Abstract

A 58-year-old right-handed woman presented with neck pain and right hemibody decreased pain and temperature sensation. Over the next 3 days, she developed left ptosis and miosis. The Horner syndrome was confirmed with 0.5% apraclonidine and neuromyelitis optica immunoglobulin G antibody titres were positive. Magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical spine showed a longitudinally extensive intramedullary expansile lesion more prominent on the left, with post-contrast enhancement extending from C2 to C5, consistent with neuromyelitis optica. This patient was diagnosed with neuromyelitis optica with an associated left Horner syndrome.

Keywords: Horner syndrome, neuromyelitis optica, NMO IgG antibody

Case Report

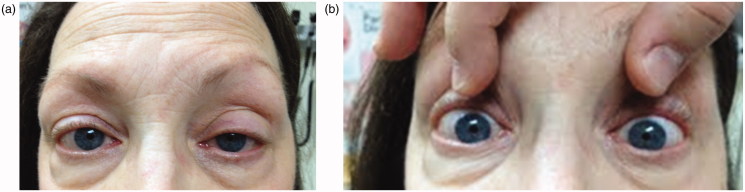

A 58-year-old right-handed woman presented with neck pain and associated right hemibody decreased pain and temperature sensation. Symptoms began a few days previously with severe neck pain after waking from an afternoon rest, then progressive loss of temperature sensation to cold on her right hand, followed by her right leg. She had also been experiencing a burning sensation over her shoulders and clavicles. Three days later she developed left ptosis and miosis (Figure 1a and b). Medical history was notable for Graves disease treated with radioactive iodine ablation. She also had a prior history of migraine headaches with aura and restless legs syndrome. Medications were laevothyroxine and pramipexole.

FIGURE 1.

(a) Left-sided ptosis. (b) Pupil asymmetry with left-sided miosis; left pupil measuring 2.5 mm, compared with right pupil measuring 4 mm.

On initial examination, she had hypalgesia and thermohypaesthesia on the right arm and leg, with impaired dexterity and brisk muscle stretch reflexes on the left hemibody. After 3 days, she also developed left ptosis and miosis. Pupils measured 4 mm in the right eye and 2.5 mm in the left eye in the dark, becoming isocoric at 1.5 mm in light. The diagnosis of Horner syndrome was confirmed with the application of 0.5% apraclonidine drops, which brought about reversal of the anisocoria and elimination of the ptosis.

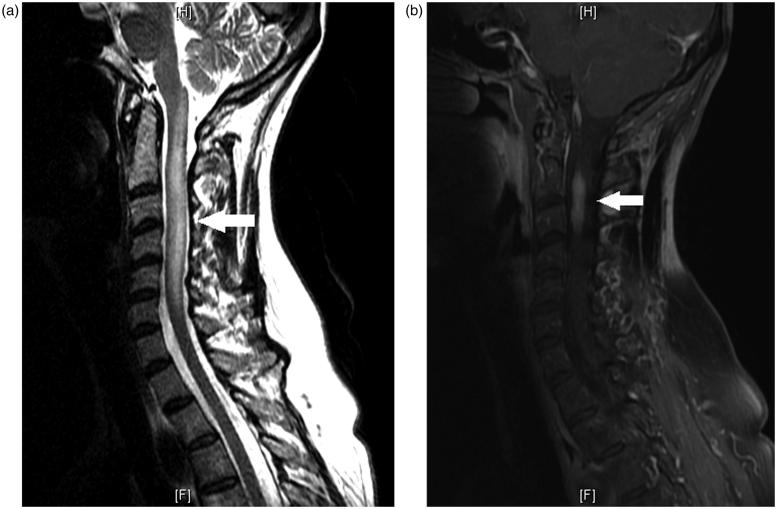

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical spine was remarkable for a longitudinally extensive intramedullary expansile lesion more prominent on the left, with post-contrast enhancement extending from C2 to C3 (Figure 2a and b). Extensive ancillary studies were performed, and neuromyelitis optica (NMO) immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody titres (antibody to aquaporin-4) were elevated at 31.6 U/mL (reference: <3) as well as an increased IgG synthesis rate in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and elevated anti-TPO (thyroid peroxidase) antibody at 25.7 IU/mL (reference: <9). CSF showed a lymphocytic pleocytosis with white blood cell count (WBC) 25/μL (reference: <8) of which 74% were lymphocytes, and elevated protein content at 84 mg/dL (reference: <45). Visual evoked potentials (VEPs) were abnormal with evidence of a mildly prolonged right P100 response. The remainder of ancillary studies were unremarkable.

FIGURE 2.

(a) Sagittal view of T2 image of MRI of the cervical spine showing a longitudinal lesion, extending from C1 through the inferior level of C6 with expansion of the cord. (b) Sagittal view of T1 post-contrast MRI of the cervical spine showing enhancement of the cervical cord predominantly at C2–C3.

She was treated with a 5-day course of 1000 mg intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone daily, and discharged on daily oral prednisone starting at 50 mg daily followed by a slow taper over 1 month. At the 1-month follow-up visit, MRI of the cervical spine showed decrease in size of previously noted longitudinally extensive transverse cervical myelitis on both T2/FLAIR (fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) as well as post-contrast images. Symptoms were improved. Azathioprine at 50 mg three times a day was started and she continued with oral prednisone at 10 mg daily. Rituximab was also infused twice. Following this treatment, she still exhibited a left-sided Horner syndrome, but her right hemibody numbness was markedly improved. MRI of the cervical spine also showed a decrease in T2/FLAIR hyperintensity in the left hemicord at the C2–C3 level.

Discussion

Horner syndrome is characterised by miosis, ptosis, and sometimes anhydrosis. It results from a lesion anywhere along the three-neuron oculosympathetic pathway that supplies the head, eye, and neck. The aetiology of Horner syndrome is dependent on the location of the lesion along the oculosympathetic pathway.1 In order to localise the origin, associated neurological signs and symptoms can be used. In the preceding case, the patient had an intramedullary lesion affecting nerve fibres from C2 through C5, indicating that she had a first-order neuron lesion leading to her Horner syndrome. In subtle cases of Horner syndrome, cocaine or apraclonidine drops can be used to confirm the diagnosis, although the latter is increasingly being used.2 Apraclonidine is a direct α-adrenergic receptor agonist, with both weak α-1 activity that mediates pupillary dilation, and strong α-2 activity that down-regulates norepinephrine release at the neuromuscular junction.3 The result is that with the administration of 1–2 drops of 0.5% apraclonidine, there is dilation of the miotic pupil due to denervation supersensitivity, and thus reversal of the anisocoria in patients with Horner syndrome such as was observed in this patient.4

NMO, or Devic disease, is an inflammatory condition of the central nervous system (CNS) characterised by both myelitis and optic neuritis. Both main clinical manifestations may present concurrently or with a time interval between symptoms.5 In the United States, NMO occurs most commonly among non-Caucasians, and it is more common in women with median age of onset of 40 years.6,7 NMO can be monophasic, although in 73–90% of cases it has been noted to have a relapsing course.8 The 5-year survival rate is 90% for patients with a monophasic course of disease and 68% for relapsing patients.6 The aetiology is not well defined, although elevated anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein–secreting cells in CSF have been observed and support a humoral inflammatory mechanism underlying NMO, likely B-cell dysfunction.9,10 Also, elevated glial fibrillary acidic protein in the CSF of affected patients suggests that astrocytes are the primary inflammatory target, particularly the astrocyte aquaporin-4 water channels (NMO IgG antibody).11,12

Diagnostic criteria for NMO were revised in 2006, and require that optic neuritis and acute myelitis be present along with two of three of the following supportive criteria: NMO IgG seropositivity, negative brain MRI at onset, and contiguous T2-weighted signal abnormality extending over at least three vertebral segments.13 In our patient, the prolongation in P100 response noted on VEPs was an indication that the patient had a clinically silent optic neuropathy.14 There has not been an association between NMO and Horner syndrome reported in the literature, although it is suspected that given the possible location of cervical cord lesions in NMO, Horner syndrome is likely to be observed.

Treatment for NMO has not been proven through controlled trials, although expert opinions for the acute phase recommend intravenous glucocorticoids (methylprednisolone 1000 mg/day for 5 or more days) followed by plasmapheresis in refractory or progressive symptoms. Long-term immunosuppression for at least 5 years is recommended in cases of established NMO, due to the high risk of relapse. Options for immunosuppresion include azathioprine (2.5–3 mg/kg/day) plus prednisone (∼1 mg/kg/day to be tapered), mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg twice a day plus prednisone as previously mentioned, mitoxantrone, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, or intravenous immune globulin (IVIG).15

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Note: Figure 1 of this article is available in colour online at www.informahealthcare.com/oph.

References

- 1.Kardon R. Anatomy and physiology of the autonomic nervous system. In: Miller NR, Newman NJ, Biousse V, Kerrison JB, editors. Walsh and Hoyt Clinical Neuro-ophthalmology. 6th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 2005;649–714 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown SM, Aouchiche R, Freedman KA. The utility of 0.5% apraclonidine in the diagnosis of Horner syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 2003;121:1201–1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morales J, Brown SM, Abdul-Rahim AS, Crosson CE. Ocular effects of apraclonidine in Horner syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 2000;118:951–954 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koc F, Kavuncu S, Kansu T, Acaroglu G, FIrat E. The sensitivity and specificity of 0.5% apraclonidine in the diagnosis of oculosympathetic paresis. Br J Ophthalmol 2005;89:1442–1444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Lucchinetti CF, Pittock SJ, Weinshenker BG. The spectrum of neuromyelitis optica. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:805–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wingerchuk DM, Hogancamp WF, O'Brien PC, Weinshenker BG. The clinical course of neuromyelitis optica (Devic’s syndrome). Neurology 1999;53:1107–1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Riordan JI, Gallagher HL, Thompson AJ, Howard RS, Kingsley DP, Thompson EJ, McDonald WI, Miller DH. Clinical, CSF, and MRI findings in Devic’s neuromyelitis optica. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996;60:382–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collongues N, Marignier R, Zéphir H, Papeix C, Blanc F, Ritleng C, Tchikviladzé M, Outteryck O, Vukusic S, Fleury M, Fontaine B, Brassat D, Clanet M, Milh M, Pelletier J, Audoin B, Ruet A, Lebrun-Frenay C, Thouvenot E, Camu W, Debouverie M, Créange A, Moreau T, Labauge P, Castelnovo G, Edan G, Le Page E, Defer G, Barroso B, Heinzlef O, Gout O, Rodriguez D, Wiertlewski S, Laplaud D, Borgel F, Tourniaire P, Grimaud J, Brochet B, Vermersch P, Confavreux C, de Seze J. Neuromyelitis optica in France: a multicenter study of 125 patients. Neurology 2010;74:736–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Correale J, Fiol M. Activation of humoral immunity and eosinophils in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2004;63:2363–2370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucchinetti CF, Mandler RN, McGavern D, Bruck W, Gleich G, Ransohoff RM, Trebst C, Weinshenker B, Wingerchuk D, Parisi JE, Lassmann H. A role for humoral mechanisms in the pathogenesis of Devic’s neuromyelitis optica. Brain 2002;125:1450–1461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takano R, Misu T, Takahashi T, Sato S, Fujihara K, Itoyama Y. Astrocytic damage is far more severe than demyelination in NMO: a clinical CSF biomarker study. Neurology 2010;75:208–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Popescu BF, Lennon VA, Parisi JE, Howe CL, Weigand SD, Cabrera-Gómez JA, Newell K, Mandler RN, Pittock SJ, Weinshenker BG, Lucchinetti CF. Neuromyelitis optica unique area postrema lesions: nausea, vomiting, and pathogenic implications. Neurology 2011;76:1229–1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, Weinshenker BG. Revised diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2006;66:1485–1489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groseth GS, Ashman EJ. Practice parameter: the usefulness of evoked potentials in identifying clinically silent lesions in patients with suspected multiple sclerosis (an evidence based review). Neurology 2000;54:1720–1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wingerchuk DM, Weinshenker BG. Neuromyelitis optica. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2008;10:55–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]