or plasma bilirubin levels were observed between the LBVRA-KO and flox control mice (Fig. 1, E–G). However, LBVRA-KO mice exhibited enhanced fasting hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia as compared with flox control mice (Fig. 1, H and I). Examination of insulin signaling pathways in the liver of LBVRA-KO found no differences in the levels of insulin receptor-β (IRβ) or the IR precursor (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, the levels of AKT phosphorylation (pAKT) were markedly decreased in LVBRA-KO livers compared with flox mice (Fig. 2B). LBVRA-KO mice exhibited an alteration in the glucose but not insulin tolerance test as compared with flox mice (Fig. 2, C and D). These results suggest that a liver-specific loss of BVRA promotes hepatic insulin resistance that, in turn, leads to increased plasma glucose and insulin levels, which most likely stemmed from reduced insulin signaling and not insulin receptor expression.

FIGURE 1.

Liver-specific knock-out of BVRA in mice increases blood glucose. A, real time PCR of BVRA in the liver of LBVRA KO and flox mice. B, hepatic immunofluorescence staining for BVRA. Scale bars, 75 μm. C, Western blot of BVRA from different tissues. B, brain; H, heart; K, kidney; L, liver; S, spleen. D, hepatic BVR activity. E–I, measurement of body weight (E), lean and fat mass (F), as well as plasma bilirubin (G), glucose (H), and insulin (I) in LBVRA KO and control flox mice. *, p < 0.05 (versus floxed mice; ± S.E.; n = 6–8/group).

FIGURE 2.

BVRA regulates hepatic insulin signaling. A and B, Western blot and densitometry of the insulin receptor precursor and insulin receptor-β (IRβ) in the liver (A) or AKT1/2 and phosphorylated AKT in the liver (B). C, GTT. D, ITT in LBVRA KO and control flox mice. **, p < 0.01 (versus flox mice; ± S.E.; n = 4); ***, p < 0.001 (versus flox mice; ± S.E.; n = 4).

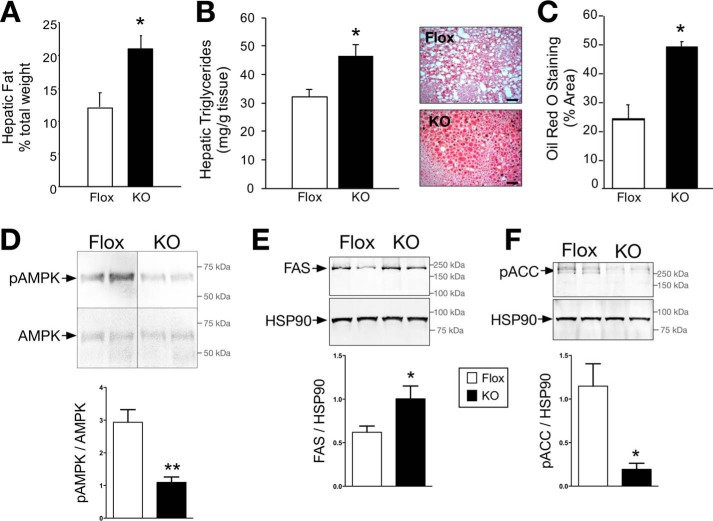

BVRA Regulates Hepatic Lipid Accumulation

The accumulation of lipids in the liver and the development of fatty liver lead to decreased hepatic insulin sensitivity, which affects whole body insulin turnover, thereby increasing systemic levels of insulin and glucose. High circulating insulin levels may also cause peripheral insulin resistance and glucose intolerance. Hepatic lipid accumulation in the LBVRA-KO and floxed mice was determined by Echo-MRI, hepatic triglyceride levels, and Oil Red O staining of tissues slices. Livers from LBVRA-KO mice had significantly (p < 0.05) higher lipid levels compared with flox mice as shown by liver weight, hepatic triglycerides, and Oil Red O staining (Fig. 3, A–C). Several studies show increased phosphorylated AMP-activated protein kinase signaling is protective against hepatic steatosis. AMPK is activated by a decrease in ATP and a rise in cellular AMP (27–29), which lead to the phosphorylation of key enzymes that subsequently inhibit the synthesis of fatty acids and increase glucose uptake. Levels of phosphorylated AMPK were markedly decreased in LBVRA-KO mice compared with flox mice (Fig. 3D). Development of hepatic steatosis is linked to de novo production of fatty acids controlled by fatty acid synthase (FAS) and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC). FAS is responsible for the production of long chain fatty acids that contribute to the triglyceride pool. Parallel with lipid accumulation, FAS was significantly increased in the liver of LBVRA-KO mice as compared with flox mice (Fig. 3E). Similarly, LBVRA-KO mice exhibited a significant reduction in the levels of phosphorylated ACC (Fig. 3F), which indicates enhanced ACC activity. ACC catalyzes the first steps of lipid synthesis involving the carboxylation of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA. These data demonstrate that the loss of hepatic BVRA resulted in an enhancement of proteins and signaling pathways involved in the synthesis of fatty acids, which contributed to hepatic steatosis.

FIGURE 3.

The loss of hepatic BVRA causes lipid accumulation. A, hepatic fat measured by Echo-MRI. B, biochemical measurement of hepatic triglyceride levels. C, Oil Red O staining of liver sections and densitometry. Scale bars, 50 μm. D–F, representative Western blot of hepatic expression of AMPK and phosphorylated AMPK (D), FAS (E), and phosphorylated ACC (F). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 (versus flox mice; ± S.E.; n = 4).

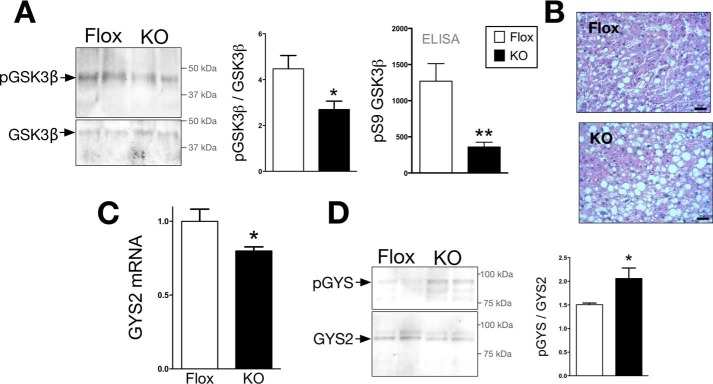

BVRA Regulates GSK3β and Hepatic Glycogen Storage

Glycogen synthase is the key enzyme involved in the storage of glucose as glycogen in liver and muscle. Glycogen synthase 2 (GYS2) is the predominant isoform found in the liver that is responsible for glycogen production. Phosphorylation at serine 641 by GSK3β inhibits activity of GYS2 and causes decreased glycogen storage (21, 22). Conversely, for glycogen storage, GSK3β is inhibited by phosphorylation of serine 9. GSK3β phosphorylation was measured by two methods: Western blotting and a phosphoserine 9 GSK3β-specific ELISA. The levels of serine 9 phosphorylated GSK3β were significantly decreased in the liver of LBVRA-KO as compared with flox control mice (Fig. 4A), which indicates activation. The increased GSK3β activity in LBVRA-KO mice is supported by decreased liver glycogen stores, GYS2 mRNA, and increased levels of phosphorylated GYS2 when compared with flox mice (Fig. 4, B–D). These data demonstrate that BVRA decreases GSK3β activity to enhance glycogen storage.

FIGURE 4.

GSK3β is more active in the LBVRA KO mice and suppresses glycogen storage. A and B, Western blot and densitometry of hepatic total and phosphorylated GSK3β and levels of serine 9 phosphorylated (pS9) GSK3β measured by ELISA (A) and periodic acid Schiff staining for glycogen in liver (B). Scale bars, 50 μm. C, real time PCR measurement of hepatic expression levels of GYS2 mRNA. D, representative Western blot of hepatic GYS2 and serine 641 phosphorylation of GYS. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 (versus flox mice; ± S.E.; n = 4).

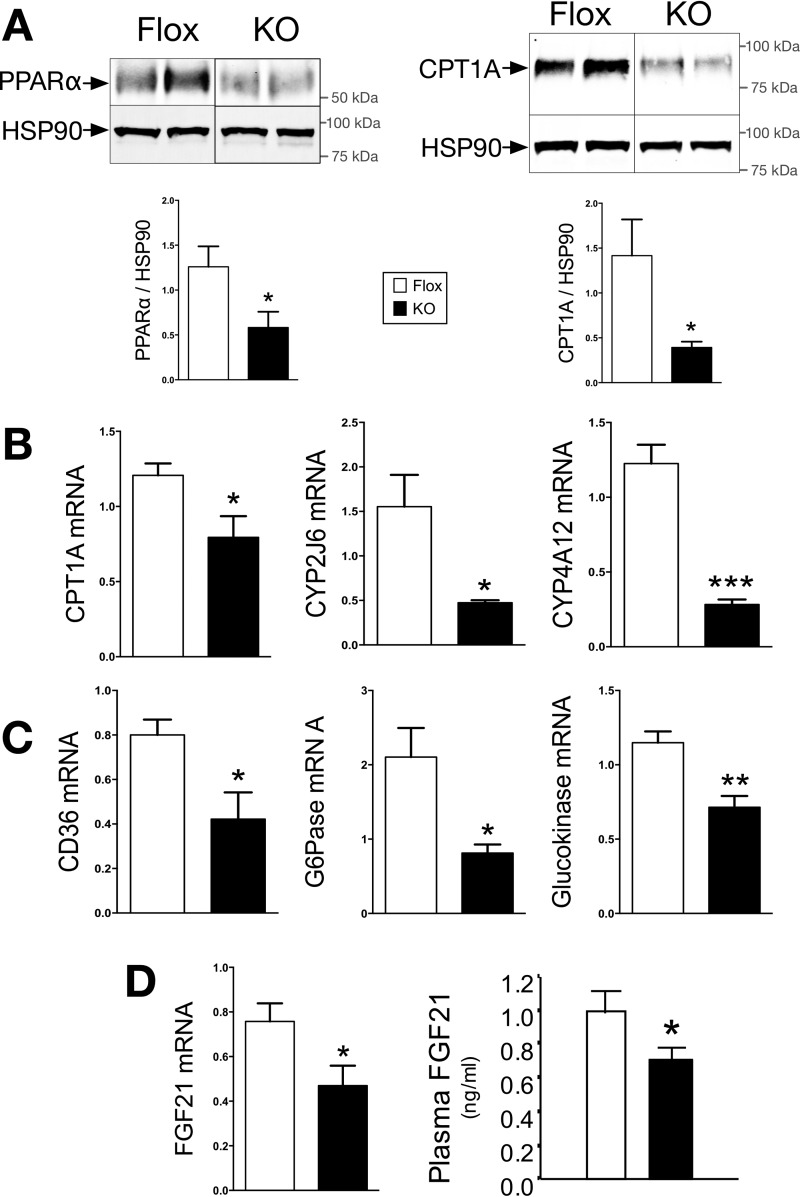

BVRA Regulates PPARα Expression and Activity in the Liver

Hepatic steatosis arises from increased synthesis of fatty acids or by decreasing the burning of fat (β-oxidation). PPARα also binds to the promoter of GYS2 to increase expression (30), which together interacts to regulate glycogen storage and steatosis. PPARα regulation of lipid accumulation derives mainly from carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1A (CPT1A) and fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21). CPT1A is the rate-limiting enzyme in mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation. PPARα, and regulated gene CPT1A, protein levels were significantly (p < 0.05) decreased in the liver of LBVRA-KO as compared with flox mice (Fig. 5, A and B). The reduction in PPARα activity was confirmed by examining the expression of several of its target genes in the liver (Fig. 5, B and C). FGF21, a major PPARα target gene whose hepatic expression and plasma levels were also significantly decreased in LBVRA-KO as compared with flox mice (Fig. 5D). These data show that BVRA is a major regulator of β-oxidation by mediating PPARα expression and activity.

FIGURE 5.

PPARα expression and activity are reduced in LBVRA KO mice. A and B, Western blot and densitometry of hepatic protein levels of CPT1A and PPARα (A), and real time PCR of CPT1A, CYP2J6, and CYP4A12 mRNA (B). C, real time PCR of CD36, G6Pase, and glucokinase mRNA. D, real time PCR of FGF21 mRNA and plasma FGF21 level in LBVRA KO and control flox mice. *, p < 0.05 (versus flox mice; ± S.E.; n = 4).

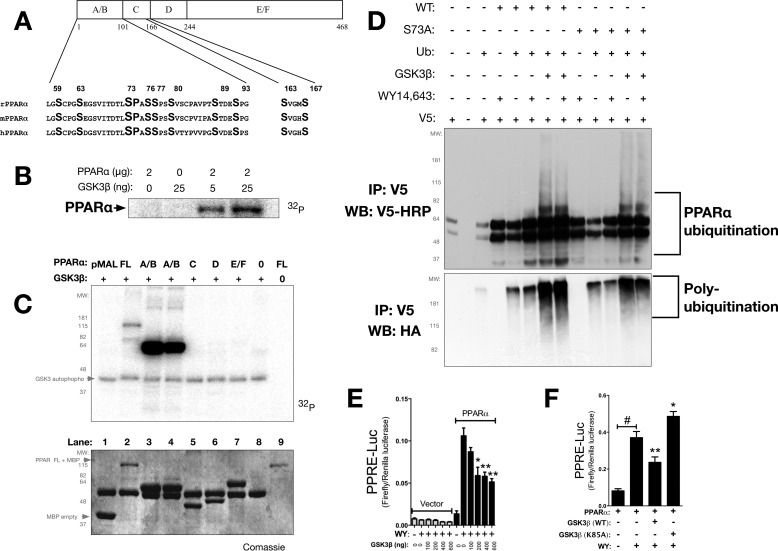

GSK3β Regulates PPARα Activity Predominately through Phosphorylation of Serine 73

To determine the effect of GSK3β on PPARα expression and activity, we examined a series of experiments utilizing kinase assays, ubiquitination, and the minimal PPRE-3tk-Luc construct. PPARα has four major structural domains, the A/B (activation factor), C (DNA binding domain), D, and E/F (ligand binding) domains, that harbor five potential GSK3 phosphorylation sites (serines 59, 73, 76, 89, and 163) that are conserved across mammalian species (Fig. 6A). In vitro kinase assays showed that GSK3β, based on kinase level, directly phosphorylates PPARα (Fig. 6B). To localize the sites within PPARα directly phosphorylated by GSK3β, in vitro kinase assays were performed with purified PPARα domain proteins (Fig. 6C). Full-length PPARα was a substrate for phosphorylation by GSK3β; however, the A/B domain of PPARα was a better substrate for GSK3β phosphorylation in this assay (Fig. 6C). No phosphorylation occurred in the C-domain, despite the fact that it contains a consensus GSK3 binding site. Furthermore, no phosphorylation was observed in the D and E/F domains of the PPARα protein. Mutational analysis of serine S59A, S73A, S76A, and S89A in the PPARα protein revealed that serine 73 (Ser73) was the primary site in the A/B domain phosphorylated by GSK3β (data not shown). To determine whether GSK3β mediates ubiquitination of PPARα protein by increasing Ser73 phosphorylation, we performed transfections with WT PPARα or S73A PPARα in the presence of GSK3β, ubiquitin, or empty vector. The cells were treated with DMSO or WY-14643 in the presence of, MG132, a proteasome inhibitor. The co-expression of PPARα and GSK3β dramatically increased the ubiquitination of PPARα relative to receptor alone (Fig. 6D). A ligand-dependent increase in ubiquitination was observed with receptor alone (fifth and sixth lanes), but no appreciable difference in ligand-dependent ubiquitination was observed with the overexpression of GSK3β (seventh and eighth lanes). The overexpression of GSK3β with S73A PPARα resulted in increased ubiquitination (tenth and eleventh lanes), but decreased ubiquitination of S73A PPARα was seen relative to WT receptor (twelfth and thirteenth lanes) (Fig. 6D). To determine whether GSK3β mediates PPARα activity, we overexpressed GSK3β in a concentration-dependent manner and measured PPARα-dependent activation of the minimal PPRE promoter luciferase activity (PPRE-3tk-luc). Increasing concentrations of GSK3β decreased PPARα activation with ligand, which was not observed in the empty vector control (Fig. 6E). However, a K85A kinase-dead mutation of GSK3β failed to attenuate PPARα-dependent activation of the PPRE promoter luciferase activity (Fig. 6F). Altogether, these data demonstrate that GSK3β affects the ubiquitination of PPARα by increasing phosphorylation of Ser73 in PPARα, which ultimately inhibits activity.

FIGURE 6.

GSK3β targets PPARα by phosphorylation at serine 73 for degradation. A, graphical representation of serines in the activation factor-1 A/B domains of rat (rPPARα), mouse (mPPARα), and human (hPPARα). PPARα contains five putative GSK3 consensus phosphorylation sites within the A/B and C domains. B, purified bacterially expressed pMAL-PPARα wild-type was incubated with [γ-32P]ATP in the presence of increasing amounts of activated GSK3β. C, purified bacterially expressed pMAL-PPARα full-length (FL) and domains (A/B, C, D, and E/F) were incubated with [γ-32P]ATP in the presence (+) or absence (−) of activated GSK3β (top panel). A Coomassie stain of the in vitro kinase assay was performed (bottom panel; representative of three or more experiments). D, Cos-1 cells were transfected with an HA-tagged ubiquitin expression vector, V5-rPPARα, V5-PPARα S73A, and/or pcDNA GSK3β. The cells were co-treated with vehicle or 50 μm WY-14643 and 5 μm MG132 for 4 h. PPARα protein was immunoprecipitated (IP) and analyzed by Western blotting (WB) using anti-V5 and anti-HA antibodies (representative of three experiments). E, PPARα activity at the minimal promoter PPRE-3tk-luc with increasing doses of GSK3β (0, 100, 200, 400, and 600 ng) with empty vector (100 ng) or PPARα (100 ng) in the presence of vehicle (WY −) or WY-14643 (WY +). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 (versus WY −, 0 GSK3β, PPARα control; ± S.E.; n = 4). PPARα and GSK3β WT and K85A mutant with the minimal promoter PPRE-3tk-luc were transfected in Cos-7 and treated with WY-14643 or vehicle for 24 h. F, PPARα activity at the minimal promoter PPRE-3tk-luc with WT GSK3β or kinase-dead K85A GSK3β in the presences of vehicle (WY −) or WY-14643 (WY +). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 (versus WY +, − GSK3β, + PPARα; ± S.E.; n = 4).

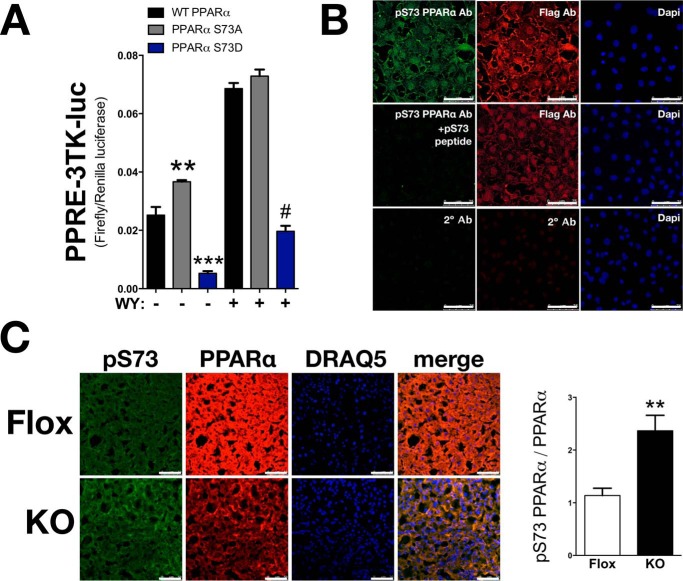

LBVRAKO Mice Have Decreased PPARα Expression and Enhanced Serine 73 Phosphorylation in the Liver

To determine the role of serine 73 phosphorylation on PPARα activity, we examined S73A PPARα, which should be resistant to GSK3β-mediated phosphorylation. In addition, a serine to aspartic acid S73D PPARα mutation was created to mimic constitutive GSK3β-mediated phosphorylation. S73A PPARα had significantly (p < 0.01) higher basal activity as compared with WT PPARα (Fig. 7A). However, no difference was observed with WY-14643-induced PPARα activity. In contrast, S73D PPARα, that mimics hyperphosphorylation by GSK3β resulted in decreased basal and WY-14643-mediated activation of PPARα activity (Fig. 7A). To detect serine 73 phosphorylation of PPARα, a rabbit phospho-specific antibody (Ser(P)73 PPARα-Ab) was generated. Specificity of Ser(P)73 PPARα-Ab was determined by transfecting COS-7 cells with FLAG-tagged PPARα, followed by immunostaining with Ser(P)73 PPARα-Ab and FLAG antibodies. As predicted, Ser(P)73 PPARα-Ab detected PPARα WT but showed no reactivity when blocked with the Ser(P)73 peptide used to create the antibody (Fig. 7B). Levels of phosphorylated serine 73 were determined in the liver of LBVRA-KO and flox mice using the Ser(P)73 PPARα specific antibody. The ratio of phosphorylated serine 73 to total PPARα immunostaining significantly (p < 0.01) increased in LBVRA-KO mice as compared with flox mice (Fig. 7C). The increase in phosphorylated Ser73 PPARα is consistent with decreased phosphorylation of Ser9 GSK3β in the liver of LBVRA-KO mice. These data also demonstrate, for the first time, that BVRA regulates GSK3β-mediated phosphorylation of PPARα, which significantly contributes to the control of hepatic lipid metabolism.

FIGURE 7.

PPARα serine 73 phosphorylation is increased in LBVRA KO mice. A, PPARα WT, S73A, and S73D mutants with the minimal promoter PPRE-3tk-luc were transfected in Cos-7 and treated with WY-14643 or vehicle for 24 h. B, COS-7 cells were transfected with a FLAG-tagged PPARα construct for 24 h followed by immunostaining with antibodies to Ser(P)73 PPARα-Ab or FLAG or with Ser(P)73 PPARα-Ab plus blocking peptide used to construct the antibody, as well as negative control with only secondary antibodies. Scale bars, 75 μm. C, levels of phosphorylated serine 73 (green), total PPARα (red), and nuclear staining (blue) with DRAQ5 in the liver of LBVRA KO and flox mice. Scale bars, 50 μm. **, p < 0.01 (versus floxed mice; ± S.E.; n = 4).

Discussion

We report here, for the first time, a new hepatic signaling paradigm for BVRA, which regulates steatosis by inhibition of GSK3β and activation of PPARα. There is insufficient knowledge of the role of BVRA in the regulation of hepatic lipid accumulation or in insulin signaling. However, the interaction between BVRA and AKT has been previously reported. The Maines laboratory (25) demonstrated BVRA mediates insulin signaling and glucose uptake in human skeletal muscle cells. Other studies indicate suppression of BVRA by siRNA decreased pAKT in HK-2 proximal tubule epithelial human cells (31) and rat heart H9c2 cells (32), suggesting that BVRA may positively affect glucose uptake. In this study, we show that the LBVRA-KO mice had significantly reduced phosphorylation of AKT in the liver and higher plasma glucose and insulin levels. LBVRA-KO mice also exhibited alterations in glucose tolerance tests (GTTs) but not insulin tolerance tests (ITTs), suggesting alterations in hepatic insulin sensitivity. Interestingly, the body weight, fat and lean mass, and plasma bilirubin levels were the same as observed in the floxed mice. However, the LBVRA-KO mice had more lipids in the liver. Lipid accumulation in the liver leads to hepatic insulin resistance that can manifest into peripheral insulin resistance and eventually non-insulin dependent type II diabetes mellitus. The increased expression of FAS and phosphorylated ACC in the LBVRA-KO mice, which are involved in fatty acid synthesis, correlates with the development of hepatic steatosis in response to high fat diet feeding. FAS can generate lipids that can act as intracellular signaling molecules that are capable of regulating genes involved in the oxidation of fatty acids and fat storage. ACC is the rate-liming enzyme that catalyzes lipids for synthesis involving the carboxylation of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA, which is then used for the storage of fat. ACC activity is inhibited via phosphorylation by AMPK, which, along with PPARα, increases the burning of fat through the β-oxidation pathway. The phosphorylation of ACC and AMPK was significantly reduced in LBVRA KO mice, indicating reduced burning of fat through β-oxidation. PPARα increases key regulators of β-oxidation, CPT1 and FGF21, which CPT1 binds to long chain fatty acids in the mitochondria for lipid metabolism. FGF21 is a hepatic hormone that decreases fat in liver and increases glucose uptake (4, 33–36). Indeed, the LBVRA-KO mice exhibited reduced levels of hepatic CPT1A and FGF21. Other PPARα target genes GYS2, CD36, G6Pase, glucokinase, CYP2J6, and CYP4A12 were significantly reduced in the livers of the LBVRA-KO mice. Overall, the loss of hepatic BVRA resulted in a decrease in the pathway for fatty acid oxidation and glycogen storage, as well as an increase in fatty acid synthesis and marked hepatic steatosis that most likely contributed to the increased blood glucose and insulin levels.

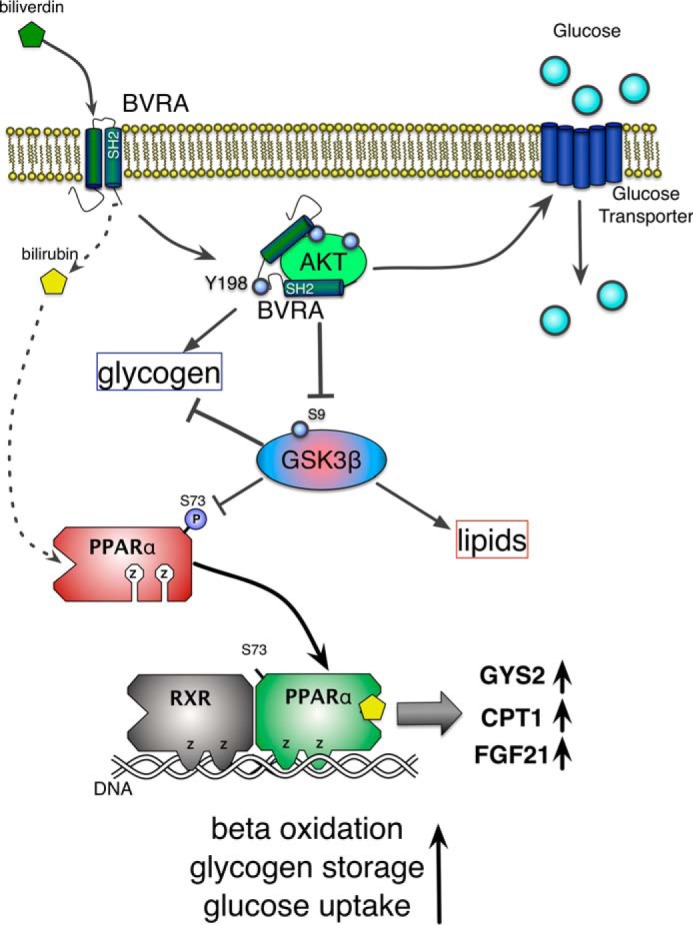

Our study identifies a novel pathway by which BVRA can regulate hepatic PPARα levels through the modulation of GSK3β-mediated phosphorylation of Ser(P)73. BVRA has been recently shown to directly interact with GSK3β (37). Our data demonstrate that BVRA prevents GSK3β phosphorylation of PPARα at serine 73 to decrease ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the protein. GSK3β is implicated in fatty liver disease and apoptosis, and small molecule inhibitors of GSK3β are demonstrated to protect against obesity-induced hepatic steatosis (38–41). LBVRA-KO mice have lower GSK3β phosphorylation, which is indicative of kinase activation (21, 42). GSK3β activation was also evident by the enhanced phosphorylation of GYS2 in the liver of LBVRA-KO mice. Interestingly, the LBVRA-KO mice also had enhanced phosphorylation of serine 73 in PPARα, as well as decreased PPARα expression and activity. We show that the decline in PPARα activity and expression was mediated by GSK3β, which was most likely to reduce β-oxidation and glycogen storage pathways. The importance of Ser(P)73 in PPARα regulation is further established by our findings that a mutation of this serine residue to an alanine is resistant to GSK3β-mediated phosphorylation and decreased the activity of the protein. In contrast, mutation of this residue to aspartic acid to mimic GSK3β-mediated phosphorylation resulted in decreased PPARα activity under basal conditions and response to WY-14643 treatment. Taken together, these data identify Ser(P)73 of PPARα as a GSK3β target that is inhibited by hepatic BVRA to regulate fatty acid metabolism in liver and enhance PPARα-mediated gene transcription of the β-oxidation pathway (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

Diagram of hepatic BVRA signaling to reduce fatty liver and increase glycogen storage. BVRA reduces biliverdin to bilirubin, which binds to and activates the nuclear receptor PPARα for the burning of fat by β-oxidation and storage of glycogen by increasing GYS2. Additionally, BVRA binds directly to AKT to increase phosphorylation, which inhibits GSK3β activity to increase glycogen and decrease lipid storage in the liver. The BVRA-AKT interaction also increases hepatic insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake.

Although we have identified a novel pathway by which BVRA can decrease hepatic steatosis via inhibition of GSK3β mediated phosphorylation of PPARα, this pathway may also impact lipid accumulation through the intracellular production of bilirubin. Bilirubin is a powerful antioxidant molecule (43, 44). In addition to being a potent antioxidant, bilirubin has anti-inflammatory properties and can serve to prevent other types of cell stressors, such as endoplasmatic reticulum stress (25–27). Several studies demonstrate increased serum bilirubin levels are associated with decreased hepatic steatosis (45–47). Despite these correlative studies, which show a protective effect of serum bilirubin on hepatic steatosis, the mechanism by which bilirubin offers this safeguard is not currently known. However, we recently identified bilirubin as a novel PPARα agonist (8). Interestingly, its precursor, biliverdin, does not bind PPARα efficiently (8). Acute treatment of mice with bilirubin resulted in an increased hepatic PPARα target genes, including FGF21, which was not observed in the liver or plasma of PPARα knock-out mice (8). Our results here demonstrate that hepatocyte-specific deletion of BVRA decreases PPARα activity in the liver through alterations in GSK3β activity; however, the loss of bilirubin-derived PPARα signaling increased hepatic steatosis in mice fed a high fat diet cannot be ruled out. However, BVRA has a 2-fold protection mechanism against NAFLD and fatty liver disease: 1) production of bilirubin that functions as an antioxidant and PPARα ligand and 2) BVRA activation of AKT and inhibition of GSK3β (Fig. 8). The degree to which the loss of bilirubin production contributes to this phenotype will need to be examined in future studies.

In conclusion, NAFLD, caused by the high rate of obesity, is the most rapidly growing form of liver disease in the general population. Currently, there are no effective treatments for NAFLD, and if combined with an additional hit to the liver, it can progress to NASH and ultimately liver failure. We have identified a novel pathway by which BVRA regulates hepatic steatosis by regulating GSK3β-mediated phosphorylation of Ser(P)73 of PPARα, which increases protein degradation and loss of PPARα signaling. Our results suggest that hepatic BVRA or BVRA-mediated bilirubin will increase the burning of fat and sensitization to insulin and glucose intolerance. The BVRA-AKT-PPARα axis is a major signaling paradigm, preventing fatty liver disease and insulin resistance.

Experimental Procedures

Animals

The experimental procedures and protocols of this study conform to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Mississippi Medical Center in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All mice had free access to food and water ad libitum. Animal activity and grooming were monitored daily to assess overall animal health. The animals were housed in a temperature-controlled environment with 12 h dark-light cycle. BVRA conditional knock-out mice were generated from gene targeted embryonic stem cells purchased from the European Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis Program (EUCOMM, clone HEPD0510_3_B01) and injected into blastocysts. The stem cells contained an altered copy of the BVRA gene, in which exon 2 was flanked by loxP sites. The neomyocin/lacZ cassette was then removed by breeding to Flp (B6.Cg-Tg(Pgk1-FLPo)10Sykr/J) mice for one generation. The resulting offspring were then genotyped to confirm removal of the neo/lacZ cassette and backcrossed to C57BL/6J mice for four generations before being bred to homozygosity for the floxed BVRA allele. The floxed BVRA mice were crossed to mice expressing the Cre recombinase (B6.Cg-Tg(Alb-cre)21Mgn/J) specifically in the liver under the control of the albumin promoter (stock no. 003574; Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor ME) to create liver-specific BVRA knock-out mice (LBVRAKO). The studies were performed on 6-week-old male mice initially housed under standard conditions with full access to standard mouse chow and water. After this time, the mice were switched with full access to a 60% high fat diet (diet no. D12492; Research Diets, Inc., New Brunswick, NJ) for 12 weeks and allowed access to water.

Body and Liver Composition

Body composition changes were assessed at 4-week intervals throughout the study using magnetic resonance imaging (EchoMRI-900TM; Echo Medical System, Houston, TX). MRI measurements were performed in conscious mice placed in a thin-walled plastic cylinder with a cylindrical plastic insert added to limit movement of the mice. The mice were briefly submitted to a low intensity electromagnetic field where fat mass, lean mass, free water, and total water were measured. At the end of the experimental protocol, the mice were euthanized by overdose of isoflurane anesthesia; the liver and fat were removed, and fat and lean mass were measured.

Glucose and Insulin Tolerance Tests

For GTTs, the mice were subjected to fasting (∼8 h), and d-glucose (1 g/kg of body weight) was injected intraperitoneally. ITTs were conducted on fasted mice, and insulin (0.75 units/kg of body weight; Novolin human insulin) was injected intraperitoneally. Blood glucose was monitored at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 90 min after glucose or insulin injection.

Liver Triglyceride Measurement

Triglycerides were measured from 100 mg of liver tissue homogenized in 1 ml of 5% Nonidet P-40 in water. Homogenized tissues were then heated to 95 °C for 5 min and then centrifuged (13,000 × g) for 2 min. Tissue triglyceride levels were measured using a fluorometric assay kit according to the manufacturer's guidelines (PicoProbe triglyceride fluorometric assay kit; BioVision, Milpitas, CA). Tissue triglyceride levels were then normalized to the amount of starting tissues and expressed as mg of triglyceride/g of tissue weight. Samples from individual mice were run in duplicate and averaged, and the averages of individual mice were then used to obtain group averages.

Measurement of Hepatic Ser(P)9 GSK3β

Hepatic levels of Ser(P)9 GSK3β were measured using a specific Ser(P)9 ELISA kit according to the manufacturer's guidelines (Ser(P)9; GSK3β ELISA kit; Enzo, Farmingdale, NY). Briefly, 50 mg of liver tissue was homogenized in 500 μl of RIPA buffer supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors. Homogenates were then centrifuged briefly, and the supernatants were collected. ELISA was performed on diluted supernatants according to the manufacturer's protocols. Samples from individual mice were run in duplicate and averaged, and the averages of individual mice were then used to obtain group averages.

Measurement of Plasma FGF21

Plasma levels of FGF21 were measured from 50 μl of plasma using a specific mouse/rat FGF21 ELISA (quantikine ELISA; R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The FGF21 ELISA was calibrated with a standard curve derived from a mouse/rat FGF21 standard provided by the manufacturer. FGF21 levels were measured in duplicate from individual mice, and FGF21 levels were determined by measurement at 450 nm on a plate reader. The concentrations are expressed as ng/ml.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence for BVRA was performed on paraformaldehyde-fixed liver samples. Sections of liver (20 μm) were cut, rinsed in PBS, and blocked in 5% normal donkey serum for 1 h at 4 °C. The sections were then incubated with BVRA antibody in 5% normal donkey serum overnight at 4 °C and then rinsed in PBS. BVRA was detected using a rabbit anti-BVRA antibody (ADI-OSA-450, 1:100; Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY). Antibody labeling was visualized using a fluorescence-labeled donkey anti-rabbit Alexa 488 (A-21206, 1:1000; Invitrogen) secondary antibody. Following a final rinse in PBS and DAPI counterstaining, the samples were covered with Fluoromount-G mounting medium (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) and coverslipped before imaging. All samples were examined using a Leica TCS SP5 laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL).

Liver Oil Red O Staining

To determine the effects of treatment on hepatic lipid accumulation, the livers were mounted and frozen in Tissue-Tek O.C.T and sectioned at 10 μm. Frozen sections were air-dried and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. The sections were briefly rinsed in tap water followed by 60% isopropanol and stained for 15 min in Oil Red O solution. The sections were further rinsed in 60% isopropanol, and the nuclei were stained with hematoxylin followed by aqueous mounting and coverslipping. The degree of Oil Red O staining was determined at 40× magnification using a color Axiocam 105 camera with Zen 2 software attached to a Zeiss Axioplan microscope. The images were analyzed using National Institutes of Health ImageJ software, and to ensure accuracy of measurement, six images of each animal were analyzed and averaged into a single measurement. The measurements were obtained from three individual animals/group. The data are presented as the averages ± S.E. of the percentage of Oil Red O staining for each group.

Periodic Acid Schiff Staining for Glycogen

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded liver sections were cut at 5 μm and deparaffinized, followed by hydration. The sections were oxidized in 0.5% periodic acid solution for 5 min, rinsed in distilled water, and stained in Schiff's reagent for 15 min. The sections were washed in tap water, and the nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin, rinsed, dehydrated, and coverslipped with Eukitt (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). For analysis, two or three random fields/slide were taken from three liver samples from each group at magnification of 40× on a Zeiss Axioplan microscope equipped with an Axiocam 105 color camera and Zen 2 software.

Fasting Glucose and Insulin

Following an overnight fast, a blood sample was obtained via orbital sinus under isoflurane anesthesia. Blood glucose was measured using an Accu-Chek Advantage glucometer (Roche Applied Science). Fasting plasma insulin concentrations were determined by ELISA (Linco Insulin ELISA kit) as previously described (48).

Biliverdin Reductase Assay

Biliverdin reductase activity was measured using a modified assay (49). Samples were homogenized in a potassium phosphate buffer (10 mm potassium phosphate, 25 mm sucrose, 1 mm EDTA, and 0.1 mm PMSF). Biliverdin reductase activity was then measured in 0.5 mg of protein homogenate in an assay buffer (50 mm Tris-base, 1 mm EDTA, pH 8.7, 1.2 mm NADPH, and 0.03 mm biliverdin). The activity assay was done in a final volume of 1 ml. The reactions were incubated in the dark for 15 min at 37 °C following by a 5-min incubation in the dark at 95 °C. Bilirubin levels in the assay samples were determined by spectroscopy at 468 nm using a standard curve of bilirubin IXα (50–300 μm). BVR activity was expressed as μmol of bilirubin/min/mg of protein.

Promoter Reporter Assays and PPARα Mutants Construct Generation

The Cos7 green kidney monkey cells used for the promoter assays were routinely cultured and maintained in DMEM containing 10% bovine calf serum or FBS with 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Expression vector for PPARα-3X-FLAG CMV was constructed as previously described1 (13). The S73A and S73D PPARα mutants were generated using QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit with the PPARα-3X-FLAG CMV plasmid according to the manufacturer's protocol (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The HA-tagged GSK3β WT and K85A pcDNA3 was a gift from Jim Woodgett (Addgene plasmids 14753 and 14755, respectively) (12). PPARα minimal promoter PPRE-3tk-luciferase activity was measured by luciferase in the previous of PPARα and/or GSK3β, and pRL-CMV Renilla reporter for normalization to transfection efficiency. Transient transfection was achieved using GeneFect (Alkali Scientific, Inc.). 24-h post-transfected cells were treated for 24 h in dialyzed fatty acid free FBS and then lysed. The luciferase assay was performed using the Promega dual luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, WI).

Quantitative Real Time PCR Analysis

Total RNA was harvested from WT and BVRA knock-out mice by lysing livers using a Qiagen Tissue Lyser LT (Qiagen) and then extraction by 5-Prime PerfectPure RNA tissue kit (Fisher Scientific). Total RNA was read on a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and cDNA was synthesized using a high capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). PCR amplification of the cDNA was performed by quantitative real time PCR using TrueAmp SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix (Alkali Scientific). The thermocycling protocol consisted of 5 min at 95 °C, 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, and 30 s at 60 °C and finished with a melting curve ranging from 60 to 95 °C to allow distinction of specific products. Normalization was performed in separate reactions with primers to GAPDH mRNA.

Gel Electrophoresis and Western Blotting

Mouse tissues were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen during harvesting and stored at −80 °C. For gel electrophoresis, 50–100 mg of cut tissue was then resuspended in 3 volumes of CelLytic Buffer (Sigma C3228) plus 10% protease inhibitor mixture (P2714-1BTL; Sigma) and Halt phosphatase inhibitor mixture (PI78420; Fisher), then incubated on ice for 30 min followed by lysing the livers using a Qiagen Tissue Lyser LT (Qiagen), and then centrifuged at 100,000 × g at 4 °C. Protein samples were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electrophoretically transferred to Immobilon-FL membranes. The membranes were blocked at room temperature for 2 h in TBS (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and 150 mm NaCl) containing 3% BSA. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following antibodies: PPARα (sc-9000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) (13119; Santa Cruz), serine 73 phospho-PPARα (described below), insulin receptor β (sc-711; Santa Cruz), GYS2 (sc-47109; Santa Cruz), GYS phosphoserine 641 (3891; Cell Signaling), AKT (9272S; Cell Signaling), phospho-AKT (4060S; Cell Signaling), AMPK (2532S; Cell Signaling), phospho-AMPK (2535S; Cell Signaling), FAS (3180S; Cell Signaling), phospho-ACC (3661S; Cell Signaling), GSK3β (9832S; Cell Signaling), phospho-GSK3β (9336S; Cell Signaling), and CPT1A (ab128568; Abcam). After three washes in TBS + 0.1% Tween 20, the membrane was incubated with an infrared anti-rabbit (IRDye 800, green) or anti-mouse (IRDye 680, red) secondary antibody labeled with IRDye infrared dye (LI-COR Biosciences) (1:10,000 dilution in TBS) for 2 h at 4 °C. Immunoreactivity was visualized and quantified by infrared scanning in the Odyssey system (LI-COR Biosciences).

Generation of Serine 73 Phospho-PPARα Antibody

To generate a phosphospecific antibody to a peptide corresponding to serine 73 at the N terminus of PPARα, 15 amino acids with phosphorylated serine 73 (VITDTLpSPASSPSS-Cys) was synthesized and purified by Pacific Immunology (Ramona, CA). The Ser(P)73-PPARα antibody was made as previously described in Ref. 13. In brief, an N-terminal cysteine was added to the peptide as a linker, followed by conjugation to a peptide carrier protein keyhole limpet hemocyanin and adjuvant-based immunization in a female New Zealand White rabbit. Preimmune serum was collected before injecting the rabbits with Ser(P)73-PPARα peptide conjugate. The rabbits were boosted 2 weeks after injection with the Ser(P)73-PPARα peptide with complete Freund's adjuvant and subsequently boosted two more times with incomplete Freund's adjuvant every 2 weeks. Serum was collected at 2 months and analyzed via ELISA for Ser(P)73-PPARα specific antibodies. Serum of high titer was obtained and subjected to one round of affinity purification using the Ser(P)73-PPARα peptide.

In Vitro Kinase Assay

PPARα, PPARα mutants, and PPARα domains were expressed as maltose-binding protein (MBP) fusion protein in DH5α bacteria and purified using amylose resin (New England Biolabs) as described previously (16). pMAL rPPARα mutants were generated using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Stratagene). Phosphorylation of MPB-PPARα, MBP-PPARα domains, and MPB-PPARα mutants was performed by incubating 2 μg of MBP-PPARα, 5 or 25 ng of active GSK3β (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), and 1 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) in kinase reaction buffer (40 mm MOPS, pH 7.0, 1 mm EDTA) according to the manufacturer's protocol for 90 min at 30 °C. The proteins were heated to 95 °C for 3 min and were separated on an 8% Tris-glycine gel, dried, and visualized by autoradiography (n = 3 separate experiments).

Ubiquitination of PPARα

After transfection (V5-rPPARα, HA-ubiquitin, pcDNA3.1 GSK3β, V5-rPPARα S73A, or empty vector; plasmids are described below) recovery, Cos-1 cells were co-treated with 50 μm WY-14643 ([4-chloro-6-(2,3-zylindino)-2-pyrimidinylthio] acetic acid, CAS no. 50892-23-4; BIOMOL International, Plymouth Meeting, PA) or 0.1% DMSO in the presence of 5 μm MG132 (carbobenzoxy-l-leucyl-l-leucyl-l-leucinal Z-LLL-CHO; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) for 4 h. The cells were lysed in 1 ml of RIPA buffer supplemented with mammalian protease inhibitor mixture and 10 μg/ml α-iodoacetamide (Calbiochem) on ice for 20 min. Equal amounts of protein (1.5 mg) were precleared with 50 μl of protein G-Sepharose for 2 h before incubation with 75 μl of protein G-Sepharose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) plus 1 μl anti-V5 antibody (R960-25, 1:5000; Invitrogen) overnight at 4 °C with rocking. Immune complexes were washed four times with RIPA buffer plus 10 μg/ml α-iodoacetamide, and proteins were eluted from the resin with 2× Tricine sample buffer, heated at 80 °C for 5 min, and separated on an 8% Tricine gel. The proteins were transferred to Hybond-ECL nitrocellulose, and the membrane was boiled in water for 5 min, immediately put into 5% nonfat dry milk blocking buffer, and probed for ubiquitinated PPARα using V5-HRP antibody (R96125, 1:5000; Invitrogen) for detection of mono-ubiquination and HA-antibody (SC-7392, 1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for detection of polyubiquination via Western blotting with detection by the addition of [125I]streptavidin (1:10,000; GE Healthcare) with n = 3 separate experiments. Plasmids for PPARα ubiquitination analysis are as follows: pcDNA3.1/V5-His-rPPARα (V5-rPPARα) was described previously (16), V5-rPPARα S73A mutant was generated using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Stratagene), pcDNA3.1 GSK3β was from Curtis Omiecinski (Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA), and HA-ubiquitin was from Dirk Bohmann (University of Rochester, Rochester, NY).

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed with Prism 6 (GraphPad Software) using analysis of variance combined with Tukey's post-test to compare pairs of group means or unpaired t tests. The results are expressed as means ± S.E. Additionally, one-way analysis of variance with a least significant difference post hoc test was used to compare mean values between multiple groups, and a two-tailed, and a two-way analysis of variance was utilized in multiple comparisons, followed by the Bonferroni post hoc analysis to identify interactions. p values of 0.05 or smaller were considered statistically significant.

Author Contributions

T. D. H. and D. E. S. conceived and coordinated the study and wrote the paper. K. A. B. and J. P. V. H. designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments shown in Fig. 6 (A–D) and contributed to the preparation of the figures and manuscript. T. D. H., L. M., and A. N.-K. designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments shown in Figs. 2 (A and B), 3 (D–F), 4, 5 (A–C), 6 (E and F), and 7 and contributed to the preparation of the figures. T. D. H. had the Ser(P)73 PPARα-Ab generated and tested specificity. Additionally, A. N.-K. performed the imaging in Figs. 3B, 4B, and 7 (B and C). D. E. S. developed the liver-specific biliverdin reductase knock-out mice. D. E. S., H. A. D., A. A. A., and M. W. H. developed and analyzed the experiments shown in Figs. 1, 2 (C and D), 3 (A–C), 4A, and 5D and contributed to the preparation of the figures. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the University of Toledo deArce-Memorial Endowment Fund (T.D.H). Research reported in this publication was also supported, in whole or part, by the National Institutes of Health [L32MD009154] (T.D.H.), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute [K01HL-125445] (T.D.H.) and [PO1HL-051971], [HL088421] (D.E.S.), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences [P20GM-104357] (D.E.S.), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [ES07799] (J.P.V.H.), and graduate student fellowship from Bristol Myers Squibb (K.A.B.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- NAFLD

- non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- BVR

- biliverdin reductase

- GSK

- glycogen synthase kinase

- NASH

- non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- PPAR

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; liver-specific BVRA knock-out

- AMPK

- AMP-activated protein kinase

- FAS

- fatty acid synthase

- ACC

- acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- GYS

- glycogen synthase

- GTT

- glucose tolerance test

- ITT

- insulin tolerance test

- RIPA

- radioimmune precipitation assay

- MBP

- maltose-binding protein

- Tricine

- N-[2-hydroxy-1, 1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine.

References

- 1. John K., Marino J. S., Sanchez E. R., and Hinds T. D. Jr. (2016) The glucocorticoid receptor: cause or cure for obesity? Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 310, E249–E257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Day C. P., and James O. F. (1998) Steatohepatitis: a tale of two “hits”? Gastroenterology 114, 842–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tilg H., and Moschen A. R. (2010) Evolution of inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the multiple parallel hits hypothesis. Hepatology 52, 1836–1846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hinds T. D. Jr., Sodhi K., Meadows C., Fedorova L., Puri N., Kim D. H., Peterson S. J., Shapiro J., Abraham N. G., and Kappas A. (2013) Increased HO-1 levels ameliorate fatty liver development through a reduction of heme and recruitment of FGF21. Obesity (Silver Spring) 22, 705–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 5. O'Brien L., Hosick P. A., John K., Stec D. E., and Hinds T. D. Jr. (2015) Biliverdin reductase isozymes in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metabol. 26, 212–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pereira P. J., Macedo-Ribeiro S., Párraga A., Pérez-Luque R., Cunningham O., Darcy K., Mantle T. J., and Coll M. (2001) Structure of human biliverdin IXβ reductase, an early fetal bilirubin IXβ producing enzyme. Nat. Struct. Biol 8, 215–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lerner-Marmarosh N., Shen J., Torno M. D., Kravets A., Hu Z., and Maines M. D. (2005) Human biliverdin reductase: a member of the insulin receptor substrate family with serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 7109–7114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stec D. E., John K., Trabbic C. J., Luniwal A., Hankins M. W., Baum J., and Hinds T. D. (2016) Bilirubin binding to PPARα inhibits lipid accumulation. PLoS One 11, e0153427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lu K., Han M., Ting H. L., Liu Z., and Zhang D. (2013) Scutellarin from Scutellaria baicalensis suppresses adipogenesis by upregulating PPARα in 3T3-L1 cells. J. Nat. Prod. 76, 672–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goto T., Lee J. Y., Teraminami A., Kim Y. I., Hirai S., Uemura T., Inoue H., Takahashi N., and Kawada T. (2011) Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α stimulates both differentiation and fatty acid oxidation in adipocytes. J. Lipid Res. 52, 873–884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu J., Wang L., Tian X. Y., Liu L., Wong W. T., Zhang Y., Han Q. B., Ho H. M., Wang N., Wong S. L., Chen Z. Y., Yu J., Ng C. F., Yao X., and Huang Y. (2015) Unconjugated bilirubin mediates heme oxygenase-1-induced vascular benefits in diabetic mice. Diabetes 64, 1564–1575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stambolic V., and Woodgett J. R. (1994) Mitogen inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 β in intact cells via serine 9 phosphorylation. Biochem. J. 303, 701–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hinds T. D. Jr., Ramakrishnan S., Cash H. A., Stechschulte L. A., Heinrich G., Najjar S. M., and Sanchez E. R. (2010) Discovery of glucocorticoid receptor-β in mice with a role in metabolism. Mol. Endocrinol. 24, 1715–1727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stienstra R., Mandard S., Patsouris D., Maass C., Kersten S., and Müller M. (2007) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α protects against obesity-induced hepatic inflammation. Endocrinology 148, 2753–2763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lebrun V., Molendi-Coste O., Lanthier N., Sempoux C., Cani P. D., van Rooijen N., Stärkel P., Horsmans Y., and Leclercq I. A. (2013) Impact of PPAR-α induction on glucose homoeostasis in alcohol-fed mice. Clin. Sci. 125, 501–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harano Y., Yasui K., Toyama T., Nakajima T., Mitsuyoshi H., Mimani M., Hirasawa T., Itoh Y., and Okanoue T. (2006) Fenofibrate, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α agonist, reduces hepatic steatosis and lipid peroxidation in fatty liver Shionogi mice with hereditary fatty liver. Liver Int. 26, 613–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Burns K. A., and Vanden Heuvel J. P. (2007) Modulation of PPAR activity via phosphorylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1771, 952–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Adams M., Reginato M. J., Shao D., Lazar M. A., and Chatterjee V. K. (1997) Transcriptional activation by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ is inhibited by phosphorylation at a consensus mitogen-activated protein kinase site. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 5128–5132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hinds T. D. Jr., Stechschulte L. A., Cash H. A., Whisler D., Banerjee A., Yong W., Khuder S. S., Kaw M. K., Shou W., Najjar S. M., and Sanchez E. R. (2011) Protein phosphatase 5 mediates lipid metabolism through reciprocal control of glucocorticoid receptor and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ). J. Biol. Chem. 286, 42911–42922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schadinger S. E., Bucher N. L., Schreiber B. M., and Farmer S. R. (2005) PPARγ2 regulates lipogenesis and lipid accumulation in steatotic hepatocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 288, E1195–E1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Imazu M., Strickland W. G., Chrisman T. D., and Exton J. H. (1984) Phosphorylation and inactivation of liver glycogen synthase by liver protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 1813–1821 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Oreña S. J., Torchia A. J., and Garofalo R. S. (2000) Inhibition of glycogen-synthase kinase 3 stimulates glycogen synthase and glucose transport by distinct mechanisms in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 15765–15772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ibrahim S. H., Akazawa Y., Cazanave S. C., Bronk S. F., Elmi N. A., Werneburg N. W., Billadeau D. D., and Gores G. J. (2011) Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) inhibition attenuates hepatocyte lipoapoptosis. J. Hepatol. 54, 765–772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chang Y. S., Tsai C. T., Huangfu C. A., Huang W. Y., Lei H. Y., Lin C. F., Su I. J., Chang W. T., Wu P. H., Chen Y. T., Hung J. H., Young K. C., and Lai M. D. (2011) ACSL3 and GSK-3β are essential for lipid upregulation induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress in liver cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 112, 881–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gibbs P. E., Lerner-Marmarosh N., Poulin A., Farah E., and Maines M. D. (2014) Human biliverdin reductase-based peptides activate and inhibit glucose uptake through direct interaction with the kinase domain of insulin receptor. FASEB J. 28, 2478–2491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lerner-Marmarosh N., Miralem T., Gibbs P. E., and Maines M. D. (2008) Human biliverdin reductase is an ERK activator; hBVR is an ERK nuclear transporter and is required for MAPK signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 6870–6875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Murgia M., Jensen T. E., Cusinato M., Garcia M., Richter E. A., and Schiaffino S. (2009) Multiple signalling pathways redundantly control glucose transporter GLUT4 gene transcription in skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 587, 4319–4327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Habets D. D., Coumans W. A., El Hasnaoui M., Zarrinpashneh E., Bertrand L., Viollet B., Kiens B., Jensen T. E., Richter E. A., Bonen A., Glatz J. F., and Luiken J. J. (2009) Crucial role for LKB1 to AMPKα2 axis in the regulation of CD36-mediated long-chain fatty acid uptake into cardiomyocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1791, 212–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chavez J. A., Roach W. G., Keller S. R., Lane W. S., and Lienhard G. E. (2008) Inhibition of GLUT4 translocation by Tbc1d1, a Rab GTPase-activating protein abundant in skeletal muscle, is partially relieved by AMP-activated protein kinase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 9187–9195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mandard S., Stienstra R., Escher P., Tan N. S., Kim I., Gonzalez F. J., Wahli W., Desvergne B., Müller M., and Kersten S. (2007) Glycogen synthase 2 is a novel target gene of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 64, 1145–1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zeng R., Yao Y., Han M., Zhao X., Liu X. C., Wei J., Luo Y., Zhang J., Zhou J., Wang S., Ma D., and Xu G. (2008) Biliverdin reductase mediates hypoxia-induced EMT via PI3-kinase and Akt. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 19, 380–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pachori A. S., Smith A., McDonald P., Zhang L., Dzau V. J., and Melo L. G. (2007) Heme-oxygenase-1-induced protection against hypoxia/reoxygenation is dependent on biliverdin reductase and its interaction with PI3K/Akt pathway. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 43, 580–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Badman M. K., Pissios P., Kennedy A. R., Koukos G., Flier J. S., and Maratos-Flier E. (2007) Hepatic fibroblast growth factor 21 is regulated by PPARα and is a key mediator of hepatic lipid metabolism in ketotic states. Cell Metab. 5, 426–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Berglund E. D., Li C. Y., Bina H. A., Lynes S. E., Michael M. D., Shanafelt A. B., Kharitonenkov A., and Wasserman D. H. (2009) Fibroblast growth factor 21 controls glycemia via regulation of hepatic glucose flux and insulin sensitivity. Endocrinology 150, 4084–4093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chau M. D., Gao J., Yang Q., Wu Z., and Gromada J. (2010) Fibroblast growth factor 21 regulates energy metabolism by activating the AMPK-SIRT1-PGC-1α pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 12553–12558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lundåsen T., Hunt M. C., Nilsson L. M., Sanyal S., Angelin B., Alexson S. E., and Rudling M. (2007) PPARα is a key regulator of hepatic FGF21. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 360, 437–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miralem T., Lerner-Marmarosh N., Gibbs P. E., Jenkins J. L., Heimiller C., and Maines M. D. (2016) Interaction of human biliverdin reductase with Akt/protein kinase B and phosphatidylinositol-dependent kinase 1 regulates glycogen synthase kinase 3 activity: a novel mechanism of Akt activation. FASEB J. 30, 2926–2944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Banko N. S., McAlpine C. S., Venegas-Pino D. E., Raja P., Shi Y., Khan M. I., and Werstuck G. H. (2014) Glycogen synthase kinase 3α deficiency attenuates atherosclerosis and hepatic steatosis in high fat diet-fed low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Am. J. Pathol. 184, 3394–3404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bowes A. J., Khan M. I., Shi Y., Robertson L., and Werstuck G. H. (2009) Valproate attenuates accelerated atherosclerosis in hyperglycemic apoE-deficient mice: evidence in support of a role for endoplasmic reticulum stress and glycogen synthase kinase-3 in lesion development and hepatic steatosis. Am. J. Pathol. 174, 330–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lee S., Yang W. K., Song J. H., Ra Y. M., Jeong J. H., Choe W., Kang I., Kim S. S., and Ha J. (2013) Anti-obesity effects of 3-hydroxychromone derivative, a novel small-molecule inhibitor of glycogen synthase kinase-3. Biochem. Pharmacol 85, 965–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yang Y., Li W., Liu Y., Li Y., Gao L., and Zhao J. J. (2014) α-lipoic acid attenuates insulin resistance and improves glucose metabolism in high fat diet-fed mice. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 35, 1285–1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fang X., Yu S. X., Lu Y., Bast R. C. Jr., Woodgett J. R., and Mills G. B. (2000) Phosphorylation and inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 by protein kinase A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 11960–11965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stocker R., Yamamoto Y., McDonagh A. F., Glazer A. N., and Ames B. N. (1987) Bilirubin is an antioxidant of possible physiological importance. Science 235, 1043–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stocker R. (2004) Antioxidant activities of bile pigments. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 6, 841–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jang B. K. (2012) Elevated serum bilirubin levels are inversely associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 18, 357–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kwak M. S., Kim D., Chung G. E., Kang S. J., Park M. J., Kim Y. J., Yoon J. H., and Lee H. S. (2012) Serum bilirubin levels are inversely associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 18, 383–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Puri K., Nobili V., Melville K., Corte C. D., Sartorelli M. R., Lopez R., Feldstein A. E., and Alkhouri N. (2013) Serum bilirubin level is inversely associated with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in children. J Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 57, 114–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Csongradi E., Docarmo J. M., Dubinion J. H., Vera T., and Stec D. E. (2012) Chronic HO-1 induction with cobalt protoporphyrin (CoPP) treatment increases oxygen consumption, activity, heat production and lowers body weight in obese melanocortin-4 receptor-deficient mice. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 36, 244–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Huang T. J. (2002) Detection of biliverdin reductase activity. Curr. Protoc. Toxicol 9, 4.1–4.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]