ABSTRACT

Sarcoidosis can affect the optic nerves by means of optic disc oedema secondary to posterior uveitis, optic disc oedema secondary to raised intracranial pressure, optic neuritis, optic atrophy secondary to compression or infiltration from a primary central nervous system lesion, and primary granuloma of the optic nerve head. The authors report the use of optical coherence tomography in assessing the response to immunosuppression in a 57-year-old woman with an optic nerve head granuloma.

KEYWORDS: Neurosarcoidosis, optic nerve, retinal oedema, optical coherence tomography, corticosteroids

Case

A 57-year-old woman presented with a 2-week history of floaters and intermittent blurred vision in both eyes that had become constant on the day of admission. She had a 16-year history of sarcoidosis. She initially presented with chest pain and was found to have hilar lymphadenopathy on a chest radiograph. The diagnosis was confirmed histologically on trans-bronchial biopsy. She had had an episode of vertigo 6 years after this and was found to have a positive antinuclear antibody at this time. She had been maintained since on hydroxychloroquine.

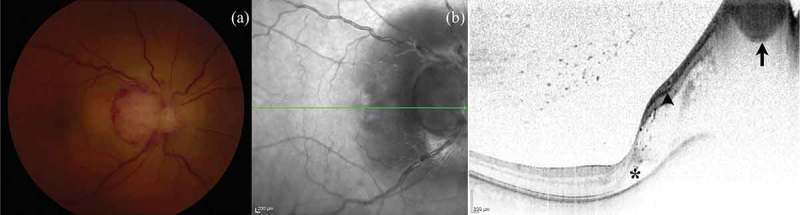

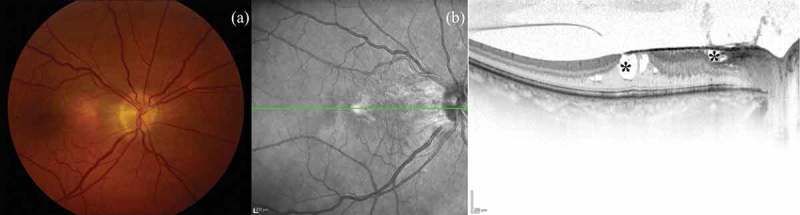

On examination, her visual acuity was 6/24 in her right eye and 6/18 in her left eye. She could only read the test plate of the Ishihara plates with each eye. She had an enlarged right blind spot. She had bilateral vitreous cells. She had a swollen left optic disc with haemorrhages. Her right optic disc was swollen and haemorrhagic, was infiltrated with an optic nerve head and peripapillary granuloma, and was surrounded by retinal thickening (Figure 1). Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) demonstrated the granuloma, but also intra-retinal oedema, pinpoint hyper-reflective dots suggestive of inflammatory cells, subretinal fluid, and vitreous cells. The neurological examination was otherwise normal.

Figure 1.

(a) Right fundus at presentation, demonstrating optic disc swelling and haemorrhage, an optic nerve head and peripapillary granuloma, and retinal thickening. (b) Spectral-domain OCT image confirming the presence of the granuloma (arrow), pinpoint hyper-reflective dots suggestive of inflammatory cells (arrowhead), retinal oedema, sub-retinal fluid (*), and vitreous cells.

Post-gadolinium magnetic resonance imaging revealed numerous small areas of enhancement within the parenchyma of both cerebral hemispheres, particularly in the region of the centrum semiovale, and subtle enhancement of the right optic nerve. At lumbar puncture she had an opening pressure of 25 cm of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The CSF contained 17 × 106/L white blood cells (100% lymphocytes), 0.53 g/L protein and 3.0 mmol/L glucose compared with a serum glucose of 4.2 mmol/L. There were no oligoclonal bands in either the CSF or serum. A chest radiograph was unremarkable.

A diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis was made with a right optic nerve head and peripapillary granuloma and left optic disc oedema. She was treated initially with 3 days of 1 g per day intravenous methylprednisolone, followed by a slowly reducing taper of oral prednisolone and the subsequent addition of weekly oral methotrexate.

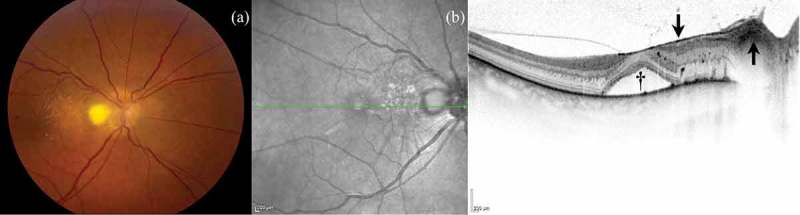

One month after presentation her visual acuity was 6/18 in each eye. She could still only see the test plate of the Ishihara plates with her right eye but could see 5/17 with her left eye. The right optic nerve head granuloma had shrunk considerably, with some resolution of the intra-retinal oedema and sub-retinal fluid, but a partial macular star had formed, as had an epiretinal membrane (Figure 2). There was only mild residual left optic disc swelling.

Figure 2.

(a) Right fundus 1 month after commencement of treatment, demonstrating resolution of the optic disc swelling, partial resolution of the granuloma and retinal thickening, but the development of a partial macular star. (b) Spectral-domain OCT image showing less prominence of the granuloma (upward arrow), but ongoing sub-retinal fluid (†) and an epiretinal membrane (downward arrow).

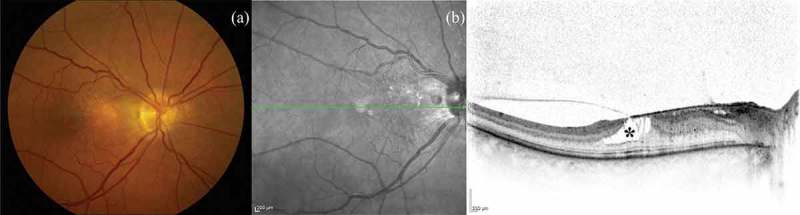

By 5 months, her visual acuity was 6/12+2 (7/17 of the Ishihara plates) in her right eye and 6/9 (8/17 of the Ishihara plates) in her left eye. The granuloma had virtually disappeared, and there had been resolution of the intra-retinal oedema and sub-retinal fluid, although she had developed optic disc pallor and presumed inner retinal atrophy (Figure 3). The left optic disc was now mildly atrophic.

Figure 3.

(a) Right fundus 5 months after commencement of treatment, demonstrating optic disc pallor and near complete resolution of the granuloma. (b) Spectral-domain OCT image showing resolution of the retinal thickening and sub-retinal fluid but the development of presumed inner retinal atrophy (*).

By 14 months her visual acuity was 6/9−2 (12/13 of the Ishihara plates) in her right eye and 6/9−1 (11/13 of the Ishihara plates) in her left eye. The granuloma had completely disappeared, although the inner retinal atrophy had become more pronounced (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

(a) Right fundus 14 months after commencement of treatment, demonstrating optic disc pallor and complete resolution of the granuloma. (b) Spectral-domain OCT image showing the development of more inner retinal atrophy (*).

Discussion

Sarcoidosis has a propensity to involve the eyes. Ocular involvement has been reported in 21–80% of cases1,2 with ocular manifestations including episcleritis, iris nodules, anterior uveitis, intermediate uveitis, panuveitis, cataract, vitreous opacities, epiretinal membrane, retinal vasculitis, branch retinal vein occlusions, and multifocal choroiditis.1,3 Neuro-ophthalmological sarcoidosis has been reported to cause cranial neuropathies, Horner’s syndrome, tonic pupil, and anterior and posterior optic pathway disease.4

Ingestad and Stigmar divided optic nerve involvement due to sarcoidosis into five categories: optic disc oedema secondary to posterior uveitis; optic disc oedema secondary to raised intracranial pressure; optic neuritis; optic atrophy secondary to compression or infiltration from a primary central nervous system lesion; and primary granuloma of the optic nerve head.5

In this case there was left optic neuritis and a right optic nerve head and peripapillary granuloma. The granuloma was associated with marked retinal oedema, a cellular retinal infiltrate, and sub-retinal fluid, visible on OCT. This proved to be steroid responsive, with resolution of the granuloma and retinal changes and improvement in vision but the development of inner retinal atrophy.

Previous cases reported in the literature in English of optic nerve head granuloma are listed in the Table 1.4–28 The reports were found by entering “optic nerve head granuloma” in MEDLINE and by review of the reference lists of the identified reports. Review of the 34 cases identified, including the present case, reveals that the mean age at presentation was 34 years (range: 11–59) with an equal gender mix of 17 males and 17 females. Of the 15 cases where racial origin was reported, there were 10 Black/African American cases (66.7%), 3 White Caucasian cases (20%), and 2 South Asian cases (13.3%). Twenty-seven cases (79.4%) were unilateral and 7 (20.6%) had bilateral optic nerve head granulomas at presentation. The optic nerve head granuloma was the first presentation of sarcoidosis in 23/34 of the cases (67.6%), although, when reported, 16/19 (84.2%) had extra-ocular manifestations of the disease. The presenting visual acuity was 20/20 or better in 11/41 (26.8%) affected eyes and 20/200 or worse in 11/41 (26.8%). There were additional ocular features of sarcoidosis in 37/41 (90.2%) of the affected eyes.

Table 1.

Previous case reports and case series of optic nerve head granuloma due to sarcoidosis.

| Study | Age in years, gender, and racial origin (where stated) | Unilateral or bilateral granulomas | Previous diagnosis of sarcoidosis | Initial visual acuity | Additional ocular features apart from the granuloma | Extra-ocular clinical features of sarcoidosis | Treatment | Length of follow-up | Final visual acuity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goldberg and Newell, 19446 | 24, male, African American | Unilateral | No | 20/50 | New vessels, subhyaloid, macular, and peripheral haemorrhages, and irregular constricted veins | Parotid gland enlargement, generalised and hilar lymphadenopathy | None | 5 months | 20/30 |

| Laval, 19527 | 48, female, White Caucasian | Unilateral | No | PL | Anterior chamber cells, posterior synechiae, distended retinal blood vessels, retinal haemorrhages, retinal nerve fibre layer oedema, and retinal nodules | None | None | None - enucleated on presentation | PL |

| Brunste, 19588 | 35, male | Bilateral | No | 6/6 OU | Pigmented precipitates on posterior corneal surfaces, white excrescences of the irises, and moderate venous congestion OU | Hilar lymphadenopathy | Corticotropin | 1 year | 6/18 OD, “normal” OS |

| Kojima, 19699 | 11, male | Unilateral | Yes | 0.06 | Macular star and venous thrombosis | Chest—type of involvement not stated | Oral steroids, and vitamins B1 and E | 1 year | 0.9 |

| Ingestadand Stigmar, 19705 | 26, male | Unilateral | No | 0.1 | Venous congestion, macular oedema and periarterial “yellow spots” with later haemorrhages, exudates, small vessel sheathing, and posterior vitreous detachment | Lung infiltrates and hilar lymphadenopathy, then later parotid swelling and diabetes insipid us | Prednisolone | 20 months | NPL |

| Laties and Scheie, 197010 | 25, female, African American | Unilateral | No | 6/6 | Small vessels on surface of granuloma, haemorrhages, and whitish deposits on retinal veins | Lung interstitial fibrosis and hilar lymphadenopathy | None | 8 months | 6/6 |

| 37, male, African American | Unilateral | Yes | “Blind” | None | Epilepsy and hilar lymphadenopathy | Steroids | 4 years | Not stated—patient died due to status epilepticus | |

| Jampol et al., 197211 | 29, female, African American | Bilateral | Yes | 20/20 OU | Peripapillary retinal folds, distended retinal veins OU and a single retinal haemorrhage OS | Left lung infiltrate, cervical and hilar lymphadenopathy | Prednisone | 3 months | Not stated |

| Kelley and Green, 197312 | 31, male, African American | Unilateral | Yes | PL | New vessels and peripapillary choroiditis, with later uveitis, synechiae, cataract, and glaucoma | Headaches, left lateral rectus palsy, enlarged parotid glands, left-sided neural deafness, cervical and hilar lymphadenopathy | Steroids | 15 years | NPL and enucleated |

| Turner et al., 197513 | 29, female, White Caucasian | Bilateral | Yes | 6/12 OD 6/9 OS | OD: Dilated capilaries, engorged retinal veins, candle-wax spots; cotton wool spots, haemorrhages, peripheral venous sheathing, and macular oedema OS: Dilated capillaries, engorged retinal veins, candle-wax spots, two small discrete retinal lesions, and nerve fibre bundle defects | Papular erythema of the legs, fever, polyarthralgia, facial palsy, knee effusions, hypercalciuria, and hilar lymphadenopathy | Prednisone then dexamethasone | 9 months | Not stated |

| Burns, 197614 | 22, female, African American | Unilateral | Yes | 20/200 | Localized exudative apparent retinal detachment and sub-retinal haemorrhages | Amenorrhoea, polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, skin nodules, supraclavicular and hilar lymphadenopathy | Prednisone | 4, months | 20/15 |

| Gass and Olson, 197615 | 41, male | Bilateral | Yes | 20/25 OD NPL OS | OD: Vitreous cells, retinal exudates and haemorrhages OS: Keratic precipitates, aqueous ray, posterior synechiae, and cataract | Epilepsy, ataxia, nystagmus, personality change, right-sided facial weakness, skin nodules, and an abnormal chest radiograph | Triamcinolone | 20 months | 20/80 OD NPL OS—patient died due to status epilepticus following an assault |

| Lustgarten et al., 198316 | 32, female, African American | Unilateral | No | 20/30 worsening to NPL | Initial swelling and papillophlebitis, then CRVO, increased granuloma size, and vitreous opacities | None | Prednisone | 13 months | NPL |

| Beardsley et al., 198417 | 23, male | Unilateral | No | 20/200 worsening to 20/400 | Vitreous opacities, peripapillary retinal detachment, perivenous exudates, and cotton-wool spots | Hypercalciuria and hilar lymphadenopathy | Prednisone | 9 months | 20/20 |

| 16, male | Unilateral | No | HM worsening to NPL | Vitreous opacities, peripapillary serous retinal detachment, and perivascular exudates, with later severe anterior uveitis and secondary glaucoma | Hilar lymphadenopathy | Periocular triamcinolone and prednisone | 9 months | NPL and enucleated | |

| 24, female | Unilateral | No | 20/20 | Flare and cells in the anterior chamber, exudates extending along the retinal blood vessels with overlying vitreous debris | Malar skin eruption | Prednisone and isoniazid | 18 months | 20/15 | |

| 33, male | Bilateral | No | 20/25 OU worsening to 20/40 OU | None | Hepatosplenomegaly, diffuse interstitial pulmonary markings, hilar and right paratracheal lymphadenopathy | Prednisone | 4 months | 20/40 OU | |

| Karma and Mustonen, 198518 | 42, female | Unilateral | Yes | 1.0 worsening to 0.1 | Initial nodular uveitis then iris granulomas, dilated leaking capillaries, nodes on the lower temporal vein and along scar margins of healed granulomas in the peripheral retina. Later vitreous opacification | Skin purple plaques, joint symptoms, liver dysfunction, and hilar lymphadenopathy | Prednisone | 3 years | 0.1 |

| 35, female | Unilateral | Yes | 1.0 worsening to CF | Initial lacrimal gland enlargement, corneal keratic precipitates, peripapillary iris atrophy, vitreous cells and snowball-like opacities, candle-wax exudates, and chorioretinitic lesions in the lower periphery. Later serous retinal detachment | Epilepsy, lupus pernio, submandibular gland enlargement, lung infiltration, and hilar lymphadenopathy | Prednisone | 2 years | CF | |

| Katz et al., 199119 | 56, female | Unilateral | No | 20/50 | Fullness of the peripapillary retina | Middle cranial fossa gadolinium-enhancing mass on MRI | Corticosteroids | Not stated | Not stated |

| Sivakumar and Chee, 199820 | 41, male, South Asian | Unilateral | No | 6/18 | RAPD, keratic precipitates, anterior chamber cells, flare, retrolental cells, vitritis, snowballs, and focal retinal vasculitis with perivascular sheathing | Hilar lymphadenopathy | IVMP followed by prednisolone | 2 years | 6/6 |

| Farr et al., 200021 | 31, female, African American | Unilateral | No | 20/25 worsening to 20/400 | Conjunctival nodules and haemorrhages peripheral to the granuloma | Hilar lymphadenopathy | Prednisone | 18 months | 20/25 |

| Asensio Sanchez et al., 200322 | 59, male | Unilateral | No | 0.6 | Macular folds | 67Gallium uptake in the lungs and lacrimal glands | Prednisone | 1 year | Not stated |

| Frohman et al., 200323 | 50, female | Unilateral | No | NPL | Periphlebitis and macular exudate | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| 30, female | Bilateral | No | 20/20 OU | Busacca nodules OU | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | |

| 32, female | Unilateral | No | 20/70 | Lacrimal gland enlargement, ptosis, uveitis, vitreous snowballs, and optic disc shunt vessels | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | |

| Ismail et al., 200524 | 40, male, Malay | Unilateral | No | 6/24 | Mild anterior chamber reaction, moderate vitritis with a few snowballs and vitreous strands, tortuous retinal vessels with sheathing of the superior branch of the retinal vein, and multiple yellow-white choroidal lesions in the peripheral retina | 67Gallium uptake in he right lacrimal gland with “Panda sign” | Topical dexamethasone and prednisolone | Not stated | 6/6 |

| Al-Jamal and Kivelä, 200825 | 27, male | Unilateral | No | 0.33 worsening to CF | Vitreous opacities and an exudative retinal detachment | Lung infiltrates and hilar lymphadenopathy | IVMP followed by prednisolone | 1 year | 0.1 |

| Jafferji and Biswas, 200826 | 49, female | Unilateral | No | 6/24 | Hard exudates, optic nerve head vascular tortuosity with haemorrhages, and pars plana exudates | None | IVMP followed by prednisolone and methotrexate | 24 months | 6/5 |

| Koczman et al., 20084 | 24, male, African American | Unilateral | No | 20/25 | Keratoconjunctivitis sicca and panuveitis | Testicular involvement and hilar lymphadenopathy | IV corticosteroids then prednisone and methotrexate | Not stated | 20/15 |

| Moschos and Guex-Crosier, 200827 | 19, male, Black | Bilateral | No | 1.0 OD 0.8 OS | OD: No other changes OS: Corneal keratic precipitates, iris nodule, optic disc leakage, and multifocal choroidal lesions | Hilar lymphadenopathy | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Goldberg et al., 201428 | 41, female | Unilateral | Yes | CF | Infiltrative lesion on the choroid with thickening of peripapillary retina and attenuation of the photoreceptor ellipsoid zone on OCT | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| 38, male | Unilateral | No | 20/50 | Vitritis and cotton wool spots with retinal oedema on OCT | Not stated | IVMP followed by prednisone | 6 weeks | 20/20 | |

| Present case | 57, female, White Caucasian | Unilateral | Yes | 6/24 | Vitreous cells, intra-retinal oedema, retinal inflammatory infiltrate, and sub-retinal fluid | Vertigo and hilar lymphadenopathy | IVMP followed by prednisolone and methotrexate | 14 months | 6/9−2 |

Note. CF = counting fingers; CRVO = central retinal vein occlusion; HM = perception of hand movements; IV = intravenous; IVMP = Intravenous methylprednisolone; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; NPL = no perception of light; OCT = optical coherence tomography; PL = perception of light; RAPD = relative afferent pupillary defect.

Histological examination of an involved optic nerve head from a case that required enucleation after the development of painful anterior uveitis and secondary glaucoma showed non-caseating granulomatous inflammation protruding forward through the scleral canal with an overlying retinal detachment.17 In a further case following enucleation the optic nerve head anterior to the lamina cribrosa was oedematous with a large nodule of epithelioid cells and lymphocytes adjacent to the outer nuclear layer of the retina. A further nodule was present in the centre of the optic cup. Near the optic nerve head the retinal vessels were markedly distended with numerous haemorrhages.7 In an autopsy case, the optic nerve head and surrounding retina were heavily infiltrated by a non-necrotising granulomatous reaction extending from the inner retinal layers and the surface of the optic disc into the vitreous. This was associated with lymphocytic and neutrophilic perivascular infiltration as well as non-caseating epithelioid cell nodules and giant cells. There was also prominent folding of the peripapillary retina.15

The type of treatment was reported in 29 of the cases. The vast majority (23/29, 79.3%) were treated with corticosteroids, with 3/29 (10.3%) receiving additional immunosuppression with methotrexate. Three older cases did not receive any treatment. Outcome visual acuity was recorded for 27/41 affected eyes, with 10/27 (37.0%) recovering to 20/20 or better, but 9/27 (33.3%) were 20/200 or worse at last follow-up. Poor recovery was associated primarily with additional ocular pathology such as uveitis,7,12,15,17,18 central retinal vein occlusion,16 and retinal detachment,18,25 with only one case of poor outcome directly due to the optic nerve head granuloma.5

There was been one other report of the use of OCT to investigate optic nerve head granuloma.28 In the two cases reported, the granulomas were associated with peripapillary retinal oedema, as in the present case, although one of these cases had choroidal inflammation as well. Follow-up OCT was carried out after 12 months in one case demonstrating normalisation of the peripapillary outer retinal layers and decreased optic nerve head height with the development of optic nerve head gliosis. OCT is therefore a useful tool for demonstrating the additional retinal pathology that is usually present with optic nerve head granulomas in sarcoidosis and for monitoring the response to treatment, since visual outcome in these cases seems principally related to the additional ocular features of sarcoidosis rather than direct effects of the optic nerve head granuloma itself.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- [1].Lee SY, Lee HG, Kim DS, Kim J-G, Chung H, Yoon YH.. Ocular sarcoidosis in a Korean population. Korean Med Sci 2009;24:413–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ohara K, Okubo A, Sasaki H, Kamata K.. Intraocular manifestations of systemic sarcoidosis. Jpn J Ophthalmol 1992;36:452–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Pefkianaki M, Androudi S, Praidou A, Sourlas V, Zakynthinos E, Brazitikos P, Gourgoulianis K, Daniil Z.. Ocular disease awareness and pattern of ocular manifestation in patients with biopsy-proven lung sarcoidosis. J Ophthal Inflamm Infect 2011;1:141–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Koczman JJ, Rouleau J, Kardon RH, Wall M, Lee AG.. Neuro-ophthalmic sarcoidosis: the University of Iowa experience. Semin Ophthalmol 2008;23:157–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ingestad R, Stigmar G.. Sarcoidosis with ocular and hypothalamic pituitary manifestations. Acta Ophthalmologica 1971;49:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Goldberg S, Newell FW.. Sarcoidosis with retinal involvement. Arch Ophthalmol 1944;32:93–96. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Laval J. Ocular sarcoidosis. Am J Ophthalmol 1952;35:551–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Brunste E. Ocular sarcoidosis: report of five cases with fundus changes. Dan Med Bull 1958;5:217–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kojima K. Fundus involvement in sarcoidosis. J Clin Ophthalmol 1969;23:790–793. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Laties AM, Scheie HG.. Sarcoid granulomas of the optic disk: evolution of multiple small tumors. Trans Am Ophth Soc 1970;68:219–233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jampol LM, Woodfen W, McLean EB.. Optic nerve sarcoidosis. Arch Ophthalmol 1972;87:355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kelley JS, Green WR.. Sarcoidosis involving the optic nerve head. Arch Ophthalmol 1973;89:486–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Turner RG, James DG, Friedmann AI, Vijendram M, Davies JPH.. Neuro-ophthalmic sarcoidosis. Br J Ophthalmol 1975;59:657–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Burns CL. Unusual ocular presentation of sarcoidosis. Ann Ophthalmol 1976;8:69–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gass JDM, Olson CL.. Sarcoidosis with optic nerve and retinal involvement. Arch Ophthalmol 1976;94:945–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lustgarten JS, Mindel JS, Yablonski ME, Friedman AH.. An unusual presentation of isolated optic nerve sarcoidosis. J Clin Neuro-Ophthalmol 1983;3:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Beardsley TL, Brown SV, Syndor CF, Grimson BS, Klintworth GK.. Eleven cases of sarcoidosis of the optic nerve. Am J Ophthalmol 1984;97:62–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Karma A, Mustonen EMA. Neuro-Ophthalmology 1985;5:231–246. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Katz B, Newman S, Wall M.. Disc edema, transient obscurations of vision, and a temporal fossa mass. Surv Ophthalmol 1991;36:133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sivakumar M, Chee SP.. A case series of ocular disease as the primary manifestation in sarcoidosis. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1998;27:560–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Farr AK, Jabs DA, Green WR.. Optic disc sarcoid granuloma. Arch Ophthalmol 2000;118:728–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Asensio Sánchez VM, Corral Azor A, Bartolomé Aragón A, De Paz García M. [Sarcoidosis of the optic nerve]. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol 2003;7816:165–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Frohman LP, Guirgis M, Turbin RE, Bielory L.. Sarcoidosis of the anterior visual pathway: 24 new cases. J Neuro-Ophthalmol 2003;23:190–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ismail S, Embong Z, Hitam WHW.. Gallium scan in diagnosing ocular sarcoidosis. Malay J Med Sci 2005;12:64–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Al-Jamal RT, Kivelä T.. Progressive visual loss and an optic disc tumour in a young man. Acta Ophthalmol 2008;86:341–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Jafferji SS, Biswas J.. Optic nerve head sarcoid granuloma treated with intravenous methyl prednisolone. Oman J Ophthalmol 2008;1:28–31. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Moschos MM, Guex-Crosier Y.. Anterior segment granuloma and optic nerve involvement as the presenting signs of systemic sarcoidosis. Clin Ophthalmol 2008;2:951–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Goldberg NR, Jabs DA, Busingye J.. Optical Coherence Tomography Imaging of Presumed Sarcoid Retinal and Optic Nerve Nodules. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2015; Aug 24. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2014.971972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]