Abstract

Alcoholic liver disease is a pathological condition caused by overconsumption of alcohol. Because of the high morbidity and mortality associated with this disease, there remains a need to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying its etiology and to develop new treatments. Because peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) modulates ethanol-induced hepatic effects, the present study examined alterations in gene expression that may contribute to this disease. Chronic ethanol treatment causes increased hepatic CYP2B10 expression inPparβ/δ+/+ mice but not in Pparβ/δ−/− mice. Nuclear and cytosolic localization of the constitutive androstane receptor (CAR), a transcription factor known to regulate Cyp2b10 expression, was not different between genotypes. PPARγ co-activator 1α, a co-activator of both CAR and PPARβ/δ, was up-regulated in Pparβ/δ+/+ liver following ethanol exposure, but not in Pparβ/δ−/− liver. Functional mapping of the Cyp2b10 promoter and ChIP assays revealed that PPARβ/δ-dependent modulation of SP1 promoter occupancy up-regulated Cyp2b10 expression in response to ethanol. These results suggest that PPARβ/δ regulates Cyp2b10 expression indirectly by modulating SP1 and PPARγ co-activator 1α expression and/or activity independent of CAR activity. Ligand activation of PPARβ/δ attenuates ethanol-induced Cyp2b10 expression in Pparβ/δ+/+ liver but not in Pparβ/δ−/− liver. Strikingly, Cyp2b10 suppression by ligand activation of PPARβ/δ following ethanol treatment occurred in hepatocytes and was mediated by paracrine signaling from Kupffer cells. Combined, results from the present study demonstrate a novel regulatory role of PPARβ/δ in modulating CYP2B10 that may contribute to the etiology of alcoholic liver disease.

Keywords: cytochrome P450, gene regulation, liver, liver injury, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR), alcoholic liver disease, Kupffer cells, cytochrome P450 2B10, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ

Introduction

Chronic consumption of ethanol causes steatosis, hepatomegaly, hepatitis, fibrosis, and cirrhosis collectively referred to as alcoholic liver disease and has become a major health issue because of high morbidity and mortality (1, 2). Nutrient deficiencies, impaired fatty acid metabolism, induction of xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes, and increased oxidative stress are all associated with liver toxicity induced by ethanol (3). However, the precise molecular mechanisms underlying the cause of alcoholic liver disease are not well understood.

Nuclear receptors have key roles in regulating lipid homeostasis and inflammation during the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease (4, 5). For example, activation of constitutive androstane receptor (CAR)3 facilitates ethanol metabolism, resulting in enhanced liver damage by increasing oxidative stress, apoptosis, and accumulation of lipids in hepatocytes (6). By contrast, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPARα) shows a protective role in alcoholic liver disease because ethanol-treated Pparα−/− mice exhibit marked liver damage including hepatomegaly, hepatic inflammation, fibrosis, and apoptosis as compared with ethanol-treated Pparα+/+ mice (7). A recent study showed that PPARβ/δ, another PPAR subtype, prevents ethanol-induced hepatic effects by suppressing lipogenesis, modulating amino acid metabolism, and altering pyridoxal kinase activity (8). This is consistent with previous studies showing that PPARβ/δ protects against liver damage induced by various hepatotoxicants (9–11). Although the protective role of PPARβ/δ in chemically induced liver toxicity was demonstrated in several models, the detailed molecular mechanism(s) that mediate protection against alcoholic liver disease are not well understood. Thus, the present study focused on identifying and characterizing genes regulated by PPARβ/δ and their roles in alcoholic liver disease.

Results

PPARβ/δ Modulates Ethanol-induced Hepatic Cyp2b10 Expression

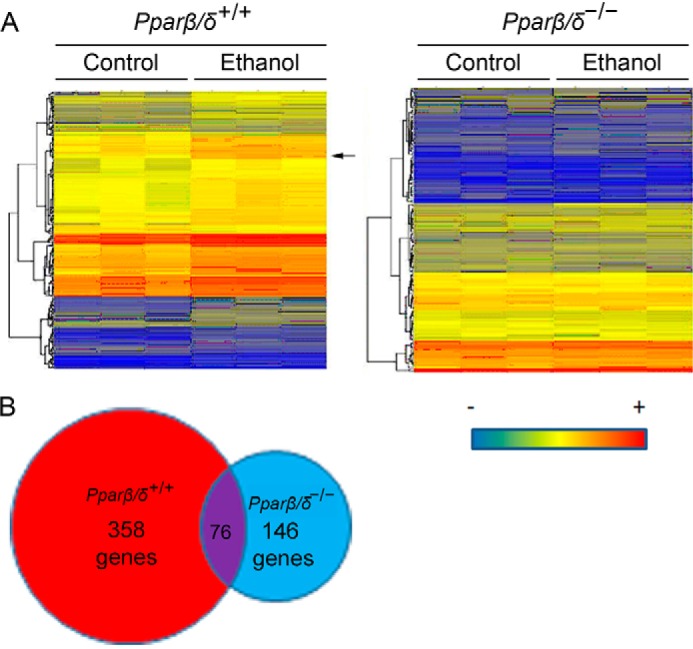

Microarray analysis was performed using liver RNA from Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mice to identify genes that were differentially regulated by ethanol (see NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus database accession number GSE86002). The gene expression profile was markedly different between genotype with distinct changes in gene expression noted in both Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mice (Fig. 1A). Of particular note was the PPARβ/δ-dependent increase in hepatic Cyp2b10 expression in Pparβ/δ+/+ but not Pparβ/δ−/− mice (Fig. 1A). This was of interest because previous studies demonstrated a similar PPARβ/δ-dependent effect on the hepatic expression of CYP2B10 in mice exposed to carbon tetrachloride (10). Overall, ethanol exposure significantly altered expression of 358 genes or 146 genes, in livers of Pparβ/δ+/+ or Pparβ/δ−/− mice, respectively (Fig. 1B), with very little overlap between genotypes (76 gene products).

FIGURE 1.

PPARβ/δ-dependent hepatic gene expression in response to ethanol exposure. A, heat map of hepatic gene expression from control and ethanol-treated Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mice as assessed by microarray analysis. The arrow in the left panel indicates that Cyp2b10 mRNA that was induced by ethanol in Pparβ/δ+/+ mice, but the induction was not observed in Pparβ/δ−/− mice. B, ethanol exposure altered expression of 358 genes and 146 genes, in Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mice, respectively. 76 genes overlapped.

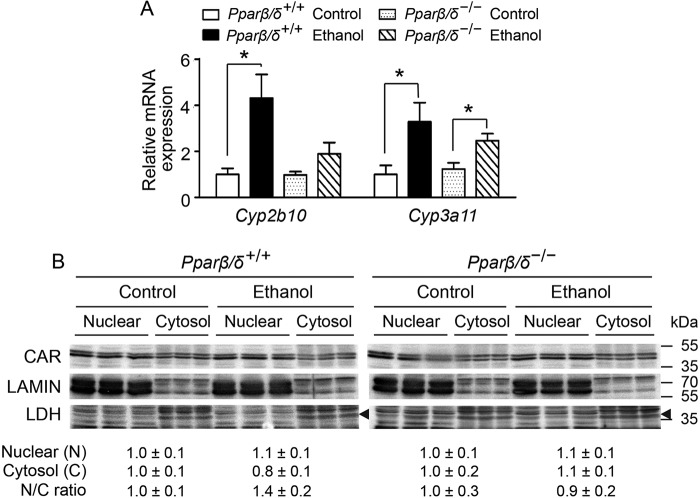

Ethanol-induced Cyp2b10 Expression Is Independent of CAR Signaling

Previous work revealed that ligand activation of CAR caused up-regulation of CYP2B10 in both Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mice (10). This suggested that CAR activity was not influenced by PPARβ/δ. However, whether PPARβ/δ modulated the ability of CAR to translocate and activate transcription of Cyp2b10 was not examined in the former study. Although expression of Cyp3a11 mRNA in the liver of Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mice fed ethanol was increased compared with controls, the expression of Cyp2b10 mRNA was increased in the liver of Pparβ/δ+/+ mice but not in Pparβ/δ−/− mice fed ethanol compared with controls (Fig. 2A). Because Cyp2b10 and Cyp3a11 are known target genes of CAR (12), but activating CAR with a ligand is not influenced by PPARβ/δ (10), the translocation of CAR was determined by quantitative Western blotting analysis. Interestingly, ethanol treatment did not influence the relative nuclear to cytosolic ratio of CAR expression compared with controls in either genotype (Fig. 2B). LAMIN and LDH were used as positive controls for nuclear and cytosolic enrichment.

FIGURE 2.

PPARβ/δ-dependent ethanol-induced Cyp2b10 expression is independent of CAR translocation. A, relative expression of hepatic Cyp2b10 and Cyp3a11 mRNA in control and ethanol-treated Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mice. B, quantitative Western blotting analysis of hepatic CAR expression in nuclear and cytosolic fractions of Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mice treated with or without ethanol. Arrowheads mark LDH. Relative expression level of nuclear CAR was normalized to that of LAMIN, and the relative expression level of cytosolic CAR was normalized to that of LDH. The values represent the means ± S.E. *, significantly different between groups (p ≤ 0.05).

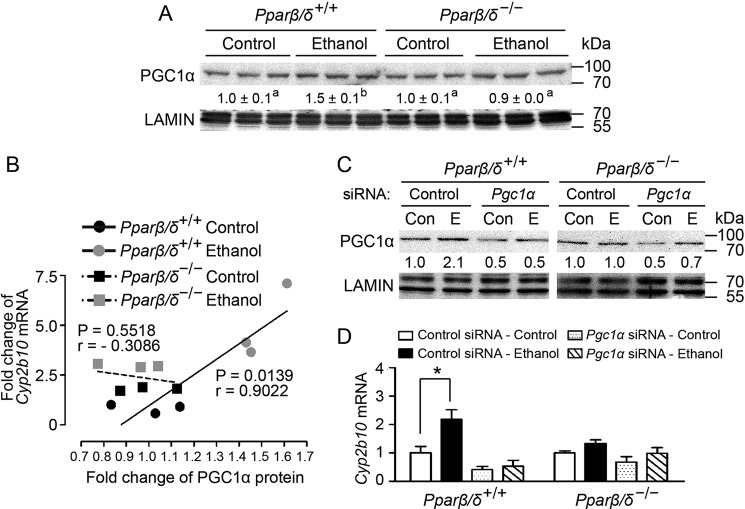

Ethanol-induced Hepatic Cyp2b10 Expression Is Associated with PPARβ/δ-dependent Expression of Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor γ Co-activator 1α (PGC1α)

Ethanol treatment caused increased nuclear PGC1α expression in Pparβ/δ+/+ mouse liver but not in Pparβ/δ−/− mouse liver compared with controls (Fig. 3A). Regression analysis revealed that ethanol-induced Cyp2b10 mRNA was positively correlated with higher nuclear PGC1α expression in Pparβ/δ+/+ mouse liver following ethanol treatment (Fig. 3B). However, this correlation was not found in Pparβ/δ−/− mouse liver compared with controls (Fig. 3B). To determine whether PPARβ/δ-dependent PGC1α expression is required for ethanol-induced Cyp2b10 expression, PGC1α was knocked down in primary hepatocytes from Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mice using siRNA. Quantitative Western blotting analysis confirmed the knockdown of PGC1α expression in hepatocytes from both genotypes and that ethanol increased nuclear PGC1α in Pparβ/δ+/+ mouse hepatocytes but not in Pparβ/δ−/− mouse hepatocytes compared with controls (Fig. 3C). Further, Cyp2b10 mRNA expression was increased in primary Pparβ/δ+/+ mouse hepatocytes by ethanol, but this effect was mitigated when PGC1α expression was knocked down (Fig. 3D). By contrast, ethanol had no effect on Cyp2b10 expression in Pparβ/δ−/− mouse hepatocytes compared with controls, and Cyp2b10 expression was also not influenced by knockdown of PGC1α; with or without ethanol (Fig. 3D). Because nuclear translocation of CAR is not influenced by PPARβ/δ expression, and previous studies demonstrated that ligand activation of CAR in mouse liver is unaffected by PPARβ/δ expression (10), these results suggest that the ethanol-induced expression of Cyp2b10 is dependent in part on PGC1α and PPARβ/δ.

FIGURE 3.

PGC1α is required for ethanol-induced Cyp2b10 expression in the liver. A, quantitative Western blotting analysis showing ethanol-induced nuclear PGC1α expression in the livers from Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mice. B, regression analysis of Cyp2b10 mRNA expression with nuclear PGC1α protein expression in the liver (n = 3 independent samples/group). C, quantitative Western blotting analysis of nuclear PGC1α expression. D, knocking down PGC1α attenuates ethanol-induced Cyp2b10 mRNA in primary hepatocytes from Pparβ/δ+/+ mice. The values represent the means ± S.E. *, significantly different between groups (p ≤ 0.05). The values with different letters are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

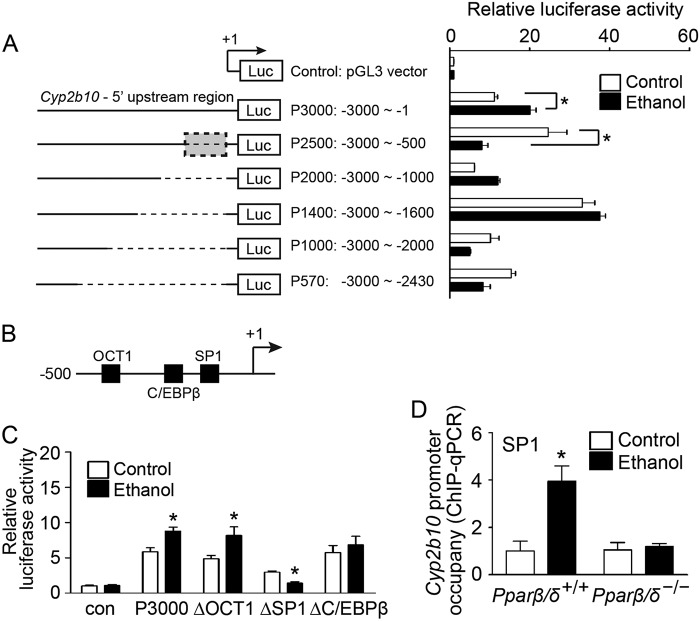

Ethanol-induced Hepatic Cyp2b10 Expression Is Regulated by PPARβ/δ-dependent Modulation of SP1 Activity

Because the previous results indicate that ethanol-induced Cyp2b10 expression was not mediated by CAR activation, functional mapping of the 5′ upstream region of the Cyp2b10 gene was performed to identify important regulators that may influence ethanol-induced Cyp2b10 expression. Reporter gene assays revealed that the −1 to −500 region of the Cyp2b10 promoter contained critical cis-regulatory elements that were responsive to ethanol exposure (Fig. 4A). The putative trans-acting factors in this region included the octamer-binding transcription factor 1 (OCT1), the CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β (C/EBPβ), and specificity protein 1 (SP1) (Fig. 4B). Mutation of the SP1-binding site in the Cyp2b10 promoter caused decreased luciferase activity following ethanol exposure compared with controls (Fig. 4C). However, this effect was not observed using either mutant OCT1 or mutant C/EBPβ constructs, indicating that these transcription factors are not required for ethanol-induced Cyp2b10 expression (Fig. 4C). A ChIP assay further confirmed that SP1 occupancy on the Cyp2b10 promoter was higher in ethanol-treated Pparβ/δ+/+ mouse hepatocytes compared with control (Fig. 4D). By contrast, SP1 occupancy of the Cyp2b10 promoter was not significantly different in Pparβ/δ−/− mouse hepatocytes treated with or without ethanol (Fig. 4D).

FIGURE 4.

PPARβ/δ regulates ethanol-induced Cyp2b10 expression by modulating SP1 activity. A, six luciferase reporter constructs (P3000, P2500, P2000, P1400, P1000, and P570) containing various fragments of 5′ upstream region of the mouse Cyp2b10 gene were generated (left panel). Primary hepatocytes were isolated from adult male Pparβ/δ+/+ mice. The cells were co-transfected with luciferase reporter constructs and pCMV-β-gal plasmid and treated with or without ethanol. Relative luciferase activity was determined and normalized to control group (right panel). B, putative cis-regulatory elements in the −1 to −500 bp of 5′upstream region of Cyp2b10 gene. C, site-directed mutagenesis was performed to generate luciferase reporter constructs carrying mutations in OCT1, SP1, or C/EBPβ binding sites of the Cyp2b10 5′upstream region. Primary hepatocytes were transfected with mutant luciferase reporter constructs and treated with or without ethanol. Relative luciferase activity was determined and normalized to control (Con). D, ChIP-qPCR showing PPARβ/δ-dependent increased SP1 occupancy on the Cyp2b10 promoter in response to ethanol exposure in primary hepatocytes. The values were corrected for background using rabbit IgG controls and represent the means ± S.E. *, significantly different from controls (p ≤ 0.05).

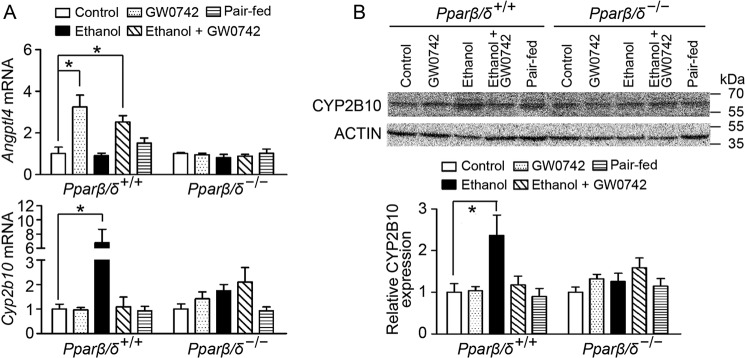

Ligand Activation of PPARβ/δ Attenuates Ethanol-induced Hepatic CYP2B10 Expression

To further address the critical role of PPARβ/δ in modulating alcohol-induced liver injury, Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mice were treated with the PPARβ/δ ligand GW0742 with or without ethanol exposure. Ligand activation of PPARβ/δ, with or without ethanol exposure increased expression of Angptl4 mRNA, a well known PPARβ/δ target gene in Pparβ/δ+/+ mouse liver but not in Pparβ/δ−/− mouse liver (Fig. 5A). Hepatic Cyp2b10 mRNA expression in Pparβ/δ+/+ mice fed the ethanol diet was higher than controls (Fig. 5A). Although ligand activation of PPARβ/δ with GW0742 did not influence the basal level of Cyp2b10 mRNA in Pparβ/δ+/+ liver, ethanol-induced Cyp2b10 mRNA expression was significantly suppressed by ligand activation of PPARβ/δ in Pparβ/δ+/+ mouse liver compared with controls (Fig. 5A). These observations were consistent with quantitative Western blotting analysis, showing that microsomal expression of hepatic CYP2B10 was induced by ethanol treatment in Pparβ/δ+/+ mice, and this induction was diminished by ligand activation of PPARβ/δ (Fig. 5B). No significant changes in hepatic CYP2B10 mRNA and protein expression were observed in any groups of Pparβ/δ−/− mice (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

Ligand activation of PPARβ/δ suppresses ethanol-induced hepatic CYP2B10 expression in vivo. A, expression of Angptl4 and Cyp2b10 mRNA in the liver from Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mice. B, quantitative Western blotting analysis of hepatic CYP2B10 expression following ligand activation of PPARβ/δ with GW0742. The values represent the means ± S.E. *, significantly different between groups (p ≤ 0.05).

Paracrine Signaling from Intact Kupffer Cells Is Required for PPARβ/δ-dependent Cyp2b10 Expression in Hepatocytes

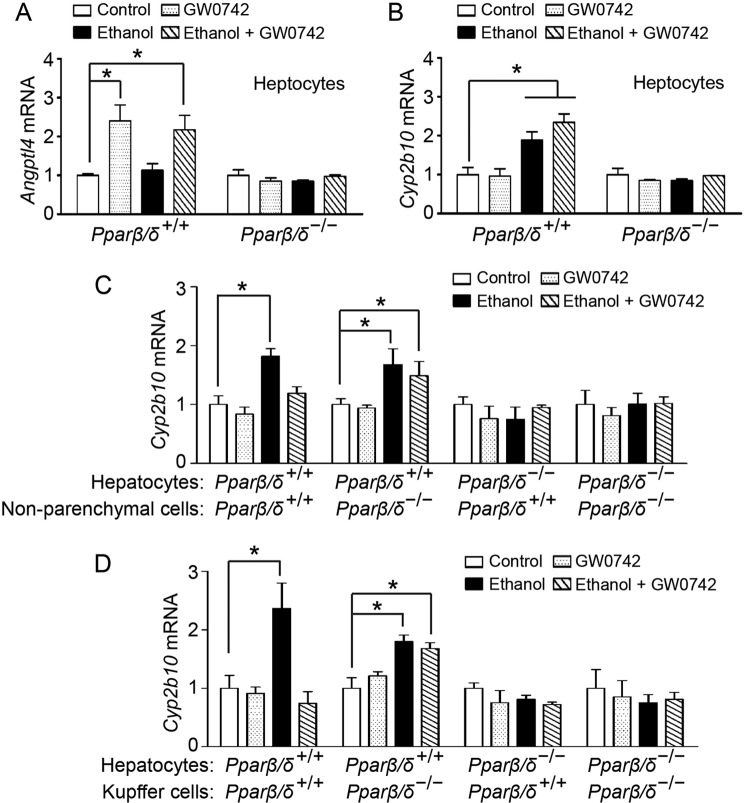

To determine the specific cell types that mediate attenuation of ethanol-induced Cyp2b10 expression in liver, co-cultures of primary hepatocytes, primary non-parenchymal cells or Kupffer cells alone isolated from Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mice were examined. In the presence or absence of ethanol treatment, ligand activation of PPARβ/δ increased Angptl4 mRNA expression in Pparβ/δ+/+ hepatocytes but not in Pparβ/δ−/− hepatocytes (Fig. 6A). Surprisingly, ligand activation of PPARβ/δ did not suppress ethanol-induced Cyp2b10 mRNA expression in Pparβ/δ+/+ hepatocytes (Fig. 6B), inconsistent with the results observed in vivo (Fig. 5A). Co-culturing primary hepatocytes with non-parenchymal cells revealed that the decrease in ethanol-induced Cyp2b10 mRNA expression following ligand activation of PPARβ/δ was restored and that this rescue was effective when hepatocytes were co-cultured solely with Kupffer cells (Fig. 6, C and D). These changes in Cyp2b10 mRNA expression were not observed in any groups of Pparβ/δ−/− co-cultures (Fig. 6, C and D).

FIGURE 6.

Paracrine signaling from Kupffer cells is required to modulate PPARβ/δ-dependent expression of Cyp2b10 in hepatocytes. A and B, expression of Angptl4 (A) and Cyp2b10 (B) mRNA in primary hepatocytes from Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mice. C and D, primary non-parenchymal cells (C) or primary Kupffer cells (D) from Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mice were co-cultured with primary hepatocytes in Transwell® culture plates. The values represent the means ± S.E. *, significantly different between groups (p ≤ 0.05).

Discussion

The metabolism of ethanol is mediated by enzymes including alcohol dehydrogenase and cytochrome P450s (CYP2E1 and CYP2B) (13). Oxidation of ethanol produces highly reactive oxygen species, which can cause liver damage (14, 15). Variation in the expression of these enzymes influences the sensitivity and the adaption to ethanol consumption (13). PPARβ/δ can protect against chemically induced liver injury through multiple mechanisms including inhibition of steatosis, inhibition of NF-kB-dependent signaling, and inhibition of inflammation (10, 11, 16, 17). A previous study revealed that exposure to carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) caused an increase in hepatic Cyp2b10 expression, and this induction was mediated by PPARβ/δ, which was not due to differences in the relative expression of CAR (10), similar to the results observed in the present study. The present study also showed that ethanol induced Cyp2b10 expression through a mechanism that required PPARβ/δ. Expression of Cyp2b10 is thought to be mediated by CAR activation (18). However, the present study clearly showed that ethanol treatment did not influence the relative expression of CAR as also observed in a previous study (10) or enhance the nuclear translocation of CAR following treatment with ethanol. Because the translocation of CAR to the nucleus is required to initiate target gene expression (19–21), this illustrates a unique finding from the present study because the results indicate that PPARβ/δ, rather than CAR, is required for up-regulation of Cyp2b10 in response to ethanol. This is similar to the PPARβ/δ-dependent up-regulation of hepatic Cyp2b10 observed following treatment with CCl4, and the fact that ligand activation of CAR caused up-regulation of Cyp2b10 in both Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mouse liver (10).

An alternative pathway that could be influenced by PPARβ/δ that impacts CAR activity is the relative expression of PGC1α. It is known that PPARβ/δ regulates PGC1α expression (22) and that CAR requires PGC1α as a co-activator to remodel chromatin of target genes (23). The present study demonstrated that nuclear PGC1α level was increased by ethanol treatment, and this increased expression of PGC1α requires PPARβ/δ. Indeed, PPARβ/δ-dependent expression of PGC1α is required for the increase in ethanol-induced Cyp2b10 expression because knocking down PGC1α prevented this effect in wild-type hepatocytes. This is the first study to demonstrate the essential role of PPARβ/δ-dependent expression of PGC1α in regulating Cyp2b10 expression in response to ethanol exposure. These findings suggest that one mechanism that may mediate the PPARβ/δ-dependent expression of Cyp2b10 is via modulation of PGC1α, which is required for CAR activation. The present studies strongly support this notion, but further work is needed to confirm this hypothesis. Interestingly, the basal level of Cyp2b10 mRNA expression was not altered by knocking down PGC1α compared with controls, suggesting that PGC1α is not critical for regulating constitutive Cyp2b10 expression.

In addition to CAR, the transcription factor SP1 also regulates Cyp2b1 expression in rat hepatocytes (24). The present study revealed that ethanol-induced increased promoter occupancy of SP1 on the Cyp2b10 gene, and this effect required the expression of PPARβ/δ. Examination of the microarray data did not indicate an increase in the expression of Sp1 mRNA. However, PGC1α can also increase SP1-mediated gene expression by either increasing SP1 expression or enhancing the recruitment of SP1 to the transcription complex (25, 26). Thus, it is possible that the PPARβ/δ-dependent expression of PGC1α induced by ethanol may also indirectly regulate Cyp2b10 expression by influencing the occupancy of SP1 on the Cyp2b10 promoter.

Because expression of CYPs is known to be involved in alcoholic liver disease in part because of the generation of metabolites such as reactive oxygen species, the finding that ligand activation of PPARβ/δ significantly suppressed ethanol-induced hepatic CYP2B10 expression suggests a protective role of PPARβ/δ in alcoholic liver disease. Indeed, recent studies have shown that PPARβ/δ protects against alcoholic liver disease by inhibiting steatosis, amino acid metabolism, and pyridoxal phosphate activity (8). Similarly, ligand activation of PPARβ/δ restores insulin sensitivity and also protects against ethanol-induced liver injury (17). However, ligand activation of PPARβ/δ did not prevent ethanol-induced Cyp2b10 mRNA expression in primary hepatocytes alone. By contrast, ligand activation of PPARβ/δ repression of Cyp2b10 expression induced by ethanol is restored when primary hepatocytes are co-cultured with Kupffer cells. This suggests that PPARβ/δ in the Kupffer cell may function differently than in the hepatocyte. For example, PPARβ/δ can modulate gene expression by interacting with other transcription factors and/or by directly regulating target gene expression (reviewed in Ref. 27). Indeed, PPARβ/δ expression in Kupffer cells can modulate effects observed during inflammatory insults in the liver that impact the hepatocyte (28). Further studies are needed to delineate the specific activities of PPARβ/δ in Kupffer cells and hepatocytes that underlie these differences. To date, this is the first demonstration that Kupffer cell activity is required for a protective effect in hepatocytes by facilitating repression of CYP2B10, whose expression is dependent on PPARβ/δ. This suggests that paracrine signaling between the Kupffer cell and hepatocyte may be important for preventing alcoholic liver disease through a PPARβ/δ-dependent mechanism.

It should be noted that there are advantages and disadvantages of using primary cells or co-cultures to study cell-cell interactions (29–31). For example, global transcriptional regulation is not always consistent in human primary hepatocyte cultures from different individuals (32). This suggests that there can be interindividual variability in response to chemical exposures and illustrates the need to define consistent culture condition when using primary cell cultures. The co-culture of hepatocytes with non-parenchymal cells has been shown to respond differently to chemical exposures, such as exhibiting greater drug metabolism capabilities and drug-induced inflammatory responses, compared with hepatocyte culture alone (33). Although this type of co-culture is designed to model the environmental condition in vivo, challenges remain required to enhance the in vivo-like characteristics of in vitro culture systems. A recent study revealed a unique and stable model because multicell cultures of parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells retain the functional ability of liver cells in response to chemical exposures (34) and may be suitable for studies similar to those performed in the present experiments.

The facts that PPARβ/δ protects against alcoholic liver disease (8, 17) and that this protection could be related to the repression of Cyp2b10 following exposure to ethanol are of interest. Therefore, further studies are needed to determine whether this PPARβ/δ-dependent regulation of Cyp2b10 can be used to identify novel markers of alcoholic liver progression and possibly be suitable for targeting for the prevention and/or treatment of this disease.

Experimental Procedures

Animals and Experimental Protocols

Animal usage was approved by the Pennsylvania State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Wild-type (Pparβ/δ+/+) and Pparβ/δ-null (Pparβ/δ−/−) mice (35) on a C57BL/6 genetic background were housed in a vivarium as previously described (36). Two cohorts of mice were used for the study. For the first cohort, age-matched (8–10 weeks) male Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mice were fed ad libitum daily with either liquid control or ethanol diets (Dyets Inc., Bethlehem, PA) for 16 weeks (n = 10 per group). The ethanol diet contained 4% (v/v) ethanol and was prepared as previously described (8). Samples from the first cohort of experimental mice were used for microarray analyses and hepatic gene/protein expression in response to ethanol treatment.

For the second cohort of mice, age-matched (10–12 weeks) male Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mice were fed ad libitum with liquid control or ethanol diet for 16 weeks (n = 10/group). Mice fed with control or ethanol diet were also given a pellet made with bacon-flavored Transgenic Dough Diet (Bioserv, Inc., Prospect, CT) mixed with vehicle control (0.02% dimethyl sulfoxide) or GW0742 (5 mg/kg/day) (n = 5/group). Pair-fed mice (n = 5/genotype) were included to control for potential difference in average food intake between control and ethanol diet. However, no differences in food intake were noted, so this group was not used for all analyses. Samples from the second cohort of mice were used for analysis of CYP2B10 expression in livers.

Microarray Analysis

Total RNA was isolated as previously described (37). Purified RNA was assessed by GeneChip Mouse Gene 2.0 ST array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) following the manufacturer's recommended procedures. The robust multichip average approach was applied to normalize microarray data as previously described (37). The p value < 0.05 and a fold change of 1.5 in the intensity of signals were used to identify genes that were significantly regulated by ethanol treatment. The data were uploaded to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus database with the accession number GSE86002.

Quantitative Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR)

Expression of mouse Cyp2b10, Cyp3a11, and Angptl4 in response to ethanol treatment was determined by qPCR analysis as previously described (38). Briefly, total RNA was isolated using RiboZol RNA extraction reagent (AMRESCO, Solon, OH) following the manufacturer's recommended procedures. cDNA was synthesized using 1.25 μg of total RNA as template mixed with Moloney MLV reverse transcriptase and random primers (Promega, Madison, WI). DNA amplification was carried out in 25-μl volumes containing SYBR Green PCR Supermix (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD) using the iCycler iQ5 PCR thermal cycler (Bio-Rad) with 45–55 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. The sequences of primers used to detect mRNA were Cyp2b10 (NM_009999.4): forward, 5′-TTCTGCGCATGGAGAAGGAGAAGT-3′ and reverse, 5′-TGAGCATGAGCAGGAAGCCATAGT-3′; Cyp3a11(NM_007818.3): forward, 5′-GACAAACAAGCAGGGATGGAC-3′ and reverse, 5′-CCAAGCTGATTGCTAGGAGCA-3′; and Angptl4 (NM_020581.2): forward, 5′-TTCTCGCCTACCAGAGAAGTTGGG-3′ and reverse, 5′-CATCCACAGCACCTACAACAGCAC-3′. The expression of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh; BC083149) was quantified as an internal control using the forward and reverse primers: 5′-GGTGGAGCCAAAAGGGTCAT-3′ and 5′-GGTTCACACCCATCACAAACAT-3′. The primers were designed that spanned exon-exon junctions, which prevents genomic DNA amplification. Each assay included a standard curve and a non-template control that were performed in triplicate. Four to six representative tissue samples/treatment group were randomly chosen for each analysis. Relative mRNA levels were normalized to Gapdh because there was no difference in expression between groups as determined by ANOVA and post hoc testing (p ≥ 0.05).

Western Blotting Analysis

Hepatic microsomal protein was extracted from Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mouse livers as previously described (39). Nuclear and cytosolic fractions were isolated from Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mouse livers using NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents (Pierce) following the manufacturer's recommended procedures. Quantitative Western blotting analysis using radioactive detection techniques, the gold standard for quantifying protein expression, was performed as previously described (40). The following primary antibodies were used: anti-LAMIN A/C (sc7293, lot no. L0909, mouse monoclonal; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA); anti-ACTIN (sc47778, lot no. K1414, mouse monoclonal, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies); anti-LDH (200-1173, lot no. 11538, goat polyclonal; Rockland Immunochemicals, Inc., Limerick, PA); anti-CYP2B1 (clone 2-66-3 (41), mouse monoclonal, produced at the National Cancer Institute as previously described (41, 42)); anti-PGC1α (ab51365, clone PPARAH6, mouse monoclonal; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and anti-CAR (PP-N4111-00, lot no. A-1, mouse monoclonal; R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Specificity of the antibodies was confirmed through different methods including: 1) confirming relative mobility for each protein (69/62 kDa for LAMIN A/C, respectively; 43 kDa for ACTIN; 36 kDa for LDH; 57 kDa for CYP2B10; 89 kDa for PGC1α; or 40 kDa for CAR); 2) confirming relative mobility and subcellular localization in the nucleus versus cytosol (CAR, LDH, or LAMIN A/C); 3) confirming relative mobility and knockdown of protein expression (PGC1α); or 4) confirming relative mobility and lack of inducibility in knock-out mice (CYP2B10). The relative expression level of each microsomal or cytosolic protein was normalized to the value of LDH or ACTIN. The relative expression level of each nuclear protein was normalized to the value of LAMIN. Statistical analyses of hybridization signals for LDH, ACTIN, and LAMIN revealed no significant differences between treatment groups as assessed by ANOVA and post hoc testing (p ≥ 0.05). A minimum of three mice per group was analyzed.

Primary Hepatic Cell Isolation

Primary hepatocytes, Kupffer cells and non-parenchymal cells were isolated from adult male Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mice as previously described (43). Primary hepatocytes (2 × 105) were seeded in 12-well collagen-coated culture plates (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and cultured in HepatoZYME medium (Gibco) at 37 °C with 5% carbon dioxide. Primary Kupffer cells or non-parenchymal cells were seeded in normal 12-well culture plates and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen).

siRNA Knockdown of Mouse PGC1α in Primary Hepatocytes

Primary hepatocytes (2 × 105) were seeded in 12-well collagen-coated culture plates and transiently transfected with 10 μm non-targeting scrambled siRNA or mouse Pgc1α siRNA (Invitrogen) using LipofectamineTM 2000 following the manufacturer's recommended procedures. The cells were treated with or without ethanol (≤100 mm) for 12 h. Quantitative Western blotting analysis was performed as described above to confirm nuclear PGC1α expression.

Luciferase Assay

To identify the cis-regulatory element responsible for ethanol-induced Cyp2b10 expression in hepatocytes, six reporter gene constructs driven by 5′ upstream region of Cyp2b10 gene with serial deletion were generated by PCR. Primers were designed to contain overhanging sites for restriction enzymes, which allowed for directional cloning into the multiple cloning site of pGL3-basic luciferase reporter vector (Promega). The composition of each construct was confirmed by restriction endonuclease digestion and DNA sequencing.

Primary hepatocytes were transiently co-transfected with 0.5 μg of pCMV-β-galactosidase plasmid (Promega) and 3.5 μg of either Cyp2b10 promoter-luciferase reporter constructs or the control plasmid (pGL3-basic vector) using Lipofectamine LTX reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's recommended procedures. The cells were treated with or without ethanol (≤100 mm) for 12 h, and cell lysates were prepared in passive lysis buffer (Promega). Luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured using Luciferase and Beta-Glo assay systems, respectively, following the manufacturer's recommended procedures. Relative luciferase activity was normalized to β-galactosidase activity.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

DpnI-mediated site-directed mutagenesis was performed to generate mutation in Cyp2b10 promoter-luciferase reporter construct as previously described (44). The sequence-specific primers were overlapping with and flanking the transcription factor binding sites for identified trans-acting factors. The successful mutagenesis was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Primary hepatocytes were transiently transfected with mutant luciferase reporter constructs followed by ethanol treatment. Relative luciferase activity was determined as described above.

ChIP-qPCR

To confirm the occupancy of SP1 on the Cyp2b10 promoter, ChIP-qPCR was performed to quantify relative promoter occupancy following ethanol exposure in primary hepatocytes from Pparβ/δ+/+ and Pparβ/δ−/− mice as previously described (38). The following primary antibody was used: anti-SP1 (sc59, lot no. 0915, rabbit polyclonal; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies). Rabbit IgG was used a negative control.

Co-cultures of Primary Hepatocytes with Primary Kupffer Cells or Non-parenchymal Cells

Primary hepatocytes were seeded in 12-well collagen-coated culture plates. Primary Kupffer cells or non-parenchymal cells were seeded in Transwell® inserts (Corning Inc., Corning, NY). Primary hepatocyte-Kupffer cell co-cultures (5:1 ratio) or primary hepatocyte-non-parenchymal cell co-cultures (1:1 ratio) were pretreated with or without GW0742 (1 μm) for 6 h and then treated with or without ethanol (≤100 mm) for 12 h.

Statistical Analysis

The data were subjected to either Student's t test or a parametric one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey test for post hoc comparisons (Prism 5.0; GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). The correlation between fold changes of Cyp2b10 mRNA expression and nuclear PGC1α protein expression was determined by Pearson correlation method with a two-tailed p value (Prism 5.0).

Author Contributions

T. K., P.-L. Y., M. G., G. H. P., A. J. F., F. J. G., and J. M. P. conceived and coordinated the study and wrote the paper. T. K., G. B., P.-L. Y., and I. A. M. performed and analyzed experiments. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the Genomics Core Facility at the Huck Institutes of Life Sciences of the Pennsylvania State University for technical support with DNA sequencing and microarray data analysis. We also acknowledge Combiz Khozoie and Susan Mitchell for technical assistance with these studies.

This work was supported by National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants CA124533 and CA141029 (to J. M. P.) and AA018863 (to A. J. F. and J. M. P.) and National Institutes of Health NCI Intramural Research Program Grants ZIABC005561, ZIABC005562, and ZIABC005708 (to F. J. G.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- CAR

- constitutive androstane receptor

- PPAR

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- PGCα

- PPARγ co-activator α

- LDH

- lactate dehydrogenase

- qPCR

- quantitative real time PCR

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance.

References

- 1. Dunn W., and Shah V. H. (2016) Pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease. Clin. Liver Dis. 20, 445–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chacko K. R., and Reinus J. (2016) Spectrum of alcoholic liver disease. Clin. Liver Dis. 20, 419–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lieber C. S. (2003) Relationships between nutrition, alcohol use, and liver disease. Alcohol. Res. Health 27, 220–231 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gyamfi M. A., and Wan Y. J. (2010) Pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease: the role of nuclear receptors. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 235, 547–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moriya T., Naito H., Ito Y., and Nakajima T. (2009) “Hypothesis of seven balances”: molecular mechanisms behind alcoholic liver diseases and association with PPARα. J. Occup. Health 51, 391–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen X., Meng Z., Wang X., Zeng S., and Huang W. (2011) The nuclear receptor CAR modulates alcohol-induced liver injury. Lab. Invest. 91, 1136–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nakajima T., Kamijo Y., Tanaka N., Sugiyama E., Tanaka E., Kiyosawa K., Fukushima Y., Peters J. M., Gonzalez F. J., and Aoyama T. (2004) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α protects against alcohol-induced liver damage. Hepatology 40, 972–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goudarzi M., Koga T., Khozoie C., Mak T. D., Kang B. H., Fornace A. J. Jr., and Peters J. M. (2013) PPARβ/δ modulates ethanol-induced hepatic effects by decreasing pyridoxal kinase activity. Toxicology 311, 87–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nagasawa T., Inada Y., Nakano S., Tamura T., Takahashi T., Maruyama K., Yamazaki Y., Kuroda J., and Shibata N. (2006) Effects of bezafibrate, PPAR pan-agonist, and GW501516, PPARδ agonist, on development of steatohepatitis in mice fed a methionine- and choline-deficient diet. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 536, 182–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shan W., Nicol C. J., Ito S., Bility M. T., Kennett M. J., Ward J. M., Gonzalez F. J., and Peters J. M. (2008) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ protects against chemically induced liver toxicity in mice. Hepatology 47, 225–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shan W., Palkar P. S., Murray I. A., McDevitt E. I., Kennett M. J., Kang B. H., Isom H. C., Perdew G. H., Gonzalez F. J., and Peters J. M. (2008) Ligand activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ (PPARβ/δ) attenuates carbon tetrachloride hepatotoxicity by downregulating proinflammatory gene expression. Toxicol. Sci. 105, 418–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Qatanani M., and Moore D. D. (2005) CAR, the continuously advancing receptor, in drug metabolism and disease. Curr. Drug Metab. 6, 329–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cederbaum A. I. (2012) Alcohol metabolism. Clin. Liver Dis. 16, 667–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deng X. S., and Deitrich R. A. (2007) Ethanol metabolism and effects: nitric oxide and its interaction. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2, 145–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zakhari S. (2006) Overview: how is alcohol metabolized by the body? Alcohol. Res. Health 29, 245–254 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bojic L. A., Telford D. E., Fullerton M. D., Ford R. J., Sutherland B. G., Edwards J. Y., Sawyez C. G., Gros R., Kemp B. E., Steinberg G. R., and Huff M. W. (2014) PPARδ activation attenuates hepatic steatosis in Ldlr−/− mice by enhanced fat oxidation, reduced lipogenesis, and improved insulin sensitivity. J. Lipid Res. 55, 1254–1266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pang M., de la Monte S. M., Longato L., Tong M., He J., Chaudhry R., Duan K., Ouh J., and Wands J. R. (2009) PPARδ agonist attenuates alcohol-induced hepatic insulin resistance and improves liver injury and repair. J. Hepatol. 50, 1192–1201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ding X., Lichti K., Kim I., Gonzalez F. J., and Staudinger J. L. (2006) Regulation of constitutive androstane receptor and its target genes by fasting, cAMP, hepatocyte nuclear factor α, and the coactivator peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 26540–26551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kobayashi K., Sueyoshi T., Inoue K., Moore R., and Negishi M. (2003) Cytoplasmic accumulation of the nuclear receptor CAR by a tetratricopeptide repeat protein in HepG2 cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 64, 1069–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hosseinpour F., Moore R., Negishi M., and Sueyoshi T. (2006) Serine 202 regulates the nuclear translocation of constitutive active/androstane receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 69, 1095–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kawamoto T., Sueyoshi T., Zelko I., Moore R., Washburn K., and Negishi M. (1999) Phenobarbital-responsive nuclear translocation of the receptor CAR in induction of the CYP2B gene. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 6318–6322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hondares E., Pineda-Torra I., Iglesias R., Staels B., Villarroya F., and Giralt M. (2007) PPARδ, but not PPARα, activates PGC-1α gene transcription in muscle. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 354, 1021–1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Corton J. C., and Brown-Borg H. M. (2005) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1 in caloric restriction and other models of longevity. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 60, 1494–1509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Muangmoonchai R., Smirlis D., Wong S. C., Edwards M., Phillips I. R., and Shephard E. A. (2001) Xenobiotic induction of cytochrome P450 2B1 (CYP2B1) is mediated by the orphan nuclear receptor constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) and requires steroid co-activator 1 (SRC-1) and the transcription factor Sp1. Biochem. J. 355, 71–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shin S. W., Yun S. H., Park E. S., Jeong J. S., Kwak J. Y., and Park J. I. (2015) Overexpression of PGC1α enhances cell proliferation and tumorigenesis of HEK293 cells through the upregulation of Sp1 and Acyl-CoA binding protein. Int. J. Oncol. 46, 1328–1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Salatino S., Kupr B., Baresic M., van Nimwegen E., and Handschin C. (2016) The genomic context and corecruitment of SP1 affect ERRα coactivation by PGC-1α in muscle cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 30, 809–825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Peters J. M., Foreman J. E., and Gonzalez F. J. (2011) Dissecting the role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) in colon, breast and lung carcinogenesis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 30, 619–640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Balandaram G., Kramer L. R., Kang B. H., Murray I. A., Perdew G. H., Gonzalez F. J., and Peters J. M. (2016) Ligand activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ suppresses liver tumorigenesis in hepatitis B transgenic mice. Toxicology 363–364, 1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bogdanowicz D. R., and Lu H. H. (2013) Studying cell-cell communication in co-culture. Biotechnol. J. 8, 395–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goers L., Freemont P., and Polizzi K. M. (2014) Co-culture systems and technologies: taking synthetic biology to the next level. J. R. Soc. Interface 11, 20140065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hawksworth G. M. (1994) Advantages and disadvantages of using human cells for pharmacological and toxicological studies. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 13, 568–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Goyak K. M., Johnson M. C., Strom S. C., and Omiecinski C. J. (2008) Expression profiling of interindividual variability following xenobiotic exposures in primary human hepatocyte cultures. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 231, 216–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Soldatow V. Y., Lecluyse E. L., Griffith L. G., and Rusyn I. (2013) In vitro models for liver toxicity testing. Toxicol. Res. (Camb.) 2, 23–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bale S. S., Geerts S., Jindal R., and Yarmush M. L. (2016) Isolation and co-culture of rat parenchymal and non-parenchymal liver cells to evaluate cellular interactions and response. Sci. Rep. 6, 25329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Peters J. M., Lee S. S., Li W., Ward J. M., Gavrilova O., Everett C., Reitman M. L., Hudson L. D., and Gonzalez F. J. (2000) Growth, adipose, brain, and skin alterations resulting from targeted disruption of the mouse peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β(δ). Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 5119–5128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yao P. L., Chen L., Hess R. A., Müller R., Gonzalez F. J., and Peters J. M. (2015) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-D (PPARD) coordinates mouse spermatogenesis by modulating extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-dependent signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 23416–23431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Khozoie C., Borland M. G., Zhu B., Baek S., John S., Hager G. L., Shah Y. M., Gonzalez F. J., and Peters J. M. (2012) Analysis of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) cistrome reveals novel co-regulatory role of ATF4. BMC Genomics 13, 665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yao P. L., Chen L. P., Dobrzański T. P., Phillips D. A., Zhu B., Kang B. H., Gonzalez F. J., and Peters J. M. (2015) Inhibition of testicular embryonal carcinoma cell tumorigenicity by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ- and retinoic acid receptor-dependent mechanisms. Oncotarget. 6, 36319–36337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Borland M. G., Krishnan P., Lee C., Albrecht P. P., Shan W., Bility M. T., Marcus C. B., Lin J. M., Amin S., Gonzalez F. J., Perdew G. H., and Peters J. M. (2014) Modulation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR)-dependent signaling by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ (PPARβ/δ) in keratinocytes. Carcinogenesis 35, 1602–1612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yao P. L., Morales J. L., Zhu B., Kang B. H., Gonzalez F. J., and Peters J. M. (2014) Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPAR-β/δ) inhibits human breast cancer cell line tumorigenicity. Mol. Cancer Ther. 13, 1008–1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nakajima T., Wang R. S., Elovaara E., Gonzalez F. J., Gelboin H. V., Vainio H., and Aoyama T. (1994) CYP2C11 and CYP2B1 are major cytochrome P450 forms involved in styrene oxidation in liver and lung microsomes from untreated rats, respectively. Biochem. Pharmacol. 48, 637–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Köhler G., and Milstein C. (1975) Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature 256, 495–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hansen B., Arteta B., and Smedsrød B. (2002) The physiological scavenger receptor function of hepatic sinusoidal endothelial and Kupffer cells is independent of scavenger receptor class A type I and II. Mol. Cell Biochem. 240, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yao P. L., Lin Y. C., and Richburg J. H. (2011) Transcriptional suppression of Sertoli cell Timp2 in rodents following mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate exposure is regulated by CEBPA and MYC. Biol. Reprod. 85, 1203–1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]